3 minute read

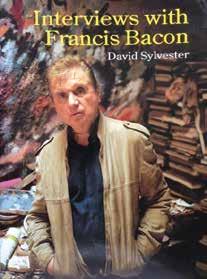

DAVID SYLVESTER’s Interviews with Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon’s frank and physical analysis of his working method when painting offers Marcel Theroux relief from feelings of despondency about his own writing.

Over the past 20 years, I’ve accumulated a small library of books that are intended to guide and inspire the would-be writer of fiction. Some propose to explain the universal principles of story with maths and diagrams (Georges Polti’s The Thirty- Six Dramatic Situations of 1916, Vladimir Propp’s Morphology of the Folktale of 1928 or Christopher Booker’s The Seven Basic Plots of 2004); some bark advice like a sergeant-major urging conscripts round an obstacle course; others offer the flailing writer the literary equivalent of a bosomy cuddle. And I think I’ve taken something from most of them, even the ones I eventually consigned to the charity shop. But the book that I’m most likely to turn to when in a deep gloom about my own work is not a book about writing at all.

Interviews with Francis Bacon was first published under the title The Brutality of Fact in 1987. It’s a collection of interviews that the art critic David Sylvester conducted with Bacon over a period of 25 years and is especially good for dipping into when your own work has ground to a halt.

Sylvester questions Bacon in minute detail about his method of working. Bacon’s answers speak to anyone who’s tried to make a sincere work of art in any medium. He is funny, and bracingly frank. Bacon paints when he’s drunk, he paints when’s he bored, and he paints with terrible hangovers. Sometimes he feels incapable of painting figures, so he paints landscapes instead. Often he flings paint haphazardly at the canvas in the hope that it will spark an idea. And his best work, he says, seems to come when he’s teetering on the edge of total despair.

His appetite for work borders on obsession. The paintings are the product of a lifetime’s passion for visual images, for looking at other art, and manipulating paint on canvas. ‘You see, I have looked at everything in art, ’ Bacon says at one point, and it doesn’t sound like a boast.

Alongside Bacon’s connoisseurship and hard work, there is something else: a recurring preoccupation with the importance of chance and instinct. ‘I can quite easily sit down and make what is called a literal portrait of you, ’ Bacon tells Sylvester, but that’s not what interests him. He’s driven to find ways to make images that feel fresher and more immediate, to create art which seems ‘to come straight out of what we call the unconscious with the foam of the unconscious locked around it – which is its freshness’ . The two men return to this subject again and again, and it’s some of the most thought-provoking material in the book. These sentences, like Bacon’s paintings, imply much more than they tell. They’re pregnant and suggestive, quite unlike the specious formulations of most creativewriting textbooks. ‘The hinges of form come about by chance seem more natural and to work more inevitably, ’ Bacon explains. It’s a throwaway remark, but it contains a deep idea about not relying on mere intelligence, or intelligence alone; to have faith that darker, stranger avenues will lead you to ‘a vividness that no accepted way of doing it would have brought about’ .

Most importantly of all, the book administers first aid to the zone that is most likely to be afflicted in a blocked writer: that is, the inner conviction that there’s any point in making art at all. Bacon doesn’t elaborate his theories about art in a systematic way, but the same phrases recur across the interviews. He talks about the power of art to ‘thicken life’ , to ‘unlock the valves of feeling’ , and bring things ‘onto your nervous system more strongly’ . It’s a less portentous and more convincing version of Kafka’s idea that art is an axe to smash the frozen sea inside us.

I’ve read the book many times, and not once have I closed it without feeling revitalised.