PROSE POETRY ART INTERVIEWS with featured work about NATURE & CLIMATE

2023

2023 Lowell, Massachusetts editors Richard P. Howe, Jr. Paul Marion

Copyright © 2023

by The Lowell Review

No content may be reproduced without permission from The Lowell Review and the individual authors except for brief quotations in critical articles and media reports. Contributors retain rights to their work following publication.

Published in the United States of America

All rights reserved

The Lowell Review is an annual publication with content from the RichardHowe.com blog, as well as submitted and curated material. To view this issue and back issues online, visit TheLowellReview.com

Bound copies of all issues are available at Lulu.com ($15 USD plus shipping cost).

Please send correspondence and work for consideration (June through October) to TheLowellReview@gmail.com

Work previously published in the RichardHowe.com blog is reprinted by permission of the authors.

Thanks to Shawn Levy, Sanary Phen, David Getty for Sarah Getty, Michael Casey, Ivy Ngugi, Gary Lawless, Alfred Nicol, Resi Ibañez, Brian Herzog, and Jay Atkinson for permission to reprint their previously published work. See the Contributors section for details on permissions.

Thanks to David Brow for permission to reprint his photographs. Special thanks to penguinrandomhouse.com for an advance copy of The Climate Book by Greta Thunberg.

The works of fiction are inventions of the authors.

editors

Richard P. Howe, Jr.

Paul Marion

contributing editors

David Daniel

John Wooding

art direction & design

Joey Marion

cover art

© Nancy Wells Woods

“Coleus” (watercolor sketch)

The Lowell Review 2023

The Lowell Review

The Lowell Review 2023

The Lowell Review brings together writers and readers in the Merrimack River watershed of eastern New England with people everywhere who share their curiosity about and passion for the small and large matters of life. Each issue includes essays, poems, stories, criticism, opinion, and visual art.

In the spirit of The Dial magazine of Massachusetts, edited by Margaret Fuller and Ralph Waldo Emerson in the 1840s, The Lowell Review offers a space for creative and intellectual expression. The Dial sought to provide evidence of “what state of life and growth is now arrived and arriving.”

This publication springs from the RichardHowe.com blog, known for its “Voices from Lowell and beyond.” In America, the name Lowell stands out, associated with industrial innovation, working people, cultural pluralism, and some of the country’s literary greats.

The Lowell Review 2023

Mission

The Lowell Review 2023

The Lowell Review 2023 Contents ONE John Wooding • There’s Something Happening Here . . ......................................................... 1 Jennifer Myers • Rollie’s Farm ............................................................................................33 Carla Panciera • Owl Winter 10 Emilie-Noelle Provost • Eulogy for a Sugar Maple ............................................................. 14 Environmental Youth Task Force: Smithsonian Institution Trip 16 Babz Clough • Tomorrow There Will Be More of Us: An interview with Brad Buitenhuys of the Lowell Litter Krewe (Spring 2022) ......................... 19 Book Review • The Climate Book: The Facts and the Solutions 23 Robert Frost • A Brook in the City ...................................................................................... 25 Amy Lowell • The Pike 26 Gary Lawless • Stork sky amber river .................................................................................. 27 Cheryl Merz • Steinbeck and Ricketts on the Coast of Rhode Island ......................................28 Dawn Paul • Chance 29 Sanary Phen • Nature’s Oasis ............................................................................................ 30 John Wooding • No More Silent Springs ............................................................................. 31 Juliette N. Rooney-Varga • UMass Lowell Climate Change Initiative 36 Ingrid Hess • Go Green with UCC! ......................................................................................39 Ruairi O’Mahony • A Sustainable Campus 41 David Kriebel and the Staff of the Lowell Center for Sustainable Production • Building a Cancer-Free Economy ......................................... 45 Gary Metras • History of the Button Factory 50 Chath pierSath • Climate Signs .......................................................................................... 51 Mary Bonina • Googins Rocks 52 Ed Meek • Anthropocene ....................................................................................................53 Amanda Leahy • Fragment 06/28/20 ................................................................................ 54 Resi Ibañez • The Language of Birches 55 Ellsworth Scott • Los Angeles Evening ...............................................................................56

The Lowell Review 2023 TWO Tom Sexton • Man on a Cloisonné Vase .............................................................................59 Julien Vocance • from One Hundred Visions of War 60 Bill O’Connell • Two Poems: War in Ukraine ......................................................................63 Gary Metras • April 6, 2022 ...............................................................................................65 Jonathan Blake • After the War: Letter to O’Connell 66 THREE Shawn Levy • from A Year in the Life of Death .................................................................... 69 Claire Keyes • My Symphony Sid 71 Javy Awan • Isthmus .......................................................................................................... 72 Ricky Orng • IKEA ............................................................................................................ 73 Nancy Jasper • Grand Alap: A Window in the Sky 75 Sarah Getty • Spring Cleaning ............................................................................................ 76 FOUR Juan Delgado • Finches in the ICU: Incisionettes 81 FIVE Anthony “Tony” Accardi • August 18, 1966: The Beatles at Suffolk Downs . . . and Me, Too ............. 89 Charlie Gargiulo • The Beatles Land in Little Canada 91 Susan April • “It Needs Sweeping”......................................................................................95 Mike McCormick • A Catholic Schoolboy Discovers The Beatles 98 John Wooding • “Love Me Do” ......................................................................................... 101 Louise Peloquin • “Little Child, Won’t You Dance with Me?”............................................. 102 Gregory F. Delaurier • Le Hibou 105 SIX Marie Frank • Lowell’s Mid-Century Modern Architecture: Eugene Weisberg ..................... 109 David Daniel • Please Hold for Mr. Marek 110

The Lowell Review 2023 Contents Joe Blair • “Watch Our Show?” ......................................................................................... 113 Áine Greaney • Unnatural 115 Juliet H. Mofford • Susannah North Martin: “A Martyr of Superstition” ........................... 122 SEVEN John Greenleaf Whittier • The Kansas Emigrants 129 Tom Sexton • Medicine Hat, Alberta ................................................................................130 Cornelia Veenendaal • Paul Muldoon Day in Lawrence 131 Bunkong Tuon • I Give to You What I Did Not Have .......................................................... 132 Steven Riel • from Précieux-Sang ..................................................................................... 133 Ivy Ngugi • Two Poems from All the Peaches & Mangoes I Would Sell for You 134 Michael Casey • Two Poems ............................................................................................ 136 EIGHT Bob Hodge • Coffee Shop Musings #8 141 Jerry Bisantz • Ain’t Got Nuthin’ (Writer’s Cramp Covid) ................................................... 143 Jason O’Toole • Submarine Girl ........................................................................................ 145 Thomas Wylie • Cold Car 146 Rodger Legrand • Zero..................................................................................................... 147 Jacquelyn Malone • Dusk in the City 148 Judith Dickerman-Nelson • Proofs .................................................................................. 149 NINE Chaz Scoggins • Baseball Revival, October 1975 153 J. D. Scrimgeour • Racist .................................................................................................. 157 Jack Neary • The Old(ish) Ballgame .................................................................................. 168 Fred Woods • Fishing with Walter 171 TEN: JACK KEROUAC CENTENNIAL ( II ) Jay Atkinson • Requiem for Jack Kerouac .......................................................................... 175 David Brow (Photographs) • Jack Kerouac’s Funeral (1969) 180

The Lowell Review 2023 Roger West • Never Forget You Are a Breton: Jack Kerouac Centenary ............................... 187 Susan K. Gaylord • Kerouac in Lowell: Early Events 189 Brian Herzog • Censorship and Resistance ........................................................................ 192 Gabriella Martins • Damaged Goods 194 James Provencher • The Valley of the World...................................................................... 196 David Cappella • Ti Jean .................................................................................................. 197 Rev. Steve Edington • The Americas of Jack Kerouac and John Steinbeck 198 Contributors ................................................................................................................... 199

SECTION I

“Many communities on the frontlines of the climate crisis are already experiencing loss and damage. Communities cannot adapt to extinction; communities cannot adapt to starvation. The climate crisis is pushing so many people in places where they cannot adapt anymore. . . . If you traveled two to three hours away from Kampala to a certain rural community, you’ll understand how people would struggle to find water and how people’s crops are drying up because of the extreme dry conditions. . . . In the end, we cannot eat coal, we cannot drink oil.”

—Vanessa Nakate, Uganda, Climate activist, Sustainable Development Goals, un.org, 1/22

“Adults keep saying we owe it to the young people, to give them hope, but I don’t want your hope. I don’t want you to be hopeful. I want you to panic. I want you to feel the fear I feel every day. I want you to act. I want you to act as you would in a crisis. I want you to act as if the house is on fire, because it is.”

—Greta Thunberg, Sweden, Climate activist, World Economic Forum, theguardian.com, 1/19

“This fight for climate justice doesn’t extend to our physical environment alone but also impacts negatively on our children’s and our young persons’ mental health environment. . . . We truly believe that there must be far greater support by the international community to us within Small Island Developing States and helping us to become more climate resilient and adapt better to the impact that the climate crisis is having on our lives today.”

—Ashley Lashley, Barbados, leader, HEY (Health and Environment-friendly Youth) Campaign, with young people across the Caribbean, un.org, 4/22

“. . . I talk about the climate movement because that’s anti-chaos. That’s a knitting-together of people. I went to a conference the other day in Barcelona, and there were, I don’t know, five hundred people. There are twenty whom I’ll probably have further conversations with. I thought, How many conferences of that scale were going on that weekend? If everybody in those conferences was making roughly the same number of connections—I get this picture of this movement becoming powerful. It’s not the David and Goliath situation we’d thought, because, actually, we’re Goliath.”

—Brian Eno, England, musician and activist, The New York Times Magazine, 11/22

The Lowell Review 2023

The Lowell Review 2023

“Whatever economic competitiveness, whatever set of family values, whatever sense of societal inclusiveness we achieve will be torn apart if we must fight over access to water, food, energy, and clean air.”

—Paul E. Tsongas of Lowell, Mass. (1941-1997), from Journey of Purpose, 1995

Concord River, Lowell, photo by Joey Marion

There’s Something Happening Here . . .

john wooding

We can only hope that there is no longer a need to highlight the enormous challenges and dangers to all of us and our world resulting from global warming and climate change. It is by now obvious that we face potentially devastating consequences of decades of inaction. Since industrialization in nations of the north, especially, the temperature of the Earth increased 1.2° Celsius, stressing the planet’s ice zones, rainforests, permafrost, and seas. The tipping point is not far off, conditions that can radically change life around the globe: severe droughts, brutal storm systems, and rising ocean levels. The 2015 Paris Agreement signed by 195 countries seeks to keep global warming under 1.5° Celsius and no more than 2° Celsius in relation to the pre-industrial age.

There are ways we can mitigate the worst impacts. As the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change pointed out in its April 2022 report, we can work together to help prevent a catastrophe. The ways are well-known: get off the addiction to fossil fuel and switch to renewable energy sources, make cities Green, decarbonize the world’s buildings, switch to electric vehicles, commit to fairness and equity, teach well and often about how we can work to stop further damage. This can seem beyond our individual efforts, the challenges too big and far away.

It is often said that all politics is local. Much the same can be said of the fight against global warming. The more towns and cities, neighborhoods, and communities collaborate in as many ways as possible, the greater the chance that we can survive a warming world and save it for our children and our children’s children. Some of that local work is going on here in Lowell.

In the following pages, we offer several things that people are doing in the community and at UMass Lowell (UML) and Middlesex Community College. People working together to find solutions and to mobilize and educate. Interspersed are essays and poems that give us ways to look at and appreciate Nature and the daily planet.

The Lowell Parks & Conservation Trust teamed up with Mass Audubon and Mill City Grows to conserve the land and beauty of Rollie’s Farm. As Jen Myers points out, these organizations foresee a multitude of uses for the land such as restoration of the Christmas tree farm; maintaining the land as a working farm that includes a food forest and community gardens; and building a nature center for educational programming. Knowledge, green space, a place to breathe, less than a mile from downtown Lowell.

Caring for Earth shows up in many forms. The Lowell Litter Krewe beautifies public

The Lowell Review 1 2023 Section I

spaces, putting in 1,426 hours and picking up 48,600 pounds of trash before 2022 was over. Six hundred unique volunteers. High school and community college students of the Environmental Youth Task Force presented their display about protecting watersheds at a Smithsonian Institution festival in Washington, D. C.

Writers from the region and beyond reflect on Nature’s power and subtle grace seen in a sugar maple, a barred owl, a brook, and a pike. We have work by legacy authors Robert Frost, with roots along the Merrimack River, and Amy Lowell of Boston, related to the Lowells whose name is on the historic city and this publication.

A group of forty or so Lowell non-profits keeps the celebration of Earth Day front and center on the streets, and in folks’ hearts and minds. The UMass Lowell’s Climate Change Initiative is led by Juliette Rooney-Varga, who, with faculty colleagues and students, works tirelessly to investigate climate-friendly technologies and promotes science-based knowledge about a warming globe.

Ruairi O’Mahony is executive director of UML’s Rist Institute for Sustainability and Energy. At the Institute the team he leads transformed the campus, creating a deep commitment to shrinking the university’s carbon footprint and engaging with the Lowell community to advocate and develop a whole range of sustainable practices.

Children in Lowell schools are getting educated about climate change. UML students study climate change science and the social and political impacts of climate change. Faculty like Ingrid Hess use art and game-playing to increase awareness amongst the very young. We must teach the children well, and Ingrid is doing that.

Longtime UML faculty member David Kriebel and the Lowell Center for Sustainable Production, have, for nearly three decades, promoted the idea that to reduce toxic exposures to humans and damage to the environment we must reduce and eliminate unhealthful and dangerous chemicals and practices at the point of production. Many of those chemicals cause cancer, and the Center has been at the forefront of pushing for a cancer-free economy. That would be good.

In these pages there could be more examples of local people working to lessen global warming and its terrifying consequences. As the United Nations report argues, there are actions we can take, and we are doing so in part: using new technologies for renewable energy, finding new ways to sequester carbon, applying smart ideas about transportation, promoting locally grown organic food. But these will be ineffective unless we consider all aspects of equity and justice, as the poor here and everywhere disproportionately suffer the consequences of our rapidly warming planet. What we do here in Lowell matters. That we do it working together is the only way to succeed. There’s something happening here, and these examples make that exactly clear.

2 The Lowell Review 2023

Rollie’s Farm

jennifer myers

Something or someone was feasting on Rollie Perron’s coveted corn crop under the cloak of darkness.

This time it wasn’t the usual furry masked suspects; the Concord grape jelly in the humane traps that lured the raccoons in the past remained undisturbed.

Rollie scratched his head and looked around the remains of the matted corn rows at the edge of his field. He spotted a clue. A footprint. These were not raccoons trespassing on his land, the prints looked more like those left by some sort of dog.

Rollie had tussled with dozens of critters in his decades working the farm and knew there was only one way to crack this case—catch the culprits in the act, on their own timeline.

So, he hopped out of bed at 3 a.m. and headed out to the field with his giant flashlight. He shone the light up onto the hill at the back of the property that houses his sought-after Christmas trees. It immediately bounced back at him, reflected in the glowing eyes of a pack of coyotes preparing to descend into the corn field. He waved his arms and made some noise, successfully scaring the “cornivores” away.

“Now I knew I had a real creature to deal with,” he recalled.

He headed back out night after night playing watchman, patrolling the field from 3 a.m. to sunrise to keep the scavengers at bay. He paced. He perched himself atop the Christmas tree trimming ladder. After a few of these sleepless nights, he pitched his bright yellow tent at the edge of the field and slept there for three weeks. No sign of the coyotes.

The night he went back into the house to sleep, they returned. They must have smelled him when he was out here, he deduced.

“It’s such a battle. You’re fighting nature,” he said. “A farmer is fighting all the critters that want to eat your corn, want to eat your tomatoes you’re fighting woodchucks, you’re fighting racoons, you’re fighting birds. Then you are fighting weather—too much rain, not enough rain, wind, early frost.”

Now seventy-years-old and having worked the Pawtucketville land since his parents bought it in 1953, Rollie is ready to retire.

“Every season is like a marathon for me; it is go, go, go, go,” he said. “It is time to let go.”

But this is not an ending. It is more of a passing of the torch than the end of an era.

The twenty-two-acre Rollie’s Farm on Varnum Avenue, the last family farm in Lowell, will be conserved in perpetuity through a partnership formed by the Lowell Parks and Conservation Trust, Mass Audubon, and Mill City Grows.

The coalition will pay $3.85 million for the land; $1.5 million of which has been granted to the group by the Lowell Community Preservation Committee. The land, split into two

The Lowell Review 3 2023 Section I

parcels, 10 acres of which are owned by Rollie’s siblings, and the remainder by him, will be sold in two phases. The transaction will be complete in April 2024, following which Rollie will be given one year to remain living in the farmhouse before it is officially turned over.

The organizations foresee a multitude of uses for the land including restoration of the Christmas tree farm; maintaining the land as a working farm with a food forest and community gardens; and building a nature center for educational programming, as well as providing walking trails and a connection to the adjacent 1,100-acre Lowell-DracutTyngsboro State Forest.

Jane Calvin, Executive Director of the Lowell Parks and Conservation Trust said the full realization of the project will be phased in over several years and cost $6 to $10 million to do everything the three organizations want to do. They are working off of their own plans, while also incorporating ideas for use of the land collected in community listening and brainstorming sessions.

“The Rollie’s Farm project provides an incredible opportunity to demonstrate the value of working with the community to bring nature to the children and adults of Lowell,” said Renata Pomponi, Mass Audubon Senior Regional Director for Metro Boston. “Mass Audubon is proud to partner with Lowell Parks and Conservation Trust and Mill City Grows to provide an incredible new community resource built on the concepts of sustainable agriculture, ecological stewardship, and access to the outdoors.”

According to Pomponi, Lowell ranks 304 out of the state’s 351 cities and towns in percentage of protected open space, which is not surprising given the dense urban landscape found in most of the city. Preserving a swath of land as large as Rollie’s Farm, particularly in a city, is very rare, but essential for helping to offset the impact of climate change.

Pomponi said the planned ecological restoration of the Christmas tree farm, will significantly expand the tree canopy and the amount of greenhouse gases absorbed. Preserving the land, rather than building upon it and replacing grass with pavement, helps to reduce stormwater runoff into the neighborhood, lessening the impacts of severe weather events.

The farm acts as a carbon sink, meaning it absorbs more carbon than it releases into the atmosphere, which helps to counteract the effects of climate change.

Calvin said by expanding upon and restoring the existing green space, the land can have an even larger positive ecological impact.

“Both restoration of the farm’s ecology and Mill City Grows’ regenerative farming practices will enhance carbon sequestration,” she said. “Reducing tillage, eliminating chemicals, growing diverse cover crops, and adding compost all create a living soil that sequesters more carbon. This creates a positive feedback loop that will contribute to mitigating climate change and rebalancing the earth’s carbon cycle.”

Jessica Wilson, Executive Director of Mill City Grows said raising crops is key combatting the effects of climate change.

“I study and understand the effects of our global food system on the environment, so I really believe more local food is one of the many solutions we need to pursue to halt climate change,” she said. “The more time we spend actively engaging on the land, the better we can understand it and work in partnership with, rather than against, the best interests of the planet and each other.”

4 The Lowell Review 2023

The Lowell Review 5 2023

Section I

Photo by Paul H. Richardson

Additionally, protecting the land provides a place in the city where people can truly connect with nature through wildlife observation, summer camps, field research opportunities for students, as well as a variety of programs for people of all ages.

You do not have to leave the city to visit the country.

That is a lesson Rollie learned as a young boy. His parents, Roland, Sr. and Carole, bought the farm from the Palm family in 1953. Originally from Lawrence, Roland, Sr. met Carole when he was stationed in South Dakota while serving in the U.S. Air Force. She was the daughter of a cattle rancher. After Rollie was born, they decided to move back east, the 1952 Ford 8N tractor Roland Sr. bought from his father-in-law in tow.

Roland and Carole grew strawberries and pansies at what was then known as Carole’s Farm. She arranged beautiful baskets of flowers to sell at the farm stand. The family, which included Rollie and his siblings Mary Alice, Kathy, and Chris, had a milk cow, a steer they raised for beef named Bucky, and a horse named Ladybug.

The family farm was never a big money maker. Carole used her woody station wagon as a mini school bus, shuttling the kids who lived on Varnum Ave. to school to make extra money before she decided to go back to school herself and become a teacher. Roland Sr. worked for Raytheon. Although they both had full-time demanding jobs, they would come home and get right to work tending to the farm.

“I was dad’s little helper,” Rollie recalled.

He attended the Lexington Avenue School in Pawtucketville from grades 1-4. Before heading to school each morning, it was Rollie’s job to milk the cow, clean her stall, and feed her.

“I went to school smelling like a cow farm,” Rollie said. “I remember all of the kids making fun of me. It was so embarrassing.”

The Palm family, who had sold the Varnum Avenue farmland to the Perrons, still had a chicken farm up the street at the corner of Varnum Ave. and Trotting Park Rd. on the property that now houses the First Church or the Nazarene. Rollie recalls going with his dad to help Mr. Palm vaccinate the chickens cooped there.

“We would grab them by the legs, pull a wing out and stick them with two big needles, then toss them out the door of the coop and grab another one,” he said. “There were so many chickens there—thousands of them.”

But, growing up on a farm did have some advantages—in 8th grade Rollie rode Ladybug across the neighborhood to Maureen Manchenton’s house on Fourth Ave. for their first date. That was certainly not an experience other Lowell boys could offer.

And when he was a teenager and wanted to buy his first drum set, Rollie’s dad made a deal with him, giving him a patch of land on which to grow strawberries to sell. He could keep the profits.

Rollie spent that spring and early summer tending to his strawberry patch and then pedaling pints of the sweet ripe fruit to variety stores in the area to sell. As soon as he cleared $500, he bought his first Gretsch drum set and turned the strawberry patch back over to his dad.

In the early 1970s, times were bleak on Carole’s Farm. The thirty-eight acres was being taxed at the residential rate, leaving the Perrons scrambling to pay a $12,000 (equal to $85,000 today) annual property tax bill to the city.

In 1973, Massachusetts passed a new law—Chapter 61A which provides a tax break for

6 The Lowell Review 2023

actively farmed land, valuing the land as agricultural rather than residential, therefore cutting the tax burden significantly. The Perrons were thrilled—until they weren’t.

“The City Assessor refused to recognize our farm as a working farm,” Rollie said.

In the 2010 documentary The Last Farm in Lowell, written and directed by Andrew Szava-Kovats, Roland Sr. details the four-year legal battle with the city in which the family ultimately prevailed.

“They (city officials) didn’t want a farm in Lowell,” he said.

Although the open rural landscape of the Perron land in outer Pawtucketville is the absolute opposite of the dense industrial landscape of the city’s downtown, the fates of the two have run parallel in some ways.

In the late 1960’s Urban Renewal was all the rage. In Lowell that meant demolishing entire neighborhoods like the Little Canada enclave, home to many French-Canadian families, and the Hale/Howard neighborhood that was home to many of the city’s Jewish and African American families, in the name of “progress.” Boarding houses along the Merrimack Canal at Lucy Larcom Park were demolished. It was a time of tear down the old and build new. There was even talk of paving over the historic downtown area and building a shopping mall.

In the 1970’s that changed, as visionaries like Patrick Mogan, Sen. Paul Tsongas, and others put the focus on historic preservation and seeing Lowell’s unique past as a bridge to the future rather than as a detriment. The Lowell National Historical Park was born, and the remaining old mill buildings were repurposed for housing and commercial use.

In 1973, City officials likely did not want a farm in Lowell because they would rather

The Lowell Review 7 2023

Rollie Perron, photo by Jennifer Myers

Section I

see those acres turned into a housing development generating property tax dollars. That way of thinking has also evolved in recent years, as communities across the country fight to preserve open space for ecological and quality of life reasons. People have also realized the benefit and importance of locally grown fruits and vegetables.

Rollie, the only one of the Perron kids to show an interest in farming, became serious about it after returning to Lowell in 1974 following a stint in the U.S. Army. He attended Essex County Agricultural School (Essex Aggie) for a year but did not feel he was really learning anything. He dropped out.

A couple of his friends in the neighborhood told him about a really “cool” chemist working at the City’s water treatment plant named Charlie Panagiotakos.

“He was a really hip guy and all the young guys in the neighborhood would go down to hang out with him and see what he was doing,” Rollie said.

Rollie used his G.I. Bill benefits to attend night classes in water and wastewater treatment at the then-University of Lowell, where Panagiotakos taught. He eventually got a job working for the city’s water department as a plant operator.

At the same time, he was taking over the operations of the farm from his parents. Carole’s Farm became Rollie’s Farm.

A perfectionist and tinkerer by nature, he began experimenting with techniques for growing the best tomatoes and corn around. He increased his production by leasing nearby fields in Pawtucketville and in Hudson, N.H.

Rollie wracked his brain trying to figure out what to do with the sandy-soiled twelveacres on the back of the property. Then he remembered that his dad once planted some Christmas trees up there, but they were not properly cared for and never amounted to much.

“That always stuck in my head,” he said.

In 1975, he began clearing the land and planted a couple of hundred Norway Spruce trees. They take eight to nine years to mature to proper Norman Rockwell-worthy Christmas trees. Over the years he has meticulously hand-fertilized, trimmed, and sprayed the Christmas tree forest and expanded the number and variety of trees available—Balsam, Corkbark, Concolor, and Korean firs.

For the last four decades, families have been taking an annual tractor ride back in time, making their way up into the grove at Rollie’s Farm to pick out the perfect holiday tree. Seasonal staff, many of whom started working there as teens and have come back for twenty or more years, cut down the trees and shake them with the Lit’l Shakee tree shaker to evict any loose pine needles, small creatures, beehives or abandoned bird nests that may be lurking within the branches. The experience sure beats picking up a tree in a parking lot along the side of the road.

“We sell about one thousand trees each year,” said Rollie. “Things get really hectic around here from Thanksgiving to Christmas.”

Conservationists and activists began to worry about the future of the bucolic farmland in 2002 when Roland Sr. sold seventeen acres to developer Marc Ginsburg for $1.9 million to build the thirty-five-home Enchanted Forest subdivision.

In exchange for the Chapter 61A tax break, the city was granted right of first refusal when the decision was made to sell the land.

Calvin said her organization was not mature enough at the time to take on such a large

8 The Lowell Review 2023

project and the price tag was too steep.

“We knew the same developer was interested in more of the land so that was always in the back of my head,” Calvin said. “We knew that was always a threat.”

She was not going to let another shot at preserving the land pass her by. In 2018, the LPCT teamed up with Mass Audubon and Mill City Grows and worked with Rollie throughout the pandemic to reach a deal that would make everyone happy.

Calvin said there are not too many urban land trusts in the country and to be able to preserve a piece of land like Rollie’s, which borders an 1,100-acre forest, is almost unheard of and a dream come true.

“I want people to come here and feel welcomed, to walk the property and enjoy it,” she said. “Every kid in Lowell should experience this property.”

It is a natural progression and perfect location for the three organizations to expand their offerings. LPCT and Mass Audubon have a long relationship running after-school and other programs in Lowell, including at nearby Hawk Valley Farm. Mill City Grows runs two urban farms, eight community gardens around the city, and built and provides educational programming at sixteen gardens at Lowell Public Schools.

Mill City Grows will cultivate vegetables reflective of the cultural diversity of Lowell on the lower ten-acres of Rollie’s property, and there are plans for a food forest with fruit trees and other plants that require less tending on the land between the fields and the upper acres of the property. The food forest will be a space where visitors can wander, pick themselves a healthy snack, and learn about where our food comes from.

“Part of our mission is also to connect people to the land, and this is the single biggest project we have ever taken on—preserving this beautiful space to be in service to the people of Lowell for the rest of time,” said Wilson. “I want this to be a space where everyone has access to healthy, sustainable, and culturally connected food, and people are defining and creating their own food production systems. That will make us a more resilient community in many ways, and we will have our own food, a cleaner environment, and strong ties to our neighbors.”

While Rollie admits it is going to be difficult for him to step away from the farm, he is looking forward to playing more tennis and getting back to drumming more in future years. He has found peace in knowing that he is leaving the land and his family’s legacy in the capable hands of organizations and people who share his values and will continue to make the space one of the city’s greatest assets.

The Lowell Review 9 2023 Section I

Owl Winter

carla panciera

The ancient Romans believed that a feather from an owl revealed the secrets of a sleeping person.

It is January. My daughter will turn nineteen. Apphia likes to talk, will sit on the edge of my bed the way I sat on my own mother’s bed, and provide details of her day. But, of course, she is, as I was, as my mother was, a keeper of secrets. Why would I want to know these, when some of what she tells me is hard enough to hear?

This has been an owl winter. Apphia asks if I hear them. I don’t, so, the night before her birthday, I lay awake listening for them and waiting for those moments when Apphia needs to talk and tells me that she isn’t afraid of death, only of everything that comes after it for the living. Or that she explains how her best friend, someone she has loved since she was three years old, has left her out of things deliberately, has decided someone else is her best friend now. But Apphia isn’t surprised or wounded, only practical. She’ll just explain to her: I’m okay not being with you right now. She will say something similar to her first love. “I can be alone,” she says.

She has held all three of her grandparents’ hands this year as they have left her. She isn’t afraid of endings.

When I was a teenager, I didn’t tell my own mother that I was friendless. Of course, she knew, but if I had said it out loud, she would have had to tell me her own secret: That she blamed me for it.

In December, Apphia ran with her father over trails covered in flattened leaves. Sometimes, she broke through a crust of moss partially frozen, stumbling, not looking down as I would have looked down, not slowing as I would have slowed. She felt something. Or saw something. Maybe movement, a bigger shadow than crow or hawk. The barred owl perched on a branch. So she got a good look, the swiveling head, the yellow beak. Even when she called for her father, the bird stayed, lifting away only when Dennis finally turned.

The day after she saw the owl, she took me to the trails. I concentrated on my steps, forgot running and then paid close attention to where I placed my feet, the way, as a family, we had paid attention to breathing, to the way a body starts to cool, limbs first towards the center.

I had no faith the bird would reappear, until Apphia pointed to a blurred brown form on a bare limb for an instant before the creature disappeared.

It’s not an owl’s body that is large. It is the wings, fringe-like, silent. On the way out of the woods, Apphia reached down and picked up a pellet, furred and feathered, pierced with bones. An owl eats its prey head-first. Swallows it whole.

My mother has been dead one year.

Apphia has inherited the compulsion to dream-share in the glare of the morning sun. From my

10 The Lowell Review 2023

grandmother who dreamed in Italian. From my mother who translated for us, then told us of the dead people who reappeared in her own dreams, people she might never have spoken to in real life.

During pregnancy, nightmares plagued me. My uncle who ferries souls to the next world appeared.

“I know why you’re here,” I said, standing in a kitchen where the women in my family prepared a meal at the counter and did not see him. I wanted to hold my belly the way women in movies do, but my hands were folded in prayer.

The next night, the dogs woke me barking downstairs. What kind of an owl was it that sat on a branch outside the kitchen window, that stayed, unperturbed by the noise? A cold and snowless night. A waning crescent. The unmistakable bird.

“I know why you’re here,” I said. Awake, I could hold my belly and feel the baby’s response.

My mother tucked a plastic bag of salt and a silver dollar into a diaper the first time a baby visited her home. “A blessing,” she said.

Birds flying into the window, new shoes on the table, bad luck. “Dreams of babies too,” she told me. “But dreams of the dead? Just the opposite.”

“What about birds who don’t fly into windows? Who just watch?”

She had no answer. Or she did but kept it to herself.

“Do you see why I had to end things, Mom?” Apphia said. I was driving north along old Route 1. We had a few more presents to buy before Christmas. “Do you understand why sometimes, friendship ends?”

Do you remember, I didn’t say, what I told you about the dissolution of my own friendships? Those two women who never came back? I had no idea what friendships required.

Apphia and I were in the middle of an intersection where each summer, beachgoers on their way to Hampton bought towels displayed on clotheslines strung from a van to the trees on an otherwise desolate lot, an unsightly stretch by an abandoned gas station opposite it.

I did see. Because you can’t be what someone loves. Because you don’t like the songs they like. You wear the wrong jeans. You say things you don’t mean but only out of fear.

It’s just that you’ve lost so much already, I wanted to say.

Then, we noticed the small group gathered beside the rusted gas pumps. Birders with scopes and cameras.

“There!” Apphia said. The second barred.

In the middle of our stories, in the middle of our day, in the middle of nowhere, we studied the creature and then its likeness captured by a stranger who scrolled through her images so we could see its expression. Black eyes. Unfazed by traffic and blight, a mile away from the New Hampshire border with its plethora of shops selling fireworks.

“There’s also a screech in Rowley. Todd Farm. Can’t miss it,” the woman told us.

We live in Rowley. So in the middle of errands and explanations, without what we’d come for, we headed home.

The Lowell Review 11 2023 Section I

Apphia’s first dream (three years old): “There was an owl in a tree. A purple one that spoke to me.”

“Were you afraid?” I asked.

“No.”

We can’t appropriate a totem, we can only ask for it to reveal itself or notice its repeated presence. For the ancient Greeks, the owl symbolized prophecy. Wisdom. What strikes me is how they watch. How we might miss them watching.

In the grocery store, toddler Apphia would lean against my leg as I unloaded our cart and tell me people’s names. People she had never met. “But I was listening,” she said. “I saw their lips moving.”

One time, just as I reached over her bed to turn out the light, she said aloud my father’s name: Aldo. She never knew him and most people used his nickname. She said nothing else, only settled in to sleep.

When she does wake me up from my own dreams on the eve of her birthday, she says she can’t sleep because she didn’t know people died with their mouths open.

In search of the screech owl, we pulled into the former farmland, fallow pastures like dusty fairgrounds surrounded by new growth forest. The barn housed an antique shop. A car was parked outside where cows once plodded in to be milked.

“We’re to believe an owl will be just sitting in a tree? It can’t be that easy,” I said as we made a slow arc of the property where, every warm Sunday of the year, bargain hunters roamed aisles of a large flea market.

I got out and paced a stretch of woods scanning trunks and branches, wondering what I should be looking for. Apphia never had to seek the birds.

“I’m sorry,” I said, when I got back in. This is how things go sometimes, I wanted to say, but she knew that. People can disappoint you and still love you. They can leave and never return and you will have a day like this when you are out in search of cleaning supplies or potting soil or a lightweight sweater and, instead, you see something up close that you’ve never seen.

I paused at the exit to pull back onto the road, and Apphia touched my arm, pointed to an impossible iconography. In the hollowed oval of a tree, the screech owl. The Virgin’s profile caught in clapboards stained with rot could not have so inspired our adoration.

At the end of her life, my mother returned to the church.

“I know you think it’s voodoo,” she said. “But it’s a luxury to know you’re going to die. To have time to make your peace.”

After all three of our parents had died, Dennis and I divided up their rosary beads. I took none. Apphia waited patiently for her string.

Apphia caught everything when she was a girl—frogs, newts, mice. She sat for hours waiting for a snake to come out of a hole in our foundation, stood still enough for fish to nibble at her ankles before she scooped them into a bucket without a net. She asked why she couldn’t catch birds. “They have wings,” I said. “They are too fast for us.”

But one day she uncupped her hands just wide enough for me to see the sparrow. “It let me get it,” she said.

12 The Lowell Review 2023

What my mother told me when I was a child: “You’re too impatient for everything. You want and want and never let things just come.”

Seeing an owl might suggest it is one’s spirit animal, a guide that allows one to see beyond the world’s illusions. Or it is the spirit of a wise person who has come back to protect loved ones. Or only that it has been disturbed from its normal routine.

On the day of her birthday, Apphia’s boyfriend was late because he was playing street hockey with boys he sees all the time. He didn’t call, and it was not the first time she’d waited for this sweet, handsome, sometimes thoughtless boy. She is not the kind of girl who cries.

Last year, he bought her silver bird earrings, tiny posts for one of her piercings. She has never removed them. Even when she said she was ready to move on.

“It isn’t that I don’t love him,” she told me. “It’s that you can’t fix some things no matter how much you love someone.”

Some believe owls, like Tarot’s death card, represent change, death of the old life, transition. From the time, for example, that you get a young man who loves you to join your high school’s new birding club, to the day you take him to see the screech owl a mile from your house on one of your last days together.

The night after her birthday, when Apphia climbs into my bed, I ask her: “How do you always see them?”

She thinks so long, I wonder if she is sleeping. But then she says: “I feel the shadow passing,” to a mother who lives with metaphors.

“Nonnie thought if I had a craving when I was pregnant and I didn’t answer it, you’d get a birthmark,” I say. “She had a lot of crazy ideas. But look how perfect you are.”

“It’s good when you hurt this much when people are gone,” Apphia says. “It means you loved them.”

The same can be said for how much you forgive them for, or fear for them, but she is here now while out there, the owl is waiting to guide her, or keep her safe, or just listening for its prey.

“Mom,” she says. Her face is turned towards mine so I can feel her breath. “I changed my mind. It’s not the shadow passing. It’s the bird. Even in the dark, I know it’s there.”

“And you’re not afraid,” I say, and she says, “What is there to be afraid of?”

The Lowell Review 13 2023 Section I

Eulogy for a Sugar Maple

emilie - noelle provost

When we moved into our house ten years ago, one of the things we liked most about the yard was the large sugar maple tree growing beside the driveway. I could tell the tree was old by the thick, rough bark covering its trunk. Countless snowstorms and decades of wind and rain had caused the tree’s limbs to become gnarled and twisted. During the fall and winter, when the tree was bare, it had a spooky appearance that reminded me of the 1993 animated film, The Halloween Tree, a fantastic children’s trick-or-treat story based on a novel by Ray Bradbury.

Although many of them still sprouted leaves, some of the sugar maple’s older branches had partially died and become hollow. These, along with a few large holes high up on the tree’s trunk, had been adopted as nest sites by generations of gray squirrels, blue jays, downy woodpeckers, nuthatches, and screech owls. A hole in the lower part of the trunk, marking the spot where a limb had once been, was home to a family of chipmunks.

During the warmer months, we enjoyed watching baby chipmunks—adorable little things—pop out of the hole and chase one another up and down the tree. They would sometimes do this for hours, which always made me anxious that a red-tailed hawk—also among the tree’s residents—would swoop down and snatch one of them up.

In the heat of summer, the sugar maple’s wide canopy provided a shady resting spot for the cottontail rabbits living behind our garage. On hot afternoons, if we were lucky and very quiet, we’d sometimes spot a couple of rabbits relaxing on the grass beneath the tree. Seeing these normally skittish animals sprawled out on the ground, grooming themselves, always made me feel lucky.

The sugar maple’s bright red and yellow leaves were one of the best things about autumn at our house. They began to turn color in mid-to-late September, usually before the other trees. In the early fall, the tree’s beautiful foliage was often the first thing I saw each morning when I rolled up the shades in our bedroom.

It was during a ferocious nor’easter in late March 2018 that one of the tree’s heavy limbs broke free and landed on my husband’s new Ford Focus. It happened late at night and over the howling wind sounded like a moving car slamming into a brick wall. In the morning, when the sky had cleared, we saw that the branch, which was about fourteen feet long, had smashed the car’s rear window and had made enormous limb-shaped dents in the roof and trunk lid.

Although the car was drivable, our insurance company totaled it. It wasn’t all bad, though. We got enough money to pay off the loan. And since we both worked from home, we decided to see how we would fare with one car instead of two. It worked out so well and saved us so much money that we own only one car still.

We cut up the fallen limb for firewood and clipped off several of its thinner branches, all of them swelling with spring buds. We arranged the branches in a large vase filled with water and enjoyed a bouquet of fresh spring leaves as the centerpiece of our Easter table.

The Lowell Review 2023 14

After that storm, we began to worry every time the wind picked up. There was no telling if, or when, another limb would fall from the tree. We began parking on the opposite side of the driveway, as far away from the maple as possible. If people came to visit, we’d encourage them to park beside the garage, out of the way of the old tree.

But with more storms came more downed limbs. More than once we arrived home to find a large branch in our driveway, always grateful that we had been out when it came down.

One night last fall, one of the tree’s largest boughs broke off and landed on the roof of our neighbor’s garage. Fortunately, it didn’t cause much damage. But the message was clear: The tree needed to come down.

I had to leave the house when the tree service began removing the maple’s knotty branches. I couldn’t bear the sound of the chainsaws.

Hours later, our driveway covered in sawdust, a vast hole had opened in the sky. A single gray squirrel paced back and forth along the eaves of our neighbor’s garage, searching in vain for its lost home.

In the next few weeks, we’re going to plant a new tree in the spot where the sugar maple stood. We’ve considered different kinds of trees—some tall, some squat, a few with delicate spring flowers. We still haven’t decided which one will work best, but I’m beginning to think a young sugar maple might be just right.

The Lowell Review 15 2023 Section I

Environmental Youth Task Force: Smithsonian Institution Trip

Members of the Environmental Youth Task Force in Lowell, ages fifteen through twenty-one, make a difference through conservation action, advocacy, and community events. Building their skills and knowledge, they work with scientists and decision-makers on environmental projects. They work alongside leaders from the Lowell Parks & Conservation Trust, Lowell National Historical Park (LNHP), Tsongas Industrial History Center of UMass Lowell and LNHP, and Mass Audubon. Following is a report on the group’s experiences in Washington, D.C., at the invitation of the Smithsonian Institution.

We are the Environmental Youth Task Force (EYTF) from Lowell. We were invited to Washington, D.C., in June 2022 by the Smithsonian Institution for their National Folklife Festival. While at our booth, we reached out to others through the Earth Optimism portion of the festival, a special area dedicated to climate change. We interacted with the public and spoke about all of the incredible work that our group does.

One amazing part of our booth was our pollinator garden signage. In the fall of 2021, the EYTF started a beautiful pollinator garden at Jollene Dubner Park. One area of the park was littered, polluted, and overgrown. It was an amazing opportunity to transform an unnoticed part of Lowell. We then created signage to bring awareness to our garden and why it was there. It was such a wonderful experience to share with many interested people! Below are accounts of personal experiences of EYTF members who visited the nation’s capital.

Kevin Hankins (Innovation Academy Charter School)

Washington, D.C., provided us an experience found nowhere else. We shared information about ourselves and displayed a model of a watershed called an EnviroScape, a crucial part of our exhibit and a conversation piece. The bright colors and unique design prompted discussions about watersheds and why protecting the environment is essential. Meanwhile, others came to our information table and became invested in what we stood for, asking countless questions about where we were from, what we were about, and things we had done as youth in action for climate change. This experience allowed me to expand my public speaking skills. I was able to open up and talk to strangers about myself and our wonderful group. The experience altered the way I approach the world.

16 The Lowell Review 2023

Kiran Maharjan (Lowell High School)

Our trip to D. C. was a unique opportunity. It’s amazing that we got to reach out and communicate with people on a national level. While there, we met local youth groups that are also focused on Earth Optimism. We even met our local Congresswoman, Lori Trahan! Our Folklife Festival booth got plenty of foot traffic from supportive passersby who were interested in the EYTF and the environment. We had a scavenger hunt with stickers and props to demonstrate pollution that trickles down into local watersheds. We also had an opportunity to speak on a panel about youth activism and local problems today, such as climate change, poor public transportation, and making a difference in our community.

Noah

Logvin (Middlesex Community College)

My experience at the Folklife Festival was fantastic. I feel so lucky to have been there. It was amazing meeting so many people from so many walks of life, and lots of other environmental groups. It felt like such a growing experience to be running the information table myself. It has made me much more comfortable with public speaking. As a group we had some unique (and confidential!) behind-the-scenes opportunities with the Smithsonian museums as well. These experiences were very special.

Daniel Guerra (Middlesex Community College)

Even though I got pretty dizzy during takeoff, my first time flying went surprisingly well, mostly because the beautiful scenery of New England/D.C. stopped me from passing out. On our first day, we visited the Smithsonian Zoo and learned about various animals. At the Folklife Festival we used an EnviroScape, which is an interactive model of a watershed to teach children about pollution and the effects of runoff. It was mostly kids who used the Enviroscape, but we got to meet a lot of different people. After we finished our work and trips for the day, we went to the Renaissance Hotel for the night. For the next three days, we split up shifts for hosting our tables so that everyone could get breaks. We went to museums such as the labyrinth-like Asian art museum with its ten-plus underground floors and the natural history museum. It was a great experience, and I can’t wait to go again to learn more about so many different cultures!

Throughout this trip we had many ups and downs with the travel, hotel, and much more, but it was completely worth it. This was such an amazing experience for EYTF. It was also so amazing to have shown off our pollinator garden signage. Our project at Jollene Dubner Park was a huge accomplishment for us! I enjoyed D.C. and its wonderful history along with its museums. I am so thankful to the Smithsonian for sharing this with us and having us be a part of their amazing festival. I am also very thankful for getting the opportunity

The Lowell Review 17 2023

Jasmine Puga (Greater Lowell Technical High School)

Section I

to meet our Congresswoman, Lori Trahan, who had a busy schedule. We told her about our work in Lowell and what we were doing at the Folklife Festival.. It was truly unbelievable that we had the chance to speak with her. It was an unimaginable moment for us!

Conclusion

Our trip to Washington, D.C., was an incredible time! We are thankful to the Smithsonian for inviting us. Our optimism comes not only from our pleasant experiences at the Festival and our environmentalism, but also from the concrete facts. We can make societal changes, we can give people the hope they need in dark times, and we can come together to solve problems. With enough earth optimism, it’s possible to pull through climate change while building a better future.—The EYTF

18 The Lowell Review 2023

Tomorrow There Will Be More of Us:

An interview with Brad Buitenhuys of the Lowell Litter Krewe (Spring 2022)

babz clough

Tell me about yourself.

I grew up not far from Lowell and realized I could graduate high school a semester early, but I needed to have a plan. I applied for AmeriCorps National Civilian Community Corps (NCCC) for ten months of national service. While waiting to join, I worked with a carpenter in Reading who put me in the basement of an old Victorian house. He told me to pull out all the concrete and then dig out six inches of dirt, and then they were going to repour the concrete. It took me months but that was the beginning of my construction experience.

Joining AmeriCorps accelerated the construction thing. By the end of ten months, I had worked on 100 homes and built playgrounds mostly in the Gulf Coast area. Volunteering became something that made me happier than anything. I joined AmeriCorps to travel and to try and find a home, but I didn’t know where it was going to be. I traveled—New Orleans, Sacramento, Phoenix, Biloxi, and a few other places along the way and then came home and enrolled at UMass Lowell. Since then, I’ve been a construction manager, surveyor, civil engineer, and a carpenter. Lowell’s been home for thirteen years and I don’t see that changing soon.

Having been here this long, why now for the Lowell Litter Krewe?

The idea came from the Lowell Canalwaters Cleaners. I’d been volunteering with them pretty regularly as they clean waterways throughout the city. I loved doing it, and I loved hanging out with them. But I knew there had to be more people interested in volunteering and I wanted to share the passion and love that I have for it.

So I just thought: “I’ll add one more event each month.” Every two weeks seemed doable, and everyone would come clean up on one other Saturday. But way more people showed up and we did so much more than I thought, and everyone said, “What are we doing tomorrow?”

And that’s how it started.

How did you initiate the group?

I started with Facebook. On EforAll Merrimack Valley there was a post on a Lowell Live Feed Forum about a little triangle of grass behind a local business. One person posted, “It looks terrible, I need help, it’s too much for me to do alone.” So, we set up a meeting and

The Lowell Review 19 2023

Section I

posted it on Facebook. Thirty-five people showed up. We cleaned there, and then down to the Lowell Connector, some of the backroads and neighborhoods, and just kept going. We had a blast and it looked so much better. And we had a giant pile of trash.

It’s more fun picking up trash with other people—I don’t like to pick up trash alone. Turns out there are lots of people who have more fun with other people, but there are lots of people who are picking up trash on their own. It helped that there were some elected officials at the very first clean-up, so we received a lot of support from the city.

Do you think part of the interest was your timing because you started in March 2021, in the middle of the pandemic, and people wanted to just get outside?

Yes, we did one event in the fall of 2020. Then we started every Saturday beginning on March 13, 2021. We did almost every Saturday in 2021 until it got so cold it was miserable. We tried in November, an hour at the YMCA on Thorndike Street, getting rained on, almost freezing and yet twenty people showed up. We had seventy events the first year. We were coming out of the pandemic, coming out of winter. People wanted an opportunity to rekindle community—our city didn’t look good.

Do you ever find yourself getting discouraged when you have to clean the same area repeatedly? Or are you seeing less to clean up?

I have gotten better about not taking it personally, but I also believe it’s happening less and less. There are always places that don’t keep themselves as clean as you’d like. That little triangle we did: took all day the first time. In the summer, three people spent thirty minutes, and it took me fifteen minutes in the fall. Now I could do it in five minutes. If we keep somewhere clean, it stays clean for longer. It’s 100 percent the broken-window effect. The neighbors are taking the hint and fewer people are throwing things on the ground.

How do you get connected with other organizations?

People reach out to us. Hosting huge, fun events that people keep coming back. People that are in networks of other groups.

So, attraction rather than promotion?

Yes, with community groups, nobody should be forced to volunteer. There are 600 devoted volunteers who have come out and picked up trash. That’s 600 unique volunteers. We keep track of people who come to the events, and who’s a new volunteer. We’ve over 1000 followers on Facebook and a similar number on Instagram.

There are two phrases you use which always make me smile. Tomorrow there will be more of us is emblazoned on the vests and seems a self-fulfilling prophecy, but what about the second one.

We can have nice things: It’s the broken-window effect. What’s under all this trash? That’s why I got the giant speakers for the truck, so people notice us. You can’t have nice things if you’re going to break them. I love this city and I want people to love it as much as me.

What’s the draw of Lowell for you?

Big food guy. Love being able to eat all the great nationalities and cultures from around the

20 The Lowell Review 2023

world. I’m happier out here in my cut-off shirt and shorts with holes in them. I’d rather be able to go without shoes but can’t do that. In college, I lived in Fox Tower. I walked across the front lawn in fresh snow in my bare feet one winter. And then it iced and stayed cold and frozen. You could see my frozen footprints for weeks. Everyone knew it was me.

Where do you see Lowell Litter Krewe going in the future?

Our mission is to support volunteer opportunities and create more volunteers. Our focus is on redevelopment of underutilized open space. We want to find willing investors into public land so we can develop our parks, make them more attractive and places where people are safe and want to spend their time.

People complain, “The kids aren’t going outside enough.” If we can find some inspirational, connective aspects for our public spaces and parks, bolster our playgrounds, and enhance our river walks, we all benefit. The city is making huge strides in these areas, but as a separate group we can take on passion projects rather than “have to” projects.

We can make little wonderlands in all our neighborhoods.

Because the city has to focus on the big projects, there just isn’t the support for all the little projects. But kids live all over the city, and every kid wants to play on a cool playground.

Is there a plan for an adopt-a-neighborhood program or adopt-a-park program?

Routine maintenance is something we try to avoid. Adoption and stewardship are critical for the long-term success of the city. We offer to come in and do the first round of cleaning, but then we hope people will just adopt streets and parks. Look at Vanna Howard’s Adopt-a-Street program downtown—she has thirty-five volunteers on all of our streets downtown. We want to replicate that in other neighborhoods. We’re trying to source funding so anyone who wants to adopt a street in another neighborhood can get a picker and bucket. It shouldn’t cost money to volunteer.

What do you want people to know about LLK?

The spelling of Krewe is an homage to the second-line Indians of Mardi Gras. The krewes are Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs. We try to inspire our little trash band. It’s easy exercise and people can come out and meet neighbors who care about their city. There’s no category that we all fit in, other than that we care about this place. It’s not young/old, liberal/ conservative, rich/poor. We just want there not to be trash on the ground.

Anything else?

We’re super excited to be starting our work with significant funding from the state delegation via the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) fund on the Centralville River Path. Our first major construction project will be at Gold Star Park. Thanks to the community outreach by DIY Lowell, part of Coalition for a Better Acre, we will be doing as much as we can to construct the collective vision of the community for this place. This is not just one person’s dream but the community’s. We envision grading the trailhead to the American with Disabilities Act (ADA) standards, so it stops eroding every year and it’s safe for people to use. We want to make the park more open and welcoming with a better view towards the river, so people feel safe. We’re going to add a pergola and seating and start connecting the other side of VFW Highway to the river.

The Lowell Review 21 2023

Section I

Who else do you want to give a shoutout to?

Coalition for a Better Acre, Lowell Canalwaters Cleaners, Lowell Dept. of Public Works, EforAll Merrimack Valley, and of course, the Lowell Litter Krewe Board: Karonika Pholy, Ami Hughes, Adam Roscoe, Tara Hong.

Statistics:

2021 (full year)

112,600 pounds of trash

4,174 volunteer hours

71 events

2022 (Spring)

48,600 pounds of trash

1,426 volunteer hours

43 events—and it’s not yet summer!

22 The Lowell Review 2023

Book Review

The Climate Book: The Facts and the Solutions

by Greta Thunberg

(Penguin Press, 2023, $30)

The book is as thick as a Harry Potter novel, which makes sense coming from Greta Thunberg’s generation. At 464 pages, it’s more a toolbox than a compilation of high-level analyses of global warming. Reminds me of The Whole Earth Catalog from Stewart Brand or Our Bodies, Ourselves from the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective, being an operator’s manual. Like Thunberg, the book is no nonsense, just the facts and instructions on best practices for dealing with climate change.

I can picture millions of young people hauling the paperback around in backpacks at school or on the road. Robert Pirsig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance was called a “culture-bearing book” of the 1970s, but Pirsig is cerebral as he writes: “The real cycle you’re working on is a cycle called yourself.” He’s seeking a coherent life in the face of rapid technological change. Thunberg’s book is also a response to technology that has altered life on Earth. She has created a super-sized Swiss Army Knife for an immediate climate crisis response. She’s crying “Fire!” on a crowded planet.

Thunberg is more than the celebrity activist, self-taught, who launched her school strike as a climate alert in Sweden some 230 weeks ago as this magazine hits the street and web. She’s a household name and just twenty, known for her stark warnings at the United Nations, World Economic Forum, and U.S. Congress. In 2021 she “invited a great number of leading scientists and experts, and activists, authors and storytellers to contribute” to this “comprehensive collection of facts, stories, graphs, and photographs showing some of the different faces of the sustainability crisis with a clear focus on climate and ecology.”

The book is aimed at the broad public. Her all-star lineup includes Michael Oppenheimer on Climate Change, Kate Marvel on Droughts and Floods, Lucas Chancel and Thomas Piketty on Decarbonization via Redistribution, Margaret Atwood on Practical Utopias, and Bill McKibben on the Persistence of Fossil Fuels. The contributors deal with glaciers, insects, air pollution, denialism, rain forests, permafrost, health & climate, electric power, the truth about recycling, climate apathy, food and diets, water, and on and on.

Thunberg’s headers for intros to the various sections amount to a List Poem:

“To solve this problem, we need to understand it. The science is as good as it gets. This is the biggest story in the world. The weather seems to be on steroids.

The Lowell Review 23 2023

Section I

The snowball has been set in motion. It is much closer to home than we think.

The world has a fever.

We are not all in the same boat.

Enormous challenges are waiting.

How can we undo our failures if we are unable to admit that we have failed?

We are not moving in the right direction. A whole new way of thinking.

They keep saying one thing while doing another. This is where we draw the line.

The most effective way to get out of this mess is to educate ourselves. We now have to do the seemingly impossible. Honesty, solidarity, integrity, and climate justice. Hope is something you have to earn.”

Thunberg has made a hopeful gesture with her global call to action. It’s late, but not too late to act.

—PM

24 The Lowell Review 2023

A Brook in the City

robert frost

The farmhouse lingers, though averse to square With the new city street it has to wear A number in. But what about the brook That held the house as in an elbow-crook?

I ask as one who knew the brook, its strength And impulse, having dipped a finger length And made it leap my knuckle, having tossed A flower to try its currents where they crossed. The meadow grass could be cemented down From growing under pavements of a town; The apple trees be sent to hearth-stone flame. Is water wood to serve a brook the same?

How else dispose of an immortal force

No longer needed? Staunch it at its source With cinder loads dumped down? The brook was thrown Deep in a sewer dungeon under stone In fetid darkness still to live and run— And all for nothing it had ever done Except forget to go in fear perhaps. No one would know except for ancient maps That such a brook ran water. But I wonder If from its being kept forever under, The thoughts may not have risen that so keep This new-built city from both work and sleep.

from New Hampshire (1923)

The Lowell Review 25 2023

Section I

The Pike

In the brown water, Thick and silver-sheened in the sunshine, Liquid and cool in the shade of the reeds, A pike dozed. Lost among the shadows of stems He lay unnoticed. Suddenly he flicked his tail, And a green-and-copper brightness Ran under the water.

Out from under the reeds Came the olive-green light, And orange flashed up Through the sun-thickened water. So the fish passed across the pool, Green and copper, A darkness and a gleam, And the blurred reflections of the willows on the opposite bank Received it.

from Sword Blades and Poppy Seed (1914)

26 The Lowell Review 2023

amy lowell

Stork sky amber river

gary lawless

Inside the bear there is snow and cold water. Outside, storks fly north, from the desert, bringing good luck.

Everything comes to the river, following a map of amber ancient pine forests, resin flow, rivermouth lagoon. I will return, encased in amber, when the black storks fly home.

Nida, Lithuania

The Lowell Review 27 2023

Section I

Steinbeck and Ricketts on the Coast of Rhode Island

cheryl merz

Their ghosts return on a glorious summer morning filled with plovers and red-winged blackbirds and gulls and waves over sand At this deserted Rhode Island beach.

Their voices are the wind that whispers through the grasses. And they are the deer that gazes solemnly from atop the dune before flicking its tail And running off.

Their souls inhabit the driftwood sculptures that adorn the shore above the water line where they are an entire colony Of mythological creatures Basking in the sun.

But they are most present in the tide pools encircled by blackened boulders dressed in seaweed fringe where conversations tumble from the beaks of gulls that trip happily through the shallows As they scavenge their prey.

28 The Lowell Review 2023

dawn paul

lay claim to a patch of salt marsh and watch the sea call it in, sweep it back like poker chips in a round you lost

a bend in the creek will pile up silt and then fold below an ever-extending bank

which will someday take a tumble huge chunks of mud and grass toppling onto the low-tide flats

sandbars appear, looking like a sure thing until the tide scratches them away grain by grain to the sea

your chart is useless, GPS a decorative item when the shifting marsh calls your bluff and your hull catches in the sucking shallows

you won’t be the first to hop overboard muck slurping your Sperry Topsiders as you drag your boat to open water

don’t be humbled as others ride high while you’re tapped out, mosquitoes biting you dry your luck will turn with the tide

The Lowell Review 29 2023

Chance

Section I

Nature’s Oasis

sanary phen

Tucked away in the corner of urban decay

Lost in the day and sounds of crisp rustling leaves, As the calm gentle breeze softly whispers my name

And lays claim to the wispy loose threads of my hair

Lifts them in the air, drenched in the glow of the sun

Warm light has now spun straw into strands of bright gold

Such sights to behold within nature’s oasis

Whimsical places full of rich scarlet flushed fern

Lush leaves left unturned with hidden treasures to find

Somewhere behind the black shadows and dim moonlight

Dark as the night, spurning life beneath fertile soil

Springing coils of vine skimming the edges of green

Unseen and unheard beyond the winding and whirring

Spinning and spurring of human ingenuity

30 The Lowell Review 2023

No More Silent Springs

john wooding

When Rachael Carson’s seminal work was published in 1962 it generated a new and profound awareness of the plight facing a planet that was rapidly being destroyed by air, soil, and water pollution. One of the major results of the movement was the creation of an annual Earth Day celebration in the U.S. and, later, across the globe.

Earth Day is observed every April 22. Its initial goals were to raise awareness about environmental degradation and promote sustainability. The momentum for Earth Day celebrations emerged out of increasing concern with the threats posed to the environment by a century of industrial development and a growing global population. Following the release of Silent Spring by Carson and the several years of active government regulation and protection of air, water, and soil that culminated in the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the time was right for global recognition of the damages to the world’s eco-systems.

A key figure in this movement’s beginnings was U.S. Senator Gaylord Nelson, a Democrat from Wisconsin, who set out to convince the federal government that the planet was at risk. In 1969, Nelson developed the idea for Earth Day after being inspired by the anti-Vietnam War “teach-ins” that were taking place on college campuses around the United States. Nelson envisioned a large-scale, grassroots environmental demonstration

The Lowell Review 31 2023

Section I “Teach-In

on the Environment” ad in The Michigan Daily, March 10, 1970 / Credit: Bentley Historical Library

“to shake up the political establishment and force this issue onto the national agenda.” He launched Earth Day in Seattle, Washington, in the fall of 1969 and invited the entire nation to get involved.

He recalled: “The wire services carried the story from coast to coast. The response was electric. It took off like gangbusters. Telegrams, letters, and telephone inquiries poured in from all across the country. The American people finally had a forum to express its concern about what was happening to the land, rivers, lakes, and air—and they did so with spectacular exuberance.”

The University of Michigan and its students played a key role in starting the Earth Day movement. In March 1970, students there organized a teach-in on the environment, building on the success of their anti-war teach-ins. The movement grew rapidly. The massive Santa Barbara, California, oil spill and the burning of the Cuyahoga River in 1969; the moving, first photograph of “Earthrise” taken by NASA astronauts on the Apollo 8 mission; and the first picture of the whole earth, all combined with the cultural and political moment of the times.

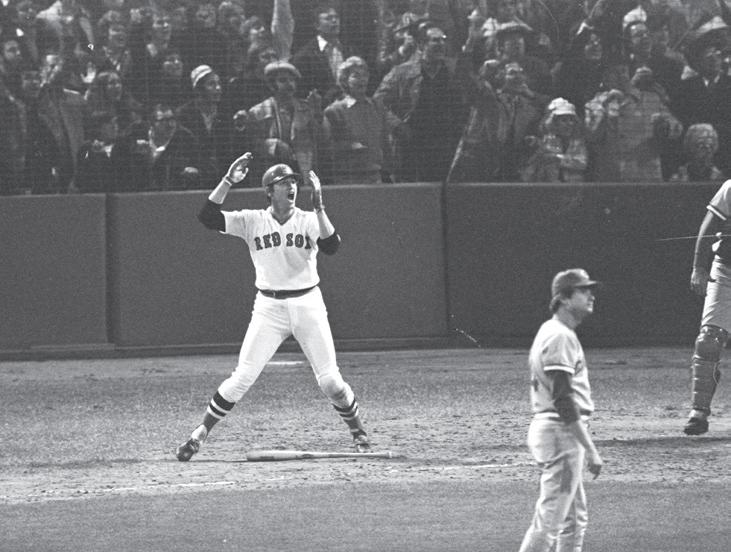

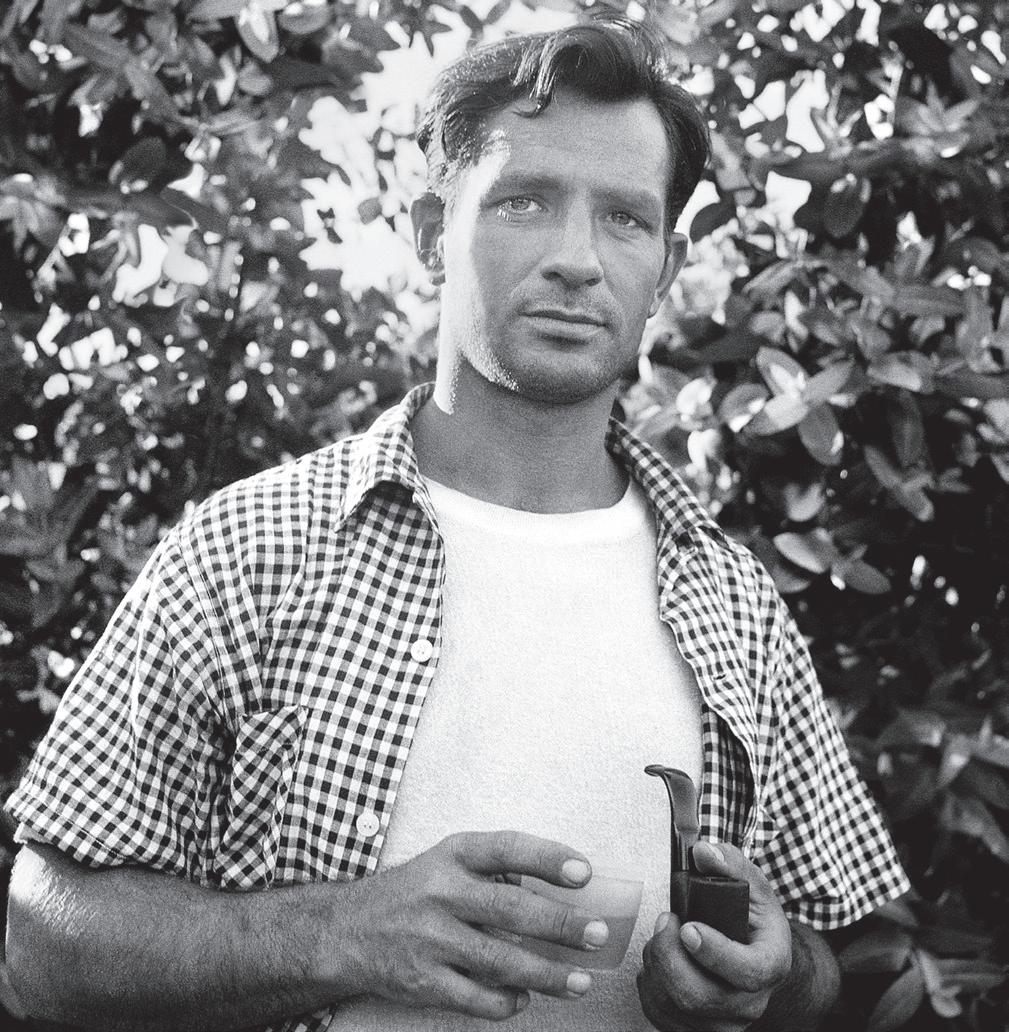

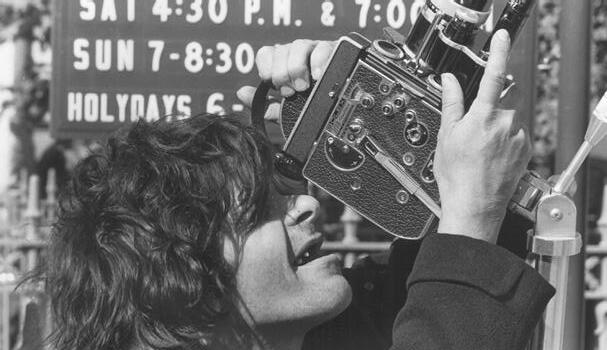

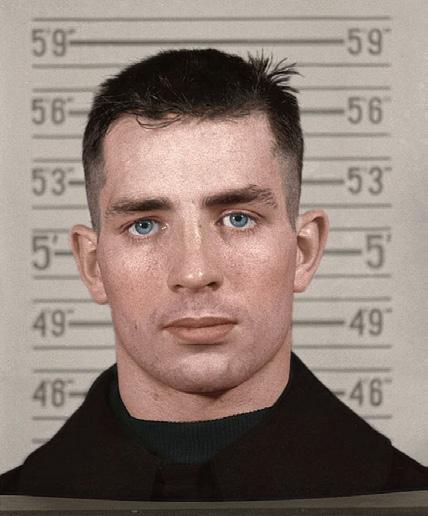

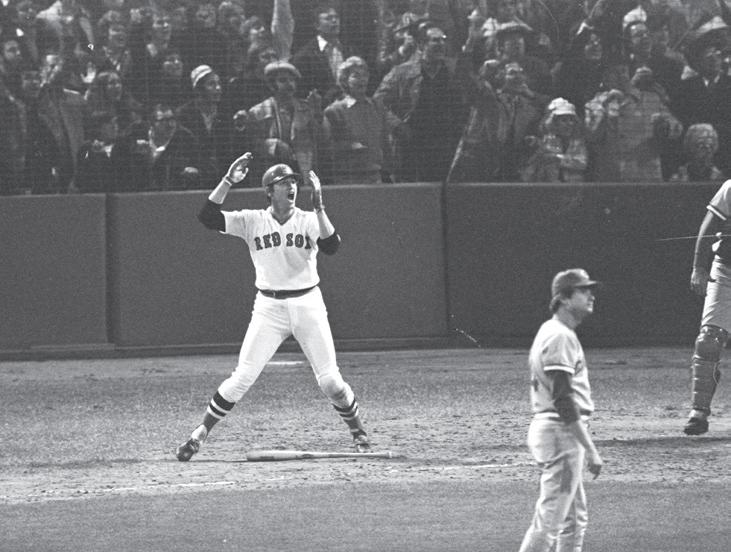

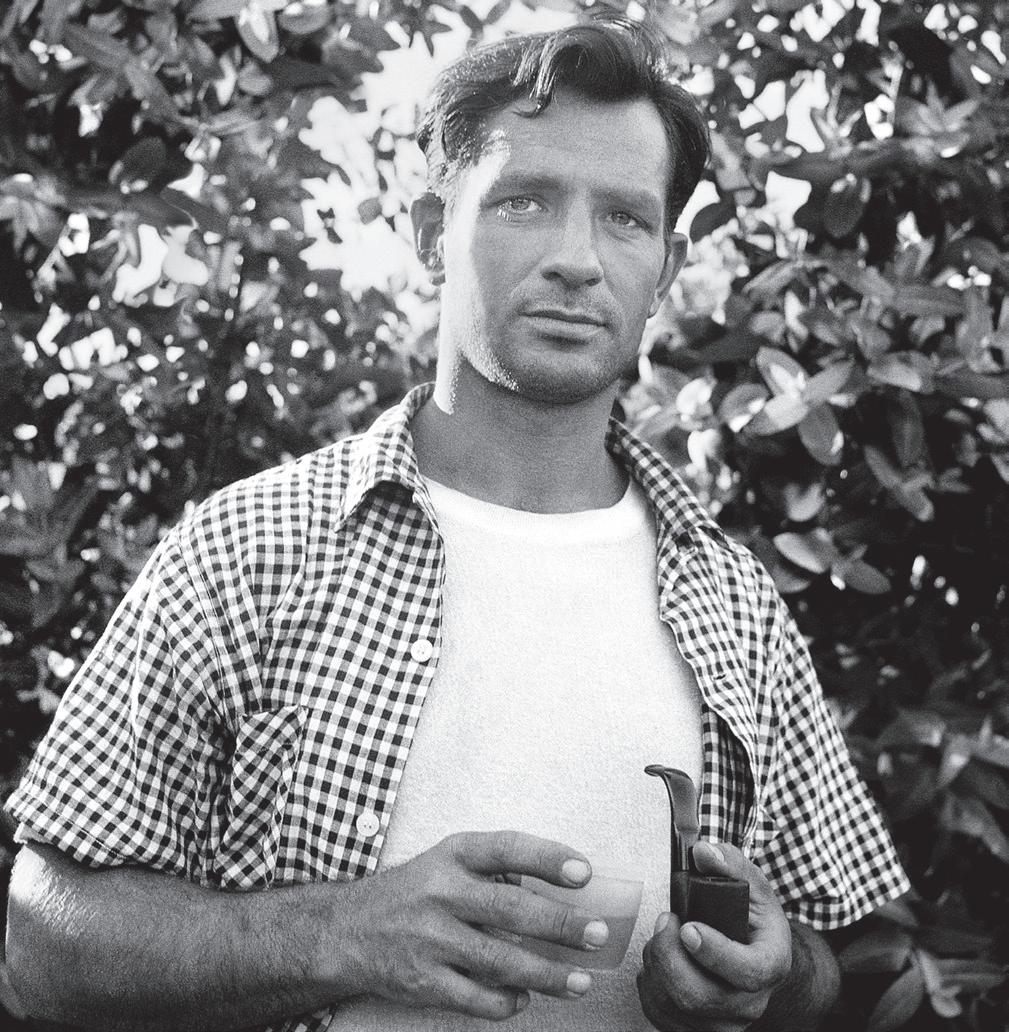

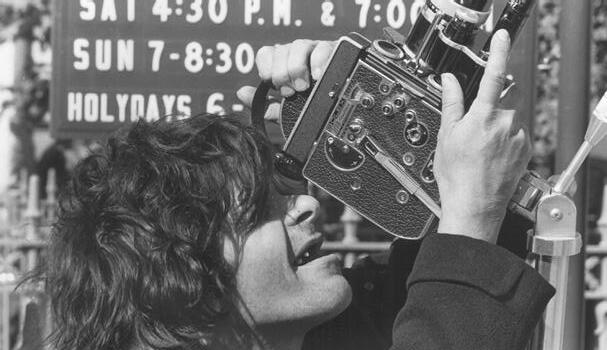

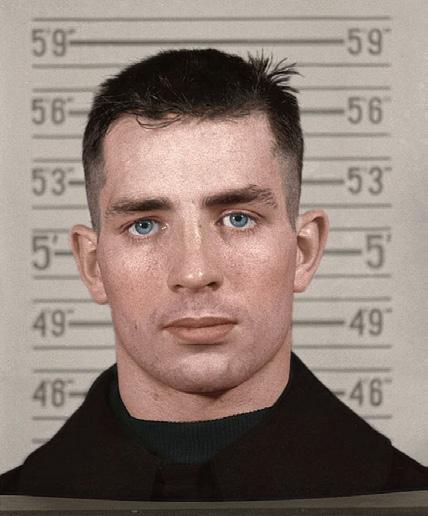

On April 22, 1970, rallies were held in Philadelphia, Chicago, Los Angeles, and most other American cities. In New York City, Mayor John Lindsay closed off a portion of Fifth Avenue to traffic for several hours and spoke at a rally in Union Square where thousands of people listened to speeches and performances by singer Pete Seeger and others, and Congress went into recess so its members could speak to their constituents at Earth Day events.