The Madison Review

Volume 51 No. 1 Spring 2024

ii the madison review

We would like to thank Ron Kuka for his continued time, patience, and support.

Funding for this issue was provided by the Jay C. and Ruth Halls Creative Writing Fund through the UW Foundation.

The Madison Review is published semiannually. Print issues available for cost of shipping and handling. Email madisonrevw@gmail.com www.themadisonreview.wisc.edu

The Madison Review accepts unsolicited fiction and poetry. Please visit our website to submit and for submission guidelines.

The Madison Review is indexed in The American Humanities Index.

Copyright © 2024 by The Madison Review

the madison review University of Wisconsin Department of English 6193 Helen C. White Hall 600 N. Park Street Madison, WI 53706

iii the madison review

POETRY

Editors

Madeline Mitchell

Ev Poehlman

Associate Editors

Jordyn Ginestra

Staff

Brett Dunn

Lauren Goulette

Jasper Huegerich

Carlee Kessler

Vincent Kim

Aamuktha Kottapalli

Maggie Lenar

Syrian Oduor

Alexandra Ruiz

Nyla Sharma

Madison Xiao

FICTION

Editors

Nadia Tijan

Natalie Koepp

Jackson Baldus

Associate Editors

Morgan McCormack

Staff

Alex Gershman

Jackson Wyatt

Dorie Palmer

Taylor D’Andrea

Emma Stueber

Anya Bery

Evan Randle

Priya Kanuru

Anna Lail

iv the madison review

Editors’ Note

Dear Reader,

Welcome to the newest edition of The Madison Review. This edition illuminates the mission we all try to fulfill for ourselves. It is the undertaking of identity. To be seen, see ourselves and to know the freedom of seeing ourselves in others. From within these literary pieces, the characters, writer, and reader converge. All of us, finding ourselves through the chaotic respite of words.

We hope you delight in the poetry, fiction, and art that struck us so deeply in the guts. Please allow our contributors to wield their magic and lay bare the bits of yourself hidden in their work as well. We would like to thank the entirety of our talented contributers for their dedication, care, and skill and for choosing this journal as a home.

We would also like to thank our program advisor, Ron Kuka, for his incredibly resilient patience, boundless wisdom, and unwavering support, along with the UW-Madison English Department and the Program in Creative Writing.

To the staff, thank you for breathing life into this journal. None of this would be possible without your hard work and the curiosity and attention you dedicate to the literary craft.

A final thanks belongs to you, the reader. This issue would not exist without your support. Thank you.

Warmly,

The Editors

v the madison review

vi the madison review

Phyllis Smart Young Prize Georgio Russell |Poltergeist 1 Tournament Time 4 A for AVA 6 Chris O’Malley Prize in Fiction Audrey Toth | Peacock 8 Fiction Jared Lipof | Capt. Hezekiah Coffin 38 Bill Hemmig | Cornflower Requiem 62 Poetry Allison Flory | SUMMER/ STOMACH / SICKNESS 20 THERE IS A WAY TO COMMUNE WITH 26 ROADKILL. Daniel Ooi | Whole 28 Chloe Cook | Brunch with Phoebe 32 Miriam Akervall | Patagium: Having left the Yurt for Gotham City 34 Wave pool: after antipsychotics 36 Daniel Brennan | The birds of Fire Island don’t know that the 48 powerlines aren’t God Ayesha Raees | Elegy::After 50 Isolation 52 Parth Raval | Summer Friday 54 Judith Fox | Changing Gears 60 Logan Anthony | winding with the path 76 elegy for our bodies 78 Annie Przypyszny | Anatomy of Good 80

Table of Contents

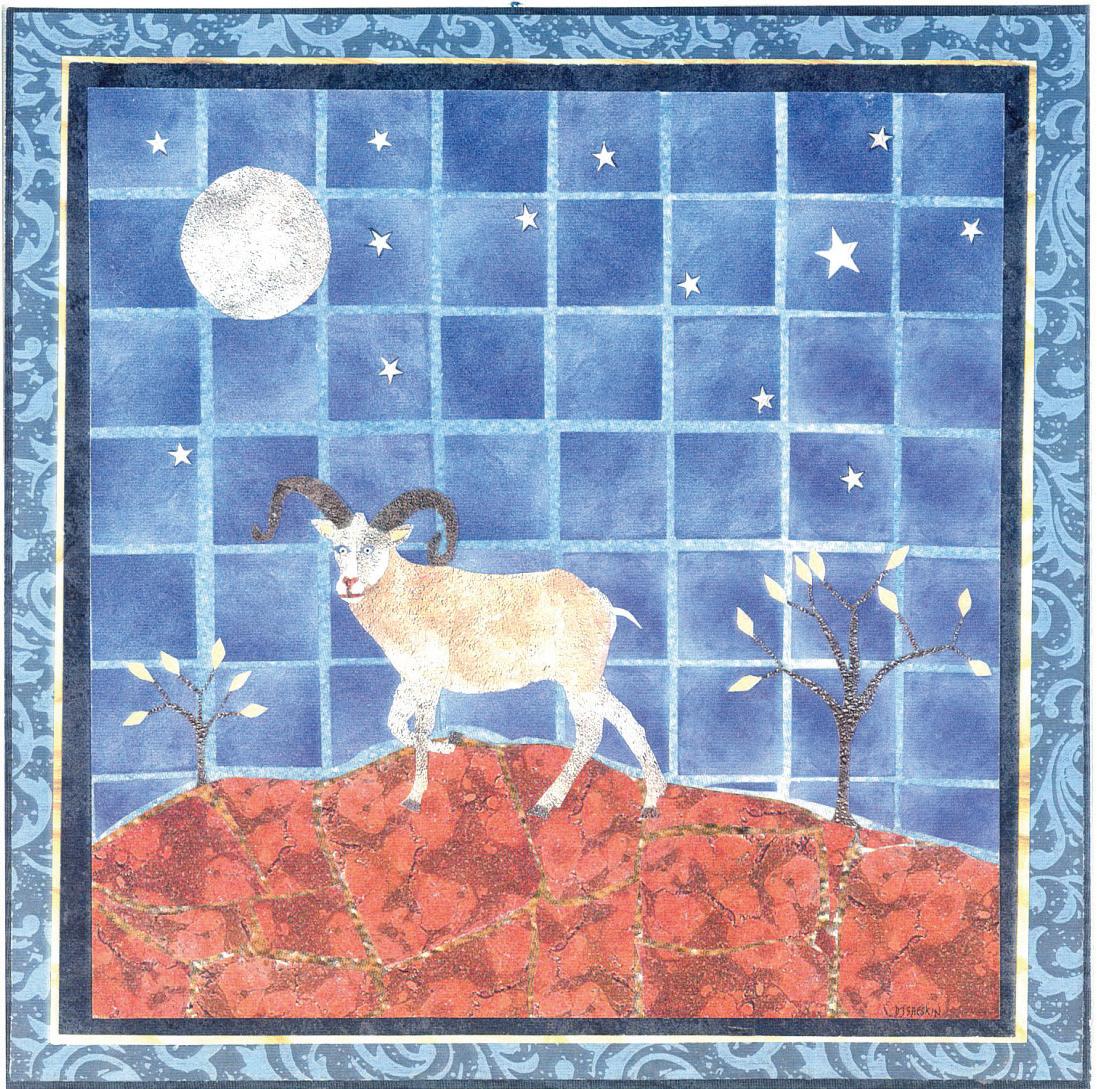

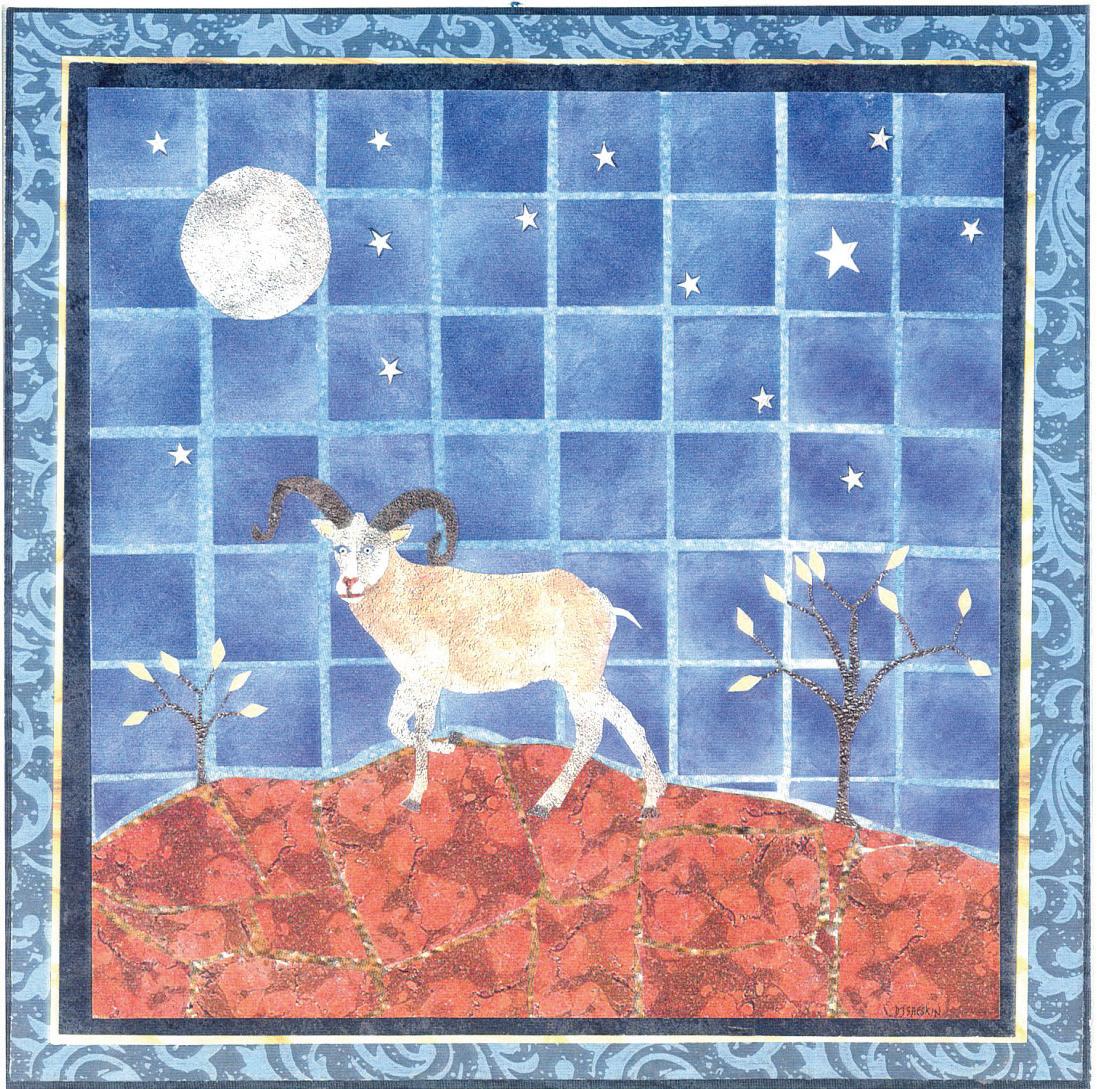

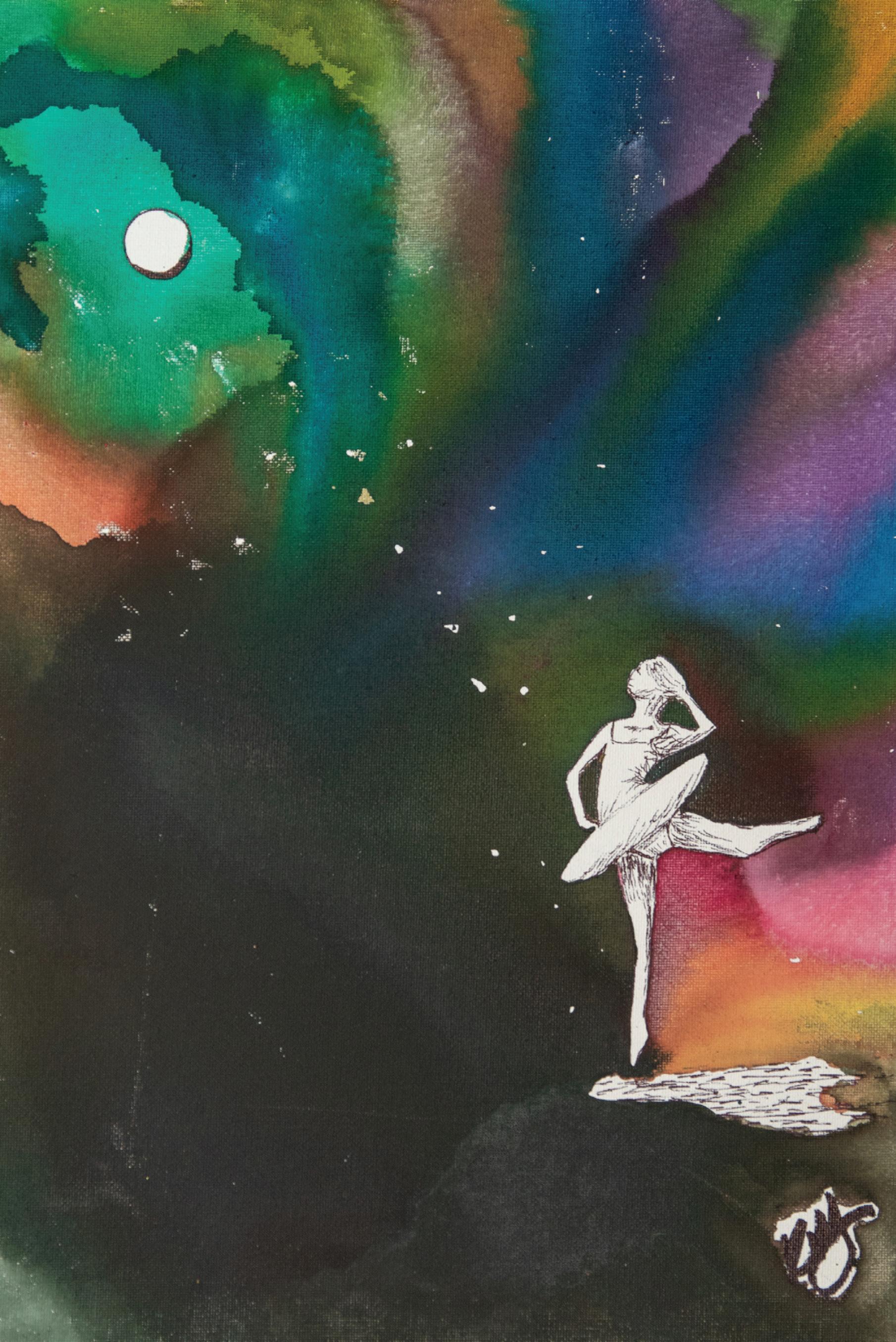

vii the madison review Art Emily Asmann | Eye Wall 21 Sam Downey | Blue 22 Em Von Der Ruhr | Viscosity 1 Silk Has Two Forms (a thematic self portrait) 23 Allison Field Bell | Sappho 24 Artemis 25 Richard Hanus |16 55 18 61 David Sheskin | Textures of Wildlife Zebra 56 Polar Bear 57 Elephant 58 Mountain Goat 59 Contributor Biographies 82

viii the madison review

Poltergeist

Georgio Russell

But this grief, for all its awful weight, insists that he matters.

–Jesmyn Ward

This time again I impersonate the ghost, watching this runty black boy in a jumper run bare-footed down his skinny street at sunset, this boy busy racing his brothers, lagging behind their longer legs while a blue night follows the passages of wind their bodies weave, they are bolting toward me, the specter who is standing beside a rusting stop sign, my hologram unseen by these three who juggle their breath now, arms akimbo after their little olympic labor — the winners will soon pummel their pretty brother into the dewy grass for coming last, then buoy this bruised boy with laughter below lamplight on the brief bike ride home — this is where the image fizzles for today, a polaroid’s story vanished by the light of my looking, and I awaken behind the wheel to find myself still pledged to the present, my skin in the sharpest touches returned to me, my body becoming real as birth as I remember which of us lives above the hungering ground — it is the common contract between the dead and the mourner that the former will tend to all

1 the madison review

the tedious phantom work, appearing almost palpable for a time until some healing brings abandonment,

but look how long I have hauled you, little boy, afraid of letting time termite your face, look how I learned to rend my body down the middle

to be in two times at once, a hybrid thing divided into now and then — how easy it is, how easy it is to recall the script of dead years, dog-eared and rehearsed so often that one learns to reverse a haunting — by now I know you must be weary

of my visits, having to always be ready for the scene, in position to lip-sync or snigger, cartwheel or quiver at the mongrel, when you’d rather rot, rather play along the bays

beyond my memory, your unfading cage.

Poor handsome boy, collecting shells on the beach behind our old bedroom — I know you suffer me, glancing back over a sharp shoulder, as though you sense my look still hooking your life.

If you could see me, really, a man-wraith walking backward, you would read the sorry salting on my lips, my mouth a hollow refusing to be filled with any word of farewell.

2 the madison review

3 the madison review

Tournament Time

Georgio Russell

Niagara, and a blond head hollers nigger above the blade of his down-rolled window,

and the tall teen boys on my ball team abuzz now in the busy Tim Hortons lot, cursing

at the whip’s deaf metal, his silver Honda joining a main road after the drive-by jeer, and our Polish coach grows ruddy like we would if our pigment permitted, and Rav’s fist furls

although he is Sikh and says that his turban’s a type of durag, then some older women in wool

with coffee walk over to console us, and soon the slurs of our upbringing are summoned and weighed, and a third of my teammates confessing they were virgins to such words, and the rest regaling the group about their first and worst times, and me, the small-island

migrant, seething but keeping my fire quiet, and nothing to be done but sip on bitter tea, and coach whose grans were called ‘kike’ cries inside a toilet stall, and the weekend misleading with its goose song and snowmelt, and the sunshine suggesting it should be warmer by now, and the criminal chill of this country still fingering through our purple tracksuits,

4 the madison review

and later today the last game screeching on and on and on, and the whistles for once working in our tired favour

5 the madison review

A for AVA

Georgio Russell

The little girl I tutor each evening frees herself from the kitchen table, where she leaves a paper apple, colored as if with claws, to crawl again into the only cubby square without a tupperware’s worth of school tools inside, and I corral her fetal body, father it back then tuck her seat beside me so she can finish off the fruit her fingers insisted must be indigo, like the avocado she once called “Ava” wore the hue of mud plus the smudges of her sobbing, like her sun in yesterday’s session shone its circular purple upon a zoo of gleeful people she had gifted motley skins — she is moving the crayon slowly and almost too soft to stain the picture on top of the page on which she is done struggling to write her rows of capital A, each rickety pyramid drawn at first over a dotted template before these vanished and she was made to form the letter all her own — in three weeks she might have yielded an equal amount of words not counting her own first name, otherwise a vow of silence I hear some other children have teased as real meanness: silly child who never speaks, mum girl so given to grunting and the sudden tantrum, whose Ziploc snacks those students stole because they know she’d never tattle, withholding her voice even against the cruelties that call her hunger forth — when we get to B, she refuses the symmetry problem some letters pose. I erase wherever she scrawls the symbol in reverse, and she covers her ears to the noise of my correction, flips the page back to A again and again, palming the pencil with a fully squared fist, steadfast in her faint making of bodies that do not change from weird to worthy depending on their pivot, tracing and tracing her first-lettered proof of personhood.

6 the madison review

At pick-up time, her father will pet her plaited black hair and joke about her book of alphabet rebellion, consonants and vowels streaming language back to its klutzy start — this will be a pining to hear of progress — he will want to know that, one day, his daughter will shake this delay, able at last to lead him with her words toward what hurts, recite what has been stolen, that this small love who leaps when the doorbell conjures him has not been doomed a dizzy life — he pays me not just to pry her sound but to stop the otherness tumoring rapid, and I will praise, in spite of gibberish, that she will always know her own name.

7 the madison review

Peacock

Audrey Toth

The peacock has a name— the first sign that we have all become too involved. Sometimes I side with my boyfriend, Ben, a supporter of the “Let Percy Be” side on Nextdoor. He moved into our house in the desert a month before me and explained what he had learned from the mailman: Percy, a mascot of sorts, has been around for at least five years, half the life of Vivienda. But one resident who used to work at a zoo (“supposedly,” Ben added) keeps arguing that he should be rehomed to the park a few miles away where he probably came from, or to a zoo.

The Percy drama unfolds over the app, where everyone is a peacock expert. Although I have heard it is an app for racists and bored, paranoid suburbanites, I am bored myself so give in. I see that Ben has written, “This is the only home Percy knows. Let him be!”

His primal scream, loudest in the mornings, is what flips me. Someone has written, “I have witnessed peacocks in the wild— their hoots are not as sad as Percy’s.”

“I hear it too,” I write back. “The sadness.”

Ben picks me up from a visit to the optometrist. I was hesitant to find one here as it would signify a real commitment— a burrowing in, like a foot sinking into wet sand on a shoreline. My dilated pupils ache. Ben leads me by the hand to his electric car, sleek like an enamel soup ladle, and we glide away, the inside quiet as the center of a cloud.

Ben bought the house before the first pour of concrete went in. From afar he decided on minor variations in window height and square footage distribution amongst the bedrooms. I was consulted so that I could “see myself” in the details. In the quietest hours of the night, I questioned my call of Nairobi Blue bathroom tile or open kitchen shelving, until eventually all the choices we had made began to dictate the choices that piled up before us; the colors and widths and styles funneled into a category (“modern-bohemian”), and became our inevitability, our fate.

8 the madison review

Ben would visit the construction site and send me photos. I’m building you a breakfast nook! A great and rare gesture of love, I felt, to have someone build something just for me, no matter that he hadn’t been allowed to lift a hammer himself. But he did, in fact, own tools, could fix cars and appliances, which gave him an outdated but appealing sexiness. I thought about his sexy qualities a lot, tallying them like my collection of freshwater pearls. They comforted me when I admitted to myself that innate markers of attraction were absent, had never been there to begin with— the soft weakness that should have fluttered through me when hit with his scent, concentrated behind his ears, in the curve of his collarbones.

The house is on the outskirts of Vivienda, which has grown like a patch of fungi, creeping outwards in all directions. In the center are the people who have been there the longest. I thought they’d be hostile to newcomers, who are suffocating them geographically, but they begin reaching out right away. Ben accepts an invitation to a one-year-old’s birthday party. “Come on, Alex. It’s mostly for the adults,” he says, repeating the mom’s pitch.

“There’s something for everyone out here,” says a dad as he sets his baby down with the other babies, who don’t know they are there to celebrate the birthday girl, solemn in her tiara. They are corralled on shady AstroTurf by a plastic fence and have their own music— sparkly, paired-down renditions of 60s classics, The Beatles and Sonny and Cher , which clashes with the music for the adults, abrasive Top 40 from a few years back. Mist puffs from the awning of the house, which is painted the same sandy-pink as ours. The houses are meant to blend in with the natural landscape, to try to seem like they too have existed for billions of years.

“We’re adventure junkies,” Ben tells the dad. He had described himself as such on the dating app where we had met, beneath a photo of him flying through the air on a dirt bike. For our first date he had taken me backpacking. He stuffed many more pieces of gear and gadgets than could seemingly fit into his pack, like Mary Poppins. I swam in lakes, tanned my whole body, shed three pounds. Soon I forgot what day it was, which brought me peace. How many times had I thought about camping, as something I would do one day? I liked being with a person who followed-through.

The dad laughs, gestures to the sun. “Unfortunately, you’ve missed your window. There’s an indoor driving range though, all digital.

9 the madison review

Great AC.”

Ben looks disappointed. Many unofficial great wonders of the world lay less than a day’s drive away, but, as it turns out, they are untouchable, the heat too dangerous.

Just as we’re about to sing to the birthday girl, I sense a shadow. The peacock, his iridescent plumage on display, is perched on a bolder that edges the yard. The guests quiet down and take out their phones. As they creep closer, our hostess hisses, “Don’t scare him off!”

An elderly man says to the birthday girl, “It’s a sign of good luck that Percy is visiting you on your birthday!”

Everyone is enchanted. But when a kid gets too close, Percy deflates and hops over the fence. A few people clap, including Ben.

After cake I pull Ben away. Cars are piled in the driveway, along the curb; everyone drove, though you can cross the development on foot in fifteen minutes. We consider ourselves noble as we travel from the shade of one Palo Verde tree to the next.

Scrolling in bed that night, I see dozens of photos of Percy from different angles at the party, people commenting on his beauty, on the serendipity of his presence. “Should have given Percy a beer!” someone has written. “Percy loves to party!”

A man named Daryl has written, though, that Percy might have been drawn to the party for the food, and that he’d heard, too, that some people were leaving meat out for him in bowls, as if he were a stray cat. “I have to strongly urge against this. Feeding him only increases his dependence on humans. He could lose the instinct to forage for himself.” People have replied with gifs of eye-rolls and retorts that Daryl is “too negative.”

“Are you seeing these comments?” Ben says. He’s wearing his new reading glasses. He’s a few years older than me, and each misalignment of shared collective history unsettles me. He had been too old for Beanie Babies, couldn’t understand the thrill of saving up to buy Patti the Platypus. In turn, I can’t stand his nostalgia for grunge music.

“Who’s Daryl?” I ask.

“The zoo guy.”

I roll over. “So maybe he knows what he’s talking about.”

“He never said he was, like, a zoologist. He could have been the guy

10 the madison review

who cleans up after the elephants.”

He has a point, but a few minutes later we hear Percy’s call and Ben perks up, smiling. How can he not hear the longing in his voice?

Ben moves a tree, a Brisbane box, from one side of the yard to the other. Almost immediately it looks dead, its leaves crumpled and colorless as sand. “It’s only in shock,” he says, eyeing me. “Give it time to adjust.”

Growing up, I had read and reread a book of interviews with patients in palliative care, which sat on a shelf in my family bathroom, the pages warped by years of shower steam. One woman advised to choose a life partner who would offer you an interesting life and expand your horizons, that that was more important than passion, because passion always dies. Others said that love alone was the most important factor in a marriage. When my parents divorced and my father moved out of the house, my mother purged everything, the stack of books and magazines in the bathroom included. Recently I asked her if she remembered the book, and she said she did. Only one piece of advice had stuck with her: take care of your teeth.

I was able to keep my job as an assistant to a talent agent on Broadway. “No one really needs to see you in person,” my boss told me when I broke the news to her. Ben encouraged me to quit, to take some time to figure things out, but I couldn’t spend his money. I felt like I had already taken something irreplaceable from him, like his kidney, before I’d even stepped off the plane.

Ben is a biomedical scientist with a background in computer science. His life goal is to create a program that can test the effects of medications on human cells to avoid having to use lab rats, because he is a vegetarian who cares about all living things, even at thirty-eight when most people have become too worn down to follow ideals that compromise their enjoyment of life.

Ben buys a book: A Method Book for the Development of Complete Independence on the Drum Set . Then he buys a drum set off Craigslist. It’s rusted and covered in stickers, but “a good place to start,” he says. “It’s important to be a lifelong learner.” He can play a decent beat within

11 the madison review

an hour. And I know he’ll stick with it too. His boss had suggested he learn a few phrases in French so he could communicate with his counterparts at the Sorbonne, and he made it to all the way to French 3. I haven’t learned anything new lately, and I know this bothers Ben. “You would be good at rock climbing,” he urges, adding, seriously, “With those legs.” To be fair, I argue, my whole life is new. Until a month ago, I had never been to the southwest. I couldn’t believe a place so blisteringly hot and dry could sustain human life, but this planet belongs to humans now, of course. We can live anywhere. We evolved to walk in order to decrease the surface area hit directly by the sun, and we’ll continue to evolve. Some scientists argue that the new geological epoch, the age of humans (officially: Anthropocene), began in the 1950s, when radioactive material from nuclear fallout made its way into the roots of the earth— the rocks and ice and mud that formed the planet. We have added enough to the record, they say.

We drive out of the development and look at the stars through the filter of an app, lines connecting the constellations for us. Ben reads, stumbling over the Greek: Aries is the mythical winged ram with golden fleece that was sent by a nymph to save her son Phrixus after his father had been given false prophecy that he had to sacrifice his son to ward off famine. In the myth, Phrixus and his sister Helle climbed on the ram and were carried toward Colchis on the shore of the Black Sea. Helle lost her grip and fell into the sea on the way.

“Just look,” I say, pressing his hand down to his side.

“It’s better if you know what it all means.”

I take his hand and tell him that the world would be a different place if everyone could see the stars every night. Just the stars, with their naked eyes. As he tells me I’m right and kisses me as I realize I stole the line from Twitter. He latches onto me like that photo of Yoko and John, and I begin to sweat. I’m supposed to be happy, the whole thing is so romantic. But now I’m thinking about Helle falling into the sea. When Ben begins to breath heavily, I unlock his screen with his face and continue reading. It turns out she had either drowned or was rescued by Poseidon and turned into a sea-goddess. Well, which was it?

On the app, Daryl continues to chastise “certain individuals” whom he has seen carrying bags of chicken feed from their cars around to the backs of their houses. “I know what you’re doing with that.”

“Maybe we should start feeding him too,” Ben says.

12 the madison review

“Daryl says not to.”

“He’s already dependent on humans, so now we have a responsibility to feed him,” he says, using Daryl’s earlier warning as justification.

“He says, too, that peacocks will tear up your yard.” Ben ignores this.

A single woman living in a four-bedroom house on our block is one of the feeders. She’s always bragging about how much time Percy spends in her yard, saying she feels “blessed.” Ben wants to bring us good fortune, too, but I don’t think it counts if you lure him. He has to come to us on his own.

In a dream, Percy appears at the foot of our bed, a dead fish in his mouth. Then we take him on a road trip and he keeps trying to fly out of the sunroof. At a rest stop, he pecks the eyes from a child. I have heard that dreams are your brain generating random scenarios and working through them so that it will be prepared in real life should they ever come to pass. I find this endeavor of the brain sweet and earnest. If I ever see Percy look at a child the wrong way, I’ll know what to do.

At another birthday party Ben meets a guy named Scott who has heard him playing drums while walking his dog by the house, and he wonders if Ben might like to “jam” with him. Scott has a faux-hawk and wears leather bracelets and talked too loudly, but I’m glad to see Ben making a friend. If I leave, at least he’ll have Scott.

I drink a low-calorie hard seltzer called Misty and watch the kids going wild in the combination bounce-house-water slide while I hover near the women, who are discussing the best lubricant to use for conception. Ben and Scott jog boyishly up to me and Ben asks if he can go to Scott’s to check out his setup. He’s always asking me for permission. “ You say you want your freedom/ Well, who am I to keep you down? ” I sing off-key, sarcastic. I have had too much Misty.

He gives Scott a nervous laugh, then leans down and says in my ear, “I was just trying to be nice.”

The moms ask me if Ben and I are planning to get married. I tell them about how I used to think I had a feast of routes before me, and how suddenly they seemed to close one by one. When Ben bought me a ticket out West— a phrase like from an old movie I’d roll around in my mouth— I realized that this might be the only route that stayed

13 the madison review

open. We hadn’t even been living together in New York, but here our mail would sit side by side in a metal box posted into the ground. They say you’re supposed to find yourself before you pair up, but I was hoping it would work the other way around for me, I explain. The women look embarrassed. I drop the can of Misty to my side.

On the walk home, I pass by a garage sale. The owners of the junk— appliances layered with sticky film, rococo mirrors, glass blown lamps— wave to me from the porch where they sit beneath misters. A guy in a fishing vest, its many pockets stuffed, is using a wood-handled gardening shovel to sift through a box of hardware, the metal too hot to touch. “People used to fix things,” he says. “Now they just throw them out and buy new things.”

I drink a glass of too-sweet wine with Scott’s wife, Jessica, at their kitchen island while “the boys,” as she calls them, “do their thing” in the sound-proofed garage. Her twin daughters are asleep upstairs. The air conditioner funnels towards me, drying my eyes.

“Scott was wild when I first met him,” she tells me. “Absolutely feral.”

I laugh but worry that Ben sees me in a similar light. He’s always asking me if I have things and looks surprised when I say no; no tennis racket, no cramp-ons for snow hiking. The same for when I don’t know how to do things, like change a tire. But he is also eager to give, to teach. He is never patronizing. He only wants me to enjoy life as much as he does. Though once, when he grew visibly disappointed to discover I couldn’t read music, not even on an elementary level, a “skill everyone should have,” I’d snapped and told him what I’d heard from a French girl when I studied abroad in college: Americans have an obsession with hobbies, with bettering themselves. What’s wrong with just living?

“Now he alphabetizes our spices,” says Jessica, pulling out a drawer to show me. She pours me another glass and asks me if I want kids. “Me?” I don’t think I’m old enough to be a mother, I want to tell her, but of course I am plenty old.

I drive into the desert expanse alone, lay a wool blanket on the flattest boulder I can find. I feel like something is out there in the blank nothingness, watching me, but I step through the fear, breathe, turn my attention upwards and let the stars form shapes in my mind.

14 the madison review

I see a donut, the Statue of Liberty, not the shapes the ancient people named. Of course, they only saw in the sky what they saw in their own world, a reflection, like a pool of water hanging above their heads.

“Percy is doing the mating call to me,” someone writes on the app. “I just love him so much.”

Daryl has had enough. He pastes links to articles about how peacocks are not domesticated animals. “Any sense of companionship is all in your head.”

Daryl has a small cast of supporters. I “like” one of his posts, looking behind my shoulder as if Ben is watching me.

Percy’s fans double down. They report sightings of him as if he’s Santa Claus. Someone creates a map of Percy sightings to try to detect a pattern of behavior. Ben bought the chicken feed a week ago but so far we haven’t been visited. He stands at the window with his arms crossed, surveying the yard, jolting at any perceived movement.

Daryl sends me a private message letting me know that, “A few of us want to do something about the situation.” Would I be interested in “taking next steps?” From somewhere inside of me, a leader rises up. I tell him to tell the group to meet on Thursday at the quietest Starbucks in town, the one next to a defunct Bed Bath and Beyond.

One night Ben doesn’t come home for dinner, but it’s not band practice night. No text. I feel relieved. In bed, I watch a show about people who work on yachts and the drama that unfolds out of sight of the people they serve, though sometimes it erupts and spills over; a fourth cousin of the royal family will get into a fist fight with a bartender for flirting with his girlfriend. After midnight I hear Ben come home, the back door slides open. I look out the window and see him in the yard, peering at the bowl of untouched chicken feed.

I meet him in the kitchen and offer him the leftover pasta I made. He takes down a glass and holds it up to the light, wipes it with a dishtowel. Then he does the same with another glass. “Why aren’t you asking me where I was?”

“Why are you waiting for me to ask? Why don’t you just tell me?” He returns the glass and doesn’t answer. But then, in bed, he lays on top of me with all his weight and asks me if I want to drive to the Grand Canyon, or maybe Lake Havasu, or both. There’s also Joshua Tree. Whatever I want.

15 the madison review

Grand Canyon, or maybe Lake Havasu, or both. There’s also Joshua Tree. Whatever I want.

I fall asleep hopeful that everything I admire about Ben will morph into a feeling of love. It will be like baking a cake— as long I have all the ingredients, I’ll end up with a complete and delicious product.

On Thursday, I work from the Starbucks, so I’ll be ready for the meeting. As I’m finishing up, I notice a guy watching me from across the room. At exactly three, our meeting time, he comes over and sets his black coffee on my table. “Alex?” he says. A large silver cross hangs from his neck.

Hi,” I say, closing my computer. I realize it’s the guy from the garage sale. “How did you know it was me?” But he doesn’t have to answer because when I look around I see that the place is empty.

“Where are the others?” I ask.

He shrugs. “It’s easy to say things from behind a screen. Harder to take action in the real world.”

I nod, looking at my own screen. I feel weird scheming alone with Daryl.

“You said you’d be free at three.”

“I am.”

“What are you up to on that thing?”

I close the screen. “I work for a talent agent. On Broadway.” I explain that most of my job is translating casting directors’ rejections and disinterest into palatable justifications. “I was just telling this kid, he’s like eighteen, that the reason we can’t get him an audition for Beetlejuice is that he’s too sunny, too innocent. Book of Mormon would be a better fit. You have to make sure they leave the meeting believing there’s nothing wrong with them.”

“Does it work, do they believe you?”

“They always act like they do.”

“They don’t want you to know they’re hurting.” He closes his eyes and sips his coffee. I have one of those drinks that looks like tiramisu, and my plastic cup towers, sweating, above his.

“So, what do you want to do about Percy?” I ask.

“I used to be a vet tech at a zoo in Dallas. One of my jobs was microchipping the animals.” Daryl takes out his phone and opens Maps. There’s a blinking red dot on the west side of the development.

“That’s him?”

16 the madison review

“He always sleeps in one of three locations.”

“A routine.”

Daryl nods, zooms in and points to three red flags. Then he shows me a photo of a cage in the back of his 4Runner.

“Sounds like you’ve got it all figured out.”

“I can do it alone, but it would be easier with some help. Will you be my lookout?”

The employees begin to silently execute their closing duties. “Why are you so sure Percy wants to get out?”

“Because he’s nearly filled the measure of his creation.”

“What?”

“Another job I had was putting animals down. They live a long time in the zoo, so I only had to do it a few times. But I know an old bird when I see one.”

“You’re going to kill Percy?”

“Of course not. I just want to give him a nice place to rest.”

Things have been tense lately, but IKEA lifts us up. We buy more furniture, a cheap rough rug to go beneath Ben’s drum set. As a team, we follow the directions for assembly. The new additions excite Ben. Next time he wants to get some gardening beds; he’s always wanted to grow his own food. I feel comfort in knowing a tomorrow is waiting for me here, a tomorrow with detail and certainty, if I want it.

I spin around in the new office chair and check the app. Someone has posted a photo of Percy eating bird seed from an open palm. I think about what Percy’s measure of creation might be. Maybe it is, in fact, to bring joy to the people of Vivienda.

On the other hand, he is a social animal, meant to coexist with other peacocks. Not to mention, cement can reach one hundred and eighty degrees in the sun. This is no place for a bird that primarily walks.

The plan is: after Ben leaves for band practice on Tuesday evening, Daryl will send me Percy’s location. Once I arrive, Daryl will lure Percy into the cage using a recorded call of a Peahen and a bowl of nice juicy worms while I stand by and keep watch.

After Ben heads out I dress in all black, feeling like a ninja, excited for the first time in a long time. I go to lock the back door but catch a wave of movement out of the corner of my eye. I open the door and turn on the light, startling Percy, who rustles his tail, then freezes.

17 the madison review

Slowly, I pull my phone from my pocket and see that Daryl has texted: PERCY IS AT YOUR HOUSE. STAY THERE.

Percy relaxes and goes back to pecking at the grass. He’s getting used to people. He circles the yard, then I follow him as he makes his way down the side of the house, pausing to smell the jasmine that climbs up the fence. I can’t help believing that his presence is a sign of good fortune. Our house is not one of his usual spots. Maybe he’s here to tell me that he wants to stay in Vivienda and that he wants me to stay too, to keep trying.

Percy investigates our front yard. A minute later, Daryl pulls up. He looks at me and puts his index finger to his lips, opens the back of his car, then turns on the peahen call, a two-note honking that is hard to imagine is attractive. Percy stands at attention, his neck lengthening and shimmering under the streetlight.

“Wait,” I tell Daryl. “Is this illegal?”

He shakes his head, shushes me.

Then I hear yapping and see two figures walking down the sidewalk, a small dog off-leash at their feet. When they cross beneath the white light of the streetlamp, I see that it’s Scott and Jessica, a baby monitor in her hand emitting the sound of rushing water. I’m confused. Is Ben hurt? Is he with another woman? Where is my predictable boyfriend, the man who is teaching me to drive stick shift on his prized vintage BMW, despite the damage I inflict on it with my clumsiness?

“It’s Percy!” Jessica says, squatting to calm the dog. Daryl shoots me a look that says get rid of them. They come to me, waving hello. I’m overheating in my ninja outfit. “We don’t want to scare him off,” I whisper.

“Let me just get a picture,” Jessica says, pulling out her phone.

Daryl turns up the peahen sound and it works— Percy bobs over to the car as if pulled by invisible strings. Scott says, “Oh my god, are you trying to capture him?”

“Just stay out of the way,” Daryl says, circling behind Percy as he hops by his own free will into the cage. Daryl swings the cage door shut. Jessica gasps and cries out, “I’m filming all of this! I’m posting it now!”

“Daryl,” I say, thinking of Ben, wherever he is, watching me on the video. “We don’t have to do this.”

“It’s already done.”

I grasp the metal of the cage and watch Percy, oblivious to his

18 the madison review

confinement, enjoying the worms.

Scott and Jessica look angrily at me. But I’m on their side now, the side of the good people of Vivienda, my community. Most importantly, I’m on Ben’s side. Where is he? Daryl is standing arms akimbo, smug. I reach out and fiddle with the latch; he sees what I’m doing and swipes my hand away, but I reach out again and release the door. Only Percy doesn’t seem to notice. “Come on!” Scott shouts and claps, urging him, but Percy stays put, content. Daryl lunges and shuts the cage, hops in the car and drives away, the call of the peahen fading until it disappears.

In the morning, I find a movie ticket stub in Ben’s pocket. Everything Everywhere all at Once. He has been hiding out in the dark, looking for ways to protect himself from me. Maybe he’s already gone, in a way. I crawl on top of him. “You’re hurting me,” he says. He slides away, but I burrow into his armpit. Have I ever told him about my time in Indian Princesses? It was so strange. He says he doesn’t know what that is. He was probably too old. I explain anyway about the now defunct politically incorrect father-daughter organization. My father was Big Hawk, I, Little Hawk. I sang the chants with abandon, raspy voiced by the end of our lively meetings during which we crafted miniature drums from faux-suede, coin pouches with beaded ties. I was part of a tribe. Each year we received a new colored feather at a formal ceremony, handed to us by a white man in a costumey headdress. I can’t remember how it all ended, I tell Ben, but I don’t think I ever made it to the final year, to the black raven’s feather that signified you had made it to the top of the Princesses, but also to the end.

19 the madison review

SUMMER / STOMACH / SICKNESS

Allison Flory

The boys are playing killing games again, holding each other underwater and trying to swim.

It’s late July and I’m still tonguing the aftertaste of sulfur like popsicle juice.

Next summer the boys will try to take my clothes off and I’ll be aware

of the body that sweats beneath them; next summer I’ll be more than a girl

that watches bad things happen and wonders why I can’t be a part of them.

A girl is meant to object to violence while stepping into it with small bare feet

and next summer, when the killing game is hunting me

I’ll pretend the sulfur in my mouth’s disgusting.

20 the madison review

21 the madison review

24 the madison review

the madison review

THERE IS A WAY TO COMMUNE WITH ROADKILL.

Allison Flory

I used to call myself an empath for shivering every time I drove past gutsmash on the road

my longest friendships are with the girls who held my hair in the bathroom vomit on my lips else it’d be my hair on my lips dog hair keeps pilling when we kiss too long

days without showers: it’s winter too long before it’s spring

freeze pales gooseflesh skin til it’s phantom colored moth colored

I used to smoke til I was nauseous and fuzzy along all of my edges still found a way to be sharp all the time

I used to call myself an empath for shivering every time I drove past gutsmash on the road but really it was just gross: the way insides keep coming out and making a mess and smearing my tires and smearing my lip stain on your chin friends and hair

I’m smearing bile on the back of my hand again

26 the madison review

27 the madison review

Whole

Daniel Ooi

For the photograph of Kyu Song Cho, Cindy Cho, William Cho, and James Cho in the news story, “6-year-old boy is lone survivor of family in Texas mass shooting,” on May 9, 2023.

I.

In the daylight, the stars are still collapsing, they have had enough. In May we gather for another reunion meal, swallowing bullets with our bellies, angry made-in-America bullets. I hear my mother teaching me to stomach every last grain of rice. If not , she warns, every pellet left becomes a hole in the face of one you love. Tell me, mother, how much more must I eat before I too am made-in-America.

II.

When you first learn how a bullet carves a path through all these sun-kissed rooms walls of plaster walls of polyester shirts walls of skin spiraling everything into its vortex you marvel at the entry wound crown of thorns trying to decide between the metaphor of spiral galaxy or bird’s nest

III.

In the aftermath, our family pours texts asking after my eldest brother who bought running shoes from that same mall a week ago. We stumble across the photo of your whole family so close to laughter in black and white sweaters. And in your father’s square glasses, his toothed smile, I see my eldest brother, holding a son he could never bring himself

28 the madison review

to bring into the world, all these too many possibilities.

And you, arm raised, eyes smiled shut into tight lines, as if you could hardly stand all the light this world promised.

IV.

When I was six, my biggest worry was if she liked me back, the church girl with the longest black hair. I stole glances at the back of her head, while learning Christ would come again—dreamt of God stealing my whole family away like a thief in the night.

When you are six with a hole gouged in you, what do you dream of?

In your sleep, you look through a bullet hole, wide as the marks in Christ’s hands. At first you see what looks like eternity’s embrace, but reaching the end of the infinite corridor, you find only your self standing in the eye of an entry wound, looking around, not quite sure who is the hole, you or your family.

V.

The night I found God’s room empty, I learned soon after everything was made of holes,

everything we have words for, everything we do not, so much longing to be filled, the impassable distance

between every molecule. At the core of each body lies a center of gravity. In human bodies it is the navel, a chalice .22 in diameter.

VI.

I want to shield your ears from the prayers of those old church ladies, their thoughts that this too is a blessing. That your life is a miracle.

Still tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow, you will wake up, eyelids breathing in the windows, hungry for the morning, and maybe that enough is miracle.

29 the madison review

VII.

By now they will have power washed the clinging memories, dark brown caked in cobblestone, into the storm drains, swirling down—the way one pulls the stopper from a bath.

When I was six, it brought me great joy to watch this tiny whirlpool, a hole thirsting for water, shape of the wailing mouth, the wordless open mouth, the fish mouth looking up from my father’s bowl.

It leaves behind a ring of debris, like the halo left by your mother’s coffee cup, clinging hazel, almost invisible in the kitchen light, etched into the countertop.

30 the madison review

31 the madison review

Brunch with Phoebe

Chloe Cook

The hollandaise is a bit sour, the biscuits dry. What of the rugby team that crashed into the Andes and resorted to cannibalism? They’d tried eating leather strips torn from luggage, cotton pulled from seat-padding. I would’ve made shapes in the snow with my piss stream a la Warhol. Making art has been a human instinct for centuries: recall the bone carvings found at that dig site in Germany—the ones resembling Challah loaves—or the three wild pigs painted on a limestone cave in Sulawesi. Some facts are just facts: ham is the superior Thanksgiving protein, people who whistle or hum in crowded check-out lines should choke on tar, sometimes you have to chew human flesh to survive. Did I hear about the mom who’s going to jail because her kid died in a hot car? No, but, frankly, so much else concerns me: beads of rain gliding down the car window begging me to lick them up, cursive monogram stickers

32 the madison review

on Hydroflasks and Macbooks, blackened grouper with berry slaw. Phoebe, you’ve got to live a little— the secret to having a good “aura” is not studying Philosophy in college.

33 the madison review

Patagium: Having left the Yurt for Gotham City

Miriam Akervall

You send a picture of the Bat Cave It looks the same crisscross

lattice christmas lights bright clean stripes behind the stringers where the canvas was pulled over to close a hole Except now dome framed by a dozen little bottles suspended

wearing wings Tequila-bat whiskey-bat some-sort-of-can-bat blurred

out of focus You took it from the bed I drilled brackets into after someone

else fucked it loose

Where we wedged our rest together masks

on content with the dark Now I lay in bed surrounded by glass

Joe Chill in 5B parties all night and smokes on the sidewalk scot-free My mom doesn’t ask about you having no word for two layers of skin so thin it will make you float

34 the madison review

35 the madison review

Wave pool: after antipsychotics

Miriam Akervall

In the same way you tell a boil by the sudden quiet, the way the steam drops in pitch, so you watch for one thing to become another, catch the coffee before it announces itself. You remember the public pool, how they blew the whistle when the waves began, how familiar it felt to feel the ground tilt.

Who can say if the absence of a sound is the same as tuning one out.

Now it is the body on a chain listening to the foghorn of its blood. All day you work to keep your jaw cinched to your skull. A bad belt you keep adjusting while meadowlarks wrestle earthworms from the lawn. After a long time at sea, there is a sickness that makes legs question the ground. Nobody really knows what’s rocking.

36 the madison review

37 the madison review

Capt. Hezekiah Coffin

Jared Lipof

Warren’s wife’s head appeared in his office doorway. “You in the middle of something?”

He faked a yawn and opened a folder and scattered depositions on top of the Quincy’s Historical Emporium catalog he’d been examining. “I believe I’m at liberty.”

Caroline came in holding some paperwork of her own and sat in one of the two mahogany wingback chairs on the client side of his desk.

She ran a fingertip along an armrest. “When’d you get these?”

He pretended his full attention was on work. “Estate sale up in Concord. Descendants of Hutchinson himself, fallen on hard times. Got them for a song.”

Caroline tapped the papers in her hand. “I noticed a weird charge on the Visa Statement from the Holiday Inn.”

“Which one?” said Warren, though he knew exactly which one. “Fort Ticonderoga.”

Warren had taken the trip last weekend. He could feign only so much ignorance so he opted for acrimony. “Why are you micromanaging my travel arrangements?”

“I’m not micromanaging. I only logged in to see if AT&T pulled any more double-tap shenanigans.” Caroline slid the printout across his desk as if entering it into evidence. “This three hundred dollars was an incidental charged to your room for damage.”

“Damage?” She’d even used a highlighter so he couldn’t miss it. Sure enough, they’d charged him for the toilet. “No idea. Probably just a glitch. I’ll give them a call.”

“I already called them.”

Of course she did. Caroline had to iron out wrinkles on the spot. She probably suspected he’d drained the minibar and rented thirty adult movies in the forty hours he was checked in––an indictment he’d much rather build a defense around than the truth. In a display case across his office sat a bust of Cornwallis, flanked by a flintlock musket and a pewter mug from the original Green Dragon Tavern, whose total cost exceeded this damage bill by an order of magnitude.

38 the madison review

Nevertheless, Warren doubled down. “No idea what they’re––”

“The front desk attendant I spoke with––”

“Mallory?”

“ Her name you remember.”

Warren pointed to the depositions staged in disarray on his desk. “Trappings of the profession.”

“Anyway, Mallory said housekeeping found the toilet cracked into three pieces.”

“What window of opportunity exists between my checkout and housekeeping’s entrance?”

“I see you’ve cast yourself in the role of defendant.”

Warren gestured at the professional trappings.

“You’re not denying it, exactly.”

“I have neither––”

“Just tell me what’s going on?”

“Nothing. Go ahead pay them. We can afford it.”

She tapped the rest of the paperwork. “Yeah, about that.”

Caroline Coyne’s fiscal concerns were not without merit. Her specialty was corporate law––mergers, acquisitions, real estate expansions––and her fees made up the lion’s share of Coyne & Coyne’s revenue, leaving Warren free to chase down ambulances and class action suits that proved elusive for months. She’d been the breadwinner for so long he’d considered an array of options: taking on the drastically heavier workload of a public defender for the steady paycheck, accepting a former client’s offer to participate in a money laundering scheme, and hanging up his license altogether so he could flee to some tiny Midwest town where nobody knew his name and he could start fresh and almost certainly fail all over again. Back in undergrad, when his brain pinwheeled down depressive spirals he would confide in his old roommate Larry Determan. So before he resorted to crime or desertion he reached out to Larry for advice, and they met at a tavern on Beacon Street, near the gold-flaked dome of the State House.

Larry poured from a pitcher. “This guy at work goes to these oldtimey military, what, stagings . Full regalia, muskets, cannons, drums and fifes.”

“How’s that relevant?”

39 the madison review

“Dude fishes for business cards. Boosted sales by ten, twelve percent. Turns out the reenactment set’s got money to burn. Probably need legal services too.”

Warren swallowed his beer. “Sounds like a lot of work. What do you wear?”

“You can rent the costumes. Tweed or, like, wool. I’ll go if you go.”

Larry Determan, at a historical reenactment? Back in college he flipped through Sharper Image catalogs and blasted Aphex Twin CDs that sounded to Warren like a modem connecting to the internet in those innocent days of dial-up. Now an investment analyst at John Hancock, Larry seemed like the last person who’d be interested in nostalgic make-believe.

“There’s one next weekend,” said Larry. “ Shot heard ‘round the world .”

Warren met Larry at sunrise on Lexington Green, knowing it would be a waste of a day. The British soldiers gathered at the far end of the field in their unblemished crimson uniforms and shining weapons and clinking accessories. Warren and Larry assembled with the ragtag rebels, bearing rickety muskets and looking more like farmhands than any kind of organized military. They were going to get demolished. Warren tugged on his rented tri-corner hat and cinched his twine belt. The wool breeches chafed his inner thighs. Later, he would learn that many recreationalists wore spandex athletic gear to prevent such friction, but by that point Warren considered it cheating and preferred discomfort over anachronism. There was no point in doing this if you weren’t going to do it honestly.

Major John Pitcairn fired the eponymous shot and gunfire exploded from all directions. The blank cartridges sounded authentic in the fog-laden morning. Alongside his fellow Americans Warren advanced upon the enemy and fired some shots of his own, ducking and dodging and hollering encouragement and before he knew it, he’d timetraveled to a place he didn’t know he missed. Eventually he took a direct hit from a kneeling British redcoat and fell to the lawn, smiling at the sky, ecstatic in his own mock death. Dew-spangled grass blades arched over his eyeballs, refracting sunbeams pure and unspoiled by the burnt fossil fuels of men. He’d shrugged off the modern straitjacket of emails and software upgrades and Roth IRAs and escaped to a tranquil freedom that he could only describe as home . Bootfalls and

40 the madison review

gunshots thundered all around. The revolution would go on without him, this time. But Warren immediately saw the trick: he could resurrect and reinvent himself in time for the next one.

It never had to end.

On Lexington Green he forgot about the failures that awaited him at Coyne & Coyne but back at their cars, a dread descended upon him like the Sunday evenings of youth, weekend over, school the next day. Freedom coming to an end.

Larry reached into a haversack of coarse gray linen and withdrew a stack of business cards and fanned them out magician-style. “Thirteen, baby. How’d you do?”

Warren had gotten so caught up that he’d forgotten the entire reason for coming. “Not bad. So, when’s the next one?”

Larry yawned. “Got Sox tickets for next weekend, then we’re flying down to Boca to visit Sharon’s folks, so…”

Warren hid his disappointment. “Sure.”

“Good time, though.” Larry shook his hand and slap-hugged him with the other arm and drove off in his BMW 7-series, invisible behind tinted glass.

Warren had left his phone in the car and when he retrieved it from the console there was a text from Caroline:

hope you had fun. what time you home?

He recognized a jab when he saw one. The breezy––and frankly condescending––all-lowercase tone implied that there were many more profitable ways to spend his time, so he began to compose a reply that was just as breezy, assuring her he’d collected a baker’s dozen of business cards, that he’d been out here networking, after all. He was wondering if he should swing by the office to collect some cards from his Rolodex, in case Caroline fact-checked this claim back at the house, when the man who’d portrayed Major John Pitcairn strolled up and extended a hand.

“Thanks for coming out. Matt Abel.”

“We the people,” said Warren. “Have indeed formed a more perfect union.”

Abel frowned. “Preamble’s not presented until 1787, if memory serves. Good try, though. Kind of pluck we need around here.” He passed him a card with Dawn’s Early Light Reenactment Society

41 the madison review

printed in Caslon Swash Italic. “We’d be glad to have you.”

Abel winked and drove off and left Warren with a bona fide business card and a new sense of spiritual belonging. Then he replied to Caroline’s text.

In the year-plus since last April’s Lexington event, Warren had dropped $49,851.77 on costumes, vintage firearms and swords, leather-bound military accounts, membership dues, registration fees, and hotel rooms––for early morning events held outside a reasonable driving radius––a sum he was painfully aware of, whose paper trail had been dispersed over three different credit cards and by using his debit card’s cash-back option that seemed perfectly designed for the camouflage of expenses. He’d portrayed many characters since the nameless minuteman at Lexington, men like John Parker and John Endicott and Ethan Allen, each of which required new wardrobes, top to bottom, purchased now instead of rented. He performed extensive research, often concealing an encyclopedia inside a book of statutes to throw Caroline and Abigail––the administrative assistant they shared at the firm––off the scent of his obsession. Warren’s professional life had devolved into that of a twelve-year-old hiding a Mad magazine inside a textbook to fly under the teacher’s radar.

At first, the Massachusetts-born patriot that lived inside Warren’s ribcage only sought roles in the rebellion, but Matt Abel, who turned out to be a heavy-breather in the reenactment society, offered him the part of Col. James Abercrombie in Bunker Hill’s early summer battle. Warren recoiled from the idea of playing an imperialist devil, but once he got a look at the uniform––the crimson coat’s row of sparkling brass buttons, authoritative cockades on a tri-cornered hat of deepest midnight, the white sash, and, not one but two steel rapiers held by sheaths of embroidered leather––his allegiance underwent a shift. So he secured a fourth credit card, in his name only, using the firm’s address and setting a monthly reminder in his calendar to intercept the mail every 15th, lest the statements land on Abigail’s desk and inadvertently find their way to Caroline. He used it exclusively for clothing and accessories. And weaponry. And sometimes furniture. He still booked hotels with the other cards and paid dues with checks; he knew he couldn’t hide all of it from his wife, but by revealing certain aspects of his spending he could muddy the truth’s borders the way drunks will buy seven cocktails with cash and put two on their credit

42 the madison review

card and wave the receipt around like it’s the hallmark of restraint.

At this point the charges at The Musket Ball and Paul Revere’s Ride and 1776! all but evaporated from the other three cards and Warren hoped that, from Caroline’s perspective, it would be cause for relief rather than suspicion, that his costly interest in childish games of make-believe had begun its decline. But a medical emergency forced Matt Abel to ask Warren if he could fill in as Capt. Henry Mowat in the Burning of Falmouth event and this eleventh-hour promotion, coupled with the secret credit card, unbridled his appetite and allowed it to gallop free, and pretty soon Warren had to rent a unit at Floomer’s Storage up in Hanover, into which he wheeled several rolling racks hung with a theater company’s worth of costumes and adorned its walls of corrugated sheet metal with oil paintings of Washington crossing the Delaware and the Siege of Yorktown and the place became a sort of candle-lit man-cave, which elicited the purchase of an 18th century velvet-upholstered davenport and a threepronged bronze candelabrum, upon which he balanced six-inch tapers of animal tallow, secured at further expense from the art director at the Old Sturbridge Village Museum of Living History.

Caroline slid the firm’s balance sheet across the desk and Warren assured her he’d met some very promising potential clients on the muddy fields of Ticonderoga and when she’d been placated and returned to her office, Warren called the Holiday Inn himself.

“ThankyouforcallingtheHolidayInnExpressinRutlandjustfivemilesfr omhistoric-FortTiconderogathisisMalloryspeakinghowcanIhelpyou?” said Mallory.

“My name is Warren Coyne. I stayed there last weekend?”

“Riiiight. Benedict Arnold.”

“I was Captain William Delaplace of His Majesty’s 26th Regiment.”

Gum snapped inside Mallory’s cheek. “Whatever. Your wife called.”

“Sorry about that. Hate to put you in an awkward position.”

“Me? You’re the one who beat up the bathroom.”

Here Warren regained his legal foothold. “I checked out Sunday morning, around eight. What time did housekeeping enter the room?”

“You think the toilet cracked itself?”

“My job is not to solve mysteries. Only to introduce doubt.”

“Like maybe a ghost did it?”

43 the madison review

“I’ll pay for the damage,” said Warren. “But can you transfer it to a different card.”

“Have to fill out some paperwork but, I guess.”

“Hip hip hooray,” said Warren. “The number is––”

Abigail appeared in the doorway.

Warren cupped his palm over the mouthpiece. “Good morning.”

“Judge Altman on line two.”

She usually just sent the calls to his line. She looked worried.

“When?” said Warren.

“Um, now? She said it’s about the fitness center settlement.”

Warren removed his hand and said to Mallory, “Give me two minutes.”

“Or we can just leave it on the card on file.”

“No!” said Warren and Abigail recoiled.

“Okay!” said Mallory into his ear.

Warren hung up. “Sorry about that, Abby. Please get a number and tell Judge Altman I’ll call her back.”

Early last December, Warren scored his first legal victory in months. He’d represented two hundred forty-seven plaintiffs in a class action suit against The Republic of Fitness, a chain of health clubs that raised fees without notifying its members and, once some of them found out, propped up a series of roadblocks when they tried to terminate their memberships. Given his turncoat status on the field of mock battle, it comforted Warren to represent defrauded citizens, as if in real life he was still on the right side of things. The Republic of Fitness settled for $200,000, which came out to $688.26 per plaintiff when you subtracted Warren’s 15% fee.

Unfortunately, thirty grand was just over half of Warren’s debt and would go straight into the firm’s coffers anyway. Victorious but still short of funds, he sat in his office waiting for the falling flakes outside the window to tell him what to do. Escrow , they whispered as they gathered in cottony puffs around the strung lights. Escrow? thought Warren. As in: dip into the payout? It didn’t sound like a great idea until Matt Abel called to tell him he’d nabbed the part of Hezekiah Coffin, captain of the HMS Beaver, in the upcoming Boston Tea Party event. The Coffin family had a rich history in whaling and Warren decided that what he really needed to make Hezekiah leap into three dimensions was a $1,500 vintage harpoon designed

44 the madison review

by Abraham Stagholt himself and by this point the idea of sending thirty-seven fraudulent wire transfers from the settlement escrow to a single account in a fictitious plaintiff’s name had already been ratified by a congress of Warren’s imagination. Besides, he told himself: a) it’s not like they were cancer victims who lived near a nuclear plant; they’d just been swindled out of disposable income by some blowhard jocks whose terms they agreed to beforehand and b) he would pay them back eventually, as soon as he secured another class action settlement that, he supposed, he’d be forced to dip into as well.

This all-consuming hobby––and the secret spending that accompanied it––had put a great deal of emotional space between he and Caroline. He knew it and he hated it and he felt powerless to stop it. And so instead of stopping, he set himself an arbitrary deadline: he would use the Tea Party event as a springboard to a high-profile role––Major John Pitcairn, fingers crossed––at the next Lexington event, giving his year-long binge a nice symmetrical bookend. A few more months to indulge in fantasy and then he’d be done with it for good, like getting sober just as soon as the holidays were finished.

So he bought the harpoon and the Tea Party came and went and two months later, during a February blizzard, he began receiving phone calls from plaintiffs. It turned out the income wasn’t so disposable after all. “Seven hundred bucks,” one of them said, “can buy a lotta groceries.” Warren said these things took time and some of them said they’d talked to other plaintiffs who’d already gotten their checks and Warren explained that the gumming of bureaucratic wheels often made no sense, and he hung up and hoped none of them bothered to research the intricacies of escrow law.

This tap dance bought him a few months, during which Warren was not offered the part of Major John Pitcairn but attended the event anyway, as if his failure meant he was no longer obliged to quit, and he kept right on reenacting straight through Lexington and beyond, up until he returned from Ticonderoga to his room at the Rutland Holiday Inn to find a voicemail from one of the plaintiffs. He’d left behind his phone so as not to sully his uniform’s verisimilitude. Philip Wright had indeed done the research and organized the other thirtysix plaintiffs into a sort of class class action and was threatening to call the judge and Warren knew the teetering rampart of lies would tumble down upon him any day now.

He hung up and stormed into the bathroom and kicked the toilet

45 the madison review

with an eighteen-inch wooden-soled officer’s boot and the cistern split apart, leaking water all over the floor while he stood by, helpless, until he thought to twist the valve closed, which forced him to piss in the sink for the remainder of his stay.

Warren was puzzling out his next move when Caroline returned to his office.

“What’s this about Judge Altman and the fitness payout?”

“Goddamn it, Abby!” he shouted through the doorway.

“Don’t take this out on her,” said Caroline. “I have a right to know what’s going on at my firm.”

“What’s going on at our firm is thirty thousand in fees. You’re welcome.”

“Yeah, last fiscal year. Now what’s with Altman?”

“It’s nothing. Just a misunder––”

The phone rang and Warren held up a hand answered it. It was Asa Pierpont, the owner of Paul Revere’s Ride.

“Mr. Coyne, I know you’ve been on the lookout so I wanted to let you know that I just received a Brown Bess musket.” Asa executed one of his trademark dramatic pauses. “The Long Land Pattern .”

Warren owned three Brown Besses already––Short Land, India, and Cavalry Carbine––but none of them were quite period-accurate for British colonial use in the 1770’s. Even in the crosshairs of Caroline’s interrogation, he could picture himself at June’s Battle of Monmouth event, surrounded by the envy of fellow recreationalists.

“Absolutely. Please hang on to it, Asa.” He hung up.

“What’s going on,” said Caroline.

The phone rang again like he’d conjured it. He lunged for the handset as if this time it might be the President, granting him a full pardon or, better yet, old George Washington himself phoning across two hundred years of American misadventure to whisper the secret in his ear.

“Philip Wright on line one,” said Abigail.

Facing his ire seemed preferable to that of his wife, so he took it.

“Mr. Wright, what can I do for you?”

“Look who’s finally taking phone calls!”

Warren smiled at Caroline. “Just fine, sir. And yourself?”

“Enough of the bullshit. You’re just like the rest of them. Sticking

46 the madison review

your grubby mitts in wherever you can steal an extra buck. We’re not even real people to you.”

Caroline squinted and Warren nodded. “All of that sounds fine, Mr. Wright.”

“ Fine? It’s not fine! I told the judge. You are so fucked.”

“I look forward to hearing from you,” said Warren.

He hung up and walked over to the window. Outside, Mid-May’s floral skyrockets exploded beneath sun-dappled hemlocks, the daisies and marigolds and tulips planted in the median strip of Congress Avenue. When had he last paused to take in the staggering beauty of the planet he was lucky enough to spend a few decades on? When had the perpetual charade of being Warren Coyne, Esq. strapped on the horse blinders and eclipsed everything else? The office was only on the second floor and he wondered if he’d have to dive headfirst to get the job done. And then Caroline’s hand was on his shoulder.

“What is it?” she said.

“Look, Caro, I have a…” Most folks got nostalgic for their own childhood but Warren found if you overshot it by a couple centuries, you could spend all of your time trying to recreate something you’d never seen the first time around. And by never quite satisfying the itch, you’d never have to stop scratching. He knew the word to describe what he had. But once he came clean there’d be no going back. “I have a…” What he really wanted was to go back to their first date and do the whole thing better this time around, to be the kind of man who didn’t feel kneecapped by his wife’s vocational superiority.

“Just tell me.”

“I have a––” he said, and faltered.

By now Warren was long gone, standing at the lip of the Beaver’s gangplank, his ship packed to the gunwales with the leaves of a Chinese plant. A hundred disgruntled colonists strode his way, disguised as Mohawk Indians. Their costumes were in fact costumes. Captain Coffin raised his harpoon but it was far too late. They shoved him aside and came aboard as rehearsed, like they did every year, wrapped in blankets and wielding hatchets, white faces painted with soot. Empty wooden crates would float, of course, so the reenactment’s art department filled them with sandbags instead of actual tea, and when they splashed into the harbor they sank straight to the bottom.

47 the madison review

The birds of Fire Island don’t know that the powerlines aren’t God

Daniel Brennan

but still they’re speaking every language he’s ever made for them as my body lingers like a wound on the boardwalk.

The saffron skies shake, petulant. They’re nothing but scar tissue after a night like this, a night where my lips split open below the pool’s keening surface, mouth to bare flesh, gulping in chlorinated water along with his salty pleasure.

Powerlines lean in a stupor ahead, those drunken sailors, and around me the air is filled with close-calls. Imagine me:

sure that my face is the convex mirror through which doubt and longing map their self-portraits.

Soon, the electric high that snaps like piano wire in my blood will pass and I’ll be only mortal again,

marching home, lone soldier, along the wood slats that give with a whine under hundreds of feet like mine,

seeking asylum from the drowning calm. Seeking refuge from the wind that champs its teeth across the reeds.

Above me, birds are making nests out of gold-lacquered bones, plucking my afterthoughts to construct their homes.

In these early morning agonies, the Atlantic thrusts, its brine erotic; it sings for the same God who is nowhere to be found when the dark gives way and our island rises once more from the sea.

48 the madison review

In this half-light I am a miracle; still stumbling onward, skin anointed with the hunger of men who are as lost as me.

49 the madison review

Elegy::After Ayesha

Raees

You made buildings out of nothing. Look at the palms of my hands. Do you taste the ash in this fire?

for Q

The sun hit the curls of both of our heads and you melted. I rolled my skin all day in your wax just to embody your carcass. I can’t just write one poem and call it done. I have been isolated, caged, choked, smothered and my heels lay down in watered dust. Unforked. Can I end myself in front of you and ask my last words to match your next ones? How would you greet me? Where would you greet me? I hope you greet me. I know. I have always been putting this soul into tough positions. I have writhed it out of faith to punish God only to watch Him renounce me. How my bones jolt and how my veins jump. I never enjoyed 4 AM discos. Lack of breath. Recoils. Nailing unnailing my hands, sucking off the crescents in my palms. I never enjoyed pills. Just like you. I want you to remember me like how you wanted me to remember you before you refused to show me your face before I couldn’t show you my face, before our faces were foreign to not just land but also its drench. We made something out of asking the silence and hearing the silence back. Are you confused of me? Of these words? These addresses? I made these choices by choice as if choice is of our own making. When you died, I died. Look, I have no shoulder bone, no vitamin D, no dimple, no skin. I had to bomb my buildings and take a flight back to my womb where one parent held me down and the other watered me up. Have you ever lived in a second where the half of it was spent recovering from the rest? I would never want to die as much as I want to. I stand astounded open mouthed lung agape watching each day wrinkle, spot my skin, sentence me

50 the madison review

with the task to perceive this mundane to miracle.

51 the madison review

Isolation

Ayesha Raees

I lie in a sun spot. My palm face ceiling. Asking sky: “What isn’t time?” All I have gathered in a year is a block of light in a tube of black paint with a brush that dripped into a silencing :: In this isolation, I fall towards a location where it is least lonely.

“Hi”

In New York City, I hunch over a thousand dumplings. Wait for the heavens to lip me with either snow or sunlight. I marvel. I scrutinize. I alchemize a crowd to chase a soaring dandelion across the avenues only to witness it dissipate into thousand tiny fulfillings. My wish was to keep gathering signs. My wish is to keep gathering all my life some kind of object permanence. Muji Pens. Pigeon Feathers. Blushing Maple Leaves. Take care. Home. Room. Train. Reverie. You are always on fire. Don’t drink. Glitter. Don’t smoke. Kiss instead Planet with the back of a viral hand. Cry

52 the madison review

My body is whose temple?

Pinned to a flag, memorizing words like petrichor, clinomania, supine, coaxing throat to encourage love, anthem, scene.

I am from the floor finding birds in the sky while the sky lakes in my hands.

A forecasted air constructs an architecture of motifs where everything of witness cleans a slate by burying a year with wish with flock with grief.

I was made to believe all this time, I was alone. When, all along, I was just spending time with the world.

53 the madison review

Summer Friday

Parth Raval

After work, there was a wake for our friend’s mom and a baseball game.

We went to hug him then we left. It felt wrong but you said there were other guests there to help him digest the grief and we’d had these tickets for weeks.

He wore a black suit and was quiet and kind. Our seats faced the sun but you held my hand and didn’t squint.

54 the madison review

56 the madison review

57 the madison review

58 the madison review

59 the madison review

Changing Gears

Judith Fox

Widowed, I wed again, even though I suspected the man I loved might have dementia.

Even though his olive skin flushed as his brain struggled to figure a server’s tip,

as his once-sure fingers— surgeon’s fingers, piano-playing fingers—

labored to undo the hooks of my bra, unbutton my jeans.

But I couldn’t imagine myself elsewhere, wanted to watch him daily

shave his face. Brush his sleep-tumbled hair.

When his blade slipped, I’d raise the styptic pencil, try to halt the flow.

And when he stopped driving I would take the wheel, learn to shift.

Didn’t think about potholes, buckled asphalt, black ice.

Didn’t know there could be body damage— that a brain could forget to tell a tongue to swallow, a heart to pump.

60 the madison review

Cornflower Requiem

Bill Hemmig

1979, August

It was the first time she’d worn a full-length dress on the beach. Strange thing to realize now. The linen dress in that shade of blue she loved, called cornflower blue in the crayon box, the blue of the hydrangeas blooming now and dividing the dunes from the back yard. She reasoned that the dress would weight her down sufficiently. No need for stones in the pockets like Virginia Woolf; she’d be going, not into a predictable river, but into the sea with its pull and drag.

The water was, as expected, late-summer comfortable. Comforting. But autumn was bearing down, and with it the specter of winter and its long, icy darkness. Dark now, too, no moon, no stars, no color. The tide going out which would help. She knew she would resist ultimately but not now. Wet linen clung to her ankles, her shins and calves. In the house, Evan awoke to find himself alone in the bed. There was a light under the bathroom door and he heard the toilet tank filling. He adjusted his pillows and returned unwillingly to a dream about a deepsea fishing trip that was bringing up living children. The surf came like radio waves, regular and quiet, washing from knees to ribcage.

The dark, colorless despair, misery, horror, that consumed everything, always, left nothing of any use, could never be appeased with pills, talk, rest, would be, by this, finally, stopped. And it consumed also Evan, and Tim and Lisa, and Mom and Dad, whole, and that, too, would stop. The sea purifies everything. There was a pull. It washed over her forearms, her breasts. The cornflower blue linen dress, colorless now, did its job. She wondered how Victorian women in those big woolen bathing dresses ever survived. Perhaps they never went into the water. There was a sharp pull, forward. She nearly changed her mind, and then a sharper pull, forward, and then down, and up, down, up down and down and down and down and the sea was inside her.

62 the madison review

2004, June

The kitchen review completed, Evan was grateful to move on to the back yard. He found the manner in which the realtor casually appraised it all unnerving, an assault. For his part, Cliff too was relieved to get out of the house—musty, cluttered, smelling like unlaundered socks. It would have to be edited down severely and aired out before it could be shown. This is a huge amenity, he enthused, taking in the yard.

It was bright and spacious if mostly just sand and dandelions, a wall of green, healthy shrubs fronting the vegetation-covered dunes that divided yard from beach, marsh grasses and picket fencing in need of paint marking the side property lines, a picturesquely gnarled old cedar near the porch. A stone patio and a pool would have been better, but most of the beachfront properties in this part of Long Beach Island were still of this modest and older type; no one would expect a pool. Cliff made note of the notable sounds: the distant surf, the cries of sea birds, a twittering pair of cardinals investigating a bird feeder. Are those hydrangeas fronting the dunes, he asked. I’ll bet they’re gorgeous when they’re blooming. What color?

Blue, Evan replied. Or would be. The soil is acidic here as you might imagine, good for blue. But those stopped blooming… He stopped himself, and fumbled with the buttons on his cardigan. A lot of years ago, he finished.

We won’t mention that, said Cliff. Evan wondered if the realtor knew and then decided he was referring to the reticent shrubs. But Cliff did know that the seller was avoiding talk of his wife, a suicide at forty-seven. He’d done his research, like always. No surprises, no getting blindsided by a buyer with a relative who worked for the newspaper or the coroner back in the day. Washed up north of here, on the public beach, in full view of retching sunbathers and a family reunion in full swing at the Sea Shell Motel. But barring that, what the buyer doesn’t know won’t hurt them. If the old man doesn’t want to talk about it and if the wife’s ghost doesn’t start slamming doors during a showing, then it’s full steam ahead.

A narrow boardwalk ran from a gap in the hedge and between the dunes to the beach. Cliff tested his weight on it. It’s in pretty good shape, Evan said. My son did some repairs a couple years ago to make it safe for his kids. I don’t go on the beach much these days.

63 the madison review

He looked away. Cliff felt fully alive only when people were paying him attention, and Evan seemed barely to be hearing him and so he was feeling close to invisible, not good for business nor his inner tranquility. Somebody will grab this place up in no time, he said. And he reprised all the positives, counting them off on his fingers. Evan was watching a pair of cardinals at the feeder; or rather, the male, bright scarlet, was at the feeder, and the female, muted earth tones, sat nearby in the old tree. Cliff nearly shouted, Am I correct that you’re not looking to buy?