16 minute read

COP26 marks a historic moment for humankind

Making <1.5°C work: Sumeet Ladsaongikar, Partner in Kearney’s Strategic Operations Practice, explains how to drive sustainability through manufacturing

Not long ago, government leaders gathered at the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in Glasgow to make policy commitments that will shape the future of our planet. The world now stands at a historic crossroads: our governments must act decisively to cut GHG emissions to net zero by mid-century, and control average temperature rise, or to face calamitous consequences such as the irreversible melting of the Antarctic ice sheet and a rise in average sea levels of more than 0.07 inches per year from 2060 and beyond.

Advertisement

COP26 focused on four core objectives: first, to secure net zero and keep 1.5°C within reach; second, to urgently adapt to protect communities and natural habitats; third, to mobilise finance; and fourth, to work together to deliver. Over the coming weeks and months, much of the attention will be on the government action needed to achieve these goals, but what really matters is how those commitments are executed at the gemba (at the place of action).

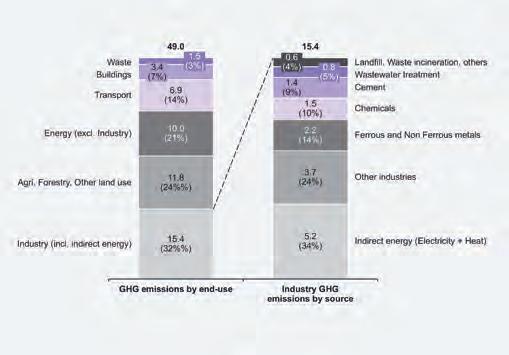

Manufacturing-based industry accounts for around 30% of direct and indirect global GHG emissions, as shown in Figure 1. Given the size of this contribution, both manufacturing companies and individual plants must play a leading role in tackling emissions if we are to respond positively to this pivotal moment in our history.

Making a change Multiple studies by the IPCC and other bodies offer compelling evidence that implementing known industry-specific and cross-industry levers can significantly reduce emissions. And the evidence also suggests that energy intensity in industry could be cut by around 25% from today’s levels through wide-scale upgrade, replacement, and deployment of bestavailable techniques (BAT) - especially in countries where these are not currently used, and in non-energy-intensive industries. In our experience, these initiatives often help deliver a marked improvement in cost performance too - particularly as technologies evolve and start generating a positive financial impact.

We have built on our deep expertise in operations and supply chain - gained over hundreds of manufacturing site improvement projects - and have created a framework to assess the maturity of manufacturing plants when it comes to key sustainability practices on environmental and social standards.

The framework features four levels of maturity (Stages 1—4), spanning 19 sub-dimensions of environmental and social standards, aligned to the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). However, the emphasis of this approach is on practice maturity, unlike the GRI, which often focus on reporting maturity. This ability to assess maturity is critical to identifying initiatives that can significantly reduce emissions.

Overall sustainability strategy maturity assesses the extent to which sustainability is embedded in the business strategy and in product and process technology for the plant. In addition, it looks at the portfolio of initiatives, KPIs, adoption of novel technologies etc. to achieve sustainability objectives.

Each individual topic area is assessed under environmental standards both on practice maturity and reporting maturity, with a primary focus on the practices adopted. For example, on materials, the assessment includes the maturity of sustainability practices in a plant along the following subdimensions:

a) Renewable/sustainable nature of materials used (including packaging) in production b) Extent to which the sustainability of materials influences product design c) Understanding of material mass-balance in the plant with continuous improvement programmes to tackle waste and improve yields

Fig. 1

Sumeet Ladsaongikar Partner in Kearney’s Strategic Operations Practice

Fig. 2

d) Rejection rates, reduction in rejection, and the extent to which rejected materials are reused/repurposed e) Extent of cooperation with community stakeholders (e.g., local municipalities) to improve recycling.

For each topic area, plants are assessed on Level 1 to 4 based on their practices, and highlight opportunities for improved sustainability and cost performance, leveraging a database of process and technical levers. For example, in several process industry plants (speciality chemicals, metal refining, cement manufacturing etc.), electric motors represent a major source of energy consumption in pumping, compressors, HVAC, and other applications.

A proactive strategy of moving to higher-efficiency-class electric motors, along with the adoption of variable speed drives to control speeds versus throttling using valves, can cut energy and equivalent GHG emissions by 5%-20%. Business cases made for reducing emissions need to account for the holistic impact - both in terms of financial and sustainability benefits - of any investment decision.

Similarly, using advanced analytics models to understand the precise range of material input and production process parameters, to drive optimal yield in chemical reactions or metal refining processes, can significantly reduce solid waste. This, in turn, can lower the need for recycling, cut energy consumption per unit of output due to higher yields, and create smaller waste streams.

Manufacturers cannot deliver this change on their own. Support of external technical partners becomes critical to quickly execute individual initiatives. Technical partners in sustainability across energy audit, software, and hardware solutions (for diagnostic, monitoring, and management of ESG elements), and highly experienced sustainability experts, are needed to support the assessment and solution deployment projects.

The human race has reached a pivotal point in its history. COP26 marks the moment for world leaders to act to preserve our planet for future generations. However, commitments to tackling GHG emissions must extend beyond governments: to deliver tangible, lasting change, those commitments must be championed - and convincingly executed - on the production floor of manufacturers across the globe.

Sustainability gemba

In our experience, conducting a three-to-fourweek sustainability gemba at individual plants represents a compelling way to:

• Assess current maturity level • Identify and quantify the impact of improvement levers • Build a roadmap of improvement initiatives • Identify external technical partners

Experience has taught us that the most effective approach is to undertake these gemba exercises at key plants that represent all major plant archetypes in a given manufacturing network, and then scale up these practices to other sites.

Sumeet is Kearney’s global 4-walls improvement lead and specialist in manufacturing, supply chain and end-to-end operations transformation topics Email: Sumeet. Ladsaongikar@kearney.com Co-authored with Teodor Stanilov, Manager, London Email: teodor.stanilov@kearney.com K www.kearney.com

A demand for supply

Fleur Doidge is a contributing writer to The Manufacturer and TM.com

where and when you want it

COVID, shipping and haulage issues, semiconductor shortages, changing workforce demographics, and Brexit are all hitting today's complex global supply chain

With supply chain disruption ongoing in a multitude of sectors, exacerbated by multiple factors from COVID to workforce demographics, the question has to be asked: how can manufacturing mitigate similar problems in future?

Jan Burian, Research Director at IDC Manufacturing Insights, says building in alternative options in defined, precise manufacturing is tricky. "As a first step, the supply chain might look at how it cooperates with research and development. It’s not just about being less dependent on certain materials or components," he suggests.

Technology is already disrupting supplier and OEM relationships in favour of online networks of certified partners. Trust and standardisation can be key here, as well as innovative vision, coupled with attention to people, processes and culture as well as technology, beyond simply identifying ROI opportunities.

Burian says: "It requires a lot of data and outside access to data."

He notes that some of this is already happening. IDC analysis suggests that 90% of global manufacturing supply chains had invested in technologies and business processes for resiliency by December 2021.

Data on hand for better decisions "Generally speaking the value comes from better enabling humans with information to make decisions," Burian says. "It's about sales, logistics, production, planning and R&D, and it's anything but one-solution-fits-all."

Emile Naus, Partner at consultancy BearingPoint, pinpointed long-term poor performance across the shipping industry, resulting in cuts to costs and capacity. But for Naus, the largest challenge is people. "Countries have ageing populations; youth is coming in with varying views on locations, hours and so on - hitting transport, warehousing and factories," he says. "Put everything together and it becomes quite a big mess."

Looking through a sustainability lens should help shorten supply chains, rather than offshoring to lower costs. Shorter chains typically have fewer links to go wrong, are more predictable and can be fixed more quickly because lead times are shorter too.

This should favour UK strengths in high-value products, and riskier products with a "real impact" if something goes wrong - although redeveloping skillsets and capacity is challenging.

De-risk your sourcing His prescription? Take a good look at sourcing, not just the cost per item but the amount of inventory required, and think about the risks, the sustainability impacts and "the smaller things" like ease of visiting, understanding the environmental footprint and overall visibility.

fixed more quickly. Emile Naus, BearingPoint

Naus’ advice is to look at digital twinning. A digital copy of your supply chain offers all the data needed to tell what's going on - from inventory to the pipeline of purchase orders, to components of supply via suppliers, contractors and sub-contractors.

Nitin Dsouza, Supply Chain Head at consultancy Publicis Sapient, adds that investment in intelligent ports will matter. "Today, you don't have a fully IoT-driven force telling you about congestion - although it will tell you there will be lots of ships waiting."

Dsouza agrees with Naus on a fresh workforce focus too - giving HGV driver shortages as a symptom. Skills require investment, and driving, for example, needs to hold appeal. "So take the employee lens and make sure you're pivoting as an employer of choice. That has to be an industry-led effort," he says.

Within the technology stack - the collection of computing hardware, software and services that supports an entire organisation - manufacturers should look at deploying flexible, composable setups to empower decision making across global supply chains.

For instance, if systems are interconnected and a logistics manager doesn't have to go in on weekends because data is available remotely, this can boost efficiencies and reduce unsustainable pressures on staff. Manufacturers must think further ahead to solve future supply chain challenges.

Richard Parkinson, Director at the port of Solent Gateway, notes that solving the supply chain requires accurate triage across workforce availability, at key air, land and sea nodes, looking too at governance and regulation.

If fewer ships are operating, and this means higher prices, incentives for more vessels might shrink shipping and container costs, improving volumes and delivery times, and international cooperation may be key, Parkinson points out.

Richard Eglon, Chief Marketing Officer at inventory-as-a-service provider Agilitas IT, agrees that sustainability and corporate responsibility should drive change, helping extend product cycles, incorporating product recycling and reworking where possible. "Industries are based around selling 'new product'," he says. "Only 30 years ago, a domestic appliance might have been more expensive but when something went wrong you had it fixed. This is the world we need to return to."

Eglon says that buyers are now better informed about their choices, competitive landscape and the provenance of product.

Collaborate to increase visibility Future inventory management requires vendors, suppliers and end clients to work together more closely and make supply chains transparent - digitising, automating and streamlining legacy manual processes and changing behaviours. "Firms taking a more collaborative and holistic view will succeed in coming years," Eglon predicts.

Paul Crutcher, Operations Director at Bisley, emphasises the criticality of reducing single points of failure across supply chains. "You've got less of an opportunity for the physical logistics side of things to interfere," Crutcher explains. "A resilient supply chain or distribution system has multiple nodes."

He points out that partly because China has become such a massive global node, even if Chinese supply is cut for a couple of months, with no Plan B the resulting knock-on effects can be enormous. "There's an argument for reshoring where it's economically sensible," he agrees. "And apparent foes actually have a lot to gain from collaboration. Often they're competing for part of the same supply

ABOVE: Bisley's Paul Crutcher: "A resilient supply chain or distribution system has multiple nodes."

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Global supply chains have seen longstanding issues balloon postCOVID

Industry and sector disruption is huge and will continue Future-proofing manufacturing supply chains require a long-term approach Collaboration, coordination and data are key to transparency and visibility Governments, industry bodies, financiers and others must play a role

IMAGE ABOVE: eilis-garvey/unsplash chain. Together, you can find ways to mitigate instability."

Rivals may often have different core differentiators when it comes down to creating value. Pinpoint these, then resist the natural tendency to be parochial about data, and work out how to collaborate in other areas, he suggests.

Also, although lean favours a one-piece flow, companies have a tendency towards batching - ultimately hurting the supply chain as a whole. Doing things in batches is less efficient, Crutcher notes. "What you want is to have truth at the point of consumption, all the way across the supply chain so everybody is aligned with the same rate of demand."

Dr Jagjit Singh Srai, Research Director at the Institute for Manufacturing (IfM), says reconfigurations might harness ecommerce platforms to draw in thirdparty logistics providers from different resources, for example. "Those who are more modular in their products can flex their resources much more effectively - responding quickly, in a more agile way, to changes in demand," he adds. "The issue is that nobody wants to pay for an idle factory, waiting for a crisis. And the reality is that if the crisis hit, you wouldn't have any people to run that factory."

What then is the answer? Consider all pinchpoints and segments Srai suggests careful triage of pinchpoints where some slack can be introduced. Segmenting a supply chain into multiple tiers at a significant distance from the consumer introduces vulnerabilities. This means designing shorter supply chains where possible, Srai explains. "Understand the potential decoupling points where stock can be held that can be quickly used to serve a particular demand. And some of those need to have business in normal times for them to be able to respond and ramp up in extraordinary times," he says.

Will prices rise? Not necessarily, Srai says, because people are already "paying through the nose" due to supply chain failures and slowdowns. Correcting failures is costly too, while supply chains are generally reconfiguring at some level all the time.

Sometimes interventions can have unintended consequences - like when personal protective equipment (PPE) was being procured by different UK regions competing with each other, he says.

Strategies to stabilise supply might include collaborative reduction of port bottlenecks for haulage. Sharing of fleets and warehouses among organisations may also help build resilience. Public-private partnerships could be looked at, and deeper infrastructure investments are crucial.

led effort Nitin Dsouza, Publicis Sapient

ABOVE: IfM's Jag Srai: "The issue is that nobody wants to pay for an idle factory, waiting for a crisis. And the reality is that if the crisis hit, you wouldn't have any people to run that factory."

Formulate predictions and take action, he urges. The fact that forecasts are often wrong doesn't mean you shouldn't make the attempt. "And you can't really wait for a crisis."

Money, laws and licensing Tony Lock, Distinguished Analyst at Freeform Dynamics, notes that politics, differing restrictions and licensing regimes globally are also problematic. Less often considered: the role of financial services.

If you don't have access to raw materials - an obvious example being rare-earth metals for batteries - you not only have to bring them in but convince accountants and financiers in Wall Street, the City of London, Singapore or wherever. "Not having stock should no longer be seen as a real positive," says Lock. "I'm worried about convincing financial markets of the need to rebalance away from just-in-time, from having nothing on the books until you're producing, and then getting it out the door as quickly as possible. The whole accounting side is a big issue that needs addressing."

Governments could potentially implement some form of legislation that requires industries to have stocks onshore to buffer price spikes - helping avoid UK situations like being caught without enough gas. Legislation can shift industries towards recycling, looking at what they're making and how they're making them, increasing collaboration and more. "Sustainability and green footprint can be legislated for and there'll be more requirements on organisations to improve their supply chains from that side," says Lock. "I just hope that those financial people that really control everything can recognise those changes in the wind." Alex Dalton, Managing Director of woodworking machinery supplier Daltons Wadkin, has found lead times of three or four weeks rising to four or six months on some items. Prior to COVID, issues were mostly accommodated. "I think before COVID there was a certain amount of blissful unawareness of how these things work behind the scenes; we are now acutely aware of everything that must fall into place at a certain time to make things happen," he says.

Daltons Wadkin has already invested in management software that can bring multiple different data sets and spreadsheets in one central location, enabling instant progress updates, points-of-sale information, delivery updates, job data and more. "It's all about communication, really," he points out. "If everybody's talking to each other, you better understand needs that everybody has."

Bulk-buying of capital industrial equipment can offset storage costs, so there are ways to gain as well as lose by adding slack to improve overall resilience. Government, industry groups and research organisations can work better together to develop better policies, frameworks and other superstructures. But getting individual companies collaborating might be tricky, he feels. "I suspect many might shy away."

MANUFACTURERS RESPOND

Tony Hague, CEO of PP Control & Automation, notes that OEM machine building has been hugely disrupted in recent years, and sees the long supply chains centred abroad as the largest problem. "Start with a cross-party governmental manufacturing strategy. The problem is that each government comes and goes and tends to blame the previous government for not doing something," Hague says. "We need a long-term manufacturing investment strategy blueprint for the UK, regardless of who's in power. That's where it has to start so that it can cascade down from there."

Manufacturers can encourage things "in a smaller way" within their own industry, and right now there's an appetite for it, he says. "What worries me is we won't do that for two or three years."

Jason Webb, Operations Director at food thermometer maker Electronic Temperature Instruments (ETI), agrees that supply chain transparency should help. This means data driven insights via technologies such as data analytics. And he agrees on the need for longterm strategy and investment by government. "Delays at Dover at the end of 2020 and the more recent vaccine rollouts have demonstrated the challenges of keeping refrigeration temperatures steady during transit - where technologies such as wireless data loggers have helped ensure safe passage, transmitting temperature data to the internet," Webb explains.