13 minute read

TECHNICIAN UPDATE

Breaking the Pain Cycle of Kissing Spine

By Emily Brooks

Dorsal spinous process impingement, or kissing spine, has long been a contributing factor in idiopathic lameness and has frustrated veterinarians and owners alike. As the equine veterinary community continues to try to understand the importance the role that the spine, pelvis and the sacroiliac joints play in soundness and longevity of sport and racehorses, the need to accurately diagnose and treat kissing spines has grown.

No matter your case population, chances are you have seen a horse with back pain if you are at all involved in lameness. Recently, I was involved in a case that took several years to hash out and showed the relevance of the pain cycle in other aspects of horse health.

An 11-year-old off the track Thoroughbred with a successful racing career became a sport horse project at the age of 4. The 17-hand gelding started a successful eventing career with professional 5-star rider in Lexington, Ky, when he began having issues with inconsistent performance, specifically in the cross-country phase.

The professional sold the horse to a young student and the pair was successful through novice/training level. When trying to move up a level, they began having the same performance issues as the more skilled rider. The owner brought the horse to me to try and show and sell, despite the recent poor competition record and behavioral issues.

The gelding’s vices included neurotic weaving when stalled or tuned out alone, teeth grinding, during work and stall walking. The horse was in good body condition, but lacked a top line, or proper muscling over his back and hind quarters. I assumed this was due to lack of consistent work.

Based on the horse’s behavior, I recommended either having a gastroscopy performed or treating for gastric ulcers before I attempted to compete or sell him. The owner elected to treat for ulcers rather than spend the money for a gastroscopy. The horse was put on omeprazole daily for 3 weeks. It should be stated here that the owner is a boarded equine surgeon, so he prescribed the treatment. After 1 week of the oral omeprazole, the teeth grinding resolved, though the weaving and occasional stall walking persevered. I assumed that was just the horse’s learned behaviors. I increased turn out as much as possible, changed the feeding program to include alfalfa prior to exercise, and the horse’s performance in dressage remained very good. After several months of dressage training and only minor behavior issues under tack (spooking, occasional rearing, etc.), we began jumping.

The horse has a natural talent to jump but liked to get very close to the base of the fences, which was noted as his possible style. The gelding won his first 2 novice events with the lowest score of the entire show. I moved up to training level, winning 5 of 10, and placing in the top 3 of all shows entered. When preparing to move up to preliminary level, teeth grinding began, as well as hard spooking and refusal to move forward toward jumps, resulting in elimination.

Due to difficulty at this point being able to sell the horse, the owner transferred ownership to me to be rid of the expense. My experience has taught me that horses do not lose talent overnight. Poor performance or behavior changes are the only ways they can communicate pain in absence of an obvious lameness.

I opted to have a gastroscopy performed, and glandular and squamous ulceration was present. The horse was prescribed a treatment of omeprazole, sucralfate and alimend. The feeding plan was followed rigorously, with the omeprazole being administered when fasted, 30 minutes prior to feeding. He was given 30 days off while being treated for the ulcers and was to have a follow up gastroscopy prior to returning to work. On the repeat scope the ulcers had completely resolved. After discussion with the internist, it was decided to continue with a low dose of omeprazole for the first 30 days in work, and to treat with a full tube daily when traveling or competing.

When put back into work the horse’s performance was as it had been prior to the eliminations. Jumping was much better, and he appeared more willing to leave from an appropriate distance and stretch out over fences. Notably, with the return to rigorous training he had still never developed a topline as most eventers do, although his gluteal muscles were very well defined. He also had shown much sensitivity to grooming and girthing, though his “thin skinned” nature was often to blame.

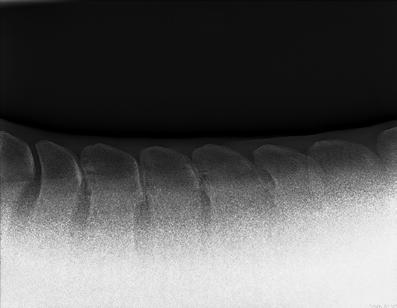

At the time I was competing the horse, I was working at a different clinic. I brought him in to use for a model while teaching a radiography lab to the interns. As luck would have it, taking thoracic and lumbar spine views using a Canon wireless DR 14”x17” plate showed several areas of dorsal spinous process impingement.

I showed the findings to his previous owner but he did not think they looked bad enough to be clinically relevant. The only maintenance that the horse had ever had during his eventing career was occasional hock injections, which were described as beneficial by the previous rider. The horse had never been blocked for lameness to my knowledge.

We went on from there and had a stellar competition season, qualifying for the 2021 Training Level American Eventing Championships at the Kentucky Horse Park. He had been tolerating the training very well, and I continued the lower dose omeprazole in hopes of mitigating ulcers due to increased workload and stress.

The horse performed and scored very well in dressage, finishing fifth out of forty-five horse and within 4 points of first place. We went into cross country with every intention of jumping clear and fast. The first 18 fences were the most athletic and brave I have ever felt that horse jump. It was surely the most technical and difficult course I had ridden with him, as it should be during a championship. Fence 18 was a very large and wide-open oxer. He took the longer spot but jumped well out of stride. Upon landing we galloped well away, but I could tell the extra effort over the wide jump had jarred him slightly. Rounding the bend to the water complex he backed away from the gallop and refused to move forward. When I attempted to circle and re-approach, he reared, and I could tell he was done for the day.

After the show another gastroscopy was performed. Again, the squamous and glandular ulcers were back, despite the continued low dose omeprazole. This time we added misoprostil to the previously prescribed regiment and omitted the sucralfate, and again we gave him time off.

At this point in time, I began working for a different surgeon who is also boarded in sports medicine. I asked him to look at the horse with a fresh set of eyes. He watched the horse jog and then palpated his legs and back. Baseline lameness was 0/5, though the horse seemed stiff behind on the straight line and circles. When the vet palpated the lumbar region, the horse responded by nearly buckling to the ground. His pain response was noted as marked. Review of the radiographs taken previously showed narrowing of the thoracic facets as well as the areas of impingement. This doctor recommended injecting the facets with Serapin and seeing if there was any improvement. He was doubtful that this would have any lasting effects, but wanted to prove that treatment would improve the pain prior to considering ostectomy. Use of a Pessoa training system or Equiband was also recommended to help strengthen the longissimus dorsi muscles and stabilize the back.

Resolution of palpable back pain in the lumbar region lasted for approximately 30 days. At that point I opted to have the surgery performed as a last-ditch effort to see if this horse could ever hold up to upper-level competition. We discussed at length the rehabilitation program post-surgery, as that has been determined to be as important as the surgery itself.

On Dec. 20, 2021 the horse had dorsal spinous process osteotomy on 5 sites deemed clinical on radiographs and palpation. Surgery was performed standing in stocks while a Detomidine CRI was given via intravenous route while under supervision of an anesthetist. Segments of the dorsal spinous processes were removed using radiograph guidance. Throughout the procedure the distance between dorsal spinous processes lengthened dramatically. Post operative instructions were to give 1 gram of phenylbutazone IV every 12 hours for 4 days and then decrease to 1 gram once per day for another week. Due to the known history of gastric ulceration a full dose of omeprazole was given as well. The horse was to be confined to a stall for 3 weeks, hand walk for 1 week, and then begin small paddock turn out for 2 weeks before increasing turn out size. The horse would have a total of 4 months off work and then groundwork could begin, starting with long lining in an Equiband system. If exercise was tolerated well for1 month we could begin work under tack.

With my background in equine rehabilitation I decided to be very systematic in the approach to bringing him back. Once the sutures were removed at 14 days, I began doing carrot stretches, making the horse stretch left, right, and between his front legs, holding each stretch for at least 5 seconds. This proved helpful during grooming sessions while trying to keep him from being too pent-up during stall rest. After the prescribed rest we began work on the long line with the Equiband. I started with 15 minutes of walking with frequent transitions to halt and changes of direction. Care was taken to work each direction equally. After 2 weeks trot was integrated for a total of 10 minutes each direction maximum. Fatigue was always noted, and sessions would be shortened as needed. Immediate changes in the horse’s gait were noticed, including improvement in suspension and swing of the hindquarters in both walk and trot.

It is very easy to quantify decline or improvement in racehorses since talent is based on time. Fractions are noted and catalogued, and race results are easily tracked. Sport horses don’t allow the same statistics because performance can be altered based on so many factors. It isn’t just the horse that finishes in the shortest amount of time, and dressage is a tediously subjective discipline. Much of what we know about performance is based on rider testimony.

Fortunately, my months of time spent with this horse allowed me to say with certainty that his overall attitude had improved, and he was moving with more ease and less tension than had ever been experienced.

After following the discharge instructions, I began riding at the 4-month post-op mark, with a conservative increase in time under tack and intensity of work. Throughout the rehab, I was constantly aware of the possibility of ulcers returning. It became clear that the horse had been dealing with chronic pain for years, and that had likely been the cause of the ulcers returning regardless of treatment and proven resolution. My hope was obviously that breaking the pain cycle would keep the ulcers from returning, and that upper-level competition could finally be achieved.

The summer was spent slowly increasing work and continuing with the Equiband twice per week. The surgeon came to check the horse’s progress after 6 months and was pleased with the response to surgery and lack of any response to palpation of the back . The horse had also gained approximately 200 lbs after surgery, mostly in muscle and top line.

At the time I was putting this report together, this horse won his first competition back by 5 points, with no penalties in the jumping phases.

Another scope was done to find out if the ulcers remained resolved in the absence of back pain, and none were seen. His behavior has remained much calmer with no bruxism or weaving. We continue to manage him with free choice alfalfa and omeprazole during times of increased travel or stress. I am hopeful, I can compete him at the 1-star level next spring. We plan to evaluate his soundness and scope for ulcers every 6 months.

Teaching Points

Possibly one of the most important realizations of this case is that there is no obvious scale for overriding or impingement of dorsal spinous processes. Unlike recurrent laryngeal neuropathy or neurologic disease, there is not a scale that can be used. What radiographs look like versus what each individual horse can tolerate is so varied. Very successful competition and racehorses have worse radiographs than my horse and carry on without ever having back pain.

The important point is that each horse is different in the level of pain it experiences and can endure. Our jobs as riders and caretakers are to listen when they try to tell us something is wrong. Many horses are written off as poor performers, although in my experience inconsistency in performance in the absence of obvious lameness is the most telling sign of an underlying problem.

In this case the ulcers became the red flag much sooner than the chronic pain.

About the Author

Emily Brooks has worked as an equine veterinary technician since 2007, starting her career at Rood and Riddle Equine Hospital. Her interest quickly focused on advanced diagnostic imaging modalities and there she ran a high-field MRI, CT and performed musculoskeletal ultrasound for lameness exams and surgery. Emily has traveled to the Equine Veterinary Medical Center in Doha, Qatar, to help set up their imaging center in 2018 and now works at Kentucky Equine Hospital as the head Imaging Technician in Simpsonville, Ky. She also runs a sport horse rehabilitation facility and trains and shows dressage horses and eventers