5 minute read

The Christian Vocation: A Calling to Holiness...and Hope

Dr. Paul Blowers, Dean E. Walker Professor of Church History, Milligan University

In the early Christian period, several biblical interpreters exploring the details of the creation story in Genesis 1 (called the Hexaḗmeron/Ἑξαήμερον) or six-day creation account) noticed many subtly important nuances in the text that carried significant meaning for the Church. In the Septuagint’s Greek translation of the original Hebrew, for example, they noticed in Genesis 1:26–27, the creation of humankind, that not only did the text have the Creator referenced in the plural (“Let us create humanity…”), usually understood as the whole Trinity involved in the creation, but there was also a distinction between the “image” and “likeness” of God in which humanity was made. The “image” (eikṓn/εἰκών) appeared to be primarily a natural God-likeness in humans’ created nature; but the Greek word usually translated “likeness” (homoiôsis/ὁμοίωσῐς) is more accurately rendered “assimilation.” Many of the Greek Church Fathers, who favored the Septuagint as the truly inspired scriptural text, took this to mean that the divine “image” is the divine gift of God-likeness endowed in human nature, while the “likeness” had to do with humans’ process of growth through this life in assimilation to God.

Advertisement

Our true likeness to God is something that must be actively pursued and perfected. Assimilation to God is our long-term vocation as human beings gifted with reason, free will, and deep-seated desire.

Even Plato had spoken of the soul being summoned to “assimilation to God so far as possible” (Theaetetus 176b). However, various ancient Christian authors like Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Gregory of Nyssa, and others, though appreciative of certain aspects of Platonism, focused on the fact that Christians’ assimilation to God, being their lifelong vocation, not only required a whole regimen of moral and spiritual disciplines, but that the ultimate perfection of humanity had “arrived” in the person of Jesus Christ.

By this account, Christ was not only the model of human integrity and virtue, worthy of imitation, He was the new Adam (1 Corinthians 15:45–49; Romans 5:18–21) who in His incarnation, cross, and resurrection transformed humanity’s very future, both rectifying the disobedience of the first Adam and his progeny and opening them to a glory never achieved in the primordial paradise of Eden. For this reason, many early Christian theologians were as interested — if not more so — in the vocation of humanity as in human nature as such. Even though various writers used the language of humanity’s universal task being a “return” to paradise, the hard existential fact was that the past could neither be recovered nor “fixed” after the fact of the Fall. Human history moved relentlessly forward, such that pining after a “paradise lost” could never suffice. Christians needed to face the future with confidence in, and assurance of, the faithfulness of God supremely demonstrated in Jesus Christ. They were called to live out their own faithfulness before God, in all the different forms that it would take: continuing repentance, death to self and self-interest, obedience to Christ’s commandments, inculcation of Christ’s virtues and overall holiness, abiding participation in the sanctifying worship and Sacraments of the church, and so on.

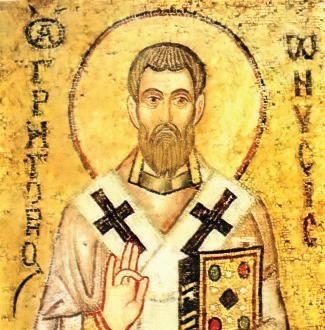

St. Gregory of Nyssa (335-395)

The apostle Paul himself had already emphasized the future-oriented character of the Christian vocation. In Ephesians in particular, he meditated on the magnificence of the Creator’s plan for the human race. Even before the foundation of the world, Paul declared, God had “chosen” humanity to enjoy His grace, “that we should be blameless and holy before him” (Ephesians 1:4). “He destined us in love to be his sons through Jesus Christ, according to the purpose of his will” (1:5). “We who first hoped in Christ have been destined and appointed to live for the praise of his glory” (1:12). Simply put, our human vocation is the active worship and enjoyment of our Creator. Further into Ephesians, Paul accentuates the fact that our human “calling” is a calling to hope (1:18).

The early Church persistently sought to maintain the vocation of all Christians. Being a part of the Church — by definition, the community of the “called out” ones (ekklêsia/ἐκκλησῐ́ᾱ) — is a matter of living up, through faith and holiness, to a hope in the God who is always doing a “new thing” among His people (Isaiah 43:19; Revelation 21:5), guiding believers into an uncertain but ever promising future.