7 minute read

What’s in a Portrait?

by Hilary Anderson Stelling, Director of Collections and Exhibitions, Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library

A portrait is someone’s likeness captured in paint, ink, or in a photograph, but it is also much more. Portraits serve many purposes: they function as personal and family mementos, document accomplishments, or show the owner’s admiration of a celebrated figure. They help us remember past lives. The portraits in the collection of the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum and Library tell the story of the many people who participated in and shaped Masonic and fraternal organizations in the United States for over 200 years.

Artist Joseph Davis specialized in images that combined profile portraits with the kind of information found on family records. Here he depicts a husband, wife, and their young son. While Mehitable Wentworth holds her new baby, her husband Andrew grasps objects associated with Freemasonry in his hands—a membership certificate or chart, a square and compasses. The tools may have held a double meaning for Andrew—census records list his occupation as “Mason.”

Andrew, Daniel, and Mehitable Wentworth, 1833. Joseph H. Davis, Berwick, Maine. Special Acquisitions Fund, 90.32. Photograph by David Bohl.

Famous Masons

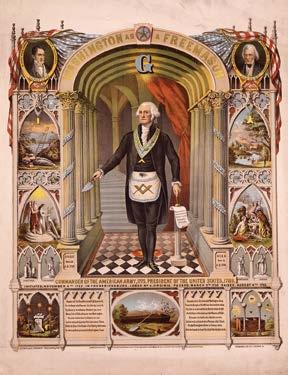

In the past, many people valued portraits of important and recognizable figures. Nineteenth-century printmakers and publishers capitalized on their fame of some leaders, like George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, and created images portraying these revered figures in their roles as Freemasons to appeal to Masonic consumers. Brethren could purchase affordable prints of these subjects to display in their homes. These images were also part of the décor of many Masonic buildings where portraits of well-known Freemasons reminded members and visitors of these admired heroes’ connection with the fraternity.

Starting in the 1860s, prints of Washington as a Freemason were particularly popular. This colorful version also featured small portraits of two other well-known Masons, the Marquis de Lafayette and Andrew Jackson.

Washington as a Freemason, 1870. Strobridge and Co., Cincinnati, Ohio. Special Acquisitions Fund, 78.74.18.

Signs and Symbols

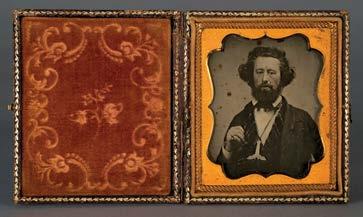

Men have long taken pride in their association with Freemasonry. In the 1800s and 1900s, some Masons commissioned portraits of themselves and, in them, chose to be presented as members of the fraternity, wearing jewelry or regalia that identified them as Freemasons—along with their best and most fashionable clothing. Some of these portraits marked personal achievements such as serving as a lodge officer, while others included more subtle indications that the subject belonged to a fraternal group.

The subject of this portrait wears a Royal Arch sash and apron. The color and metallic highlights added to the image draw attention to subject’s regalia.

Man in Royal Arch Regalia, 1850-1860. Museum Purchase with the assistance of the Kane Lodge Foundation, 2010.010. Photograph by David Bohl.

Jewels of Office

In Masonic and fraternal organizations, officers wear different badges that indicate their roles, such as lodge Master or Secretary. These jewels take the shape of a symbol important to the organization, such as the square, the emblem of the lodge Master and a symbol of virtue in Freemasonry, or are formed out of emblems that reflect the work of a particular office. A lodge Secretary, for example, wears a badge in the shape of crossed pens—implements related to the role he fills.

Along with his street clothes, the subject of this portrait wears a Senior Warden’s jewel in the shape of a level suspended from his neck. In a Masonic lodge, the Senior Warden is the second-highest ranking officer after the lodge Master. His badge of office, the level, symbolizes equality among lodge brethren.

Senior Warden, 1840-1860. Museum Purchase, 2001.070.1. Photograph by David Bohl.

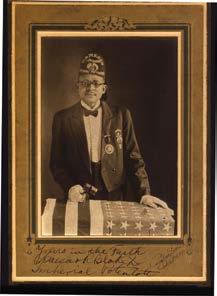

Jewelry, such as small pins and badges worn as part of everyday dress, offered a clue that the subject of a portrait belonged to a fraternity. Paintings and photographs of Freemasons in their regalia—the jewels, aprons, collars, sashes, hats, and other special clothing that they wore to meetings—conveyed more information, especially to fellow members. These items tell the viewer that the subject of a portrait prized belonging to a fraternity. Particular aspects of regalia and badges also communicated to others what group the subject participated in or what office he held. In presenting himself as a Freemason, a portrait’s subject proclaimed his affiliation with the group as a valued part of his selfidentity. He also guaranteed that he would be remembered as such for as long as the portrait endured.

A clerk with Norfolk and Southern Railway, Caesar R. Blake was a member of the Ancient Egyptian Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, Prince Hall Affiliated (A.E.A.O.N.M.S.). Also known as the Prince Hall Shriners, founders established this group in Chicago in 1893. Blake belonged to Rameses Temple No. 51 in Charlotte and served as Imperial Potentate of the A.E.A.O.N.M.S., from 1919 until his death in 1931. In this portrait, he wears a fez and jewels associated with that office.

Caesar R. Blake, Imperial Potentate, 1919-1931. Carolina Studio, Charlotte, North Carolina, Museum Purchase, 99.044.1.

Family Portraits

In the early 1800s, an increasing number of artists and folk painters plied their trade in American cities and towns. Those who could afford it could choose to have their family member’s portraits painted to preserve a faithful likeness and a moment in time. Although a painter captured a subject’s likeness with his skill, he did not work alone. The subjects of the work often helped shape the final product, deciding how to present themselves in the portrait. In the mid-1800s, the advent of photography brought portraiture to the masses and the tradition of sitters helping craft their own presentation continued. The subjects of these portraits decided what to wear, what to hold in their hands, and how to pose for the photographer to convey information about themselves and what they valued. In many cases, the subject chose to be depicted in his Masonic apron or wearing a fraternal pin in the context of a family portrait, showing how his membership formed part of his identity.

This pair of cased tintypes shows a woman with a baby and a man wearing a sash and a Masonic apron. Together, these images depict a family. To make a good impression, the subjects of these portraits wore their most fashionable clothing. After the portraits were taken,

Family Portrait, ca. 1860. Special Acquisitions Fund, 88.42.19a-b. Photograph by David Bohl.

the photographer highlighted the woman’s brooch and the decoration on the man’s sash and apron with gold paint.

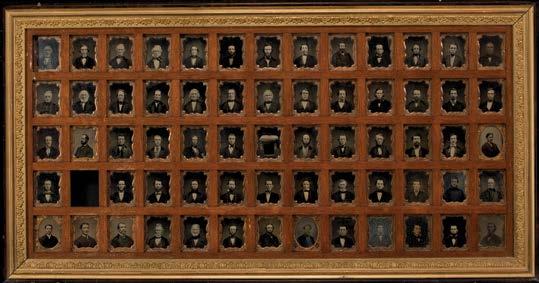

Photographic group portraits often documented special events such as an important meeting, a rare gathering, a new lodge, a celebratory excursion, or the election of new officers. With photography, this kind of portrait could be taken with relative ease and manageable expense. Photographic portraits became increasingly common into the 1900s and offer the modern viewer the chance to learn about the people and groups depicted in them. We can better understand these images when we ask the question, “What does this portrait tell us?”

A new lodge room or the election of a new group of officers at a Masonic or fraternal lodge sometimes prompted the creation of a photograph to celebrate and document the event. In 1861, for example, members of Altemont Lodge No. 26 in Peterborough, New Hampshire, agreed to use lodge funds to pay for a “Miniature Frame” to be made and hung in their lodge room. This frame of miniature portraits would include “every Master Mason in regular standing in town”—be they a member of Altemont Lodge or not. Masons in the area were “...invited to deposit their ambrotypes with those of the Brothers of the Lodge.” Members of Altemont Lodge paid for their own photographs displayed within the special frame that the lodge had made. The frame cost the lodge seven dollars. Some of the men pictured here had their portraits taken by George H. Scripture, a Peterborough photographer and area Mason.

Members of Altemont Lodge, Peterborough, New Hampshire, 1861. Museum Purchase, 2001.063. Photograph by David Bohl.

Dressed for a summer excursion, the women and men in this image—a souvenir photo postcard—hold pennants created to commemorate the event.

King Oscar Lodge No. 855 Chicago, Illinois, 1916 Outing. Ansco Company, Binghamton, New York. Museum Purchase, A96/066/0880.

When the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library is again open for visitors, come see these portraits and more in the gallery exhibition “What’s in a Portrait?” In the meantime, we invite you to explore some of the images and objects in the exhibition in an online version, which you can see at: SRMMLOnlineExhibitions.omeka.net. If you have questions about making a donation to the museum collection or would like to let us know what you think about our online exhibitions, please drop a line to hstelling@srmml.org.