13 minute read

Two Feminist Wars Fought in the Kitchen’ // Izzy Woods

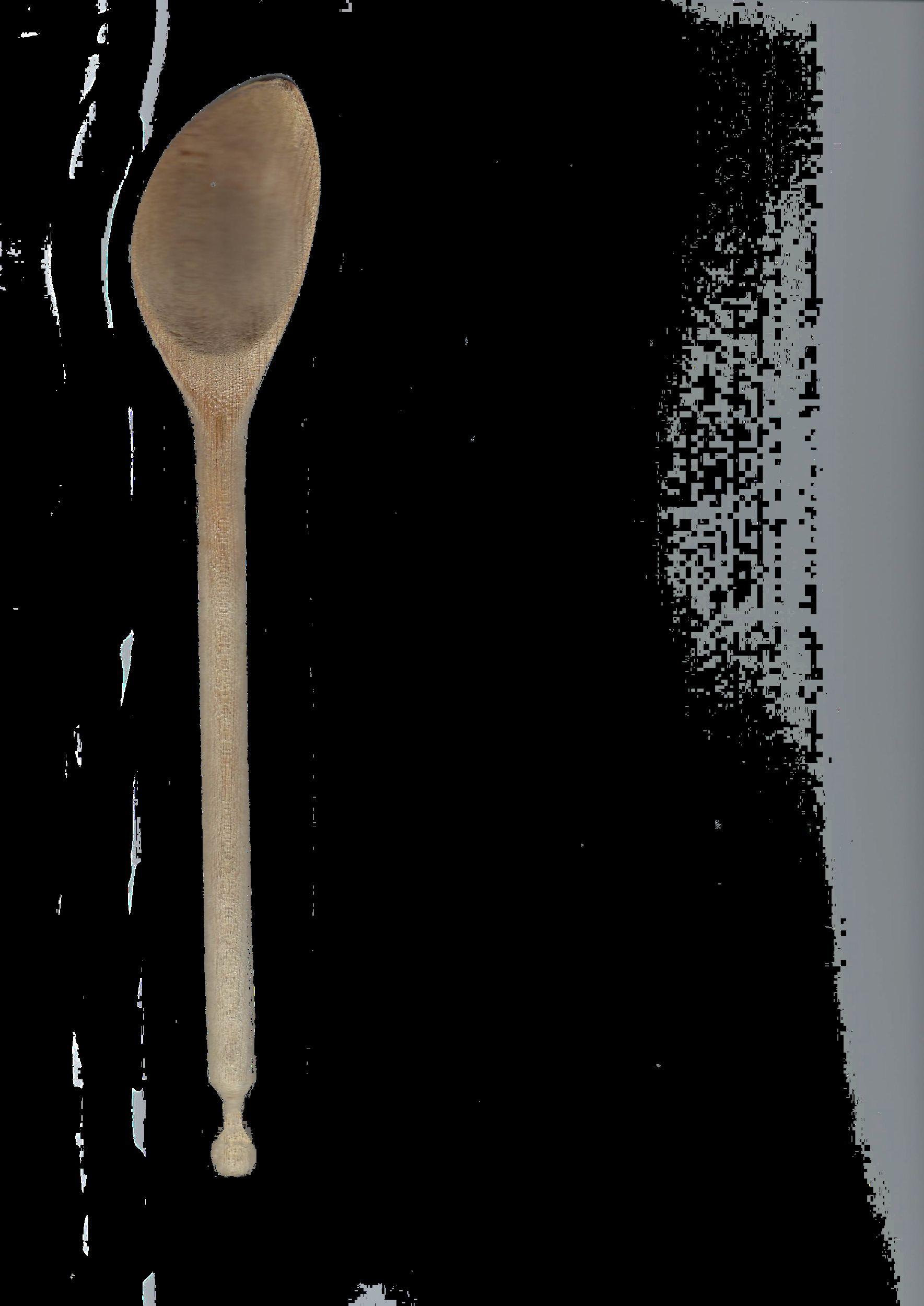

My favourite thing that I own is a wooden spoon, given to me on my previous birthday. It belonged to my grannie, and her mother before that. I spent a lot of time with Grannie in her kitchen, and I always insisted on using this particular spoon for whatever sweet treat we were concocting. It’s an unusual shape: instead of the oval shape you would expect from such a utensil, the bowl of this spoon has a sharp point with a beautiful rounded slope back down to the handle. When I asked Grannie why it looked like this she told me it had been slowly worn down over the last hundred years or so from the sheer pounding it was exposed to. As someone who is a sucker for some family history, this delighted me. The thought of this familial line of women, each beating cake mix, or Yorkshire pudding batter, or pastry, or whatever treat would be on the table that night to within an inch of its life was so wondrous to me. It still is, and I like that I am the next person to own this spoon.

To me now, the spoon embodies long histories of women working in the kitchen. Historically the role of food preparation and feeding was attributed to women because of their ability to breastfeed, with certain social conditions (namely lack of childcare and participation in the workforce), solidifying women’s role within the family. [1] As women were largely excluded from the workforce, they fulfilled this role by preparing dinner for their husbands, to be ready when they returned from work. [2] According to data published by Suzanne Bianchi, in 1965 women were cooking for over nine hours a week, in contrast to one hour for men. [3] Even after women were widely employed in the workforce during both world wars, once they were over they were expected to give up their wartime jobs and resume their roles as housewives. Exacerbating this was the myriad of advertisements in the 50s, 60s and 70s which endorsed the role of women as homemakers.

Advertisement

While the idea of a kitchenless home has been part of Western feminist ideology since the 19th century, it wasn’t until the advent of second wave feminism that the kitchen explicitly became the Enemy Of Woman. To some second wave feminists, cooking reflected women’s oppressed status in society, both inside and outside the home. In 1968 a group of feminists dumped a pile of aprons in front of the White House, symbolically rejecting the traditional notion that cooking is women’s work. [4] Meanwhile Ann Oakley stated that “housework is directly opposed to the possibility of human self-actualisation”, and called to abolish the housewife role. [5] Similarly, one of feminist magazine Spare Rib’s early subscription gifts was a purple dishcloth that read: ‘First you sink into his arms, then your arms end up in his sink.’ The magazine wanted to distance itself from the standard housewifey rhetoric found in publications like Woman’s Own, and banished cooking from its pages altogether. [6]

As a result of this new wave of feminism, artists were compelled to reconsider domesticity, and to contest the nostalgic visions of the domestic sphere as a space of comfort and security that had been pushed onto women from the end of the second world war. [7] Feminist artists 19

Above: Nancy Woods in Miranda, 1954. Right: Martha Rosler, Hot Meat, c. 1966-72.

of the period turned to motifs of the kitchen, and domesticity in general to critique their relegation to the home and their depiction in pop culture. This mode of representation was revolutionary at the time, with feminist artists drawing from their own experiences, specific events and narratives from daily life. And of course for many of these artists, their daily life meant dealing with the expectation that they would be the ones putting dinner on the table.

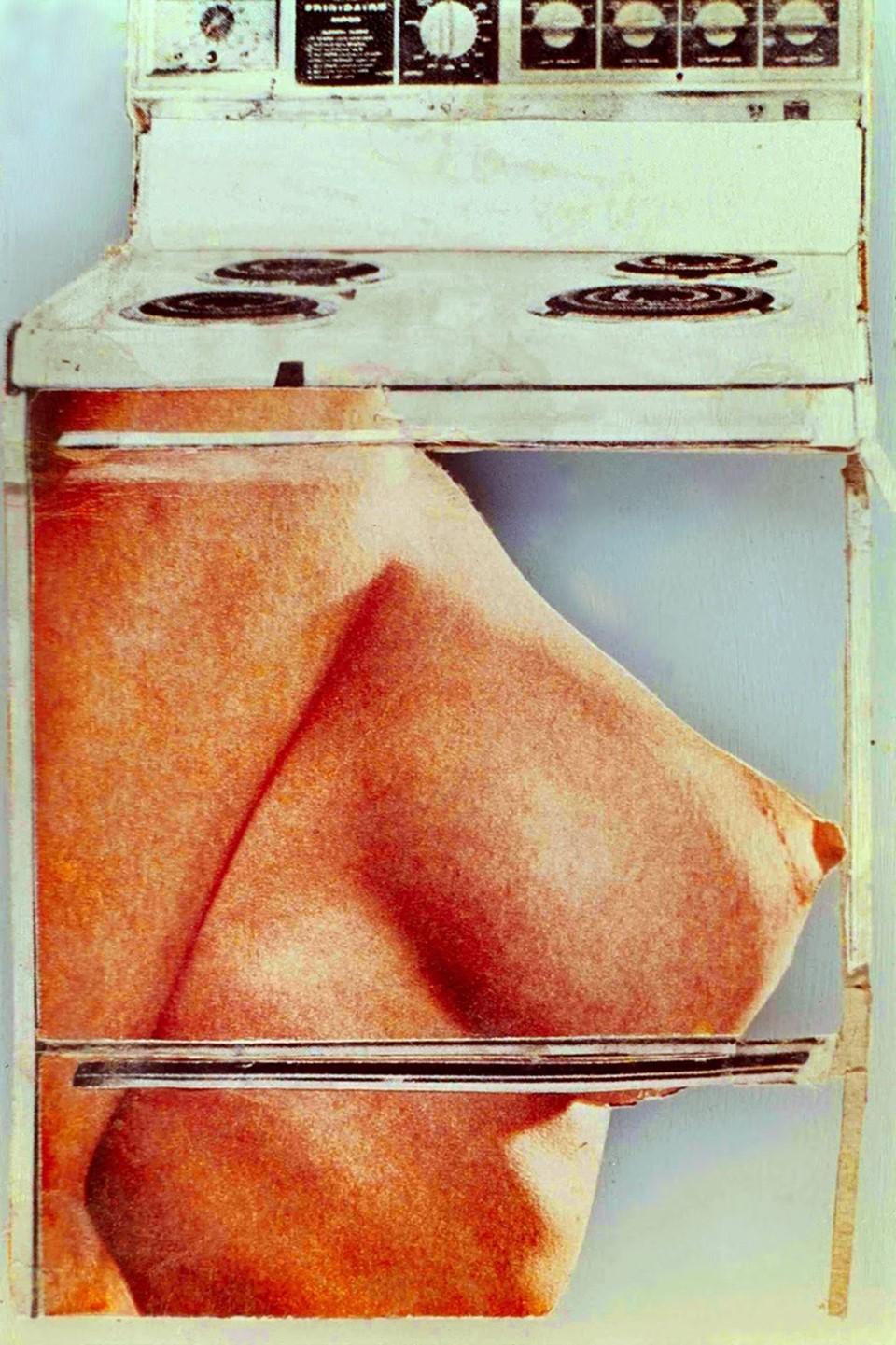

Pop art began in the mid 1950s, quickly becoming a global movement that focused on a language of protest, often engaging with the changing societal order and the influence of mass consumption. Colours and motifs from popular culture became symbols for critiques of the current socio-political orders. While most Pop artists mirrored the patriarchal values found in the media, some feminist artists embraced popular culture to voice their ideology. The sudden boom in consumerism meant there was an increase in the manufacture of household items, and given the nature of many of the advertisements selling them, feminist artists had much to critique in their work. While some of this work concentrated on the negative way women were presented as traditional objects of male possession, other artists presented the home as a liberating site of female creativity and sexuality. [8] Martha Rosler combined these two aspects of female experience, critiquing the patriarchy, consumerism and the pervasive sexism of popular culture.

Her series Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain (1965) was disseminated in underground, mainly feminist, newspapers. In the series, a fridge, a washing machine and an oven are covered with cut-outs of female ‘meat’ from the pages of Playboy. The jarring combination of the domestic appliances with the images of women’s bodies causes the viewer to consider the contradictions in stereotypes of women, e.g. being domestic and docile but also sexual and objectified. This contradiction was analogous of women’s position in 1960s consumerist society, where, as Linda Nochlin argued, ‘women were the 20

Above: Rosler, still from Semiotics of the Kitchen, 1975. Right: Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled from Kitchen Table Series, 1990.

primary agents of consumerism and yet were frequently objectified in popular culture as if to be consumed.’ [9] Rosler also plays with the fragmentation of women’s bodies, and aptly calls this photomontage from the series Hot Meat, where the female body is shown only in part, chopped up like meat in a butcher’s shop, ready to be consumed.

In another of her works, Semiotics of the Kitchen (1975), Rosler again takes to the kitchen, this time in the form of a mock cooking show backdrop. In the video, she satirises the social construction of women as homemakers and engages with the absurdity of housewifery by presenting kitchen tools to the viewer in alphabetical order, creating a half cooking show, half children’s show parody. Lauzon describes her character as a “postwar suburban American housewife, part-automaton, part-renegade”. [10] As she works her way through the alphabet, her actions become more and more aggressive, highlighting the rage and frustration of oppressive women’s roles. Rosler reveals the home as a battlefield for the gender politics of the day and it is clear that the semiotics of this kitchen signify fury, resentment and containment.

Characteristic of these two works by Rosler and other feminist work at the time are the assumptions that underlie their critique: the conflation of white, heterosexual, cis, upper middle class housewives with a universal notion of ‘Woman’. As Western culture has become more open to hearing the voices of minorities, second wave feminism has rightly come under fire for its limited, Eurocentric scope, which focused primarily on the experiences of White women. bell hooks argued that for Black women, the home, far from a site of oppression, was traditionally a subversive space for critical consciousness and resistance, a space forged for women who were excluded from second wave feminism and the then patriarchal culture of Black Power.

Carrie Mae Weems began her artistic practice in the wake of the Black activism of the 1960s and 1970s, and in a talk she gave at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, she explained that Kitchen Table Series (1990) was made at the time of great feminist writings, referring specifically to the work of Laura Mulvey (who coined the term ‘male gaze’). Weems stated that work such as this didn’t have space to consider women of colour, and that their experience was not part of the critique. [11] Weems decided to show another way in which the female subject could be portrayed, this time focusing on the experiences of Black women.

The title of the series is of particular relevance since ‘Kitchen Table’ is also the name given to a publishing press formed in 1980 that published work by and about women of colour. One of the founding members, Barbara Smith, said: “We chose our name because the kitchen is the center of the home, the place where women in particular work and communicate with each other. We also wanted to convey the fact that we are a kitchen table, grass roots operation, begun and kept alive by women who cannot rely on inheritances or other benefits of class privilege to do the work we need to do.” [12] Deborah Willis argues in her article ‘Translating Black Power and Beauty’ that the kitchen is symbolic in Weems’ work because while it was the place for cooking and eating, it also housed discussions which fuelled the political work of Black women. [13]

The series consists of multiple tableaux of a young woman (portrayed by Weems) sitting in her kitchen, accompanied by a variety of figures in each photograph. There are almost two dozen photographs in the narrative, which explores a cycle of daily life. It’s important to address the one thing that is consistent among all the photographs in the series: the setting. The audience is let into an intimate space, which contains a table and chairs, a door, vent and a single light, which illuminates each scene from above, acting almost as a spotlight on a domestic stage. The way that the scene is set suggests that there is another chair in the space beyond the picture plane, and that it is the viewer who occupies this seat. This device makes the scene more accessible, since the kitchen is traditionally a place where people are fed and cared for and where conversations take place. By opening up this space to the viewer, Weems presents something very universal and recognisable in one’s own life. In her book Reflections in Black, Willis states that: “The kitchen table is, for many of us, the spiritual place for open discussion.” [14] In presenting this familiar scene to us, Weems attempts to extend this open discussion to the audience, to help investigate themes of history, gender, race, and the way that these combine to form a cultural identity.

One of the photographs shows Weems playing cards with a male partner in a smoke filled kitchen. She references Georges de La Tour’s 1635 painting The Card Sharp with the Ace of Diamonds, which also depicts a game of cards. The setting of Weems’ photograph is similar to the one in the painting, and both grapple with the dichotomy between hidden and

seen, and the power dynamics that this creates. Above her on the wall hangs a poster of Malcolm X, whose gaze is figurally doubled with her own; a reminder of the Black Power movement that Black women had not found a place within. [15] Here Weems subverts the idea of the male gaze, and instead presents an image in which the male figure is in a more vulnerable position, achieved by the framing of the image whereby the viewer can see his hand of cards but not Weems’. The fact that this scene is presented in a kitchen highlights the differing attitudes towards the home; instead of a place where women are trapped, their freedom taken away, in this tableaux Weems presents the power as being on the woman’s side.

While the radical second wave feminist ideal of the abolishment of the kitchen has now faded, it may have left its mark on the architecture of modern homes. Some researchers identify this kitchenless society in the form of an open plan living space which, in opening up the space, has made cooking more collaborative, leaving the image of a housewife alone, trapped in the kitchen in the past. The result of the kitchen’s new identity is perhaps closer to the space of collaboration, discussion and resistance that bell hooks, Deborah Willis and Carrie Mae Weems spoke of. Martha Rosler continued to respond to images of the home in her art, but instead employed it to critique the housing and homelessness crisis in North America, and then the Vietnam War in the series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (1967-72). While many of the concerns dealt with by this generation of artists are still discussed, feminism and feminist artists moved to incorporate concerns about race, class, privilege, and gender identity and fluidity, creating a new movement of more intersectional feminist art.

Shockingly, some feminists like to cook! After some of the radicalism of second wave feminism subsided, feminists wrote about reforming the act of cooking to align with their beliefs. Men were encouraged to cook, vegetarianism was endorsed, food co-operatives were founded and women chefs were supported. There was also a rise in feminist cookbooks. In 1983 a lesbian feminist group, the Cincinnati Lesbian Activist Bureau, published a cookbook called Whoever Said Dykes Can’t Cook? As well as raising funds for the group it also aimed to prove than lesbian feminists cooked, AND ENJOYED IT.

I for one love to cook. And bake. And dance around the kitchen using my wooden spoon as a microphone. I also love doing these things for the people I love (maybe excluding the dancing; no one needs to see that…). Sitting around the kitchen, sharing food and chatting with people who make me happy is one of the simplest forms of joy, and I’m glad I don’t have to question my position as a feminist when I experience that joy.

Grannie’s wooden spoon has now been retired, and instead sits proudly on top of my chest of draws, a reminder of the queen that she was, and the cakes she made. Perhaps it’s time to dust it off and whip up a batch of her famous chocolate cake.

Notes: 1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15. ‘“I’m Not a Feminist… I Love Cooking!” Why Food Is a Feminist Issue’, Feminist Current (blog), 4 January 2015, https://www.feministcurrent.com/2015/01/04/im-not-a-femini st-i-love-cooking-why-food-is-a-feminist-issue/. Debbie Kemmer, ‘Tradition and Change in Domestic Roles and Food Preparation’, Sociology 34, no. 2 (2000) p. 324 Suzanne M. Bianchi et al., ‘Is Anyone Doing the Housework? Trends in the Gender Division of Household Labor’, Social Forces 79, no. 1 (2000) p. 201 Stacy J. Williams, ‘A Feminist Guide to Cooking’, Contexts 13, no. 3 (2014) p. 59 Ann Oakley, The Sociology of Housework (Policy Press, 2018). Rosie Boycott, ‘Why a Woman’s Place Is in the Kitchen’, The Guardian, 26 April 2007, sec. World news, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/apr/26/gender.lifea ndhealth. Claudette Lauzon, ‘An Unhomely Genealogy of Contemporary Art’, in The Unmaking of Home in Contemporary Art (University of Toronto Press, 2017) p. 33 Lucy Lippard, ‘Household Images in Art’, in The Pink Glass Swan: Selected Feminist Essays on Art (New York, 1995). Elizabeth Richards, ‘Materializing Blame: Martha Rosler and Mary Kelly’, Woman’s Art Journal 33, no. 2 (2012) p. 9 Lauzon, ‘An Unhomely Genealogy of Contemporary Art’ p. 37 National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., Carrie Mae Weems: Kitchen Table Series, 2018. Elizabeth Pérez, Religion in the Kitchen: Cooking, Talking, and the Making of Black Atlantic Traditions (NYU Press, 2016), p. 111 Deborah Willis, ‘Translating Black Power and Beauty - Carrie Mae Weems’, Callaloo 35, no. 4 (2012) p. 994 Deborah Willis, Reflections in Black: A History of Black Photographers, 1840 to the Present (W.W. Norton, 2002) pp. 183-4 Claire Raymond, Women Photographers and Feminist Aesthetics / Claire Raymond. (New York : Routledge, 2017) p. 148