5 minute read

Overlooked Britain London’s grand circle, the

Overlooked Britain The M25 – London’s grand circle

lucinda lambton Next time you’re stuck on the motorway, rejoice in the necklace of jewels strung around the capital

Advertisement

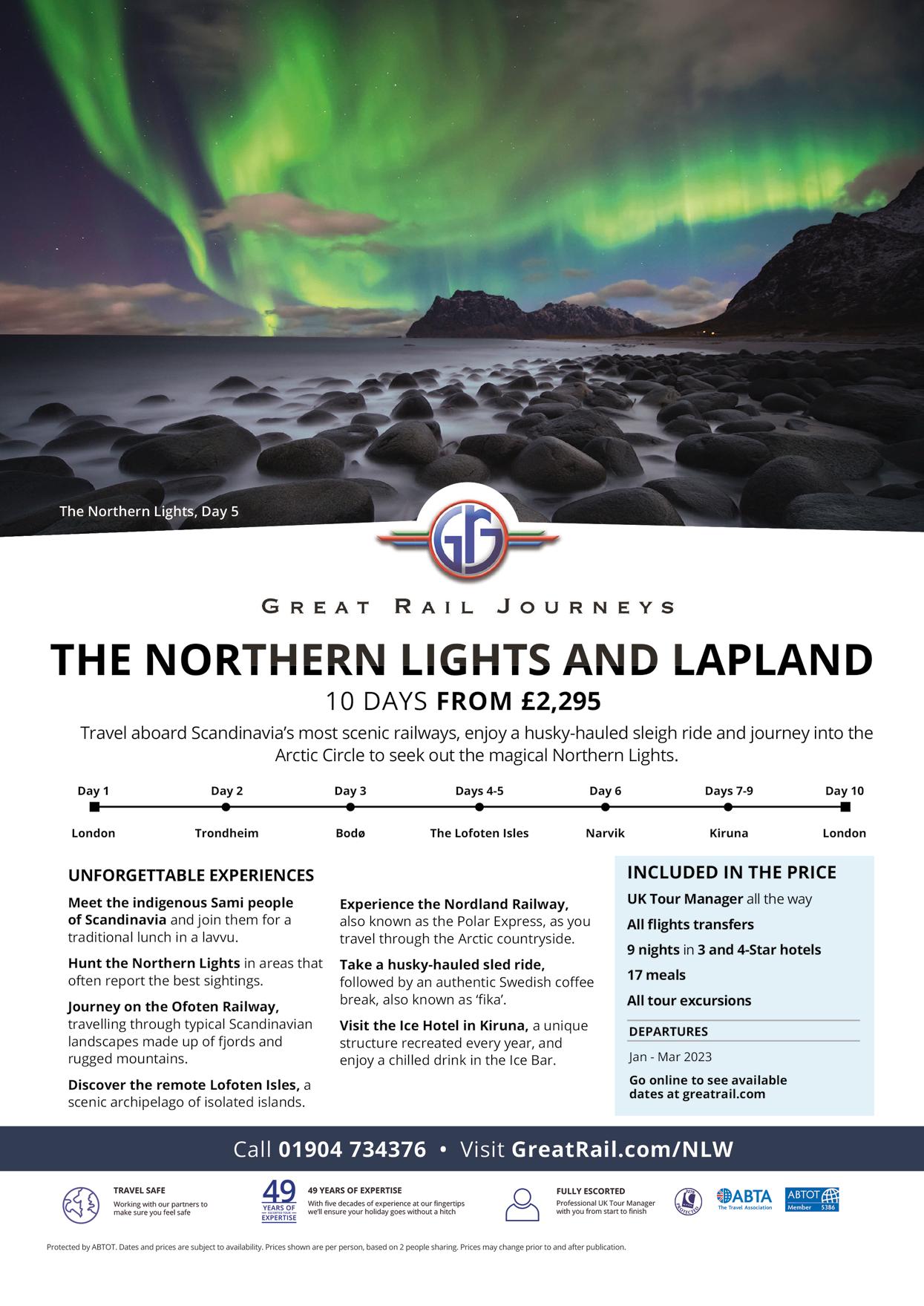

Egham’s Loire château: Royal Holloway College (1886), Surrey, by William Henry Crossland, inspired by the Château de Chambord

‘There is a necklace of jewels that is strung around London – otherwise known as the M25.’

BRAVO! I wrote that sentence many years ago and can proudly say that I have not written a better one since.

That motorway, which causes such mayhem and misery to so many, is surrounded by a wealth of historical and architectural diversions.

At Egham in Surrey, a profusion of pinnacled and pepperpotted spires and towers rears into the sky, along with domes, fanciful chimneys and finials, soaring ebulliently from the trees, giving the M25 a quite stupendous skyline. It is Royal Holloway College, a gargantuan château of Portland stone and ‘flaming red brick’. According to one contemporary ardent admirer, it ‘fairly scorched the eye’ when it was built between 1879 and 1887 by William Crossland for Thomas Holloway.

When one is faced with its vivid vastness, there seems to be no other building as bright and as big – 550 feet by 376 feet – in the whole wide world. Designed to attract the attention of the passing public on the railways, it reigns triumphant over the speeding motorway.

Thomas Holloway, ‘one of the wonders of the 19th century’, made millions with his ‘healing genius’ for inventing all-purpose pills and ointments. So all-purpose were his remedies that one Irish farmer claimed not only to have regained the use of all his limbs, his sight and his hearing but also to have been relieved from pains that had plagued him for 20 years.

Holloway’s genius in fact lay in his rhetoric rather than in the effectiveness of his remedies. He became a philanthropist, always claiming to have worked harder spending his money than in making it.

Nearby there is yet further endorsement of his excellence with the Holloway Sanatorium. It was built as a hospital for ‘the insane of the middle classes … and with grounds … equal to those at the Crystal Palace’. Today, it has transmogrified into an ‘exclusive housing development’. Gridlocked motorists should give three hearty cheers nevertheless for the preservation of its Franco-Flemish, Gothic forms, crowstepped gables and great tower, modelled on the Cloth Hall at Ypres.

Eight miles to the south, near Cobham, we find Silvermere Haven, a pet cemetery with many hundreds of melancholy epitaphs. There are tombs for the two rats Gladstone and Disraeli. And what sad delight to see ‘Gone for Long Walkies’ emblazoned on a gravestone.

A mere mile from here across the fields at Chaldon in Surrey, between exits 6 and 7, lies the late-12th- and early-13th-century church of St Peter and St Paul. Reaching it by a narrow-as-yourcar road, which presents a particularly rural picture, we find its little flint body and wooden spire.

Above: Plan for Copt Hall, Essex, drawn in 1735. Left: Temple Bar in Theobalds Park, Hertfordshire, 1926. It was returned to London in 2003

It shelters the rarest wall painting in Europe, dating from 1200 and painted in the subtlest of colours. It depicts some of the most gruesome scenes imaginable. The Last Judgement is as grisly as it is glorious. Little naked bodies fearfully climb up the Ladder of Salvation through Hell and Purgatory to Christ amidst the clouds on high. Lust is represented by a man and a woman being embraced by the devil. Envy is a bald-pated figure longing for another’s lustrous locks.

Sweeping over the elegant lines of the Dartford Bridge, I am drawn down the Thames to Gravesend – where Pocahontas lies buried. She was my seven-times-great-grandmother and it was thanks to her support in the early17th century that the early English settlers in America were able to survive. Woe betide the Disney version today!

As you speed round the full circle of the M25, hoot a salute to honour those buried on either side. Delius the composer, as well as his champion Sir Thomas Beecham and the pianist Eileen Joyce are buried in St Peter’s Churchyard at Limpsfield, Surrey.

Nearby, at West Horsley, ponder the remains of the executed Sir Walter Raleigh’s head, which lies beneath the floor of St Mary’s Church. When his body was buried in St Margaret’s, Westminster, his desolate wife had his head embalmed and kept it with her – in a red leather bag – until the day she died.

St Michael’s Church in St Albans harbours the remains of Sir Francis Bacon, the philosopher whose wisdom, it was said, ‘was too far advanced of the time to be palatable’.

It was this very advanced wisdom that brought about his demise in 1626: determined on experimenting with his notion of freezing food, he scrabbled about in the snow on Highgate Hill with a chicken carcass and caught a chill, then perished from bronchitis.

According to legend, King Harold (as in the Battle of Hastings) is buried at Waltham Abbey, Essex. A royal connection of a harrowing kind lingers among the ruins of the Dominican priory at Kings Langley in Hertfordshire. Piers Gaveston, Earl of Cornwall, lies there. It was thanks to his doubtful connection with Edward II that in 1327 the King was hideously done to death with a red-hot poker at Berkeley Castle, Gloucestershire. It was said that his screams were audible two miles away.

A far happier, peacefully perfect spot is the little Quaker meeting house at Jordans, the burial place of William Penn, august Quaker and founder of Pennsylvania. When the apple trees are in full blossom and the greensward glints in this cosily English scene, it is strange indeed to think of the American memorial to the man, which has perched high on the dome of Philadelphia’s City Hall since the 1890s.

Death’s roll-call around the M25 never ends. The remains of Anthony Hope, author of The Prisoner of Zenda, lie at Leatherhead. Those of Martin Secker – founder of Secker and Warburg, the first publishers of D H Lawrence – lie in Iver, Buckinghamshire. Most imposing of all is Wyatt’s monument to the poet Thomas Gray at Stoke Poges nearby.

Two of the grandest and greatest of all these wonders have included – temporarily, from 1880 until 2003, when it was returned to its original City of London location – the Temple Bar Gatehouse, designed by Sir Christopher Wren in 1672, and Copt Hall, whose late-19th-century gardens once swept into the Essex countryside. A Tudor house stood proud on this spot, where – joy of joys – A Midsummer Night’s Dream was first performed.

Next time you’re trapped in the motorway traffic on the M25, hold hard and remember the glories strung about it – a dazzling necklace of jewels indeed.