My crush on Peter Cook

The strongest link – Anne Robinson’s family holiday in Marbella England can win – Gary Lineker on the World Cup The genius of Dolly Parton – Robert Bathurst by his co-star Madeline Smith

December 2022 | £4.95 £4.13 to subscribers | www.theoldie.co.uk | Issue 420 32-PAGE OLDIE REVIEW OF BOOKS RONALD BLYTHE AT 100 ‘ is an incredible magazine – perhaps the best magazine in the world’ Graydon Carter

12

Features

12 Modern Life: What is generative artificial intelligence? Richard Godwin 25 Mary Killen’s Fashion Tips 33 My gender-fluid mate Sir Les Patterson 40 History David Horspool 42 Town Mouse Tom Hodgkinson

43

46

51

52

54

54

66

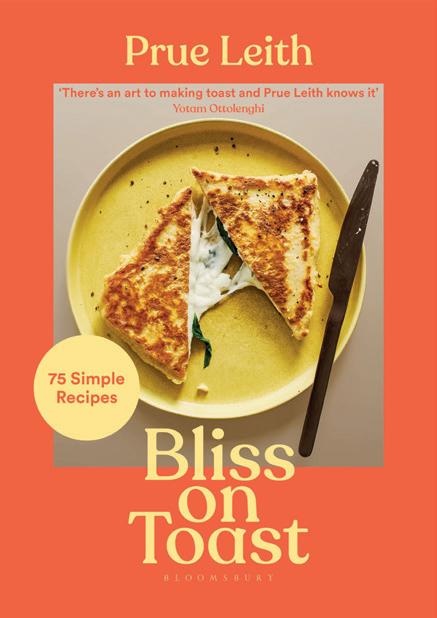

Commonplace Corner

56 My Sporting Life: Memories, Moments and Declarations, by Michael Parkinson Jasper Rees 57 Edda Mussolini: The Most Dangerous Woman in Europe, by Caroline Moorehead Annabel Barber 59 The Posthumous Papers of the Manuscripts Club, by Christopher de Hamel Christopher Howse 61 Come Back in September, by Darryl Pinckney Frances Wilson 61 A Brief History of Pasta, by Luca Cesari and Johanna Bishop Elisabeth Luard 63 Bournville, by Jonathan Coe Nicholas Lezard 65 Rock Concert: A HighVoltage History, from Elvis to Live Aid, by Marc Myers David Hepworth 66 Just Passing Through, by Milton Gendel and Cullen Murphy Nicky Haslam Arts

70 Film: Triangle of Sadness Harry Mount 71 Theatre: My Neighbour Totoro William Cook

71 Radio Valerie Grove 72 Television Frances Wilson 73 Music Richard Osborne 74 Golden Oldies Rachel Johnson 75 Exhibitions Huon Mallalieu

Pursuits

77 Gardening David Wheeler

Supplements editor

Liz Anderson

Amelia Milne

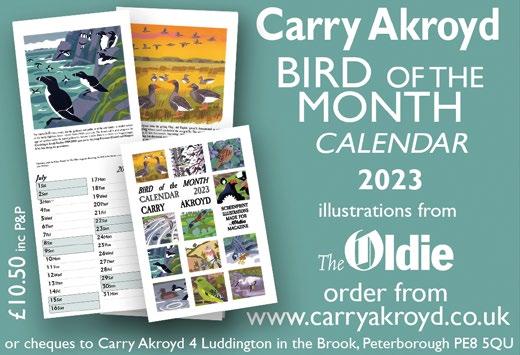

Kitchen Garden Simon Courtauld 78 Cookery Elisabeth Luard 78 Restaurants James Pembroke 79 Drink Bill Knott 80 Sport Jim White 80 Motoring Alan Judd 82 Digital Life Matthew Webster 82 Money Matters Margaret Dibben 85 Bird of the Month: Avocet John McEwen

77

90

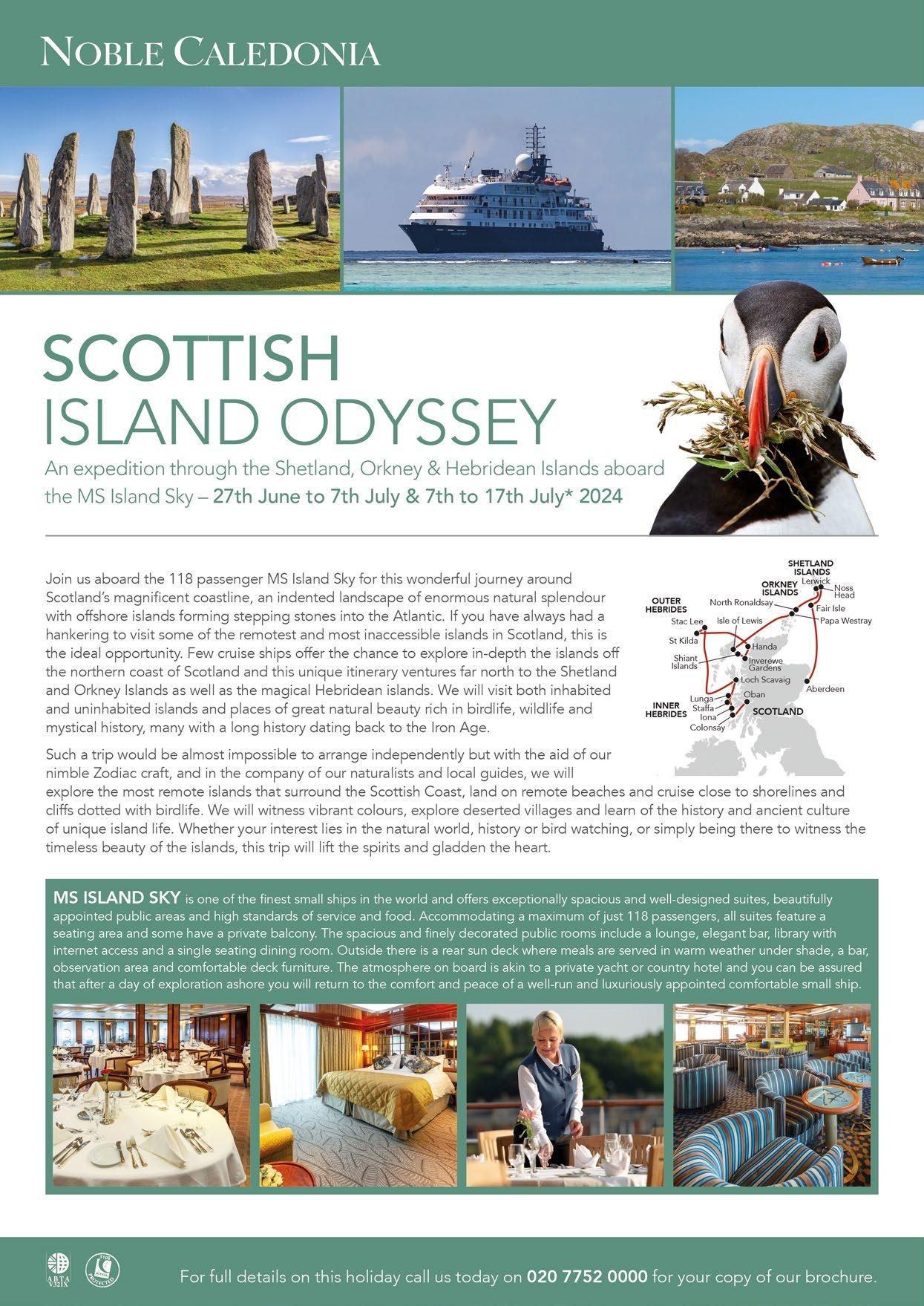

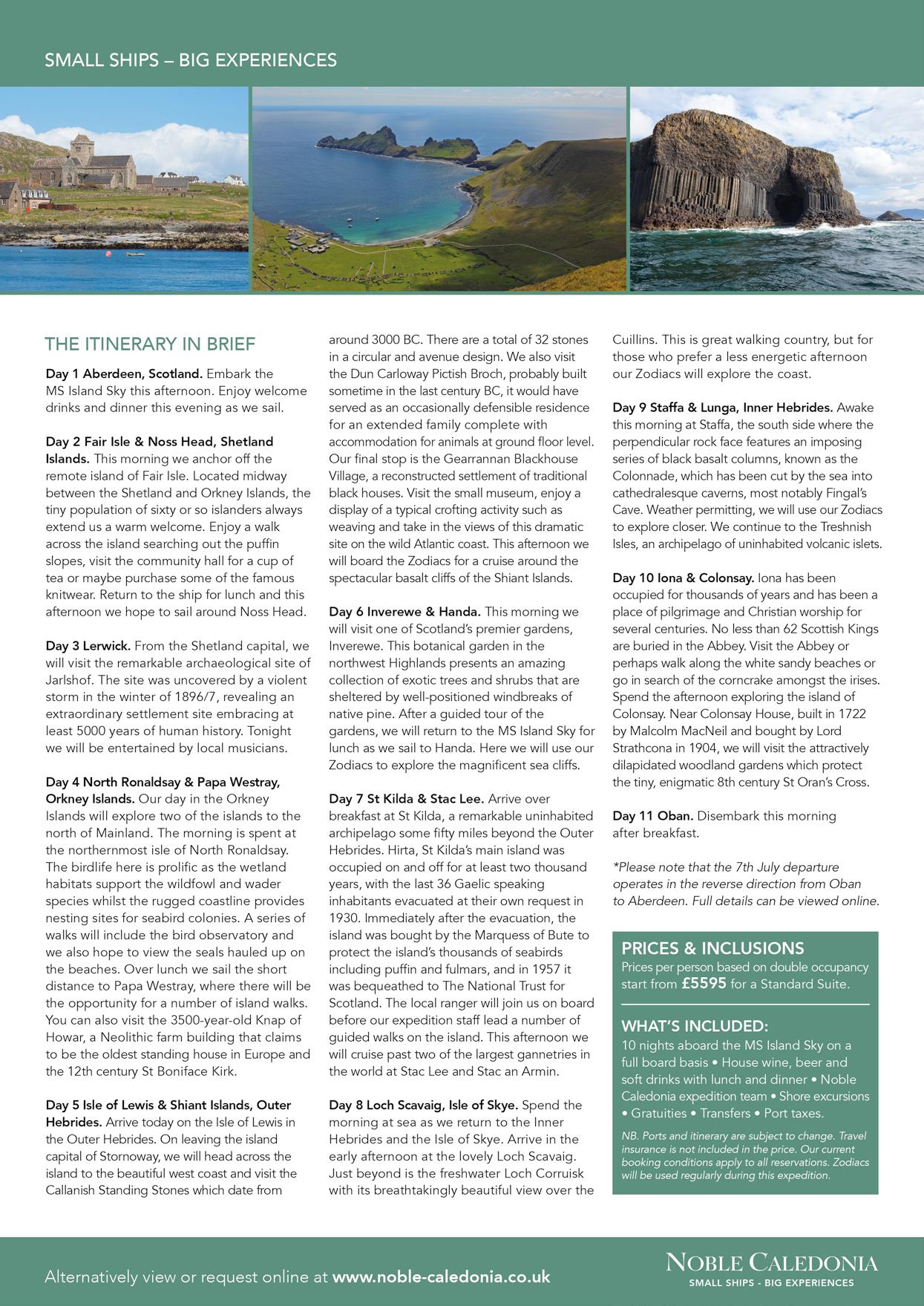

The Marbella Club Anne Robinson and Emma Wilson

On the Road: Gary Lineker Louise Flind

Taking a Walk: Cairngorms Two Lochs Trail Patrick Barkham

For display, contact : Paul Pryde on 020 3859 7095 or Rafe Thornhill on 020 3859 7093

For classified: Jasper Gibbons 020 3859 7096 News-stand enquiries mark.jones@newstrademarketing.co.uk

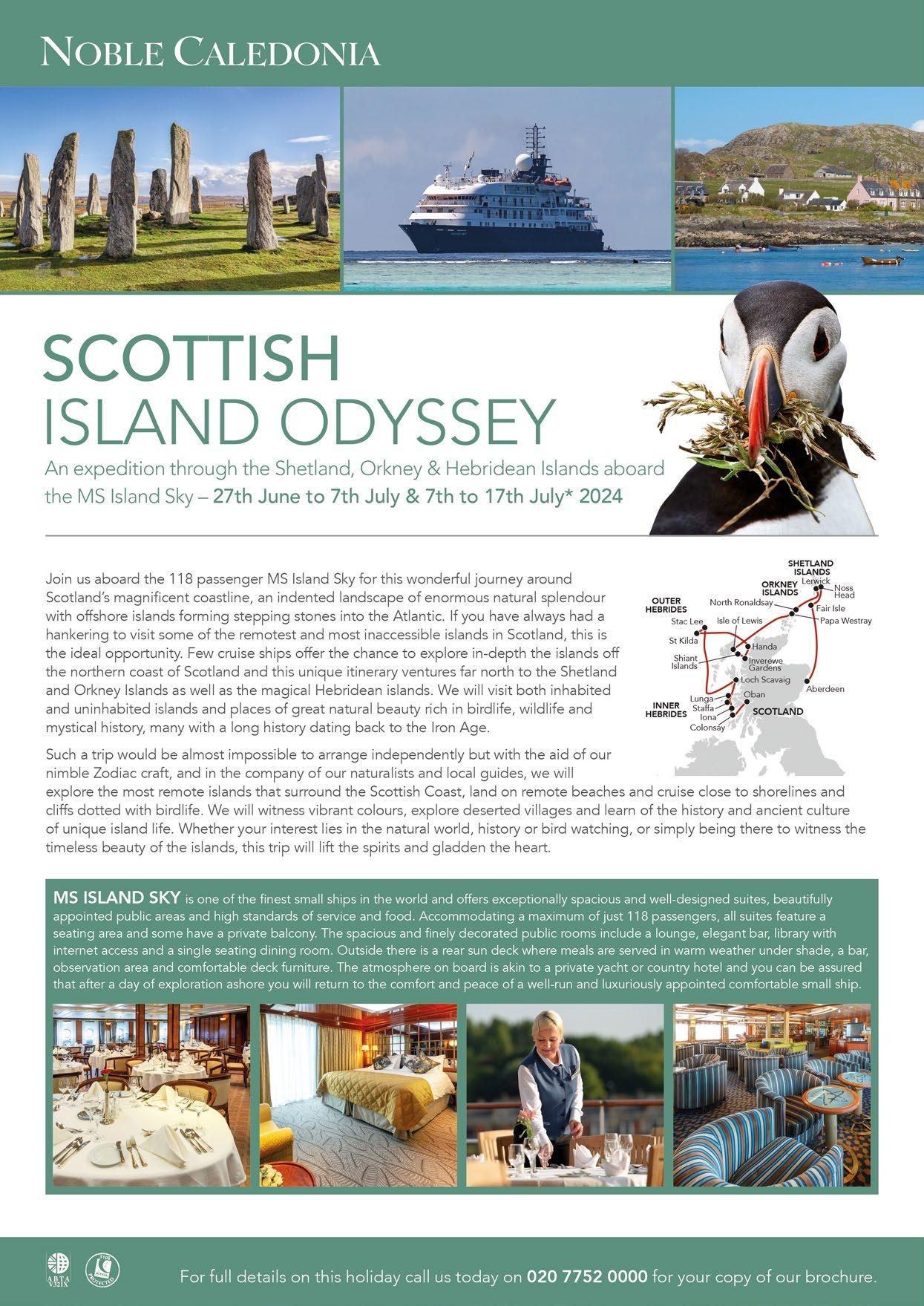

Front cover Peter Cook in Beyond the Fringe, 1962. Friedman-Abeles

The Oldie December 2022 3

67

67

68

93

95

95

13 Playing golf with Peter Cook Madeline Smith 14 The hit film Genevieve’s 70th birthday Andrew Roberts 16 Huntley & Palmer turns 200 Mark Palmer 18 Poems soothed my grief Rachel Kelly 20 My school friend the IRA terrorist Virginia Ironside 26 Smyrna, joy of Asia Philip Mansel 29 An oldie’s love for her mobile phone Caroline Flint 30 Winter is coming Ronald Blythe 32 Not the retiring type Andrew Cunningham 31 Most obscure clubs in the world Jonathan Sale 34 Peter Beard, snappy playboy Anthony Haden-Guest 37 When Dolly Parton met Dickens Robert Bathurst Regulars 5 The Old Un’s Notes 9 Gyles Brandreth’s Diary 10 Grumpy Oldie Man Matthew Norman 102

Olden Life: What was a British Visitor’s Passport? Liz Treacher

Country Mouse Giles Wood 45 Postcards from the Edge Mary Kenny

Small World Jem Clarke 49 School Days Sophia Waugh 49 Quite Interesting Things about ... the Olympics John Lloyd 50 God Sister Teresa 50 Memorial Service: Lord Sainsbury KG James Hughes-Onslow

The Doctor’s Surgery Theodore Dalrymple

Readers’ Letters

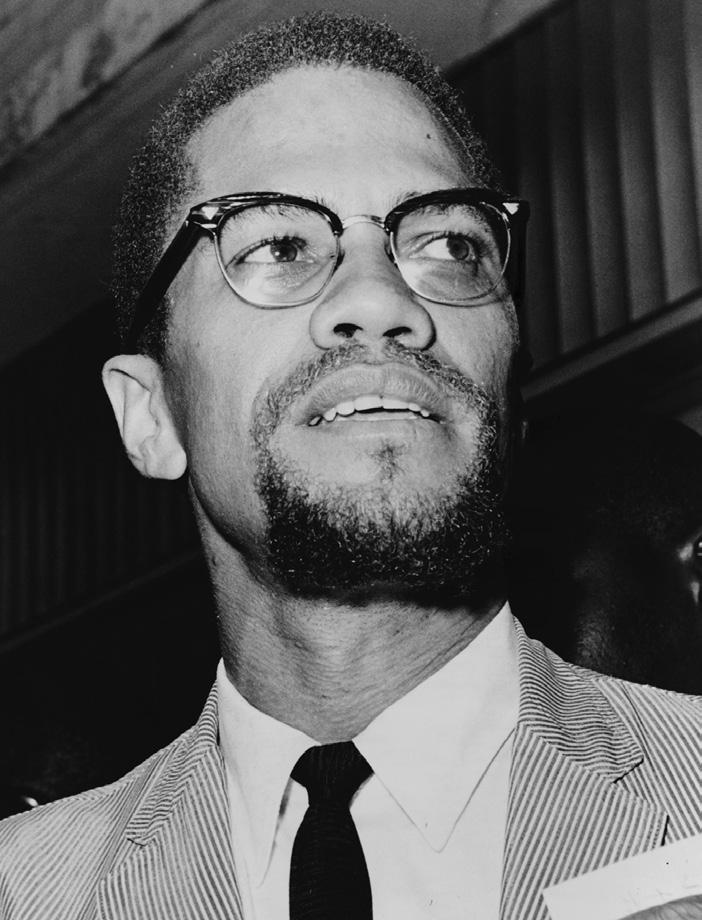

I Once Met… Malcolm X Patrick Hickman-Robertson

Memory Lane Bernard Hillon

History David Horspool

Rant: Loo-paper dispensers Carolyn Whitehead

Media Matters Stephen Glover

Crossword

Bridge Andrew Robson

Competition Tessa Castro

Ask Virginia Ironside

Books

Editorial assistant

Publisher

Patron saints

At large

Our

David

Oldie subscriptions

To

Moray House, 23/31 Great Titchfield Street, London W1W 7PA www.theoldie.co.uk new order, please visit our

Editor Harry Mount Sub-editor Penny Phillips Art editor Jonathan Anstee

James Pembroke

Jeremy Lewis, Barry Cryer

Richard Beatty

Old Master

Kowitz

●

place a

website subscribe.theoldie.co.uk ● To renew a subscription, please visit myaccount.theoldie.co.uk ● If you have any queries, please email help@subscribe.theoldie.co.uk, or phone 0330 333 0195, or write to Oldie Subscriptions, Rockwood House, 9-16 Perrymount

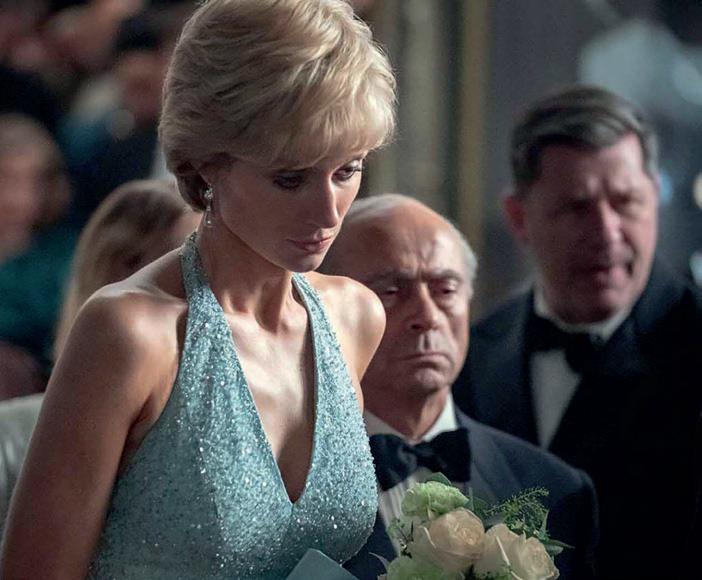

Road, Haywards Heath,West Sussex RH16 3DH

Advertising

88

91

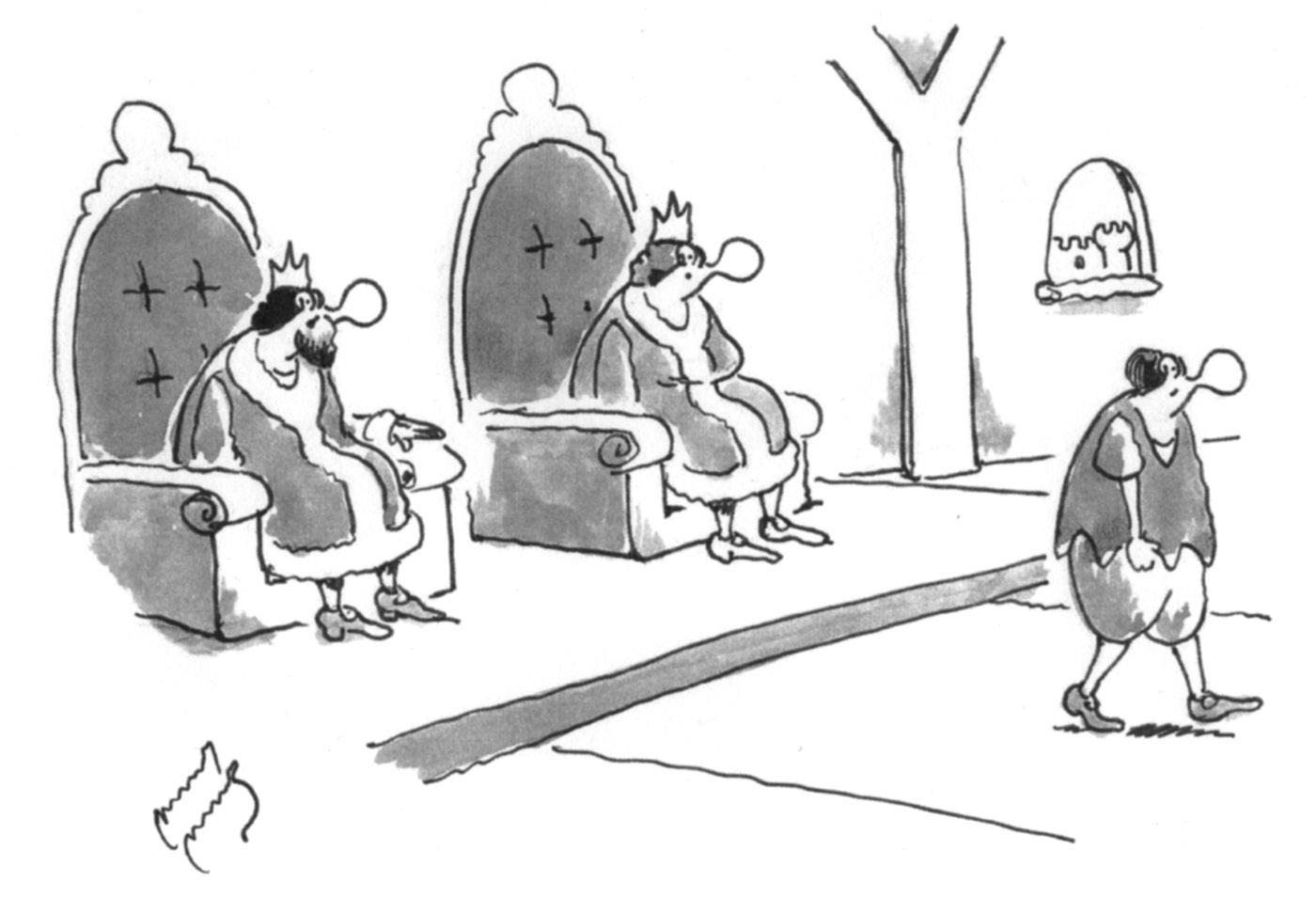

Reader Trip Come and stay at Château Beychevelle p83 ABC circulation figure July-December 2021: 48,249 Subs Emailqueries?help@ subscribe. theoldie. co.uk Genevieve hits 70 page 14 200-year-old biscuits page 16 Hello, Dolly! page 37 Give from £2 an issue See page 11 NB: Don't throw away your free 2023 calendar, included with this issue! 2023 CARTOON CALENDAR‘He’sbringing withhim... nasty,brutish short you’lllikehim’

Travel

86

Overlooked Britain: Hedgerley, Buckinghamshire Lucinda Lambton

The Old Un’s Notes

Theatregoers who are keen on Dickens face a joyful December.

Almost wherever one looks, A Christmas Carol is being staged – not least Dolly Parton’s Smoky Mountain Christmas Carol, which the show’s star, Robert Bathurst, writes about on page 37 of this issue.

The Royal Shakespeare Company is doing A Christmas Carol in Stratfordupon-Avon. London’s Old Vic is doing a production. And Deborah Warner has scheduled it at the Ustinov Theatre in Bath. Sir Nicholas Hytner has recruited Simon Russell Beale for a version at his Bridge Theatre.

Further adaptations are to be had this year in Kingston upon Thames, Windsor, Bristol, Doncaster, Coventry, Exmouth, Chesterfield, Woking, Portsmouth, Wilmslow, Salisbury, Crewe, Liverpool, Bolton and Buxton and at Sheffield Cathedral.

Until a decade ago, Dickens’s tale of redistribution was seldom

known on stage. Since then, it has become the second-most popular Christmas tale – after Matthew, Mark, Luke and John’s greatest Christmas story of all.

On the subject of Charles Dickens, few people realise he was a keen punter at betting shops.

He turned against them in June 1852, when he placed half a crown on a well-fancied horse, Tophana, in the Western Handicap, at odds of 2/1. He was ripped off by the welshing bookie, known to him as Mr Cheerful.

The horse won, but when Dickens went to collect his

seven-and-sixpence winnings, he ‘returned to Mr Cheerful’s establishment and found it in great confusion’, with Mr C nowhere to be seen and a minion explaining he had gone ‘to a sale a’ Monday’.

Dickens concluded that ‘Mr Cheerful has been so long detained at the sale, that he has never come back.’

As a result of Dickens, and many others, experiencing such scandalous customer service, towards the end of 1853 – on 1st December –bookmakers were officially and legally outlawed.

It wasn’t until over a century later, in May 1961, that they were legalised.

Among this month’s contributors

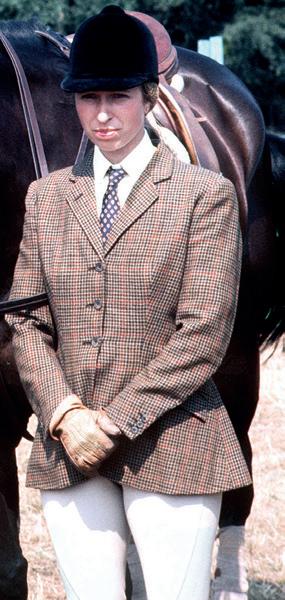

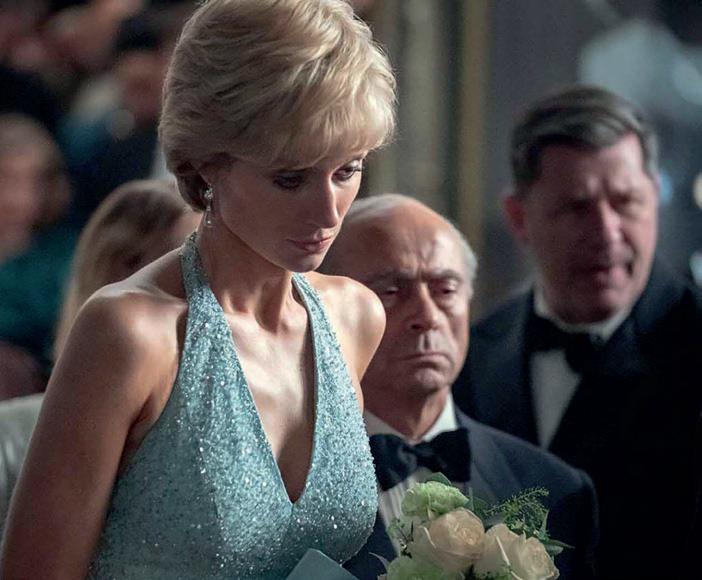

Madeline Smith (p13) played Miss Caruso, the Bond Girl in Live and Let Die who has her dress unzipped by Roger Moore with a magnetic watch. A Hammer horror star, she was also in Up Pompeii.

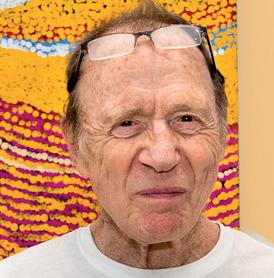

Ronald Blythe (p30) is our greatest living rural writer. He turned 100 on 6th November. He is author of Akenfield and Word from Wormingford: A Parish Year. His new book is Next to Nature.

Anthony Haden-Guest (p34) lives in New York and is the model for Peter Fallow in Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities. He wrote The Last Party: Studio 54, Disco, and the Culture of the Night

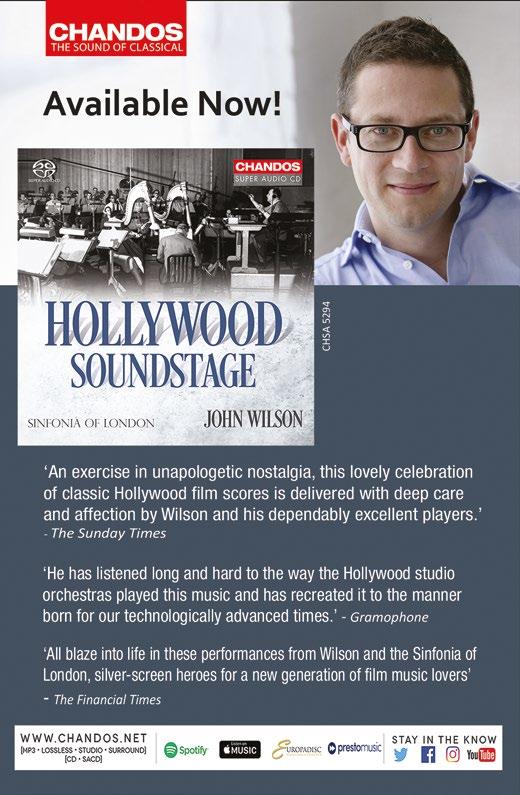

David Hepworth (p65) presented Live Aid and The Old Grey Whistle Test. He is author of Abbey Road Studios at 90. He presents the Word in Your Ear music podcast with Mark Ellen.

Happy 130th birthday, Bertie Wooster!

Jeeves’s comic genius of a boss, Bertram Wilberforce Wooster, is never given a precise birthday by P G Wodehouse.

But he is said to be 24 in Jeeves Takes Charge, first published in November 1916. So it isn’t fanciful to suggest he was born in November 1892, 130 years ago this month.

Bertie went to Eton and Magdalen College, Oxford, before embarking on his not-very-arduous grown-up life.

The late Dr Angus Macintyre (1935-94), a much-loved history don at Magdalen and father of the writer Ben Macintyre, tried and failed to get Bertie included in the Magdalen College Record – which lists the achievements of Magdalen undergraduates and graduates.

Surely, on his 130th

The Oldie December 2022 5

NEIL SPENCE

Happy 130th birthday, Bertie!

Michael Caine’s Scrooge

Important stories you may have missed

birthday, it’s time to include Bertie, the greatest nonachiever in history, in the Record.

Drunken

Empty canoe retrieved by police Orcadian

£15 for published contributions

NEXT ISSUE

The January issue is on sale on 14th December 2022.

GET THE OLDIE APP

Go to App Store or Google Play Store. Search for Oldie Magazine and then pay for app.

OLDIE BOOKS

The Very Best of The Oldie Cartoons, The Oldie Annual 2023 and other Oldie books are available at: www.theoldie.co.uk/ readers-corner/shop Free p&p.

OLDIE NEWSLETTER

Go to the Oldie website; put your email address in the red SIGN UP box.

HOLIDAY WITH THE OLDIE Go to www.theoldie.co. uk/courses-tours

75 years on – royal wedding

20th November would have been the 75th wedding anniversary of the late Queen and the late Prince Philip.

To commemorate the anniversary, Tessa Dunlop has written Elizabeth and Philip: A Story of Young Love, Marriage and Monarchy, out now.

In the book, Dunlop writes that 1947, the year of the royal wedding, saw a peacetime record of 401,201 couples tie the knot.

Barbara Weatherill, 97, pre-empted the future

Queen’s November wedding by a matter of months; she married airman Stan in July 1947. She says, ‘Our parents knew each other. That was very common in those days. Stan asked my father’s permission before he asked me!’

Barbara remembers a hit song of the time, People Will Say We’re in Love. Barbara says, ‘And I was! There were a lot of us in love at that time. I don’t think it necessarily was Elizabeth and Philip’s favourite song, but it was played on the radio a lot.’ 100-year-old Philip Jarman began courting Cora, a Bletchley Park veteran, in 1947. He remembers, ‘Us lot who went through the war looked at things differently. We felt lucky to be alive and

we wanted to crack on with life. So, yes, we did get married young.’

The average age of the blushing bride fell to an all-time low of 22. Philip Jarman remembers that, after the war, ‘A girl still belonged to her father. How can I put it? You couldn’t do much unless you were married! We took marriage seriously. It was difficult to get divorced, and considered shameful.’

Philip and Cora were together for 72 years, one year shy of Elizabeth and Philip’s union. ‘I miss Cora very much. She was a great royalist. Back then, monarchy and marriage really meant something.’

On the subject of long marriages, Conversations from a Long Marriage by Jan Etherington was published on 3rd November.

The characters in the book, based on the Radio 4 series of the same name, have been married for over 40 years. Children of the sixties, they’re still free spirits, even if being spontaneous requires rather more planning these days.

Their conversation will be familiar to many oldies. It features dodgy knees, resentment of new glasses and difficulties with stairs: ‘Hey, baby, fire up the Stannah. We’re taking a stairlift to heaven.’

6 The Oldie December 2022 KATHRYN LAMB

Man ‘hid three snakes in pants’ i

barber tried to break into car Dundee Courier

‘Drinking alone is going to be a lot more lonely’

‘They’re known locally as the railway children’

For over 30 years, Jan Etherington has been writing radio and TV comedy series with her husband (of almost 40 years) and writing partner, Gavin Petrie. Conversations from a Long Marriage was her first solo narrative comedy. It has just been commissioned for a fourth radio series.

Joanna Lumley and ‘husband’ Roger Allam act the principal roles. When Joanna Lumley first read the script of the comedy, she told Jan Etherington, ‘It’s as if you’ve been eavesdropping at my window!’

On 5th November 2022, Sir Sydney Kentridge KC celebrated his 100th birthday.

Kentridge is a man who can be talked of only in superlatives: he has been

described by many as the greatest advocate of the 20th century. His friend and colleague Jonathan Sumption described him as ‘the barrister’s barrister, with a moral stature that no amount of forensic technique can impersonate.’

After war service in East Africa and Italy, Kentridge started practice in his native South Africa in 1949. He swiftly became the dominant advocate at the Johannesburg Bar, representing Nelson and Winnie Mandela, Desmond Tutu and ANC President Chief Albert Luthuli, among many others.

He achieved international fame in 1977 for his representation of the family of Steve Biko during the inquest into Biko’s death at the hands of the police. Kentridge would be portrayed by Albert Finney in the play that was staged of the inquest.

In the 1980s, Kentridge shifted his practice to London and became the leading QC in England, where he defended P&O in the Herald of Free Enterprise manslaughter prosecution and represented the Countryside Alliance in its challenge to the FoxHunting Bill.

He argued (and won) his last case in the Supreme Court in 2013 at the age of 90. His career as an advocate in full-time practice lasted exactly 64 years, perhaps the longest in legal history.

This year, a new book, Thomas Grant’s The Mandela Brief: Sydney Kentridge and the Trials of Apartheid, celebrated his most famous trial. It features on page 7 of the Oldie Review of Books in this issue.

As she turns 70, Alexandra Pringle, editor-in-chief of Bloomsbury Publishing for over 20 years, and three pals – all editors and writers – have set up a new company, Silk Road Slippers.

The aim is to sell ‘beautiful pieces from antique lands’,Mandela’s lawyer: Sir Sydney

including kaftans, Indian jewellery, Peruvian silver and Mexican pots, hunted down in market alleyways and souks.

Pringle comes from the Afriats, a family of Berber Jewish traders whose caravans travelled from Timbuktu to Mogador with gum arabic, ostrich feathers and spices. The Silk Road Slippers logo is her family trademark from the 1920s, when the Afriats brought indigo from Pondicherry and cotton from Manchester to make cloth for the Tuareg, the blue men of the Sahara.

‘I feel I’m reverting to my roots!’ Pringle says, ‘All the time I was stuck to my desk at work, doing a job I was passionate about, I promised myself that the moment I

retired, I would take off and travel to my heart’s content.’

The moral is you’re never too old to hit the Silk Road!

The Barbican’s family show for Christmas is My Neighbour Totoro, a charming tale about two little girls who discover a benevolent woodland monster (reviewed on page 71).

The furry beast has a friend who is a cat-bus, which the Barbican’s production depicts with a vast, inflatable puppet. Reviews have been generally positive but none, curiously, mentioned that the blow-up puppet of the cat-bus is decidedly male.

There is no easy way to say this, but it has two prominent testicles. Don’t look, children!

The Oldie December 2022 7

‘It’s the first time the bank has been any help to me’

‘Eddie, take everything out of fear and put it into greed’

‘Of course he’s a good listener. I had his tongue cut out’

My royal appointments diary

For over 50 years, I’ve recorded my gripping meetings with the Queen

‘Keep a diary and someday it’ll keep you.’

Whoever said it – Mae West used the line in a film in 1937, but both Margot Asquith and Lillie Langtry were reported as saying it in the 1920s – was bang on the money. I started keeping a diary in 1959 (when I was eleven) and I have been profitably mining it almost ever since.

It’s because I keep a diary that I can tell you that I first met Queen Elizabeth II on the evening of Thursday 2nd May 1968. I was a 20-year-old student at Oxford at the time and Her Majesty, 42, came to visit the university debating society, the Oxford Union.

When she had gone, I reprimanded William Waldegrave (the Union President, now Baron Waldegrave of North Hill and Provost of Eton) for not carrying the monarch’s umbrella for her as he escorted her across the courtyard in the rain.

He told me, ‘The Queen insists on holding her own umbrella – always. If someone else holds it, the rain trickles down her neck.’

Over the years, by chance and by design, I was lucky enough to have scores of encounters with our late Queen. I kept a record of them all in my diary.

She was a very special person (very funny, too) and since her death on 8th September I have been working 15-hour days (literally) using my old diary entries as the basis for what I hope will be a different kind of book about her.

Elizabeth: An Intimate Portrait is coming out on 8th December. I am with the same publishing house as Prince Harry, whose book is out in January. I am grateful to them for letting me get ahead of the game.

My wife regularly tells me that what my life has always lacked is ‘career development’. She claims that what I am doing now is exactly what I was doing when we first met – on 6th June 1968, five weeks to the day after that first meeting with Her Majesty. Leafing through my diary, I see she is right.

I have just found my entry for Thursday 31st December 1970: ‘Time for my end-of-year review. It is six months since I left Oxford. What has been achieved?’

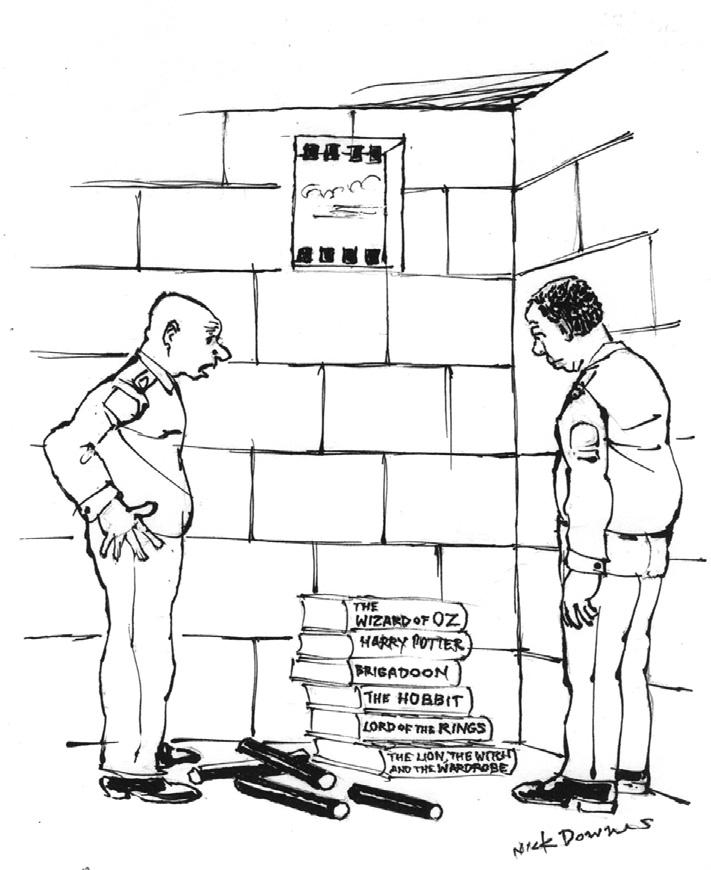

Then as now, I was writing a book. It wasn’t about Her Majesty, but about those entertained at her pleasure. It was a serious book about prison reform.

‘Some worthwhile visits,’ I recorded. ‘HM Prison Bristol, HM Prison Grendon, Lowdham Grange Borstal, HM Prison Liverpool, HM Prison Holloway.

‘No easy answers. Indeed, whatever the conditions of the prison, the level of recidivism remains much the same. Horrific conditions aren’t a deterrent: most prisoners are “present dwellers”: when they commit an offence, they are not thinking about the possible outcome.

‘Good conditions are more civilised but don’t, of themselves, improve the inmates’ chances. Only education and training for work and life can do that.’

Half a century on, there’s nothing new there.

Again, then as now, I was working in TV and radio. I had fronted a couple of documentaries and, according to the diary, ‘had meetings galore – Robin Scott (né Scutt, Controller, BBC2), Edward Barnes and Monica Sims (Children’s Department – boy, do we take ourselves seriously!) … All talk, leading to more talk.’

Half a century later, I am still going to meetings that go nowhere. In the interim, I have learnt that if the person you are meeting has the word ‘development’ attached to them, there won’t be any.

My 1970 report on the radio front was more positive. ‘I like Tony Whitby, Controller, Radio 4. I think that meeting will lead somewhere. I like Con Mahoney, Head of Light Entertainment, Radio. I like the people I bump into in his office – eg Ted Ray and Arthur Askey.

‘I like the producer he has given me, Peter Titheradge – full of old-world courtesy AND the son of the great Madge Titheradge. She was a great beauty, a famous Peter Pan – and a childhood friend of Noël Coward.’

Happily, I am still popping up on the radio in the 2020s much as I was in the 1970s, but the days of popping in to pitch ideas to the Controller of Radio 4 and the Head of Light Entertainment are long gone.

BBC executives are now imprisoned by bureaucracy and protocols. It’s not just the money that’s luring the talent away from the Beeb to commercial radio and podcasting.

In 1970, I was doing freelance journalism, too. According to the diary, ‘£15 for the Spectator piece. Punch: £26 5s 0d. Vogue: £25. Guardian: £18. It adds up. I had lunch with Lynn Barber from Penthouse A disappointing experience, given the nature of the magazine: she was completely unsexy and made sex seem completely unsexy. But she has £20 to offer me for an article – so I’m going to give it a go.’

And I’m still giving it a go. (Lynn Barber is, too.)

A new year beckons. If you haven’t before, 1st January is the day to start. Yes, keep a diary and someday it could keep you.

Gyles Brandreth’s Diary

The Oldie December 2022 9

The Queen visits Manchester, 1968

I think it’s all over. It will be soon

After 50 years of dreaming, I know we won’t win the World Cup matthew norman

This question may look deceptively rhetorical, but it begs a starkly literal answer.

Is laughter the best medicine?

No, it is not. If it were, those diagnosed with atrial fibrillation would be prescribed a Seinfeld box set instead of a blood-thinner and beta-blockers.

But imagine for a moment that laughter is a uniquely effective drug. In that event, anyone exposed to John Cleese these past several decades has been in the placebo group.

Mr Cleese’s bitter resentments and ravening sense of entitlement denied have transformed him from arguably the funniest man on the planet to the least amusing life form in this, or any, quadrant of the galaxy.

Yet we cannot damn an aperçu out of contempt for its mouthpiece. So the time comes, as every fourth year, to trot out the Michael Frayn line Mr Cleese’s character speaks in Clockwise:

‘It’s not the despair. I can take the despair. It’s the hope [I can’t stand].’

Writing a few weeks before the World Cup begins in the traditional footballing stronghold of Qatar, the hope for anyone shackled by birth to the compulsion to support England remains minimal.

This is as it should be. Both painful history and dismal recent form preclude optimism.

Yet, once the tournament starts, the primal instinct to hope will trump experience. One adequate performance will strip away the top layer of realism like sulphuric acid on paint.

It is always thus. The team could comprise 11 men randomly chosen from the electoral roll, two amputees among them and not all of them sighted, and a flukey 1-0 win over the plucky little octogenarians from Vatican City would ignite the expectation that Harry Kane will lift the Jules Rimet trophy.

Football is the most wickedly

distorting game known to mankind. It obliterates not only common sense, but moral sensibilities.

Obviously, it will be wrong even to watch the tournament on television, thereby giving tacit approval to an odious regime. Anyone with any respect for human rights should boycott this World Cup.

But there isn’t a football fan alive whose convictions will survive a collision with the desperation for a World Cup victory.

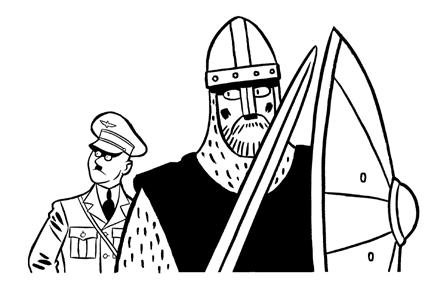

If a reincarnated German Chancellor somehow qualified to represent England, and came on as a late sub to win the trophy with a last-minute pile-driver from 25 yards, the chant of ‘One Adolf Hitler, there’s only one Adolf Hitler’ would echo through every city, town, suburb and village. And yes, Hampstead, that includes you.

Speaking of the Führer brings us seamlessly to the cause of the unbroken football failure on foreign soil that has plagued us since 1950.

Never outside the homeland has England won a tournament knockout match against a major footballing power (Brazil, Argentina, France, Germany, Spain, Italy or the Netherlands). Not once.

This record defies the law of averages too completely to be coincidence. It bespeaks the crushing inferiority complex, however flimsily disguised in sequinned robes of conceit, sired by the aftermath of the Second World War.

Winning the war but losing the peace explains almost everything, Brexit included, that has transformed this nation into a global joke far droller, in its

macabre way, than anything Mr Cleese has conjured in 40 years.

So it is that in football, as elsewhere, the English veer between the arrogance born of standing alone against the Hun and the defeatism born of still having to ration bread in 1954, when the German and Japanese economic miracles were in full swing.

The specific frailty was seeded in 1970, when Alf Ramsey’s defending champs contrived to lose a quarter-final to West Germany despite leading 2-0 with barely 20 minutes left.

That was the first game I ever watched. I was six years old. At full time, when the score was 2-2, my parents sent me to bed. This loving bid to spare me the horror to come was futile. I heard the commentary through the wall, and sobbed myself to sleep.

That trauma inculcated the paralysing fearfulness that has seen England lose more major tournament games from in front (the last World Cup semifinal, for example, when Croatia won from behind) than most of their rivals combined.

Prepare to enjoy the latest instalment of this sporting mystery play in a few weeks, more than likely in a quarter-final against the first serious opponents we encounter.

A couple of days later, reports will appear about a precipitous rise in the number of heart attacks recorded immediately after the defeat.

For victims with the outlandish good luck to be collected by an ambulance in time, the advice is mixed.

Those who want to live should know that, while laughter is not the best medicine, it has been shown to boost the immune system and speed recovery. Such patients should watch Fawlty Towers round the clock in intensive care.

Those for whom yet more World Cup heartache proves the final straw, and who deem it the ideal moment to check out, will find John Cleese on GB News.

Grumpy Oldie Man

10 The Oldie October 2022

Outside the homeland, England has never won a match against a major footballing power

TWO subscriptions for only £65, saving £53.80, and get one FREE copy of The Oldie Annual 2023 AND one FREE copy of The Very Best of The Oldie Cartoons worth a total of £15.90

THREE subscriptions for just £79 – BEST DEAL, saving £99.20, AND get the two books plus The Oldie Travel Omnibus, worth a total of £21.85

your

Oldie offers,

NAME OF DONOR ADDRESS POSTCODE EMAIL PHONE: RECIPIENT NAME 1 ADDRESS POSTCODE EMAIL PHONE RECIPIENT NAME 2 ADDRESS POSTCODE EMAIL PHONE RECIPIENT NAME 3 ADDRESS POSTCODE EMAIL PHONE DETAILS I would like to give a subscription(s) Please send the free books to me, the donor. (We will also send you a gift card to personalise and pass on.) Please choose a start issue: January (on-sale 14th Dec - reply by 28th Nov to guarantee delivery of this issue) February (on sale 11th January - reply by 16th Dec) PAYMENT DETAILS - choose one of two ways to pay 1. BY CHEQUE: I ENCLOSE MY CHEQUE FOR £________ PAYABLE TO OLDIE PUBLICATIONS LTD OR 2. BY CREDIT OR DEBIT CARD: PLEASE CHARGE MY VISA MASTERCARD WITH £ CARD NO: START DATE EXPIRY DATE MAESTRO ISSUE NO SIGNATURE SP122022 MAESTRO DATE

solved by The Oldie Give 12-issue subscriptions from just over £2 an issue SAVE OVER £99 AND GET THREE FREE BOOKS The Oldie December 2022

The Oldie Month 2016 11The Oldie October The Oldie is published 13 times a year, which means a 12-issue subscription runs for 48 weeks. The Oldie collects

data so that we can fulfil your subscription. We may also, from time to time, send you details of

events and competitions, but you always have a choice and can opt out by emailing us at help@subscribe.theoldie.co.uk. We do not share your data with, or sell your data to, third parties. Details you share with us will be managed as described in our Privacy Policy here: https://www.theoldie.co.uk/about-us/privacy

Christmas

GIVE ONE 12-issue subscription for £39, saving £20.40 on the shop price, and get one FREE copy of The Oldie Annual 2023 worth £6.95

OR Complete the form below and return it with your payment to: Freepost RTYE-KHAG-YHSC Oldie Publications Ltd, Rockwood House, 9-16 Perrymount Road, Haywards Heath, RH16 3DH OR CALL 0330 333 0195 NOW ORDER NOW AT www.oldiegiftsubs.co.uk using offer code

FOR OVERSEAS SUBSCRIPTIONS, simply add £5 per subscription to the above rates. Example: one UK sub, one Europe sub and one Australian sub will cost you just £89. This offer is applicable only to recipients who have not subscribed for six months or more.

SP122022

The British Visitor’s Passport (BVP) was a simplified version of the standard passport and was introduced in March 1961. It could be used by any British citizen, British Dependent Territories citizen or British Overseas citizen who had been resident in the UK for more than eight years.

It could be obtained from any post office, as long as the applicant could provide a passport photograph and a birth certificate or valid ID. It could be used for holidays or private visits of no more than three months’ duration to specified European countries – and Bermuda!

The visitor’s passport was valid only for a year. However, if you booked a last-minute break and then discovered that your BVP had expired, there was no need to panic. You had only to pop to your local post office and obtain another on the spot. No messing around with check-and-send or tracking numbers.

Instead, you left the post office with a new visitor’s passport in your pocket.

Another advantage was that you could get a family BVP, which could include your spouse and any children under 16. Photographs of husband and wife were glued to the inside fold, along with their address, dates and places of birth, heights and distinguishing features. Children were listed underneath.

This approach to travel documentation might seem rather cavalier now, but it was the days before large-scale international terrorism, people-smuggling, quarantines and all the other problems with which travel is now beset.

Everything seemed much more straightforward. There was no struggling with automated passport controls and face-scanners. Instead, you took your family across an international border with one light, flimsy, cream-coloured card, folded in three.

At the beginning of the 1960s, the advent of the British Visitor’s Passport heralded a bright future where we could all spend our summers under canvas in the Pyrenees and our winters on the Costa Brava.

Travelling to visit our European neighbours took off. Remember the birth of package holidays? School exchanges? Not to mention booze cruises to France!

How different it all feels today when, even for the most intrepid traveller, crossing international boundaries has become more complicated than ever. The BVP seems like a magical token from a time of insouciance.

Owing to concerns about its easy availability and the inherent security implications, the BVP was withdrawn on 1st January 1996.

But the cardboard documents still have curiosity value. In 2015, a cancelled British Visitor’s Passport, belonging to the artist Damien Hirst, was sold at auction for £875.

Liz Treacher

Generative artificial intelligence is the next wave of the digital revolution, if we are to believe the soothsayers of Silicon Valley.

Most of us are familiar with commonor-garden artificial intelligence – when machines figure stuff out for themselves, usually by processing enormous amounts of data at a speed no human can match. One practical application is Facebook’s surveillance software combing through your personal information to try to sell you the oven gloves you bought last week.

The thing about this form of AI is that it’s basically a glorified calculator. It can’t make the creative leaps that are a feature of human intelligence.

That’s why generative AI is exciting. It can process all our lovely data and remix it into pictures, songs, poems, novels, programmes, articles and videos that appear to be brand-new.

Take OpenAI’s Dall-E program. You type in whatever you want into a text box and the computer will come up with four convincing pictures of it for you. Say, ‘Manhattan skyline as painted by J M W Turner’. Or ‘A boat that looks like Homer Simpson’. Or ‘Three hagfish devouring Donald J Trump.’

Actually, you can’t do that last one: Dall-E comes with a few in-built ‘guardrails’ – no sex, no violence, no celebrities – to prevent abuse. However, there are plenty of rivals that aren’t as worried about ethical niceties.

People are already using one of them, Stable Diffusion (whose parent company was recently valued at $100 million), to make AI porn. The era of explicit videos starring whomever you please isn’t far away.

In the meantime, those videos are

prone to eerie glitches and limbs sprouting in weird places. Dall-E is great at creating Muppet memes but isn’t so good at human faces. Its musical equivalent, Jukebox, can do a passable Abba pastiche – at least until the vocals come in.

But the quality is improving all the time. This summer, a digital artist named Jason Allen won first prize at the Colorado State Art Fair with an image he created using the programme Midjourney. It prompted a lively online debate about whether computers can, indeed, create art.

I recently put this question to a philosopher of aesthetics. His answer was ‘Yes. But only bad, derivative art.’ Which needn’t be a problem, the professor reasoned. Plenty of people are perfectly happy with bad, derivative art.

Richard Godwin

12 The Oldie December 2022

what is generative artificial intelligence?

what was a BritishVisitor’s Passport?

AI image made by asking for ‘Underwater teddy bears using ’90s tech’

I was Peter Cook’s caddy

The great comedian would have been 85 on 17th November. When he played golf with Madeline Smith, he captured her heart

On Monday 25th August 1980, most people were asleep when Betjeman’s Britain was aired at 10.40pm on ITV.

A selection of John Betjeman’s poems had been set to music by composer Jim Parker, and visually represented by various television heavyweights including Eric Morecambe, Peter Cook and Susannah York.

Peter Cook (1937-95) played the dedicated golfer in Betjeman’s poem Seaside Golf. I was his put-upon caddy, reluctantly trailing behind him on the course. Both of us were dressed to the nines in exquisite Edwardian costumes.

Our poem was brought to Technicolor life on the windswept Sheringham links course in Norfolk.

Australian director Charles Wallace had hawked his project around the TV stations for nearly two years. A half-hour programme of poems had little appeal to the networks.

The idea was heavily influenced by the recent release of an LP, Banana Blush: Betjeman poems, read by the poet himself, set to gentle brass-bandinspired music by composer Jim Parker.

Jim lived in Barnes, a leafy London suburb, but was originally from Hartlepool, and a long-time resident member of the Barrow Poets. This jolly group of musicians and narrators would set up shop and perform in pubs, basements, crypts and any number of small-scale venues all over the land.

Charles Wallace was smitten.

After a slow couple of years, Anglia Television finally bit.

Philip Garner was the highly regarded controller of the station. He realised their arts output had been sorely neglected and decided that a

programme highlighting the works of the Poet Laureate might provide a temporary solution.

A commission appeared. Philip, a member of Sheringham Golf Club, could provide the location. The Links Hotel for Charles, the camera crew, Peter Cook and me was provided free of charge.

What a thrill to act opposite Peter Cook, a teen idol of mine. When I was just 15, in the mid-sixties, a friend whose father was something in PR kindly took me to the BBC Studios in White City. We saw a recording of Not Only… But Also…, one of the most popular light-entertainment shows at the time.

Peter Cook and Dudley Moore were the stars, but I had eyes only for Pete (who would have turned 85 on 17th November).

My idol did not disappoint when we came to make our film in 1980. Peter made me laugh so much – with ‘business’ that was not even in the script – that I actually felt quite ill with hysteria.

Peter could have carved out a successful career as a mime artist. To amuse me, he performed some ridiculous antics with the wing mirror of our ancient prop car, fiddling around with a cloth and copious amounts of spit and polish. Dear, silly Peter.

When I greeted him on our second day of filming, it was obvious that make-up could not hide his pallor. Peter looked ghastly.

He told me he had dreamt of murdering his friend Dudley Moore. He felt that Dud had deserted him with his

ambitions for stardom in America. Pete had himself tried to make it in the USA, but with patchy success. He returned, much chastened, to these shores.

So Peter had now just spent an unholy night wandering the corridors, mostly in conversation with the hotel’s commissionaire.

Then disaster fell. The pre-digital film in the second camera was out of focus and therefore did not match successfully with the film in the first camera.

We returned again to the golf course on a bleak autumn day to recapture the entire poem. Our faces DO look strained, but only I would notice!

Peter’s costume had not been retained – so none of the previous footage could be used. Once more, I was required to wear high-heeled shoes on the green – which, in normal circumstances, would have had us expelled from the club for life. Peter was apopleptic at the breach of custom.

Rightly so. In real life, he was a consummate golfer (in one inspired moment, he campaigned for Hampstead Golf Club to host the US Masters) and knew the etiquette. I walked on tiptoe – not easy on grass already sodden by east-coast October rainstorms.

My hero Peter asked me for my phone number. There being no mobiles in those days, I gave him the direct home line, with a warning that the call might be answered by a man.

Inevitably, I never heard from Peter, and within a matter of a few years he had become a bloated and tragic figure, dying in 1995, aged only 57. He would have been 85 this November.

I often think how different things might have been. For him. For me. Had I not told him truthfully that I had a partner.

The Oldie December 2022 13 LAWRENCE LEVY PHOTOGRAPHIC COLLECTION AND THE LEVY FOUNDATION

With Madeline, 1980

Get in the hole! Cook, 1983

A vintage road trip to Brighton

On 2nd November 1952, the main cast of a new Rank Organisation comedy joined the start of the London to Brighton Veteran Car Run.

The management at Pinewood was unenthusiastic about the film’s prospects. None of the four leads was well known.

Who would pay 1/9d to see a film about the owners of two elderly vehicles?

The inspiration for Genevieve was from the expatriate American writer William Rose, who witnessed the 1950 Brighton Veteran Car Run pass his Sussex cottage.

The South African-born director Henry Cornelius finally optioned the script, but his alma mater Ealing Studios turned down the production, claiming lack of space.

Eventually, Rank agreed to provide 70 per cent of the £115,000 budget, with the remainder from the National Film Finance Corporation.

Cornelius’s original choices of leads were Dirk Bogarde and Claire Bloom as Alan and Wendy McKim, but he eventually cast John Gregson and Dinah Sheridan. Bogarde advised her the part was ‘really you’, even if the director unchivalrously informed her that, at 31, she was too old for the role.

As for the McKims’ rivals, Cornelius had been highly impressed by Kenneth More’s stage performance as Freddie Page in The Deep Blue Sea. He told the actor that the part of Ambrose Claverhouse was written with him in mind. This was not entirely true: it was initially intended for Guy Middleton.

Finally, Kay Kendall, an actress in the tradition of Carole Lombard, was to be the bon viveur and trumpet-player Rosalind Peters.

The 57-day shooting schedule started in September 1952. The Veteran Car

Club of Great Britain suggested a Darracq 10/12 HP Type O and a Spyker 14/18 HP ‘Roi des Belges’ Open Tourer for the leading vehicles.

Gregson took the wheel for a few scenes, despite not having taken a driving test. Sheridan remembered ‘trying not to be seen giving him instructive help out of the side of my mouth’. The actor was so nervous that he hid a glass of milk on the floor so he could quell the symptoms of an ulcer.

A standard 1950s comedy would have extensively featured back projection, but ‘internal accountancy’ ruled out Genevieve’s using Pinewood’s sound stages. Instead, the cinematographer Christopher Challis described how the crew would ‘take advantage of whatever turned up’ on location.

Frequently, dire weather meant that the cast had to drink brandy so their faces wouldn’t look blue with cold.

Cornelius mortgaged his house to fund the completion money, but the production eventually ran out of budget. More remembered ‘little men prowling around the studio, switching off lights that weren’t needed’.

Meanwhile, pressure from the American distributors meant Larry Adler, the composer of the Genevieve Waltz (and later an Oldie columnist), would not be credited in US prints of the film until 1991.

When shooting finished in February 1953, Rank’s head of production, Earl St John, was unimpressed: ‘We may get a few car nuts to go along and see it.’

In fact, Genevieve became the UK’s second-most successful box-office attraction, and the British Film Academy declared it the Best British Film of the Year.

One reason for such acclaim was a cast that was, quite simply, perfect, from

14 The Oldie December 2022

When Genevieve was filmed 70 years ago, no one predicted it would be such a huge hit. By Andrew Roberts

‘A Ladybird Book vision of the Home Counties’: Genevieve

Sheridan’s witty and resigned wife to Gregson’s understated depiction of the keen motorist as a petulant, overgrown schoolboy.

Genevieve’s success also meant the elevation of Kendall and More to the stardom befitting two of British cinema’s finest light comedians.

The sequence of Rosalind miming to Kenny Baker’s trumpet belongs on a BFI list of Top Ten Sublime Screen Moments. Cornelius so liked the actress’s mistaken reference to playing the ‘plumpet’ that he kept it in the final cut. As for More, Claverhouse represented his long-term goal of a film role of ‘real character’.

As with any comedy of note, there was also an impeccable supporting cast: Joyce Grenfell’s hotelier, surrounded by aspidistras; Reginald Beckwith as a hapless Allard owner;

and a cameo from Leslie Mitchell, the voice of Movietone News.

Above all, there is Rose’s script with its affectionate but not uncritical eye for British eccentricities. Penelope Houston wrote in Sight and Sound that Genevieve had ‘a hard urban flavour’; the dialogue between the McKims is remarkably frank. Cornelius had to shoot two versions of their bedroom scene in case Rank decreed the first ‘a shade too French’.

Today, the Darracq and the Spyker are part of the Louwman Collection of vintage cars.

It is difficult to appreciate that the

Clockwise from top left: Kay Kendall, Dinah Sheridan, John Gregson, Kenneth More; Gregson and Sheridan on Genevieve; Sheridan is made up; Susie the dog and Sheridan. All taken in 1952

picture that made them world famous is 70 years old – until you recall that Michael Medwin, who played a young expectant father, died in 2020, aged 96.

Genevieve captures a Ladybird Book vision of the Home Counties, with the London described by Gavin Stamp: ‘shabby and ravaged, full of bomb sites and dereliction, and yet which is somehow authentic’. Much of the traffic looks pre-war, with the occasional Ford Consul as a harbinger of the affluent society.

It is a film that barely dates precisely because is so firmly rooted in time and place – and because, even today, certain old car enthusiasts are prone to ‘hawling like brooligans’.

The final words should go to Dinah Sheridan: ‘Genevieve will be our epitaph.’

The Oldie December 2022 15

TRINITY MIRROR / ALLSTAR / PA / EVERETT COLLECTION / ALAMY

Crumbs! Biscuit king turns 200

Mark Palmer salutes his

Silly, really, but whenever someone asked where I grew up, it was with some embarrassment that I’d reply, ‘Reading’.

I always harboured affection for the place, despite being aware of its shortcomings.

Much of the architecture was grim. Progress in the 1960s and ’70s was measured by how many shopping centres and one-way systems the town planners could get away with.

But I was invited back there recently to celebrate ‘Reading – Biscuit Town’ in the company of the Mayor, the ViceChancellor of Reading University and other local dignitaries.

We were marking the 200th anniversary of Huntley & Palmers. The Palmers arrived on the scene in 1841, and in 1822 Joseph Huntley opened his first baker’s shop at 72 London Street, Reading.

There are bicentenary lectures about the company’s former 25-acre site opposite Reading Gaol. You can take a Huntley & Palmers audio trail ‘through the world of biscuits’. Do visit the 300-odd biscuit-tin collection in the town hall – or pay a fiver to join one of Terry Dixon’s ‘Biscuit Crumb’ walks.

founded Huntley & Palmers

Terry’s mother worked in the factory in the 1950s and ’60s, first as a ‘picker’ – removing any damaged or substandard biscuits from the conveyor belt – and then in the firm’s Recreation Club.

‘I’m Berkshire born, Berkshire bred; strong in the arm, thick in the head,’ he says when we meet outside what’s left of the original 1860 railway station, from where you could smell the ginger nuts being roasted in the factory 400 yards or so away.

The factory has long gone. Once Associated Biscuits (Huntley & Palmers, Jacob’s, Peek Freans) was gobbled up in 1982 by Nabisco, the magnificent, late art-deco headquarters of what was once the most famous biscuit company in the world was replaced by a hideous Prudential Insurance building in a savage act of legal vandalism.

‘But the legacy of Huntley & Palmers lives on and its influence on the town cannot be overstated,’ says not-in-theslightest-bit-thick-in-the-head Terry, producing from his rucksack a small H&P tin made for the Queen’s Coronation, with a dozen or so Iced Gems inside. ‘Biscuits put Reading on the map.’

This is not strictly true. It was on the

map in 1121 when Henry I founded Reading Abbey, thought to be bigger than either Winchester Cathedral or Westminster Abbey. The abbey was closed by Henry VIII in 1539 and then almost razed to the ground during the Civil War on the orders of Charles I, who feared it would become a parliamentary stronghold.

Still, by the beginning of the First World War the Huntley & Palmers factory employed more than 6,000 people – over a quarter of the working population of the entire town – and was exporting to 134 countries. It held the Royal Warrant of every royal household in the world.

It was the ‘first name you thought of in biscuits, second to none in cakes’ – at least, that was what the advertising slogan said. ‘Huntley & Palmers make ’em like biscuits ought to be’ was the jaunty television commercial I remember the best.

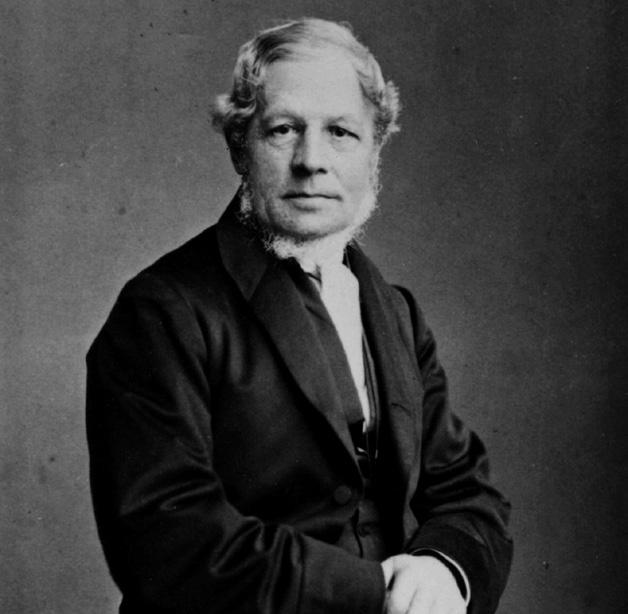

My father, the last chairman, spent all his working life at Huntley & Palmers –as did my grandfather, great-grandfather and great-great-grandfather. It was my great-great-uncle, George Palmer, who forged the alliance with his Quaker cousin, Thomas Huntley, in 1841.

Joseph Huntley (1775-1857); George Palmer (1818-97); George V at Huntley & Palmers, 1918 – the factory also made munitions

Joseph Huntley (1775-1857); George Palmer (1818-97); George V at Huntley & Palmers, 1918 – the factory also made munitions

16 The Oldie December 2022

ancestors, who

Huntley took care of the baking, while Palmer developed the first continuously running machine for biscuit-manufacturing.

In some countries, tins of H&P biscuits achieved an exalted status. In 1890, two were discovered being used as ornaments on an altar in a Catholic church in Ceylon. A Mongolian chieftainess was said to have grown garlic heads in one as an ‘upward and visible sign of her high position’. In Uganda, Bibles were kept safe from destructive white ants in biscuit tins. In 1904, when Sir Francis Younghusband became the first European to visit the holy city of Lhasa, in the Forbidden Kingdom of Tibet, he was welcomed by a stack of biscuit tins to assure him the locals were in touch with civilisation.

The biccies may have been good, but they weren’t works of art – unlike the tins, which were fashioned into handbags, binocular cases, suitcases, rows of books, buses and post boxes.

Henry Stanley took some with him on his trek across Africa in search of Dr Livingstone and made peace with a potentially violent tribe in Tanzania by offering them a few smart-looking tins.

Captain Scott took Huntley & Palmers biscuits to the South Pole; a packet was found alongside his frozen body. One of those, wrapped in greaseproof paper, fetched £4,000 at a Christie’s auction in 1999.

In the late 1960s, I used to take friends from school on tours given by a formidable woman called Mary Cottrell. The highlight was when we were shown into a special room where we produced our penknives and hacked away at the massive blocks of chocolate. And I always backed Reading Football Club – the Biscuit Men.

Reading Gaol, designed by George Gilbert Scott, stands between the former site of the factory and the ruins of the abbey. It ceased being a prison in 2014 and is rumoured to cost £250,000 a year to maintain while the Ministry of Justice and Reading Borough Council argue over what should be done with it.

Many people think it should be turned into an arts centre, with a theatre, hotel, restaurants and bars – but the dreaded ‘luxury apartments’ solution inevitably will win the day.

Oscar Wilde visited the factory in September 1892, three years before he took up residency in the prison for two years. Terry thinks the Palmers may have had some influence on how he was treated during his confinement, but there is no evidence of this.

Top: On the Upper Congo River –Huntley & Palmers biscuits by the funnel, 1890

Below: Reading factory, opened in 1846. By 1900, it was the biggest biscuit-maker in the world

Above: Edwardian biscuit tin.

Below: Opera Wafers, 1890

Terry is worried that the younger generation in Reading have little idea about the Huntley & Palmers biscuit legacy. Perhaps, rightly, they are more concerned about the influence of the newly opened Elizabeth Line and how it might affect house prices.

But I doubt there will ever be a bigger benefactor to Reading than Great-GreatUncle George and his family. Much of the site of Reading University was donated by the Palmers, as was 49-acre Palmer Park, handed over to the Mayor of Reading on 4th November 1891.

George was Liberal MP for Reading from 1878 to ’85, but turned down the offer of a baronetcy from the Conservative Prime Minister Lord Salisbury because he regarded it as ostentatious. He was given the freedom of Reading, and a statue of him was unveiled on Broad Street. Designed by George Simmonds, it depicts him holding a top hat and umbrella – the only statue in Britain showing a man holding an unfolded brolly.

The statue has gone now. But I’m thinking of starting a campaign to bring the statue back to Broad Street. That would help keep the biscuit flame burning in a town of which I should never have been embarrassed.

The Oldie December 2022 17

Poetry and emotion

The album was beautiful, made of red leather with gilt-edged pages. My late mother, Linda Kelly, who was a historian and lover of the 18th century, with biographies of Sheridan, Tom Moore and Talleyrand to her name, had been given it by her mother-in-law shortly after she got married in the early 1960s.

She decided it was too precious to fill with anything so prosaic as recipes or addresses. She chose instead to keep it as a commonplace book – filled largely with poetry, and with bits of prose too – and she kept it on and off until the day she died nearly four years ago.

Poetry had always been an enthusiasm of hers, which meant it became an enthusiasm of mine, and is something I’ve been writing about for some time now.

In 2014, I wrote a memoir called Black Rainbow: How Words Healed Me – My Journey Through Depression. The book is about how poetry consoled me at the height of my battle with the illness.

Ever since, I’ve been running Healing Words poetry workshops for mentalhealth charities and in prisons.

But my mother’s death changed my attitude to poetry, and has led to a new book. It’s about how poetry can help your emotional wellbeing, which is why I’ve called it You’ll Never Walk Alone: Poems for Life’s Ups and Downs.

I was previously drawn to poems for difficult times. But my mother’s passing, counter-intuitively, has prompted me to explore poems about hope and joy, as much as about sadness.

If I’ve learnt anything from losing her, it’s that life is too short not to focus on the happy times.

So my book still includes poems such as Love (III), in which George Herbert brilliantly describes feeling ‘guilty of dust and sin’. But it also has others such as A Blessing by James Wright, in which the poet captures the

joyful moment he meets some wild Indian ponies in Minnesota: ‘Suddenly I realise / That if I stepped out of my body, I would break / Into blossom.’

Through this chance meeting, Wright finds a way to escape his materiality and loneliness.

The matter-of-fact language – notice how the poet imagines ‘stepping’ out of his body – makes the transcendence sound as simple as putting one foot in front of the other.

Both these poems, in different ways, help the reader feel, in the words of F Scott Fitzgerald, that our longings are ‘universal longings’, and that we’re ‘not lonely or isolated from anyone’.

Today, I’m drawn to different poems. My tastes have changed also when it comes to learning poetry by heart.

I now want to be more like my mum, someone who knew hundreds of poems from memory and could summon them at will, no smartphone required. As for many of her generation, it was commonplace at her school to learn a poem a week. She told me that she was also asked to learn poetry as a punishment for any minor transgressions.

One of my last memories of my mother is of her in the hospital dialysis unit – a windowless, airless room –attached to a machine she didn’t want to be attached to, with me desperate to distract her and make light of how miserable things were.

I looked up Tennyson’s The Lady of Shalott on my phone. It was one of the first poems I had ever learned by heart, something we had done together, I lying on the beaten-up olive-green sofa in our sitting room, she pacing the room correcting my mistakes.

Of course, she instantly realised I was

reading an inaccurate version online, not the Oxford Book of English Verse one. In that moment, I resolved to learn more poems by heart.

Once upon a time, this was not such an unusual pastime. Richard Ingrams, The Oldie’s founding father, recalls his schooling at Shrewsbury, where an English master, a man called McEachran, didn’t teach according to the curriculum.

‘He taught poetry in what he called “spells” – four- or five-line extracts which you had to learn by heart and recite,’ Ingrams recalls. ‘It was completely unlike anything else that was being taught at school and it made us interested in books and reading poetry.’

We children of the seventies and eighties were different. I don’t remember having to learn a single poem at St Paul’s Girls’ School.

And, more recently, I can’t recall any of my own children learning a poem by heart, unless it was encouraged with a bribe by me for some present or other. We have lost something.

I have found it invaluable to learn the kinds of emotionally companionable poems you will find in my book, in which I also share how best you might try to learn them. Now that I know at least some of my selections by heart, I engage even more closely with the feelings they evoke.

My mother knew all this only too well. Thanks to her, I now know it too. I like to think she is looking down from heaven, knowing her red leather album wasn’t in vain.

Rachel Kelly’s You’ll Never Walk Alone: Poems for Life’s Ups and Downs (Yellow Kite) is out now

When her mother died, Rachel Kelly found consolation in joyful poems – and learning them by heart

18 The Oldie December 2022 NEIL SPENCE

Emote by rote: Rachel Kelly

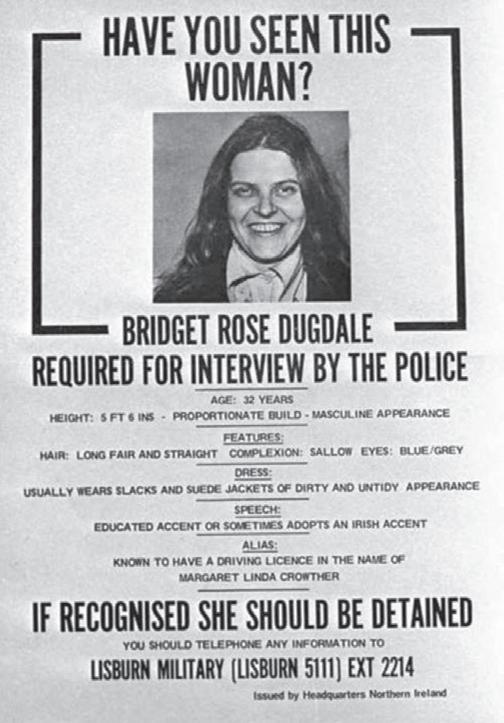

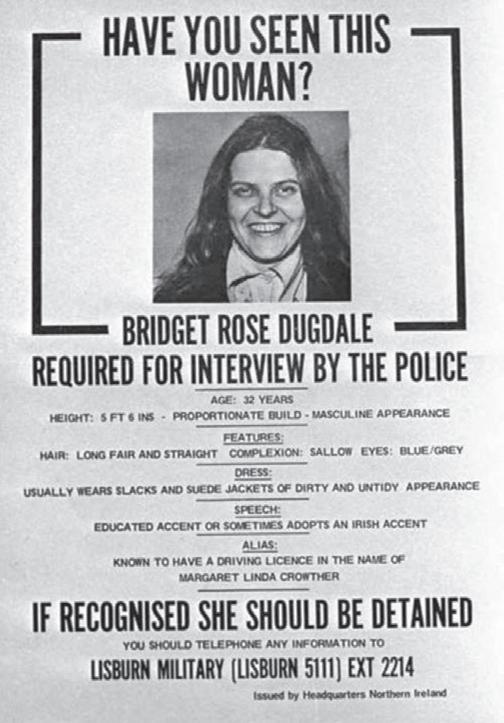

Virginia Ironside recalls Rose Dugdale – the deb who beat up her parents’ friends, stole Old Masters and built missile-launchers

School days with an IRA terrorist

When someone is in a class above you or below you at school, they might as well not exist. The age gap appears much greater during your childhood.

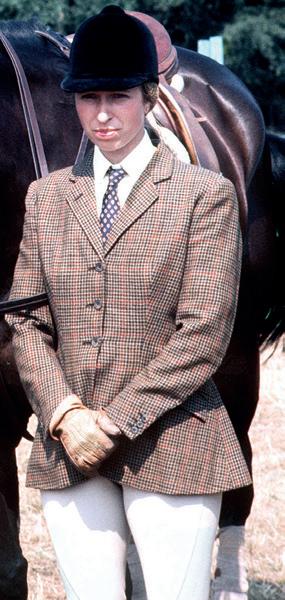

Rose Dugdale (born in 1941), the notorious IRA terrorist, was two classes above me at Miss Ironside’s day school – my two spinster great-aunts’ dame school in Kensington. Even though she was three years older than me, she made a great impression not only on me but on every girl in the school.

She was a bit gawky and masculinelooking – a big girl with a deep voice –and not conventionally pretty, but she exuded such energy, positivity, intelligence, generosity and, yes, even kindness that she was instantly attractive.

The last thing I would have imagined, at school, was her dropping bombs, constructing missile-launchers, trying to kill people and tying up her parents’ innocent friends to steal their valuable Old Master paintings.

But I sometimes wonder if the ethos of our old school had any part to play in her Marxist tendencies.

Rose had been brought up with stultifying conventionality. The two girls in the family – Caroline, her older sister, and Rose – were obliged by their mother to wear only blue frocks with matching ribbons in their hair – the best colour, apparently, for girls. They had to change into formal clothes for dinner and wear long white gloves. They had to curtsey to every visitor to their homes: one consisted of two town houses knocked together in Chelsea; the other was a vast estate in Devon, where Rose learned to ride and practise the piano.

Every hour of every day was

regimented by her parents – her mother was the ex-wife of John Mosley, Oswald’s brother. Rose agreed to ‘come out’ as a debutante – the last time this archaic ritual of young girls being presented to the Queen took place – only on condition that her father would allow her to try for Oxford.

In contrast to this bizarre and outdated home life, my great-aunt’s school was based on exceptionally liberal lines, inspired by Friedrich Froebel, the 19th-century German educational pioneer.

All the teachers – a bizarre, brokendown lot, sprinkled with eccentric geniuses – were called by only their Christian names. Rene, my great aunt, was known only as Rene.

Most were spinsters or lesbians. They were oddballs with no formal training –not a requirement at that time.

A teacher who loved Rose, because of her musical talent, was Stella Kelvin, an Austrian refugee working illegally who could fly into tremendous rages. She’d been taught by Theodor Leschetizky, who’d been taught by Carl Czerny, who’d been taught by Beethoven.

There was no staffroom. Loos – there were only two for 140 pupils – were for teachers and pupils alike.

There were no RE lessons. Although we sang a daily hymn at so-called ‘Prayers’ every morning (Rene played the piano), God or Christ was otherwise rarely mentioned.

Bullying was highly disapproved of,

20 The Oldie December 2022

KEYSTONE PRESS / PA/ ALAMY

and punishment was non-existent. The idea was for the school to be entirely egalitarian. However, if anyone was caught, say, whispering in class, we risked being ‘sent to Rene’, which involved waiting outside her sitting room before being called in to face her.

‘And why have you been sent to me?’ Rene would ask, in her faintly Scottish accent. When you tremblingly explained, she would fix you with a beady eye and simply say, ‘Well, I hope you never have to be sent to me again!’ And that was that.

Very few people wanted to be sent to Rene more than once.

Like a lot of the girls, I had a secret crush on Rose who, I suspect, had always been bisexual. Every girl wanted

to sit next to Rose at lunchtimes – ‘Oh, Rose, sit here!’ the cry went up.

After leaving school, Rose did indeed ‘come out’ and was presented to the Queen. Afterwards, she even spent a year going to dances and cocktail parties with a view to finding a husband.

Rose hated every minute.

At one ‘debs’ dance’, as they were known, Rose danced with a young ‘debs’ delight’, our editor’s father, the writer Ferdinand Mount.

After the dance, and making polite conversation on the balcony, Ferdy remarked something smarmy about the night and the party; he was rebuffed with a merry chuckle from Rose. She added, ‘It’s a complete and utter waste of money!’

When Rose finally got to Oxford, she had a passionate affair with Iris Murdoch and a tutor called Peter Ady (a woman). She made university history by posing as a man to get into the male-only Oxford Union debating society, which resulted not long after in women being officially allowed in for the first time.

After writing my first book, Chelsea Bird, in 1966, I spent the advance on going to New York. One of my contacts there was James, Rose’s brother, who had attended the kindergarten at Miss Ironside’s.

The only day we could meet was when he had a date with his sister – but that didn’t matter. Rose arrived, energetic and breathless, in an open-top red sports car and drove at great speed to Greenwich Village to take us to see a Greek tragedy.

Afterwards, she drove me back to my hotel – and I was impressed by her spontaneity, generosity and sheer fun. She seemed golden and blessed.

She was, however, becoming increasingly enamoured with the IRA cause. When she returned to England from the States, she became involved with Eddie Gallagher, an IRA sympathiser. Together, they decided to steal those Old Masters from friends of Rose’s parents, Sir Alfred and Lady Beit.

The Beits were immensely rich –Sir Alfred inherited diamond mines in South Africa and owned a huge art collection. They lived at Russborough House, County Wicklow, a wonderful Palladian pile, reputedly the longest house in Ireland.

In 1974, Rose, now a fully fledged IRA sympathiser, went with her partner (and later husband), Gallagher, to Russborough House.

They attacked the poor Beits in the middle of the night, pistol-whipping Alfred and tying him up. They ‘gave him a clattering’, according to Rose.

Among the pictures they stole were Gainsborough’s Madame Baccelli and Vermeer’s Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid. They plotted to keep the pictures in exchange for the release of three IRA prisoners.

Like most of their schemes, it didn’t go to plan. In 1974, she took part in a helicopter bombing raid on Strabane Barracks, County Tyrone. Rose was caught and sentenced to nine years in prison.

During her imprisonment, Rose gave birth to Ruairi, her son by Gallagher, also jailed (for kidnapping a Dutch industrialist). Martin McGuinness was one of Ruairi’s godparents.

On leaving prison, she became a weapons expert with her new partner, Jim Monaghan. Together they developed a shoulder-fired missile-launcher, dubbed the ‘biscuit-launcher’ because it used two packets of digestive biscuits to absorb the recoil.

Now aged 81, she lives in a nursing home, the Poor Servants of the Mother of God, in Chapelizod, a Dublin suburb.

So Rose became a monster. And yet, throughout her life, many people fell for her charms. Even now, I can’t think of her without smiling, despite knowing that I should be viewing her with horror.

I often wonder what Rene would have said.

Heiress, Rebel, Vigilante, Bomber: The Extraordinary Life of Rose Dugdale is by Sean O’Driscoll (Penguin £18.99)

The Oldie December 2022 21

Rose Dugdale, front row, fifth from left. Her brother James, second row, third from right, as Henry VIII. Virginia Ironside far left as a Velasquez princess. 1953

Left: dressed as a man (left) for the men-only Oxford Union, 1961. Above: wanted after Strabane bombing, 1974

GEORGE HURRELL

GEORGE HURRELL

The Great British Teeth Problem

More than 70 per cent of people aged 65 and upwards have some form of gum disease. Some of you will feel smug when you have finished reading this. Others will feel guilty and frightened.

But don’t worry – it is never too late to have gum disease halted by a dental hygienist. If you obey his or her orders, you may even have saved your life.

The role of dental hygiene in our health is underrated. Who knew that your risk of heart disease, diabetes and even Alzheimer’s can be considerably increased if you have inflamed gums?

Lesley, a leading Harley Street hygienist, says, ‘Anything that causes inflammation stresses your body out –just as smoking hardens your arteries – and stress makes you more vulnerable to opportunist illnesses.’

So how do your gums become inflamed in the first place?

It starts with bacterial plaque, says Lesley. ‘There are two sorts of gingivitis which make your gums go from being flat and a lovely pink colour to fat and red, and they are both caused by the evil bacteria in your mouth that build up during the day and sit around your gums –because they’re not being dislodged by you!

‘If you remove bacteria with flossing and brushing, ideally twice a day, it will keep things at bay. Tongue-cleaning is also a good idea, to keep bacteria down.’

But if you don’t dislodge the bacteria – aka plaque – that accumulate in your mouth every day, which start off as soft and easy to dislodge, they will go hard. And some of the plaque will set up shop under your gums – so you will be unable to remove it yourself.

She continues, ‘Basically, from the time that you get your adult teeth in your teens, you should be flossing between the gaps – because if you don’t, the gaps will get bigger.’

These gaps become repositories for food and bacteria, which will stagnate there, and the gingivitis will proceed to

periodontitis. The inflammation caused will eventually pull the gum away from the tooth. When this happens, the plaque and their toxins destroy the fibres that surround the tooth before going on to destroy the bone that holds the tooth in place. And that is why people’s teeth become loose.

Everyone is different, Lesley says. Some people have a lot of plaque around and it goes hard very quickly.

It was a dentist who frightened me into a rigorous routine when I developed ‘pregnancy gingivitis’ and was told my gums had started to suffer. Although my teeth themselves were fine, they would all fall out if I had no gums to secure them in place. There is an analogy with an egg and an egg cup holding the egg in place. The gums are the egg cup.

‘Destructive gum disease is very slow,’ says Lesley. ‘But you will be getting signs if your gums start bleeding as you’re cleaning your teeth and also when you look at your gums and you see they are red and inflamed instead of pink. This is your brain telling you “You have an alien invader.” ’

Don’t think you are being good if you just brush your teeth very well. Sometimes that’s not enough. You must brush the margin where the teeth and gums meet. This is where plaque likes to live.

Unfortunately, Lesley recommends using an electric toothbrush – one of

the most non-biodegradable products on earth.

Now how does gum disease affect our beauty potential? Lesley says, ‘Your breath may smell because you’ve got this blood residue hanging around. You probably won’t laugh or smile as much because you will be self-conscious. If your teeth are loose, you can’t eat properly – so your enjoyment in life has pretty much gone.

‘Your teeth may change position, and if you start losing teeth your face will change shape, and not in a perfect Joan-Crawford-cheekbones way –more like Ena Sharples from Coronation Street!

‘You can’t always just have implants, because sometimes the bone has disintegrated so much that there is nothing for the implant to hang on to. You don’t sleep well because breathing is hampered and so you look exhausted.’

Lesley gives a final warning: ‘Everyone’s talking about the gut microbiome at the moment: basically you’ve got one big tube going through you from the mouth to the anus. So it’s no good taking all these probiotics if you don’t sort out the health of your mouth first.’

And how do you do that? Go to a hygienist, spend an hour in the chair having the appalling stuff dislodged by a professional, and then pull yourself together and start following a regime.

Mary Killen’s Fashion Tips

The Oldie December 2022 25

Want to look like Joan Crawford rather than Ena Sharples? Then clean your teeth

It isn’t enough to go to the dentist. You must visit a dental hygienist to keep inflamed gums – and heart disease – at bay

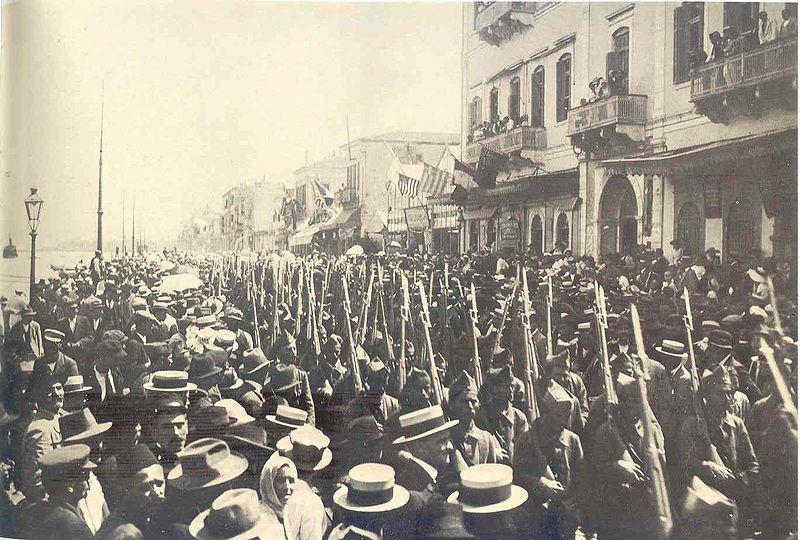

Smyrna, joy of Asia

‘D

on’t forget Smyrna!’ shouted Turkish President Recep Erdoğan in a speech this September.

He was referring to Smyrna, the main port on Turkey’s Aegean coast, and what happened to it 100 years ago.

From 13th to 16th September 1922, starting just four days after the flight of Greek forces and the entry of a Turkish army, a fire destroyed the city centre.

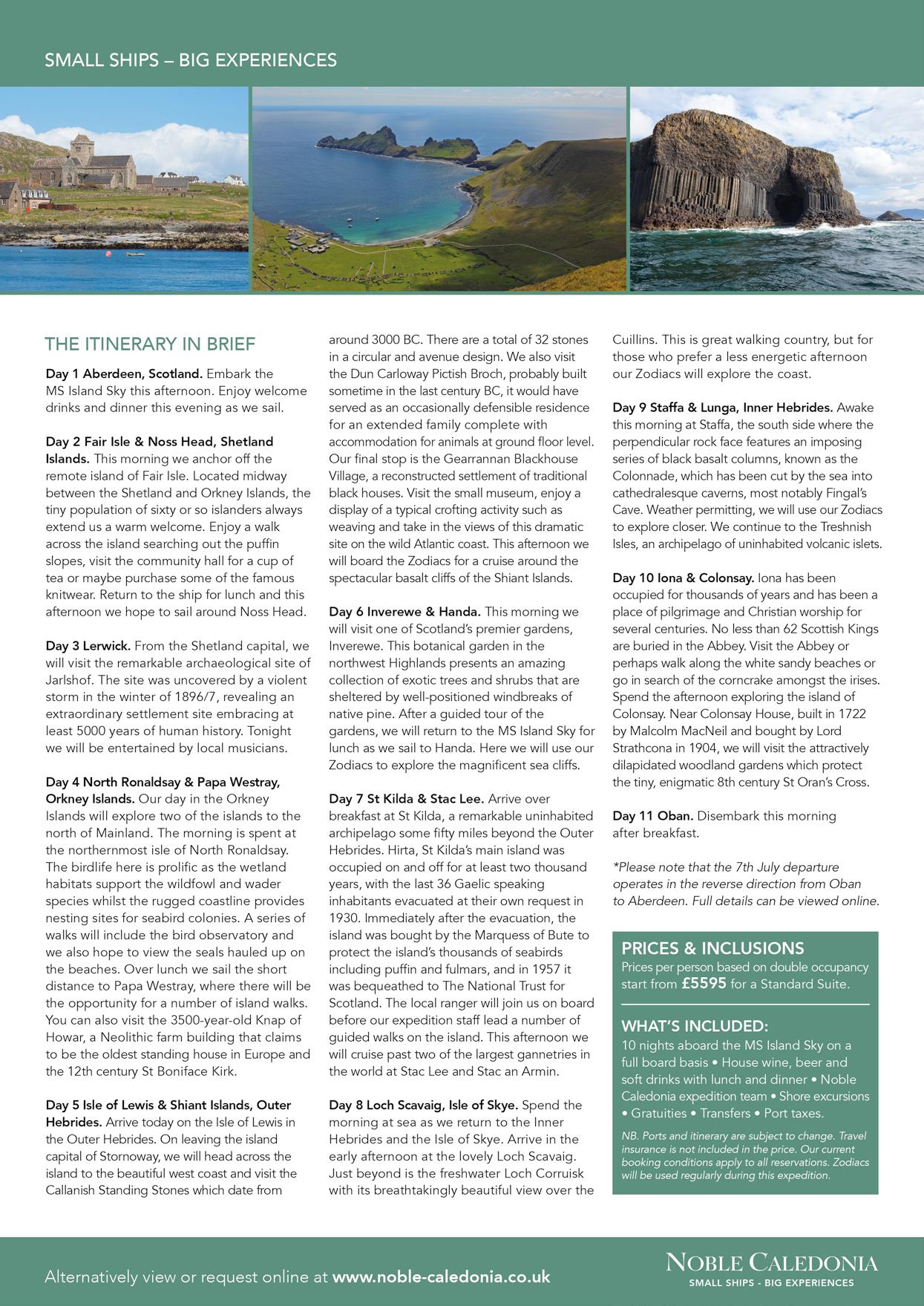

Greek and Armenian inhabitants fled to the waterfront, where they formed ‘a shrieking, terrified torrent of humanity’, according to George Ward Price, a British journalist watching from on board HMS Iron Duke (which eventually removed some of them). The fire, organised by Turkish soldiers, was followed by the murder or expulsion of 100,000 or more Greeks and Armenians.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Turkey’s founding father, denied Turkey’s responsibility, but he was the general in command of the city.

He told his future wife, Latife Hanim, an emancipated Turkish woman from Smyrna, as they watched the city burn, ‘Yes, let it burn! Let it crash down! We can replace everything.’

What Turks commemorate every year as the ‘liberation’ is remembered by Greeks as the ‘catastrophe’ – the elimination of all Greeks from Anatolia.

Britain has reason to remember Smyrna, too. For centuries, it had been a flourishing world city with a powerful British community – hence the presence of British battleships in the harbour in 1922.

Founded by Greek colonists in the seventh century BC, Smyrna was long a centre of Greek culture and was possibly Homer’s birthplace. It is situated at the end of a long, deep gulf where the Aegean projects into the westernmost point of Asia. A natural link between Europe and Asia, it was called by the Romans ‘the joy of Asia’.

After over 1,000 years in the Roman Empire, Smyrna was ruled by Turks, the Genoese, the Knights of Saint John and Venice. By 1480, it was a small market

town in the Ottoman Empire. Its Turkish name, İzmir, came from the Greek phrase ‘eis teen Smyrna’: into Smyrna.

Its location and its harbour soon attracted French, Dutch, English and Venetian merchants, as well as Turks, Greeks, Jews and Armenians.

In 1634, the French jewel merchant Jean Baptiste Tavernier could write, ‘Smyrna is today for trade by both sea and land the most famous city of all the Levant and the most famous market for every merchandise going from Europe to Asia and from Asia to Europe.’

It exported fruit – Smyrna figs are the best – carpets, opium and antiquities. The population rose from 5,000 to around 100,000, periodically reduced by plagues and earthquakes.

Mosques, churches and synagogues flourished side by side. Christians lived in ‘great freedom’ – despite occasional massacres. After Greek independence in the early-19th century, thousands of Greeks moved to Smyrna. They preferred prosperity in the Ottoman Empire to freedom and chaos at home. Turks called the city Gâvur İzmir – ‘Infidel İzmir’.

By the mid-19th century, the city contained more Greeks than Turks – 55,000 Greeks to 45,000 Turks (and 13,000 Jews and 5,000 Armenians). Some 12,000 western Europeans included several thousand English and Maltese.

Helped by the city’s English merchants, Smyrna started the Ottoman Empire’s first newspaper, first railway and first football club: Bournabat Football and Rugby Club, established in a Levantine suburb in 1894. The red-and-yellow Tulipa whittallii is named after a prominent British family of Smyrna. Praising its modern schools and businesses, the Austrian consul-general wrote, ‘Smyrna illuminates like a beacon all the other provinces of the Ottoman Empire.’

The two-mile-long stone quay, known as the Kordon, built by French engineers in 1869-76 (where so many Smyrniots would perish in 1922), was lined with cafés, hotels and warehouses. If Smyrna was ‘the eye of Asia’, it was said, the quay was ‘the pupil of the eye’.

The writer Norman Douglas called Smyrna ‘the most enjoyable place on earth’. One café, where you could ‘pick up a girl or anything else you fancied’, had bedrooms on the upper floors for ‘an hour’s rest’. He asked, ‘Why are such delectable places not commoner?’

The city’s brand of music, called Smyrnaika or rebetiko, mixed western polyphony and eastern monophony.

Songs described the torments of love, and the pleasures of hashish and alcohol: ‘You stay up all night at the cafés, chantant, drinking beer.’

26 The Oldie December 2022

The ancient city bustled with trade and naughty pleasures – until it was destroyed by arson a century ago. By Philip Mansel

Bournabat FC, Smyrna, 1890s

The bell tower of Smyrna’s former Greek Orthodox Cathedral, Agia Fotini

A Papazoglu, a musician in one of the cafés on the Kordon, said, ‘We played Jewish and Armenian and Arab music. We were citizens of the world, you see.’ Indeed ‘Gâvur İzmir’ was so cosmopolitan that, to many visitors from the Turkish hinterland, it seemed – as does London or New York today – like a foreign country. Envy and resentment, as well as the Greek occupation in 1919-22

Above left: the Greek Army march in Smyrna, May 1919. Left: the fire in September 1922 prompted a chaotic evacuation. Above right: after the fire. Below: 4th-century BC Agora of Smyrna, ruined in 178 AD by an earthquake

and Greek atrocities in Anatolia, contributed to the 1922 catastrophe.

Since 1922, however, İzmir has reverted to its natural role as a great Turkish and Mediterranean port. Only 40 per cent of the city was destroyed: the Greek and Armenian districts, not the Turkish, Jewish or Levantine ones.

New Turkish inhabitants were often immigrants from Greece and the

Balkans. The remaining Levantines helped restart the export trade.

In 1941-44, Major Noel Rees, the British Vice-Consul from a prominent Smyrna family (whose initial R can still be seen on the ironwork of their former office on the Kordon) and the local head of MI9, made Smyrna and its coast the heart of the escape lines for thousands fleeing German-occupied Greece.

Confirming the power of geography, İzmir and the coasts of Turkey are today bastions of the secular CHP (Republican People’s Party) against the increasingly dictatorial Islamist government in Ankara. There are seven universities.

Turkish friends say that it is the last big city in their country where they ‘feel freedom’. In alcohol consumption, and in the number of unmarried couples, the packed cafés on the Kordon resemble those in other Mediterranean ports more than those in inland Turkish cities.

For a city of four million, İzmir is exceptionally peaceful.

The city is reconnecting to its past. In 2009, it was twinned with Thessaloniki in Greece. Museums founded by the local shipping magnate and wine-producer Lucien Arkas commemorate the glories of Smyrna.

September 2022, like every September, was marked by a military parade – and also by a pop concert on the Kordon by the Turkish singer Tarkan. No one mentioned the fire and massacres of 1922.

Smyrna’s catastrophe in 1922 remains a warning to world cities today. The hinterland always bites back. Nationalism corrupts. Absolute nationalism corrupts absolutely.

Philip Mansel is author of Levant: Splendour and Catastrophe on the Mediterranean (2010), a history of Smyrna, Alexandria and Beirut

The Oldie December 2022 27

Upwardly mobile

Don’t mock the young for being glued to their phones. Caroline Flint, 81, depends on hers to stay in touch with the best things in life

Ihave friends the same age as me (81) and many much younger –here I include grandchildren. The greatest difference between them is my ability to contact them and communicate with them.

With friends of my own age, I am very restricted in my ability to contact them. I can write a letter – pen to paper, envelope, stamp, shuffle to the post box – and hope that it is picked up by the increasingly depleted Post Office.

On the other hand, I can ring them. Invariably this has to be on a landline because although they own a mobile, it is never switched on. ‘I put it on only when I want to call out.’

This means that the great convenience of the mobile phone – you can answer it by pulling it out of your

pocket; you don’t even have to get out of your chair – is not used.

People are fearful that if they have their phone switched on all the time, they will be called all the time. They should be so lucky! How many of your friends or relatives will be ringing you on a normal day? They are all busy living their lives – they aren’t interested in ringing you every five minutes.

So I ring the landline. It is never answered. I leave a message on the answerphone. Will this be picked up? I am not very confident, but if I am lucky it is answered – sometimes within a week.

I text my younger friends. They text back immediately.

We can have a conversation on text. ‘Did you get that job?’ ‘Where are you on holiday?’ ‘Are you in a hotel or Airbnb?’

Tell me about it.