The Mass Cultural phenomenon

‘CORE’ EXPLORED THROUGH GRUNGECORE

ACADEMIC ESSAY

Kurt Schwimmbacher

231002

27 MARCH 2024

Kurt Schwimmbacher

231002

27 MARCH 2024

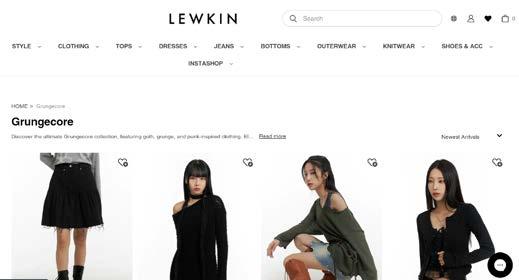

Figure 1 Screenshot of an e-commerce store with the search phrase grungecore 7

In social media, especially platforms like TikTok, the suffix “core” has emerged as a suffix to characterize specific aesthetics (Mendez II, 2023). This trend has evolved into a mass culture phenomenon, where almost anything can be labelled as a “core,” 1 (Mendez II, 2023).

To critique core, using grungecore as a focal point, it’s essential to establish that grungecore, and by extension “core” aesthetics, truly represent a mass culture phenomenon drawing on Strinati’s theories (2004), including a comparison of folk culture and mass culture using grunge and grungecore to illustrate the differences. Marx’s theory of Commodity fetishism (1867) will then be applied to show the transformation of grunge into commercially appealing and mystically enticing grungecore. Hall’s theories (O’Donnell, 2005) will be employed to contextualize grungecore within specific cultural backgrounds, exploring the negotiated decodings of its encoded discourse.

Mass culture is driven by the profit it can generate from its potential mass market (Strinati, 2004, p. 10). That is to say, a mass culture is “produced by the industrial techniques of mass production, and marketed for profit to a mass public of consumers” (Strinati, 2004, p. 10).

1 As seen in examples like frogcore, cottagecore, corecore, grungecore

Screenshot of an e-commerce store with the search phrase grungecore

Note: Lewkin, 2024

Mass culture is characterised by standardised and repetitive products that are known to work, and consequently, lack originality, innovation, and intricate aesthetics (Strinati, 2004, p. 11).

Grunge as a fashion aesthetic began in conjunction with the rise of the music genre’s popularity and was a nonfashion statement more than a fashion statement (Marin, 1992). Grunge fashion was cheap, second-hand, thrifted, and personally tailored and customised (Marin, 1992). These values of grunge, as it was, align with Strinati’s definition of folk culture; which necessitates operating beyond the confines of what is purely profitable and instead focuses on authenticity, as well as being produced by a socially consolidated community that knows what it is doing (2004, pp. 9, 11). Modern-day grungecore on the other hand aligns much more with Strinati’s mass culture as it is the result of the mass fashion industry taking grunge aesthetics and standardising them into products that are ultimately repetitive and lack complexity for the primary purpose of being marketed to the masses through commercial clothing stores to generate profit. For evidence of this see Figure 1 below, which showcases two almost identical jumpers in the first row of products alone.

According to Marx, a commodity is, simply put, a product that, by its attributes, is capable of satisfying human wants (Marx, 1867, p. 41). Marx goes on to elaborate that commodities are perceived as something transcendent and not something that simply satisfies wants (Marx, 1867, p. 41). A commodity no longer gains character from its use value, nor any quantitative measure of value, but rather the misguided belief that the form of a commodity has intrinsic value(Marx, 1867, p. 41). This belief masks the social relationships and labour processes

behind a commodity, allowing it to gain value solely related to its marketed appearance (Marx, 1867, pp. 41–42). This idea becomes especially crucial when applied to grungecore.

Grunge fashion historically had its roots in authenticity, dissatisfaction with capitalism, and rebellion against the norm (Davis, 2023). Grunge fashion removed emphasis from buying clothes with inflated prices, it prioritized going against industry and commercial trends, instead focusing on utilitarian, thrifted, and DIY clothing (Davis, 2023). Grungecore is evidence of the commodification of grunge fashion; what was once DIY or thrifted is now commercially consumable as a commodity with the myth of authenticity and rebellion attached to the item of clothing itself.

The commodification of grunge extends beyond singular items of clothing and encompasses the lifestyle and ideals of grunge. The selling of predistressed clothes, for example, that mimic authentic grunge fashion (Bramley, 2017) allows brands to capitalise off of grunge’s anticonsumerism, while simultaneously masking the social relationships and labour processes behind the commodity, as Marx stated is characteristic of the fetishism of a commodity (1867, p. 41). It is also noteworthy that the fetishisation of grunge serves to depoliticise grunge and to slow its subversive nature. Grunge once represented a stand against mainstream consumerism, whereas grungecore now has turned that symbol of rebellion into a commodity to be consumed. In these ways, commodity fetishism is present in the world of grungecore fashion.

According to Hall, a discourse calls out to a viewer, to answer this call the viewer must recognise they are being called out individually (O’Donnell, 2005, p. 527). Representational codes are sorted into social acceptability by ideological codes such as individualism, patriarchy and materialism (O’Donnell, 2005, p. 531). The messages are encoded into discourses with a

preferred meaning that supports and reinforces a certain ideology (O’Donnell, 2005, p. 531). Decoding these encoded meanings is dependent on personal context (O’Donnell, 2005, p. 527).

For that reason, to apply Stuart Hall’s encoding/decoding model to grungecore, a contextual culture must be identified. In this particular instance the cultural context of a white male, design student in South Africa will be used to discuss the theories of Hall. As briefly discussed, grungecore markets the ideas of grunge. Therefore, the encoded message within the marketing and discourses around grungecore follow the lines of “buy this and be a rebel” or “buy this and show you are unique” and repeated with adjectives such as nonconformist, antiestablishment, anticapitalist, and so on. These messages support two major ideologies; consumerism and individualism.

The decoding of these messages in the cultural context established earlier results in a negotiated position. Negotiated is defined by Hall to fit viewers who primarily fit into the dominant ideology but need to resist certain elements of it (O’Donnell, 2005, p. 528). In the culture identified, the message of individualism encoded into grungecore is likely to be dominated; the meaning is accepted fully. This is because artists and creatives tend to want to separate themselves from what is the norm and display an element of uniqueness, and adopting these messages and ideals would assert identity within the artistic community. The resistance required for the decoding to be negotiated comes from the message of consumerism. The world of art and design, especially among younger students, has a strong culture of experimentation, DIY and self-expression. In addition to this, these students are often very aware of concepts such as Americanisation, as well as the potential dark sides of capitalist society. For these reasons, in the culture defined, consumerism may be rejected

on the principle of standing against Americanisation and the perpetuation of unjust labour. Resulting in the final decoding of the discourse being negotiated.

Through the arguments made, grungecore was first established as an example of a mass culture phenomenon, using the theories of Strinati. This was accompanied by the comparison of grunge as folk culture and grungecore as mass culture. The commodifying of grunge into grungecore was then discussed using Marx’s theories of commodity fetishism. The transformation of what grunge stood for into an easily consumed commodity, that sells the mystical idea of rebellion to conceal the product’s labour processes. A specific culture is defined to then contextualise the decoding of the ideologies encoded in grungecore. The critique applied to grungecore applies to any aesthetic labelled as ‘core’, not every core aesthetic may have the history of grunge, but each one represents the fetishisation of commodities for profit.

Bramley, E. V. (2017). Distressed fashion: Making sense of pre-ripped clothes. The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/fashion/2017/aug/18/distressed-fashion-making-sense-of-preripped-clothes

Davis, R. (2023, March 11). Grunge Fashion: The History Of Grunge & 90s Fashion. https:// www.rebelsmarket.com/blog/posts/grunge-fashion-where-did-it-come-from-and-why-is-itback

Marin, R. (1992, October 15). Grunge: A Success Story. New York Times. https://www.nytimes. com/1992/11/15/style/grunge-a-success-story.html

Marx, K. (1867). The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret Therof. In Capital A critical analysis of capitalist production (pp. 41–56). SWAN Sonnenschein.

Mendez II, M. (2023, January 20). What to Know About Corecore, the Latest Aesthetic Taking Over TikTok. Time. https://time.com/6248637/corecore-tiktok-aesthetic/

O’Donnell, V. (2005). Cultural Theory Studies. In S. Josephson, J. D. Kelly, & K. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of Visual Communication: Theory, Methods, and Media (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429491115

Strinati, D. (2004). An introduction to theories of popular culture (2nd ed.). Routledge.

© 2024 The Open Window