Your literary dose.

Your literary dose.

© The Opiate 2022

Cover art: Photo taken outside of Petit Palais, March 2022

This magazine, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced without permission.

Contact theopiatemagazine@gmail.com for queries.

“...in an era popularly described as ‘post-political,’ class war has continued to be fought, but only by one side: the wealthy.” -Mark Fisher

The Opiate, Fall Vol. 31

Editor-in-Chief

Genna Rivieccio Editor-at-Large Malik Crumpler

Editorial Advisor Anton Bonnici

Contributing Writers:

Fiction:

Alan Gartenhaus, “The Outing” 10 Ed Davis, “Angelina” 14

Nik Ruckert, “Queen Jane” 27

Steve Fromm, “Good Morning, Mr. Mansfield” 30

George Kuchinsky, “My Goliath Is Internal,” “A Wash of Birds” & “Late Harvest” 46-48

Margaret Wagner, “Looking in the Mirror” 49

Matthew Peluso, “An Ode to Evil” 50-51

Donna Dallas, “If It Took Us Down Then, What About Now?,” “There Are Two Poems In This” & “Flashbacks” 52-57

Yuan Changming, “Etymology of Family,” “Simplification of Chinese Characters Reviewed” & “Neighbor’s Garden” 58-60

Antonia Alexandra Klimenko, “Taxidermy” 61-62

Xavier Jones, “Eulogy for Priam,” “Voices,” “Ingratitude,” “The Vandal” & “Price Tag” 63-67

Dale Champlin, “Shopping With Zombies” 68

Zeke Greenwald, “The Butcher’s Complaint” 69

Anna Kapungu “Masquerade” 70

Genna Rivieccio, “The Writer As Main Character: Elizabeth Hardwick’s Sleepless Nights & Eve Babitz’s Sex and Rage” 72

The intent in this society has always been to make those who question and resist “the norm” feel like they are mad (yet, as the Cheshire Cat once told Alice, “We’re all mad here”). That there is no place for them because they’re the crazy ones, not, oh, maybe the system firmly in place designed to perpetuate a cycle of poverty for those who are trapped in it. And poverty, in the current epoch, essentially amounts to just about anyone who isn’t in the one percent. It takes literal gobs upon gobs of money just to exist at a baseline level, and it isn’t getting any better. Nor is it going to. Hence, the existence of a phrase like “eugenics of the poor.” Meaning that it is patently the intention of the rich to keep the cycle of poverty in place so that no subsequent generations of those born to poor parents (which, again, is a pretty all-encompassing term at this juncture) will ever be able to break out (break “free” sounds entirely too hyperbolic). In turn, a “race”—since class is synonymous with that word as well—is essentially stamped out.

But what actually happens is that a new “breed” crops up in its place. One that is meant to be “stronger” a.k.a. capable of enduring more shit (while suffering in greater silence) from the proverbial Oppressor. When looking back at eugenicists who genuinely did see poverty as a “trait” that could be “eradicated,” it’s a wonder they didn’t pick up on the fact that, after the passing of so many generations, the existence of poverty is not only still very much “alive,” but has spread like a disease even to those whose forebears could have once been deemed middle-class. And yet, at the height of “social reform” in the United States, the poor were lumped in with the handicapped, both sects of the population being placed in “institutions,” failing a family or community member present to help care for the person in question. Obviously, it didn’t take long for such institutions to experience major “overflow.” To the point where it was apparent that the government and its various assistance programs were being far too “generous,” and that, instead, society ought to just let those who couldn’t “do” capitalism

go the “San Francisco route,” if you take one’s homeless-oriented meaning. Or, to be more flowery about the “phenomenon,” the sans domicile route. Very polite. And one might argue that the true reason behind the politically correct police pushing to eliminate the word “homeless” in favor of more “pleasant” language, like “people without housing,” is because a phrase such as that allows us to believe that, one day, if a homeless person works really hard and licks Capitalism’s asshole, they might be able to get a fixed residence again. Naturally, no one wants to account for how the vicious cycle of poverty simply won’t allow for that. No matter how many “golden opportunities” or “legs up” might be given by those who think “people without housing” are just being “lazy” at this point if they can’t “make something work.”

Alas, anyone who is not born into generational wealth is probably going to have quite a bit of trouble making it “work” (sometimes vexingly referred to as “doing the best with what you have”). Case in point, look at any person you see flashing their ass for the cash, so to speak, today. More often than not, a number of “gigs” are required to even quote unquote function (read: buy groceries regularly and afford rent). And yet, for those at the top, there is no “making them understand.” Empathy, if any such quality is even capable of being present in the rich, can only come from being subjected to the same shitty, rigged experience. Take, for instance, Madonna’s character in the oft-panned Swept Away. As quintessential rich bitch Amber Leighton, she is immune to any cries of “unfair” about capitalism, insisting to Todd (Michael Beattie), one of the “friends” she’s on a private cruise through the Mediterranean with, that there should be no sense of guilt about, say, a pharmaceutical company jacking up the price of a cheaply-made drug that could, for example, cure blindness.

She seethes to Todd about his attempt at empathy for the “less fortunate,” “What’s to stop them [for the rich are even more “us v. them” than the poor] from getting a job and buying the drug?” He looks at her in awe, incredulous that he has to spell it out: “They’re blind. That kind of limits their employment opportunities, doesn’t

it?” “Well, they can bake cakes or something. You don’t need eyes to bake cakes.” Just like, sure, you don’t need to start out having money already in order to amass more of it. But Amber, in her rich woman’s tunnel vision, can only snap back, “The laws of capitalism are: the proprietor of goods can set any price he or she sees fit and shall not be held at the mercy of any moral or ethical issues.” Meanwhile, the yacht’s deckhand, Giuseppe (Adriano Giannini, whose own father, Giancarlo, played the role in the original Lina Wermüller version), overhears her callous approach to “doing business.” Never would he have dreamed that he could pay her back for such coldness by later using her own words against her once they get stranded on a deserted island. As a result, she is presented with the previously unknown reality that her money means nothing here, yet she still offers to buy a fish from Giuseppe that he catches himself (she possessing no such skills to do so). But no matter how high she sets the price, he won’t accept the bid. That’s his prerogative as a “proprietor,” per Amber’s own “rules.” The ones she would never want applied to herself. So it is that he then taunts, “If you’re hungry, bake a cake.”

One can only fantasize about the day such sweet revenge might happen for all the working-class as a means to make the rich understand how fucking frail they actually are without the laboring population on their side. Not that it even is to begin with—they’ re simply caught in the vise grip of capitalism and “needing” to make money (despite it being a social construct) solely for survival.

“There are some things in life that can’t be bought,” Giuseppe declares as a conclusion to their exchange in this scene. Though, sadly and for the most part, they can be. Increasingly so, as a matter of fact. Most troublingly of all, in the realm of art, where everyone has a “platform” for sale through which “artists” can peddle their wares, AI-generated or otherwise, if they have the means to pay for such valuable publicity.

Your caught-in-the-capitalist-trap comrade,

Genna Rivieccio October 31, 2022

Alan Gartenhaus

Alan Gartenhaus

CaféPierre looked like an old country cottage––dark wood beams and red brick, with French doors that opened onto the sidewalk. Jayson walked toward it, stomach in knots, telling himself to continue past if he felt uncomfortable. He had assumed the bar would be clandestine, like speakeasies he’d seen in movies. He never suspected that it would be as public, or as quaint.

He’d only learned of the place days ago. Friends had made snide comments. None of them knew about him, of course. No one did. He’d never said anything to anyone.

Jayson had been told that those “afflicted” were sinful, de praved, and dangerous––and while he think didn’t think of himself like that, he understood that others would. He had no one to confide in, and no role models to consult. His family’s church offered no refuge; his parents referred to such people as abominations.

Standing outside the doorway, he peered into the bar’s dim ness and saw a heavy-set man wearing a straw boater as he played the piano. A hurricane lamp glowed on the instrument’s closed lid, its soft light complementing what seemed a relaxed atmosphere. As he stepped forward to get a better look, an elderly, hollow-cheeked waiter greeted him and, with a slight nod and the sweep of a bony brown hand, invited him to sit wherever he wished. Jayson threaded a path to the other side of the room, as far from the open doors as possible.

He fixed his gaze on the gas fireplace that flickered nearby and the liquor bottles behind the bar, glinting like Christmas ornaments. He understood that being there had momentous consequences, although exactly what they were remained a mystery.

A different waiter, this one dressed in a white jacket and bowtie, approached his table. “Forgive me, but I’m required to ask how old you are.”

“Twenty-two,” Jayson replied. He’d often been told that he looked younger than his age.

“May I see an ID?”

He removed his driver’s license from his wallet. The waiter used a small flashlight to read it. “What may I get you?”

Jayson glanced at a hand-lettered chalkboard touting several cocktails as specialties of the house. “I’ll have one of your Coco Locos, please.” He liked the name.

“Just to let you know, there’s a cover charge. It includes a second drink.”

“Do I order both now?”

The waiter chuckled. “No. You can wait.” He set a few cocktail napkins and a paper coaster on the table before turning and heading for the bar.

Though tempted to ask how much the cover charge would be, Jayson knew it wouldn’t matter. He would stay, regardless. He took a few deep breaths and blotted the rivulets of perspiration rolling down his sideburns with one of the napkins. When the waiter returned with an oversized, ceramic coconut shell adorned with a pineapple slice, a cherry and mint sprigs, Jayson laughed, embarrassed by its appearance. “It’s more potent than it looks,” the waiter said with a smile as he set the drink on the table. He put a small bowl of salted peanuts beside it.

Jayson tapped his fingers to the spirited piano music. The piece sounded familiar. Jazzy. Fun. The type of tune that has witty rhyming lyrics. He tried to recall where he might have heard it before as he pulled a swallow of the frothy cocktail through its colorful straw, the

taste sweet, like a dessert. It went down easily.

As he sipped, he wondered how a romantic encounter could be initiated here. Would someone approach and offer to buy him a drink? He couldn’t imagine himself being bold enough to take such an initiative, no matter how much he might have wanted to, worried that it could get him punched in the nose. He’d had a crush on a guy who’d lived in his neighborhood––dark hair, sapphire-blue eyes––but could barely speak in his presence. That hadn’t stopped him from fantasizing.

The waiter slowed the next time he walked by. “Ready for that

second one?” he asked. Jayson nodded. “The same kind?” Jayson smiled in reply. He felt a lessening of tension in his neck and back, along with something akin to mild sleepiness, the sensation quite pleasant.

When the second drink arrived, Jayson told himself to go slow, but the sultry evening air and nervousness defeated that. Curiosity got the better of him, too; he looked around, surveying the other customers. Everyone seemed rather sedate. He saw no cross-table talk, so when a good-looking fellow at the table next to his leaned over and said, “He’s great, isn’t he?” Jayson was taken by surprise.

“Who is?” Jayson inquired, his heart beating faster.

“Milo, the man on the piano.”

“Oh, yes. He’s pretty good.”

“Pretty good? He’s one of the best.”

At that moment, the waiter returned and set a glass of water in front of Jayson. “Thought you might want some of this.” He gave Jayson a cautionary look.

Ignoring the waiter’s suggestion, and concerned that the intrusion might have derailed his conversation, he turned toward the man beside him and said, “Guess you’ve been here before.”

“Many times,” he replied. “I always try to come when Milo plays. It’s not often you get to hear someone so accomplished. Isn’t that why you’re here?”

“Uh, sure.” Jayson took a swig of his cocktail. He felt lightheaded. “And to meet someone.” He couldn’t believe that he’d just said aloud what he’d been thinking all night.

The man smiled and turned his attention to his straight-up martini.

Jayson extended his hand. “I’m Jayson.”

“Hi, Jayson. I’m Bill. So, who are you here to meet?”

Jayson took another swallow of his Coco Loco. “How about you?” He thought his response clever.

“My wife,” the guy said. “She should be walking in any minute.”

“Your wife? You’re married?”

The fellow retrieved the olive from his martini and ate it. “Six years now,” he said.

“And she’s okay with your being here?”

“She loves Milo even more than I do.”

The alcohol had overwhelmed Jayson’s restraint. “And she doesn’t mind going to a gay bar?”

The man’s eyes widened. “A gay bar?” He shook his head. “You must be thinking of Café Pierre in Exile. This is Café Pierre. That bar is a couple blocks further down the street.”

Jayson’s face grew flush. He nodded, settled back in his chair and listened to the pianist sing Gershwin’s “They Can’t Take That Away From Me.” Instead of requesting the check on the waiter’s next pass, he asked for a ginger ale. This evening, he decided, had been a dress rehearsal. He might not be going to that other bar tonight, but he would someday soon. Maybe even tomorrow.

“The Outing” was originally accepted for publication by Living Springs Publishers

Of all deceivers fear most yourself!

—Søren Kierkegaard

You were never in love with me.” My wife was snapping the latches on her turquoise Samsonite as I watched from the corner of our bedroom. “It was the idea of me that you loved.” Her voice, ragged from the shouting, scraped raw from the anger, was hollow now. “I can’t be your idea anymore.”

I knew she was right, had known it from the beginning. Fishin’ way beyond his depth, I’d heard a friend say when he thought I was out of earshot. We were small-town celebrities. She was O’Farrell royalty, I was its best-known writer—Arthur Miller to her Marilyn Monroe. Our coming apart felt anything but small.

I thought I loved her.

But in the weeks after she left, I began to realize that it was wor ship, not love. My pedestal was a poor fit for her perfectly manicured feet. She did her best to find her balance, for the better part of three years, but needed a steadying hand that I seldom offered.

It was the idea of her that I worshipped, and I did not want that

image marred by something as imperfect as intimacy.

Intimacy. My Webster’s defines it as Something of a personal or private nature.

Personal or private.

We shared a home. We shared a bed. I studied her every contour like a surveyor mapping Eden. She eventually understood— understood before I did—that my desire to know her stopped there.

I wondered, could I capture in words what I had been unable to capture in life? There could be no idealizing. Honesty. No cruelty.

Angelina Tognazzi was a senior when I was a freshman. She was, at that time, the heaviest person I had ever seen. If every school has a required quota of types, Angelina was O’Farrell High’s fat kid. Wherever she moved in the halls, in the cafeteria, anywhere, a wide zone of untouchability seemed to surround her. You couldn’t miss Angelina, and couldn’t help but see, if you paid any attention, that what she wanted most was to be missed.

If she had friends on campus, I never saw them.

If she smiled, I never saw that either.

Angelina’s parents owned Tognazzi’s Hardware, a store I sometimes shopped at, and where Angelina had worked behind the counter for the ten years since graduation. Though I had never spoken with her at school, we sometimes exchanged a word or two at the store.

Other than the obvious, I knew nothing about her, no more genuine intimacy between us than between me and my wife. It was that realization, I think, that planted the idea.

I would need to protect Angelina. The hardware store would need to become something else, maybe a deli.

And I’d need to find another name...

On the outside wall of Wiggins’ Country Store—the wall that faced the cannery across the street—was a large painting of a large woman, Mama Wiggins. She stood with a hero sandwich in hand—you could get a hero in the store—and a toothful grin flashing through the folds of a large, languid face. Except for size, the painting was a poor

likeness and could have been any one of the three Wiggins women. Mama, big sister Julie and little sister Gabrielle all shared features with the grinning mural. Same color hair, same toothy smile, same immense body.

Were the three ladies ever to have crowded onto the apple scale at the cannery across the street, their combined weight would have exceeded a thousand pounds.

Gabrielle Wiggins watched the store every day from noon until six o’clock. Mama took the duty each morning, and big sister Julie closed out at midnight. It was a small, simple store with a cooler for beer and sodas, the cold counter where sandwiches were made, a few aisles of canned goods and snacks, and a cash register. A gas pump out front was hardly ever used—gas was a nickel more a gallon than at the regular stations, and the big ladies took so long to pump it that few wanted to wait. All the stocking was done by a high school boy who came in for a few hours each afternoon. The women were so large they could neither reach up to the higher shelves, nor bend down to the lower ones.

Gabrielle was both the youngest and lightest female member of her family. Only twenty years old, she weighed in at three hundredfifteen pounds, dainty compared to Julie’s three hundred-eighty or Mama’s four hundred-plus. Though it was difficult to tell beneath the excess skin that obscured the shape of her cheekbones and the cut of her jaw, Gabrielle was also the prettiest. She had a beguiling smile, a soothing voice, but the rest—turn of ankles, curve of calves, flare of hips—could only be guessed at beneath her standard camouflage, a muumuu that concealed the tree-stump legs, the moving mound of collected fat that rode on each of those hips, the gallons of flesh that hung from her chest.

Gabrielle would have hidden her entire body from the world if possible, but a muumuu was the best she could manage. Like a tentcovered giant, she lumbered about the store each day from noon till six o’clock, making sandwiches, selling gas, and wishing she were someone else.

Most of the store’s business came from the cannery workers across the street. Between shifts and at breaks, the store was full of dirty, boisterous men smelling of apples and sweat. Because of her youth and size, Gabrielle worked the midday shift. Her mother and sister were so large that they could not move rapidly enough to handle the crowd during lunch, or the incoming and outgoing tide during the

three-thirty shift change. Even for Gabrielle, it was hard. The sandwich counter and cash register were at opposite ends of a twenty-foot aisle, and she constantly had to shuttle between them, huffing back and forth so quickly that, by the end of the rush, her muumuu would be drenched, her thighs chafed. If she hurried too much, the weight of her footfalls on the old wooden floor would set items rattling on their shelves as she passed.

In the midst of one such rush, Jody Blanchard came into the

store. He was the valedictorian of Gabrielle’s class, and Jody had been a friend to her. She had other friends in school, but none like Jody. He was slim, attractive, played sports and acted in the school plays. The Wigginses and the Blanchards lived in the same part of town.

Through all the years they were in school, Jody and Gabrielle had been pals. More than once, Jody stood up for her when other kids made fun. And more than once, Gabrielle wished that she were as slim and attractive as the other girls, the ones Jody liked in a different way.

On the night of high school graduation, Jody put his arms around her and kissed her.

For that one moment in her whole life, she did not feel like a fat girl.

And now, two years later, he was standing across the sandwich counter.

In a hard hat and overalls, he looked like the other men in the store, but Gabrielle knew it was Jody right away. Since graduation, she had looked at his face again and again in the thumb-smudged pages of her yearbooks and in her mind.

For two years, each time she heard the screen door swing, she looked up, wishing without any real hope that she might see him there.

“Salami and Swiss with just mustard, and make it quick, dollface... That horn’s about to blow.” A small man, probably in his forties, was first at the counter. Gabrielle did his bidding without reply. Slice the French roll down the middle, plaster mustard on both pieces with the spatula, add a few slices of Swiss and a handful of salami, wrap it in wax paper and on to the next one. She liked to let four or five customers build up at the cash register before making the trek. The small man with the salami and Swiss would be the fifth.

But Jody was next in line.

“Hi, Gabrielle.” The same voice, same blue eyes, same smile. “Is it always hoppin’ like this?”

“Just around lunchtime, and around three-thirty.” It was Jody all right. For as long as she could remember, he was the first person who cared if she was busy. “How are things at college, Jody, and with the scholarship? I was so happy when you got it.” Someone at the cash register cleared his throat. She was keeping them all waiting. “What kind of sandwich can I make for you?”

“Whatever’s easy.”

“How about ham and cheese with mayonnaise and mustard on a sweet roll?”

“That sounds fine.”

She went about preparing the sandwich, taking extra care not to slop mustard and mayonnaise on her hands. While she worked, Jody talked.

“I guess I’ll be over here every day for lunch now. Just signed on at the cannery, and the guys tell me I can’t get a better sandwich anywhere in town.” She smiled at the compliment, and thought about how she’d start doing her hair differently if he would be coming back every day. “That scholarship was great, but about halfway through my second year at State, I decided I needed a break…figured I’d try some manual labor for a change.”

“What about all your plans?” Since they were kids, Jody had talked about wanting to be a lawyer. Gabrielle imagined the day she

would read of his exploits, read that Jody Blanchard had won another case. “You’re not giving up law school, are you?”

“Not giving up, just settin’ it aside for a while.” There was another noise from one of the men at the cash register. “Sounds like you’d better get down there.”

She nodded and they both headed toward the front of the store, his sandwich cradled in her hands.

Usually with a crowd at the register, Gabrielle would rush down the narrow aisle, swinging her hips dangerously from side to side, sometimes bouncing canned goods off the shelves as she went. This time, as smoothly as is possible for a three hundred-fifteen-pound woman, Gabrielle glided through the store, Jody beside her just across the long counter.

They smiled at one another as they walked.

The crowd at the cash register was muttering, approaching anger, their impatience inching toward ugliness. As Gabrielle and Jody neared, the small man with the salami and Swiss nudged a companion and said, just loud enough to be heard, “Look at the meat on that woman. A guy could play with that all day and never cover the same ground twice.”

Jody bristled.

Gabrielle went on as if she hadn’t heard.

One by one, she took their money, handed them a sandwich. When the small man came up, he winked and made sure that his hand touched hers as she gave him change. She pretended not to notice, but something about his touch and his look refused to be ignored, like gum on the bottom of a shoe.

In a few minutes, she and Jody were alone in the store, the rush over. Her muumuu was soaked through, but Jody was there.

“I thought that kind of crap stopped back in grammar school.” His cheeks were flushed.

“In grammar school it stopped because you were there to stop it. Now people say whatever they like, but I don’t pay any mind.”

She did mind, and couldn’at look at him as she told the lie.

It was then that he reached out and touched her, just a light stroke of her cheek. When she felt his hand, tears filled her eyes. She wanted to look up, to reach out—to touch him.

She couldn’t.

The shrill call of the one o’clock whistle broke the silence.

“Oh Christ, I’m late and it’s still my first day on the job. Okay if I pay you for the sandwich later?”

“Sure, Jody, sure. You can pay anytime.”

“Great, I’ll see you in a few hours. Bye Gabi.”

No one called her Gabi, no one but Jody.

In a rush he was out the door, sprinting across the street. She went to the window and watched him weave between cars in the cannery parking lot, her hand touching her cheek where he had touched it. Tears came again, and ran in wide streaks down the front of her face and onto her already wet muumuu.

When a car pulled up to the gas pump a few minutes later, it honked twice before she heard.

***

The hours between noon and three-thirty never went quickly for Gabrielle but never slower than now. This afternoon she could think of nothing but Jody—his eyes, his touch. She had been in love with him since they were kids, the kind of love that feeds your heart even as it breaks your heart, the kind that fearlessly protects the best part of who you are, whether or not the love is ever returned.

Now she loved him more.

She spent those long afternoon hours picturing how it would be when Jody came back. Where would she be standing? Who else would

be in the store? She thought it best if she was behind the cash register, and if no one else but the stock boy was there. Yes, the stock boy should be there and within hearing distance so he could repeat everything to Mama and Julie.

That way, she wouldn’t have to tell them a thing.

Because Jody would want to be alone with her, he’d wait until after the three-thirty rush. He’d be tired from his first long day’s work. She would talk to him, comfort him, maybe invite him over for dinner. When they were kids, he used to come to her house for dinner all the time. Only now, she would do the cooking instead of Mama. She’d bring home a six-pack and some big steaks. She’d tell Mama to work late at the store with Julie. Mama might complain but she wouldn’t fight—Gabrielle was not only the youngest and lightest member of the family, she was also the toughest.

Again and again, she played the scene with Jody. The words they would say, the way it would look, the wonderful way she would feel. A six-pack of beer, some big, thick steaks and a whole evening alone with Jody Blanchard. She didn’t carry the scene past dinner. Simply being alone with Jody was more than she had a right to hope for.

Anything else was impossible…or was it?

At two-thirty, the stock boy showed up, and at three o’clock the swing shift workers began to come in. These were men who wanted a sandwich or a beer before beginning their evening’s labor. It was busy, but Gabrielle refused to work herself into a sweat. Not today, when Jody would be coming back.

She set the stock boy to making sandwiches while she worked the register.

It seemed an eternity before the three-thirty whistle sounded.

The few swing shift men still left in the store hurried out, and for a moment the place was empty. Gabrielle noticed the stock boy standing behind the sandwich counter. With a stern look, she sent him back to work on the shelves.

At that moment, the day shift began to filter in.

Any minute, Jody Blanchard would be walking through the door.

There was never a rush after the three-thirty whistle, just a trickle of tired men looking for something to slake their thirst or feed their sweet tooth on the way home. One by one they walked past her, not knowing as they paid for their items that the girl seated on the stool behind the register wasn’t aware of them at all. Gabrielle wasn’t seeing

anything but the scene she had been playing and replaying in the quiet hours of that afternoon, the best hours she’d known in two years. Three-hundred-and-fifteen-pound Gabrielle Wiggins had ceased to exist.

Though her body still sat behind the counter, her soul, slim and delicate, lay wrapped in the arms of her lover.

When Jody came in, it was just as she’d imagined. No other customers were in the store, and the stock boy was busy filling shelves, but near enough to hear everything that was said.

She watched him walk through the door, and tucked a wayward strand of hair behind her ear—hair she had fussed over in front of the splotched bathroom mirror. It was a mirror, like all mirrors, that she rarely looked at. But today was different. As he approached, she touched her face lightly, just where he had touched it. She needed to be sure that this was truly happening, and not just another repeat of her dream.

“Hey, you fixed up your hair,” he noticed, and she blushed. “Thanks for letting me dash out like that. The foreman did give me hell.” He dug into his pocket and produced money for the sandwich. “I almost forgot to come back and pay.”

“When his eye caught hers, he flashed a smile that made her want to look away. She didn’t. She felt empty inside, as if she had just vomited a piece of her soul, but she forced herself to smile back.”

When he gave her the bills, their hands touched.

“You look tired, Jody. Was it a hard day?” She still couldn’t believe that it was all going exactly as she’d imagined it. He did look tired.

“Hard enough.” He took his change and their hands brushed again. “The work’s not so tough, but on the amount of sleep I’ve been getting, it’s a job just to stay awake for eight hours.”

“You are still studying. I knew you wouldn’t give it up.” This was even better than she’d pictured. He could tell her all about it over dinner.

“I’m studying all right… I guess you could call it that. You remember Carol Hopkins? She’s keeping me busier than sixteen units ever did.”

“You look so tired, Jody,” she noted again, trying not to think about Carol Hopkins. She was one of those girls Jody liked in a different way. The daydream was crumbling, but there was still a chance. “Tonight, why don’t you come to our place for dinner? I’ll cook you a nice steak. You could sit back on the sofa, drink a beer, relax. We could catch up.” She didn’t meet his eyes, didn’t dare pause, hoping that, in saying these things, she might make them come true. “You’d like it, I know you would.”

She wasn’t just offering him dinner; she was offering him everything. Did he know that? Did he understand?

Though afraid to look up, she knew she had to. His smile was there, the tender smile of the boy she loved.

“I don’t know the last time I had a quiet dinner with a really good friend.” His hand came up and touched her on the cheek again, so lightly she could hardly feel it. “But I’m afraid I can’t. Carol’s got me so booked up these days, I hardly have time to think. I guess that’s what being in love is all about, isn’t it?”

Gabrielle knew what love was about. She knew, and wanted to tell him.

But she felt doors slamming shut inside her, doors that had only opened that afternoon. Doors that might never open again.

The realization made her voice a prisoner.

Words could not escape the ruin of her heart.

A car pulled up to the gas pump, a sleek white sports car with a sleek white girl at the wheel. From the driver’s seat, she peered through the screen door, saw Jody standing by the cash register and began honking, calling his name.

To Gabrielle, the girl’s voice and the blaring horn sounded just

The Opiate, Fall Vol.

the same.

“Look who’s here.” He waved and the honking stopped. “Don’t even have time to pass a few words with my best girlfriend.” He moved as if to touch her again, but something in Gabrielle’s eyes changed his mind. “I’ve got to scoot, or Carol will get jealous. Thanks for the dinner invite. I’ll take a raincheck for sure.”

Then he was gone.

This time, Gabrielle did not get up and watch him leave.

She didn’t do anything but sit behind the cash register and feel her body grow.

***

It was an hour later, just after the stock boy went home, that the man with the salami and Swiss came back in. He was still dressed in his work clothes, but now smelled of whiskey instead of apples. From the moment he entered the store, he did not take his eyes off her. She tried to ignore it. She couldn’t. He moved about the aisles, picking things up, putting them back in place, but always watching.

When his eye caught hers, he flashed a smile that made her want to look away. She didn’t. She felt empty inside, as if she had just vomited a piece of her soul, but she forced herself to smile back.

He came over to the cash register with a candy bar in his hand, took a twenty-dollar bill from his pocket, wrapped it around the candy and handed it to her.

“Don’t you have anything smaller? This candy bar’s only a nickel.”

“I’ve got lots of nickels, honey, but I want twenty dollars’ worth of candy.” She’d had propositions like this before, and they always terrified her. For the longest moment, there was complete silence; even the cannery across the street had gone quiet. “Doll, you’re the biggest candy bar I’ve ever seen.” He looked nervously around the store, then took a pint from his hip pocket and drank. “What do you say? Put the sign up and we’ll have at it…don’t need no bed, the floor’s just fine. You and me’ll shake these shelves for sure.”

He handed over the pint and she took it.

The hot liquor slid down her throat. The “Closed” sign went up in the door.

She had told herself it wasn’t supposed to be like this, but maybe she was wrong. Maybe dreams are always what others can’t give you, or you can’t give yourself, and life is what’s left.

Maybe that, whatever it is, has to be enough.

The floor behind the sandwich counter creaked beneath their weight.

Gabrielle had never made love before, and with the drunken man groaning on top of her, she understood that she never would. Love was for a slim, graceful girl in her boyfriend’s arms.

She was not that, and never would be.

When it was over, she heard the door close after him. She felt his leavings, a viscous insult, oozing down her thigh.

She lay there, eyes clamped shut. Although Gabrielle had just been physically closer than ever before to another human being, she had never felt so utterly alone.

***

I had done it.

I was proud of what I had written, of the struggle to step outside myself to create so visceral a connection. The experience was both exhausting and unexpectedly satisfying. Yes, I could empathize with another human being, one as different from me as my wife was from Gabrielle.

And before I had written the last words, I also understood that I had fallen in love with Gabrielle Wiggins. Not the idea of her, but her. Unlike with my wife, it wasn’t because I didn’t know private and personal things about her, or that I didn’t want to.

It was because I did.

The story’s acceptance by our local literary journal felt like affirmation that I was not a heartless bastard after all.

***

Though I had hoped to mask the identity of the woman Gabrielle was based on—Angelina had no sisters, and her mother was a little wisp of a thing—I am certain that at least one person did make the connection.

The most succinct review I would ever receive came a few weeks after publication, when I was picking up supplies at Tognazzi’s. For as long as I’d known Angelina, I’d been guilty of viewing her as a thing, as an idea, just as I had viewed my wife.

The story had changed all that.

If this was not intimacy, it was as close as I had ever come.

When I approached the counter through the crowd of shoppers, there was Angelina sitting behind the register, big as always but somehow more present, more real in my eyes. I could see immediately that she was looking at me, staring at me. Maybe she had done this before, but like so many other things about her, I had not seen it.

“You’re the writer, aren’t you?” She ignored everyone else in the store, exactly as the Gabrielle of my story had ignored everyone but Jody.

“Hi Angelina. Yes, I am.”

“Go fuck yourself.”

She drew back, like she was about to throw a punch, then lunged forward with startling speed and spat.

A big, wet gob stuck to my cheek, right where it hit.

The impact of her unmistakable words, her unexpected action, pushed a shockwave of silence through the store.

I was sure I loved Gabrielle Wiggins.

I was sure I had loved my wife.

Now, as if witnessing the scene through my wife’s and Gabrielle’s eyes—not through the conceited myopia of my own—I watched myself watching Angelina Tognazzi rise proudly from her stool, turn her back and walk away.

I felt the weight of her viscous insult hanging from my face like a badge of dishonor, glistening there in the harsh store lights for all to see.

“Angelina” originally appeared in The Atherton Review

She pulled the hem of her short nightgown down as far as it would allow, fingered a Queen Jane cigarette out of the pack, and lit it right off the gas stove. As the cigarette hung out of her mouth, she lowered the flame under her oatmeal with one hand and ran the thumb of her other across the raised crown logo on the front of the crush-proof cigarette box before dropping it into a heart-shaped metal ashtray, still dirty. Making her way, barefoot, across the small living area—filled with over six piles of books, three shoes and two cats—she managed to enter the bathroom: the only space in her apartment with a mirror.

She stood in front of the sink and, letting the hanging cigarette in her mouth remain there, broke out into a careful, wide smile. She lifted herself up on the edge of the counter and sat there, resting one foot on the toilet lid, the other up on the tank. She was too close to the mirror, what was she thinking? So she got down again. She wanted to see the full effect. She stared at herself and said, “Look, there’s no need to get so hysterical. It’s happened to me before, okay? I mean, I was just recently on the receiving end of it, like you are now. This sort of thing happens, you know. It’s not a reflection on you. Something is just miss-

ing, as it sometimes is with two people. Believe me.”

Then she paused.

“I’m the type of person, you should know this by now, who sticks to a decision once she makes it. I know I might not have demonstrated that so great with you the first time we broke up. Okay, that’s right, the first time I broke up with you, if you have to be so particular about it.” She exhaled a long train of smoke up onto the mirror. “Anyway, it’s the truth. I’m just so overwhelmed with everything. With school and

everything. Yes, I suppose if I wasn’t in school, maybe. But I am, and it’s—no, no, there is no other boy. There is no other boy. That’s got nothing to do with it. Listen, I love you so much I could cry: that’s also the truth. Did you know that? I could cry. I just really need you to be my friend right now. We do well when you’re my friend.”

She drew on her cigarette again and backed up further so she was flush with the wall. “Oh yes, I know I’m making a big mistake. It’s devastating to me. Pulverizing.” She threw her head back quickly and returned it to position. “I can hardly breathe. I’m very serious about you. I tried to be careful, but some things you just can’t control. It’s the way I feel. I know it’s hard for you. It’s very hard for you. This happens to me. I become a very big deal to the boys I’m involved with. Oh, you had it your mind to marry me someday, I know. And maybe we will be married someday.”

“I’m the type of person, you should know this by now, who sticks to a decision once she makes it. I know I might not have demonstrated that so great with you the first time we broke up...”

She leaned forward and tipped her cigarette ash into the sink. “Don’t you give me that.” She gazed briefly into the mirror. “You can’t act like I owe you something because of our peculiar situation. I don’t, I’m afraid.” She paused and looked up at the ceiling. She slowly turned her head side to side, stretching her neck. “You got into this too and I can’t exactly be held accountable, you know. And with my classes and all, everything is rising—everything is just mounting, and I am just one girl. You know. I tried my best, really. That’s all that you can possibly ask of me.”

“Oh.” She leaned a little on the wall, adjusting herself away from the light switch, which had dug in at first contact. “Oh, we said...”

She glanced down and noticed a large water bug on the lid of the toilet. Using the same hand that held the cigarette, she reached for a magazine—a little underground poetry publication called The Eternal Victim—and used the corner of it to push the bug off the edge of the lid. “We said a great many things. A great deal of things…we said a great many things.”

She took another drag and moved some hair away from her forehead with the palm of her hand. “And I really am sorry for doing this over the telephone. You must understand that it’s absolutely necessary, as I am just too fragile—too weak?—too fragile to do this in person right now. But it kills me in the worst way. Don’t cry now. You are the most wonderful boy. I wish I didn’t just need to be alone. I just do. But I really have no doubt that we can be amazing friends. I feel as if I may cry myself. Or pass out. I feel like I’m gonna cry. I can barely breathe.”

She got down off the counter then and stabbed her burning cigarette end out in the sink. She walked over to where the telephone was and flipped open her red address book. She picked the phone up and, cradling it between her ear and shoulder, dialed methodically. She stood very still for a moment before her hand shot up to the receiver and her head lifted straight.

“Professor Paulson, okay, Bill, good morning, good afternoon… I will take you up on that dinner, you scoundrel, you hound.”

morning Mr. Mansfield.”

That’s the way she always said it, with a chipper emphasis on the first syllables in “morning” and “Mansfield.” Her precision un nerved him. It led to everything else.

He pressed the phone against his ear. She called him at eight a.m. on the third Saturday in May for each of the last three years. Since he wasn’t at work, he could have put her on speaker, but he didn’t. What she was going to say wasn’t meant for the open air.

“So. How has the last year transpired for you, Mr. Mansfield?”

She always led off with that question, and he never answered. She already knew.

“Quite the watershed year, wasn’t it?” she added. “From man ager in the compliance division to vice president. How many vice pres idents are there again?”

He’d gone from the kitchen to the living room and sat down on the middle of his couch. He stared at the TV screen. The TV was off.

“There are sixteen of them,” she said. “Sixteen men. What do they all do, Mr. Mansfield?”

He remained silent.

“What do they all do, Mr. Mansfield?”

“I don’t know,” he said.

“You don’t know?”

“I don’t know about all of them,” he said.

“Of course you don’t,” she said. “You only know about the senior vice presidents, is that correct?”

He waited a beat, but knew he had to answer.

“Yes.”

“Why is that, Mr. Mansfield?”

“Why?”

“Yes. Why do you only know about the senior VPs?”

There was a certain relief in knowing that he couldn’t lie.

“I need to know about them because they’re the next step.”

“The next step,” she said. “That’s very good, Mr. Mansfield. I admire someone with a plan. What’s the corporate jargon for that?”

He rubbed his eyes and switched the phone from his right ear to his left.

“A very forward strategy,” she prompted. “Isn’t that right?” “Yes.”

“We all need to move forward, don’t we?”

“Forward,” he said.

“I’m delighted we agree,” she chirped. “That’s synergistic. More corporate jargon. We’ve got synergy when it comes to forward movement, don’t we Mr. Mansfield?”

“Yes,” he said. “Synergy.”

He heard a clicking sound. She was using a keyboard.

“I see that your advancement has accorded you the customary laurels.”

“Laurels?”

“Your salary, Mr. Mansfield. Emolument. Remuneration. I see you’ve done quite well.”

“Yes. Quite well.”

More tapping on the keyboard.

“Let’s talk about incentives, Mr. Mansfield.”

It never took her long to get to the incentives. It’s where they had him.

“I see you’ve still retained all the top mutuals,” she said. “Fidelity Japan Small Company, AQR Long Short Equity, Voya Securitized DAF Japanese. These all sound right to you, Mr. Mansfield?”

“Yes.”

“And, of course, with your advancement they’ve added a few more to the list, correct?”

“Added. Yes.”

“Why don’t you name them for me, Mr. Mansfield.”

“You have them,” he said. “On your list.”

There was a pause. He couldn’t hear her breathing.

“Name them for me, Mr. Mansfield.”

On command, he listed, “DoubleLine Shiller Enhanced, Colorado Bond Shares, T-Rowe Price Japan.”.

“You see? Crouching right there on the tip of your tongue,” she goaded. “And when do you vest, Mr. Mansfield?”

He fought the urge to swipe off the call. He didn’t. She’d just call back.

“And when do you vest, Mr. Mansfield?”

“Partial vestment in six years, full vestment in ten.”

“Ten years. Another decade. Sounds so long, doesn’t it, Mr. Mansfield?”

“Yes. Long.”

“Incentive. Did you ever consider it?”

“Consider what?”

motivates or encourages one to do something. An inducement. A motivation. Do these sound right to you?”

“Yes,” he said. “They sound right.”

“So what have you been encouraged to do, Mr. Mansfield? What motivation have you been induced to follow?”

His left ear started to ring. He switched the phone back to his right.

“You ask me the same question. Every year.”

“And you never answer,” she said. “Do you know why you don’t answer?”

He reached up to rub his chin. He didn’t shave on weekends, so there was a scratching sound from his stubble. He wondered if she heard it.

“Do you know why you don’t answer it?” she asked again.

“Yes.”

“Right. We both know why you don’t answer. But look at the bright side, Mr. Mansfield.”

“Bright side?”

“Waiting ten years for fruition isn’t so long, at least not if you adopt an appropriate perspective,” she said.

He waited. There was always some kind of peroration before they got down to the real business. This year’s peroration was on perspectives. Appropriate perspectives.

“Have you ever heard of melocanna baccifera?” she asked.

“Mellow what?”

“Melocanna baccifera. It’s a kind of bamboo, from India. It flowers every forty-eight years or so. Makes your ten-year vestment look like an afternoon nap, no? It also produces some kind of seedfilled fruit that attracts rats.”

“Rats,” he said.

“Black rats,” she said. “There’s a deeper meaning in there somewhere, particularly when considering your circumstances. But let’s move on to another example. Have you ever heard of the tahina spectabilis? It’s also known as the Madagascar palm. Guess how long that one takes to produce?”

“I don’t know.”

“Why don’t you hazard a guess, Mr. Mansfield?”

“Fifty years?”

“Not quite. One hundred years. Grows to an impressive size, then dies after fruiting. One hundred years, Mr. Mansfield. Considerably longer than your DoubleLine Shiller Enhanced and

There was another pause.

“Nothing to say, Mr. Mansfield?”

“No.”

“That brief seminar on the horticultural sciences was meant to encourage you,” she said. “The DoubleLine Shiller and the tahina spectabilis take time to fully produce. When they do, the reward is worth the wait... Or is it the wait is worth the reward?”

He remembered back to the first year that she called. He’d made a few remarks then, some attempts at repartee. That was before he realized what was happening. Repartee was extinct.

“Either,” he said.

“Very diplomatic of you,” she said. “But enough on perspectives and synergy. We need to review your case history.”

“Is this—”

He stopped himself there. It was a mistake.

“Is this what, Mr. Mansfield?”

He didn’t answer.

“Is it necessary? Is that what you were going to ask?”

He remained silent.

“Is it necessary, Mr. Mansfield, for me to explain to you why case history review is necessary?”

He looked up at the dark TV screen, and thought of turning it on with the mute button pressed. He picked up the remote from the coffee table with his free hand and aimed it, but didn’t click on “Power.” He put the remote back down.

“No,” he said. “It’s not necessary.”

“And, thus, synergy is restored,” she said. He heard more clicking from her keyboard. “The first case involved who, Mr. Mansfield?”

“John,” he said.

“Right. John. On the sixth floor. Quality Control. But everyone had a nickname for him, didn’t they?”

“Yes.”

She waited. He didn’t say anything more.

“And what was his nickname, Mr. Mansfield?”

“Deacon,” he said. “Deacon John.”

“Very good. And why did they call him Deacon John?”

“Because of the prayer sessions,” he said.

“That’s such a good name for them, Mr. Mansfield. Prayer sessions. Why did your cohort refer to them as prayer sessions?”

“Because of the supplicants,” he said. “They were down on

their knees.”

“Supplicants. Prayer sessions. All these delicate names. I suppose that makes it easier.”

“Easier,” he murmured.

“And who were these ‘supplicants’?”

“I can’t remember.”

“What was that, Mr. Mansfield?”

“I can’t quite...remember them all.”

“You can remember DoubleLine Shiller and T Rowe Price Japan, but you can’t recall Kathy, Lauren, Elizabeth or Kelli. Isn’t that so?”

Kathy, Lauren, Elizabeth, Kelli. As she named each one, their faces flashed before him. None were smiling.

“You called them supplicants?”

“Yes.”

“What were they praying for, Mr. Mansfield?”

Kathy, Lauren, Elizabeth, Kelli. And Deacon John. He was always smiling.

“And what were they praying for, Mr. Mansfield?”

“A chance,” he said.

“A chance?”

“A second chance.”

“Were they given a first chance?”

“What?”

“Were they really given a first chance, Mr. Mansfield?”

“I don’t understand.”

“Of course you do,” she insisted. “What was Deacon John fond of saying?”

“Saying?”

“Yes, Mr. Mansfield. His little dictum. He became quite loquacious after his third burnt martini at all those impromptu cocktail parties you boys had. What did he say?”

“His flock...”

“What about his flock?”

“He said that members of his flock must earn their benediction.”

“Benedictions. Prayers. Was it funny, Mr. Mansfield? Did Deacon John and all his euphemisms amuse you?”

“Benedictions,” he said. It was more to himself than to her.

That was the first case. Each case required an adjudication. She reviewed the adjudications as thoroughly as everything else.

“And how did you earn your benediction, Mr. Mansfield?”

His hand moved reflexively to his lower left jaw.

“That’s right,” she said. “Benediction through adjudication. And you don’t like talking about your adjudications. I’ll do it for you. We adjudicated the left second mandibular.”

He didn’t answer, but started rubbing his jaw.

“Does that ring a bell, Mr. Mansfield? The left second mandibular molar?”

He’d spent the hours immediately after the first adjudication looking for an oral surgeon. He had a regular dentist, but given the circumstances he needed to go elsewhere. He wanted someone young and drowning in dental school debt. This would ensure quick access and few questions. Dr. Nicolaides fit the bill. He agreed to take him on short notice, but Mansfield had miscalculated about the questions. Dr. Nicolaides had plenty.

“How did this happen?”

“I pulled it.”

“You pulled it?”

“Yes. It was loose.”

“Loose? How?”

“Loose. As in loose. So I pulled it.”

“With what?”

“Pliers.”

“You pulled it. With pliers.”

“Yes.”

“Why didn’t you see a dentist?”

“What would a dentist do?”

“I would have to examine it for a definitive answer. But there are options. Perhaps a tooth splint.”

“And...pulling. That’s an option, right?”

“Extraction is an option, yes.”

“Well, there you go.”

Mansfield smiled at him. He didn’t know what else to do.

“Can you tell me how?” Dr. Nicolaides asked.

“How what?”

“How it became loose?”

“I don’t know. Why?”

“Teeth usually become loose through an accident, or neglect. Your dental health seems quite sound. I can tell you’ve had regular exams.”

“Yes. Regular. And I didn’t have an accident, so I suppose it’s a mystery.”

“A mystery,” Dr. Nicolaides uttered. “Okay... May I ask who your regular dentist is?”

“No.”

“Excuse me?”

“No. I’d prefer that to remain a mystery, as well.”

The men looked at one another in a stand-off of silence.

“So,” Mansfield finally said, “what do we do?”

“Do?”

“Yes. Do. To fix it.”

They agreed upon an IDI, or an immediate dental implant, topped with a crown to restore the tooth. Dr. Nicolaides called it immediate loading. Everything has a name.

“And you recovered quite nicely, correct?” she asked.

“Recovered?”

“Your procedure to correct the adjudication. It was a success?”

He put his index finger into his mouth and ran it over the crown. It was firm, but didn’t feel like it was a part of him. It felt dead.

“We should move on, Mr. Mansfield,” she said. “We’re on a tight schedule.”

Mansfield looked at his watch. It was eight-thirty. The three

knocks would come soon. Three knocks at his door, delicate and evenly spaced.

“The second case,” she said.

She stopped there and waited. He didn’t answer.

“And the second case involved?” she demanded.

“Dancing Bob,” he said.

“Yes. Dancing Bob,” she said. “Vice president of Client Strategies. Very proficient in recruiting quality interns, isn’t that right?”

“Proficient.”

“All bright and young and female and what else? Eager. Eager to please, isn’t that right, Mr. Mansfield?”

“Yes,” he said. “Eager.”

“So eager that after Dancing Bob befriended them, mentored them and counseled them, he’d dangle a plum assignment, the plum assignment.”

“Plum.”

“Helping him with the year-end presentation on what? Yes, that’s right, the ‘forward strategy’ for the coming year. And what did this assignment entail, Mr. Mansfield?”

“Entail?”

“Yes. Entail. As in: an inevitable part of consequence.”

Mansfield didn’t answer.

“It entailed, Mr. Mansfield, a change in environment from an office setting to his home. Isn’t that right?”

“His home. Yes.”

“And that’s where he chose to take the mentoring relationship to an entirely different level. An intimate level—”

“—intimate? ”

“—by stripping down and inviting his guest to watch him shower. Is that correct, Mr. Mansfield? Just stripped right down, popped into the shower and started bobbing and dancing. Thus, his name.”

“Dancing Bob.”

“Can you imagine the sight of some flabby fifty-two-year-old prancing about in the shower?”

He didn’t speak.

“How appropriate. Silence. You know all about silence.”

“Dancing Bob,” he said again. He remembered a time when it was funny.

“And do you remember the names of his captive audience?”

Traci, Kelsey, Alex, Kristen and Julie. He didn’t say the names

aloud.

Good Morning, Mr. Mansfield - Steve Fromm

“And what was the adjudication for this case?”

Mansfield looked down at his left foot. He was wearing moccasin-style slippers. He never wore slippers before the second adjudication.

“The digitus minimus,” she said. “An excision of the three phalangeals: proximal, intermediate and distant.”

Mansfield clenched the remaining toes on his left foot. Sometimes it felt like it was still there. Today it didn’t. Digitus ipsum minimus. They came in after their three knocks at the door and did their work quietly and efficiently, installing a temporary bandage and leaving him to his own devices. He wrapped a towel around the seeping mess and found a cab to take him to the ER.

Given the nature of his wound and the high quality of his health insurance, the intake nurse expedited him in a wheelchair to the nearest examination room. He was met by Dr. Rolby and Nurse Twill. Rolby and Twill. They sounded like a 1970s folk-rock duo. After unwrapping the sodden towel and bandage, Dr. Rolby had as many questions as Dr. Nicolaides.

“What happened?”

“I was hit.”

“By what?”

“A cyclist.”

“A what?” Nurse Twill asked.

“You’re saying a cyclist ran over your small toe, and cut it off this cleanly?” Dr. Rolby inquired, examining the wound.

“No. He ran over it weeks ago.”

“Weeks ago,” Nurse Twill said. It wasn’t a question.

“Yes. I thought it was broken. I splinted it to the neighboring toe. Isn’t that the way to do it?”

“It depends,” Dr. Rolby said. “It may have needed to be put back in place.”

“Or, if it was multiple fracture, it may have required surgery,” Nurse Twill noted.

“Well, I just thought it was a simple break,” Mansfield said. “So I splinted it.”

“That was how long ago?”

“Like I said. Weeks.”

“Then what?” Nurse Twill asked.

“It started oozing and smelling.”

“Oozing and smelling,” Dr. Rolby repeated.

“Then there was the color,” Mansfield said. “Red to brown to black.” He’d done some quick Googling on the subject of traumatic toe injury before coming in.

“So then you just—” Dr. Rolby stopped there.

“—cut it off,” Mansfield finished.

“With what?” Nurse Twill asked.

“Poultry shears,” he announced.

“You cut off your small toe with poultry shears?” Dr. Rolby asked, wanting to make sure he’d heard correctly.

“Yes.”

Nurse Twill and Dr. Rolby exchanged a look that wasn’t incredulity, but fatigued amusement. Mansfield was just one more addled casualty funneled into their ER, the byproduct of a careening and inscrutable world.

Dr. Rolby took another look at the stub.

“Well, I must admit, it’s a clean cut,” Dr. Rolby noted as he felt Mansfield’s remaining toes, his foot and his calf. And it appears you did it in time.”

“In time?”

“Your skin tone and circulation seem normal,” Dr. Rolby assured.

“That means there’s probably no infection,” Nurse Twill added.

“How fortunate,” Mansfield remarked.

“Fortunate?” Dr. Rolby asked.

Nurse Twill and he traded another one of those looks before Dr. Rolby got down to business, cleaning the wound and putting in sutures. Twill took a blood sample for any possible infection that a physical exam might have missed. Rolby then sent him off with a prescription for antibiotics and some referrals for physical therapy.

“So how is your balance, Mr. Mansfield?” she queried.

He took another look at his foot.

“My balance...”

“Have you regained it?”

“Yes.”

“Good to know,” she said. “One should lead a balanced life, don’t you think?”

“Balanced, sure,” he agreed.

“How convenient that we’ve hit on that subject,” she said. “Balance. Equipoise. Symmetry. Fairness.”

“Equipoise,” he said. Such a strange word.

“It’s time to review this year’s case, Mr. Mansfield. You do know this year’s case, don’t you?”

Abigail Benning. He saw her face.

“Tell me about this year’s case, Mr. Mansfield.”

“Abigail,” he said.

“I believe she has a last name.”

“Benning. Abigail Benning.”

“Cornell sophomore. Bright. Enthusiastic. She was given an internship and started her rotation with you, is that correct?”

“With me.”

“You liked her, didn’t you, Mr. Mansfield?”

“Yes.”

“But in the right way,” she said. “Quite a rarity at your place of employment, no?”

“Rarity.”

“It was a very productive and informative six weeks,” she asserted. “But all good things must come to an end. She was sent off to the Promotions Division.”

“Promotions.”

“And who was her mentor in promotions?”

He didn’t respond.

“Shaun. Is that correct?”

“Shaun.”

“And what was Shaun’s nickname?”

He looked down at his foot.

“And what was his nickname, Mr. Mansfield?”

Equipoise. Adjudication.

“We don’t have much time,” she said. “You know they’re coming.”

He looked at his door. Three knocks.

“What was Shaun’s nickname?” she asked again.

“Shiatsu,” he said. “Shiatsu Shaun.”

“Shiatsu Shaun,” she said. “Very clever. And how did he earn that nickname, Mr. Mansfield?”

He wasn’t going to say. She knew that.

“Shiatsu Shaun borrowed a page from Dancing Bob’s playbook, and asked her to help out with a special project at his home,” she said. “A very special project. When she got there, he gave her the customary tour, which ended where, Mr. Mansfield?”

He slid his foot out of the slipper and looked at his toes. His remaining toes.

“Which ended where?”

“The massage room.”

“Very good. The massage room. Where Shaun exercised his predilection for Shiatsu.”

Predilection. Symmetry. All these words.

“Shiatsu, as in localized pressure applied in rhythmic sequence along the body,” she said. “But we all know what pressure points Shiatsu Shaun prefers, don’t we, Mr. Mansfield?”

Predilections. Adjudications.

“And you knew, didn’t you, Mr. Mansfield? All the rumors and winks and nods. It was all so amusing, wasn’t it?”

“Amusing.”

“Did Abigail find it amusing?”

A week after her visit to Shiatsu Shaun’s home, he ran into Abigail in the office elevator. She didn’t raise her eyes to look at him.

Abigail Benning. Abby.

“It’s time, Mr. Mansfield. Time for the adjudication.”

He heard the clicking of her keyboard. He’d once asked about how the adjudication was chosen, about the process.

“Process?” she had asked. “As in due process? What process do you think you’re due, Mr. Mansfield?

He didn’t have an answer, and never asked the question again.

“You’re right-handed, isn’t that so?” she asked.

His right hand reflexively mashed the phone closer into his ear.

“You’re in good company, Mr. Mansfield. Ninety percent of the population is right-handed. But does ninety percent of the population know what digitus auricularis means?”

He took the phone from his ear, pressed the button for the speaker and placed it on the coffee table. He couldn’t hold it anymore.

“Digitus auriculus,” she said again, “controlled by the fourth lumbrical, as well as the extensor digiti minimi, among others. Nine muscles in all. It really is quite a miracle, isn’t it, Mr. Mansfield? The intricacy of the design, the precise neural coordination of muscle to nerve.”

“Muscle to nerve.”

“Wouldn’t it be grand if the world were ordered so clearly, so efficiently? Connection and coordination. Intent and restult. Action and consequence.”

“Consequence,” he affirmed.

“Consequence,” she repeated. “Digitus auricularis.”

There was a stillness. He knew she was gone. He swiped off the call and put the phone back on the coffee table.

“Digitus auricularis.” He pronounced it aloud, then raised his right hand and looked at his small finger. He heard the sound of a ticking clock, though he had no clocks that ticked. It was something he heard when waiting. Waiting for the three knocks.

Mansfield got up from the couch, quietly walked to the door and looked out the peephole. There was no movement. He opened it and popped briefly into the hall. Nothing. He stepped back in and locked up again.

It was just him, all alone. All alone with the ticking and the waiting. That’s when he decided to get out. Anywhere. Anywhere but here. The protocol was to wait for them to arrive and execute the adjudication. Avoiding the adjudication would bring consequences. He had no idea what the consequences would be. He didn’t care. Digitus auricularis. He knew that much.

Mansfield dressed quickly, grabbing his wallet and keys on the way out. He left his phone on the coffee table. He didn’t want to hear from anyone. As he walked down the hallway toward the elevator, he heard it ping. It was stopping on his floor. He made a beeline for the stairwell exit. Just as he arrived at the egress, he heard the elevator doors opening. He rushed down the two flights of stairs to the lobby

and into the street.

He knew where he was going: Blue McAuliffe’s, an upscale whiskey bar two blocks away. Blue Mac’s had a staff of taciturn bartenders who took pride in treating customers with a silent contempt. It was an attribute that ensured Mansfield’s steady patronage. He walked the two blocks rapidly, keeping his eyes down, sensing more than seeing people as they passed him on the sidewalk.

Blue Mac’s was opening right when he arrived. The bartender, a woman he hadn’t seen before, was cleaning glasses. Mansfield sat on the stool farthest from the door. The bartender sidled up to him. He didn’t make eye contact as he ordered a Balvenie 12. He placed his hands on the bartop, staring at them as she returned with his drink and wordlessly set it in front of him.

Mansfield didn’t pick up the glass, but stared down into it, into its near-amber richness. Clear and clean and simple. He glanced at his right hand. Digitus auricularis. He stuck his small finger into the scotch and gave it a stir. He was about to lift the glass to his lips when he heard the front door swing open. He didn’t look up. From the shadowy edge of his peripheral vision, he saw two shapes sitting at the bar, three stools away from his own.

He waited a few moments, then slowly pushed the glass away from himself. He got up and headed toward the men’s room. It was empty. Mansfield went to the end stall and latched it closed. He stood still, waiting. The main door to the bathroom creaked open. Footsteps followed. He held his breath. Three knocks. Light and steady. He didn’t move. There wouldn’t be three more. They were patient. They’d wait forever.

My Goliath is internal

And thus stronger than the Ancient brute

And I feel That the stone I swing Is but a kernel

That will hardly do damage

To this human beast Ferocious and hirsute

A wash of birds

Flocked across the sky

The sun persisted

I forgot to cry

And watched my prayer disappear in the distance

A little crate of figs Happy and translucent Rain falling on my lips

My lips on the right side have an open space like a squiggly line drawn by my four-year-old self. “Close your mouth,” my mama said, “Your upper lip will curl.” My lifelong struggle to keep my mouth shut, stretching the upper lip over my horse front teeth, like a t-shirt that rides up.

All those words, all those words not spoken back. Only the slow seep of air through the crack in my lips, whispering… No, I can’t say it, No, I’m not sure I should, No, I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I’m so sorry.

The tsunami that’s at the cusp of the deep dark crack in my lips just broke free…free, free, free, opening my mouth in the widest yawn to sing No, hallelujah. No, hallelujah. Hallelujah…yes, yes, yes.

Not for its victims, for whom timing was everything—too late for them.

Not for the millions slaughtered in the camps—was Nuremberg a triumph?

The tens of millions un-personed by Stalin, Pol Pot, etc.

What benefit to them the death of the dialectic? Reconciliation committees?

Nor for the murdered Bosnians, machete-hacked Tutsis, beheaded Af ghan women

How have the ex post facto treaties helped them? Pieces of paper signed by politicians.

Chemical weapons still tolerated. School shootings becoming a na tional pastime.

No coincidence, since evil is much faster than good, violence leaving peace in its dust

Evil explodes into the world, an independent force, immune from reason

It shocks, horrifies and stupefies comprehension, strategy, response, paralyzing action

Accelerating, gaining momentum exponentially, expanding, succeeding, gloating, destroying Completely and permanently—people, places, history, memory, men tal health

While the good ask “how,” “why,” “what” to do in a de rigueur and futile exercise in dialogue

For years before evil is stopped, implodes on its own, mutually exclu sive, irrelevant from good

Leaving soul-crushing grief, loss, damage that permeates, persists in the psyches of survivors

As the untouched, the unaffected, the never-in-danger celebrate the alleged victory of the good.

Not necessarily out of ignorance, or malice, or even callousness toward the suffering of others

But because evil can never be eliminated, not even fully prevented, only reacted to

As best we can, with our limitations, with the inherent limitation and obliviousness of goodness

Which by its very nature first seeks only to see itself in others, in everything, until proven wrong

A slow process that gives evil a head start while trust is passively placed in good to triumph

Slowed further by the relentlessness of existence, the immediacy of personal consciousness

Too narcissistic, too demanding, too arrogant to just cease, drop everything and change focus

From the particular to the universal, from itself to others, especially those distant and foreign

In time to do anything other than reflect on the continuing and undeniable effectiveness of evil

On the days when my only friend came to visit her mom her mom would clean herself up they’d sit tight knotted table in between and chain smoke

Later after her mother left the table to shoot up my friend would ring my bell we’d head to the train trestle and sit with legs dangled over the bridge smoke all the cigs she clipped from her mom we threw rocks at the top of the freight train as it whipped by scream mother fucker no one to see hear us or care

When we returned we would find her mother curled up in the corner drool running down her chin

My friend would be on the juice by eighteen and prostituting from the same two rooms her mother crawled through half dead to be carted out—half a veg sent to another rehab

When we kissed atop that weed-filled bridge the train speeding so fast under our worn sneakers we didn’t realize the electricity that ran through us charged our limbs melded us together as heavyweights we just didn’t see it coming straight for us

The one about Brenda turning the leaf and the other about Brenda dying which came first Brenda’s death or Brenda’s turn?

I want to write a happy ending I want to leave out her emaciation the fixes the vomit-strewn trailer

Brenda my girl had I not walked in to get my own fix had I not seen you gray and foaming and without any smarts— cuz you know I was never very bright I ran out screaming Jesus to the pay phone to hit 911 and scream into the phone come quick she ain’t breathin

I want to write something epic but I fumble all I got is shit

Brenda my girl this is for you this is for the boardwalk at Rockaway underneath with our blanket our needles our prayers to our made-up water god we pretended

would save us from the waves the incredible smile on your face when I found that $20 bill

The second poem just can’t birth unless it oozes out stillborn cuz the second poem haunts the first yet I keep writing as if I have something to say if I listen so long to something completely unbelievable I will come to swear by it Brenda I will

I. 1986 the Buick Regency light blue with a dark blue top, velvet seats so plush baby it was a boat of a car drove itself down Cross Bay Boulevard to Rockaway Beach 117 too much to drink too much to snort pulled over to vomit a blue wave of Giffard Curaçao the color of our interior smoked a cig recovered

II. Headed south to the beach to sit under a silver moon slid over to me on the passenger side tried to love me you were inoperative defunct dead heard the waves crash over and over as the moon magnetized the ocean and we stared like it was our end as if this were the last high the last non-working play

III. The Buick our amphitheater listened to the song “When Doves Cry” over and over dawn beckoned limpness cradled you mumbled it’s ok I already knew you shot up listened to the waves one more time with nothing left but that damn hooptie your cleft chin—devil within as I always joked even before the Buick before dawn before sexless desires of powder and pills

IV. Was so good to see the sun rage up its rays blinded us to fainting stumbled out to the mecca you vomited again I ran my hand over the sand thought this was so simple never asked you for anything yet it was a life sentence and I just your sidekick along for a death ride

Yuan Changming

In English, family is a word to say: Father And Mother I Love You

Whereas in Chinese, 家 is

A pictograph offering

A shelter 宀

To or a big pig 豕

1/

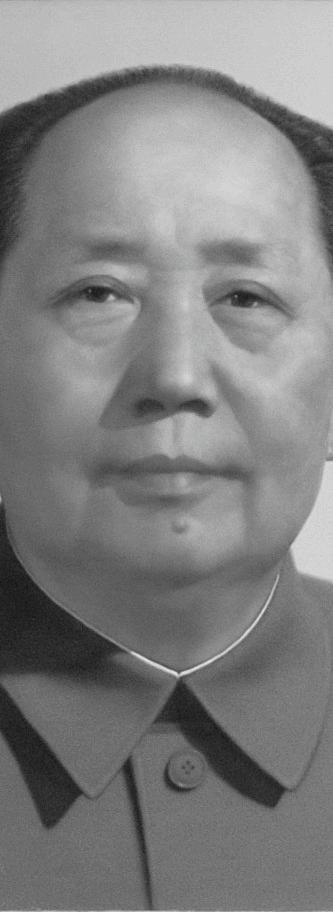

Is it a linguistic coincidence or undeclared prophesy? But sixty years after Mao Zedong approved The scheme for simplifying Chinese characters We are now living in an open & reformed age, where

愛/ai/ [love] has become a feeling without a heart: 爱 親/qin/ [kinship] someone who is not to be seen: 亲 兒/er/[son] a person without his own brain: 儿

郷/xiang/ [village] a place where there’s no male: 乡

厰/chang/ [factory] a building with nothing inside: 厂

産/chan/ [manufacture] a process without production: 产

雲/yun/ [cloud] a nimbus offering no rainfall: 云

開/kai/ [open] an action to break something doorless: 开 導/dao/ [lead] a guidance without the Way: 导

More than half a century long after The simplification of classic Chinese characters & almost half a century well after China opened its doors & began its reforms To shake off its deformities or backwardnesses:

魔 /mo/ remains the same as 魔 [evil], so does 鬼 /gui/ as 鬼 [ghost], so does 偷 /tou/ as 偷 [steal], so does 黑 /hei/ as 黑 [darkness], so does 贪 /tan/ as 贪 [greed], so does 赌 /du/ as 赌 [gamble], so does 毒 /du/ as 毒 [poison], so does

贼 /zhei/ as 贼 [thief], so does 骗 /pian/ exactly as 骗 [cheat], which remains As unchangeable as Chinese per se, or does it not?

Each time I step out Of my door, I wish to Relocate my neighbor’s Garden into my own Backyard, or simply Sabotage it to deflate My deeply rooted envy

Yesterday, at twilight I proposed to switch Our houses like some others

Doing their wives Or husbands

Just for a night

For a change

For fun

For a feel of Ownership of The grass that Is always Greener on The other side Of my fence

When I die

I want to be stuffed stuffed and mounted on the wall like some poor old deer who got caught in the headlights

Not just the antlers mind you but the whole fucking catastrophe― glass eyes mop of hair scars stretching beyond Wyoming Gutted by the skin of my teeth like dead animals and birds I want to be filled with that special fake something― that makes me look like I’m alive― the stuff that dreams are made of

When I die I want to hang around collect dust remind everyone that even if I am well past my expiration date I’m still here Well perhaps not in any meaningful way but a testament to my long shelf-life (perhaps a little shelfish of me) Alas… How strange to be so prominently displayed in my own absence… able now to appreciate the trophy I really was in anticipation

Keeping alive the art of keeping the dead alive takes talent― one I don’t have as of yet and a souvenir that won’t keep until only after I’m gone Life’s funny that way

Behold the temple!

The temple of which the king was proud And who adored it as he did all of his children Children, whom in the futile gest to repay his debt to his duty, Would sooner forgive him their own funerals And likewise forbid mourners, As they exchange their armor for the honor Of golden robes perfumed in black incense

Peace was the wish, but in this garden were wicked weeds

And as time passed the vigilance of the gardeners waned

And yet Priam never saw his trust betrayed But soon enough he was under siege

And the tempest of the sons of Troy Would mean many a rough passage for the boatman

None of them had to be told Without fear they carried coins for the crossing So was their father and his temple worth their eternity, And yet mixed with his sweat were tacit tears Made so by the hand he wished he could lay one last time

Upon the shoulder of each soldier Every one of them named “Paris” or “Hector”

The palace being meaningless, he designated the citadel