19 minute read

Watching wildlife

from the kayak seat

Advertisement

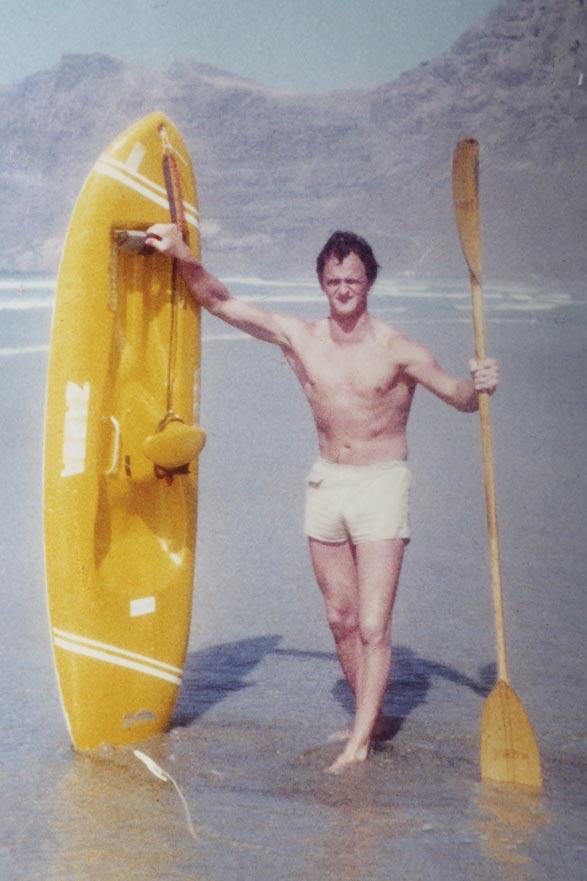

Words and photos: Rupert Kirkwood For the last fifteen years, I have paddled around Devon and Cornwall’s coast, observing and photographing its fantastic wildlife.

Occasionally further afield: the west coast of Scotland and the Outer Isles, France, Spain, Greenland, USA, Mexico, Chile and Antarctica. These places are great for kayaking and have provided some exceptional wildlife moments, but I have always been a great fan of my home patch, and what you can see by just churning out the miles. So my most memorable and fulfilling paddling adventures have been right here in southwest England. I have always had a passion for natural history, and kayaks have always been my main sporting and recreational interest. First messing about on the River Thames, then a short spell of marathon racing, and a couple of decades of waveski surfing in north Cornwall whenever I had some time off from a busy schedule as a farm vet in west Devon.

Sit-on-top (SOT) kayaks appeared on the scene at precisely the right time. I was starting to get fed up with how crowded the waves were becoming with surfers, so was contemplating a change to coastal touring. But I hesitated to purchase a sit-in sea kayak because of the worry of tipping over. I had been shaken by a nasty incident where I was trapped upside down in boiling surf on my waveski, unable to find the quick release on a seatbelt which had become twisted. As a result, I eventually managed to roll up, ditched wearing a seatbelt and became a convert to the SOT principle. Easy self-rescue, safety, simplicity and freedom of movement.

So I bought one of

of the first Ocean Kayak Malibu 2s to arrive in the UK. Nothing much more than a flat boat-shaped piece of plastic, but fantastic for short worry-free coastal trips, surfing, fishing, and real family fun. I progressed onto a series of single SOTs: Ocean Kayak Prowler 15, Ocean Kayak Scupper Pro, Wilderness Tarpon 160. I was always looking for that compromise of comfort, speed, load-carrying for camping, and suitability for fishing. I became a very enthusiastic kayak fisherman. Trolling a lure whilst paddling along quietly just made an enjoyable pastime even more exciting. Whilst piecing together the whole of the southwest coast, I caught over 25 species of fish. I also clocked up a lot of miles, 1,155 to be precise, between Poole and Minehead. This includes paddling up every creek as far as I could go at high tide, and out to all the islands. It’s 630 miles if you walk the coast. I was delighted to complete the three ‘big’ open sea crossings in southwest England, in recreational SOT kayaks. Eddystone and Lundy there-and-back, and Scilly (featuring Leatherback Turtle!) one way, were all about 30 miles. What SOT kayaks lacked in speed, they made up for in comfort. The first sensational monsters I came across were a couple of Basking Sharks at Land’s End. I just sat gaping in amazement at their colossal size, with the top of their fins level with my eyeballs

CATCHING FISH FOR FUN

My kayak-fishing era came to an end when the threats facing all creatures that lived in the sea were starting to become evident. Catching fish for fun (because I am not particularly fond of eating fish) didn’t sit comfortably with my lifelong appreciation and respect for nature, even though the vast majority were released unharmed.

So I swapped my fishing rod for a camera. And if somebody had given me a list of all the incredible animals I was going to see in the dozen or so years since then, I would have rolled my eyes in disbelief.

My fascination for marine megafauna was sparked by an encounter with Fungie the Dingle Dolphin, from my waveski, 30 years ago. Still, I didn’t get going with dolphins and their fellow-creatures again until recently. The first sensational monsters I came across were a couple of Basking Sharks at Land’s End. I just sat gaping in amazement at their colossal size, with the top of their fins level with my eyeballs. Far, far longer than my kayak, and twice as wide. They kept on circling round and round with me in the centre, no doubt checking out whether I was a fellow shark. One misjudged its depth as it passed underneath my hull and momentarily heaved my kayak out of the water. I enjoyed several years of frequent basking shark encounters around Cornwall (and a few in Devon) until 2013, but since then their annual appearance in late spring seems to have more or less stopped.

CHOICE OF BOAT

I was always on the lookout for a narrower and faster SOT kayak that would make offshore paddling a bit more practical. I snapped up a second-hand, supremely cool-looking, South African-made Paddleyak Swift, a great craft and suitable for notching up the miles, but not comfortable enough to spend all day in the seat. No backrest.

Next came a Cobra Expedition, 18-foot long and 23 inches wide, a superb and narrow SOT that was roomy enough for multi-day camping expeditions, and capable of tackling some serious stuff as paddling around St.Kilda solo. (Not my most relaxing paddle ever). My current craft is an RTM Disco SOT. I have nosed past my 60th birthday and have to look after my back when lugging a kayak. The Disco is light, reasonably fast, sleek, and, now I have glued four layers of a camping mat to the seat well, very comfortable. Good enough for an all-day trip.

SHELTERED CREEK

My initial exploration in search of wildlife was close inshore and up the hundreds of miles of sheltered creek in southwest England. As a lifelong ornithologist, it was always thrilling to hear the piping of Redshank and Greenshank echoing around the wooded valleys during a winter trip or the turquoise flash of a Kingfisher. Less frequent were the sightings of foxes, deer, and once even a badger, swimming across the tidal creeks. Early-morning trips down the Tamar, Taw and Torridge were rarely without a sighting of an otter, and I have even come across the occasional, unofficial, beaver.

In 2015 I decided I wanted to see a whale from my kayak. I knew this was a bit of a crazy target, as I had only heard of whales being seen on a few occasions, by fast boats which can eat up the miles – never from a kayak. The only way I would see one was by paddling as far offshore as possible, as often as possible. Finding a whale is like looking for a (very large) needle in a (very, very large) haystack.

Offshore paddling

My offshore jaunts were and still are, always thrilling. I never know what nugget of nature will appear in front of me next. But paddling around in the open sea is not every kayaker’s idea of a great day out. It is a bit light on scenery, cream tea shops are few and far between, and there is no chance of getting out to ease that aching back. So unless you are a really serious wildlife enthusiast, and are happy to take the risk of seeing nothing at all for the entire day, stick closer to shore. However, for me, the excitement of offshore wildlife encounters from the kayak cannot be overstated. Unlike creatures on land or along the coast, animals of the open sea are not wary of insignificant humans sitting on unfeasibly flimsy craft. Quite the opposite, a kayak acts as a magnet to virtually all passing fauna, because anything that breaks up the monotony of the sea surface generally means fish. Gannets circle overhead, dolphins are inherently curious, and even Puffins were sitting on the surface paddle over to have a look. In the Antarctic, last February, an inquisitive juvenile Humpback Whale escorted by its mother swam around our posse of kayaks for ten minutes, often on its back, before surfacing a few feet away from my wife and myself in our double (sit-in!) kayak and soaking us with the spray from its blow. There is no worry about causing a disturbance when far out to sea when you are paddling along at three knots with hardly a splash. If a dolphin takes a dislike to you, one flick of its tail and it is gone. The disturbance is a developing issue along the coast, with an increasing number of kayaks and SUPs harassing seals and sometimes inshore pods of dolphins. But not in the same league as jetskis, of course.

PORPOISES AND DOLPHINS

Porpoises are the cetaceans I observe most often. Very small and very aloof and difficult to see unless it is calm. Charming little creatures nonetheless. In whaling days they were called ‘puffing pigs’ because they breathe with quite a sharp blast, that can be heard from long distance. Common Dolphins are my absolute favourite and seem to be increasing in numbers. They are splashy, dynamic, charismatic and very social. As I cautiously approach a pod, a couple of bulky ‘bouncers’ come over to check that I do not represent a threat (such as an Orca), before the rest of the gang joins in the fun. Adults were sensible, adolescents were leaping about all over the place, and calves stuck to their mother’s side like glue. Common Dolphins are by far the most numerous dolphins, and I come across them about 20 times a year, followed by Bottlenose once or twice a year, the extraordinary Rissos maybe once a year, and finally White-beaked Dolphins that I have only seen once.

FIRST WHALES

My first whales were during summer trips to Eddystone lighthouse, 12 miles beyond Plymouth breakwater. During quite a lumpy crossing, I just happened to glance around behind me as the long

back of a juvenile Minke Whale surfaced. A view of about a second, and then it was gone, and I didn’t see it again. But what the heck, it was my first whale!

A month later, I had the most sensational prolonged viewing of another Minke, this time, a full-sized adult, close to the Eddystone reef. It was such a thrill to be sitting far, far offshore, in glass calm conditions, no other human within sight, shearwaters zipping past, porpoises puffing and every so often the great blast of a surfacing whale that makes the hairs on the back of your neck stand up. In my view, the most evocative of all the sounds of the animal kingdom.

BIG DAY AT EDDYSTONE

As usual, I was bursting with excitement as I paddled out from Plymouth sound towards Eddystone in early August this year. This is the time of year when cetaceans reach their peak numbers, feeding on the seasonal boom in shoaling fish such as sandeels and mackerel.

It was the first day of light winds for weeks, and the surface was as calm as it gets. I had passed a pod of porpoises and dolphins before the sun had come up. Three miles offshore, there was an explosion of water behind me. Not the benign splash of dolphins, or the slap of a breaching sunfish, but a ripping noise that made me crank my neck around in an instant. An area of the sea the size of half a football pitch was being churned up by a load of enormous fish whose spiky fins were raking the surface. With an occasional one, the size of a dolphin, jumping clear. Giant Bluefin Tuna!

This was not the first time I had seen these fantastic fish, but I had never seen them in this sort of quantity because for the next hour hardly a minute went past without another explosion of water somewhere within earshot. I saw up to a hundred tuna appear at the surface; there must have been many thousands more underwater – who would ever believe that –and all within sight of Plymouth? The action didn’t stop there. I heard sploshing of tuna, porpoises and dolphins all the way out to the lighthouse, complemented by a couple of Sunfish and a Blue Shark at the surface. And on the way back three different Minke whales sliding through the water like enormous porpoises, accompanied by that giant puff of air.

THE DAY OF THE HUMPBACK

Unquestionably my most remarkable offshore wildlife day was in early August 2019. It becomes more unbelievable as time goes on. I still can’t believe that I happened to be in EXACTLY the right place, at EXACTLY the right time, to see one of the most dramatic sights witnessed in recent times off the Cornish coast. I had paddled out from Penzance four hours previously, and was three miles off the

e coast, just following my nose. I suddenly found myself in a frenzy of activity – I could see bait balls of sandeels swirling below my kayak as porpoises, dolphins and tuna herded them into a more convenient tight ball for a decent mouthful. Shearwaters and Gannets milled about overhead. As I enjoyed the show while browsing on a chocolatey snack, I kept thinking I could hear a prolonged blow from further towards Lands End. I was a bit reluctant to paddle further, because the big Spring tides were already dragging me down the coast at over a knot, giving me a long paddle back. However, when I saw, half a mile away, a giant grey back launched upwards and fell back with a monumental splash, I was off to investigate at top speed. It emerged again much closer, and I cautiously paddled up to where the disturbed water was still fizzing with bubbles. The whale lunged out again nearby, a school of sprats scattering as they tried to avoid being engulfed, and then everything went completely quiet. Until little fish started jumping out of the water around my kayak – Yikes, the Humpback was on the way up beneath me! Fortunately, it chose to eat a baitball a hundred yards away, not the one that was taking refuge beneath my hull. It finished off the show by waving a gigantic white pectoral fin in the air and raising its mighty flukes for the last time, with St.Michaels Mount conveniently in the background for the perfectly ( and very luckily) composed photograph.

AND THEN IT WAS GONE

This was a spectacle I will find hard to beat not least because I watched four species of cetacean (Humpback, Minke Whale, Porpoise and Common Dolphin) plus a few Giant Tuna while sitting in the same place in my kayak without paddling a stroke.

AROUND THE WORLD (SORT OF)

Over the last 15 years, I have notched up well over 25,000 miles of paddling, so more than the circumference of the earth, and have seen various animals that I had no idea lived in UK waters, let alone that you can see from a kayak. As I nudge a bit further into my sixties, my motivation to get out onto the water remains undimmed. A kayak is such a perfect platform for watching and photographing wildlife, uninterrupted

‘audio’ and causing a minimal disturbance with an unobstructed view. Maybe I will only see a few seals or hear a handful of excitable Oystercatchers, or perhaps I will see one of the stars at the top of my wish lists such as an Orca or Pilot Whale. The magic of the kayak does not fade!

SAFETY AND PLANNING

I carry a lot of safety equipment because I frequently paddle solo: two phones, VHF radio, GPS (Garmin 72H), personal locator beacon, flares. I contact the local NCI (Coastwatch) station by phone or radio as I paddle out, with my approximate return time. But the key to safety is careful planning. I make sure I know exactly what the wind, including gust forecast, is doing, using XC Weather and BBC weather forecasts.

I know precisely what the tide is doing, and the tidal coefficient (how big it is), using tides4fishing website. Also what time the tidal flows change direction, which often doesn’t coincide with high or low water, especially along the south coast and at Land’s End. Finally, I like to know how much groundswell is running, particularly important when planning trips in north Cornwall or Devon.

I never cease to be amazed at how difficult it is to predict the sea state. For example, even the slightest tide running against the lightest wind will throw up a bit of a chop, and headlands magnify all the effects of wind, current and swell, and so I treat them with the utmost respect. For me, an absolutely flat sea is the key to both enjoyment and wildlife watching. Glass calm means you can see the fins from a mile off, hear all the puffs and splashes. You can take photos in a relaxed manner from an excellent stable platform. And you can have an enjoyable lunch break with your legs dangling over the side of your kayak.

ESSENTIAL EQUIPMENT

Paddle: I use a Werner Camano straight full carbon paddle. No apologies for no expense spared! It’s your most important bit of kit. Paddling suit: In the summer I wear wetsuit trousers and a light top. For the rest of the year, I wear Reeds Chillcheater dry trousers and paddling top. Camera: I use a Panasonic Lumix FZ2000 for scenes, wildlife and videos. It’s one of the best bridge cameras and has a 24-480mm lens. In good light, it produces images as good as a DSLR and is hugely more versatile. However, it is entirely non-waterproof, so it lives in a dry bag until I see something exciting. Then I take it out, and it sits on my lap, and I hope it doesn’t get wet! For underwater stuff, I use an Akaso V50 action camera (like a GoPro). Roofrack: My Karitek ELRR roof rack that drops down low so that I only have to lift the kayak to waist height, has undoubtedly protected me from back and shoulder strain. If it prolongs my paddling career by a couple of years when I otherwise might have been stretched out on the physio’s bench, it is worth every penny!

The Blog

All my adventures, encounters, pics and videos can be found on my blog: https://thelonekayaker.wordpress.com.

FreeStyle canoeing – it’s not just all about the SONG

AND DANCE

But on the other hand…

Using music to help unleash your paddling skills Words: Bruce Kemp, with contributions from Paul Klonowski, Marc Ornstein, Bob/Elaine Mravetz Photos: Bruce Kemp, Jim Lewis, Rick Lalonde, Marc Ornstein

I first became aware of FreeStyle by seeing some performances of paddling routines that had been choreographed to music, aka Interpretive FreeStyle or ‘canoe dancing’. While I had no real interest in the performance aspect, I surely wanted to learn how to handle a canoe and those folks. After my first symposium a dozen or so years ago, I quickly discovered that the manoeuvres and techniques I was learning had a significant and positive effect on my ‘everyday paddling back home’, as we sometimes phrase it. As my FreeStyle instruction progressed, I unexpectedly discovered something else too – that paddling to music can be an effective and useful practice tool. I don’t mean creating and paddling an interpretive routine, necessarily, but rather just paddling along to the music playing in the background, just as you might have music on around home or at your workplace. I suggest that you give it a try when you’re out for a leisurely hour or so on a local lake or pond, or just generally practising your boat control somewhere, and will describe some ways that it can be helpful. It is common for newcomers to FreeStyle (myself included, back in the day) to find their Instructor reminding them frequently to slow down. Relax. Don’t paddle so hard. FreeStyle is a body of technique which emphasizes efficient paddling, in this case meaning conserving the physical energy of the paddler by making use of a selection of paddle placements, blade angles, canoe heel and pitch, in various combinations to harness and direct the boat’s own momentum such that it may be used to augment a paddler’s power. To be sure, there are certainly paddling situations when a paddler needs to pour on the gas – to duck into an eddy on a fast-moving stream, or power through a tricky spot on some churning rapids. But unless you are a hard-core whitewater paddler or a racer of course, then most of the time full-out power is not necessary, and more often than not may be counter-productive. A controlled and relaxed cadence will do just fine and is in fact, preferable for the long haul (see Marc Ornstein’s Cross Post article ‘Slow and Steady’ for more http://freestylecanoeing.com/slow-and-steady/).