4 minute read

What would the GOP plan actually do to the budget?

By MARGOT SANGER-KATZ and ALICIA PARLAPIANO

House Republicans want to cut federal spending — and they just passed a bill that would do that.

Advertisement

But they don’t want to cut defense spending. They don’t want to cut veterans’ health care spending.

They don’t want to cut Medicare or Social Security.

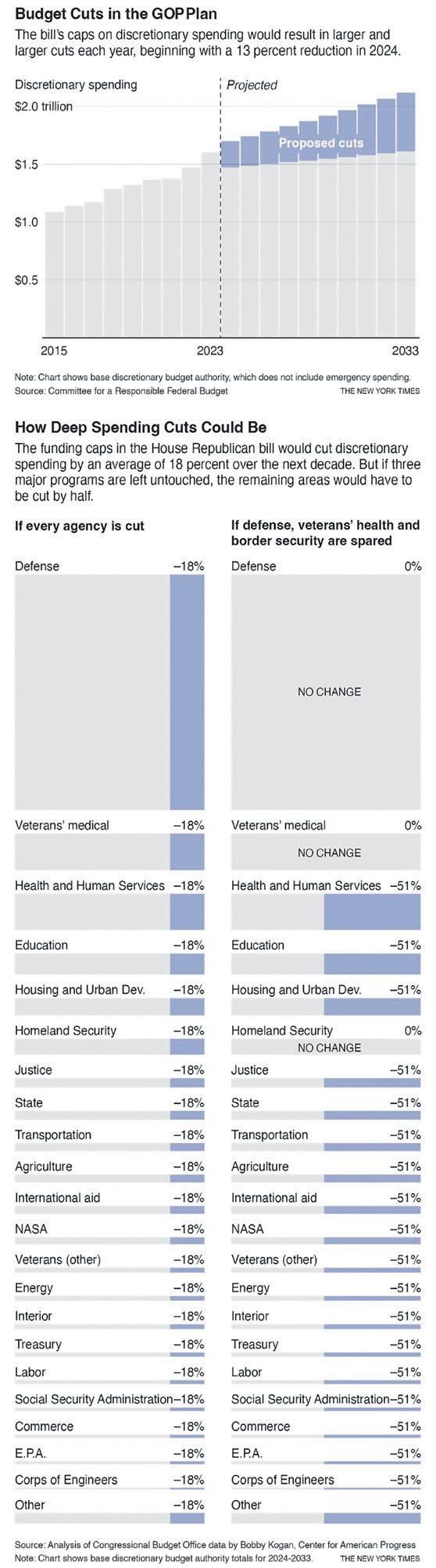

Their bill, which would raise the country’s borrowing limit for a year in exchange for a decade of spending reductions, does not include many specifics. It achieves most of its savings with spending caps for discretionary spending — the part of the budget allocated annually by Congress that is not automatic like Social Security payments — but it doesn’t say what discretionary programs should be cut and which ones should be spared.

If the entire discretionary budget were subject to cuts, the reductions would be “aggressive” but “achievable,” said Marc Goldwein, a senior policy director for the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, which backs deficit reduction.

But if favored programs are protected, the cuts everywhere else will get much deeper and harder to implement. “It goes from being an achievable goal to one that would be very difficult to achieve,” he said.

The White House has been attacking Republicans for proposing cuts to veterans’ care. Republicans in House leadership have responded that no cuts are intended. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy has promised he will protect the military from reductions, although the bill as written does not exclude them. And Kay Granger, chair of the House Appropriations Committee, has said border security remains a top priority.

The bill is McCarthy’s first big move in negotiations over the debt ceiling, which he has argued should be tied to reductions in federal spending to lower future debt, although there is no legal reason it must be. If Congress doesn’t raise the limit on how much the country can borrow to pay its existing bills by June 1, the Treasury Department may be forced to default on its bonds, an underpinning of the global economy. President Joe Biden wants Congress to raise the debt limit without conditions, saying he’s willing to talk about the budget, but not under a threat of default.

McCarthy was scheduled to meet with Biden Tuesday at the White House.

Universal discretionary caps would cut spending by an average of 18% over a decade, compared with what’s expected if current levels grew according to inflation. But with defense, veterans’ care and homeland security exempted, the caps would result in cutting the rest of the discretionary budget by more than half.

Defense is the largest category of discretionary spending in the budget. Veterans’ health care is the second largest.

The programs that would be subject to deeper cuts include nutrition assistance for poor mothers and infants, air traffic control, the State Department, cancer research and Social Security Administration employees. Those are initiatives that many Republican lawmakers and voters value.

The actual decisions about how to apply reductions would fall to lawmakers on the appropriations committees, who could parcel out the cuts in any way they can agree on.

“It’s easy to write budget caps,” said Bobby Kogan, the senior director of federal budget policy at the left-leaning Center for American Progress and a former Senate and White House budget staffer, who analyzed the bill. “It’s hard to actually legislate what to cut to live within those budget caps.”

Even some Republicans who voted for the bill last week expressed discomfort endorsing cuts to the energy credits, which are helping to fund projects in their congressional districts. An analysis released by the nonpartisan Tax Policy Center on Wednesday found that repealing the energy credits would result in modest tax hikes, particularly for high-income households.

The fight among Republicans about what to protect from the budget caps is a smaller version of the broader challenge that Republicans have faced in their efforts to lower the federal deficit. To earn his speakership, McCarthy promised lawmakers that he would propose a plan to balance the federal budget in 10 years, a goal that would require much bigger changes than those contained in the current bill. But that plan began to look implausible as McCarthy took many of the biggest government programs off the table.

If Congress is unwilling to touch Medicare, Social Security or military spending — and is unwilling to raise any taxes — balancing the budget requires enormous cuts to the rest of the government.

This package, with its more modest budgetary ambitions, appears to be a recognition of that difficult math. But with all the promised exclusions, it still would seem to require hefty cuts from popular government functions. In letters to Rosa DeLauro, the leading Democrat on the House Appropriations Committee, agency heads described the changes they would need to make in 2024 to absorb a 22% cut, one that assumes Republicans would protect military spending but apply the budget caps to veterans.

— The Federal Aviation Administration would need to close 125 air traffic control towers.— Cuts to the Women, Infants and Children nutrition program would eliminate food assistance for 1.2 million poor Americans with young children.— Pell grants would fall by $1,000, and be eliminated altogether for 80,000 students.— Two million families would lose access to medical care at community health centers.— The FBI would need to reduce its staff by 11,000 employees.— Claims processing at the Social Security Administration would slow by months.— Reductions to the Head Start program would mean slots for 200,000 fewer children.— NASA would need to halt the Artemis program sending more astronauts to the moon.

If veterans’ care and homeland security are also insulated from cuts, those programs would need to be reduced by far more than 22%.

Taken together, the package would reduce federal deficits over the decade, coming close to stabilizing the ratio between overall federal debt and the size of the economy, a long-term goal embraced by many economists.

But most of the bill’s savings come from the caps, and that means that Congress would need to actually carry them out to achieve that outcome. Given McCarthy’s many promises to his colleagues, that seems hard to imagine, even if he could somehow persuade the Democratic Senate and White House to adopt the bill.