61 minute read

Competitions

Win a Glasgow Film Festival ticket bundle!

Glasgow Film Festival returns for its 16th edition from 26 February to 8 March, and The Skinny is once again partnering on an exclusive strand of films. You have the chance to win tickets to each of those events – PLUS a pair of tickets for the sold-out Opening Gala.

Advertisement

One winner will receive a pair of tickets for opening film Proxima, as well as About Endlessness and Days of the Bagnold Summer. They'll also receive tickets for the Soundtracking event where Simon Bird and Belle and Sebastian's Stuart Murdoch will discuss ...Bagnold Summer's soundtrack with Edith Bowman, plus a pair of tickets for The End of the Festival party with Rebecca Vasmant.

Proxima

To be in with the chance of winning this fantastic prize, head to theskinny.co.uk/competitions and answer the following question:

When does Glasgow Film Festival 2020 start?

a) 6 February b) 16 February c) 26 February

Competitions closes at noon on Mon 17 Feb. One winner will receive two tickets for each of the screenings/events listed; tickets are non transferable. One entry per person. Entrants must be 18 years or older. There is no cash alternative to the prize and no other prize is available. The winner will be notified by email and will have 48 hours to respond or the prize will be offered to another entrant. The Skinny’s Ts&Cs can be found at theskinny.co.uk/about/terms

For more information on GFF 2020, visit glasgowfilm.org/glasgowfilm-festival

Journey through the vast networks of neurons in the planetarium, have a chat with mindful experts and try out brain-altering exhibits and refreshments. We have tickets for you and three friends to enjoy Science Lates: Inside Your Mind at Glasgow Science Centre on 20 March to be won – and the prize includes a sharing flask of cocktails and a party-size portion of chocolate-dipped doughnuts to share with your friends. What is a neuron?

a) A nerve cell b) A stem cell c) A blood cell

Competition closes midnight Sun 1 Mar. Entrants must be 18 or over. Winners will be notified by email and will have 48 hours to respond or the prize will be offered to another entrant. The prize consists of four tickets for Science Lates: Inside Your Mind on Fri 20 Mar. The Skinny’s Ts&Cs can be found at theskinny.co.uk/about/terms

Find out more about Science Lates, and book tickets, at glasgowsciencecentre.org/science-lates

Science Lates

DOWN 1. Business Time 2. Baking 3. Odessa 4. Tend 5. Rough Rider 6. Minotaur 10. God Only Knows 12. Landscaped 13. Tease 16. Wild Bill 20. Albino 21. Orchid 23. Skin

ACROSS 1. Baby Dont Hurt Me 7. Eon 8. Idioms 9. Ding-Dong 11. Eggplant 14. Arya 15. Uno 16. Winona Ryder 17. TMI 18. Lust 19. Eharmony 22. Embraces 24. Beacon 25. KPI 26. Slide Into My Dms

Crossword Soultions

Passion Projects

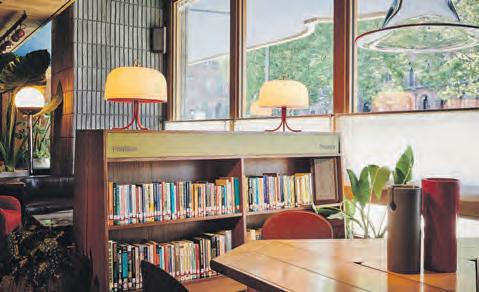

A sense of curiosity and wit is palpable in all of Carrie Maclennan’s projects – she introduces her role as Concept Librarian at The Standard, London

Interview: Stacey Hunter

For the past year Carrie Maclennan has been creating both her dream job and an intricate and strange hotel library where 28 different sections are labelled with topics such as Hope, Pets, Chaos and Mathematics. A place where guests should expect to find books with titles like Salads or Sybil: The True Story of a Woman Possessed by 16 Separate Personalities. In design, the phrase ‘doing it for the love of it’ doesn’t always acknowledge things like paying the rent but Maclennan’s story illustrates that staying true to yourself – as well as following your heart – can deliver you to your passion project. “I joined the Design Team in Feb 2019 and began building upon the ‘public library’ concept dreamed up by designer Shawn Hausman and the in-house team at The Standard, London. I started referring to myself as ‘Concept Librarian’ which has kinda caught on!” explains Maclennan. “The hotel is in what used to be the old Camden Town Hall Annex. The original building opened in 1974 and the building as it is now still speaks to that mid-70s-intothe-80s time.

“The concept was built around this story – partly truth but mostly fiction, that when the council offices closed, the public library was abandoned but left intact. At the time King’s Cross was pretty gritty. Lots of squats. We pretended that squatters had commandeered the old library and ‘made it their own’. We pretended that artists, punks, political activists took the space and reinvented it as their own.”

Accordingly, the Politics section sits next to the Tragedy section. And the Tragedy section is actually yet more books about politics. Romance sits next to Technology in a nod to the nature of modern dating. For Maclennan, the stories that run through these section headings and shelves that she has themed around music, art, design and fashion are highly personal.

“I mashed up the idea of the squatters, and what they might do with the space, with vibes that sit at the heart of what The Standard, London brand is. And I mashed up my own biography and how I was feeling about myself and the world at the time. It felt like the most exhilarating thing I’d ever done. “It was such a weird scenario in that I felt that somehow lots of things I was interested in and truly loved had aligned into this one amazing project that I was in complete control of. From reconnecting with academic texts I’d read or meant to read during that part of my life, to finding humour in crazy titles or subject themes to choosing covers based on excellent typography, crazy colourways and bonkers photography.”

Originally from Glasgow, Maclennan moved to East London in 2012. In her previous career in marketing, she felt a serious disconnect.

“I didn’t really feel like myself – fragmented in a way. What Photo: Courtesy of The Standard, Lodnon

I was doing for work and money felt at odds with my heart and my brains,” she says.

Her lifelong obsession with creating stories through objects led to the creation of Not The Kind, an online gallery and gift shop.

“Not The Kind was borne out of frustration, really. I needed an outlet to experiment and be silly and do what I wanted. When I first started I did have this dream of it being something that I could earn a living from... but it didn’t take long for me to figure out that that just wasn’t going to happen. Not with the time I had to invest in it, the little money I had and the masses of energy I’d need to devote to doing it on my own.

“At that point, I was really struggling, both in terms of my mental health and in terms of who or what I was and what I wanted to be work-wise. But in January 2019 I decided that I would give Not The Kind a proper bash.

“Now this is going to sound quite strange... but I got my tarot cards read for the first time that month. The reading, 100% contrary to how I was feeling at that moment, told me I was going to get everything I was wishing for, that work-wise I would find my place, that everything would be super successful and that I’d make money etc., etc… Crazy positive. Even the tarot reader was like, ‘Um... This never happens...’ I took it all with a massive pinch of salt because it seemed to me at that time completely impossible for things to turn around so dramatically. “I got the call from The Standard, London literally 5 weeks later and I started work there right away. Every. Goddam. Thing. Was true.”

Maclennan says the role has given her a whole new perspective. Principally, realising that she has skills she didn’t know were valuable.

“As a non-designer, I think I bring a unique perspective to my team – different insights. I have the itch to pull all the strands together: the brand; the marketing; the events; the objects; the stories; the design; the art; the publishing; the EVERYTHING! And I don’t have to pretend to be someone else. I can be interested in what I truly love. I can like what I like and I can share my taste (as jarring as it can be sometimes!)

“I’ve curated the library, I made a pop-up library for Frieze London, I concepted Christmas and now I’m launching retail. Dreams I didn’t even know I had have come true.”

Like all great stories, this one has highs – and even an element of magic – but refreshingly Maclennan isn’t afraid to acknowledge the lows.

“Fear of failure, perfectionism, low self-esteem – blah, blah – it’s all in there. And you know what? IT’S ALL IN THE LIBRARY TOO!”

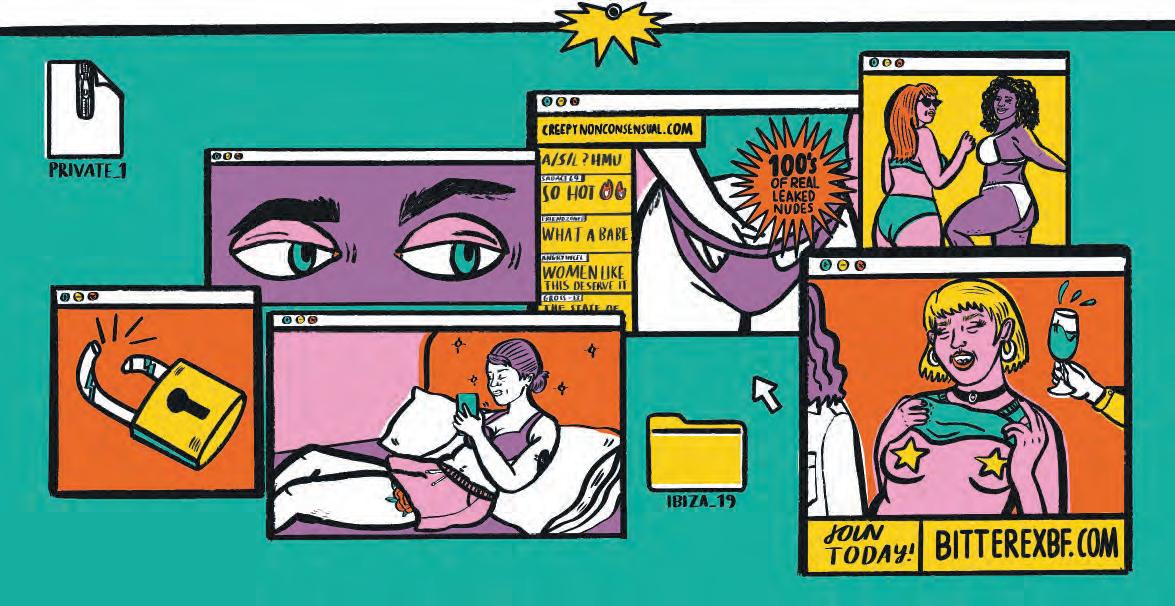

send nudes?

After finding images of herself on a revenge porn website, one writer contemplates how we can trust in the age of online dating

Words: Madeleine Dunne Illustration: Jacky Sheridan

“O h fuck, shes hot. bikini? nudes?” That was just one of the tamer comments that littered the revenge porn thread I found myself on a few weeks ago. I’d been sent the link by a friend and when I followed it, I found myself scrolling through a website saturated with girls’ images, both sexually explicit and fully-clothed. Over a six-month period, my images had been posted regularly – all fully clothed, taken from my social media and most with my name, location and age attached. Each image had replies commenting on my weight, detailing what they’d like to do me and always requesting that someone provided more. I felt sick.

So-called “revenge porn threads” have become rampant in the last few years, from the notorious Anon-IB, connected to the huge iCloud leak of celebrity nude photos back in 2014, to lesser known strains operating in a similar manner. In these threads, individuals trade images of women paired with information that makes them easy to identify. The users of this site operate under a veil of total anonymity, something that makes the situation even more disconcerting.

When Ams found that paid-for content from her OnlyFans account was being shared in a similar thread, she believed she was targeted specifically for being a sex worker. “I got sent the link to the thread multiple times by different people. I was pretty pissed, but I realised it was older content or screenshots of my page, some paid-for content was distributed but I felt prepared for it to happen to me one day,” Ams told me. “That website loves to target sex workers, so it wasn’t entirely shocking.

“I know I have to be very wary now: I send my terms and conditions religiously, I never do any business that’s not on OnlyFans and I watermark my stuff,” she explains. “The website is no help, you can send them emails all you want but it gets you nowhere so I don’t waste my time anymore.” Image-based sexual violence often goes hand-in-hand with a rhetoric that blames victims for taking and sharing the pictures in the first place. Yet, for many, sending nude images has become a fundamental part of love in the digital age. For people who use dating apps or social media to find partners, the term “send nudes” is such second nature that it’s become immortalised in online culture as a meme. The act of sending a naked image isn’t taboo – it’s become a part of the seduction process.

For Holly, sharing nude images with a partner was an important part of expressing being comfortable with that person. Unfortunately, they endured two experiences with revenge porn: the first, in a thread similar to the one I was shared on, and the second from an ex-partner.

“A girl had taken a photo of me being daft and exposing myself at a party and shared it on her Snapchat. It ended up being screenshot and posted anonymously in a thread,” explains Holly. “It was awful, but I was more mortified that something that was just a silly photo of me and my friends became twisted into a sexual subject when I was 15.”

“I had a more personal experience a few months after I split up with my ex,” says Holly. “He showed his bandmates a video he had on his phone of us having sex when he was drunk. When I found out about that, I had a panic attack.” For Holly, the experience of enduring two instances of image-based sexual violence distorted their perception of sharing images of their own body. “There’s no medium ground; I’m completely private or I put myself out there so advantage can’t be taken. I feel like no one would care if I had a smooth genital-less mound – there are people who would still find a way to objectify me no matter what, as a way of ‘putting me in my place’.”

The Abusive Behaviour and Sexual Harm (Scotland) Act came into effect in 2016, making it an offence to disclose, or threaten to disclose, intimate images or videos of people without their consent. People convicted of sharing intimate images without consent could face up to five years in prison. But as rife as these threads are, they operate as global websites and are unlikely to be prosecuted under such laws.

The goal of image-based sexual violence is to tell its victims that they have no control over their own body. That message is only reinforced when the perpetrator operates anonymously, often untraceable and safe from the very legal powers which have been put in place to protect their victims.

Watching my image and personal information be shared for months without my consent in such a disconcerting context has left me feeling anxious about how I present myself online. It’s an anxiety mirrored in the thousands of faces that filled those websites alongside mine. All with our privacy invaded and all instilled with the message that online, our bodies aren’t our own.

— 27 — February 2020 — Love Stories

Summer of Discontent

The Inbetweeners star Simon Bird introduces us to his debut feature film Days of the Bagnold Summer, a sweet comedy focused on the precarious relationship between a well-intentioned librarian mother and her metalhead teen son

Interview: Josh Slater-Williams

Best known for his leading roles in The Inbetweeners franchise and the still ongoing Friday Night Dinner, actor Simon Bird delivers a gentler comedic offering with his feature debut as a director, Days of the Bagnold Summer. It’s a sweet coming-of-age film that examines the wobbly relationship between a mother and son over one long summer in the suburbs. Mopey metalhead Daniel Bagnold (Earl Cave, son of Nick) was meant to be spending the season in Florida visiting his dad, who has a new partner expecting a baby. When the trip is cancelled, his well-intentioned librarian mum, Sue (Monica Dolan), attempts to both entertain the introverted lad and help him get his act together, while also trying to come out of her own shell.

We meet Bird at Switzerland’s Locarno Film Festival in August 2019, where his modest film, perhaps incongruously, had its world premiere at a night-time outdoor screening in the Piazza Grande, which seats about 8000 people. “I’m a bit of a control freak,” he says of his move into directing, having made one short before this. “I like being involved in something from the initial germ of the idea to its final thing. That became apparent when I started acting in stuff. I had the dawning realisation that acting actually is such a small part of the process of getting something made and there was so much I was missing out on. And it’s all these other elements that I really love. I love the script development, the casting process, the edit. It’s so, so satisfying to be involved in every element of making something.”

Co-starring Alice Lowe, Rob Brydon and Tamsin Greig, Days of the Bagnold Summer is adapted from an 80-page graphic novel by Bristolbased illustrator and filmmaker Joff Winterhart, which was released to strong notices in 2012. “My wife [Lisa Owens, the film’s screenwriter] bought me the graphic novel as a present one year,” Bird tells us. “I read it, absolutely loved it and recommended it to a lot of people, and then forgot about it and moved on with my life. And then when I was scrambling around looking for an idea of what my first feature might be, it popped out at me from the bookshelves. Initially, I thought it was actually a really bad idea because it’s such a slight book. Part of what’s brilliant about it is it’s so understated and economical, but I didn’t think there was enough in it to translate into a film. And some might argue there isn’t!

“The film itself is obviously a very small film,” he continues. “Even time-wise, it’s only 86 minutes. But while the subject matter is very small, it’s actually much bigger than the book. The book is tiny. It’s lots of little vignettes and there’s really no story to it at all. Lisa has done an amazing job of drawing what story there is out of the book.”

Was there any tension involved in his wife being the screenwriter of his debut feature? “It was surprisingly easy,” Bird says. “Well, not surprising because we get on very well! But there were definitely discussions at the get-go about whether it was a good idea, and I think the consensus was it probably wasn’t, but we decided to do it anyway. I knew that I love Lisa’s writing and that she would be true to the tone of the book that I loved. That felt like a really strong starting point and it seemed crazy to have to go through the whole process of finding somebody else who might end up being a lot worse. So, the script development was amazingly straightforward and there were no marital bust-ups.”

In contemporary reviews from the likes of The Guardian, Winterhart’s comic received favourable comparisons to the work of Raymond Briggs, in both writing and art style. Although there is a shared sense of minimalism, there wasn’t a conscious attempt by Bird to make the film visually resemble its illustrated source material in the vein of fellow Brit Edgar Wright’s admittedly more hyperactive and maximalist Scott Pilgrim vs. the World. That said, he suggests such a plan was briefly on the cards.

Photo: Rob Baker Ashton

“I’m a bit of a control freak. I like being involved in something from the initial germ of the idea to its final thing” Simon Bird

“It was definitely a consideration when we decided this was the story to tell,” he recalls. “I think my original vision for it was much closer to the book. We talked about doing a square aspect ratio like the square panels in the book and talked about doing it in black and white – just making it a scuzzy, grungier affair. For various reasons, we decided that wasn’t the best route. The main one being that what I love about the book is that the explicit point of it, stated in the first line of the book, is to tell the story of two ordinary people whose story wouldn’t normally be told. And it felt a shame to be doing that in film form, with everything that a big screen has to offer you, and then to not fully celebrate them and not give them all the credit they deserve. We ended up doing the opposite of what my original idea was: full colour and widescreen to properly glorify them.”

Not to disparage any other films in particular, but one of Days of the Bagnold Summer’s many pleasures is that it’s a modern British comedy that has actual noticeable thought put into its blocking, compositions and all the things that can feel rare in a genre where improvisation and finding the scenes later on in an edit seems to be the dominant mode of mainstream comedy storytelling. “I think that’s just something that I find hard not to do,” Bird says. “That just comes from the films that I love, lots of which are quite old. A lot of the films I love are comedy-dramas from the 70s, early-80s, like films by Elaine May, Mike Nichols and Peter Bogdanovich. And a lot of those films are very formal, quite classical in their composition. There’s something about that aesthetic that really appeals to me. It feels like when you go to the trouble of making a film, you should be thinking about what every frame looks like.”

Accompanying the visuals for much of Days of the Bagnold Summer’s runtime is a soundtrack by Belle & Sebastian, comprised of various new songs alongside some re-recorded favourites. The band’s frontman, Stuart Murdoch, made his own directorial debut with God Help the Girl in 2014, and Bird suggests his musical collaborator’s prior experience with filmmaking was of great benefit:

“Stuart was amazingly involved and definitely had learned from his own experiences, both of directing his film but also for having done music for film before. I think he knew the pitfalls and wanted to avoid them. And I think the way to avoid them was to have conversations very early in the process. Amazingly, he got me the music before we filmed the film, which is sort of unheard of. That enabled me to have to crystallise the tone in my head and know roughly the style of stuff that we’re going to be fitting to the shots, which obviously is going to make the whole thing feel more coherent. Well, hopefully, is the idea.”

Days of the Bagnold Summer has its Scottish premiere at GFF on 4 Mar, 6pm, with a second screening on Thu 5 Mar, 3.45pm

— 29 — February 2020 — Feature

It’s a death trap

Shell and Iona director Scott Graham returns with third feature Run. Sitting down with The Skinny and some of the film’s cast, Graham tells us how his tale was inspired by a visit to his hometown and the story of a Bruce Springsteen obsessed fisherman

Interview: Carmen Paddock

Run, the third film from Scott Graham, captures the restlessness of small-town Scottish life through the eyes of a former boy racer, who seeks one final night on the road before facing his very different life back home. We caught up with Graham and his Run cast members – Mark Stanley, Amy Manson, Anders Hayward and Marli Siu – at the London Film Festival last October. Sitting down with us in the cafe at the Vue Leicester Square, Graham speaks passionately about his influences, citing a trip home to Fraserburgh, Aberdeenshire about 15 years ago when researching a short film about boy racers. When there, he heard a local story about “a fishwife leaving her husband because he was listening to too much Bruce Springsteen.” The tragicomic scenario sat with him until he was ready to make Run. “I wanted to get it right and let it percolate in the background,” Graham recalls, “sometimes you know and you’re thinking about them even if you’re working on something else.”

The cast was drawn to the story through the immensely recognisable, relatable characters Graham created. Manson and Siu grew up nearby, and both recognised their friends and families in their characters Katie and Kelly respectively. “That was amazing to get a chance to be a part of something that felt so authentic and so real to your own upbringing,” Siu says.

Lead actor Stanley doesn’t hold back with his praise, citing the “amazing, nuanced, human thing about people I knew – stuck in the cycle of their hometown” as an immediate source of connection. “They’ve nailed their colours to the mast and that’s it,” he says, “and they’re either going to thrive in that or they’re going to get depressed with the limited options, so I could connect to it straight away.”

The cast readily admits that another main draw to the project was Graham’s script and the collaborative nature of his work. “I tried to write something that when we all came to do it we would recognise the place,” Graham says, adding that he had to be ‘careful’ with the portrayal “because it’s my hometown.” He felt it important to get the actors on location from the early stages to absorb the atmosphere and spend time together – and in Stanley’s case, so that he could learn to fillet fish (thankfully, a success). “I wouldn’t really call what we did rehearsal,” he says. “We just got together and talked about what was happening; it was really nice.”

Aside from the local flavour and the initial Springsteen anecdote, Graham wanted to bring the focus of a good Raymond Carver story. “[Carver] never wrote screenplays but I think he could have written good screenplays because so much of it is about using the smallest number of words and then giving it to people to fill in the gaps,” Graham says.

“Scott’s writing unfolds itself in a way you can read over it and over it and over it and some things he writes so simplistically but that allows for numerous ways of doing it,” Stanley adds.

Hayward agrees: “There was no filler, everything was so concise and necessary; every word was important, everything that a character said was revealing something about their character or hiding something about their character.”

A key portion of the film takes place when Finnie and Kelly share a midnight ride around the town. “It was amazing to get to act in that environ

ment because the camera was in the back of the car a lot of the time so you just forget, and because Mark’s driving the route the whole way through the film, you can escape the way that sometimes when a camera’s here you get a bit self-conscious,” says Siu. “It’s like theatre: you’re just sitting there getting to act and totally escape any feeling you’re on a set as you cruise around, and then Scott would be in a car behind shouting stuff every now and then.”

While she had a great time, the logistics proved trickier. According to Graham and Stanley, DOP Simon Tindall was “getting thrown left to right” in the back of the car as Stanley tore through the streets. The finished product, with skilful sharp and soft focuses on faces and streets as appropriate, shows no sign of this chaos. The car, however, did not survive. “We blew two exhausts on it; we ruined this car,” Stanley says, “but the nice local guy who gave us the car and did all of the restorations on it was fine with the fact that we killed it. It’s being rebuilt.”

Run has its Scottish premiere at GFF on Sun 1 Mar with a second screening on Mon 2 Mar

The Best of the Fest

Family feuds, apocalyptic absurdism and hard-hitting historical drama – here are our picks from the GFF programme

About Endlessness Swedish absurdist Roy Andersson returns with this eerie, dreamlike and apocalyptic series of vignettes set in a topsy-turvy world. The film won Andersson the Silver Lion for best director at the Venice Film Festival last year; GFF hosts its UK premiere. 2 Mar, 9pm and 3 Mar, 3.45pm, Cineworld Renfrew St

Martin Eden Another hit from Venice, Pietro Marcello’s adaptation of the Jack London novel follows the sailorturned-writer as he aims to transcend his humble origins. A vast, multilayered story anchored by an award-winning central performance by Luca Marinelli. 28 Feb, 8.30pm and 29 Feb, 3pm, GFT

Patrick Peaky Blinders director Tim Mielants makes his bigscreen debut with Patrick. The eponymous lead works as a handyman at a naturist retreat, hit with the one-two punch of his father’s death and the theft of his favourite hammer. A mixture of deadpan comedy and family drama, starring Belgian actor Kevin Janssens and Jemaine Clement. 27 Feb, 3.30pm and 5 Mar, 6.15pm, Cineworld

Radioactive Persepolis writer-director Marjane Satrapi is back with another graphic novel adaptation, this time taking on Lauren Redniss’ biography of Marie Curie. Rosamund Pike stars as the Nobel Prizewinning physicist; the film follows her career, and the enduring legacy of her work. 6 Mar, 6pm and 7 Mar, 1.30pm, GFT

Moffie Oliver Hermanus returns with a masterful film following a young man drafted into military service in early-80s South Africa. What makes life even tougher for our protagonist is that he’s gay, and in the Apartheid era, homophobia goes hand-in-hand with racism. Hermanus’ command of sound and image is virtuosic and wholly enveloping. 2 Mar, 8.45pm and 3 Mar, 1.30pm, Cineworld

Our Ladies Michael Caton-Jones’ adaptation of Alan Warner’s novel – which follows six Catholic choir girls from a small coastal town, let loose for a day on a trip to Edinburgh – has been long in the making. There’s rambunctious chemistry and some impressively crude banter from its ensemble cast, with some incisive social commentary to be found as well. 28 Feb, 8.40pm and 29 Feb, 1pm, GFT

Rialto Glaswegian filmmaker Peter Mackie Burns follows up the brilliant Daphne with another nuanced portrait of a life in freefall. In this case, a Dublin dock worker begins experimenting with his sexuality with a younger man while his home and work life slowly implode. Burns once again shows himself to have a deeply cinematic eye for capturing existential malaise. 27 Feb, 8.30pm and 28 Feb, 3.45pm, GFT

The Truth Shoplifters director Hirokazu Kore-eda makes the move to Europe with an all-star cast. Catherine Deneuve plays an old-school Hollywood diva, confronted by her estranged daughter (Juliette Binoche) and son-in-law (Ethan Hawke) who have a bone to pick over Deneuve’s less-than-truthful memoirs. 3 Mar, 6.15pm and 4 Mar, 3.45pm, GFT

The Painted Bird This adaptation of Jerzy Kosinski’s WWII novel has prompted rave reviews, comparisons with the work of Andrei Tarkovsky, and a raft of audience walkouts. Jet-black in both style and substance, by all accounts it’s a harrowing but compelling look at one child’s journey through a physically and psychologically battered Eastern Europe. 1 Mar, 8pm and 2 Mar, 4pm, Cineworld Women Make Film Mark Cousins’ new film is an epic in every sense of the word. The five-part, 14-hour documentary explores cinematic history exclusively through the gaze of women filmmakers. From visual style and characterisation to genre films and cinema’s approach to life and death, Cousins aims to reshape and redefine our cinematic canon. 6, 7 and 8 Mar, various times, Cineworld

— 31 — February 2020 — Feature

Personal is Political

The Royal Scottish Academy’s selection of the most recent art graduates, New Contemporaries returns, including some timely works from emerging artists keen to confront social issues and political tumult

Words: Adam Benmakhlouf

Katherine Fay Allan the rest of us... we just go gardening Allan found this title in the work of a neurosurgeon describing how he thinks of surgery as a process of removing bad growths and promoting good growths. For Allan, this was an evocative way to understand medical care, and inspired the plants that are at the centre of her installation and performance. She includes evergreen plantlife as an interruption to the sterility of the hospital bay, incorporating what has been proven as the healing and grounding presence of greenery.

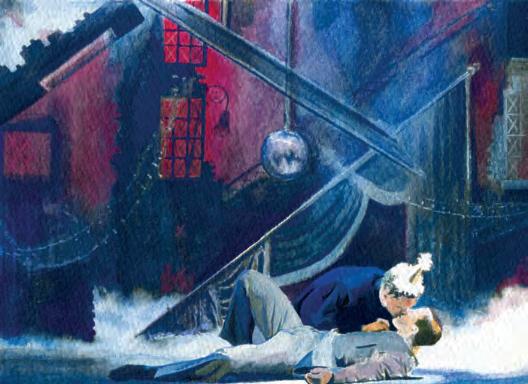

Alex Hayward When He Held Me In His Arms I Forgot the Past A night at the ballet became the catalyst for the degree show series of paintings, drawings and collages that Alex Hayward made after seeing Matthew Bourne’s Cinderella. These works made their way to Bourne’s social media and Hayward was invited to make new work in response to Bourne’s new production of The Red Shoes, which will be shown for the first time at RSA NC. For Hayward, these images of the theatre carry a comforting and old school campness, full of romantic longing.

Ruby Pluhar Ella At Glen Coe’s Magic Hour “I amplify the qualities that I pick up on in my subjects to sculpt a feeling of them and their story. I am drawn to shoot in natural locations for its many changing colours, lights and textures.”

The photography of Ruby Pluhar documents her friend and collaborator Ella, as they spend time in Scottish landscapes. In striking colours and powerful juxtapositions that combine Ella and dramatic backdrops and natural sites, Pluhar creates dramatic contrasts in tightly composed and enchanting images.

Bibo Keeley House on Fire (Detail) Local lore and classical-mystical German music forms combine in Bibo Keeley’s sonic exploration of the rugged areas of Scotland. Recordings of her own sung improvisations are woven into ambient sounds of rain, seabirds, wind and waves. “The key themes informing my current work are the urgency of climate crisis, my personal experiences of the fragility of life (my partner’s near-death and heart transplant) and the divisiveness of Brexit. I respond to the disharmony in global climate efforts, alarming political polarisation, and the need for healing.

Jasmine Regmi

Gabrielle Gillott Safe Haven For many of the exhibitors this year, the majority of their final years were framed by Brexit votes and extensions. In Gabrielle Gillott’s exhibition, she draws on his research in stockpiling forums to create a series of sculptures of sparse interiors in which the forms of tins and dry goods spill out from unexpected places. For Gillott, the hoarding is one of the the most distinctive physical expressions of general social insecurity surrounding Brexit.

Alison Campbell Glass

Jasmine Regmi Installation shot Jasmine Regmi’s paintings emerge from research into the Indian miniature and the treatment of young girls in Nepal. In one series of panels, she considers the treatment of Kumari, young girls who are treated as goddesses then cast out of home when they have their first period. She says: “There are many things that motivate me. I love reading stories and news about all the events that happen and it creates a rage inside of me seeing women that are vulnerable in this day and age which drives my work ethic while creating my pieces.”

Méabh Breathnach Untitled While other exhibitors look to exceptional circumstances and unusual narratives, Méabh Breathnach uses complicated casting and ceramic processes to transform familiar forms into elegant and evocative sculptures. For a new body of work especially for the RSA, Breathnach has made tiles that incorporate strands of hair which break down and become ‘unique and playful lines’ after being heated to high temperatures, as well as a picture rail made from the profile of Breathnach’s face, and bronze sculptures of a cardboard box, three house plants and a chopped off plait of hair.

Shilei Fan Remote and Control Working with the repeated form of the games controller, Fan’s work repeats the symbol of control in an installation that is intended to be an immersive and oppressive experience for the audience. An accompanying video displays images of destruction and animal documentary, as glitches and pixelation distort the film, and the imagery changes quickly from a lion eating a fresh carcass to the BBC news intro. For Fan, these are artistic means of reflecting on the “cultural dilemma of globalisation” and “information manipulation.”

Alison Campbell Glass ‘Plethora’ and ‘Portrait of George Drever’ Bringing political education into the gallery space, Campbell Glass will display sculptures and videos that represent parts of her family’s tradition of being very politically engaged and active.

“In a way the political orientation is irrelevant, it’s the concept of archiving the stories and the physical collections that may interest some… political education is highly necessary in the current political climate. Especially in environments like art spaces where class consciousness is usually weak, and commonly the upper class control and curate the spaces we are trying to break into.”

Dancefloor Destiny

In the wake of her latest record Seeking Thrills, we speak to beatmaker and pop producer Georgia about dancefloor escapism, dodgy 80s dance music and finding a place of one’s own

Interview: Cheri Amour

When your dad is one half of pioneering electronic duo Leftfield, it’s possibly not surprising that you’ll be curious to make your own beats. But for Georgia Barnes – known mononymously as Georgia – making music has always been about something bigger. It’s about feeling part of something, losing your inhibitions and getting lost in that moment. “Seeing people on the dancefloor, and seeing them having that release, inspired this album. The love that people have, why people go to dancefloors; ecstasy, euphoria, but also escapism,” she tells us over the phone from the winding lanes of an overcast Brighton.

Barnes will be performing tonight as part of a string of intimate record store performances to mark Seeking Thrills’ release – a record that she believes represents a new pace and rhythm for her and her longstanding team. “It feels different from last time; it’s like there’s a new energy,” says Barnes. “We’re all saying how this feels like the start.” To truly go back to the start with Georgia you have to head to leafy central London, where Barnes grew up, in her mum’s cooperative flat. Alongside her passion for football – as a child she played for both QPR and Arsenal’s under 17s women’s squads – Barnes began attending The BRIT School, something she believes was instrumental in shaping her identity.

“Everyone goes on a personal journey when they go to school. School’s just a shit place. It doesn’t matter what kind of school it is, school is school, and at that age group especially it’s a really hard time for people,” she acknowledges. “The BRIT School was a great place for me as I met so many of my best friends, and people who were interested in the same things. It was a place where you weren’t going to get bullied or seen as a weirdo.” Far from it, the performing arts institute has been the bedrock for so many who have felt seen and liberated. From discordant noiseniks black midi to ethereal pop majesty FKA twigs, The BRIT School is so much more than a fame academy.

Yet for all the innovation and imagination between its walls, Barnes left feeling a little discouraged. “After BRIT School, I went through a bit of a ‘I don’t want to hear Western pop music’ moment so I went straight into a university BA degree in ethnomusicology at SOAS.” It was here that Georgia learned the kora (a West African harp) and spent a short time training on percussion in Cuba. To make the leap into solo artistry though, Barnes knew she needed to be financially independent. The compromise? Session drumming.

“It feels different from last time. It’s like there’s a new energy. We’re all saying how this feels like the start” Georgia Barnes

Picking up work with Young Turks’ producer and songwriter Kwes, Barnes became an integral part of the South London music scene. Notoriously, she went on to join longtime family friend Kate Tempest’s touring line-up for the Mercury Music Prize-nominated Everybody Down. “My mum and her auntie are best friends, they were social workers together in the 80s,” she says. But even drumming more regularly with awardwinning artists doesn’t mean impostor syndrome can’t strike, as Barnes admits she increasingly felt like an outsider. “I was an observer really. I always felt like I wasn’t worthy. They’re so talented; like who am I? I was just known as the drummer. No one really knew I was making music on the side and sometimes Kwes would ask me: ‘Come on, play me some of your music’ and I was a bit embarrassed.”

Of course, there was no need for Barnes to feel self-conscious. Georgia showcased her talent for grime-spiked anthems, with the music media heralding her as the ‘sound of youth’. But, as Barnes tells us, Seeking Thrills is really the beginning. A lot has changed since her first release, after all. She did all the things we aspire to do but never pull off: she quit drinking alcohol, became vegan and went gluten free. The DIY trappings of her debut have been replaced with sharp-eyed pop ambition, inspired by 80s Chicago house and Detroit techno – something she’s not ashamed to admit has a bad rep. “There was a lot of crap in that decade, let’s not beat around the bush. But there were also incredible things going on with technology when digital met analogue and all these artists [were] really pushing the boundaries of sound recording.” That’s what you’ll find in Seeking Thrills. From the sensational About Work the Dancefloor, which could give Robyn a run for her money to the genius cameo of South London vocalist Shygirl on glitch-grinding Mellow, Barnes is perfectly poised. For all her hide and seek to get here, it feels like Georgia Barnes has found a place of her own, surrounded by love and a dancefloor glow.

As she puts it in the M.I.A.-esque Ray Guns: ‘Let your light shine up to the sky / Light up the night / Be who you will be collectively and perfectly’. Seeking Thrills rises up like a flare gun to mark Georgia’s ascent towards that collective perfection.

Seeking Thrills is out now via Domino

Army of One

Faced with personal and geographical upheaval, MALKA’s Tamara Schlesinger looked inward to summon her most striking and sanguine solo statement yet

Interview: Joe Goggins

“T he difference this time was that I didn’t want to be a character any more. I wanted to be me.” For Tamara Schlesinger, that’s amounted to a musical reinvention. It’s meant expanding beyond the deliberately narrow parameters she set for herself when she first struck out solo as MALKA, after the apparent dissolution of her old band, folk five-piece 6 Day Riot. It’s meant opening herself up to the possibility not only of bringing in outside help, but of genuine collaboration, something she’d done her best to hive herself off from since going it alone.

It’s involved genuine introspection, too, and the tackling of her own thoughts and feelings head on, rather than leaving them to one side whilst she concerned herself with the issues of the wider world. The axis around which the transformation has revolved is a casting-off of concerns about the opinions of others, and the unapologetic following of her own path.

I’m Not Your Soldier, then, is an appropriate title for this third MALKA full-length, one that sees Schlesinger very much the commander-in-chief of her own creative army. It’s arriving via Tantrum Records, which she runs single-handedly; sometimes sunny and sometimes stormy in its sonic makeup, it’s thematically an irrepressibly positive paean to self-empowerment, independence and grace under pressure.

After years in London, where 6 Day Riot were based, Schlesinger has returned permanently to her native Glasgow. The decision was sealed in part by her desire to work with the renowned producer Paul Savage, who now adds MALKA to a CV that reads like a who’s who of Scottish indie royalty, running from Franz Ferdinand to The Twilight Sad via Mogwai and King Creosote. “Paul was a big factor, but I was also really eager to embed myself back in the scene here,” she explains. “I’m Not Your Soldier is my coming home record in that sense, but it’s obviously the start of a new chapter of my life and career too.”

Key to that has been a marked change in musical direction. When Schlesinger first began work as MALKA, she was sufficiently keen for a clean break from the twinkly acoustic fare that represented 6 Day Riot’s calling card that she disregarded traditional instrumentation entirely, instead making beats and samples the basis of her palette on 2015’s Marching to Another Beat and its 2017 follow-up, Ratatatat. “I’d been running away from 6 Day Riot a little bit, not wanting to be defined by that sound, and I think this time I finally felt comfortable enough in my own skin to pick up instruments again and find a happy medium,” Schlesinger admits. “A lot of the demos were done in my home studio, so it was a case of picking up and using whatever was around, whether that was an acoustic guitar I hadn’t used in a while, or my kids’ toys off the floor.”

Schlesinger is a mother of two and that’s something that hangs heavy over I’m Not Your Soldier. The dreamy final track, Close Your Eyes, serves a double purpose as a lullaby, whilst the abundance of playful vibrancy elsewhere (I Know, You Know and Don’t Leave Me, especially) evokes the kind of striking melodic simplicity you might associate with nursery rhymes. Get Up, meanwhile, is a triumphant reflection on the poise with which she’s juggled the personal and the professional in recent years.

“My eldest is seven now, and when she was born I remember being really nervous about whether I’d be able to carry on making music,” Schlesinger tells us. “I wondered whether I’d be able to handle being a mum and this workload of writing and running the label, and I didn’t know whether the inspiration was still going to be there – I was scared it might dry up. Even recently, coming back up to Scotland, it was a daunting prospect to start afresh, and Get Up is really about how everything feels like it’s aligned in this lovely way. It’s a struggle at times but I know now that I can manage it – I can be a good mum and be creative. They don’t have to be exclusive.”

Her success in terms of that particular balancing act seems to have brought about an equilibrium in everything for Schlesinger. I’m Not Your Soldier is a record defined by the measure in its musical choices and by a palpable emotional stability, one that lends an innately upbeat air to proceedings. “It’s so easy to focus on the negative, especially at the minute,” she says. “You look at the world, and there’s no shortage of things to bring you down. I just feel like there’s so much magic and joy to be found in the little things within your own life, and the more I worked on the album the more I felt like those were the ideas I wanted to put forwards. I’m glad I did.”

I’m Not Your Soldier is released on 28 Feb via Tantrum Records

MALKA plays Stereo, Glasgow, 6 Mar

malkamusic.co.uk

Radical Art

We catch up with the folk from The Workers Theatre about radical art, how a theatre cooperative works and why their upcoming festival, Something Has To Happen, couldn’t be more timely

Interview: Eliza Gearty

‘T he Workers Theatre rejects privatised profit as the enemy of good art.’ ‘Our art will be committed to the liberation of all people,’; ‘The Workers Theatre will be populist but not shit.’ These are just a few of the statements from a Manifesto written up by the Workers Theatre in 2017 – when a group of artists, tired of the constraints that came about from working with funding bodies and institutions, got together to take matters into their own hands. Their first project, Megaphone, aimed to crowdsource £11,000 to provide a residency for artists of colour; the project resonated, and they exceeded their target by more than £1000 (their success was covered in this magazine).

Shortly afterwards the collective staged their first festival, The Workers Theatre Weekender, featuring works-in-progress by the recipients of the residency alongside a variety of shows, workshops and talks. Now they’re back, with their second festival, Something Has To Happen, in the works. Taking place in Glasgow’s Southside from 12-16 February, the festival has some great events programmed, including a staging of Mara Menzies’ critically acclaimed Blood and Gold, a relaxed performance of new material from Josie Long and a couple of free breakfasts (we’re sold). We chatted to two members of the collective, writer Henry Bell and actor Beth Frieden, to find out more about the cooperative, the festival and why radical theatre has an important role to play in the resistance.

Could you tell us a little bit about how The Workers Theatre started – where the idea came from, and how it was put into action? Henry Bell: The Workers Theatre came about for a couple of reasons. One was the lack of access to rehearsal and performance space in the city after the closure of The Arches, and the other was the feeling that decisions about what art should and could be made were increasingly the preserve of managers and funders, not arts workers. So as a group of artists, actors, writers and producers we came together with the vision of creating a space for radical theatre in Glasgow.

What makes The Workers Theatre different to other theatre companies? Beth Frieden: We are a cooperative! This means that members are owners of the company. The structure is horizontal, so decision-making power is shared. We can take different roles for different projects, but we always return to an equal base. We are democratically owned and managed. We are also explicitly political in our manifesto: we want to produce art that entertains and radicalises.

Why does your upcoming festival, Something Has To Happen, have to happen now? HB: There’s never been a more urgent time for us to tell these stories and have these conversations. The rise of the far right, capitalism destroying the planet, a stultifying government re-elected to

Photo: Mara Menzies

Westminster – there’s no question that Something Has To Happen. We need some hope in the dark, and we hope that the festival will provide some space for imagining and acting out a better world.

What can audience members expect to see at the festival? BF: Comedy, theatre, music, kids’ shows, storytelling about the legacy of slavery, performance about the fragile male ego, sex worker unionisation hymns, and even a Transylvanian ceilidh.

Is there a particular reason why you chose to host the festival in Glasgow’s Southside? HB: The Southside has a population of hundreds of thousands, with relatively little arts provision. It’s also beautiful and most of us live here.

Do you think that there is a political threat to the perseverance of theatre right now? If so, how can we fight against it? BF: Radical theatre, touring theatre, and stories by and for marginalised people are always under threat in a society that values profit above people. But we can fight back by making that art, and by supporting those artists that offer us glimpses of those different worlds.

Do you think theatre has a role to play in the labour movement? HB: The labour movement is all about the stories we tell. Who we are, how we are organised, what kind of a future we want. Storytelling is one way to share ideas, and can also help serve as collective memory, to remind us of our own history and what we are capable of. Protests and direct action are often in themselves a type of theatre too. But theatre, and storytelling, and singing keeps us going in struggle. We need to have fun. We stand firmly behind the line in Bread and Roses: ‘Hearts starve as well as bodies / give us bread, but give us roses.’ We want a world where everyone has access to art and theatre, both making it and watching it, as well as shelter and food.

Something Has to Happen, various venues across Glasgow’s, Southside, 12 - 16 Feb

B2B: Aquarian x Sougwen Chung

With his debut album due for release this month, we asked DJ and producer Aquarian to discuss the making of the album and his collaboration with artist and researcher Sougwen Chung

Interview: Nadia Younes

Musician/artist collaborations are hardly a new thing, but the depth of collaboration can differ greatly. For his debut album, The Snake that Eats Itself, Canadianborn DJ and producer Chris Leung, aka Aquarian, requested the assistance of acclamée artist and researcher Sougwen Chung for its art direction.

The pair have known each other for years, and recently collaborated on Chung’s Exquisite Corpus installation, for which Leung provided the musical score. As well as providing the art direction, Chung will also be collaborating with Leung on the album’s accompanying live A/V show, currently in development for later this year.

Ahead of the album’s release, we asked the pair to discuss their separate artistic practices and how they came to collaborate on this project.

Aquarian: What’s your relationship with music? When did it start factoring into your practice and how? Sougwen Chung: Well, I have a background as a classically trained violinist and pianist. But I think music culture and its ties to the early internet had a greater influence on my current practice, especially electronic music and the visual art surrounding that really resonated with me.

I do think that’s one of the refreshing parallels about our collaboration; we both have a background in music/visuals. I have always really loved your photography, so perhaps this question mirrors yours, but I consider you to be a multidisciplinary artist. Does your background as a photographer influence your music practice at all, or are they separate? Photo: Alex Lake; Two Short Days Aquarian

Yeah, I think I’m a multidisciplinary artist, although the visual side is a lot less prominent right now. To be completely honest, I don’t think my photography influences my music directly, although they are similar sources of inspiration for both. Would you hate me if I asked what your inspirations are?

No, not at all. My photographic work was heavily influenced by a school of photography that draws its inspiration and reference from cinema, mostly staged and related to film still photographers, like Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Gregory Crewdson, Cindy Sherman, Jeff Wall...

I’ve found the medium of cinema to be a big influence on me since I was young, from the films themselves to the soundtracks. And for a period of time when I was small I’d find myself just listening to film scores. I can see your music being described as cinematic as well; the scoring work I’ve listened to of yours, definitely – it’s a kind of worldbuilding. Yes, definitely. I think it’s more about the sensibility of transportation and worldbuilding that’s important to me. Yeah, something I’m thinking about too with the AV show – what environment the set evokes, what the visual language of the textures, rhythm could be.

It makes me curious about how you would compare the process of creating a record like The Snake that Eats Itself vs composing a score for an installation. Are they similar? The outcome of the form is so different. More generally, do you have the audience in mind when writing music? Sougwen Chung, Drawing Operations (Duet)

I’d say for the LP the writing style is definitely different. There was definitely an audience or at least context in mind, moving from music geared for direct club/DJ use to something that is meant to be absorbed and not necessarily designed to facilitate partying. I’d say that function is the middle ground between ‘club music’ and something more contemplative and cinematic like the scoring. What are the challenges of creating this new A/V set vs something like DJing?

The A/V set uses the language of club music, but hopefully can speak to the audiences beyond that context. The rules of ebb and flow are a lot more loose, or rather there should be no rules. The DJ is a performer but also a facilitator; the live musician is free from the latter. I like the idea of the DJ as a facilitator. It’s weird but I hadn’t really thought about it like that until more recently, the kind of dialogue they create with the room.

You worked with Sepalcure many years ago, which was when I met you… Given the amount of time that’s passed and how your own practice has evolved over the years, what is different or the same in the way that you are approaching this collaboration? My approach to this A/V show is definitely more narrative than the work that was done with Sepalcure. I think about visuals differently than I used to, and your music has more of that cinematic arc, which in a way is more challenging.

To tie into the notion of worldbuilding too, my interests in my own practice involve a certain amount of speculation about the future, so I’d like to bring a bit of that thinking, inspiration, research into the concept of the Aquarian show, and the music speaks well to that.

The Snake That Eats Itself is released on vinyl 14 Feb via Bedouin Records

Young, Wild and... Free?

Emma Jane Unsworth writes unapologetic novels about unapologetic women. Her latest, Adults, is no different. Here, we chat messy relationships, women’s appetites and how television has become the place to be for female creators

Interview: Anahit Behrooz

Halfway through Animals, the critically acclaimed film adaptation of Emma Jane Unsworth’s novel, a fox wanders the darkened, party-soaked streets of Dublin, pausing momentarily to lock eyes with the film’s charismatic, exuberant and deeply adrift protagonist, Laura, before scarpering away. For most, it immediately calls to mind 2019’s other iconic foxy mo ment, when Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag has her own vulpine encoun ter in the show’s final scenes – an overlap that was, it turns out, entirely coincidental.

“I hadn’t seen the second season of Fleabag yet,” confesses Unsworth, who adapted Animals for the screen herself. “Our producer Sarah Brocklehurst texted me and was like, ‘oh my god, they’ve used a fucking fox!’” She laughs down the phone, tickled by the absurdity of it all. “I mean, she has a moment with the fox, we have a moment with the fox... Jesus Christ, what are the chances? So we just had to put it down to beautiful synchronicity,” she chuckles.

Synchronicity aside, it is a moment that’s perfectly suited to Animals, as both film and book linger in the wildness and viscerality of women’s lives. The story of an intense friendship between t wo hedonistic young women, the book, particularly, is a tumultuous, uninhibited read, each page soaked in wine, MDMA and desir e. “It should come with a government health warning, that book,” Unsworth says, half apologetically, half with relish. But giving expression to women’s untamed appetites and behaviours is deeply important to her. “I just love, love writing about women’s bodies and the heightened sensory experiences involved in feeling like you’re an animal. I’m so interested in that interplay, in that exchange between the wild and civilised parts of people. It comes down to the body in a glorious, joyous way that I want to enjoy, while also acknowledging that it can be a prison for women.” Her new novel, Adults, builds on this, focusing on Jenny, a

35-year-old woman fresh from a break-up and on the brink of losing her job, her friends, and her grip on her mental health. Although Adults is perhaps more obviously of the zeitgeist than Animals – the potential darkness and toxicity of social media forms a key part of Jenny’s narrative – both novels centre on millennial women in their thirties who are still entrenched in the process of emotionally and physically becoming, subverting the traditionally teenage coming-of-age story. “I suppose it’s because I feel it’s a myth that you ever come of age, I really think it’s total crap,” Unsworth laughs. “No one ever comes of age. Or maybe what we do is come of age over and over and over again throughout our lives.”

This constant process of identity formation plays out in Jenny’s relationships, much as it did in Laura’s. But while Animals zeroed in on the latter’s entwined, fiercely co-dependent friend ship with one person, Adults takes a broader perspective, incisively yet compassionately laying bare Jenny’s relationships with her mother , best friend and co-workers. In a book so thematically focused on romantic relationships, sex and loneliness, prioritis ing these female connections is an almost radical act. “I’ll always writ e about intense relationships between women because that’s what interests me the most,” explains Unsworth. “One of my favourite things to do is play around with romantic comedy tropes but put them in a different context where it’s not a man and a woman, [instead] in the context of two friends or a motherdaughter bond.” Much like in Animals, the real love story – its exhilaration, its pain, its fractiousness – is in the relationships between women, relationships that both rupture and repair.

The attention that Unsworth pays to the intimate, interior and unkempt experiences of women has drawn comparisons to Phoebe Waller-Bridge (fox and all) and Irish novelist Sally Rooney. Does Unsworth find these comparisons empowering or limiting? “I wish there were more names!” she says fervently. “I love both of them – I think they’re geniuses – and I’m so glad that their works are out in the world. But I just wish we had more voices and more diversity. I think it would be great if there were many more women that we could refer to.”

For Unsworth, television seems to be the place allowing for more diverse voices. She points to her peers, Rooney and Candice Carty-Williams, as other novelists who are adapting their bestsellers, while Adults is already set to become a television series with Unsworth on screenwriting duties. Television, she explains, is increasingly becoming a space where women can tell authentic, unapologetic stories. “I don’t like redemption stories and I don’t like super neat happy endings where everything is jolly and shiny and Hallmark,” Unsworth states firmly. “I don’t want my work to be a cautionary tale. I’ve got many more questions than I’ve got answers.” In Adults, as well as Animals, it’s a joy to hear her ask them. Photo: Alex Lake; Two Short Days

Adults by Emma Jane Unsworth is published on 30 Jan by Harper Collins

Open the Floodgates

The man with the bafflingly-titled comedy shows, John-Luke Roberts is back with a new twist on his particular brand of absurdism

Interview: Emma O’Brien

John-Luke Roberts, the ‘critically acclaimed idiot’ as his Fringe blurb memorably described him, has made a particular departure from his past work. Not in the sense of abandoning his uniquely and gleefully bizarre sketches and charac ters, but in his resolution to perform his latest show without the ph ysical props he usually utilises to bring them to life.

Given his training in clowning, this presents him with a particular challenge. Although it’s a challenge he’s set himself, he’s not concerned it will impact the show. When asked if this altered the way he wrote After Me Comes the Flood, he replies confidently that “if a joke is funny, you can always find a way to do it.” Instead, the challenge proved to be a benefit to the show’s writing, pushing him to establish how he would bring the characters into the room with the repertoire reduced to simply himself and a salmon pink suit. In fact, he mentions that he’s “not sure people would notice” the distinct lack of props. “It’s still very much my comedy,” he says reassuringly.

Roberts clearly understands the mechanics of his craft well. Although known for his impeccably crafted one liners, that’s not the only skill on display; he observes “there’s a certain level of miming that most comedians rely on” which in fact only makes sense without visuals. However, there’s a new(ish) visual challenge that’s here to stay. As someone recognised for his quickfire comedy, what’s his view on social media comedy, given there seems to be a swing towards non-comedians carving themselves a niche in that medium? “I think the issue with it is that you can have a joke, or a joke format, which works really well on Twitter,” stating memes as a good example due to their building of familiarity and layers of jokes with new voices and new hot takes. “The key is to tell a joke that can work without performance, and what you’ll find is when someone tries to translate the joke to a live perfor mance it doesn’t work in that context,” he adds.

From here we find ourselves, perhaps inevitably, discussing the role of social media in keeping us relentlessly aware of the increasingly depressing skip fire of current affairs, but Roberts is thankfully quick to reassure that “absurdism can be a great release when the world is horrible, as it undoubtedly is at the moment.”

With that in mind, does Roberts feel like he’s done anything to nurture the current wave of alternative comedy through the regular London night he co-founded with Thom Tuck, the Alternative Comedy Memorial Society? Rather than an alternative comedy showcase, he thinks that ACMS is more an exercise in the relief of absurdism which “challenges the whole idea of things making sense, which can be very comforting in a climate like this.” ACMS largely involves acts testing out new material, and more often than not comics end their set by shouting ‘Failure?!’ and the audience responding with ‘A noble failure!’. If nothing else, this seems a good metaphor for more or less every political endeavour of the last few years.

Photo: Natasha Pszenicki

Certainly, what now calls itself alternative comedy seems worlds away from the genre that sprung up in the 80s, the last time we were all pretty much convinced the world was about to end. Roberts touches on the mooted return of Spitting Image and musing that perhaps in its final days there was nothing of consequence left to satirise. “When you’re stuck in that obsessional news cycle and feeling there’s nothing to be done, it might be good for comedy to move away from that, and focus on stupider things,” he says. “Surrealism might hopefully get you looking at the world a little differently.”

Roberts, thankfully, steadfastly refuses to be defeated by this. “If all you do is think about how horrible things are, life isn’t really worth living,” he says. “Comedy is hopefully a really good way of getting you out of that. If you challenge the very idea of things making sense, you can hopefully smile at things not making sense.”

Second Hand News

2020 started with the US assassination of Qassem Soleimani, throwing Iran into turmoil and causing World War III to trend on Twitter. Here’s what watching the news unfold felt like to this second-generation Iranian immigrant

Words: Anahit Behrooz Illustration: Kimberly Carpenter

Ispent the third day of this new decade on a train to Edinburgh, staring blankly out of a window and constantly refreshing the news on my phone. In the early hours of that morning, Qassem Soleimani, the Islamic Republic’s leading military figure and the most powerful person in Iran after Ayatollah Khamenei, had been killed in an illegal drone attack in Iraq on Donald Trump’s orders. Iran had vowed retribution, Trump was reacting in a classically deranged manner and World War III was ghoulishly trending on Twitter. As a second-generation Iranian, all I could feel was a numb kind of panic.

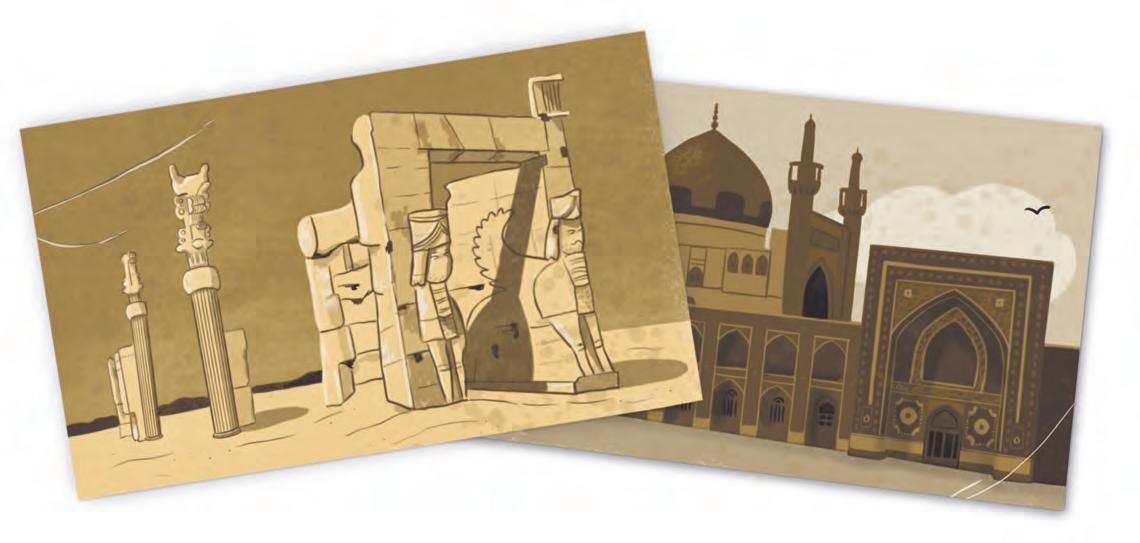

As second-generation immigrants go, I’ve mostly been isolated from my ‘home’ country. I don’t have dual citizenship, my language skills are largely confined to the level of family gossip and I’ve never even set foot in Iran. Instead, I’ve tended to experience my inherited culture through fragments and residues that keep me tentatively anchored to a place I have never been, but still feel intrinsically bound to: anecdotes and reminiscences from family, old photographs of Persepolis that my grandfather took in his student days, signs translated into Farsi in NHS waiting rooms. “That person is Iranian,” I exclaim triumphantly to friends who are a little nonplussed as to why I’m blurting out random facts about passersby. “Ottessa Moshfegh sounds like an Iranian name,” I say firmly, smug when I’m proven right. They’re very small things, but they are mostly what I have, keeping me moored to the culture in its broadest, most rhizomatic sense, fostering a minimal sense of belonging.

In this way, home – the ancestral idea of it – has become a kind of imagined place, experienced purely through second-hand construction. The connection I have with Iran feels tenuous, gossamer-thin and constantly on the brink of dissolution, yet, simultaneously, firm, undeniable and entrenched in my very identity. It’s a particularly second-generation experience – caught between belonging and not belonging – and one that is utterly bewildering in times of crisis such as these. When Trump threatened to destroy Iran’s cultural sites if the country dared to retaliate, it felt intolerably violent even though, at the time of writing this, it has remained a verbal threat. Disgusting as his proclamations typically are, these were personal and felt surreally, horrendously abusive. Of course, second-generation immigrants such as me, thousands of miles away from the physical land and – in my case – protected in a comfortable middle-class life, will suffer the least if military conflict unfolds. Yet we remain entangled with the place and its people, if only through the imagination, and the intimidation of such brutality is still unbearable. Carol Isaacs’ graphic novel The Wolf of Baghdad explores the exile of Iraqi Jews from Baghdad and lingers on the untranslatable Finnish word kaukokaipuu, meaning homesickness for a place you’ve never been. How I feel is a type of homesickness, but it is also more. It’s a compulsive and uncanny recognition despite almost no mutual experience or physical proximity. I am so far down the list of people affected by this potential violence and loss in their quotidian lives. But I still feel bound to it.

Of course, this impending sense of dread is not abated by historical perspective. There is a “It’s a particularly secondgeneration experience – caught between belonging and not belonging – and one that is utterly bewildering”

totality to Western violence in the Middle East that is sometimes too vast to comprehend. Estimates of casualties during the Iraq War vary from 100,000 to well over a million, while entire swathes of Syria have been razed to the ground. Millions of people have been displaced, many of them drowned in the Mediterranean as Europe frantically began to close its borders.

Although the response to Trump’s assassination of Soleimani was largely negative, it was frequently filtered through a fear of Iranian retribution and concern for American military lives. From both the political right and left, little attention was paid to Iran’s people, its infrastructure and the potential collapse of an entire cultural group. The West, as usual, conveniently forgot that the main victims of Soleimani and the brutal regime were Iranian citizens.

At the time of writing this, the mounting tension seems to have somewhat abated – at least on Twitter, a sentence almost too absurd to type – but new sanctions have been enforced, Iran is resuming its nuclear programme and there are demonstrations flooding the streets of the country. Iran still feels like it is teetering on an edge, caught in the push and pull of Western imperialist megalomania and the atrocities of its own autocratic regime, deeply vulnerable to both. And while my experience of the country has always been predominantly imaginary, the anxiety I feel is emphatically concrete. It’s the anxiety that second-generation immigrants know all too well, trapped in the liminal experience of attachment and exile, gazing across a gulf of continents, generations and familiarity, fearfully looking on.

— 41 — February 2020