7 minute read

Gifted and Talented System: A Gateway Towards Racial Division in Education

• Writer: Elenore Cornelie • Designer: David Kernan • Photographer: Elizabeth Redmond At Brookfield East and schools across the nation, there is a racial disparity in education particularly in AP classrooms. The gap is enforced through several factors, from social reasons to systematic issues. There are currently several efforts, both individually and through Brookfield East’s Equity Team to decrease the race gap in education.

A group of juniors at Brookfield East were discussing how they struggled to understand how anyone would graduate without an honors diploma (6 or more honors and AP classes). Jenny* (11), an African-American student sitting next to them, said, “I’m not graduating with honors. I’m only taking 2 APs,” said Jenny. “I’m not smart enough for that.”

Advertisement

Somewhere along the path of Jenny’s education, something convinced her that higher-level courses were not for her, and that same issue is why a major racial gap persists in AP classrooms.

According to the New York Times, “African-Americans, for example, represented just over 14.6 percent of the total high school graduating class last year, but made up less than 5 percent of the A.P. student population who earned a score of 3 or better on at least one exam.”

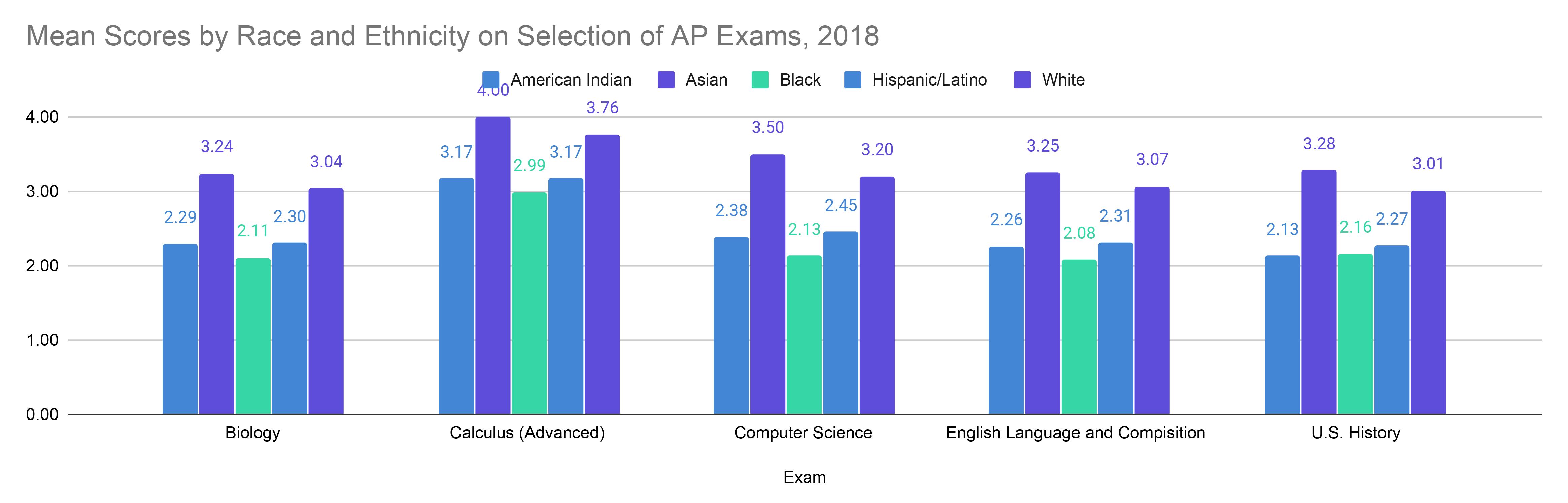

There is not only a racial gap in simply gaining access to AP classrooms but a gap between who succeeds in them.

Black students represent 8.8 percent of exam takers and 4.3 percent of exam takers who earned a 3 or higher on at least one exam. Hispanic/Latino students represent 25.5 percent of exam takers and 23.6 percent of exam takers who earned a 3 or higher on at least one exam. Brookfield East follows the national trend as black students represent 3.6% of the Brookfield East population and only 1% of all AP Exams. Hispanic/Latino students represent 5.7% of the Brookfield East population and 4% of all AP Exams.

Brookfield East has attempted to decrease the racial gap in education. The Equity Team has been working towards a solution for months. One of the bigger issues is overcoming stereotypes that exist in education today.

Jaden* is an Asian-American junior at Brookfield East. There are several stereotypes surrounding Asian-Americans regarding education. Among them include the “tiger mom” stereotype.

“It’s kind of annoying because I feel like everyone thinks I only do certain activities or take certain classes because my parents make me, and it’s really not like that,” said Jaden.

“I choose the classes I want to take.”

*Disclaimer: Jaden, Jenny, and Jackie are all names used for anonymity due to the personal information revealed through these interviews.

Brookfield East High School, 2019 It’s easy to assume the high rates of participation among Asian and White students are simply because of parental pressure, but that belief is more a stereotype.

The Equity Team, composed of Brookfield East staff and faculty, has recently been looking into racial disparities.

Many students and administrators place pressure on the students to succeed. They believe it’s the students’ responsibility to enroll in advanced classes and succeed. However, the educational system plays a big role in enabling the students into those classes. The school needs to offer opportunities and inclusive classrooms for all students.

“There’s a lot that the school and teachers can do to help make AP environments more inclusive for students. All students of all backgrounds,” said an Equity Team member.

Having taught AP classes for over 25 years, Mr. Patrick Coffey highlights the disparity but mentions it is beyond a racial gap, it is an economic gap. He notes many of his students come from higher socioeconomic statuses with stable family lives.

In CollegeBoard’s AP Report to the Nation, it noted that only 27.5% of AP Exam takers qualify for free or reduced lunch compared to the 48.1% of high schoolers in the United States.

Furthermore, less than 50% of 275,864 low-income public school students who took an AP exam passed their exam. Oftentimes, socioeconomic status is directly correlated with academic performance.

Jackie* is a Chapter 220 student who identifies as low-income. She says she wants to take honors and AP classes at some point throughout her high-school career, but she contemplates taking one because she works more than 30 hours a week.

“I know APs and honors have a lot of homework. I don’t get time for that. The bus takes like 45 minutes then I gotta get to work,” said Jackie.

Coffey also notices how underrepresented minorities are often outcasted in AP classrooms. The statistics also support this. At Brookfield East, the average Asian-American in an AP class takes around 3 AP courses a year and the average White AP student takes around 2.5 APs a year.

This suggests that most AP classrooms are composed of relatively the same students. For a student who does not have friends that are taking AP classes, it can be extremely difficult to take the jump and enroll in an AP or honors class. Students are naturally inclined to take the classes their friends are enrolled in.

But it’s not as simple as they’re only facing exclusion from their classmates, they may also get some ribbing from their friends.

“It was difficult socially because they’re taking a class that’s outside their comfort zone with all White/ Asian kids, and then they’re going to their friends who aren’t taking these classes [...] and they (the friends) would criticize these kids. They have to be exceptionally strong, to hold their own against their own friends,” said Coffey. That’s another one of the reasons holding Jackie back from Honors and AP courses. As underclassmen and juniors are scrambling to complete their schedules for next year, she often discusses potential classes with her friends. She says her friends often discourage her from taking AP and Honors courses in exchange for a study hall, or an “easy class.”

Furthermore, the racial gap in honors and AP classrooms is perpetuated by the Gifted and Talented system administered throughout the district’s middle and elementary schools. The Gifted and Talented program consists mostly of Caucasian and Asian-American students.

Granted, the title of being gifted and talented doesn’t really mean much but is a morale booster. It gives the students a sense of confidence in their academic abilities. In high school, this translates to an increased likelihood they will enroll in more rigorous classes as they are confident in their abilities to succeed in them.

“I definitely felt like I would be prepared for honors classes when entering high school because I had Honors Geometry in 8th grade, so I felt like if I could take a high school level honors class in middle school, I definitely could succeed in honors classes in high school,” said Jaden.

“I never thought I was stupid, but you know, there was a class of ultra-smart kids that I wasn’t part of, so I didn’t really think I was smart,” said Jaden when asked how she felt Gifted and Talented Program affected her course choices in high school.

“I thought I was average, so in high school, I didn’t sign up for those honors classes because those were the classes all the smart kids were taking and they’re way smarter than me.” Coffey added on.

It’s apparent the racial gap in honors and AP classrooms is not an issue that appears in high school but has been perpetuated and upheld all the way from kindergarten to where we are now.

Pre-AP classes are being added to middle school curriculum, and even Elmbrook’s elementary schools are segregated with 3 categories of math and various reading “levels.”

“The gap begins in elementary school. I don’t know if they still do it, but they have colors for different reading groups, but you know it’s for the smart kids- and that starts early on,” said Coffey. “And all of a sudden, you aren’t a smart kid. ‘Oh, I don’t want to take those classes, those are all the smart kids. I’m going to hang here with the regular kid.’ The gap is tough. Race has a lot to do with it. I would say it’s not entirely that, but it’s a lot.”

In CollegeBoard’s AP Report to the Nation in 2015, the racial disparities in education are widely shown. Only 1 state in the United States has closed the performance gap for African-Americans.

Collegeboard, 2013

As district administration talks about Elmbrook shifting to a minority-majority district within the next decade, the racial divide in AP classrooms will be an important issue to follow, if it’s even an issue as the district integrates.