6 minute read

Who owns the water from Lake Tahoe & Truckee River? Part I

BY MARK M c LAUGHLIN

Millions of people visit the Tahoe Sierra each year to enjoy and recreate on Lake Tahoe, Donner and Independence lakes, as well as the satellite reservoir system of Boca, Prosser and Stampede. All these storage basins are in California, but since the Truckee River system is part of Great Basin hydrology, none of the stream ow reaches the Paci c Ocean.

Advertisement

I frequently get queries, especially during a drought, regarding our regional water management. It seems that few people realize that these reservoirs, including Lake Tahoe, are regulated primarily for Nevada interests. Many are also unaware that a signi cant portion of this desert-bound water is dedicated to Fallon, Nev., one of the driest parts of the driest state. In that sunbaked landscape, water-intensive alfalfa is irrigated with Tahoe-sourced water to feed herds of dairy cows, with the bulk of the milk being dehydrated for export to China and Asia. is is the story of the Newlands Project, which turned water into gold for the Silver State.

It likely never occurred to indigenous peoples who inhabited the Tahoe Sierra for thousands of years to confront the natural uctuations of Lake Tahoe and the regional lakes. American Indians in the Great Basin survived by living within the natural cycles of the seasons, hunting and gathering in high-desert and alpine environments. Tribal people understood that winter rain and snow were inconsistent from year to year and they adapted to that.

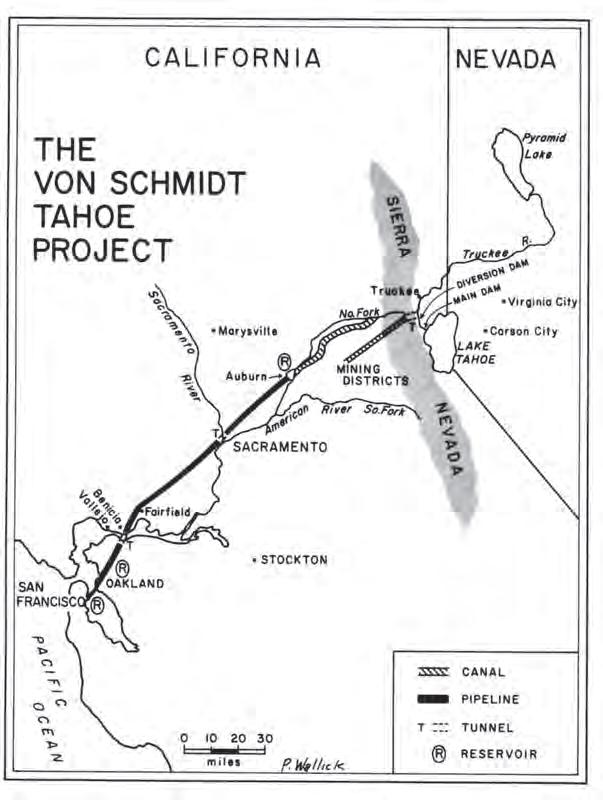

Topographical engineer John C. Frémont “discovered” Lake Tahoe in 1844 and within 15 years entrepreneurs were scheming to exploit its water. e most ambitious of these early diversion plans included transporting water to Carson City and Virginia City, Nev., or redirecting it to the gold diggings of Placer County or even San Francisco. ese mammoth public-works projects rarely gained su cient popular, political and economic support, but by the start of the 20th Century, Nevada had successfully tapped Lake Tahoe and the Truckee River as its primary sources for irrigation, industry and municipal water use.

travelers paying for a time-saving ride on one of Pray’s two schooners from the west side of the lake across to Glenbrook. From there it was a relatively short journey to Carson City or on to the Virginia City silver mines. Steamer piers at Glenbrook were built deep into the water as investors already knew to compensate for the wide variability in the seasonal surface levels of Lake Tahoe.

In 1865, a Prussian-born civil engineer named Col. Alexis von Schmidt formed the Lake Tahoe and San Francisco Water Works Company to supply water to the distant city via an aqueduct from Lake Tahoe. It was an audacious plan, but von Schmidt was con dent that he could build it. Surveys were undertaken to construct a canal from the lake’s outlet at Tahoe City to Olympic Valley, where a 24,172-footlong tunnel would be excavated through the Sierra Nevada to the North Fork of the American River. From there a series of canals, umes and pumping stations would transport the high-quality water to San Francisco.

Lake Tahoe has one outlet and it is the headwaters of the Truckee River in Tahoe City. Von Schmidt built a 50-foot-wide dam near the outlet to create water storage for his proposed Grand Aqueduct. “ e [dam’s] gates were suspended above the water, ready to drop at any moment,” wrote a Carson City reporter. Von Schmidt’s barrier did raise the level of the lake, but the overall project ran into resistance due to its cost, as well as erce local resistance, particularly by western Nevadans. Even so, in 1871 the Board of San Francisco supervisors approved the project, but the city’s mayor, concerned about legal suits over Tahoe water, vetoed the increasingly contentious proposal.

San Francisco still required reliable drinking water, however, and the source of choice became Hetch Hetchy Valley, 160 miles away in Yosemite National Park. It took years of political arm-bending and bureaucratic intrigue by politicians and businessmen, but in 1913 Congress

But as soon as Euro-American settlers moved in, the game was on to control the ebb and ow of Big Blue and the Truckee River watershed for economic gain: hydroelectric power, mills, ranching, agriculture and more. Whoever secured the rights to harness and distribute the liquid gold that water represents in the arid West would control the levers of industry, politics and development.

e rst permanent settlement in the Tahoe Basin was an industrial logging hub at Glenbrook, Nev., on the eastern shoreline. In the spring of 1860, four squatters settled the lakeside valley and built a log cabin. e men named their bucolic parcel for its babbling brook and mountain meadow landscape. In 1861, squatter Capt. Augustus W. Pray along with two new partners consolidated ownership of the land, formed the Lake Bigler Lumber Company and erected the rst sawmill at the lake.

During the early 1860s, Glenbrook became an important transit point with gold seekers and other

LEFT: Log drivers on the Truckee River. | Courtesy North Lake Tahoe Historical Society

BELOW: Von Schmidt’s plan to send Tahoe water to San Francisco. | Courtesy Donald F. Pisani, Tahoe Research Group

nally granted the city permission to build a dam in Yosemite. e controversial legislation infuriated environmental activist John Muir, who had led opposition to the project. In 1923, construction on the O’Shaughnessy Dam was completed and the valley that Muir described as “a grand landscape garden, one of Nature’s rarest and most precious mountain temples” transformed into a massive reservoir. e Lake Tahoe and Truckee River system dodged a bullet, but a combative water war between California and Nevada was just heating up.

Before a dam at Lake Tahoe converted it into a managed reservoir, water levels followed a natural rhythm. Each year, water volume was boosted by winter precipitation and then extended by snowmelt runo . Subsequently, the amount of water rushing down the Truckee River in spring was based on the previous winter’s snowpack and its water content. By the end of the summer, however, the surplus water drained out, at which point the lake reached its natural rim at the outlet and ow into the Truckee River e ectively stopped. But a reservoir with no storage is just a lake and the burgeoning development in the region demanded more. A dam to control water release from the Tahoe Basin was required.

In 1870 the California Legislature granted Donner Lumber and Boom Company a franchise to charge tolls for improving the Truckee River channel for oating timber downstream to Truckee sawmills. e out t was a subsidiary of the omnipotent Central Paci c Railroad. e narrow, shallow mouth of Lake Tahoe’s outlet is favorable for regulating water drainage from Big Blue into the Truckee River and Donner Lumber and Boom Company constructed a substantial dam to control ow for the log drivers. e legislation restricted the oodgates to a maximum height of only 5 feet, but due to Lake Tahoe’s size, the dam had the capacity to restrain a large volume of water. Read Part II in the next edition and at eTahoeWeekly.com.

Read more local history at TheTahoeWeekly.com

Tahoe historian Mark McLaughlin is a nationally published author and professional speaker. His award-winning books are available at local stores or at thestormking.com. You may reach him at mark@thestormking.com.