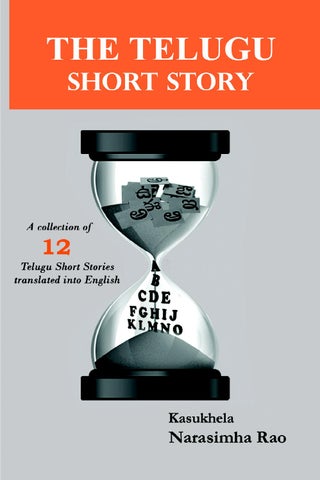

THE TELUGU SHORT STORY (A collection of 12 Telugu Short Stories translated into English)

Translation by :

KASUKHELA NARASIMHA RAO

"The Telugu Short Story" ( A collection of 12 Telugu Short Stories translated into English)

Translation by: KASUKHELA NARASIMHA RAO

February 2015

Published by : K.N. RAO

Price: Rs.100/-

Cover Design : T.M.Varunkumarni

Designer: G. Srinivas Supriya Graphics Chennai 600 024

PREFACE A centenary of Telugu short story had been celebrated recently. A gratifying fact of these celebrations has been that it received enormous attention at various levels -- State, District, and Town; Student writers, Woman writers and celebrity writers. However, there is a saddening side to this: not one had received PanIndia recognition, forget World recognition. Why, I asked myself. Came the answer that it was because translations into other Indian languages were scarce and scarcer still into English, a world language. The situation warrants remedial measures. This is an area where the Universities of the state have a big role to play. They have the manpower and the financial resources. I thought a small effort by me might act as a catalyst in this regard. It could be a stone hurled by a mad man: it might hit the target. I have no pretensions to any literary achievement. Yet my love for my Telugu, impelled me to place this ‘translations’ of 12 short stories which caught my eye put together. I’m no clairvoyant. If it serves the intended purpose, I can die happily: after all, I’m going onto 89. I’ll be failing in my duty if I do not acknowledge the enthusiastic support I received from: Sri M.A. Subhan Sri Vasundhara (Dr. J. R. Rao) Sri Kalipatnam Rama Rao Garu Sri M.L. Narasimham and last but not the least, Sri Ch. Madan Mohan Now, I wait and watch.

- K.N. Rao 15.1.2012

THE WHAT AND WHY OF THIS There is nothing in this world that is not worth a short story. No wonder, themes range all the way from the down-to-earth to fanciful flights of imagination. Naturally, every group of people, all across space and time, has its own garland of stories. The Teluguspeaking peoples living in their own heartland of Andhrapradesh and Telangana, as also its diaspora spread all over the world, produced their own spectrum of short stories, some recorded and some handed down through an oral tradition. In the last hundred odd years, the art flourished, indeed bloomed. However, there is an undercurrent of regret that the Telugu genius did not attract the attention of the rest of the world; many say, it is because the Telugu Short Story is not translated as much as it should have been. It must be admitted, albeit with some reservation, English is the global language of our time. So, a glimmer of pragmatism goaded me to translate some Telugu short stories into English, in the hope that this regret would be remedied, though perhaps only partly. The stories selected for translation has been a random exercise, culled out mostly from Kathasagar, a magnificent collection of Telugu short stories, edited by Sri M.A. Subhan of Kalasagar, a cultural organization that provided entertainment of first order to the Teluguspeaking people living in Madras (now, Chennai) and Kalipatnam Rama Rao Rachanalu published by Progressive publications and edited by Sri. V.V. N. Murthy and ‘Rachana’ Sai. ‘Aswamedhayagam’ by Sri Sri appealed to me as it talks of a day in the life of a man, thirsty for making a quick buck. The story appeared in the monthly magazine of ‘Swathi’, February 2012, under a feature titled ‘Naku Nachina Katha’-‘the story I like’. ‘Purugu’ by J. Ramalakshmi tells us of a housewife, very happy in the knowledge that her husband loves her to no end. ‘Galiveedununchi to Newyork daaka’ is chosen firstly because Rajaram had always been my favourite short story writer. It is about an irrational feud between two swollen – headed persons who are highly clannish from the countryside in Rayalaseema. ‘Tiladaanam’ is chosen as it exemplifies the profound knowledge of astronomy of our ancestors and also because it exposes the hypocritical life of the priestly class of our society. ‘Koolina Buruzu’ by Kethu Viswanatha Reddy is translated as it highlights the revengeful rivalry that prevails in the landed aristocracy of the Telugu Reddis. ‘Maro prapan chamlo Lakshmanarekha’ by Vasundhara focuses on the unassailable caste

consciousness along with the human side of the lady character, depicted here. Kalipatnam Rama Rao garu is a well-known Telugu short story writer. He has to his credit far better known stories than the ones translated here. But I wanted to capture the traits of curiosity and wonder of his younger days as well as his shrewd obersvation of a lazy laid-back life style of a person who totally surrenders himself to time and its abrasive action. Hence, ‘Emiti Idanta’ and ‘Nirvakalu’ written while he was still flowering into the well-known writer that he is today. ‘Kalanni Venakku Tippaboku’ by Smt. D. Kameswari is chosen as it features the struggle that goes on in a family caught between wanting to conform to traditional ways and a strong desire to go modern, all at once. ‘Dhakan’ by Mohamad Khadir Babu brings out the difficulty of being a Muslim in contemporary India. ‘Ma Nishada’ by Madan Mohan illustrates the all too commonly seen twist from which new opportunities emerge even as matters look wretchedly bleak. The last one, ‘Pullaiah Puranam’ is chosen primarily because it had been penned by the translator himself but secondarily also because of a unique experience of being spotted and patted by a group of his friends in a hotel in Nellore, his native town, where he went even as he was working as Assistant Professor of Botany at Pachaiyappa’s College, Madras (now Chennai). So, here is the vindication of my thesis, ‘There is nothing in this world that is not worth a short story’. Surely there are many more short stories in Telugu, worth the effort of translators. I translated these short stories in 2012, when I was 89. Now, I am 91. This humble effort of mine if it enthuses some younger translators, I’ll deem my effort has not gone in vain. As I said in the preface, the celebration of the centenary of Telugu short story in 2011 ignited the spark. May the flame spread and bring glory to Telugu Short Story. - K N RAO 22-1-2015. Address: K.N. RAO G2, Jains Akansha, 8. Rathinammal Street, Kodambakkam, Chennai- 600024. Phone: 044-24726617.

Inside.... ASWAMEDHA YAGAM

7

(EQUESTRIAN SACRIFICE) - SRI SRI INSECT

10

JONNALAGADDA RAMALAKSHMI GALIVEEDU TO NEW YORK - Madhurantakam Rajaram

15

A GIFT OF GINGELLY SEEDS - Rentala Nageswara Rao

27

THE CITADEL IN DISREPAIR -Kethu Viswantha Reddy

40

HER VERY OWN RUBICON -Vasundhara

48

WHAT IS ALL THIS? -Kalipatnam Ramarao

54

MANAGEMENT -Kalipatnam Ramarao

56

DONT TURN THE CLOCK BACK - D. Kameswari

65

THE COVER -Mohammed Khadir Babu

74

LETTER BOX - CH. MADAN MOHAN

85

MR. PULLAIAH’S RIGMAROLE - Kasukhela Narasimha Rao

89

1

ASWAMEDHA YAGAM

EQUESTRIAN SACRIFICE - SRI SRI

M

"

other serious start immediately" - read the telegram from Ramam. Venkateswarlu was stunned. His mind went blank. All thoughts froze. It was as if all his blood clotted up. No knife would restore its flow; if it did, it would be a deluge. The shock passed. A flood of thoughts surged through his mind. "Mother might die; he must catch the mail that evening. Wonder if she would hold her breath till he reached home. Why not tomorrow? Would her soul stay in that old frame till tomorrow? It is just not possible to catch the mail this evening. Why not tomorrow? Yes, I will go tomorrow. It is just not possible to catch the mail today. Why, why not tomorrow? And the money?� It is the racing season. His head is full of horses. This telegram would help him raise the money not from one source; several! A dying mother would melt even the stone-hearted. Four-five might remain unmoved. Even so, five-six others would relent. There is no doubt; he would be able to encash the telegram up to a hundred rupees, at the least. No time to waste. He dressed up. Literally penniless. Someone in the neighbourhood, who would give him a loan - who can it be? Who else? Sathyanarayana came to his mind. He lives just about four streets away, within walking distance. A type who would raise money, pledging his wife's jewels if necessary. Not very close to him, but close enough to tap for a loan, especially in a time like this. He called out: ‘Sathyanarayana garu.' "No he is not at home." Ill omen he felt. So early in the morning, where could he have gone? And then, he wondered if the telegram is on him or if he left it at home. He passed his hand over the pocket. He had the telegram, safe and sound. How to reach Sathyanarayana! May be, went to a hotel for a cup of coffee. A two anna coin is all he needed to go to a 7

hotel. And he did not have it. Let me see. His wife may know where he went. Why not? "Went to central station. I will tell him that you called", said Sathyanarayana's wife. Venkateswarlu knew Nair, the owner of the soda shop at the street corner. He borrowed a pavala from Nair. Boarded the bus. Did not feel like sitting. Travelled standing. All his thoughts were on horses at the race course, scheduled to partake in the races that day. He met Sathyanarayana, waiting for train's arrival. His brotherin-law was coming, said Sathyanarayana. Venkateswarlu found it not so easy to open the topic. "I went to your house. You were not at home. It is an urgent matter," was how he framed his opening remarks. No, a bad opening. He rubbed off the words, like a school boy would with an eraser. Without a word, he took out the telegram from his pocket and handed it over to Sathyanarayana. “Oh! What a pity!! Never knew your mother was sick." There was a ring of pain in Sathyanarayana's face. "Old age; what else? Is it not disease enough? I am planning to go by mail, this evening,” said Venkateswarlu. Venkateswarlu 's looks appeared as if they were shredding a vacuum that settled before his eyes. "I want to go. But I don't have a pie.” His words came out in so low a voice as if demanding an immediate response to help someone in great danger of getting drowned in a deep well. He took hold of the right hand of Sathyanarayana, pressed his thumb and right hand against his own forehead and said he needed twenty five rupees, the minimum requirement. “I need thirty rupees. Don't know how you would manage. But you have to give it. I don't have it in me to ask anyone else.” Sathyanarayana is a tender hearted person. It didn't take even five minutes for him to say that he would pledge some gold and give Venkateswarlu the thirty rupees he wanted at two, that afternoon. Venkateswarlu said he would meet Sathyanarayana in his office at 2 and take the money urgently needed.

* * * * *

It took all his skill to fleece ten rupees from Narahari.

* * * * *

Venkateswarlu reached Mylapore Bank in a taxi. He knew Kamesam, a chap working in that bank; not a friend but someone known. In such circumstances, acquaintances were far easier to handle than friends. Even after spending half an hour at the bank his collection had not grown even by a pie. He realized that in this stupid game, spending money on a taxi was idiotic and walked to 8

the homes of a couple of advocate friends. The telegram fetched Rs.20/ - at one place and Rs.25/- at another. The clock struck, twelve. He had Rs.75/- in his pocket. The horse racing was in full cry. With the thirty five rupees Sathyanarayana promised, he would have Rs.105/- And Guindy beckoned him. Last day of the season. Early next morning, he would board the Express. The previous evening he procured the pocket-sized book that listed the names and the provenance of the horses, their weight, handicap permitted, the owner of the horse and the jockey and such other details. He analysed the data, applying his mind with far greater diligence than ever before. Surely, you are going to hit the jackpot, shouted an inner voice, Why go home! Had small snacks at a wayside restaurant, went to Sathyanarayana 's office and from there to the Park station. Soon he found himself in an electric train, bound to Guindy. A Treble would yield seven or eight hundred. And he would hand back all the moneys he raised that very evening. His mind went on a journey into the past. Last month he bet all his month's earnings on horses, as recommended by others. What else, he lost all. Today, I'll do the betting on the strength of my own scientifically worked out database. Surely I am going to win. In fact there is no way I could lose. That evening, on his return journey from Guindy he had nine annas, two Wills cigarette packets, and the telegram he received that morning. His calculations were scientific, based on data he scanned. But those wretched horses did not know science!!! - Swati Monthly Feb 2012

9

2

INSECT - JONNALAGADDA RAMALAKSHMI

I

love the country, this country of ours. I like our traditions too. But some of those traditions irked me. No special reason. I am a woman .... That is the reason if you want to know. I stretch out my hands into the rain; I love it------- my hands getting wet. When I was quite young I used to do it. Mother would get annoyed .........her fear was that I would catch cold. But I would not give up. Many times I would get wet in the rain, when mother’s caring eyes were not watching me. And when reported, mother would scold me. "Did I fall sick!” I would counter. Mother had no answer. This went on till I was twelve. Now, she began singing a different song: "You are a girl.” “You better behave yourself—as befits a girl" she would say. Somehow that kind of control, I did not like. But now, all the others in the family joined the chorus. I did not know how to silence mother. When I turned sixteen, mother did not have to tell me that I was a girl. The way others looked at me said it all. The splash of rain drops as they hit me in the random way as they alone would used to tickle me to no end. It is my body; the way men began to look at it, made me feel bored through. For the only reason that I am a girl, I had to deny myself the pleasure of getting drenched in the rain. That is not all... And in summer, when it sweats and hot breeze takes your life out, my mother had to drape herself in a seven yard saree and tightly fit her chest in a jacket stitched from a mere 80 cms piece while my brother wore only his underwear and my father nonchalantly lifted his lungi up above the knees by folding it up above the knees and 10

moved around the house as if it is all so proper. For my part, I had to wear garments upon garments, of all hues and variety, just to hide what coming of age endowed me with. It was a humiliating discrimination. My anger at this knew no bounds. Further, when I see kids almost bare bodied, I regretted my having grown to sixteen. All this caused a hurtful pain that would tear through me. Yet, I am no advocate of rebellion. When my father found a husband for me, I never gave a thought to the problems he had to encounter such as raising money that would meet the demand for dowry. I had not thought much on the problems. On the other hand I went into a dream-state, a pleasurable one concentrating all my thoughts on the wonderful life that is opening out before me. Not for a moment, did I ask myself what made the male superior to female. I readily agreed to tag on his name to my own. That tag, I felt was the equivalent of a Ph.D.! I gave up the name of the family into which I was born and became part and parcel of my husband’s. Indeed he is my Mr. (though it is not an abbreviated form of master). He respected me. What is more, he loved me. He would always say to me, “yours is a thinking brain. Give it a chance. You'll grow into a dazzling diamond. If you have plans, you can depend on me. I'll be behind you!” “What do I need to accomplish?” I asked. "You may attempt to give a new direction to our traditional ways." If only one sits and ponder, the problems a woman faces in our society are nothing at all, quite in contrast to the security she enjoys. Our tradition and customs offer this double advantage. May be, some women face acute problems. As for me; I don't have any problems. Probably I'll know about them only if I experience them personally myself. I am quite happy as it is. When summer set in, my husband bought a unicool fan. The joy I spoke of getting wet standing in the rain I had it in a much greater measure than I ever hoped, for there was a shower bath at home. Come to think of it, if I have to stand in rain, the clothes I wear would stand between the splashing water drops and my body. Here there is no such screen. I love shower bath. As far as I am concerned, all the problems associated with being a woman vanished without a trace. My husband would say, "Your selfishness is closing out your intelligence". 11

He has a mindset that was extra fine, so fine that he would not kill a mosquito sucking his blood. If he were even to kill a living thing, he would imagine the agony it would go through before death finally puts a full stop to it all. The pests such as mosquitoes and cockroaches that infest our home are taken care of by me, me only. Sometimes, I would make fun of him, that he was afraid of those creatures. But he remains unmoved. If the creatures are too small he would stop me too to go on with my job. But then, I would tell him a white lie --- I am going to release them in the garden and go about as is my wont, throw them into the toilet and pull the chain. This is my mindset. And yet, why I did what I did today, I do not know. I grew narcissistic. My skin was aglow in a golden hue. I felt like kissing myself. The shower was on. The water drops sliding down my body appeared like so many pearls leading me on, into some other world. The Jasmine soap I held smelt heavenly and I slipped into a dream like state. Then... I saw a small dark insect. It is quite familiar though I did not know by what name it is called. Dark and half an inch long it had a cuticular coat. If the occasion demanded, it could fly two or three inches off its substratum. Many a time I killed that insect in my own way, push it into the toilet and pull the chain. The one that caught my eye then was the very same insect, no doubt. The water from the shower flowed down into drain via my body. I saw it caught in that stream. It was trying hard not to be swept away. A good part of its body was under water and disabled it from flying. The water stream was too rapid. On an impulse, I closed the shower. The flow of the stream slowed. The insect is now able to swim against the current. I looked around. I saw the wrapper that I undid from the soap before I got under the shower. I took out the wrapper and placed it in the insect's pathway. It found a way out from the death trap, by managing to crawl on to the wrapper. I lifted the paper with the insect upon it and put it in a corner, quite out of the way of water stream. The insect is in a safe spot. All the time I was bathing, my eyes remained on the insect. I was extra careful and engaged myself over watching the insect and its safety from the water stream. I was surprised at myself; the why of this extra care I am lavishing on an insect which on many occasions earlier I consigned to the toilet and the gushing waters eluded me. 12

I came out of the bathroom and gave a detailed account of what happened in the bathroom to my husband and as an after thought, recalled the popular saying, "Six months of togetherness makes one the other" and said the adage appeared to have come true in our case. A smile danced on his face. He said, "Nothing of the kind. Did you write to your mother?" He took care to see that his tone did not betray any other feeling than that of a casual enquiry. "No. Not yet", I said. Don't know why but a shudder passed through me. My mother's birth place was Dhavaleswaram. She went there with her father and two uncles of mine. I know Dhavaleswaram was in the grip of floods. Mother, her father and my uncles were getting carried away and luckily for all, they reached a place where they found safety. Caught unawares, none of them had a chance of survival. One of my uncles knew how to swim but not enough of the art to save the rest. God in human form, a Good Samaritan, a total stranger saved them. He helped them go up the steps leading to the temple of Janardhana swami. Mother was in a terrible shock. She spent a whole night on the hillock. All around, the river was flowing in all its fury. She had lost all hopes of coming out alive from the ordeal. And now, she wrote to me. She said, the roads are too damaged and are not fit to travel; and that I better drop my plans to go to her place. Mother's letter impacted me a great lot. Possibly, the way I reacted to the possibility of an insect getting washed away was, if I may say so, telepathic. Otherwise how do I explain the concern I felt over the fate of an insect? His sensibility would not let my husband go to the matter straight, making me unhappy. The letter that I planned to write to my mother came in handy to break the news. "You are capable of deep thinking. Hone it and you would be a diamond and grow into a beacon light to the world of women. You can always count on me. Let not selfishness blunt your intelligence", he said for the umpteenth time. The floods and the news about it did not stir me a whit, until I heard about the ordeal my mother went through, on account of the floods. News items, quite heart-rending were aplenty. But none moved me. I knew that the township where father lived was not 13

affected by floods but little did I know that mother planned to go to Dhavaleswaram. Fellowmen, indeed my very own Telugu speaking folk went through untold suffering because of the floods. I was not touched. But, when my mother was affected by the very same floods, something impacted me and made me go to the aid of an insect, caught in a similar plight. "An intelligent mind capable of deep thinking: let not selfishness swallow it"....... The words began to ring loud in my ears. The words seem to possess an element of truth in them. I must begin a new life. Live not for self alone, assign some time for others. So many events take place every day. If only we keep our eyes and ears open, there are lessons to be learnt. But many of us choose to live in a world of our own, unmindful of what is happening around us. I went into the bathroom and looked at that insect again - the one which I saved from getting drowned. But now it does not look like an insect; in it, I see my servant maid, the beggar who stations himself near my house, the children from the orphanage going on a fortnightly march singing songs seeking help, the five year olds struggling to carry loads many times heavier than themselves --- so many scenes passed through my mind. Man was an insect before the fury of Godavari floods. The insect in my bathroom made me into a humane human being. - Andhra jyothi weekly – 11.9.1987

14

3

GALIVEEDU TO NEW YORK - Madhurantakam Rajaram

I

t was all so unexpected: as if a dream come true. True, every time his nephew, Madhusudana Reddy came home to India, he would urge his uncle, Malla Reddy, to go to America. “Don’t you worry, mama. I’ll make it very comfortable for you. I’ll spare no effort to make you feel the visit was worthwhile,” he would say. But little did Malla Reddy expect that his travel plans were drawn up to a T. It was all done without his having nodded his approval. Not that he ever wished not to go abroad. But his arch enemy, Chenchu Rama Naidu, was always a thorn in his flesh. That is the rub. And yet, Malla Reddy was not above blame. No deluge, no thunder bolt would deter him from doing whatever he wanted. Who else could have handled the party politics of the village as well as he! For ten long years! All disputes stem from a tiny spark. So did the rivalry between him and Naidu. A small sprinkle to begin with, it grew into a storm fanned by elections to the Assembly. Naidu was the opposition candidate. Reddy won. But he had to step down because of an election petition, citing irregularities from electioneering, voting at poll booths and counting votes. The petition highlighted every single malpractice, magnifying each a hundred fold. The court decided that Reddy vacate the hard won seat. That day, Reddy swore: “Aye, Chechu Rama, I would not be true to my name if I did not play football with your skull on the dry bed of our village tank.” The vow would stay valid until Naidu’s head was severed from his torso. As if it was a prelude to the shape of things to come, the lime trees – all the four hundred of them – in Naidu’s orchard stood truncated. “Reddy resorted to rigging and I lost the election by a margin of five thousand votes. And now equal to its weight in gold, the lime 15

trees in my orchard stand truncated. How can I sleep until that Reddy died a dog’s death,” swore Naidu. Though apparently Malla Reddy was not shaken, he secured the services of four goondas to act as his bodyguards. Five years ago, Naidu struck a deal: he bought a mango orchard, ten acres in extent, far away from the village at the foot of a hillock. The deal was struck on the strength of a word of honour. Happy at the deal, he was getting dressed up to go to the Registrar’s office. And comes the news: Reddy forestalled him. Not a word reached Naidu’s ears, until it was too late. Reddy’s triumph was short-lived. Yes the deal had legal sanction but the fruit of the deal eluded his grasp. The orchard was too far away. So, he built a living quarter in the garden and engaged a yanadi family to keep watch. Hardly the watchman’s family settled down, one night some masked men raided the orchard, beat up Subbadu and his family black and blue. The watchman and his family fled without leaving a trace of their whereabouts. It remained an orchard in name only. All called it a mango garden: trees without branches, not to say fruits. The trees were cut into small pieces and Reddy did not have a log worth a dime. Fencing did not improve matters. The muslim traders who buy the rights for the usufructs of the garden -- not one turned up. Malla Reddy clenched his fists, gnashed his teeth and literally emitted fire from his eyes every time the mango garden came to his mind. He sweated heavily and that was that. If Naidu smells of Reddy’s plans to go to America, he would do everything in his power and see that the plans failed. He might influence police and cause them not to issue a N.O.C. Reddy took every care to keep his plans secret. He obtained police clearance and passport easily enough. But there could be a problem over getting the visa. The lady officer at the Andhra counter looked at Reddy hawk- eyed. His hair style, thick mustache, eagle eyed look, the gold bordered garment around the waist and the long upper garment draped around the neck falling down on either side of his body up to knees looking as if it is a garland of flowers --- no, he did not look like one on his way to America. He looked more like a local satrap going to a wedding at a princely home, or someone on his way to a cattle fair to buy high breed bulls. “Mr. Reddy, what prompts you to go to our land?” asked the American lady, in chaste Telugu with a Sanskrit accent. “Why do you go to America? My nephew is in Chicago. And Jagga Reddy, my sister-in-law’s son lives in Detroit working on, what do you call them, ah! Yes, computers. And another boy of my clan, he is in Dallas 16

running a silk emporium earning dollars in millions. And what do you call that town, Austin or Houston... “Enough, enough, Mr.Reddy. Incidentally who is buying the ticket – you or one of them in U.S.A.?” Appeared stung to the quick, Reddy pulled out a pass-book from his pocket, pushed it through the counter and said, “This passbook is from the SBI. And I have accounts in two other banks too. And several fixed deposits.” “Right, Mr. Reddy. I don’t need to see your books. I am issuing a visa to you. You can stay there for six months. You may travel all over U.S.A. leisurely. May your journey be attended by happiness and profit, come back safe.” She sounded apologetic. Six months! Chenchu Rama Naidu came to his mind. “If I am away for six months sightseeing in America, who will check Naidu’s tantrums? Would there not be a crop of mustache on his elbows? My men, would they have to stay without protection? Who would counter the sword he would unsheathe, knowing that he is not around? Would it not amount to surrendering the fort to the enemy? Was he one to sneak out through the back door?” All these remained unspoken thoughts. Midnight, the flight took off at one’o clock. Seated next to him was a Tamilian. Much against his natural inclination, he had to stay silent. At Delhi, all the passengers disembarked. Nearly two hours later, he was led into another plane. Seated next to him was a thirty year old youngster. The forced reticence was growing unbearable. He must find out what language the boy spoke. Malla Reddy was at school for some time in his younger days and so was not altogether unfamiliar with English. He decided to break the ice and said, “Which place... you coming?” The boy broke into a smile and said, “I speak Telugu. A native of a village near Kalakada, Chittoor district. I did Engineering and am working in a construction firm, near Pittsburgh.” Reddy’s mind began to work. Good, but I must know if this boy is of my clan or not. Otherwise, when the time to share food comes, how will I decide if we eat from the same plate or he from a leaf and I from my metal plate. “But how... No, a direct question on the subject would not do. Ok. Let me get to the point from another angle.” So he asked him? “What is your name, my boy?” “Gopalakrishnamurthy. You may call me Murthy” replied the boy. ‘Umm! This bird in its golden cage has to come out and reveal itself in its true colours. My bait had not been good enough. I need to plan my enquiry far more meticulously. He cannot but let me know 17

his clan,’ thought Reddy. A plan unfolded itself in his mind. He jumped into the fray and said, “My village is not far off, Galiveedu near Royachoti. I know your region quite well. I used to visit those parts, for buying cattle. Kalakada, Gurramkonda, Mahalu – I know the area like the back of my hand. It is a war zone. Fierce battles rage between Kondapuram reddys and Pothugunta naidus. How is the situation, now?” “Let us not talk about it. Thanks to these warring clans, twenty to thirty villages in the region do not eat or sleep in peace. A bus plying in the area was stopped, a passenger was spotted, dragged out of the bus and was stabbed to death by a gang of four or five, obviously of the opposite camp. The victim’s wife swore that she would not change into a widow’s garments until her husband’s killers were killed. Frustrated that the killers escaped, the victim’s men set fire to their homes, burnt their haystacks and had sumptuous dinner where the main dish was the meat from their slaughtered sheep. Ten days later, the leader of that gang was killed at Madanapalle bus stand in broad day light, even as a crowd of four hundred was present there. The fire is raging. Nobody seems to mind it. In fact, dozens and dozens of ghee tins is poured over the flames, just to stoke the fire. Where and when will it all end?” “No, no. I know it all. But who has the upper hand?” asked Reddy. This question sent Murthy into a flying rage. He burst out, “A knife is used to cut throats. What does it matter whose it is, whether yours or mine. Who is the nice guy asked some one of a father. ‘See there, the fellow standing atop there swinging that firebrand, he is the best,’ said the father: so goes a folk tale. That is the answer to your question. Do you know why I am going back within two weeks of coming here? I came to see my mother. She is grief- stricken and bed ridden. She is grieving over the death of my younger brother. Absolutely not connected with either of these parties and yet, he was killed. You know why! only because from behind he looked like the son of a party leader. There was a group waiting for the prince to appear. It was dusk time. My brother went to Kondapuram on some business. He was on his way back home. The killers mistook my brother for the Yuvraj and hacked him to pieces. The body was not traced: only pieces of organs. And a gunny bag containing the cutpieces was brought to my mother. Its mouth was tied up. ‘Here is your son,’ they told my mother and left. Malla Reddy was dumbstruck. He wished he did not talk at all. “As I was getting back, you know what my mother said to me?” “What did she say?” asked Reddy. 18

The boy’s voice sounded heavy. “My dear son, don’t you ever come back to this country of ours. Settle down in that foreign country. Please speak to me once every week over the phone. I’ll have my peace of mind, even if I can’t see you in flesh and blood.” As if to regain his composure, Murthy took out a book from his bag. He got immersed in reading and soon slipped into deep sleep. The crew drew curtains and switched off the lights. It was like night time. Malla Reddy seemed to have forgotten his Galiveedu, forgotten the city he was going to, forgotten his enemies, forgotten his rivalry, forgotten his vengefulness, forgotten the police stations and the cases pending in the courts and eased into a slumber, totally oblivious of the discomfort his body was subjected to. Around 4’ O clock in the evening, the plane landed in the London Airport. The passengers were guided into a lounge where they could comfortably sit through the two / three hours needed for the staff to freshen up and refuel the plane. Once more the plane got airborne. It was daytime all through. It didn’t look like night coming. There is no date change too, he was told. Malla Reddy felt he was getting towed into an unreal world. New York was only few minutes away. A kind of fear, bordering on nervousness crept through him. A new, alien country. The smattering knowledge of English, no more than an incoherent assemblage of words he was familiar with, did not give Malla Reddy the confidence he wanted for the Whiteman’s way of speaking it was beyond his ability to make anything out of it. For now, the success of his trip to America depended upon one, Chintala Ravindra Reddy. He was to meet this Ravindra Reddy. If by chance, he was not there, what then? Who does he contact and where would he go? Chintala Ravindra Reddy is a friend of his nephew, Madhusudana Reddy. The snag is Ravindra Reddy lived in New York and Madhusudana Reddy lived in Chicago. It might not be possible to arrange for his halt at New York while he was on his return trip. And so, it was arranged that he would spend a week in New York, in Ravindra Reddy’s home. See all that there is to be seen at New York and then, move to Chicago, to his nephew’s home. Madhusudan arranged it all. But he had not seen this Ravindra Reddy nor Ravindra Reddy saw him. How are they going to place one another? Oh! How is he going to surmount all these tricky situations! He hoped Murthy might help him out. But it was not going to happen that way. Murthy told him that he has just half-an-hour to catch his flight to Pittsburg. May be, he can be of some help till after Mr.Malla Reddy collected his luggage. Thereafter, Reddy has to be on his own. 19

The Airport was blindingly bright. Can there be another place like this in the world, was the thought that crossed Reddy’s mind: it is a wonder created by modern architectural science that is John F. Kennedy International airport. It symbolised American prosperity, glory and capability to build wonders, not found elsewhere in the world. And the crowd, all the time on the move in spite of its numbers; shops, hotels, telephone booths and a variety of other types of services. Centers separated by crescent shaped pathways and half moon like walls, rising all the way from the floor to the roof and the roof itself fitted with translucent glass reflecting all that found on the floor – making it all look like a man-made ocean. He felt like a drop in the ocean with no separate identity of its own. Who is he, wondered Malla Reddy. May be, they built this megacity here to make individuals who throng there lose their identity. Suddenly, he felt he was not Malla Reddy from Galiveedu but a nameless person, without an address of his own. And Murthy helped him collect his luggage and went his way. An indescribable loneliness engulfed him. In that ocean where men of different races, different countries, speaking different languages, each differently dressed, of different ages, young, old and middle aged, he was getting tossed around, looking eagerly and keenly into every face that faintly looked Indian – and yet inexorably moving towards the exit gate. As he was thus lost, lost even to himself, he heard a voice that came like a shower of rain on a piece of badly parched land. The voice had the fragrance of rose-water. “Hello! Namaskaram. You are Malla Reddy garu. Am I right? Give that suit case; I’ll hold it for you.” “How did you recognise me, young man,” he asked in a tone of surprise and wonderment. “Madhusudan wrote to me. He gave me all marks of identification. But above all, the sentence he reserved to end his letter helped me a great deal. Shall I tell you what he said there? He wrote to say “if you find any one in that John F. Kennedy International Stadium who would look like RaRaju, Duryodhana, in the Maya Sabha, that would be my Malla Reddy mama. And you looked exactly that.” “Oh! That’s it; that’s it.” He tried to wet his dried up lips with his tongue and finally succeeded to smother his amazement with a loud guffaw. Soon, they were outside the main gate. Malla Reddy asked Ravindra, “How do we go home from here? How far is your place?” “My home is not far off. Just seventy five miles and an hour’s drive. My car is in the workshop; small mechanical problem. I have 20

a second car but my wife took it to the school to drive our son, back home. So, on a request from me, a friend brought me here in his car. He did not find a place to park the car. So, he went on rounds in the nearby roads. He’ll be here any moment. Please be seated in that chair, there.” The car came in about ten minutes. The luggage was loaded in the dicky at the rear of the car. Malla Reddy settled down in the back seat along with Ravindra Reddy. The friend at the wheel looked at Malla Reddy and said, “Namaskaram. Ravi told me about you. It is a great pleasure that elderly people like you come here once in a way. Surely, we’ll learn a great deal from you.” “Oh! I forgot, I hadn’t introduced to you my friend. He is a native of Singanamala near Anantapur. He is working in a University near here, now for ten years. His name is R.N.Tummala. You may call him Mr. Thummala.” “Thummala! What kind of name is it?” said Malla Reddy in a tone of amazement. “That is how it is here; his full name is Thummala Ramachandra Naidu. It got metamorphosed to R.N.Thummala. Same is my story too. No one would know me if you ask for Chintala Ravindra Reddy. I am known to all as R.R.Chintala.” “But, why?” “We decided to do away with flagging ourselves by our clan / caste names. As a first step, the suffix indicative of the clan / caste to which we belong is rubbed off.” “What do you get out of this?” asked Malla Reddy. “You must have noticed. At the airport, there were Whites, Negroes, Muslims from the east, Buddhists from S.E. Asia, Indians and many others. All of them, all forgot the land of their origin and settled down here. After all, all countries in the world are part of the same creation. No one country can claim the exclusive right of belonging to the world. This emigration, a feature of modern times, made all countries into a single mass, at least conceptually. Though as yet, religions and religious identity had not disappeared, we’re hoping that by the time our children grow up, the barriers standing between the citizens of different countries, races, languages would crumble and lead to friendship and even marriage between groups. As a concept, it has a potential to bend and break the mountainous barriers that separate one man from another. When that happens, the clan and caste consciousness would disappear. Man would then outgrow national identity giving way for a universal brotherhood. The identity that a country, language, religion and caste give would 21

become anachronistic. Justice, generosity, genteel helpful quality, love and tolerance and such other qualities would be the hallmarks of that new man. That is what we believe in. Every man must primarily be human: that is our goal.” “What! Is this a new religion?” asked Malla Reddy in a tone tinged with ridicule. “No, not at all. The idea had not come from us. Gurajada visualised an ideal world in which all nations lived in amity and friendship, between which no racial distinctions exist and a single lamp of wisdom lights up all humanity in its entirety. He visualised that such an order would emerge in the next century. Why should we not work towards that kind of world, a dream that would become a reality at least in the next century?” Malla Reddy did not know how to respond to that new hope and dream of Ravindra. But he understood one thing. These boys had no use for terrorism and stories of vengeance. They did not have ears for such things. Bomb bursts, murders in broad day light, rivers of blood, setting fire to homes and such other actions do not seem to drive them to action. And what do they want to know from him? He had his answer that night, after dinner. Ravindra and his wife raised questions on a huge range of topics. The NRIs are funding programmes aimed at obliterating illiteracy, improvement of living conditions in the backward regions of India. Are these projects moving in the right direction? How much are the social welfare programmes of Sri Satya Sai Baba trust helping the needy? Have you heard of Baba Ampte? What can you tell us about the selfless work he is performing? Mother Theresa is eulogised as an angel in human form. Do you think she deserved all this praise? Do you know of anyone who is as great as Mahatma Gandhi in contemporary India? Malla Reddy did not know answers to a great many of these questions. He felt like a total illiterate; like someone not even knowing the alphabet asked to read and explain Mahabharata? He chose to stay silent, just listening. The seven days he was in New York were like seven seconds. Ravindra’s wife addressed him, Babayi and this conferred on him the status of an uncle. She would take out the car at nine in the morning, drop the son at the school and take Malla Reddy sight seeing. Sky scrapers, underground trains and shopping malls -- she took him everywhere. She helped him buy all the trinkets he fancied. She took him to Chinese and Italian restaurants and showed him what that food would taste like. Lunch was always at an Indian restaurant and he did not miss Andhra cuisine in New York. Post-lunch, they would 22

spend in the green lawns on the banks of River Hudson and he would be all ears to her narration of life in America. Malla Reddy would wake up at six in the morning. As he finished his morning ablutions, the litre of drinking water with which he would begin his day’s activities, would be ready. At six-thirty, he has his coffee laced with a small quantity of sugar. For an hour afterwards, he would go on his constitutional. On return, a very refreshing bath and then breakfast: if it is idly, six: if dosai, three served with sambar or chutney but always dry chilli powder made into a semi paste mixed with ghee. If at home, at one’ o clock lunch was ready. Ridge gourd, okra are his favourite vegetables: bitter gourd and eggs are taboo. But chicken biriyani and mutton koorma are his favourite dishes. Green chillies are his passion. And every dish had a distinct, sharp taste, very much the way he liked. Ravindra’s wife did not take long to know his likes and dislikes. He did not have to tell her what he wanted. “Son, Ravi. God gave you a great gift. That gift is your wife. I don’t know who her mother is but I have to say this; blessed is the mother who bore Neeraja. My child Neeraja, your home is blessed because of you. It is a treasure house where nothing is wanting. And yet, this Malla Reddy wants to give you some thing. What can he give you? Ask, ask unhesitatingly.” “There is one thing which you and you alone can give, Babayi. I wouldn’t ask for it now. I would ask for it on the eve of your departure from this home, that is now yours as well,” said Neeraja. “Uncle, do be careful before you promise,” intervened Ravindra. “You do not know my Neeraja as well as I do. I warn you. Don’t blame me later. Neeraja can pulverize mountains into hills. I asked her to tell you all about her without hiding anything. And what is she doing? She is letting time to go by without making a clean breast of everything.” “What Ravi, what are you trying to say! I think you are raving, speaking incoherently.” “A little while ago did you not say blessed is her mother. The truth, when you come to know it would make the ground on which you are standing cave in. What does it matter who her mother is: perhaps it doesn’t. One has to have a mother but I am sure she would not have told you who her father is. Hear me. His name is Kommineni Sri Ramulu Chowdary, a native of a small village near Narsaraopet. Neeraja’s brother and I were classmates at the Engineering College in Kakinada. Naturally, I visited their home, more than once – in fact many times. This girl, Neeraja, lost her heart to me and I lost mine to her. And we married. Believe me, no 23

comets appeared in the sky: no meteorite showers nor did it rain fire. Clearly, therefore, there was no transgression of Dharma.” “What are you telling me Ravi! Is Neeraja of Naidu stock?” asked Malla Reddy. Clearly, there was disbelief and consternation in his voice. “That is not all. If I tell you another secret, you might jump as if a bomb had burst near your feet. Neeraja’s sister, the younger one is married into a home in your district.” “What! In my district! Where? The village name?” “Pankajam, Neeraja’s younger sister is married to the son of Chenchu Rama Naidu of Mittupalem.” Malla Reddy had a choked feeling in his throat: as if a good sized woodapple got stuck there, too large to swallow and too small to spit out. Totally flummoxed, he fell silent. Minutes ticked and hours fled, in total silence. It was the day of his departure for Chicago. Ravindra said he would come home early, at 5’ evening. Ravi and Neeraja would see him off at the airport. The flight was at seven, that evening. After lunch, he had a catnap, caught his forty winks. He heard footsteps. On opening his eyes, he saw Neeraja entering his room. She had a jug of water in her hands. Never before through all the days he stayed with them, Neeraja sat in the room where he rested. But now, she drew a chair and sat down. “You promised a boon, remember? I thought you would yourself broach the subject. Are you angry with me?” Neeraja asked. “How could I ever be angry with you? No, on the other hand, I was thinking of having a long chat with you on the subject. We led our lives most irrationally. Though young, you opened a new window to me. Your words and deeds have left a deep impress on me. I have two daughters. That was before I came here. Now, I have three: You are the third. Please do ask whatever you want to. It could be a monkey, from a troupe that lives on the hill outside our village. It will be with you, coming as it would in a cargo flight. The promised word came from my tongue, not from the bark of a palmyrah palm.” “No, Babayi. Please do not feel I am binding you fast to the promise you made. You are free to forget it. Please do not feel bad.” “No big deal. Go ahead and ask.” Neeraja sat with her eyes fixed on the ground. There was a gurgling sound in her throat. Yet, no word came out of her, she stayed silent. “Why child, go on. Ask of me whatever it is you want,” said Malla Reddy. 24

“Well Babayi, please do ponder over what I am going to say and try to be positive. You heard of the old adage: a fight always ends in losses while friendship yields goodwill and gain to all the parties concerned. Would it not be nice if you put an end to all animosities and let friendship bloom?” “I really do not quite understand what you are driving at.” “Do you subscribe to the idea that effacing enmity is better than vanquishing an enemy.” “Please Neeraja, do be a little less vague. Come to the point,” said Malla Reddy. “Every week I and my sister, Pankajam daughter-in-law of Chenchu Rama Naidu garu speak to each other for over fifteen minutes. Every time, she tells me she has no enthusiasm for life. Always, she cries and agonises. She complains about a fear, gnawing at her vitals and causing a fear psychosis because she always senses some bad news. Life, she says, is like a battle field always expecting a sharp hit from a sword or gun shot from the most unexpected quarter at an unexpected moment. Heads chopped off like they do a gourd from its stalk, ground drenched in blood, families of the fallen crying their hearts out. How long, how long can we keep our peace of mind and find a few happy moments? I love Rayalaseema. The terrain is such that a low rainfall, just about 100 mm every year, is enough to fill tanks and yield crops plentifully in quantities sufficient not only to satisfy their hunger but even sell some surplus and have some extra cash on hand. If only a change of hearts occurs in two, there can be no village in the whole world, happier to live in. But these two don’t change and there is unhappiness and constant fear ruling our lives. This is the refrain, week after, week after week. Babayi may I request you to let bygones be bygones. Let there be peace and harmony between your families. Would you rewrite the story in Mittapalem?” Malla Reddy was lost in thought for around fifteen minutes. Neeraja was shaking. And finally, he said, “But the initiative for change should come from that end.” Neeraja’s face lighted up. She said, “Babayi, now I have to perform a duty, assigned to me by God himself as it were.” She made a long distance call. When the call went through, she said, “Hello, Mamayya garu, I am Neeraja speaking. “Our long confabulations these past three days seem to bear fruit. Matters headed to a climax, just now. Malla Reddy Babayi is here with me. You may speak to him”; so saying she handed the phone to Malla Reddy. “Yes Naidu. Oh! Good, good. Doesn’t it strike as wondrous that a young girl served as the instrument for this turn of events? The 25

credit is hers. As for me, I feel silly. What could have been settled in your lime garden, in a highly agreeable odoriferous atmosphere or in the mango garden over platefuls Malugova pieces is now settled, with me in America and you in Mittapalem. Let us put aside our spears and swords. Yes, we should have seen the point, long long ago. Let there be prosperity and happiness for all of us. We’ve had enough of bad blood between us for ten years. Let it all be behind us from now.” “I’ll be back in two – three months. You prepare the ground for peace between us. Your terms are my terms. Please tell Neeraja, the good news,” said Malla Reddy and handed back the phone to Neeraja. Andhraprabha – weekly – 19th Jan. 1998

26

4

A GIFT OF GINGELLY SEEDS - Rentala Nageswara Rao

B

hagyanagaram is fast asleep. It was a slumber of exhaustion, like that of a mother, heartbroken at the way her sons readily slaughtered one another, all over a petty property dispute. Musi symbolised the streaks left by the flow of her tears. The clock struck two. A 34-year old man warily moved through the shadows carpeting the Chaderghat Bridge. His head carried a price tag of Rs.50,000/. Notwithstanding the neon lights fitted there, thanks to the commission which got secreted in the depths of a minister’s pocket, the place remained dark. The soiled clothes the pedestrian wore made the place darker still. The man had stubble on the face. He wore pajamas, a round-necked collarless full-sleeved jubba. His eyes were deep, sunken and he had a pistol tucked away unnoticeably somewhere on him. Dead or alive, whoever handed him over to the police would be richer by Rs. 50,000/-. The man was headed towards Isamia bazar. Isamia bazar, no it is not a muslim area. In fact, Brahmins who make a living as chaplains lived there. The man walked stealthily through the bylanes of the area and knocked on the doors of a small tiled house. Even as he did so, he looked around. A feeble voice, clearly tired, made even more so by a persistent cough, called out from inside the house, “Who is it?” “It is me, Raghuram,” said the man in almost an inaudible whisper. The cot creaked, as a man lifted himself out of it. Supported by a staff, the man walked to the door with great difficulty. The door opened, just a bit. Even so, it made a protesting sound. 27

Raghuram looked at his father. The halo around the old face, the shiny scalp with hair locks falling randomly over the nape of his neck, the broad forehead sporting the half-erased lines of Vibhuti, the garland of the tubercled Rudrakshas (Elaeocarpus), the dhoti from which all shine had disappeared, the eyes totally innocent of malice, the jaws hanging loose, the beard gone white with sorrow and cheeks sunken deep --- the dusky light from the bed lamp in the room showed it all. Tears swelled up in Raghuram’s eyes. Shading his eyes with his left hand, the old man asked, “Who?” Once upon a time, this man was Subrahmanya Sastri, conversant with Vedic knowledge: but now, he is Subbaiah, the brahmin all too ready to accept a gift of sesame seeds – gingelly seeds – just so that the giver and his family would be spared the malevolent influence of Sani – the planet of Saturn. Raghuram pushed open the door, walked in, closed the door and said, “Father, it is me, Raghuram.” “Oh! It is you, who shed every vestige of oriental culture! Why did you come? You will not allow this old man to die in peace,” said the father and virtually sank back into the old cot. “Has Padma given birth to a child?” Raghuram asked in a tremulous voice. “Aye. It is a boy. Moola star. A great propitiatory pooja which alone would vouchsafe everyone’s safety needs to be performed,” said the father. Raghuram parted the bed sheet that ensured the privacy of mother and baby. He saw Padma lying on the bare floor. His wife. She was asleep, with the baby suckling at one of her breasts. Sitting on his knees beside her, he touched her and called out, ‘Padma!’ Startled, she opened her eyes, saw her husband, reorganized her jacket, hugged the baby fast and said, “Oh! It is you”. There was at once joy and sorrow in her eyes. Tears, uncontrolled, flowed out of her eyes. There was love in her voice, her body shivered slightly and her heart beat faster. “Padma, yes, it is me. How are you? Give our boy into my hands,” he said and took the infant into his hands. He pressed it hard against his chest. A great show of affection flowed out of him, unchecked. He kissed his son on the forehead and pressed his lips over the baby’s chest and passed his own hands over the baby’s small hands and feet. His eyes grew wet. Padma put her hands over her husband’s shoulders and said, “The police have been coming here for four days now. May be, they’ll come again.” She spoke those words in great fear. She wept inconsolably and his jubba turned wet. Unconsciously, his hands touched the pistol. And he embraced her. 28

“Please tell me for how long you would be away from us all. And what do you get out of it all? The child has fever. Not a pie at home. And your father says the birth star is not good. A propitiatory pooja, costing a good deal of money needs to be performed. That alone would ward off the evil.” Her voice was deliberately kept low but her fright was obvious: her frame shivered. Raghuram sighed deeply and said, “Even if I explain it all, you’ll not understand it, Padma. Believe me I’m not fighting for selfish ends. It has a social purpose, for the sake of society.” “Not able to take care of the family, he talks of the country’s welfare,” said Subrahmanya Sastri in a tone that reflected his agony. “A glass of milk is all that the baby needs and this fellow talks of feeding the entire country.” Raghuram fondled the baby once more and handed it back to Padma. Then he looked into the eyes of his father, straight and sharp. “My dear revered father, tell me if all the Vedas and Vedanta you so avidly studied are providing a morsel of food to you. You mastered those Vedas and you believe this great land of ours needs them. To what purpose? You are accused and abused by the society around you of denying that knowledge to others. And how many are keen on learning them? Chaplaincy is no more an attractive profession. The temple authorities at Tirupati and Mantralaya offer to impart Vedic knowledge free of cost to all, irrespective of caste. And see the response! “The caste to which you and your likes belong is accused of looking down upon others. You constitute a miniscule minority everywhere; hardly two or three households in any habitation. You are all soft-natured and God-fearing. Tell me, who did you look down upon? Never were you rulers. You never wielded power: what harm could you have done to others? Some kind rulers gave you small land holdings. And what did you do with them? Unable to cultivate them yourselves, you leased them to sharecroppers and eventually sold them for a song. You reposed your trust in Vedas and passed for scholars. You had beneficial grace of the Goddess Saraswati but always shunned by the goddess of wealth. Not wealthy, your history had never been anything to boast of. In a feudal society one community makes another a scapegoat and prospers and you were those scapegoats. The society in its entirety did not gain. People like you, who chant Vedas and talk about Puranas would never understand the logic of this social conduct.” Raghuram’s was rather an emotional outburst. “Oh! Stop your lectures. What is it you are pursuing? Always afraid of police, you live in some wooded areas remotely located, far 29

from townships, burn buses, kidnap leaders of the lower rungs of society and create fear psychosis in the minds of authorities. I can’t see what you gain out of it. Do you ever realise the suffering you cause to the families of the victims of your activity? Just to placate you, the government announces a small price-cut in the sale of liquor ----- which only makes matters worse and distributes fallow-land which in any case is lying waste: a small landlord here and another there, you kill. Do you imagine all this would bring socialist order. If you can, you kidnap top-leadership. Stop production of country liquor, cigarettes and screening of blatantly vulgar cinemas morning, noon and night: may be, a programme like that will make sense. Kidnapping and killing the small fry and low-grade government employees ---- what will you accomplish?” poured out Sastri. “You will not understand it, father. This is the first step. When people at large wake up and see reality then surely an egalitarian society will emerge. And when that happens, the multitude and that includes you too, will have food to eat, clothes to wear and possibly a roof of your own, too. A new dawn, heralding new times when the vast numbers of the poor will lead a life of some quality, is bound to break.” Subramanya Sastri heaved a deep sigh. “Did any of you read Marx and understand Marxist thought?” At this point, he pouted his lips as if to indicate that Raghuram and his ilk did not study Marx thoroughly and said, “You know what Marx said, ‘Socialist doctrine will never gain a foothold in a country like ours. Unable to bear its pangs of hunger, somewhere a dog barks. A few bread crumbs thrown at it would silence it. You cannot expect food-riots here, the way they happened in Russia or China. When someone mumbles and moans “hunger,” a morsel of food materialises. A demand for shelter is more or less met by a choultry built by a landlord or a merchant prince who was wielding the stick and the demand dies. And an occasional piece of cloth distributed free puts a stop to that demand too. Underemployment takes care of unemployment. Poor quality wheat and rice, just enough to tide over the immediate pressure is dangled before the grumblers. One only needs to be clever to seize opportunities to build sky scrapers and move around in imported cars. Truly, such opportunities exist and more often than not, created.” He paused and went on. “In these circumstances, how do you expect a revolution to happen? A few like you who have half-baked ideas stay away from the masses – and yet expect a mass-upsurge based upon a new awareness. A peripheral contact with ‘Das Capital’ made you see how the people are taken for a ride but a large number of them who 30

saw this truth in its stark nakedness, joined the exploiting class and grew super-rich. Now, they have grown adept at the art of cheating people. Do you see another Sundarayya or a Prakasam Pantulu in the Andhra Pradesh of today? Show me a Nambudripad. The political leadership is busy building huge properties for itself. A new political class rooted in communal politics has come into being. No, a society built around caste and religion will not rise up to fulfill your dreams.” There was great pain in his voice. “I understand it, father. But our efforts are directed towards that fulfillment. It is inevitable that a few perish in the struggle. We are not thinking of ourselves and our generation. But surely the next generation will reap the fruits of our labour. Is it not a truism that that one who planted the tree is not likely to taste its fruit?” said Raghuram. Subrahmanya Sastri was unconvinced. “Father, here is some money. Please take it,” said Raghuram even as he tried to hand it over. “No, I don’t want that blood-stained money. I am steeped in our ancient literature, the four Vedas and the eighteen puranas. I now see a new society emerging in new colours. Sanskrit, Telugu and English too, I know. The entire Karmakanda (ritualistic practices) I know like the back of my hand. Do you know how I keep this body and soul together? I live on the gingelly seeds gifted to me during ceremonial functions by householders in the hope that the burden of their sinful lives will get transferred to my head. Now and then, I offer my services as a pall-bearer, of course for a consideration. And I don’t shy away from begging. This sacred thread across my chest permits it. I offer prayers thrice every day and chant Gayatri a thousand times everyday. I believe the evil that may visit me and my family would be mitigated through these prayers. You are born a Brahmin. Yet you discarded the sacred thread and chose to live a life full of violence, in thought as well as action. I would rather make my living as per my convictions than meet my requirements with that blood stained money that you are asking me to take. No, I’ll not take it,” said Subrahmanya Sastri very emphatically. In the distance, the sounds of whistles and stamping of booted feet were heard. “Well. I am going,” said Raghu and in a trice he melted into the darkness outside his house. Subrahmanya Sastri stanched the tears with his upper cloth. Padmavati held the baby to her bosom and grieved. The child was suckling at the dry breasts of the mother. Subramanya Sastri closed the door and dropped into his old cot. Sleep eluded him. Much as he wanted to, he could not muster strength 31

to mollify his daughter-in-law. For quite a long while, he sat lost in thought. Kuchipudi in Krishna district was known not only as the place where a unique style of Bharata natyam flourished. It was a centre of Vedic learning too. Subrahmanya Sastri was born into a family which inherited rights to enjoy the produce of a small landholding. Food, therefore, was no problem. He could use his time to better purpose: Vedic knowledge and acquisition of a grip over the eighteen Puranas. And he learnt English too. His name and fame spread through the entire district. Raghurama Sastri was his son, the only child. In time, the land which supported the family slipped away into the hands of farmers who tilled it. The new laws made it happen. He could have made a living by chaplaincy but his ego would not let him adopt the profession. Raghurama sastry developed an inexplicable aversion to the ancient knowledge. He graduated in Economics and was attracted by Marx and Mao. A steady job eluded him, in part due to his leftist leanings. And yet he married Padmavati and found himself in the twin cities where he went in the hope of finding a job. Subramanya Sastri’s wife died and nobody found any use for his erudition. Not surprisingly, totally frustrated, he too went to the twin cities to live with his son. Raghurama sastri delved deep into the leftist literature and developed a fixation on the idea that the haves all that they possess at the expense of the havenots. Prostitutes and beggars, not belonging to the productive havenots did not produce any wealth and so did not catch the eye of Marx. His mental horizons enlarged but the absence of a steady income made him sink into the abyss of poverty and bitterness pervaded his body and mind. He had to earn a living, support his wife and now his father too. Setting aside his ego, he joined the railways as casual labour. Soon he found his caste was a big handicap. Some of his classmates, purely on the strength of caste became officers. And quite many who joined the railways along with him were made permanent, some even became firemen. What galled him most was that he was denied equal opportunities because of his caste. Adding fuel to the fire, often he found himself having to kowtow to those who joined service along with him and quite often after him. All this sowed seeds of hatred and jealousy in him. Aggrieved, he fomented labour trouble and organized strikes. Soon he found himself jobless. Keeping the wolf away from the door became his main concern. While he saw many, unprincipled and unethical in conduct and character grow rich, he sank into abysmal poverty. He was not alone fated this way: many others too suffered similarly. 32

Now, his thoughts turned to find a way of bringing about social justice. He found his wife and father too burdensome, standing in the way of involving himself in labour movement and so, he cut himself away from the family. The government called him a naxalite. He could visit home only clandestinely, for the establishment saw him as a troublemonger. And they fixed a price tag on him, Rs. 50,000/ - dead or alive. Raghuram’s flight from police and home depressed his father beyond words. He ruminated over how Brahmasri Vedamurthy Subrahmanya Sastri’s transformed into Subbaiah, a lowly chaplain found good enough only to receive a gift of gingelly seeds, an appeasement for Sani. Thereby, in the mind of the giver, all the evil flowing out of the planetary position would now visit Subbaiah. But Subbaiah, the Subrahmanya Sastri knew how to ward off the evil-recital of Gayatri, a thousand times every day. There is some money too, meager though. And when his earnings did not meet his expenses, he didn’t mind offering his services to carry dead bodies to the crematorium. It is a demeaning service among the Hindus but among muslims, it is a service that could earn Allah’s blessings and so, a muslim readily puts his shoulders to carrying a coffin, whosesoever it might be, even if only for a few steps. A Brahmin offering services to officiate as a chaplain at religious functions dresses himself well, a way to catch the eye of a customer. But Subbaiah did not care for apparel: neither did he ever flaunt his scholarship. So, in the twin cities he remained an unknown commodity. Yet, he had to discharge his obligation as a father-in law. He cannot let his daughter- in -law starve for days together. Indeed, sometimes the hearth at home remained unlit for two or three days. It was unfair. And so he had to earn money, howsoever meager. It was same, whether he was Brahmasri Vedamurthy Subrahmanya Sastry or Subbiah ever ready to personate as ‘Sani’ and receive that gift of gingelly seeds.

* * * * *

Eight in the morning: clad in typical brahminical style, with marks of Vibhuti on the forehead and bare arms, small bundle of the sacred grass tucked under the armpits and almanacs of conveniently small size on them, the chaplains sat in rows on the stone platforms that abutted the frontage of every house in Isamia Bazar. One sported dark glasses without regard to the necessity, another munched tobacco-laced betel leaves, some reached the spot by walk and some on two-wheelers. Avadhani was their captain. Where to go 33

and what duties, each one of them has to perform there, Avadhani would decide. Avadhani runs two other branches of chaplaincy in the twin cities, one at Chikkadapalli and another close to Secunderabad station. After his morning prayers, including the Sahasra Gayatri he would chant everyday, Subbaiah also came to Isamia bazar. “Come, come dear oldy, Subbiah. I am afraid there is no demand for the likes of you today, I mean for those who are willing to accept the gift of gingelly seeds,” said Kotaiah Sastri, in a mockingly solicitous tone. Yet, he was kind enough to show a place to Subbaiah to sit. Kotaiah Sastri is about 35. He would officiate at a variety of religious performances. Yet, he cannot recite Gayatri properly, in the prescribed manner. Indeed he cannot intone any text of a given pooja, be it Navagraha Shanti, Sraddham or Satya Narayana Vratam. Often, he would recite the same mantra, mixing up intonations cleverly giving the ignorant householder an impression that the correct mantra as per the correct method was chanted. And many would particularly solicit his services. No wonder, Kotaiah Sastri was a rich man, owning a house and two or three building sites. Subbaiah sat next to him. Kotaiah Sastri made a grimace and literally moved a bit such that there was no body contact with Subbaiah. Now, he addressed Krishnamurthi, another priest: “Murthy garu, I cannot feel comfortable in the presence of those who accept the gift of gingelly seeds by incarnating Sani, even though they claim to be as good a brahmin as any of us.” Krishnamurthi whole-heartedly endorsed Kotaiah Sastri’s stand and even went further by saying, “Look at them. They look like the very picture of poverty.” “What of it? If only we do Sahasra Gayatri every day, the evil is warded off,” said Subbaiah. “Ah! Who would do all that? In fact, not many have the time for it,” said Kotaiah Sastry. Now, it occurred to Subbaiah: Why would none say such derogatory things about Christian or Islamic practices? But when it comes to a Hindu, even the small tuft of hair at the back of his otherwise clean shaven head is made fun of. Why, he wondered. However, he let the thought pass. Instead, he addressed Kotaiah Sastri in pleading tone. “Ayya Sastri garu, do you remember the request I made to you the other day?” “What is it?” asked Kotaiah Sastri. “I told you that a grandson is born to me. His birth star is Moola. So, a Navagraha Shanthi is warranted. If the homam is not 34

performed, our Sastras speak of danger to the life of bread-winner of the family. The Santhi is to be performed before the star-period is over. And the dead line is day after tomorrow. I request you all to be generous and help me out. Surely, I’ll meet the expenses not on a lavish scale but as my means would permit,” said Subbaiah. “What Subbiah, you augment your income sometimes even resorting to begging. How can you feed us, not to say give the fees due to each of us? You know, everyone here earns at least fifty rupees by merely marking attendance at a Shraddha. Those whose services are solicited for performing a Satya Narayana Vratam earn not less than two hundred and fifty rupees. And such of us as would officiate at marriages earn in thousands: not to say of the enormous fees we charge when officiating at the ceremonies connected to death. Santhi means every planet has to be propitiated with the suitable mantra. Fire-ceremony has to be performed and it is no joke. How can you hope to recruit our services, costly as they are? Forget it, old man,” said Kotaiah Sastri. “No sir, I am one of you or am I not? I pinned my hopes on the kindly help that I expected from you. If the Santhi is not performed, a great calamity is bound to befall my family.” “Nonsense! All these are unfounded fears. Don’t you worry? Even if you do not perform this santhi homam you are speaking of, nothing would happen. Don’t fear. If we come, do you know the loss we incur? Not taking into account a good meal, each of us will lose a minimum of fifty rupees. How do you then expect us to go to your house, to perform the Santhi you are talking of,” asked Kotaiah Sastri. “Does it mean that all you are doing is not based upon good faith?” asked Subbaiah. He was totally bewildered. Kotaiah Sastri now made a gesture that was at once a sly smile and a pity for Subbaiah’s unworldiness. He said, “How does it matter whether we believe in all these things or not? Isn’t it good enough if those who seek our services believe in the efficacy of all this? As for us, it is our livelihood and nothing more. My dear Subbiah, we cannot help you. Please go to Avadhani garu. May be he can help you.” And then he turned his face away from Subbaiah, took his upper cloth and used it to tie a knot around his forelegs and waist. That was the end of the matter as far as he was concerned. As if to indicate that he’ll have none of it any more, he took out his gold-rimmed snuff box, opened it and poured a bit of the snuff into his palm, closed the box and collected the snuff in his palm between his forefinger and thumb and inhaled it. There was a look of supreme bliss in his face. Subbaiah got up and walked towards Avadhani’s house. 35

Seated in a revolving chair, draped in ochre robes, lines of Vibhuti on the forehead and hands, with three garlands of rudraksha-s around his neck, Avadhani was in his office room reading the day’s newspapers. On the table beside him were two telephones. All the chaplains in the three centres were his men. Of course, as one who commissions their services, he has his discount from the earnings of all of them. His own personal services were available to big-wigs politicians, Industrialists, cine-stars and merchant princes. On hearing footsteps in the portico outside his office room, Avadhani took his eyes away from the Newspaper and looked at Subbaiah. “Oh! Tiladanam Subbaiah! What brings you here?” Subbaiah dared not sit nor did Avadhani offer him a seat. Subbaiah explained his mission. “How do you expect me to help you without making any payment whatever? Possibly, I might be able to fix some juniors for the other Grahams. But who do I find to receive your Tiladanam (gift of gingelly seeds)? There are two or three others at Secunderabad branch, but they would accept the danam only if you give a cash of two or three hundred rupees along with the gingelly seeds. You’re the only one always ready to accept this danam, without stipulating a sum of money to go along with it. You do not demur and accept whatever is given. But these others are not like you. What can I do for you? See if you can raise some money, Subbaiah,” said Avadhani. “What money can a beggar like me raise, Ayya,” said Subbaiah humbly. “Yes, the birth star is moola. It warrants Santhi. Someone has to pay a price – child, father or grandfather, one must die. I hear your son had joined the naxalites. Did he not send any money? In any case, there is always an encounter ready to gobble him up. When that is almost certain, why this Santhi?” said Avadhani trying to sound reasonable and sympathetic too. “All this agony of mine is to see that such a thing would not happen. There is not much time either. The star period would end the day after.” “What are you saying, Subbaiah? No, the period will last for another three days.” So saying, Avadhani pulled out an almanac and asked Subbaiah to look into it. “It is not correct. The calculation is wrong,” said Subbaiah. “Do you know who this Panchangakarta is? None other than Brahma Sri Veda Murthi Sachidananda Siddhanti. He is my guru. How dare you say his calculations are wrong? Okay, here is another almanac. This also says that Moola period comes to an end only three days from today.” 36

“This too is wrong. Avadhani garu,” said Subbaiah. Avadhani now looked straight at Subbiah and said, “You say all almanacs are wrong. What do you know! You think you are a pundit or a great astrologer! After all, you are an ordinary brahmin who accepts tiladanam. Your hauteur ill becomes you.” There was chastisement in Avandhani’s voice now. Subbaiah smiled “No, Avadhani garu. My calculations are not wrong. If you don’t mind, please look up the astrological journal. This month, planet Guru has a loop. So, time moves faster.” He said this and having lost all hope of help from Avadhani had walked out. Avadhani felt it was intrusive of Subbaiah to have come and wasted his time and went back to his newspaper. However, he felt ill at ease, took the phone and contacted a lecturer in the Department of Astronomy, at Osmania University. He placed Subbiah’s information before him and asked for clarification. After a while, the lecturer told Avadhani that Subbaiah was right. Avadhani turned speechless. Does it mean that Subbaiah was better at his calculations, all of it done using his fingers, than the authors of the two almanacs he depended upon so heavily? All the muhurtams he fixed, all the dates and days he gives as the days for performance of Poojas and Shraddhas to his clientele, all on the authority of the almanacs he consulted was wrong, at least marginally? If Subbaiah could calculate planetary motions, all on the strength of his brainwork, he must be a great man. Avadhani woke up to the reality. He got out of his chair, called his men and sent them on the errand of finding Subbaiah garu wherever he was and bring him along. But nobody was able to locate Subbaiah. Subbaiah went to Chikkadapalli, and Secunderabad in search of someone who would accept his Tiladanam. No, he could not find anyone. Wherever he went he found that priesthood had lost its soul; it is now business, a livelihood. He did not find a single brahmin who would accept tiladanam, unless a hefty cash payment went with it. Some brahmins were aghast that they were approached at all with the proposition. He found that the whole profession of chaplaincy was full of greed, ego, ignorance and worst of all, a false pride. It occurred to him that the brahmins incurred the wrath and hatred of the rest of the society because of this. He came home around ten, that night. Padmavathi did not eat yet. She was waiting for her father-in-law, so that they could share a little of the small quantity 37