TUYỀN ĐOÀN HUỲNH NGÂN,

MIGRANT ARCHIPELAGO

Planting roots as migrant bodies in Torcy, between Paris and Disneyland

RESEARCH

TU Delft / Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment

Master of Science, Architecture track Interiors Buildings Cities / Independent Group Design thesis / February 2023 - January 2024

ABSTRACT

ABSTRACT

Between 1980 and 2000, as an act of humanitarianism for their former colony, France received a large influx of 200,000 immigrants fleeing their countries due to post-decolonization conflicts (Figure 01). This study explores the settlement of migrant communities in Torcy, a suburban enclave positioned between Paris and Disneyland. Its subject directly comes from people experienced forced migration or refugeehood from former French colonies. The research leverages on the theoretical concept of archipelago of resettlement, grounded in an archipelagic narrative and horticultural inspiration. Investigating interconnections between diasporic groups, it emphasizes restorative microcosms among people, plants, and the river, advocating for a communal healing typology called the “Migrant Archipelago”.

The research translates into architectural manifestation through an isolated industrial warehouse on the Marne riverbank of Torcy, where migrant bodies can engage in productive gardening and trading, and Torcy’s peripheral entities can together serve a common purpose to mend the town back with its riverscape. The architectural intervention along Marne's riverbanks rejuvenates migrant solidarity, rekindling neglected river culture.

Ethnographic immersion delves into migrant microhistories, revealing their heritage preservation strategies. Engaging diverse narratives through literature reviews and interviews, it transcends cultural-political differences. The research advocates collective healing, uniting diverse migrant experiences through the allotment culture that thrives on democracy and altruism. Focused on refugees from French colonies, this study illuminates empowered healing ground through gardening and communal engagement, contributing to the existing archipelagic narrative.

Keywords: diaspora, refugeehood, healing memories, Torcy, migrant, archipelago.

NOTE ON POSITIONALITY

01. NOTE ON POSITIONALITY

My interest in diaspora and migration originates from my Vietnamese heritage, and rooted in the narratives of families who navigated the tumultuous eras of French colonial rule (1888 - 1945) and the Vietnam War (1954 - 1975). Like numerous Vietnamese families worldwide, my family has people forced into seeking asylum elsewhere to avoid wartime consequences and persecution, scattering through the oceans in pursuit of a promising future for the successive generations. Recognizing my privileged position in exploring this topic academically, I am conscientious about approaching this research without causing harm or objectification to any individuals or subjects mentioned.

It's crucial to acknowledge that the community I aim to design for in Torcy extends beyond Vietnamese origins. While I refer to them as the migrant community, it's imperative not to homogenize this term to represent all migrants uniformly. This label risks oversimplifying diverse perspectives and experiences, overlooking the significant differences among various migrant groups. This is because it speaks greatly on the essentialist view that those who fled have a similar international leftist political stance [1]. In reality, this is not true. For instance, the divergent migration paths are anticommunist Southern Vietnamese or monarchist Iranians. This research emphasizes finding common ground for healing through sharing space and working together while respecting that not everyone who experienced displacement has the same political or cultural viewpoint. Therefore, I aspire to continue the research with care and empathy for individuals and families who value resiliency and continue the momentum to keep on living through disparity.

My research underscores the pursuit of common ground for healing and resilience by fostering shared spaces while respecting the array of cultural and political viewpoints among those who have experienced displacement. Therefore, I became conscious in terminologies used in describing the “protagonists” and “antagonists” upon which the work is reacting on. However, if I inadvertently use incorrect or inappropriate terms, I do accept open conversation about the matter and open to learning more about the intricate terrain of diaspora.

02. INTRODUCTION

This research paper examines the mental fatigue of diasporic bodies, specifically the settlement of migrant populations in Torcy. This town is a suburban enclave positioned between Paris and Disneyland, a permanent home to one of the largest migrant communities in Île de France, and a competition ground for the 2024 Olympic. As its identity unraveled, the placement of the design proposal in Torcy is an opportunity to re-evaluate the town’s edge condition with the Marne to activate not only a common ground for the migrant community but also its potential to become a counterstatement to the Olympic landscape.

Migration is constant, and happens on all level of beings. Nevertheless, migrant bodies always face serious stigmatization by the native population in the land they settle in. The scope of this research concentrates on migrant humans and plants from French former colonies, who were marked as exotics during French Imperialism, now, they are continued to be labeled as unwanted and invasive. Parallel to this scope in the context of Torcy, the town’s peripheral entities form a collective constellation with their existing strengths to ultimately mend this fragmented town back together.

Anchored in the theoretical concept of an archipelago and inspired by horticultural practices, this study navigates from theory to practical realization via the materialization of an architectural typology derived from the research with the name Migrant Archipelago. It underscores the social potential inherent in productive gardens and the healing quality of gardening, serving as the impetus for the design thesis. This architectural intervention envisions an innovative communal space along the Marne riverbank, crafted with care for Torcy's migrant bodies and its populace. Nested within this architectural embodiment are

initiatives that foster self-sufficiency and resilience among migrants, revitalize the river culture, thus, reinstating a sense of completeness to the locality.

With that said, this text opens with a problem statement about the mental fatigue of people endured postconflict forced migration, resettling in new places as refugees. Next, the literature reviews study the existing discourse on archipelagic thinking (Evyn Lê Espiritu Ghandi) [2], diaspora (Tiffany Chung) [3] and qualities of the allotment culture (David Crouch and Colin Ward) [4]. Then, the research question conveys a desire to design for the tired, migrant bodies through the regenerative provisions of green space, communal activities, and productive gardening. Zooming in on the context of Torcy, the research methods includes ethnographic research (home-stay, several interviews and a workshop), and fieldwork in Torcy and the surrounding crucial landmarks such as the Garden of Tropical Agronomy, the Menier Chocolate Factory, and the Olympic Stadium. The ethnographic research hones in on the micro histories of former refugees in Torcy in order to build an urgency to bring awareness to the yearning and generational trauma caused by refugeehood, and accumulate specific interventions to formulate the programming of the Migrant Archipelago. These interviews were done with former war and economic refugees, predominantly from former French colonies, who reluctantly uprooted their lives and resettled permanently in Torcy and the surrounding towns of Seine êt Marne. The fieldwork exposes important history on the stigma of invasive species through French colonial past in horticultural practice on the exotics, which subsequently connects this perspective to their modern view on migrant community today, not just in Torcy.

2. Gandhi, Archipelago of Resettlement, 2022.

3. Tiffany Chung, “Vietnam, Past is Prologue,” James Dicke Contemporary Artist Lecture (lecture, Smithsonian American Art Museum, May 2, 2019).

4. David Crouch and Colin Ward, The Allotment Its Landscape and Culture (Nottingham: Five Leaves, 1999).

DIASPORA IN FRANCE

07

03. DIASPORA IN FRANCE

The global refugee crisis of the 1970s to 1990s stemmed from intricate political, social, and economic circumstances. This thesis chose to focus on the French context because France had an extensive colonial presence across the world. As these colonies gained independence, many encountered internal conflicts and struggled to establish stable governance. In the context of France and its former colonies, this era saw a surge in refugee movements due to the aftermath of colonization and the struggle for independence in newly liberated nations, leading to political turmoil and instability. This instability led to authoritarian rule, civil strife, and conflicts within these nations. Subsequently, people sought refuge to escape persecution, political oppression, and human rights abuses in their homelands. While larger political parties were seeking for liberation and freedom, the ordinary people salvaged their belongings and had to make the life-alternating decision, whether to stay or leave. This research pivots to the population that left their homelands and permanently resettle in France [5] .

For example, The Algerian War of Independence also prompted Algerian nationals to seek asylum in France due to the conflict and its aftermath. Additionally, after the Vietnam War in 1975, France experienced an influx of Vietnamese refugees escaping the communist regime, and most of the population was first relocated to Noyant-d'Allier (Southern France) as an introductory to their new culture (Figure 03). After proper integration, Vietnamese war refugees were relocated to the Seine êt Marne region of the Île-de-France. Citizens from other former French colonies faced similar challenges post-independence, leading some to migrate to France in search of safety and better opportunities. Specifically, there were diasporic migration paths from newly liberated French colonies such as Algeria, Tunisia,

5. OECD, Trends in International Migration, 1997, 97–103, https://doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-1997-en.

Morocco, and Senegal to the Seine êt Marne region. These refugee movements were shaped by the historical legacies of colonization, struggles for independence, and subsequent political upheavals in the decolonized nations (Figure 04).

Once a person becomes an exiled citizen looking for relocation, the embodiment of home no longer lies in the interior space of their comforting kitchen, living room, or bedroom. Nevertheless, it lingers on in their memories and the valuable items they took with them before departure. By going through immense hardship to reach their destination, refugees from this period found better self-sufficiency to present themselves in job and housing market, often in more blue-collar sectors. Moreover, ethnic communities took root in France experienced more problems with internal family due to the mental fatigue of post-conflict migrant rippled into the next generation, which results in unspoken generational-trauma and long-term struggle to truly feel belonged in their host country [6] .

It is your parents who ran, but it’s you who continues running long after they have come to rest. [7]

— Musa Okwonga (b.1979, London)

In essence, the refugee crisis of that period was a result of a complex interplay of historical, political, and social factors, compelling individuals and families to seek refuge, with France serving as a destination for many seeking safety and stability. When one’s homeland is in jeopardy of a new political regime due to war or liberation, seeking permanent resettlement comes with many issues, including the cross-culture precarity, multigenerational differences, and perpetuated narrative of being the others. Forced migration challenges people to evaluate the axiological aspect of a home [8]

6 Jeremy Hein, “Refugees, Immigrants, and the State,” Annual Review of Sociology 19, no. 1 (1993): 43–59, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.19.080193.000355, 53.

7. Raphaëlle Red, “Sites of Diaspora Include,” The Funambulist: Politics of Space and Bodies, September 2022, 34.

8. Evyn Lê Espiritu Gandhi, Archipelago of Resettlement: Vietnamese Refugee Settlers and Decolonization across Guam and Israel-Palestine (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2022), 177.

Refugee crisis Phase 1 (+3,000)

Refugee crisis Phase 2 (+5,000)

Torcy, introduced before as a suburban nestled between Paris and Disneyland, witnessed an extraordinary surge in its population. The town, which previously had around 4,800 inhabitants before the crisis, encountered a staggering demographic shift, escalating to a population of 18,681 individuals by 1990. This influx caused the town's population to swell almost five times its prior population size (Figure 04). This unprecedented population growth in Torcy exemplifies the profound impact of the refugee crisis, not only on a global scale but also on the local level, drastically reshaping the demographics and cultural landscape of the town.

Torcy and its neighboring towns of the Marne Valley, (Noisiel, Varies, Bussy Saint George, etc.), house the

largest Vietnamese migrant community outside of Paris, and a large Algerian and Cambodian migrant community. The sudden surge in residents profoundly impacted the town's social fabric, infrastructure, and communal dynamics, fundamentally altering its landscape and character within a relatively short span of time [9] .

9. Eric Hacquemand, “La Communauté Asiatique Met Le Cap à l’est,” leparisien.fr, January 27, 2001, https://www.leparisien.fr/seine-et-marne-77/la-communauteasiatique-met-le-cap-a-l-est-27-01-2001-2001917516.php.

Chung, Tiffany. “Vietnam, Past Is Prologue.” Seventh Annual James Dicke Contemporary Artist Lecture. Lecture presented at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C. May 2, 2019.

Summary — This lecture summarizes the scope of Chung’s artistic practice and academic discourse through her first-hand experience as a refugee of the war in Vietnam, ethnographic findings, archives, and formal research. She is an expert in cartography and uses it to map traces of migration, disruption, dislocation, and divergence based on a combination of said methods. Through an articulation of intentional dots, and lines, micro-histories of Vietnamese refugee patterns start to emerge and create a complex pattern that is not recorded formally by any sort of database/mapping before.

For the Smithsonian Asian American Museum’s annual James Dicke Contemporary Lecture, she narrated the storyline behind her solo exhibition at the same institution called “Vietnam, Past is Prologue”. As the boundaries of countries and cities are continuously being challenged or erased, she conducts intensive studies on the impacts of geographical shifts and imposed political borders on different groups of human populations. Chung’s work in cartography (map making) is valuable to the original groundwork to help visualize the suffrage of many refugee families that stand invisible in the formal academic discourse. And while unpacking this ethnographic work, an architectural response can reassure what has been neglected in the current channels of desensitized social views.

Fragmented stories of how the war took a toll on our families were the lullabies that transcended our childhood and thrust us into adulthood. Vietnam is one of the most

impactful words in my own dictionary of life, this word brings back a familiar sense that transports us home. It also has the power to bring back the most ominous chapter of our memories. There are wounds that don't heal. [10]

Integration — While the represented work is striking and informative, this lecture on Chung’s recent exhibition about the aftermath of the Vietnam War through cartographic method focuses on mapping between Vietnam and the United States, with untold stories by Vietnamese people filling in the historical gap. It mentions lightly the forced migration pattern of Vietnamese people into Europe, especially in France. Her work in cartography (shown explicitly in this lecture) is at a unique crossroads between art and research (Figure 06). There was serious attention to the Vietnam - United States diaspora, as shown through Chung's work, and a lack of communication on how the refugee crisis occurred in Europe, especially France. Therefore, with this thesis focus on one specific town of Torcy where France direct a lot of their refugees from Vietnam to, more micro-histories can be added to the network of post-war diaspora.

Gandhi Evyn Lê Espiritu. Archipelago of Resettlement: Vietnamese Refugee Settlers and Decolonization across Guam and Israel-Palestine. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2022.

Summary — The introduction chapter sets a narrative framework for the book. Gandhi shares the initial findings that sparked the journey into the archipelagic routing to uncover untold stories of Vietnamese refugee settlers in Guam and Israel-Palestine (nation-states that U.S. Imperialism occupies, and both historically went through various colonial turmoil). Other findings include the usage of the term refugee settlers not as a new phenomenon but has been used (or misused) before, with one instance describing the “innocent” white settler narrative of refugeehood on Native American land (American national identity). While the book talks about a topic not related to the scope of this thesis, the significance of this framework might be able to empathize the necessary narrative for how all migrants who fled their country due to the conflicts. The opening text view Vietnam post-war in 1975 as one island in an archipelago of diasporic collectivity, connecting Vietnamese refugees worldwide as a common mass of land/water dialectic. Nước is the word for water and nation/homeland/country, this is a duality without division, a contrast without contradiction.

Vietnamese refugees resettled worldwide, forging new islands of belonging in their respective countries of asylum. Collectively, these islands make up an archipelago of resettlement: a postwar diaspora connected by the fluid memory of a beloved homeland, lost to war – p. 2

Integration — Using the concept of nước to familiarize how Vietnamese people become refugee settlers and formulate the theoretical constellation of archipelago of resettlement, can it also become a concept to sympathize with the Vietnamese community who settle in the imperial lands such as France, United States, Japan, and many more? While sharing incredible new findings on the term “refugee settler”, there is still a gap in ethical forms of relation between the three forces –refugee settlers, indigenous subjects, and the imperial colonists. The general understanding of refugee, not just exclusively Vietnamese refugee, are predominantly centered around displaced people finding a sense of home in well-off countries. This book have called out for decolonization in occupied nation-state, affecting the new generation of their inhabitants, thus, may have risked the citizenship that refugee settlers gain through neutralization from the imperial force. It is one of the fundamental references for this thesis for integrating the archipelagic mindset to refugees and migrants, and for their collective yearning for their homeland (Figure 06). Thus, it subsidies the problem statement of this thesis and assists the transition of a theoretical concept into something tangible for the community.

Crouch, David, and Colin Ward. The Allotment its landscape and culture. Nottingham: Five Leaves, 1997.

Summary — Allotments stand as havens for cultivation, often nestled on the outskirts of bustling suburban life where the pace grows more hectic and living expenses soar. Here, a fundamental desire to cultivate one's own produce or achieve self-sufficiency unites a community composed of individuals, wildlife, and a myriad of plants, often more diverse than the surrounding cities and towns. An allotment embodies a utopian essence, a verdant space where anyone can claim a parcel of land and foster growth, unrestricted by conventions.

"The Allotment," originally published in 1997, serves as the definitive exploration of these spaces. It intertwines the spoken narratives of plot-holders with detailed depictions of regional peculiarities, from pigeonfancying to seed collection and leek competitions, offering a lens through which to view British society and history. This narrative remains just as pertinent today, an indispensable resource for those intrigued by social history, land ownership, and gardening in 21st century Britain.

Within its pages, the book reveals how allotments have served not only as places for growing produce but also as hubs for community engagement and social interaction. It emphasizes the valuable social connections and communal spirit found within these spaces, where people from various backgrounds come together to cultivate friendships and share knowledge (Figure 08)

Integration — Crouch and Ward's text reveals the quality of the allotment that goes beyond tending one's own garden. When multiple gardens are grouped

together, you get an allotment, a garden typology that thrives on diversity, democracy, and altruism. Anchoring in the local and based on values such as humor, generosity, nourishment, it brings leisure and productivity together through quotidian values . Through the allotment's universal value, it can synthesize with the archipelagic framework of migrant bodies, a place to host social interactions. With that said, while its original purpose is not meant for a specific type of healing, by correlating the act of nurturing, cultivating, and socializing through productive gardening, migrant bodies can finally have a place for healing their mental fatigue (Figure 07). Not only that, these bodies pertain to both migrating humans and their plants, providing them the freedom to express their own horticultural practice.

05. PROBLEM STATEMENT & RESEARCH QUESTION

Diasporic beings carry the burden of their homeland in terms of displacement trauma, mental fatigue, and lasting alienation from their refugeehood [11]

As people settle down and expand their families, this trauma becomes a silent battle between multiple generations. With the word integration carrying a negative connotation of possibly rejecting one’s heritage to assimilate with a new permanent-resettled home, can there be a place for these memories to heal and be celebrated? This research journey is rooted in the ambition to respond to the complicated (yet, unspoken) issue that comes with post-migration, and subsequently, cultural assimilation.

Preliminary research question

How does architecture become regenerative therapy for displaced communities?

Primary research question (Figure 10)

01 GENERAL INTRODUCTION

How does a productive garden become a regenerative therapeutic place for the migrant community in Torcy and its peripherals to reconnect with their roots?

Between 1980 and 2000, as an act of humanitarianism for their former colony, France received a large influx of 100,000 immigrants fleeing the Vietnam War. Simultaneously, there were migration paths from newly liberated countries such as Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, and Senegal to the Vallée de la Marne region of Île de France 1 When one’s homeland is in jeopardy of a new political outlook due to war or liberation, seeking refugee and permanent resettlement comes with many issues, including the cross-culture precarity, multi-generational differences, and perpetuated narrative of being the others. Forced migration challenges people to evaluate the axiological aspect of a home 2. Once a person becomes an exiled citizen looking for relocation, the embodiment of home no longer lies in the interior space of their comforting kitchen, living room, or bedroom. Nevertheless, it lingers on in their memories and the valuable items they took with them before departure.

The city is an artifact filled with ideas, hopes, and dreams from its people [12]. In exceptional circumstances such as those experienced refugeehood, the architecture of the place people chose to settle down was not the priority, but rather, recreating and tracing back to how their familiarities are the beginning of creating a home. In terms of the city they once knew become part of them, and through restoration and hard work, they offer the new place their memorabilia, maybe within a market, a store, a living room, a bedroom, or a home garden. The issue entails the degradation of intangible heritage and the introduction of displacement trauma that can surpass one generation to another. Therefore, translating the intangible aspect of cultural heritage to tangible is part of the home-making process for migrant people [13]

This study emphasizes on the interwovenness and solidarity among peripheral entities within the diaspora, accentuating the microcosm of restoration observed among migrant bodies that are casted as exotic / invasive, in the context of Torcy.

Secondary questions

– What is the role of architecture in this productive garden?

– Can practicing home-making and personalization in a public space be part of cultural heritage preservation?

– What is the cultural stratification embedded into the architectural intervention in the garden?

It is your parents who ran, but it’s you who continues running long after they have come to rest 3 Musa Okwonga (b.1979, London)

– What are the possibilities for a garden to be the counter-statement for the neocolonially charged landscape like the Olympic game?

The research anchors itself on Torcy, an exurb on the Marne, a middle town between Paris and Disneyland, a permanent home to one of the largest migrant communities in Île-deFrance, and a competition ground for the 2024 Olympics. As its identity unraveled, the placement of the design proposal in Torcy is an opportunity to re-evaluate the town’s edge condition with the Marne to activate not only a common ground for the migrant community but also its potential to become a counter-statement to the Olympic landscape.

– Which are the factors that make up a cohesive garden of migrant bodies?

This study aims to establish an architectural typology that hosts and nurtures the migrant people and vegetation while embodying the regenerative healing capabilities of productive greenspace. The study inclines to incorporate the incremental participatory process to maintain the longevity of such typology.

Topic — Home-making in the public realm for people experienced forced migration.

Who?

Why?

How does a productive garden become a regenerative therapeutic place for the migrant community in Torcy and its peripheral to reconnect with their roots?

refugeehood migrants

multi generational

home-making gardening healing

What?

Where?

11. Tiffany Chung, Vietnam, Past is Prologue, 2019.

12. Mark Pimlott, “About Looking,” Interiors Buildings Cities Lecture (lecture, Falcuty of Architecture, Urbanism, and the Built Environment, September 23, 2021).

13. Juliet Millican, Carrie Perkins, and Andrew Adam-Bradford, “Gardening in Displacement: The Benefits of Cultivating in Crisis,” Journal of Refugee Studies 32, no. 3 (2018): 351–71, https://doi. org/10.1093/jrs/fey033, 351.

1 OECD, “Trends in International Migration 1997,” Trends in International Migration, January 1997, pp. 97-103, https://doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-1997-en, 97.

2 Envyn Lê Espiritu Gandhi, Archipelago of Resettlement Vietnamese Refugee Settlers and Decolonization across Guam and Israel-Palestine (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2022), 177.

Figure 10. A breakdown of the primary research question, in terms of overall main topic, the 4-Ws. With this diagram, the motivations and outcomes are clearer, and the trajectory of both the research and design have more interwoven qualities.

3 Raphaëlle Red, “Sites of Diaspora Include,” The Funambulist: Politics of Space and Bodies, September 2022, pp. 3035, 34.

06. ARCHIPELAGIC THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

While possessing a unique edge condition with the Marne and the Olympic game, this research seeks to empower precisely the migrant community of Torcy for its agility while facing marginalization. Through the research development, the chosen parts are of different scales based on their relationship to the city of Torcy. Because diasporic paths and forced migration occur globally, framing the project at this physical location makes the study more detailed and unique (Figure 09)

The choice to center this thesis on Torcy emerges from a personal connection with Mr. Tiến's family, whose migration journey unfolded amid the refugee crisis. Tiến and his parents, war refugees from Saigon, resettled in France in 1991 (Figure 11). Despite residing in Torcy for over three decades, Tiến continues to experience a profound sense of longing for his homeland, Vietnam [14]. This poignant narrative serves as a cornerstone in exploring the complexities and nuances of the migrant experience within the context of Torcy.

Archipelago of resettlement — Through various migrant bodies similar to Mr. Tiến and his parents settled in Torcy, the town became part of this constellation of islands. The archipelagic framework, introduced by Evyn Lê Espiritu Ghandi, illuminates the linkage between refugees between each other and their homeland [15] It metaphorically represents how these communities, amidst displacement, forge collective nostalgia and interconnectedness, forming an archipelago as a tribute to their origins. Collectively, these islands form an archipelago of resettlement, which figuratively maintains an image of homeland in their memories. Only by recognizing its existence that this archipelago can be realized into a tangible landscape.

This metaphor, often invoked in the context of diaspora and migration, signifies the fragmented yet connected nature of these communities settling in new territories. Just as an archipelago comprises various islands scattered across waters, the notion metaphorically mirrors the dispersed yet interlinked communities across different regions (Figure 12).

In the context of resettlement, this concept highlights how individuals and families, despite being physically scattered, maintain a strong emotional and cultural bond with their homeland [16]. It acknowledges the diverse experiences and memories that shape their identity, serving as a cohesive force within the diaspora. With that said the archipelagic way of thinking goes beyond the dehumanizing centripetal force of globalization, which is a by-product of neo-colonialism. While the archipelago of resettlement is a non-physical landscape only by recognizing its existence can it be realized into a tangible landscape. The archipelagic idea doesn't merely signify geographical dispersion but embodies a shared emotional and cultural narrative among displaced communities (Figure 13)

14. Tuyen Lê, A Conversation with Mr. Tiến, March 17, 2023.

15. Refer to the previous literature review on page 12 for her book, Archipelago of Resettlement: Vietnamese Refugee Settlers and Decolonization across Guam and Israel-Palestine

Postmemory — In 2021, France had 10.3% immigrant population, compared to 6.5% in 1968. Over 50 years, immigrant origins diversified, with newer arrivals representing a broader array of countries. The second generation's situation approached that of nonimmigrants more than their parents'. Immigrants' living standards were 22% lower than non-immigrants, but this gap reduced to 19% for those with two immigrant parents and 6% for those with one immigrant parent. However, while it is now a different time than the refugee crisis 50 years ago, inequalities persisted, notably in employment and housing. Descendants of immigrants reported more discrimination, especially those of non-European origins, indicating higher rates than immigrants of the same origins and the nonmigrant population [17] .

For those whose past include refugeehood, there is also “refugeetude” [18], a constant state of feeling unwelcome, unsettled, and not entirely at home even after being permanently settled and living their lives. Connecting this issue to the diaspora in France during the refugee crisis, As a result, the condition is passed down to the next generation as post-memory [19] . It is the collective cultural trauma that the next generation subconsciously inherited from the generation that migrated.

Architecture of a place that refugees settle down would not be of choice. So, that implies the process of recreating their familiar settings becomes the key to making the architectural context feels like home again. The city they left behind becomes a part of them, and through the work of retracing, they can offer the new place their memories and diversify its culture.

their past through gardening their own vegetables...

17. Rouhban Odile and Tanneau Pierre, “Immigrants and Descendants of Immigrants,” Insee, April 11, 2023, https://www.insee.fr/en/statistiques/7342924?sommaire=7344042.

18. Envyn Lê Espiritu Gandhi, Archipelago of Resettlement Vietnamese Refugee Settlers and Decolonization across Guam and Israel-Palestine, 2022, 128.

19. Marianne Hirsch and Marianne Hirsch, “Postmemory's Archival Turn,” in The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2012), pp. 277-250.

07. MIGRATING GARDENS

An archipelagic landscape — During the urgent exodus from one's native land, individuals often lack the opportunity to pack extensive belongings, necessitating travel with minimal weight. Hence, in the haste of departure, people tend to carry only a few changes of clothes, valuable jewelry (often used as emergency currency and stowed discreetly in their carry-ons' false-bottom), cherished letters, and photographs. Additionally, among the items that can be clandestinely nestled into luggage are vegetable seeds. Initially inconspicuous, these migrating seeds acquire profound significance when successfully cultivated in the newfound settlement, serving as a tangible link for refugees to their homeland. [20]

The cultivation and nurturing of these growing plants, leading to harvest, sharing, and consumption, play a pivotal role in alleviating the concealed mental exhaustion experienced by many refugees (Figure 14). This process serves as a therapeutic outlet, offering semblance of food sovereignty, and relief from the emotional fatigue deeply entrenched within them.

Food is a piece of it, but it’s so much more about the social issues and people wanting to take back control of their lives in some way. Gardening creates autonomy. You’re reshaping the space around where you live. [21]

Today, migration is a ubiquitous phenomenon, yet it's important to acknowledge the stigma surrounding refugeehood (linked to forced migration), impacting both migrant humans and plants, often deemed invasive and unwelcome upon arrival. The notion of migrating gardens encapsulates the archipelagic mindset, representing how migrant gardeners cultivate their native produce in new surroundings to uphold ties with their homeland (Figure 15)

20. Tuyen Lê, Conversation with Tuấn Mami, February 27, 2023. 21. James Atherton, “Planting Seeds in Refugee Camps,” Regenerosity, August 20, 2020,https://www.regenerosity.world/ stories/planting-seeds-in-refugee-camps.

in Iowa, United States in 1981. With most seeds considered to be invasive species according to the States’ agricultural standard, he keeps his vegetables in pots to prevent native soil erosion or overgrow. He takes on the migrant garden as a way to feed his nostalgic tendency for nước (homeland), as well as establishing his roots again in a foreign land. Around April of each year, Mr. Nô would start propagating his garden near the kitchen, where the light comes in the most during the afternoon. (Des Moines, 2020. Source: Mary Lê)

MIGRATING GARDENS

(Source: Léon & Lévy / Roger-Viollet Cirad, 1907)

This sustenance of connection not only fosters cultural continuity but also serves as a source of solace, countering the mental fatigue experienced by migrant communities in the wake of post-war diaspora.

A former product of colonialism — At the edge of Bois de Vincennes in Paris' 12th arrondissement, lies the Tropical Agronomy Garden, a place intertwined with historical significance from the 1907 colonial exhibition (Figure 18). Though often unrecognized by the public, the garden holds remnants from this period - neglected colonial pavilions, obscured statues, and pathways leading to vestiges from Madagascar, Indochina, and Tunisia. This was perpetuated as a showcase of French colonial success by parading people imported from their colonies, like a human zoo [22] .

In recent history, amongst the migration path to France, people of the former colonies uprooted their lives and carried with them the plant seeds as a memento of their homeland. However, during the era of French imperialism, the acceptance of importing both humans and plants from colonies onto French soil raises poignant questions (Figure 20). These 'exotics' were often considered mere instruments for the pleasure, wealth, and advancement of the French imperial machinery.

The 1907 Colonial Exhibition notably featured human zoos, but today, only the colonial pavilions remain in the Tropical Agronomy Garden as vestiges of that era. Human zoos were subsequently banned during the 1931 exhibition due to evolving mentalities catalyzed by African soldiers' participation in WWI and increased knowledge about colonized territories [23]. Presently, knowledge of these events relies on oral history as they are often omitted from formal education due to the shameful/taboo past. This oral tradition, conveyed

22. Stéphanie Trouillard, “Ghosts of France’s Colonial Past Linger in Paris’s Tropical Gardens,” FRANCE 24, 2005, https://graphics. france24.com/paris-tropical-gardens-keep-wwi-secrets-colonialpast/index.html#/laboratoire-agronomie.

23. Kyra Alessandrini, “Lieux Oubliés: Les Vestiges Des Expositions Coloniales Au Bois de Vincennes,” RFI, August 21, 2018, https://www.rfi.fr/fr/france/20180820-lieux-oublies-vestigesexpositions-coloniales-bois-vincennes.

through familial accounts and communal stories, risks fading away from collective memory of French colonial past.

Beyond the displays of human for entertainment, the exposition was also a celebration for the French horticultural success. This colonial catalyst was furnished with greenhouses backed by the French chocolate giant Menier [24], this site can be identified as France's initial migrating garden (Figure 22 - 28). Scientists used the facility to study and develop plant species, mostly cash crops destined for African plantations, such as coffee, cocoa, vanilla, nutmeg and banana. The garden also made it possible to study the potential of exotic plants to acclimatise to the more temperate French climate. In 1902, a national school for the study of colonial agriculture was added to train those intending to pursue a career in the colonies. Students could study plants in one of the greenhouses under the one-year courses sponsored by the Ministry for Colonies, and full-time biologists continued their research in another one [25]

24. Corinne Nèves, “Voyagez Dans Le Temps Au Jardin d’agronomie Tropicale Du Bois de Vincennes,” Le Parisien, July 27, 2020, https://www.leparisien.fr/culture-loisirs/sortir-regionparisienne/voyagez-dans-le-temps-au-jardin-d-agronomietropicale-du-bois-de-vincennes-27-07-2020-8359443.php.

25. Stéphanie Trouillard, Ghosts of France’s Colonial Past Linger in Paris’s Tropical Gardens.

Regrettably, these historical truths have not found their way into mainstream educational curricula. The echoes of these events and the accompanying knowledge primarily reside in the collective memory passed down through familial anecdotes and community narratives.

It's crucial to recognize that these greenhouses projected a colonial exoticism rather than embodying an archipelagic significance. Today, the continuum manifests as migrating gardens and their gardeners, originating from former colonies, seeking refuge in France. Nevertheless, the objectifying perception of 'exotics' has evolved into a contemporary equivalent of 'foreign,' 'other,' or 'invasive,' further complicating the process of migrant bodies establishing roots.

(Source:

Decolonizing the invasive narrative — Expanding upon a more empathetic perspective regarding both invasive flora and migrant individuals, they collectively contribute to the diversification of both tangible and intangible landscapes [26]. The fundamental objective of this cultivated "garden" lies in providing a sanctuary for individuals to engage in the act of establishing a home within a communal space. Precisely, it embodies the liberty to transpose their cultural heritage into the tangible practice of horticulture, utilizing their preferred tools akin to an outdoor living area. During my visit to the Torcy allotment garden community in March 2023, I witnessed the unobtrusive nature of productive gardening, fostering the gardener's profound connection with nature and their neighboring gardeners (Figure 30). The consequence is an intentional yield meant for communal sharing, thereby fostering an environment conducive to showcasing significant biodiversity, both in terms of the land itself and the interpersonal bonds forged. This interlinked network of allotments serves as a catalyst for social unity among diverse migrant backgrounds.

Healing through heritage preservation — The broader significance of gardening and exposure to green spaces is well-established in promoting both physical and mental wellbeing. Cleve West (Figure 29), a garden designer from London, shared insights:

I’m a gardener by trade, a garden designer. So I know about the health benefits of having green space. I’ve done a garden down in Salisbury called Horatio’s Garden, and that’s attached to a spinal unit. So I’ve seen first-hand, what a positive effect a green space can have on people who have been injured or who are just depressed. You can imagine being in a spinal unit, lying in bed for literally six months staring at the ceiling, and then, being allowed

26. Kari A. Hartwig and Meghan Mason, “Community Gardens for Refugee and Immigrant Communities as a Means of Health Promotion,” Journal of Community Health 41, no. 6 (2016): pp. 1153-1159, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-016-0195-5, 1157.

out into the garden, just seeing people burst into tears as they come into that garden. And to a certain degree, we’ve all taken this experience for granted. [27]

Moreover, beyond its therapeutic dimensions, produce gardening emerges as an economically sustainable approach, ensuring food security and fostering informal income generation within migrant communities. According to David Crouch, while pastoral gardens are the product of the business or the state, the allotment is a working-class landscape for ordinary people [28]. It brings leisure and productivity together through vernacularity. Establishing one’s roots through gardening takes on a crucial meaning when the gardener is non-native.

A reference for non-intrusive design for the architecture is Treist Plein (Figure 31), the renovation of the abandoned mental ward in Melle, Belgium, by Architen de vylder vinck tallies (advvt). In terms of this thesis scope, interventions to promote trauma healing alludes to more gentler approaches. Through the agency of the built spaces, the public can offer leniency to allow tension to gradually relieve itself, leading to a new wave of healthier minds and bodies that can be more accepting of themselves [29] .

Therefore, gardening and ownership over a self-curated landscape mark the permanence of their livelihood in a new country. Furthermore, by embracing the quotidian nature of allotment design, the tired migrant bodies can start to heal through the freedom to nourish their traditional crop garden as a tangible product of their heritage. (Figure 07, p12)

27. Patrick Flannery Walker, “Soil Rises,” Patrick Flannery Walker, 2021, https://www.patrickflannerywalker.com/soil-rises#1, 1m30s.

28. David Crouch, “The Allotment, Landscape and Locality: Ways of Seeing Landscape and Culture,” Area 21 3 (September 1989): pp. 216-267, https://doi.org/http://www.jstor.org/stable/20002756, 217.

29. Bart Decroos and Gideon Boie, “Designing Your Symptom: Expanding Architecture in the Context of Mental Health Care.,” in Unless Ever People (Antwerp: Flanders Architecture Institute, 2018), pp. 186-219.

08. ETHNOGRAPHIC RESEARCH

The objective of this research method was to unravel the intricacies of the city and comprehend the intricate tapestry of its migrant community. This journey spanned a multitude of interviews, both formal and informal, each contributing to a nuanced understanding of the urban landscape and its diverse inhabitants. Serendipitous encounters with key personalities became pivotal, providing invaluable guidance in shaping the trajectory of my design and research endeavors.

Migrating gardens within Torcy's allotment — on the Eastern edge of Torcy (Figure 09, p14), the study revealed a significant locus, the town's community allotment (Association Les Jardins Familiaux), comprising 105 gardening lots (Figure 34). Amidst this allotment, the presence of migrating gardens materializes as a testament to its multifaceted nature. A poignant instance unfolds through the narrative of a Vietnamese gardener whose 200 kilos of wintermelon attest to the thriving yields from her garden, emblematic of the coalescence of cultures within this space [30]. This bountiful harvest came from Ms. Ninh's Vietnamese vegetable garden (Figure 32 & 33). Engaging in a conversation with her shed light on the multifaceted benefits of gardening that was theorized and researched in the previous section this thesis. It became apparent that the act of gardening transcends mere seed planting; it forms the cornerstone of a social ethos, allows migrant bodies to connect with their roots through migrating seeds, and fosters a symbiotic network that unites individuals from disparate backgrounds.

Among the gardeners, there exists a culture of sharing knowledge and harvests, wherein the purpose of cultivation extends beyond the yield to encompass mental and physical well-being. There are also collective efforts among gardeners to maintain a

communal ground in order to fosters impromptu social interactions. While the spatial remoteness of the allotment from the town center stands as a limiting factor, the allotment becomes a remote community of its own with full mobility, nevertheless, it is detached from the urban fabric of Torcy.

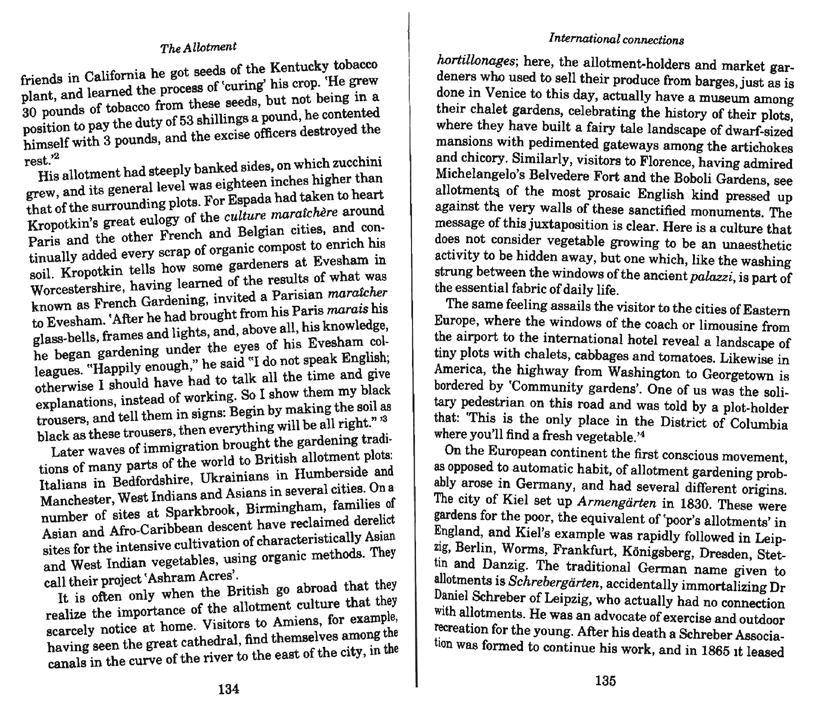

Desires for a migrating garden — In the trajectory of Torcy's evolution from the refugee crisis to the present, the town emerged as a hub for migrant families, especially with newcomers from non-former colonies such as Peru, Thailand or Sri Lanka [31]. In

the to deepen the insights into the aspirations and necessities of individuals regarding their prospective migrating gardens, an interactive workshop was held during a French language class. The attendees, despite being identified in this research as "students," were predominantly working adults, ranging from their thirties to fifties. The workshop, conducted in March 2023, encompassed a diverse group whose resettlement in Torcy spanned between three months and eighteen years. The candidness and depth of their responses resonated with a profound desire for migrating gardens, coupled with a shared yearning for a communal space to exchange cultivation knowledge and experiences among fellow gardeners.

However, a critical revelation emerged from their narratives: the challenge faced by migrant individuals in reconciling their work commitments with the nurturing of a garden. This struggle is palpable among recent arrivals who express the desire for a garden yet hesitate to initiate one due to their substantial work responsibilities. Despite this hurdle, the participants demonstrated resilience by offering potential solutions. These included the proposition for a garden conveniently located within walking distance from the OMAC (Municipal Animation and Culture Office), ensuring easy accessibility. Additionally, they envisioned a climate-controlled greenhouse as a practical solution, catering to their aspirations to cultivate tropical nonnative seeds in an accommodating environment.

Reality of the migrant families gathering space — However, an evident gap in social support mechanisms prevails, encapsulated within the limitations faced by the Community Animation Center (OMAC), striving to host activities for the growing migrant populace, albeit constrained by meager subsidies. The center is

positioned on the left side of the affordable housing block, erected in the 1970s in order to accommodate the incoming refugees (Figure 09, p14). This was also Mr. Tiến's family first place of residence in Torcy. Surrounding a public plaza is a cluster of building that support the OMAC programs, including a music hall, swimming pool, language class, and migrant family resources.

While its location is at walking and biking proximity, accessing this community hub become challenging due to unexpected turns and difficult wayfinding (Figure 39)

With the entrance points being hard to access, its prime location in the town becomes obsoclete, especially when this a main resource point for the most vulnerable community in Torcy. Moreover, the lack of awareness and subsidies are faced by working staff like Bakary (Figure 42). He is a young migrant from Senegal who used to take French language classes at the OMAC, now working as a language at the center, highlights the discrepancy between the aspirations of fostering social engagement and the practicalities of the available resources, contribute his own money and hours trying to bridge this gap:

I was once also a student in these language classes, so I want to give back to the community that support me, even when the work is unpaid. My main job is the coach for the OMAC youth football FC. I love working with young people, but I often have to pay for the supplies myself because there’s very little funding. [32]

This issue runs deeper. Going back to the infrastructure, in 2015, the OMAC envisioned a vibrant plaza, under a canopy, as a main gathering point for kids and migrant families, as well as a cohesive interconnection between their facilities (Figure 40). However, this hopeful project remains eclipsed by the stark reality—a mere parking lot (Figure 41). This disparity between vision and actuality underscores the palpable challenges in realizing communal spaces conducive to fostering diverse interactions and engagement among migrant communities.

The identified issues arising from the suboptimal positioning of the allotment, constrained financial resources, and the unfortunate state of the community animation plaza highlight the challenges faced by Torcy in adequately caring to its migrant population. While

foundational efforts for the migrant population exists, a common issue remains where it is only bare minimum, and the situation underscores a marginalized status of the available social provisions, which are perceived as peripheral to the Torcy's main social agenda. These observations suggest a lack of attention directed towards addressing the needs of the Torcy's migrant community. The existing social amenities meant for the them are relegated to peripheral considerations, underscoring an urgent need for a robust effort to improve the existing frameworks that are meant for the migrant communities within Torcy's social fabric.

09. EDGE CONDITION & DESIGN SITE

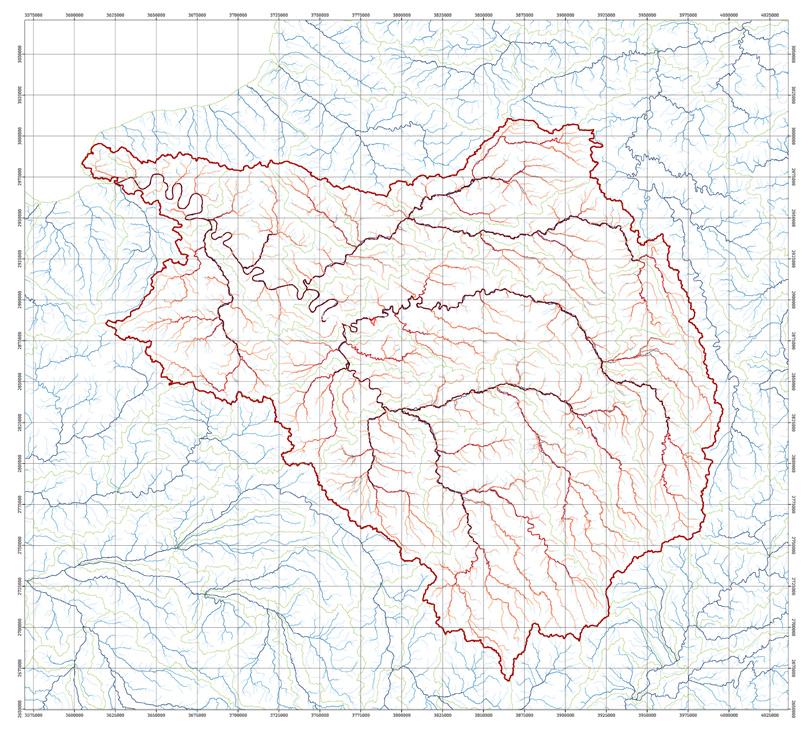

Seine Waterw Basin — this relationship holds pivotal significance in understanding the town's periphery and the location of the proposal of a Migrant Archipelago. First of all, an overview of the European river network of Europe unveils the fascinating formation of river basins that transcend human-made borders, with one basin crossing through France, Belgium and Netherlands (Figure 43). In a metaphorical sense, the organic creation of a basin echoes the inherent conflict between the imposed limitations and societal constructs imposed on the organic flow of natural streams. This narrative often parallels the diverse routes taken by refugees and migrants during their diasporic journeys.

Focusing on the Seine River basin (Figure 44), named after the primary drainage stream, spanning 754 kilometers in length, traverses significant urban centers across France, commencing its journey close to Dijon, coursing through the heart of Paris, and ultimately discharge into the English Channel. The expansive drainage area of its basin spans approximately 75,976 square kilometers. Within this watershed, the average recorded rainfall stands at 666 mm annually. This vital river basin serves a populace exceeding 16.5 million residents [33]. The Marne's sub-basins are part of this intricate network, with Torcy (blue) and its references (yellow) highlighted to concentrate on the important sector of the Marne.

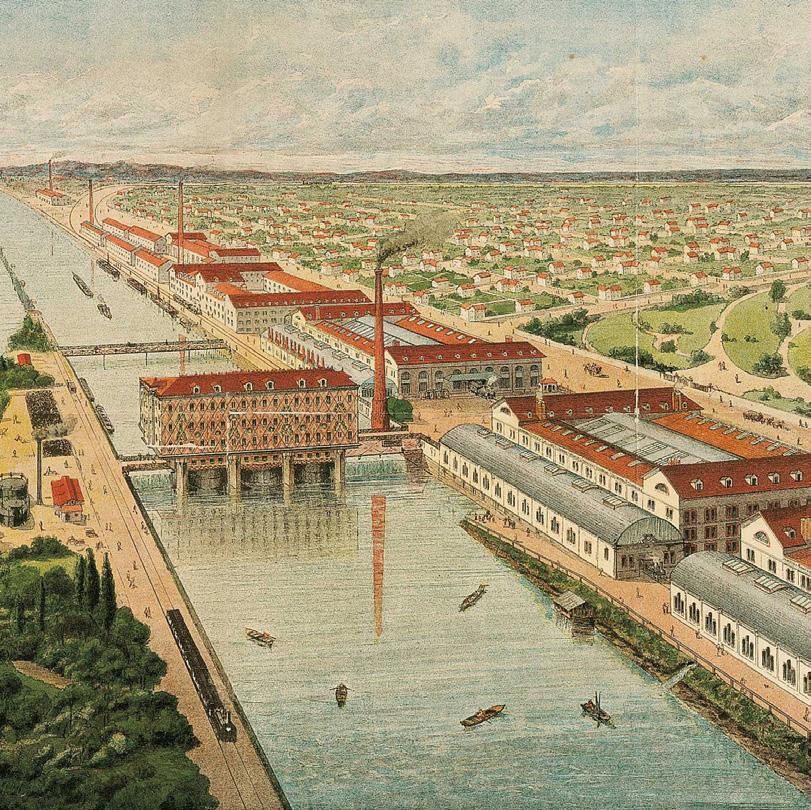

Menier Chocolate and the Marne — a historical narrative intertwines with this specific river culture. The French chocolate company Menier, previously established as the sponsor for the greenhouses within the Colonial Jardin [34], planted its legacy along the Marne river edge in Noisiel, on the western border of Torcy. During the 18th century, there were no inherent borders between the two villages. In 1825, the company's founder amalgamated three river islands to craft a chocolate empire (Figure 45). The Menier family gradually expanded their industrial estate from Noisiel into Torcy river edge, assuming their dominance in not only the chocolate world, but also the lasting river relationship of these two towns. Therefore, by the end of the 19th century, it covered some 1,500 hectares, spread over Noisiel and Torcy (Figure 46). The "Domaine de Noisiel", organized around the Ferme du Buisson, includes farmland, beet fields, natural meadows, osier groves, parks and a stud farm [35]. By the 1900s, Menier's prowess in chocolate production peaked, boasting an annual output of a staggering four thousand tons, harnessing hydraulic power from the river dam. While Paris was the French metropolitan capital, the Menier chose Noisiel and Torcy to expand their chocolate business, thus, putting these pastoral villages onto the industrial map.

The employees of the Menier company, dwelling in both Noisiel and Torcy townships, engaged in a serendipitous weekend river culture in recreational and leisure pursuits such as biking, canoeing, and kayaking. This picturesque setting also served as a backdrop for domestic chores. Despite the industrialization that accompanied the Menier's presence, the local residents persisted in their customary leisurely engagements along the river, maintaining a semblance of ordinary recreational activities. (Figure 47)

34. Refer to Part 07 - Migrating gardens - A product of colonialism.

35. “Les Menier, Une Dynastie Industrielle,” Archives Department of Seine-et-Marne, 2015, https://archives.seine-et-marne.fr/fr/ menier.

Figure 45. In 1825, Noisiel and Torcy were among the small villages by the Marne. Since 1825, with the Menier planting their headquarter and factory here, the river culture altered completely. Noisiel became a company town for Menier. Because of their close location, Torcy became a proxy company town to the Menier workers (Source: Archive Department of Seine-et-Marne)

Fading river culture — However, the refugee crisis marked a pivotal shift, precipitating a decline in Torcy's river-centric culture. With a massive population surge, the Torcy municipality found solution in affordable housing for the newcomers. Gradually, the town distanced itself from the riverfront. Additionally, due to being inside a river basin, the great difference between the hill and the valley made it challenging for the town to comprehensively plan its urban fabric (Figure 48). Therefore, Torcy's past as a river town has departed from the Marne, and grow deeper inland. In 1978, the Île-de-France government made some efforts to rejuvenate the river culture with projects centered around leisure tourism, culminating in the creation of joint leisure islands (L’île De Loisirs) of Vaires-Torcy [36] . A strategic planning to attract more visitors while they travel between Paris and Disneyland, these suburban town has been turned into a destination for touristic consumption more than for the benefits of the residents of this town. (Figure 50)

The 2024 Paris Olympics — The looming specter of tourism-led capitalism further transformed the landscape. The impending 2024 Paris Olympic is taking place within the leisure islands, resulted in the construction of a state-of-the-art canoe and kayak whitewater stadium called the Stade Nautique Olympique (Figure 51). Finished in 2023, will be used for the canoe and kayak competitions, and subsequently, will be used by the surrounding towns for high-level athletes or sports enthusiasts. Once again, there will be a spike in Torcy's population in the foreseeable future from the Olympics the river's landscape primarily for commercial gains rather than catering to the needs and aspirations of local residents. The dominance of the Olympic grounds redefined the river's character, symbolizing a departure from its historical significance

36. Récréa, “L’île De Loisirs De Vaires-Torcy,” Region Île-deFrance, 1978, https://vaires-torcy.iledeloisirs.fr/.

towards a landscape sculpted by profit-driven motives. The Olympics, with their grandeur and global attention, have the potential to inject substantial wealth into a town or city by attracting investments, tourism, and infrastructure improvements.

For instance, the 2012 London Olympics brought in a surge in economic activity, with increased tourism, job creation, and infrastructure enhancements such as new venues, transport upgrades, and urban regeneration projects. These developments initially offered promises of economic growth and rejuvenation for several neighborhoods in the outskirt area of the city. While it can generate wealth and opportunities, it also exacerbate social and economic disparities within a town or city. London's Olympic legacy revealed a mixed picture of outcomes. Despite the improvements made, some areas experienced rapid gentrification, leading to increased property prices, pushing out longtime residents, and changing the social fabric of these neighborhoods. Petty crimes and disparities often occur in the peripheral of a Olympicification area [37]. Furthermore, the investments primarily concentrated on specific areas hosting the games, neglecting other parts of the city. This skewed focus led to widening socio-economic disparities, as the benefits of the Olympics weren't evenly distributed across all communities [38]. The initial interest and economic boom surrounding the event often faded post-Olympics, leaving certain areas without long-term sustainable improvements.

In summary, while the Olympics can bring prosperity and development to a town, it also has the potential to deepen existing inequalities by favoring certain regions or communities over others, which demands a balanced approach in planning and development to ensure inclusive growth and benefits for all residents.

37. Barrie Houlihan and Richard` Giulianotti, “Politics and the London 2012 Olympics: The (in)Security Games,” International Affairs 88, no. 4 (2012): 701–17, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.14682346.2012.01097.x, 712.

38.Peter Bishop and Lesley Williams, eds., “Design for London: Experiments in Urban Thinking,” Experiments in Urban Thinking, 2020, 170–214, 175.

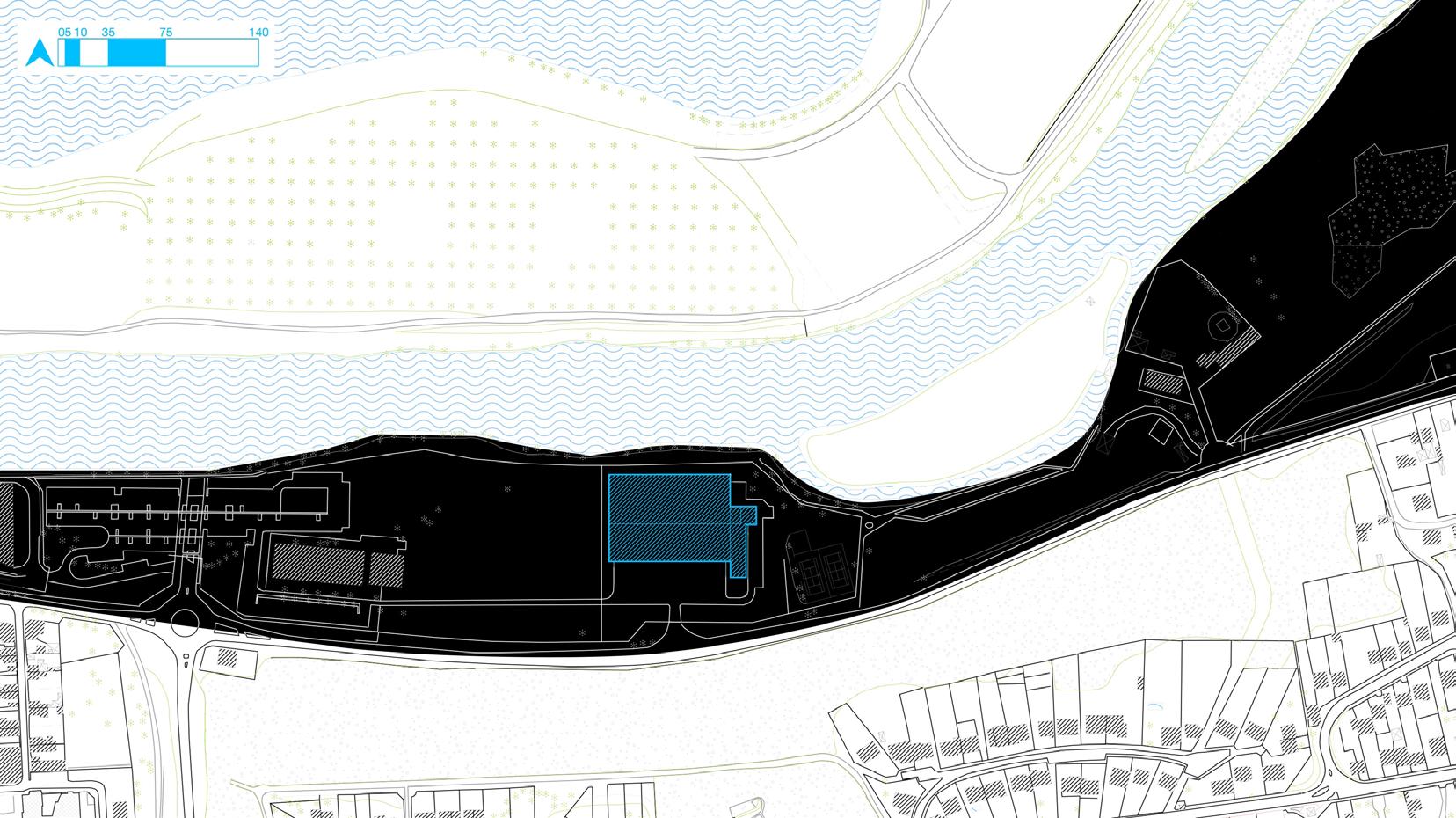

Introducing the design site — Upon the first glance, Torcy's river edge seems unbothered and peaceful, however, through serious investigation, there are various evidences of neo-colonialism and capitalistic tourism occupying the river culture. It is clear that the design proposal is destined planting its roots at the center of this river landscape, where there is one place left that is left behind through all of the changes. It takes shape as a warehouse that once belonged to none other than the Menier factory (Figure 50). With further groundwork, the warehouse physical site and historical context speak with volume for an intervention, especially within its new identity as an Olympicification area. The warehouse, serving as the locus of this endeavor, stands in a unique setting – an isolated position along the river's edge, reflecting a deeper connection to the area's heritage, and notably linked to the Menier.

Erected in the year 1978, this expansive structure spanning 84x60 meters served as the final expansion to the Menier enterprise. Its primary role was to serve as a frozen storage unit, managing the surplus chocolate inventory for the company. Nevertheless, the trajectory of the factory altered following its transition into Nestle's ownership in 1990, marking the cessation of its production (Figure 49). The Menier main facilities became offices and heritage buildings, while the warehouse was gated away from the rest as it was not considered for the UNESCO heritage (Figure 55). By its form, it is merely an industrial shed, while other Menier buildings were built with a combination of the architectural style of the end of the 19th century and industrial functionality [39] . Consequently, this pivotal shift led to the abandonment of the warehouse, remaining neglected and unattended for an extensive duration of three decades until its acquisition in 2020 by Aspasia, a distributor specializing in pre-packaged Asian food products.

39. “Les Menier, Une Dynastie Industrielle,” Archives Department of Seine-et-Marne, 2015.

Under the new ownership, incremental improvements were introduced to the warehouse to restore its functionality, including facade refurbishment, excavation for loading docks, and the installation of new fences, marking a transition from neglect to resurgence in the structure's utility. (Figure 53)

Contrary to the warehouse's secluded nature, the Marne riverbank revealed to be quite active. Even though the town transitions inward, people still find their ways to the riverbank and enjoy various leisure sports and activities there (Figure 54). Through personal observation on-site, the beaten path is well-used, regardless of its uneven terrain. People find ways to frequently cycle or walk along the Menier river dam, and the journey can be extended even further to Paris for the more adventurous. The Marne's riparian edge shows signs of other non-native species such as the Canadian pines and the Norwegian maple trees, reaffirming the natural trajectory of inevitable migration that happens when human travel and experiment with flora. This riverbank is accessible by various means—vehicles, public transport, or a picturesque forest pathway, frequented by residents of Torcy and Noisiel.

The warehouse as the site of design — Similar to the missing puzzle, this warehouse anonymity towards its surrounding becomes a new challenge that compliments well with the motivation of this thesis, which is to bring a sense of belongings to peripheral bodies. Located between the Menier and the Olympics, these giants are transforming the riverside into a mecca of tourism, even though the promise was for the local residents. Therefore, the design approach here wants to remain gentle, approachable, and for the local residents, which also includes the existing migrant community. Thanks to the universal design of this warehouse, intervention can be made according to the existing structural grid remain In terms of circulation, the approach

towards the site through the forest presents a gradual unveiling of the greenhouses, offering a fulfilling arrival experience, despite the challenging downhill slope. The circulation strategy interweaves the context through two main arteries—one traversing the landscape and one through the interior. This cohesive circulation scheme seeks to meld diverse elements and create an integrated environment.

In the scope of contemporary France, the migrating gardens and their diasporic cultivator resonates profoundly. This narrative unfolds within the shifting societal lens, evolving from a perspective that objectified 'exotic' elements to the contemporary lexicon, characterized by terms such as 'foreign,' 'other,' or 'invasive.' These altered perceptions complicate the process of migrant communities establishing firm roots and finding resonance in their new environment. An imperative within this research endeavor lies in the consolidation of these findings into a design framework. The aim is to leverage the inherent strengths and distinct advantages of both spaces—the allotment and the plaza.

DESIGN TERMS

10. DESIGN TERMS & CONCLUSION

By discerning from their respective shortcomings and failures, the goal is to forge a unified, inclusive platform. Such an amalgamation aims not only to facilitate the healing and celebration of migrant cultures but also to restore unity and integrity to the town of Torcy. This process seeks to foster a comprehensive and harmonious communal space that accommodates diverse cultures while revitalizing Torcy's collective identity.

In terms of a designing process, the first question is: What is it? — It is a place suitable for an allotment garden for migrating people and their seeds, with a controlled environment for these seeds to grow and prosper. It is also where seeds can be reserved for new comers to start their own garden, maintaining the longevity of the project incrementally through time. Ideally, it is a place to help generate micro-income and healthy produces for its users/gardeners/visitors. And there is rooms for people to gather, relax and exchange not only their harvest, but also meaningful cultural motives.

Reflecting back to the primary research question

How does a productive garden serve as a regenerative therapeutic space for the migrant community in Torcy and its surrounding areas to reconnect with their cultural roots? The research body's central core of evolves around crafting an inclusive, secure, and respectful space in Torcy, conceptualized to embrace and support migrating gardens and their associated entities. Termed as the "Migrant Archipelago," this envisioned platform aims to serve as a pivotal design construct, fostering an environment conducive to the cultivation and sustenance of these diverse, culturally resonant gardens.

This design synthesis aims to explore the transformative potential of productive gardens by the Marne, on the

edge of Torcy, dissecting their role as regenerative and therapeutic / healing spaces that facilitate a profound reconnection for the migrant community with their cultural heritage and roots (Figure 56).

In light of the warehouse's history and its proximity to riverfront "giants" like those associated with Menier and the upcoming Olympics, the focus of this new public interior aims to rejuvenate a sense of belonging, particularly in the town's overlooked peripheries, for the people of Torcy and the neighboring towns. The purpose of this design proposal is twofold: to reorient Torcy's orientation toward the Marne River to revive engagement with the overlooked edge of the town and perform as a space for migrant bodies to find solace in healing through productive gardening. The design components include:

– An allotment of migrating gardens

– A market hall

– A seed bank

– A cultivation lab

The programs empower the autonomy and resiliency of those with refugeehood and migrant background, and at the same time, making room to materialize people’s cultural identity with unique products from gardening. The archipelago can maintain its longevity through the bank of non-native seeds and educational program to enrich and connect the youths and young adults of Torcy to more interactions with a productive green space. This design co-exist alongside with the Aspasia operation. While the warehouse is currently in use, based on its frequent usage of the new loading dock, the design inhabits the left side and extending into the exterior ground. (Figure 57)

Specific programming — Through extensive research on Torcy peripheries, a synthesis of essential programs has been developed for the scheme (Figure 60). Their organizations aims to encapsulate and honor the heritage values of migrant culture through productive gardening, manifesting as two distinct typologies: the greenhouse, acting as a research lab, and the allotment. Moreover, the sustainability and durability of this initiative hinge on three pillars: income generation, knowledge sharing, and fostering conviviality, which are manifested through a market hall, consisted of the market, the resource center, and skill-based workshops

Catering to users spanning from short-term to longterm residents, these programs additionally strive to ensure food security for newly settled migrants. The strategic allocation of programs is meticulously based on the spatial requisites and climate suitability of the site, adapting to the existing spatial quality. This entails a height variation from 7 to 12 meters to suit the proposed programs effectively. Additionally, the research lab takes shape as sunken greenhouses in the loading dock area, following the same building technique as the colonial greenhouse to optimize thermal heat mass. (Figure 27 & 28, p23)

Furthermore, the division of the site follows a defined rule: the southern half, oriented towards the street, is dedicated to productive and gardening programs, while the northern half, facing the river, is allocated for social and leisure programs. (Figure 59)

To secure the proposal's economic viability, a phased approach of incremental additions has been chosen. Modular structures designed for reusability and upcycling, coupled with collective maintenance efforts by the users, ensure sustainable development. This incremental design strategy disaggregates large-scale

projects into affordable and manageable improvements, targeting both landscape and interior spaces, including modifications to facades and roofs. (Figure 59)

Conclusion — This study delves deep into the layered hardships experienced across generations by migrants, offering a compelling proposition – an active archipelago as a responsive solution. While archipelagic thinking is a non-physical landscape, by recognizing its existence, it can be realized into a tangible landscape. The outcomes of the program entail a pivotal space where the act of harvesting, sharing, and preserving tangible heritage finds its essence. By integrating productive gardens and acknowledging their societal values, this project serves as a catalyst in healing the invisible wounds of diaspora. The core of this design research revolves around establishing a symbiotic relationship between productivity and leisure. This convergence births an archipelago of regenerative spaces, a gentle intervention for Torcy, reconstituting the town's unity and completeness. (Figure 58)

Moreover, this design endeavor is a haven where the peripheral bodies of Torcy discover empowerment, highlighting their inherent strength in social and healing capacities, especially in the allotment culture and tending a garden. It becomes a secure realm for reclaiming autonomy, embedding within the history and culture that have often overlooked them.

It's crucial to note that migration continues to be an ongoing narrative. This archipelago acts as a catalyst, reinstating Torcy's connection to the river, fostering healing within the existing migrant community, and ensuring a sustainable legacy for future generations of migrant bodies. It is also a matter of re-territorialization of the peripheral bodies. [40]

The city is an artifact filled with ideas, hopes, and dreams from its people. In exceptional circumstances such as that experienced refugeehood, the architecture of the place people chose to settle down was not the priority, but rather, recreating and tracing back to how their familiarities are the beginning of creating a “home”. The project harness the healing capacity of green space and social quality of gardening together to host a green archipelago by the Marne River. Through meticulous incremental additions and modifications to the warehouse infrastructure and its surroundings, these peripheries collectively converge into a re-imagined and purposeful landscape—the Migrant Archipelago.

40. Rob Shields, “Review: Contemporary Archipelagic Thinking: Toward New Comparative Methodologies and Disciplinary Formations. ,” SPACE AND CULTURE, November 28, 2020, https://www.spaceandculture.com/2020/11/28/reviewcontemporary-archipelagic-thinking/.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

00. BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alessandrini, Kyra. “Lieux Oubliés: Les Vestiges Des Expositions Coloniales Au Bois de Vincennes.” RFI, August 21, 2018. https://www.rfi.fr/fr/france/20180820-lieuxoublies-vestiges-expositions-coloniales-bois-vincennes.

Atherton, James. “Planting Seeds in Refugee Camps.” Regenerosity, August 20, 2020. https://www.regenerosity.world/stories/planting-seeds-in-refugee-camps.

Bishop, Peter, and Lesley Williams, eds. “Design for London: Experiments in Urban Thinking.” Experiments in Urban Thinking, 2020, 170–214.

Chung, Tiffany. “Vietnam, Past Is Prologue.” James Dicke Contemporary Artist Lecture. Lecture presented at the James Dicke Contemporary Artist Lecture, May 2, 2019.

Crouch, David, and Colin Ward. The allotment: Its landscape and culture. Nottingham: Five Leaves Publications, 1994.

Crouch, David. “The Allotment, Landscape and Locality: Ways of Seeing Landscape and Culture.” Area 21 3 (September 1989): 216–67. https://doi.org/http://www.jstor. org/stable/20002756.

Decroos, Bart, and Gideon Boie. “Designing Your Symptom: Expanding Architecture in the Context of Mental Health Care.” Essay. In Unless Ever People, 186–219. Antwerp: Flanders Architecture Institute, 2018.

Findeisen, Władysław, and E. S. Quade. Essay. In The Method of Applied Systems Analysis: Finding a Solution, 117–49. Laxenburg, Austria: International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis, 1980.

Gandhi, Envyn Lê Espiritu. Archipelago of resettlement Vietnamese refugee settlers and decolonization across Guam and Israel-Palestine. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2022.

Garnier, Josette, Juliette Anglade, Marie Benoit, Gilles Billen, Thomas Puech, Antsiva Ramarson, Paul Passy, et al. “Reconnecting Crop and Cattle Farming to Reduce Nitrogen Losses to River Water of an Intensive Agricultural Catchment (Seine Basin, France): Past, Present and Future.” Environmental Science and Policy 63 (2016): 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.04.019.

Hacquemand, Eric. “La Communauté Asiatique Met Le Cap à l’est.” leparisien.fr, January 27, 2001.

https://www.leparisien.fr/seine-et-marne-77/la-communaute-asiatique-met-lecap-a-l-est-27-01-2001-2001917516.php.

Hartwig, Kari A., and Meghan Mason. “Community Gardens for Refugee and Immigrant Communities as a Means of Health Promotion.” Journal of Community Health 41, no. 6 (2016): 1153–59.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-016-0195-5.

Hein, Jeremy. “Refugees, Immigrants, and the State.” Annual Review of Sociology 19, no. 1 (1993): 43–59.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.19.080193.000355.

Hirsch, Marianne, and Marianne Hirsch. “Postmemory’s Archival Turn.” Essay. In The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust, 277–250. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Houlihan, Barrie, and Richard Giulianotti. “Politics and the London 2012 Olympics: The (in)Security Games.” International Affairs 88, no. 4 (2012): 701–17. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1468-2346.2012.01097.x.

Lambert, Léopold. “Diasporas - Introduction.” The Funambulist: Politics of Space and Bodies no. 43, September 2022.

“Les Menier, Une Dynastie Industrielle.” Archives Department of Seine-et-Marne, 2015. https://archives.seine-et-marne.fr/fr/menier.

Lê, Tuyen. A Conversation with Mr. Tiến . Personal, March 17, 2023.

Lê, Tuyen. Conversation with Ninh Bùi. Personal, March 28, 2023.

Lê, Tuyen. Conversation with Tuấn Mami. Personal, February 27, 2023.

Lê, Tuyen. Interview with Bakary and Dieynaba. Personal, April 6, 2023.

Lê, Tuyen. Workshop with the OMAC language students. Personal, March 28, 2023.

Mark, Pimlott. “About Looking.” Interiors Buildings Cities Lecture. Lecture presented at the Interiors Buildings Cities Lecture, September 23, 2021.

Mauduit, Xavier. “Épisode 3/4 : La Colonisation Par La Racine.” Le Cours de l’histoire Podcast, September 11, 2019. https://www.radiofrance.fr/franceculture/podcasts/ le-cours-de-l-histoire/la-colonisation-par-la-racine-5430275.

Meunier, Phillip, ed. “Catalogue Des Ouvrages Sur Les Cultures Tropicales et Les Productions Des Colonies.” Essay. In Exposition Coloniale Nationale de 1907 : Guide Officiel et Catalogue Général, 100–170. Paris: P. Meunier, 1907. Millican, Juliet, Carrie Perkins, and Andrew Adam-Bradford. “Gardening in Displacement: The Benefits of Cultivating in Crisis.” Journal of Refugee Studies 32, no. 3 (2018): 351–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fey033.

Nèves, Corinne. “Voyagez Dans Le Temps Au Jardin d’agronomie Tropicale Du Bois de Vincennes.” Le Parisien, July 27, 2020. https://www.leparisien.fr/culture-loisirs/ sortir-region-parisienne/voyagez-dans-le-temps-au-jardin-d-agronomie-tropicale-dubois-de-vincennes-27-07-2020-8359443.php.

Odile, Rouhban, and Tanneau Pierre. “Immigrants and Descendants of Immigrants.” Insee, April 11, 2023.

https://www.insee.fr/en/statistiques/7342924?sommaire=7344042.

OECD. “Trends in International Migration 1997.” Trends in International Migration, 1997, 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-1997-en.

Red, Raphaëlle. “Sites of Diaspora Include.” The Funambulist: Politics of Space and Bodies 43, September 2022.

Récréa. “L’île De Loisirs De Vaires-Torcy.” Region Île-de-France, 1978. https://vaires-torcy. iledeloisirs.fr/.