Hudson River & Delaware Valley

Selections from the Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection and the Mark Biedlingmaier Collection

Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Mark Biedlingmaier

Darlene Miller-Lanning

Carol Maculloch

Hudson River & Delaware Valley

Selections from the Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection and the Mark Biedlingmaier Collection

Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Mark Biedlingmaier

Darlene Miller-Lanning Carol Maculloch

The Hope Horn Gallery The University of Scranton

October 21 through November 22, 2024 February 3 through March 14, 2025

James Hope (1818-1892). Rainbow Falls. Watkins Glen. Oil on panel. 1871. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

3

Dedication

Amy Biedlingmaier Brown

Paul Biedlingmaier Jr.

Mark Biedlingmaier

t 5

Acknowledgements

Darlene Miller-Lanning

Carol Maculloch

G 7

An Interview with the Collectors

Paul Biedlingmaier Jr.

Mark Biedlingmaier

Darlene Miller-Lanning

t 13

An Overview of the Collections

Paul Biedlingmaier Jr.

Mark Biedlingmaier

Darlene Miller-Lanning

G 66 Notes

Thomas Hill (1829-1908). View on the Hudson River. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

Thomas Griffin (1858-1918). The Delaware Water Gap. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Mark Biedlingmaier Collection.

Dedication

Dr. Paul Biedlingmaier (1924-1993)

Mrs. Romaine Lenherr Biedlingmaier (1925-2024)

This catalogue is dedicated to our beloved parents. They served as guiding beacons for our family and instilled in us an appreciation for nature that inspires our life and our art.

Amy Biedlingmaier Brown, Marywood University ’75

Paul Biedlingmaier Jr., The University of Scranton ’76

Mark Biedlingmaier, The University of Scranton ’80

Guy Carleton Wiggins (1883-1962). Wall Street. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

Acknowledgements

In Fall 2024 and Spring 2025, the Hope Horn Gallery at The University of Scranton is pleased to present the two-part exhibition and catalogue project Hudson River and Delaware Valley: Selections from the Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection and the Mark Biedlingmaier Collection.

The Biedlingmaiers are brothers, born and raised in Easton, Pennsylvania, yet linked to the city of Scranton through family ties and their education at The University of Scranton. Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. ’76 received his Bachelor of Arts in Finance and established a practice as a financial planner. Mark Biedlingmaier ’80 earned his Bachelor of Arts in International Affairs and Master of Arts in History and pursued a career as an international diplomat.

They are also art collectors. Inspired by personal connections to watersheds of the Hudson, Delaware, Lehigh, and Lackawanna Rivers, the Biedlingmaiers have gathered together American landscape paintings related to these regions for over forty years. Paul admires nineteenth-century painters affiliated with the Hudson River School, while Mark appreciates twentieth-century artists working in the Delaware Valley Region.

Deeply committed to The Royal Fund, The President’s Business Council, and The Michael DeMichele, Ph.D. ’63 Endowed Scholarship, the Biedlingmaiers have consistently supported their alma mater since graduation. Paul has served as a Chair of the Royal Fund, and Mark has received the Frank J. O’Hara Distinguished Alumni Award. In keeping with this long legacy of active engagement at The University of Scranton, they have also generously agreed to lend their art collections for exhibitions at the Hope Horn Gallery.

While developing an art collection can be a labor of love, the process carries with it an acceptance of deep responsibility. Sharing an art collection with a gallery for public display further requires a significant commitment of time and attention, which the Biedlingmaiers have provided without hesitation. Art opens minds, transcends boundaries, and evokes transformational experiences that align beautifully with The University of Scranton’s educational mission as a Jesuit institution. It is a true pleasure to work with the Biedlingmaiers and a great privilege to present their collections to our campus and regional communities.

This project has been made possible through the support and expertise of many individuals. At The University of Scranton, we thank George Aulisio, Ph.D, Dean, Weinberg Memorial Library; Colleen Carter, Director of Creative & Production Services; Jason Thorne, Senior Graphic Designer; and Kayley LeFaiver, Freelance Designer; for their expertise in planning, designing, and publishing the catalogue.

Darlene Miller-Lanning, Ph.D Director, Hope Horn Gallery

The University of Scranton

Carol Maculloch, MBA, CRFE

Director of Leadership Gifts and Planned Giving, Office of Advancement

The University of Scranton

Romaine Lenherr Biedlingmaier with Children Paul Biedlingmaier Jr., Mark Biedlingmaier, and Amy Biedlingmaier Brown. 2005.

Dr. Ferdinand and Marie Biedlingmaier at Cottage in Gouldsboro, Pennsylvania. c. 1940.

The Retreat Biedlingmaier Cottage in Gouldsboro, Pennsylvania. 1932.

An Interview with the Collectors

Paul Biedlingmaier Jr.

Mark Biedlingmaier

Darlene Miller-Lanning

Over the past forty years, brothers Paul Biedlingmaier Jr., University of Scranton Class of 1976, and Mark Biedlingmaier, University of Scranton Class of 1980, have collected art. Of special interest to them are representations by artists and of regions associated with the Delaware Water Gap, a natural and cultural landmark signifying the intersection of terrain and commerce in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. The paired exhibitions and accompanying catalogue, Hudson River and Delaware Valley: Selections from the Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. and Mark Biedlingmaier Collections, highlight this theme.

DML: The title of our show, Hudson River and Delaware Valley, refers to art historical and social geographical considerations linked to your collections. The Hope Horn Gallery at The University of Scranton has presented exhibitions addressing the geography, history, and culture of northeastern Pennsylvania. Research from these projects suggests that relationships exist between regions identified with the Hudson, Delaware, Lehigh, and Lackawanna Rivers. The waterways are separate; only two actually meet. But all have adjacent watersheds. The Delaware Water Gap marks the intersection of these areas, which are broadly associated with the Northeast Corridor. It anchors them, with the Hudson to the East, the Delaware to the South, the Lehigh to the West, and the Lackawanna to the North. Do you have a personal sense of those regional connections?

PPB: There is a connection between my cabin in Wayne County, nestled near Gouldsboro in the Pocono Mountains, and my house in Northampton County, located in downtown Easton at the confluence of the Lehigh and Delaware Rivers. The amazing thing is that the cabin is on Pocono Peak Lake and the natural springs are the source of the Lehigh River. It begins in those headwaters and passes through beautiful country in Monroe and Carbon Counties. Then, the Lehigh River ends in Easton, where it meets the Delaware. I grew up in Easton, and after years of traveling, I returned and have a house there. I can look at the Lehigh River where it ends. Fifty-five miles north at my cabin in Gouldsboro, I can look at the dam on the lake and think, “Oh my God, this is the beginning of the Lehigh River.” I actually have a beginning and ending in two places where I have a family connection.

Our family roots in Scranton and Lackawanna County have been tied to these regions across five generations. Our great-grandparents came to Scranton from Germany during the nineteenth century, and the city was a melting pot of people and cultures because of the industrialization happening there. They settled in Southside and became involved with St. Mary of the Assumption Church. Our great-grandfather worked for the railroad as a machinist. Our paternal grandfather Ferdinand attended St. Thomas College, now The University of Scranton, became a dentist, and maintained a practice on Pittston Avenue for over fifty years. Back in the 1930s and 1940s, he operated a dental clinic near the train station in Gouldsboro one day a week. I’ve met residents in their eighties who remember his practice and weekly mass attendance at the quaint St. Rita’s Parish.

As German immigrants to the United States, our family had a cultural appreciation of scenic natural landscapes and so gravitated towards the Pocono Mountains. Our grandfather bought a cabin in Gouldsboro where everyone gathered for vacations and our father carried on that tradition with us. We continue to love the area.

Dad served in the United States Army and Navy during World War II and the Korean War, respectively, then trained as an oral and maxillofacial surgeon at Temple University in Philadelphia. He and Mom were married in Scranton in 1952, and he subsequently taught at the University of Virginia Medical College in Richmond. Our sister Amy was born there, and the family returned to Scranton for the holidays. On the way, Dad stopped in Philadelphia to visit Dr. John Cameron, who had directed his dental internship. On Cameron’s advice, he moved to Easton, as they were in need of oral surgeons there. Before buying a home, he stayed at the YMCA while Mom and Amy lived in Scranton. Every Friday he would drive to be with them for the weekend, and I was born in Scranton eleven months later.

In 1954 my parents bought a beautiful mica stone house in the College Hill section of Easton, and the family relocated there. Mark was born in Easton, as was our late brother Ronald. Growing up there is partly how we became involved in collecting art. Easton has a rich history. A nineteenth-century canal ran through it, and the Lehigh Valley was strongly connected with the lumbering, mining, and ice harvesting industries. The homes on College Hill near Lafayette College were eclectic in terms of architectural styles. Mom and Dad collected antiques, so we grew up with an appreciation of history and art. To this day those things are still important to me.

MJB: Dad might have entered into a dental practice in Scranton, but our grandfather encouraged him to look elsewhere for better economic, family, and community opportunities. So, Dad attended Temple University and would hitchhike from Scranton to Philadelphia. The midway point was Easton. The Delaware River flowed through its historic downtown, and there were lush green areas in College Hill. Dad felt these aspects made Easton an attractive and inviting place to raise a young family.

Dad was a busy professional, but he was also a great outdoorsman. There was a transition from the hectic life of Easton to a breath of fresh air in Gouldsboro, figuratively and literally. Dad sometimes took Wednesdays off and Mom said it was the happiest time when they would stay overnight in the country to go boating and hiking. We would come up on the weekends. As an adult, the story of my life in government service was to leave that comfortable and familiar environment, traveling hither and yon across the world. Still, I never felt more relaxed and at peace than when I would come back to recharge in the Poconos.

DML: The Biedlingmaiers have been connected to Scranton for generations, but you were both raised in Easton. Why did you decide to attend The University of Scranton?

PPB: We enjoyed growing up in Easton. Amy attended Saint Francis Academy in nearby Bethlehem, I went to Notre Dame High School, and Mark attended Easton High School. In considering colleges, The University of Scranton was always on the radar as a possibility. Scranton was our family hometown, and our grandfather graduated from St. Thomas College, now The University of Scranton, in 1912. Dad attended The University before entering military service in 1942. I continued this legacy and entered The University of Scranton in 1972. It became a family tradition.

Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Home in Easton, Pennsylvania. Exterior View. Digital photograph. 2024.

Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Home in Easton, Pennsylvania. Interior View. Digital photograph. 2024.

Jesuit education is supreme. I think the education of the whole person is essential. I earned my Bachelor of Arts in Finance and became a financial advisor, but I didn’t just go to The University of Scranton, take my business courses, and go out and set the world on fire. I was required to take humanities courses, including theology and philosophy. I also took electives in music appreciation and art history. Professor Carol Spain was my art history teacher. Oh my God. When she walked into class she was absolutely beautiful, with her hair swept around her head in a beehive fashion. She also wore a shawl, which seemed very artsy. These many years later, I realize now the tremendous impact she had on my life. That’s when I really became interested in art and architectural history.

MJB: I enrolled at The University of Scranton in 1976. During my junior year at Easton High School, I completed advanced placement classes, and so in my senior year needed only an English and a gym course to fulfill my graduation requirements. Instead, I applied to the Rotary exchange program and went to Sweden in 1975. The academics were rigorous, and I studied eleven subjects, including French, German, physics, math, and natural science. This plan backfired a bit as the Pennsylvania Department of Education did not accept my course credits from Sweden when I returned. Technically, I don’t have a high school diploma, which I laugh about now because I did eventually earn both a Bachelor of Arts in International Affairs and Master of Arts in History in addition to participating in the Special Jesuit Liberal Arts Program (SJLA) at The University of Scranton. I initially applied to five colleges. My academic grades and SAT scores were fine. Still, the first four institutions asked me to complete my senior year, then enroll for class in 1977, which was an unacceptable option for me.

We spoke to the admissions counselors at The University of Scranton, who said, “Mark, the academic work you did in Sweden supports your credentials, and we invite you to enter the Class of 1976.” Throwing caution to the wind, I thought, “Okay, perfect. A degree is better than no degree or waiting another year.” That brought me to The University of Scranton, which was a wonderful experience. I worked with Dr. Ellen Casey in the Honors Program, Dr. Michael DeMichele in the History Department, and Fr. Edward Gannon in the Special Jesuit Liberal Arts Program. I am an ardent supporter of The University, and now there is a sense of obligation to pay a debt of gratitude to this institution for having offered me this opportunity.

Dr. DeMichele took an intense interest in his students, and he opened a number of doors in my sophomore and junior years. I completed an internship on Capitol Hill in Washington D.C. and was one of the first students to major in International Affairs because he looked at my background and talked often with me about my career interests. I had been associated with Foreign Service and State Department officers and thought that was exactly what I’d like to do. In the late 1970s, the field of International Affairs was coming into its own. Dr. DeMichele said, “Mark, you have all the requisite characteristics and skills of a Renaissance individual.” I had experience with foreign languages, including Swedish from the Rotary exchange and French from high school in Easton. I participated in The University of Scranton’s Honors and Special Jesuit Liberal Arts Programs and completed my undergraduate coursework in History. At the master’s level, my classes were geared toward International Affairs. This combination of linguistic ability, overseas travel, and internship experience became part of the curriculum that eventually launched the International Affairs major, and I really have Dr. DeMichele to thank for that.

DML: How did you become interested in collecting art?

PPB: I’m very fortunate that I took art history courses at The University of Scranton in the first and second semesters of my senior year. During that period, Mark was a high school Rotary exchange student in Sweden. In December, my early graduation gift was an airline ticket to go and be with him for Christmas and New Year’s vacation. We spent the holidays together, then I borrowed his knapsack and toured Europe by train. In my first art history course, I had studied European art and architecture, and so was excited to see the Rembrandt paintings at the Mauritshuis in The Hague, and the Pantheon near the Forum in Rome. I spent days visiting unbelievable museums and beautiful buildings. This experience helped tremendously because when I returned to Scranton for my second art history course, I had actually seen some of the works we were discussing and had a better appreciation of what was taught in the classroom with Professor Spain.

About fifteen years ago I began seriously collecting art. I was especially attracted to the natural imagery found in nineteenth-century landscapes of the Hudson River School. Several well-known auction houses routinely offer fine oil paintings for sale. I have purchased choice pieces through Freeman’s in Philadelphia, which is a very

reputable establishment. There are online sites where I specifically search for Hudson River School paintings a few times a week and many listings appear. Some pieces were carried to places far from the Northeast Corridor as families moved to Florida or California, then decided to sell art they no longer wanted. I also gravitate toward the smaller auction houses in New York and keep in touch with local dealers near Bangor and Wind Gap.

Weekend auctions can be crowded, so I like the ones held on weeknights. You can often visit them and find a real diamond in the rough. With a little care, a damaged painting can be restored to beautiful condition. Cheryl Chase does our art restoration work. Mark and I were very fortunate to find her in the little town of Matamoras right off Route 6. Cheryl was trained by an expert art restorer, and her work is very meticulous and timeconsuming. She takes photographs documenting the restoration process and makes notes on the chemicals and procedures she used. Cheryl is also a good connection with the auction houses, and sometimes knows of collectors selling works by Hudson River School artists.

I’ve been fortunate enough to acquire paintings by Asher Brown Durand and Albert Bierstadt. I actually drove twelve hours to a little town outside of Cleveland, Ohio to pick up the Durand, which was definitely worth the trip. I’m kind of lucky now and I’m so excited I want to go out and buy more.

MJB: I first became interested in art during my sophomore year of high school. I was taking French, and at that time the teachers arranged a quick language-immersion trip abroad. Trips were usually done over the Easter holidays. We took ten days to visit Paris and the chateau country. In my junior year, I trailed along with the German Club on a similar immersion trip to Germany. Paul and I grew up in a household where Mom and Dad collected

Bill Cardoni. Mark Biedlingmaier Home in Dingmans Ferry, Pennsylvania. Exterior View. Digital photograph. 2024.

Bill Cardoni. Mark Biedlingmaier Home in Dingmans Ferry, Pennsylvania. Interior View. Digital photograph. 2024.

antiques, but I think those experiences in France and Germany truly sparked my interest in art. Of course, we went to some of the best museums in the world, so early in my adult life I had exposure to excellent examples of European art from the Renaissance through Modern periods.

Later, as a Peace Corps volunteer in South Korea, I was introduced to a completely different style of art. Eventually, as I worked and traveled in over seventy countries with the Department of State, I visited many of the world’s greatest museums and galleries and began purchasing small pieces to bring home.

Works by well-known artists command high prices, and I could not afford large ticket items. But I bought pieces that I enjoyed and appreciated art from diverse cultures. While my favorite works always seemed to be landscape paintings, I challenged myself to push the traditional boundaries of that stylistic category. I began purchasing paintings by twentieth century artists, and eventually gravitated towards works by Delaware Valley painters from the 1960s and 1970s. I bought many pieces from the Hartzell Auction Gallery in Bangor. They often organize benefit auctions and themed shows featuring works by women artists and regional painters. So, having seen great art from around the world, I was inspired to build my own collection in a unique way and push the limits of my comfort zone.

DML: There is an old approach to collecting, known as a cabinet of curiosities, through which a collector gathers and arranges works representing his or her interests in such a way that together, they become an ideological selfportrait of that person. How have you installed and interpreted your collections within the context of your homes and their locations?

PPB: After graduating from The University of Scranton, I relocated several times, pursuing career opportunities across the country. I lived and worked in Washington D.C.; Wilmington, Delaware; Salt Lake City, Utah; Atlanta, Georgia; and Lansdale, Pennsylvania. Once my children were grown, I came back to Easton. Returning to the city gave me the opportunity to see Mom more often. I bought the Clyde Bixler House, a Victorian home in downtown Easton. In the eighteenth century, the Bixlers were among the first jewelers and clockmakers in the United States. I restored much of the house to the original architecture and now call it home. Elizabeth Mitman, a local interior designer with family connections to the Bixlers, helped me with the restoration process. It’s exciting to be back in Easton, which was the foundation of my parents’ success. Owning a historic home in the city which I dearly love is a dream come true.

MJB: Paul’s historic townhouse in Easton complements his Hudson River School paintings. I knew he purchased art but didn’t realize the extent to which he was actively collecting masterworks by several top-tier painters. I am impressed by the quality of the works he has acquired, and how appropriately they are presented in the restored home, which dates from a similar time period, the mid-nineteenth century. I knew Paul had good taste, but I thought of him as an outdoorsman, and was shocked in a positive way to learn that he had such a fine eye for art and interior design. About ten years ago, in the midst of assignments in Afghanistan and Iraq, I began looking for property to purchase in Pennsylvania. I knew I wanted to settle there, and when I found a site in Dingmans Ferry (also on the Delaware River!) I knew that roots could be reestablished in that place. It’s not Easton. It’s not Gouldsboro. But it has many of those same familiar traits. I was inspired by Walden: the house I built carries a sense of peace, relaxation, and appreciation of nature. I have a feeling that’s why so much of my art reflects those particular traits and qualities. It is just a sort of an initial reaction. The house, in a sense, is also a cabinet of curiosities. When visitors come in, they often say, “Wow, Mark, this house is a reflection of your life.” When I built the house, I wanted to reflect my work and travels in spaces that would showcase my collection of American art as well as African masks, Russian icons, and Church and State items including historical documents and political posters. People seem to understand that, so those comments are taken as compliments.

Local art stager Dayne Altemose and auctioneer John Hartzell guided me to install the collection in the unique timber frame interior. When construction on the house was complete, I brought over the furniture, paintings, and artifacts that I had kept in storage for several decades. Dayne and I did a walkthrough, and I described to him what I wanted. Within two or three days, we put the house together. He had the eye for grouping paintings and arranging objects. He told me, “Mark, you have excellent material to work with,” but a lot of credit goes to him in terms of placement and creating a sense of the warmth and welcome rather than as a sterile museum setting.

Artist Unknown. Hudson River School Landscape. Oil on paper laid on board. Undated.

An Overview of the Collections

Paul Biedlingmaier Jr.

Mark Biedlingmaier

Darlene Miller-Lanning

In a conversation with Darlene Miller-Lanning, the Biedlingmaiers share insights related to their art collections. They explain their interest in Hudson River School painters Asher Brown Durand, Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Hill, and James Hope; family relationships between artists Julie Hart Beers, William Hart, Ralph Albert Blakelock, and Marian Blakelock; turn of the century New York City painters John Carleton Wiggins, Guy Carleton Wiggins, Johann Berthelsen, and Oswald Jackson; and Delaware Valley artists Owen Cullen Yates, Walter Emerson Baum, Sterling Strauser, and Justin McCarthy.

National Identities: Landscape Painting and the Hudson River School

DML: The Hudson River School of landscape painting was significant in American history and culture as it embodied a deep-rooted connection between the natural environment and national identity. Emerging in the early nineteenth century, it was also one of the first cohesive art movements in the United States, both related to and distinct from European artistic traditions. How did you become interested in this group of painters?

PPB: During my travels and studies, I gained an appreciation of art throughout the world, but really felt an affinity for American art, especially nineteenth-century landscape paintings connected to the eastern United States. I have strong family ties to the Scranton area and the geography there is familiar to me. I love the mountains. I love the outdoors. These things were central to Hudson River School artists, so I appreciate their work.

DML: In addition to documenting American scenes of nature, works by Hudson River School artists embodied characteristics associated with German Romantic landscape painting and the English philosophy of the sublime. As formulated by Edmund Burke (1729-1797), the sublime was a sensation of simultaneous beauty and terror created through the depiction of extreme contrasts, such as high and low vantage points, light and dark tonal values, or tumultuous and placid subject matter.

The concept of the sublime was also associated with an understanding of God and spirituality through nature. Since nature was the direct creation of God, a personal experience of nature could connect humans with the divine. This analogy was frequently suggested through imagery used by Hudson River School painters such as Thomas Cole (1801-1848) and Frederic Church (1826-1900), and similar ideas found expression in writings by American Transcendentalists like Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) and Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862).

Several paintings in your collection, including those by Asher Brown Durand (1796-1886), Johann Hermann Carmeincke (1810-1867), James Hope (1818-1892), Thomas Hill (1829-1908), and Albert Bierstadt (18301902), represent groundbreaking Hudson River School artists who began their careers in New York. To see them brought together in the intimate setting of a restored Victorian home is a remarkable experience.

PPB: In my second art history course at The University of Scranton, we learned that Thomas Cole founded the Hudson River School. Cole was born in England but lived and worked in Catskill, New York. I remember studying his painting The Oxbow (1835-1836), a view of the Connecticut River from Mount Holyoke, Massachusetts.

We also discussed Asher Brown Durand’s double portrait Kindred Spirits (1849), which depicted Cole and his friend, the American poet and editor William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878), standing on a ledge in the Kaaterskill Clove of the Catskill Mountains near the Hudson River. Commissioned as a memorial piece after Cole’s death, the painting commemorated the friendship between Cole and Bryant, as well as their shared love of nature and the connection between their disciplines of art and literature.

Asher Brown Durand (1796-1886). The Butternut Tree. Study from Nature. Lake George, New York. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

Johann Hermann Carmeincke (1810-1867). Winter in the Mountains. Oil on canvas. 1859. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

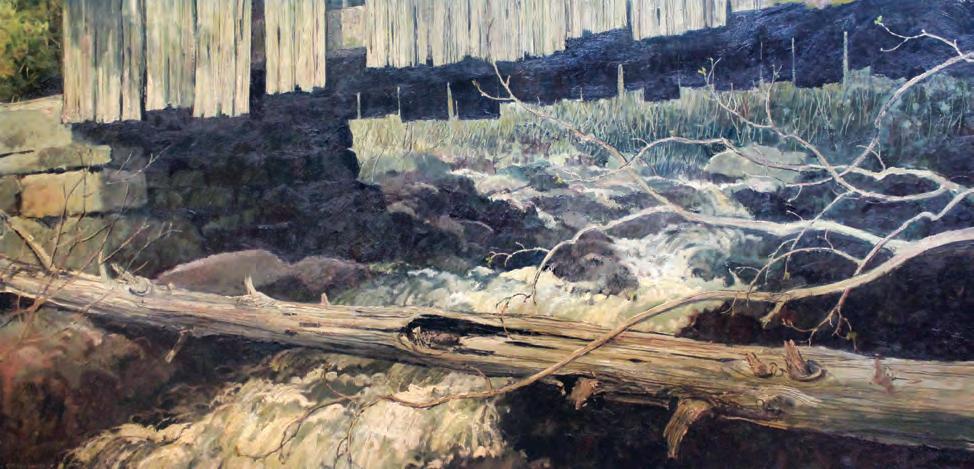

Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902). Rocky Glen (Rock and Forest Study). Oil on canvas. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

Kindred Spirits achieved some notoriety in 2005 when it was sold at auction for $35 million. The painting was owned for many decades by the New York Public Library, but was purchased by Alice Walton, whose father founded Walmart, for inclusion in the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas. I’m fortunate to own Durand’s The Butternut Tree. Study from Nature. Lake George, New York (n.d.).

DML: A key figure in nineteenth-century American art, Durand was born in Jefferson Village, New Jersey, and initially trained as an engraver. Early in his career, he engraved a print version of the federally-commissioned painting The Declaration of Independence (1818) for artist John Trumbull (1756-1843), which received critical acclaim.

Durand was a friend and admirer of Cole, who encouraged him to pursue landscape painting. After traveling briefly in Europe, the artist returned to the United States, where he kept a studio in New York City. He also traveled throughout New England, and painted landscapes representing the Catskill, Adirondack, and White Mountains. Durand wrote about art and helped to establish the National Academy of Design in New York City, one of the earliest professional associations and educational institutions for art in the United States.

The first Durand painting I ever saw was The Beeches (1845), on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The Butternut Tree is similar in many ways, as both paintings feature vertical compositions depicting tall trees in the foreground, with a road or clearing extending into the distance.

Among the painters whose works form part of your collection, Johann Hermann Carmeincke and James Hope are the two closest in age to Durand. Born in Hamburg, Germany, Carmeincke studied and worked in Denmark, Sweden, and Italy before settling in Brooklyn, New York. Similarly, James Hope was born in Drygrange, Scotland, then moved to the United States by way of Canada, living and painting over the years in Castleton, Vermont, and Watkins Glen, New York.

I enjoy the stark quality of Carmeincke’s Winter in the Mountains (1859), with its image of a bear and fallen tree, and Hope’s dramatic Rainbow Falls. Watkins Glen (1871) is reproduced as the cover image for our catalogue. Many Hudson River School paintings presented wide, panoramic views of the landscape, observed from a high vantage point using a convention known as the magisterial gaze. The works by Durand, Carmeincke, and Hope, however, revealed more intimate scenes of nature by showing interiors of deep forest glades.

While Carmeincke and Hope are well-respected artists, the painter represented in your collection whose reputation most closely matches that of Durand is Albert Bierstadt.

PPB: I really appreciate Albert Bierstadt and was fortunate to have found his Rocky Glen (n.d.) at auction. The painting was owned by Dorrance “Dodo” Hamilton, granddaughter of the founder of the Campbell’s Soup Company. The family was from Pennsylvania, and she lived off the Blue Route in the Haverford area.

One day I was in a museum in downtown Philadelphia and happened to stop by Freeman’s, which had announcements for her estate auction. One of the paintings listed was the tree and rock study by Bierstadt, which reminded me of places where I would walk in the Pocono Mountains, so I was able acquire it.

DML: Bierstadt was born in Solingen, Prussia, but immigrated with his family to New Bedford, Massachusetts, as a baby. He studied art in Düsseldorf, Germany. After returning to the United States, he worked with members of the Hudson River School and established a studio in New York City, then traveled west and painted in the Rocky Mountains and Yosemite Valley.

Thomas Hill’s career path resembled that of Bierstadt. Born in Birmingham, England, Hill relocated to Taunton, Massachusetts, in his teenage years. He studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, associated with painters of the Hudson River School, and traveled in Europe. Ultimately, he moved to San Francisco, California, and was known for paintings of the Yosemite Valley.

PPB: One personal observation regarding Thomas Hill is that I feel a close connection to his painting Fisherman in the Woods (n.d.). It is a beautiful scene of a fly fisherman casting his long line in a rambling stream.

I love to fly fish. When I was growing up, my grandfather and father were ardent fly fishermen, and we would spend copious amounts of time on the lake water at our cottage in the mountains. I take the purist approach to fishing with tied flies. These are basically replicas of insects created by wrapping string and feathers around small hooks. Making them takes great skill, and there are many traditional patterns mimicking different types of flies.

Thomas Hill (1829-1908). Fisherman in the Woods. Oil on paper laid on canvas. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902). Western Landscape. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

A true expert studies entomology to learn about the different insects, their habitats, and their life cycles. Then, when you fly fish in a particular stream, you try to choose a lure that resembles an insect currently living and breeding in the water. The fish there will be accustomed to eating that insect as part of their natural diet, so your imitation of it will attract them to your line.

The Delaware and Lehigh Rivers, and their small tributaries, are legendary locations for fly fishing, especially for trout. When I saw Hill’s painting of the fly fisherman I thought, “Well, I don’t know what it will sell for at auction, but I’ve got to have it,” so that’s how it ended up on the wall.

DML: Paintings by Hudson River School artists working in the western United States, including Bierstadt and Hill, have been interpreted in the context American Nationalism. Scenes from the East Coast have been related to concepts of the United States as a “New Eden,” in which the natural landscape was understood as a gift from God and a sign of Exceptionalism. Subsequently, images of the American West have been connected to a categorization of new territories as a “Promised Land,” and the expansionist tenets of Manifest Destiny. Do you have a sense of a national identity that might be expressed in these paintings?

PPB: What’s amazing about the Hudson River School is that it was not an institution where you would get up and go live on campus. It was a movement, and it is fascinating to see how artists were able to consolidate art styles, travel together, and develop a new portion of the country by picking up and moving out West from the Catskills in New York to paint Yellowstone and Yosemite in Wyoming and California. It’s truly phenomenal.

DML: Within your collection, Hill’s On the Delaware (n.d.) and Yosemite Valley with Falls (n.d.) are pieces that resulted from this transition. Both are panoramic landscapes done in the style of the Hudson River School, depicting expansive scenes of steep mountains and dramatic waterways in hues of rose, purple, and gold. The landscape settings had clearly changed, but Hill’s approach to representing them had not.

Hill began painting Yosemite in 1862. He was an associate of photographer Carleton Watkins (1829-1916), who produced “mammoth” images of Yosemite during the 1860s using the wet collodion process. The photographs taken by Watkins provided part of the impetus to recognize the unique landscapes they depicted as national treasures. In 1864, President Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant designating the region as a public reserve. This act was commemorated by Hill in his painting View of Yosemite Valley (1865), owned by the New York Historical Society in New York City. Roughly a hundred years later, Ansel Adams photographed similar sites at Yosemite, bringing images that embodied their environmental significance to audiences in the twentieth century.

The role of the arts in the creation of the National Parks System was critical, as artists and photographers frequently traveled west with government survey parties documenting new territories. Perhaps the best-known example is the Geological Survey of 1871, led by Dr. Ferdinand Hayden (1829-1887), which visited the Yellowstone region. Known as the Hayden Expedition, the group included photographer William Henry Jackson (1843-1942) and painter Thomas Moran (1837-1926).

Similarly, Albert Bierstadt traveled west in 1859 with Frederick Lander (1821-1862), a government surveyor. His large-scale painting The Rocky Mountains, Lander’s Peak (1863), in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, was based in part on that experience. In 1863, he traveled to Yosemite, and continued to visit western locations throughout his career. While the subject of Bierstadt’s Western Landscape (n.d.) has not been specifically identified, the tall trees, waterfalls, and sheer cliff represented in it could easily be associated with sites in the Rocky Mountains or Yosemite.

PPB: We visited Yosemite last June. It was a great connection because we did a lot of biking and walking to the waterfalls and pristine vistas. Suddenly it would just click that these locations were the same sites which Bierstadt and Hill had viewed and painted over a century ago.

William Trost Richards (1833-1905) was another artist who produced a group of Western scenes. He was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and died in Newport, Rhode Island, but like the other painters we have mentioned traveled to various locations throughout his career. I have his little watercolor painting Yellowstone Lake. Mount Sheridan in the Distance (n.d.), which is special because it is done in a delicate, unusual medium that one does not encounter very often.

Thomas Hill (1829-1908). On the Delaware. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

Thomas Hill (1829-1908). Yosemite Valley with Falls. Oil on canvas. Undated.

The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

William Trost Richards (1833-1905). Yellowstone Lake. Mount Sheridan in the Distance. Watercolor and gouache on paper. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

Thomas Worthington Whittredge (1820-1910). Castle in the Harz Mountains. Oil on paper laid on board. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

I traveled to Yellowstone Lake in Wyoming and took a photograph of that identical area. While I was there, I wondered what made Richards think, “I’ll stop here and do a watercolor.” A lot of large oil paintings were completed by artists back in their studios based on preliminary sketches, but this small watercolor was probably done on site. It’s absolutely gorgeous.

DML: Worthington Whittredge (1820-1910), who is also represented in your collection, was born in Springfield, Ohio, and spent a decade or so traveling and painting in Europe. He studied, like Bierstadt, in Düsseldorf, and his painting Castle in the Harz Mountains (n.d.) represents that international experience, which was sometimes challenging for American painters. The image shows the mysterious silhouette of a ruined German castle on a hillside beyond a river and green trees. The work is undated, so it’s interesting to wonder when and why he might have produced it.

Art history can be full of intriguing puzzles, and you may have one in the Moonlit Landscape (n.d.) attributed to Thomas Hill. The small, vertical painting features a very particular scene of a man walking down a snowy road under a glowing full moon. The moon is depicted in a warm white color and the sky is painted with a luminous blue hue. It is a striking night scene, or nocturne, and immediately impressed me when I first saw it at your house in Easton. To my great surprise, not long after I viewed it there, I encountered a large, horizontal version of the same subject at the Montclair Art Museum in New Jersey. I would never have expected to see something so similar, within a few days’ time, in my entire life.

Variously known as Winter Moonlight or Christmas Eve (1866) the piece at the Montclair Art Museum was painted by the Hudson River School artist George Inness (1825-1894). Born in Newburgh, New York, Inness often worked in the region of the Delaware Water Gap, and the museum has a large collection of his paintings. Information published by the museum explained that Winter Moonlight might have been painted to celebrate a unique celestial event that occurred during the artist’s lifetime: in a rare alignment of circumstances, a full moon reached perigee during the winter solstice of 1866.

Interestingly, Inness is famous in Scranton for his painting of The Lackawanna Valley (c. 1855). This piece, originally commissioned by the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad for promotional purposes, is now in the collection of the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. It represents a distant view of the city and mountains from the west side of the Lackawanna River. In the center of the scene, a steam locomotive is shown crossing the river on a small bridge. The image is unusual among nineteenth-century landscape paintings, however, as the foreground features a hillside covered in tree stumps, indicating that the expansion of industry has been accompanied by the destruction of nature.

After seeing Winter Moonlight, I found it odd that both Inness and Hill would paint that same scene independently, especially if it was based on such a specific incident. I contacted art historian Michael Quick, an Inness scholar, to ask if Hill and Inness ever painted together. He doubted that they did, as records indicate that Hill was likely in Europe at the time Winter Moonlight was produced. Instead, he wondered if Moonlit Landscape was possibly misattributed to Hill, as Inness was known to have reworked several of his large horizontal canvases in smaller, vertical formats later in his career.

In the years after their creation, paintings often pass through strange and wonderful circumstances. You have done a beautiful job of restoring Moonlit Landscape, which came to you showing some wear and tear from its previous adventures. It would be a very engaging project to further research its provenance and learn more about its history.

PPB: I always enjoy discovering and caring for old paintings and learning about new attributions or background information. They do often hold surprising and complex connections.

DML: Speaking of complex connections, a notable group of painters that has received a lot of critical attention lately is the Hart family. Your collection includes paintings by William Hart (1823-1894), Julie Hart Beers (1835-1913), and Mary Theresa Hart (1872-1942). Can you explain their relationships to each other?

PPB: The Harts were an artistic family in which brothers, sisters, parents, and children established interconnected careers across two generations. Born in Paisley and Kilmarnock, Scotland, brothers William Hart and James McDougal Hart (1828-1901) came to the United States with their parents when they were young. Their sister,

Attributed to Thomas Hill (1829-1908). Moonlit Landscape. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

Julie Hart Beers (1835-1913). Summer at Mossy Brook. Oil on canvas. 1878. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

Julie Hart, was born in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. The family – which was reported to have ten children overalllater moved to Albany, New York, and William, James, and Julie became painters. Their father may have been a carriage painter, and William and James both returned to Europe for a time to study art in Scotland and Germany, respectively. Julie is thought to have received most of her artistic training from James.

William was known for his portraits and landscapes, many of which featured cows. The Autumn Landscape (n.d.) in my collection is one of them. He had a successful career and worked in the Tenth Street Studio Building in New York City, where many well-known artists rented space at the time. William also served terms as president of the Brooklyn Academy of Design and American Watercolor Society.

Julie married a journalist named George Beers, and the couple had two daughters named Marion and Kathryn. Julie was widowed early on, however, and so pursued art as a way of supporting herself and her children. She conducted art classes and painting trips for young women. Her daughter, known as Marion Robertson Beers (1853-1945), became a painter as well. Julie remarried later in life, so her name is sometimes recorded as Julie Hart Beers Kempson. I was fortunate to acquire her large oil, Summer at Mossy Brook (1878), which, like paintings in my collection by Durand, Bierstadt, and Hill, shows a forest interior.

James, like his older brother, painted landscapes and cattle scenes. He exhibited regularly throughout his life and served as vice-president of the National Academy of Design. James married an artist, Mary Theresa Gorsuch Hart (d. 1921) and the couple had two daughters, Letitia Bonnet Hart (1867-1953) and Mary Theresa Hart, who both became painters. The sisters worked in their father’s studio in New York City and were known for portrait and still life paintings. Mary Theresa Hart’s Floral Still Life (1885) is a nice example.

DML: Several art historical issues can be considered in relation to the Hart family. Since the 1970s and the emergence of feminist art history, substantial research has been done on circumstances surrounding the lives and careers of American women artists. It is clear that they routinely faced challenges in balancing the demands of work and family, and rarely entered into the arts professionally unless they received training and encouragement from male relatives who were also active in the field.

Recently, Julie Hart Beers has attracted interest as one of the very few women associated with the Hudson River School, and several museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, have acquired her work in the last few years. Two recent projects in particular highlight her art and family.

The first, Hudson River Journeys: Watercolors and Drawings by William Hart and Julie Hart Beers, was an exhibition presenting pieces by this brother and sister pair, organized by the Albany Institute of History and Art in New York. The show ran through the summer of 2023.

The second, Capturing Nature Side-by-Side, a catalogue featuring the work of Julie Hart Beers and her daughter, Marion Robertson Beers Brush, was compiled by Hawthorne Fine Art in Irvington, New York. Hawthorne represents the artists’ estates and has included pieces by Beers in curated shows of nineteenth-century women landscape painters.

Also, the range of subject matter found across works by members of the Hart family is significant. Traditionally, there has been something of a hierarchy of subject matter in European art. During the Renaissance period, many churches, including St. Peter’s Cathedral in Rome, Italy, commissioned important religious paintings during the sixteenth century, while prominent nobles commissioned portraits. In the Baroque period, history painting became popular, and a strict formula for producing it, known as the Grand Manner style, was developed and taught from the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries at the Royal Academy in Paris, France.

In a break with these precedents, however, an alternate set of artistic subjects, based on landscape, still life, and genre themes, became popular in the Netherlands during the seventeenth century. There, in the midst of a booming center of international commerce, paintings were often produced for sale on the open market, and artists sought to attract buyers by presenting familiar and recognizable images related to everyday life. The comparison between that approach to art sales, and the contemporary gallery system that developed and operates in New York City today, has frequently been made. The Harts, with their range of landscape, livestock, and still life subjects, are heirs to these historical preferences. Three additional artists represented in your collection by works related to these subjects are William Louis Sonntag (1822-1900), Jervis McEntee (1828-1891), and Andrew Melrose (1836-1901).

William Hart (1823-1894). Autumn Landscape. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

Mary Theresa Hart (1872-1942). Floral Still Life. Oil on canvas. 1885. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

William Louis Sonntag (1822-1900). Adirondack Scene. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

Jervis McEntee (1828-1891). Cabin in the Woods. Oil on canvas. c. 1860. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

PPB: Sonntag’s Adirondack Scene (n.d.) and McEntee’s Cabin in the Woods (c. 1879) are both depictions of rural homes in the wilderness. The subject appealed to me because of my own experiences of living in a cabin close to nature, and the sense of calm that it brings.

DML: Art historical information related to the McEntee painting suggests that the artist enjoyed outdoor activities as well. McEntee was born in Rondout, New York, and as a young man decided to become a painter. Beginning in 1850, he studied for a short time with Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900), a well-known Hudson River School artist who had himself been a student of Thomas Cole, and the two remained friends throughout their lives. Church was famous for his blockbuster paintings of Niagara (1857), now in the Corcoran Collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., and Heart of the Andes (1859), now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, which had attracted large audiences when they were first exhibited.

Between 1867 and 1872, Church worked with Romantic architect Calvert Vaux to design and construct a Persian-inspired Victorian villa at a site along the Hudson River, called Olana. Interestingly, Vaux’s wife Mary was McEntee’s sister, so the friendship between the Church and McEntee families was extended through that association as well. Church’s house is now a museum known as the Olana Historic Site. One of the paintings in the collection there is an oil, in color, by McEntee, titled Campsite. Church’s Camp at Millinocket (1879). The image is nearly identical to your black and white painting Cabin in the Woods, as it shows three people gathered outside of a rough structure assembled from logs, shingles, and tarps.

McEntee kept journals from the 1870s to 1890s, which have been digitized as the Jervis McEntee Diaries by the Archives of American Art in Washington, D.C. and are wonderful primary sources for research. According to entries made in September and October of 1879, McEntee spent time with Church and his wife, Isabel, on a wilderness painting trip to Maine, where they camped on Millinocket Lake in the vicinity of Mount Katahdin. The group seems to have also included fellow painter and friend Sanford Robinson Gifford (1823-1880) and his wife Mary.

Notes that might relate to the Campsite painting include the comments “Laid in a sketch of the camp,” on Tuesday, September 16, 1879; “Worked on my picture of the camp until the rain drove me out,” on Wednesday, September 17, 1879; and “Painted Mary and Mrs. C. in my camp picture,” on Friday, October 3, 1879. Other activities described during the outing include hiking, canoeing, and fishing. Since your black and white image is undated, it is difficult to know if it might have been painted before or after the work in the collection at Olana. Black and white paintings, produced using a technique called en grisaille, or gray values, were sometimes used as preparatory studies to determine lights and darks in a composition.

Sonntag’s Adirondack Scene presents a more a domestic view of a woman hanging out laundry on a clothesline. Born near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Sonntag worked and studied first in Cincinnati, Ohio, and then in New York City. Like other members of the Hudson River School, he made painting excursions to scenic nearby areas, such as the Adirondack Mountains.

Melrose’s Palisades Cliff Overlooking the Hudson River (n.d.) can also be considered a genre scene, as it is an image of outdoor leisure. The artist was born in Selkirk, Scotland, but after arriving in the United States as a young man was primarily based in New Jersey. While Melrose later visited western and southern regions of the country, he produced many landscape paintings near New York. His scene of the Palisades depicts the tall cliffs along the river, where a couple is enjoying a view of sailboats on the water.

Andrew Melrose (1836-1901). Palisades Cliff Overlooking the Hudson River. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

Ralph Albert Blakelock (1847-1919). Autumn in the Catskills. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

DML: We have discussed your interest in the Hart family of painters, but that is not the only family of artists represented in your collection. You have also acquired works by Ralph Albert Blakelock (1847-1919) and his daughter Marian Blakelock (1880-1930) that demonstrate not only shifts in nineteenth-century American art styles, but also changes in personal perceptions and painting techniques.

PPB: I am very interested in the Blakelocks, as they had fascinating lives. Ralph Albert Blakelock was born in New York City, and first studied medicine. He soon turned his focus to art and became a very independent painter with a very personal style. He did not receive formal training per se as did other artists of his time but traveled in the West and developed images based on his individual experiences.

Blakelock returned to New York City where he exhibited at the National Academy of Design and rented space in the Tenth Street Studio Building, which was a famous place for artists. His work was well-received and paintings like Autumn in the Catskills (n.d.) and Landscape with Blue Sky (n.d.) were exhibited and sold, although sometimes at low prices. At the time, Blakelock was painting in the Tonalist style. This late transitional phase of the Hudson River School approach to landscape subjects emphasized a moody experience of nature represented through atmospheric effects.

Unfortunately Blakelock was not a particularly good businessman, so he often found himself in financial trouble. As a husband and father of nine children, he felt the strain of providing for his family, and began to suffer from depression. His art style shifted, and he began to use paint in a loose, heavy, impasto technique, as seen in Untitled Landscape (n.d.). He could not earn an adequate income by selling his work, and by the turn of the century was admitted to the first of several mental institutions, where he would spend the last decades of his life.

Ironically, Blakelock’s paintings became very popular just at the time when he himself encountered health difficulties. He received critical acclaim as an innovative American artist but was sometimes exploited by those around him. Controversy especially surrounded Blakelock’s relationship Beatrice Van Rensselaer Adams, who promoted his work in a major exhibition at the Reinhardt Galleries in New York City in 1916 yet separated the artist from his family. Ultimately, most profits from Blakelock’s work benefitted dealers and galleries rather than the artist himself.

Blakelock’s daughter Marian followed in her father’s footsteps and also became a painter. She too struggled with depression and spent time in a psychiatric facility. Little research has been done on her history, but there is an increasing interest in her life and career. Landscape with Trees (n.d.) is typical of her Tonalist-inspired style. Marian’s approach to painting was similar to that of her father, and the pair had a joint exhibition at Young’s Art Galleries in Chicago, Illinois, in 1916. Since Ralph Albert Blakelock’s work sold for higher prices after his illness and death, many forgeries of it were produced. There is some indication that dealers also changed the signature on paintings by Marian Blakelock to that of Ralph Albert Blakelock to take advantage of this trend.

DML: To understand the extent to which Blakelock’s work differed from that of his predecessors, it is helpful to remember and consider the evolution of art styles in the United States across the nineteenth century. In the early 1800s, members of the Hudson River School like Durand painted detailed, monumental scenes of the American landscape that conveyed an emotional sense of spirituality and nationalism through contrast and the sublime. The images they produced seemed almost larger than life and carried with them a good deal of Christian symbolism. They implied that the United States was a New Eden, where utopia, unmarred by the past troubles of Europe, was a real possibility. The Civil War, however, shattered that expectation, and artists searched for a new approach to landscape painting, grounded more in direct observation than cultural ideology.

By the 1860s, a variation on Hudson River School practice, known as Luminism, emerged. Sometimes linked to artists like Bierstadt, the new style emphasized a glowing quality of light and crystalline clarity of distance. While imagery continued to celebrate the beauties of nature, its presentation became increasingly deliberate and literal. An interest in formal principles of art displaced an affinity for romanticized interpretations of content. As demonstrated by New York City native James David Smillie (1833-1909) in his painting A Bit on the Hudson (1866), this change was gradual.

Ralph Albert Blakelock (1847-1919). Landscape with Blue Sky. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

Ralph Albert Blakelock (1847-1919). Asylum Painting. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

Marian Blakelock (1880-1930). Landscape with Trees. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

Alexander Helwig Wyant (1836-1892). A Brook in the Catskills. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

At the same time in Europe, Realism was gaining popularity as an art style. Inspired partly by photography, a process which quite directly used light to create literal images of the natural world, Realism advocated a direct relationship between observation and representation. American artists also gravitated towards Realist painting approaches, which gained prominence in the United States by the beginning of the twentieth century. This shift, however, was multifaceted.

Another mode of American landscape painting that emerged in the 1870s was Tonalism. Like Luminism, it emphasized a sense of light and atmosphere, with the distinction that the preferred conditions depicted were subtle and transient, rather than bright and revelatory. Tonalism was closely related to the painting methods used by artists of the French Barbizon School in Fontainebleau, France, who, like the artists of the Hudson River School, were inspired by nature and spent a large amount of time outdoors. The Barbizon painters were admired by the French Impressionists, who were in turn emulated by the American Impressionists, so their influence on art extended into the twentieth century. In addition to the Blakelocks, a painter represented in your collection is Alexander Helwig Wyant (1836-1892), and A Brook in the Catskills (n.d.) is a good example of the Tonalist style.

In regard to their stories of misplaced recognition and personal hardship, the Blakelocks have counterparts in nineteenth-century European artists like Dutch painter Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) and French sculptor Camille Claudel (1864-1943). Remembered as much for his erratic behavior and psychological challenges as for his innovative paintings, Van Gogh has achieved contemporary cult status as a tormented genius. Claudel, who struggled to establish an independent professional identity following her apprenticeship with Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), is similarly known today for both her expressive sculpture and her long confinement in a mental institution. While the trope of the suffering artist has captured the popular imagination for many years, it is counterproductive in that it tends to associate creative talent with individual instability. Many difficulties encountered by artists, however, might be traced in a less sensational way to external collective stressors, rather than internal personality traits.

The challenges faced by Marian Blakelock as a woman painting in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century were not unique. Many female artists, who were generally associated with male relatives in the arts, had problems with attribution of their works to fathers, brothers, husbands, and teachers. Name changes due to marriage, the notion that women could not paint as well as men, and the fact that women working as studio apprentices had their work signed by their “masters” all complicated this situation. Female painters who broke societal norms that prioritized marriage and a family over independence and a career might face severe repercussions. Many historical examples exist of headstrong women who were institutionalized possibly more on account of their unconventional lifestyle choices than serious medical issues.

Currently, Questroyal Fine Art often sells works by the Blakelocks, and has done a nice job of addressing these issues in exhibitions and publications. Ralph Albert Blakelock: The Great Mad Genius (2005) and Ralph Albert Blakelock: The Great Mad Genius Returns (2016) are two catalogues that consider the artist’s professional career and mental health. The second catalogue, in particular, sought to increase awareness about dementia, and funds raised through its distribution were donated to an Alzheimer’s service organization.

As art styles evolved in the United States during the nineteenth century, the occupation of “artist” itself became increasingly professionalized. Early American artists frequently sought training at the Royal Academy in London, England, or traveled to study classical art in Rome, as no formal art schools existed in the United States. However, this situation changed as the American Academy of the Fine Arts was established in New York City in 1802, then reorganized as the National Academy of Design in 1825, while the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art was founded in Philadelphia in 1805. Both institutions offered art instruction, exhibition opportunities, and professional recognition for practicing artists. Later, a more loosely structured alternative to these academies, the Art Students’ League, was organized in New York City in 1875.

Students in the late nineteenth century often supplemented education at these organizations with a seasonal cycle of study in France, training in the fall at the École des Beaux Arts, Académie Julian, or Académie Colarossi in Paris, and traveling in the spring throughout the countryside in Brittany and Normandy. Still, New York City had solidified its place in American art education, and many artists gravitated there.

James David Smillie (1833-1909). A Bit on the Hudson. Oil on canvas. 1866. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

Guy Carleton Wiggins (1883-1962). Old New York and New New York. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Mark Biedlingmaier Collection.

DML: Along with the Hart and Blakelock families, the Wiggins clan made a lasting contribution to American art history. Across three generations, father John Carleton Wiggins (1848-1932), son Guy Carleton Wiggins (18831962), and grandson Guy Arthur Wiggins (1920-2020), produced landscape and urban views increasingly particular to the evolving life and culture in New York City. Up to this point, Paul, we have mainly been discussing nineteenth-century paintings from your collection, but as we move on to works produced in the twentieth century, Mark, many of the pieces we consider will be from your collection.

The elder statesman of the Wiggins family, John Carleton Wiggins, sometimes known simply as Carleton Wiggins, was born in Turners, New York. Like William Hart, he painted cattle scenes; like Alexander Helwig Wyant, he employed a Tonalist technique. Mark, Landscape with Cows (n.d.) in your collection is typical of this subject matter and stylistic approach. Wiggins studied with Johann Carmeincke and George Inness, artists linked to the Hudson River School, and attended the National Academy of Design. He later traveled to Europe, where he became interested in the en plein air technique used by the French Impressionists, who in order to reproduce a sense of fleeting atmospheric qualities in their works, advocated the practice of painting directly outdoors. Back in the United States, Wiggins increasingly spent time in Old Lyme, Connecticut, and became associated with the emergence of the American Impressionist style at the Old Lyme Art Colony, which he helped to establish.

The son of John Carleton Wiggins, Guy Carleton Wiggins was born in Brooklyn, New York. Guy Carleton Wiggins was first trained by his father, and like him was educated at the National Academy of Design. He later attended the Art Students League and studied with William Merritt Chase (1849-1916) and Robert Henri (18651929), painters who were associated with American Impressionism and the Ashcan School. American Impressionist artists sought to represent contemporary scenes, often of urban life as well as landscape views, by painting on site with swift brushstrokes and complementary colors. The results were frequently high-key, sophisticated images of pleasant subject matter. Painters of the Ashcan School, while they embraced the direct quality of American Impressionism, expanded its range of subjects and colors to include dark-hued representations of controversial topics. While he painted scenes of New York City, John Carleton Wiggins was also associated with the Old Lyme Art Colony and the American Impressionist painters who congregated there.

In Paul’s collection, Wall Street (n.d.) is a beautiful urban snow scene by Guy Carleton Wiggins painted in the style of the Ashcan School. It depicts a busy yet serene city thoroughfare bustling with cars and pedestrians and includes a view of Trinity Church in the distance, which was one of his favorite subjects. Wiggins achieved a little notoriety in popular culture several years ago, as his painting Old Trinity, New York Winter (1930) was featured on the PBS television series Antiques Roadshow

Also born in Brooklyn, New York, the son of Guy Carleton Wiggins, Guy Arthur Wiggins (1920-2020), carried on the family art tradition for a third generation, documenting New York City in impressionistic images like Winter at the Metropolitan (n.d.). At the advice of his father, however, Guy Arthur Wiggins did not pursue art as his primary occupation, but instead painted professionally after retiring from a long career in the Foreign Service.

MJB: As I started reading about the Wiggins family, it was fascinating to discover the artists’ relationships to each other. I found Guy Carleton first, then backtracked to research John Carleton, and was thrilled when the opportunity arose to purchase the Guy Arthur work. They are a wonderful family of exceptional talent.

DML: Other artists, like Johann Berthelsen (1883-1972) produced images of New York City landmarks including the Brooklyn Bridge (n.d.) in Paul’s collection, and the Queensboro Bridge (n.d) in yours. Also in your collection is an Art School Scene (1915) by Oswald Jackson (1870-1916), which is emblematic of a new interest in formalized art education and urban cultural status. The image is a nice representation of the camaraderie artists enjoyed in urban art schools like the National Academy of Design in New York City, or the École des Beaux Arts in Paris. The students – all men in this particular image, although women were also sometimes accepted in art schools by the turn of the century – are dressed in suits and smocks, indicating the professional and businesslike dimension of their chosen career.

MJB: I’m glad you commented on that painting. I don’t know what possessed me to buy it, but when I saw it I had to have it. For some reason I thought it was just perfect. I have no artistic talent whatsoever, but this image of a group of young gentlemen diligently painting together is one of my favorite works.

John Carleton Wiggins (1848-1932). Landscape with Cows. Oil on canvas. The Mark Biedlingmaier Collection.

Guy Carleton Wiggins (1883-1962). New York Harbor. Oil on canvas. 1928.

The Mark Biedlingmaier Collection.

Johann Berthelsen (1883-1972). Brooklyn Bridge. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Paul Biedlingmaier Jr. Collection.

Guy Arthur Wiggins (1920-2020). Winter at the Metropolitan. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Mark Biedlingmaier Collection.

DML: At the turn of the twentieth century, for the first time in art history, New York City gained prominence as an international cultural center. Artists like Guy Carleton Wiggins understood the implications of that transition. The American Realists and Ashcan School painters saw what was happening on the Lower East Side of Manhattan and recognized that the United States had forged an international identity.

They didn’t show it artistically through the use of modernist styles developing in Europe, but rather in terms of their diverse, urban, working-class subject matter. They saw the variety of people and cultures that were appearing in New York City and were excited by its implications. This coalescence was taking place on American soil, but artists realized that it would redefine the United States in terms of domestic and international affairs.

MJB: Indeed. While it was not quite an era of American Imperialism, the twentieth century was a period that highlighted a sense of American Exceptionalism overall. The United States was initially perceived by European nations as a rogue and backwater environment. Then, as it helped turn the tide in World Wars I and II, the global focus shifted away from the great powers of Europe to this new nation, which had developed superior economic, military, and industrial strength. The twentieth century marked the emergence of the United States on the world stage as the epicenter of influence and prosperity.

What place could reveal this transition better New York City, the homing point for so many immigrants to the United States through Ellis Island? The burgeoning building environment of New York City reflected the sequential waves of workers to our shores through structures and neighborhoods, for example, St. Patrick’s Cathedral, Central Park, the underground subway, and Little Italy. Including Old New York and New New York (n.d.) by Guy Carleton Wiggins in the catalogue at this point is a perfect way to make that transition. The lowly horse cart in the foreground is a characteristic of old New York, and yet the billowing smokestack in the background is a sign of new New York! It presages the evolution of the city’s towering skyscrapers.

DML: This is probably obvious, but you are an international diplomat and Paul is a financial advisor. Both of you must have personal connections to New York City, which is a world center of politics and economics.

MJB: Paul and I have a long association with New York City. Even as children, with Easton being only an hour away, every so often Mom and Dad would get us up and say, “Oh, come on, let’s go to New York City.” We would go to church at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, have breakfast or lunch, then drive back to Easton. So we have roots in New York City as well. Since we’ve collected works by the Wiggins family, it’s actually fun to walk around the city and visit some of the sites painted by the artists.

Early in my career, I was detailed to the United Nations each year from 1981 to 1985 for three months at a time. I would meet and greet all the diplomats arriving for the annual United Nations General Assembly. It was a relatively low-ranking assignment, but it was an unforgettable experience. There I was, in the dead of night at three o’clock in the morning, at JFK Airport under high security provided by the Secret Service and NYPD, meeting Margaret Thatcher, Prime Minister of Great Britain, or Rajiv Gandhi, Prime Minister of India. As a young Department of State Attaché in my mid-twenties, I was designated as the representative of the United States Secretary of State and was the first official to formally greet foreign leaders as they landed in United States for the General Assembly. I will always cherish those memories from the early days of my career and ability to explore the city during our limited time.

DML: Another work in your collection, New York Harbor (1928) by Guy Carlton Wiggins, marks a related transitional point in American art history, as painters in the United States explored European concepts of Cubism, Futurism, Expressionism, and Surrealism. The efforts of artists like Marsden Hartley (1877-1943), Joseph Stella (18771946), and Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986), among others, resulted in a combined form categorized as American Modernism. While Wiggins experimented with Cubism, as evidenced by the simplified geometric forms and monochromatic color palette of New York Harbor, he later returned to working in his earlier American Impressionist style. For over one hundred years, American artists acknowledged the primacy of art in Europe, but by the midtwentieth century, European artists conceded the importance of art in the United States.

Oswald Jackson (1870-1916). Art School Scene. Oil on canvas. 1915. The Mark Biedlingmaier Collection.

Owen Cullen Yates (1866-1945). Interior of a Wood. Oil on canvas. Undated. The Mark Biedlingmaier Collection.

MJB: Following World War II, American artists finally broke with European traditions and developed a completely different vein of art unknown in Europe, which was Abstract Expressionism.

DML: Since conversations about the Hudson River and Delaware Valley exhibition and catalogue project first began, we have been discussing the ways in which the watersheds of the Hudson, Delaware, Lehigh, and Lackawanna Rivers of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania are geographically and culturally connected. Perhaps the artist who most embodies this intersection in terms of time as well as location is Owen Cullen Yates (1866-1945). You have several paintings by Yates in your collection, and I think they are important, as Yates was a significant figure in the development of art in eastern Pennsylvania.

Owen Cullen Yates was born in Bryan, Ohio, and demonstrated an affinity for art early on. Determining that he wanted to pursue a career in the arts, Yates initially relocated to New York City, where he studied at the National Academy of Design. He then spent summers on Long Island, New York, working with William Merritt Chase at the Shinnecock Hills Art Colony. Yates next trained at the École des Beaux Arts, Académie Julian, and Académie Colarossi in Paris, France. He spent summers there in Barbizon near the Forest of Fontainebleau, and also taught at a summer colony in Touraine, France.

After returning to the United States, he worked for a time in Cleveland, Ohio, before establishing a winter studio in New York City in the Van Dyck studio building. Over the course of several summers, he spent time at the Old Lyme Art Colony in Connecticut, and Cape Ann in Gloucester, Massachusetts, during the summer. Throughout the course of these adventures, he taught students, exhibited work, and became identified with the American Impressionists.

In the first years of the twentieth century, Yates periodically visited relatives in Saylorsburg, Pennsylvania, near the Delaware Water Gap. He soon began spending summers in the area and made the acquaintance of Charles Worthington, an industrialist who operated a hotel in Shawnee-on-the Delaware. Worthington was in the process of building a larger resort, called the Buckwood Inn. He admired Yates and invited him to become an artist-inresidence there, trading a plot of land and small cottage for one of the painter’s large landscapes showing the nearby valley. Since its opening in 1910, the Buckwood Inn has changed ownership several times, and is now known as the Shawnee Inn. A large painting by Yates depicting the building, however, believed to be the one exchanged for the artist’s residence nearby, is still displayed there.

At about the same time that Yates acquired property in Shawnee-on-the-Delaware, he also visited an artists’ colony on the coast of the Atlantic Ocean in Ogunquit, Maine. There he met his future wife, who had family in the region. Over the next decade, the artist spent winters in New York City and divided the rest of the year between Maine and Pennsylvania. Anne Weikart, a grandniece of the artist who had visited him at Shawnee-on-the-Delaware as a child, authored the exhibition catalogue Cullen Yates: American Impressionist (1983), for the Washington County Museum of Fine Arts in Hagerstown, Maryland. In it, she noted, Yates told friends that he preferred to work at Ogunquit in the summer, and at Shawnee-on-the-Delaware in the spring and fall, when the mountain foliage was varied in color. During the summer, he maintained, trees in the Pocono Mountains were “too green.”