The Middle Ages in Modern Games

Conference Proceedings

Vol. 4, 2023

Edited by Blair ApgarFunding was graciously provided by

Cover image courtesy of Stray Fawn Studio (The Wandering Village, 2022).

The Public Medievalist

Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Research, University of Winchester, 2023

@MidAgesModGames| #MAMG23

Copyright is retained by contributors.

Middle Ages in Modern Games

Blair Apgar, Elon University | @BlairApgar

James Baillie, Universität Wien | @JubalBarca

Robert Houghton, University of Winchester | @robehoughton

Lysiane Lasausse, Universitetet i Sørøst-Norge | @nordllys

Mariana Lopez, University of York | @Mariana_J_Lopez

Vinicius Marino Carvalho, Universidade Estadual de Campinas | @carvalho_marino

Markus Mindrebø, Universitetet i Stavanger| @markusmindrebo

Juan Manuel Rubio Arevalo, Central European University | @jmrubio120

Tess Watterson, University of Adelaide | @tesswatty

The Middle Ages in Modern Games, 2023 Conference Proceedings Vol. 4 6

Figures

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

1

Chapter 7

an der Pest [St. Roch falls ill with the plague], 1480-1520, painting on wood, 67x50 cm. Regensburg, Museum der

Chapter 8

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 14

The Middle Ages in Modern Games, 2023 Conference

Introduction

The Middle Ages in Modern Games virtual conference is an international event which brings together scholars and industry professionals to shape and reflect our understanding of the imagined, quasi-medieval worlds which populate nearly all formats of games and gaming. This year’s theme, Apocalypse and Fantasy, was two-pronged, grappling with the collision of ‘real’ and ‘unreal’ and the looming spectre of ‘what if’. As Tess Watterson noted in their opening address to the 2023 Middle Ages in Modern Games conference, fantasy and apocalypse are deeply intertwined. These concepts are, she aptly observes, at the generative core for nearly all medievalist media.1 The medieval, fantastical, and apocalyptic are deeply enmeshed in our popular consciousness, cropping up in both expected and unexpected ways. A common thread of imaginative exploration runs through both genres, offering alternative realities that diverge from the norm.

Fantasy and apocalypse interlock in the tapestry of medievalist storytelling, each weaving a distinct yet interconnected narrative. In the realms of fantasy, we traverse enchanted lands teeming with magic, mythical beings, and extraordinary quests. Conversely, apocalyptica plunges us into worlds on the brink of collapse, those which are actively failing, and those in the resulting wasteland. Often in medievalist games, these notional aesthetics share significant overlap and bleed into one another. Most recently, I have noted this in Baldur’s Gate III, where the crenelations of Moonrise Tower jut into the apocalyptic shadow-cursed lands, ruinated by the magic which emanates from the very same medieval(ish) tower.2 The‘apocalypse’occupies an interesting conceptually liminal space: it is the time between the end of something and the beginning of something else. This feeling of the inevitable ‘something else’ is precisely the point of contention for most globally minded medievalists: it is a period so vast and porous, spatially and temporally, we cannot (and should not) define it simply as a period of loss of what was (Rome) and a lack of what is yet to be (Renaissance). Apocalyptica exists under the same circumstances: it depicts the remains of a civilization of yore and the glimmer of hope of what will come.

These alternate realities can be used to explore new scenarios, marrying modern sensibilities to medieval aesthetics: as Ylva Grufstedt observes in her keynote remarks, though a player might be equipped with the medieval tools and techniques, the otherwise lack of guidance allows the player to venture beyond the traditional bounds of history, exploring near innumerable what if scenarios.3 As players navigate between the ‘historically derived’ and the ‘imagined’, they altogether diverge from conventional perceptions of the Middle Ages, altogether creating something new. The struggle between the ‘real’ and ‘unreal’, she notes, has resulted in a staggeringly natural transfusion of deliberately medieval

1 Tess Watterson, “Middle Ages in Modern Games: Introductory Remarks,” Twitter, 6 June 2023, https://twitter.com/tesswatty/status/1665992487612329984.

2 Larian Studios, Baldur’s Gate 3, Larian Studios, (PC Windows, macOS, PlayStation 5, Xbox One) 2023.

3 Ylva Grufsted “Beyond Epistemological Troubles: Perspectives on Historicial Speculation in Medieval Games,” 6 June 2023, https://twitter.com/ylva_grufstedt/status/1666037379537174529

elements into games which otherwise make no claim to that particular historic past.4

Inversely, medievalist games often draw on the same conditions of apocalyptic ones: the breakdown of social norms and hegemonies, and as Kienna Shaw remarked in their keynote thread, the use of “dark material” (slavery, sexual violence, homo/transphobia, sexism etc.) as shorthand that this fictive world is worse than our own.5 While fantasy often exempts itself from the confines of historical reality, this year’s speakers have made it clear that the biases and irrationalities (the “dark materials”) of the Middle Ages (and our notions of it) can and will persist in the medievalist media. It is, as Shaw muses, how developers deploy such materials that matter, rather than their presence at all: “If the Medieval era, current day, and our potential post-apocalyptic future isn't necessarily delineated by the presence or lack of violence and bigotry, then how we evoke a Medieval or post-apocalypse setting shouldn't be focused on showcasing violence and bigotry.”

To that end, the speculative/fantastical nature of medievalist games means we can and should expect the ability to move beyond the strictly historic. To move beyond, we must implement critical approaches that allow for plausible exploration and discovery. This is where epistemes – in this case the “real” and the “imagined” – collide. Rather than continue to otherize through the unquestioning acceptance of dominant historical trends, these games should highlight and explore marginalized identities. Though this may necessitate some creative in-filling, this generative process is, on the whole, enrichening to the development of medievalist ludonarratives. As Watterson so aptly notes “Creativity is a part of doing historical research as much as it is a part of making and playing historical games.” 6 The historian must engage in creative speculation as much as their counterparts in game development, and thus must be able to negotiate a path forward. Grufstedt asks “What might studying speculation and creativity among developers tell us about the way history in games is made and conveyed?”

This is, in part, the pursuit of the MAMG conference: to unite developers and historians in order to find a path forward. Our sessions involved speakers participating in diverse discussions, encompassing a broad range of subjects, including individuals from both academic and non-academic backgrounds. The overwhelming takeaway was that worldbuilders must venture beyond the historical narrative already at the whim of interpretative trends to draw out the stories of marginalized groups which may complicate, disrupt, or outright challenge existing accounts.

The organisation of this event was spearheaded by a group of scholars from a variety of specialties and backgrounds. The event was graciously sponsored by Slitherine Games and Intellect Books and supported by the Centre for Medieval

4 Ylva Grufsted “Beyond Epistemological Troubles: Perspectives on Historical Speculation in Medieval Games,” 6 June 2023, https://twitter.com/ylva_grufstedt/status/1666037379537174529

5 Kienna Shaw, “Challenging the ‘Dark’ of ‘Dark Ages’ Games,” Twitter, 8 June 2023, https://twitter.com/KiennaS/status/1666906814393245710.

6 Tess Watterson, “Middle Ages in Modern Games: Introductory Remarks,” Twitter, 6 June 2023, https://twitter.com/tesswatty/status/1665992487612329984

The Middle Ages in Modern Games, 2023 Conference Proceedings Vol. 4 9

and Renaissance Research at the University of Winchester and The Public Medievalist. Images for the conference’s promotional material was graciously provided Stray Fawn Studio’s from their 2022 title The Wandering Village 7 We hope to see a lot of new and fascinating developments at the fifth Middle Ages in Modern Games virtual conference next year which will take place June 4-7. The conference will be moving away from Twitter/X into a more permanent format which will allow the conference greater flexibility and staying power. This transition will better mirror the moral and ethical standards of MAMG, and will better foster a space conducive to meaningful, enduring discussions while respecting these values. The call for papers will be released in early 2024 across all media platforms.

Bibliography

1 Grufsted, Ylva. “Beyond Epistemological Troubles: Perspectives on Historical Speculation in Medieval Games,” 6 June 2023,

https://twitter.com/ylva_grufstedt/status/1666037379537174529

2 Larian Studios, Baldur’s Gate 3, Larian Studios, (PC Windows, macOS, PlayStation 5, Xbox One) 2023.

3 Shaw, Kienna. “Challenging the ‘Dark’ of ‘Dark Ages’ Games,” Twitter, 8 June 2023, https://twitter.com/KiennaS/status/1666906814393245710

4 Stray Fawn Studio, The Wandering Village, Stray Fawn Publishing, WhisperGames, (PC Windows, macOS, Xbox One) 2022. https://strayfawnstudio.com

5 Watterson Tess. “Middle Ages in Modern Games: Introductory Remarks,” Twitter, 6 June 2023,

https://twitter.com/tesswatty/status/1665992487612329984

7 Stray Fawn Studio, The Wandering Village, Stray Fawn Publishing, WhisperGames, (PC Windows, macOS, Xbox One) 2022. https://strayfawnstudio.com

Gender and Race

“Are We the Baddies?”: Presentation of the ‘Other’ as Apocalyptic1

QUINN BOUABSA-MARRIOTT, UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS | @QUINN5566In fiction, there has been a long-term insistence on the need for antagonists to be clearly demarcated as ‘bad’ or ‘evil’. As argued by Robert Tally Jr, it offers the straightforward identity of an ‘enemy’ as a shortcut for overcoming the confusion and complexity of a world’s conflict, which also acts as a justification for the actions taken by the protagonist(s).2 Labelled as the trope of‘evil races’, it appears prevalently in the fantasy genre, particularly in the works of J.R.R Tolkien with his use of Orcs. His use of this trope contributed greatly to the genre and its use in gaming is clear across many titles.

Among these is the 2009 game, Dragon Age: Origins. Set in the world of Ferelden, the player is recruited as one of the ‘Grey Wardens’ whose goal it is to defend the world from creatures collectively known as the ‘Darkspawn’. With no free will of their own, the Darkspawn are led by an ‘Archdemon’, whose awakening marks the start of these conquests. Beyond their aimless urges to spread bloodshed and destruction across the world, the Darkspawn are not presented with any clear or complex motivations. They exist in the game, therefore, simply to be killed. This not only deprives them of any agency as a group, but it also severely limits user choice, inevitably leading players down the path of a binary opposition.

Beyond the convenience such simplistic narratives provide, a contributing factor to this continued trend can be connected to a perceived historical basis. In the world of Dragon Age, much of the mystery surrounding the Darkspawn leads many of the non-playable characters (NPC) throughout the game to interpret their attacks as a sign of divine punishment, a phenomenon that is historically attested in contextualising the ‘other’. A fitting historical comparison that we can look to are the Mongol conquests of the thirteenth century.

As with the Darkspawn in Ferelden, the Mongols spontaneously appeared in the Christian world with very little known about them. Necessitated by a need to categorize them within an existing framework, Suzanne Lewis explains that the Mongol slaughter of both Christians and Muslims led many Westerners to believe that they were set upon the world as an apocalyptic punishment for the sins of mankind.3 This process of demonizing‘others’, therefore, is not completely rooted in a desire for simplified stories, but also represents a historical trend of how outsiders were framed and understood.

The problem with this form of antagonism, however, is that it was not monolithic. As Felicitas Schmieder points out, many Christians who had encountered the Mongols in the Near East had already managed to co-operate with them, using

1 This paper can be viewed in its original format here: https://twitter.com/Quinn5566/status/1666135373876015127

2 Robert T. Tally Jr. ‘Demonizing the Enemy, Literally: Tolkien, Orcs, and the Sense of the World Wars’, Humanities, 8 (2019), 3.

3 Suzanne Lewis, The Art of Matthew Paris in the Chronica Majora (London: University of California Press, 1987), 283.

their relationship to promote their own faith and ways of life.4 The same was true among Europeans, who had received several embassies with reports on the possibility of Mongol conversion to Christianity as well as a military alliance against the Mamluks of Egypt.5

The idea of ‘evil races’, therefore, should not be thought of as the default. Rather, it is an intentional design choice in how ‘others’ can be depicted. It is not a requirement. There are many examples of games that have, instead, chosen to take on a much more nuanced approach. The Fallout series is well-known for this with its use of Super Mutants. In the original Fallout, while the overarching narrative frames the mutants as antagonists who seek to turn every human into a super mutant, including the residents of the player’s vault, they are not mindlessly evil.6 There are individual mutants with personalities and clear motivations. You can even end up agreeing with their goals and choose a ‘Mutant Ending’.

We also find this complexity in Tyranny but in this case the player is the villain, working to conquer the region of ‘Tiers’ for the ‘Overlord’.7 As the ‘Fatebinder’, however, your mission also involves mediating disputes among the Overlord’s armies as well as between them and local communities. Those interactions can either be oppressive or co-operative depending on the player’s approach. The freedom of dialogue choice between the player, the Overlord’s armies, and the inhabitants of Tiers, allows for a wide-ranging variety of options.

In these examples, both within and outside of the fantasy genre, it is clear that there is no single perspective of the‘other’. While villains can certainly be seen as world-ending, they can also just be seen as people, who express their own agency as individuals with different thoughts, beliefs, and goals. This leads us to the conclusion that tropes like ‘evil-races’, inspired from popular conceptions of history, largely constrain these narratives. Developers who have gone beyond this norm have proven that there is plenty of room for depicting ‘others’, even as antagonists, in new and meaningful ways.

Bibliography

1 Interplay Productions. Fallout. Interplay Productions (PC Windows), 1997.

2 Jackson, Peter. The Mongols and the West: 1221-1410. London, England: Longman, 2005.

3 Lewis, Suzanne. The Art of Matthew Paris in the Chronica Majora. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1992.

4 Obsidian Entertainment. Tyranny. Paradox Interactive (PC Windows, Mac), 2016.

4 Felicitas Schmieder, ‘Christians, Jews, Muslims and Mongols: Fitting a Foreign People into the Western Apocalyptic Scenario’, Medieval Encounters: Jewish, Christian and Muslim Culture in Conference and Dialogue, 12 (2006), 283.

5 Peter Jackson, The Mongols and the West, 1221-1410 (London: Pearson Longman, 2005), 166.

6 Interplay Productions, Fallout, Interplay Productions (PC Windows), 1997.

7 Obsidian Entertainment, Tyranny, Paradox Interactive (PC Windows, Mac), 2016.

Middle Ages in Modern Games, 2023 Conference Proceedings Vol. 4 13

5 Schmieder, Felicitas. “Christians, Jews, Muslims and Mongols: Fitting a Foreign People into the Western Christian Apocalyptic Scenario.” Medieval Encounters 12, no. 2 (2006): 274–95.

https://doi.org/10.1163/157006706778884880.

6 Tally, Robert, Jr. “Demonizing the Enemy, Literally: Tolkien, ORCs, and the Sense of the World Wars.” Humanities 8, no. 1 (2019): 54.

https://doi.org/10.3390/h8010054.

The Dragon Age Series and the Alternate Reality of a Matriarchal

Church

1

ANDREAS NUGROHO SIHANANTO, DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATICS, UNIVERSITAS

PEMBANGUNAN NASIONAL VETERAN JAWA TIMUR

PRATAMA WIRYA ATMAJA, DEPARTMENT OF DIGITAL BUSINESS, UNIVERSITAS PEMBANGUNAN

NASIONAL VETERAN JAWA TIMUR

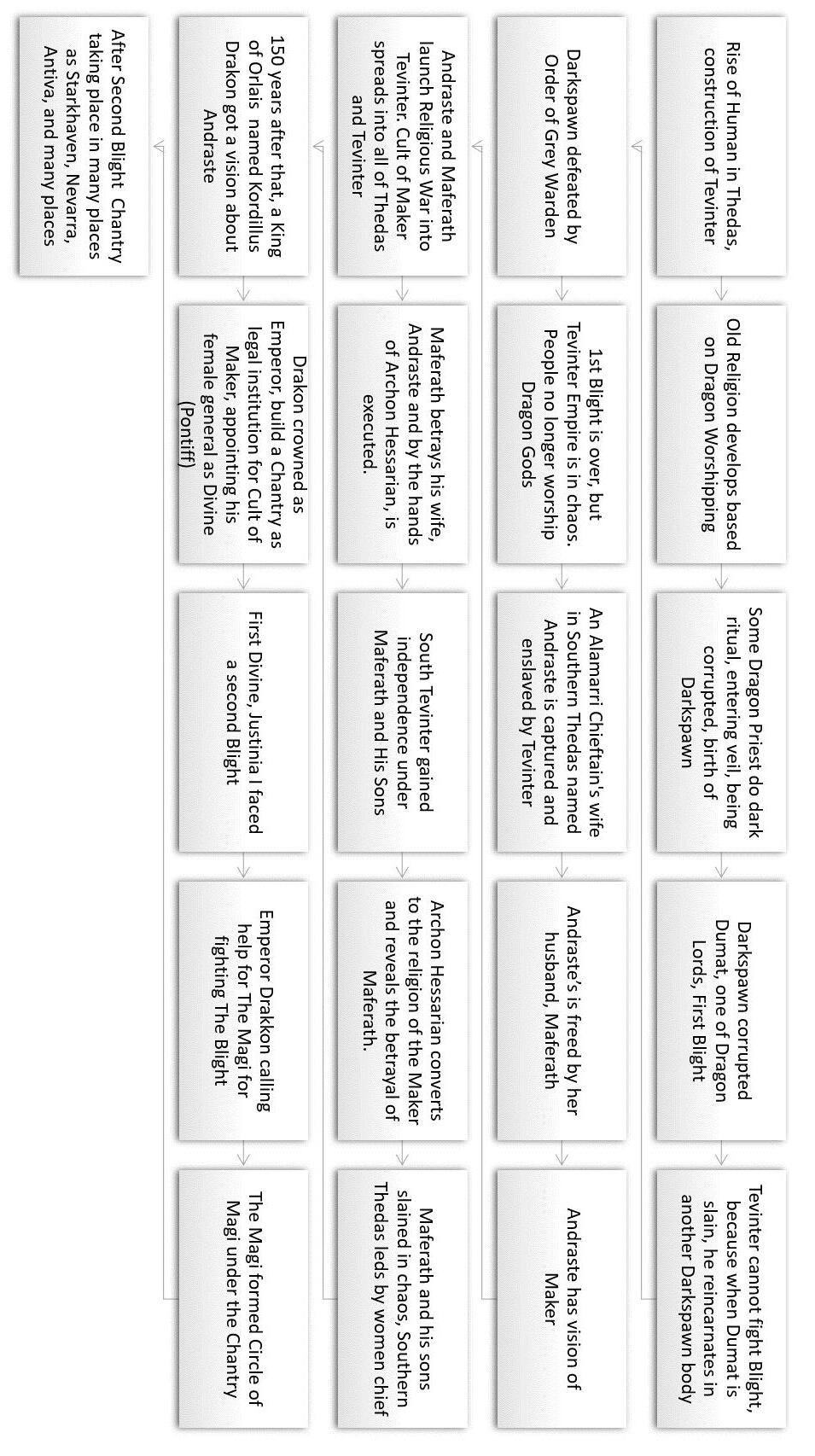

Dragon Age Series (DAS) is an RPG game franchise consisting of 3 main instalments spawned from 2009-2014. Set on a world named ‘Thedas', the game is predominantly populated mostly by human race, most of whom follow a single religion named (Orlesian) Chantry 2 The Chantry has a similar construction to the Catholic Church but rather than male clerics, The Chantry’s clerics are mostly women. This interesting concept made us compose two research questions:

1. What factors lead to Matriarchal Church?

2. Does Dragon Age properly portray the factors?

To answer those two research questions, we must delve into the lore of DAS. In the lore of DAS, there are some factors which lead to the Creation of a Matriarchal Church such as:

1. Abuse of (mostly male) mage leaders of Tevinter empire to non-mage human and non-human

2. The betrayal of Tevinter Priests (all males) and their gods. Through worshipping dragons, who were seen as false deities, the Tevinter Priests sought entry into the forbidden Golden City, believed to be the dwelling of the one true god, The Maker. However, this forbidden endeavor resulted in The Maker withdrawing, and as a consequence, the priests inadvertently gave rise to a new corrupted race known as the Darkspawn.

3. Chantry’s central figure, their prophet, Andraste, is a woman.

4. The death of Andraste was caused by her own husband's (Maferath) betrayal. Her death caused the Cult of Andraste to spread around Thedas but with different interpretations.

5. 150 years after Andraste’s death, a nobleman named Drakkon builds a new Orlesian Empire and formed Chantry as its formal state religion. Chantry is headed by a female priest named the Divine.

There are two arguments of choosing woman as the Divine. First, the position is meant to represent Andraste’s successor as a warrior-maiden who saves the world. Secondly, male clerics are thought to be easily corrupted such as Tevinter’s priest who became Darkspawn, and Maferath, the mortal husband and eventual betrayer of the prophet Andraste. Because The Chantry teaches that all men share in the same sin as Maferath, men cannot advance beyond the rank of ‘brother’ in the Chantry.

1 This paper can be viewed in its original format here: https://twitter.com/ANSihananto/status/1667079775662522368.

2 Silvia Pettini, “You’re Still the [{M}hero][{F}heroine] of the Dragon Age: Translating Gender in Fantasy Role-Playing Games,” mediAzioni 30, no. July (2021): 70–96.

We might also look to the origins of the Chantry. It was during the reign of Emperor of Orlais, Kordillus Drakon I, that saw the codification of laws and the spread of the Chant of Light, which laid the foundation for the Chantry. Drakon himself was a major proponent of Andraste and worked to spread her teachings. Perhaps as the central figure of the faith, Andraste's gender and her deeds as a powerful woman have influenced the perception of the Divine being a woman, seen as a symbolic connection to Andraste herself. The unification of the Chant of Light also helped create a powerful base of support for the emperor and gave credence to his claim on the throne. This also happened in real world in Middle Ages when kings and emperors need Church blessings to support their claim on throne as described by Eichbauer.3

By forming the Chantry and appointing his own female general as Divine, Drakon consolidated his power. This consolidation also led to collapsible power structures which could be eliminated if threatened by rebellion, such as the Circle of Mages, an institution designed to train and regulate mages. The Circle of Magi became an essential part of the governance of magic within the Dragon Age world. Mages within the Circle were expected to adhere to strict regulations, which included living within theCircle Towers and being monitored by the Templar Order, an organization sanctioned by the Chantry to oversee and control mages. As such the relationship between the Chantry and mages is complex and often contentious, and one marked by periodic rebellion. This control of magic, however, became core to the ways in which the Chantry sought to manage magic, leading to a female-centric control of magic in Thedas.

If we examine the characteristics of female leadership compiled by Zenger & Folkman,4 some characteristics of women’s leaders are:

• Takes initiative

• Resilience

• Practices self-development

• Drives for results

• Displays high integrity and honesty

• Develops others

• Inspires and motivates others

• Bold leadership

• Builds relationships

• Champions change

• Establishes stretch goals

• Collaboration and teamwork

• Connects to the outside world

• Communicates powerfully and prolifically

• Solves problems and analyses issues

3 Melodie H Eichbauer, “The Shaping and Reshaping of the Relationship between Church and State from Late Antiquity to the Present: A Historical Perspective through the Lens of Canon Law,” Religions 13, no. 5 (2022), https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13050378.

4 Jack Zenger and Joseph Folkman, “Research: Women Score Higher Than Men in Most Leadership Skills,” Harvard Business Review, June 25, 2019, https://hbr.org/2019/06/research-women-score-higher-than-men-in-most-leadershipskills

The characteristics described above mostly manifested in three characters: Grand Cleric Elthina,5 Mother Giselle and Divine Justinia V 6 Elthina likes to inspire the just and compassionate, even those of another faith, but failed to see that her Templars enacted abuse on the mages. Her inability to recognize and stamp out the maltreatment resulted in her death, the rebellion of the Circle of Magi rebelled and threw all of Thedas into chaos. This character has similar attributes with St. Hildegard of Bingen, a German Benedictine abbess lived on 12th century. Hildegard was smart and capable both in religious and scientific subject but could not fight the authority when she refused to exhume the body of an excommunicated man who had been buried in consecrated ground. The Church ruled that she is not allowed to take the Eucharist, a ruling which was only reversed four months prior to her death.7

Giselle is mother who always cared for the poor, loyal to Chantry teaching and never stay silent for every injustice done. Her presence in Dragon Age: Inquisition is mainly as moral support but without her, the protagonist’s organization rapidly declines. Her character is similar with Mother Teresa of Calcutta, who was known as 20th century's greatest humanitarians,8 except with her tendency to speak up for every injustice while stay loyal to Chantry.

Divine Justinia V is portrayed as a compassionate Divine, supporting Giselle even other clerics dislike her, but one who is capable enough to play in espionage and politics. Divine Justinia called a summit, intending to negotiate a truce between the mage rebellion and the templars splintered from the Chantry, but was killed before any such agreement could be reached. Her death subsequently threw the office of the Divine into anarchy Divine Justinia shares characteristics with Saint Olga from Kievan Rus, who revered as both fierce, cunning, and capable queen that avenge her husband death but also a saint who introduced her religion to her domain.9

Based on the explanation above, we can conclude that:

1. The lore of DAS made the factors to build Matriarchal Church (Chantry) very reasonable. It was being proved by culture of Thedas who view women’s status as same as men, then the events that happened in DAS have similarity with events in our world in Middle Ages.

2. The portrayal of Chantry’s leaders also fulfils the condition in real world’s female leadership style as described above.

5 Bioware. Dragon Age II. Electronic Arts (PC Windows, Mac, PlayStation, Xbox), 2011.

6 Bioware. Dragon Age Inquisition. Electronic Arts (PC Windows, Mac, PlayStation, Xbox), 2014.

7 Medievalists.net, “Hildegard von Bingen: A Timeline,” Medievalists.net, 2010, https://www.medievalists.net/2010/10/hildegard-von-bingen-a-timeline/.

8 Biography.com, “Mother Tresa,” Biography.com, 2020, https://www.biography.com/religious-figures/mother-teresa

9 Medievalists.net, “Grand Princess Olga: Pagan Vengeance and Sainthood in Kievan Rus,” Medievalists.net, 2010, https://www.medievalists.net/2010/02/grand-princessolga-pagan-vengeance-and-sainthood-in-kievan-rus/

Bibliography

1 Biography.com. “Mother Teresa.” Biography.com, 2020.

https://www.biography.com/religious-figures/mother-teresa.

2 Bioware. Dragon Age II. Electronic Arts (PC Windows, Mac, PlayStation, Xbox), 2011.

3 Bioware. Dragon Age Inquisition. Electronic Arts (PC Windows, Mac, PlayStation, Xbox), 2014.

4 Eichbauer, Melodie H. “The Shaping and Reshaping of the Relationship between Church and State from Late Antiquity to the Present: A Historical Perspective through the Lens of Canon Law.” Religions 13, no. 5 (2022).

https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13050378.

5 Medievalists.net. “Grand Princess Olga: Pagan Vengeance and Sainthood in Kievan Rus.” Medievalists.net, 2010.

https://www.medievalists.net/2010/02/grand-princess-olga-paganvengeance-and-sainthood-in-kievan-rus/.

6 . “Hildegard von Bingen: A Timeline.” Medievalists.net, 2010.

https://www.medievalists.net/2010/10/hildegard-von-bingen-a-timeline/.

7 Pettini, Silvia. “You’re Still the [{M}hero][{F}heroine] of the Dragon Age: Translating Gender in Fantasy Role-Playing Games.” mediAzioni 30, no. July (2021): 70–96.

8 Zenger, Jack, and Joseph Folkman. “Research: Women Score Higher Than Men in Most Leadership Skills.” Harvard Business Review, June 25, 2019.

https://hbr.org/2019/06/research-women-score-higher-than-men-in-mostleadership-skills.

Flower of Chivalry: Tropes of Knighthood and Gender in The Knight & the Maiden1

ANDREAS KJELDSEN, STARK RAVING SANE GAMES | @VERYSRSGAMESThe Knight & the Maiden: A Modern Medieval Folk-Tale is a forthcoming comedic narrative adventure game with visual novel elements set in a secondary world inspired by our own world around the year 1500.

The game's story follows the main character Charlotte who disguises herself as a Mystery Knight in order to win a tourney and use the winner’s boon to free her unjustly imprisoned father, while also pursuing her growing romance with the fair Princess Iris. Through seven chapters, Charlotte must defeat seven knightly opponents, each one based on a common cultural or literary trope related to chivalry and knighthood, such as Sir Emmett the Courtly Lover, Sir Gareth the Questing Knight, and Count Leogrance the Power-hungry Noble.

Rather than being "traditional" exemplars of honourable knights, these opponents are all deeply flawed individuals, with character flaws ranging from the merely misguided to in the later parts of the story outright murders and high-stakes political intrigues. These character flaws feed into a core part of the gameplay Charlotte is not a trained jouster, so instead she must use subversion to expose or exploit each opponent's flaw in order to shake their self-confidence enough to be able to defeat them in the joust.

To look at one of these characters in more detail, the opponent from Chapter 3, Sir Bertrand, the so-called “Hero of Lethelsberg”, owes his reputation as a great war hero to a misunderstanding during a battle fifteen years before the events of the game. Sir Bertrand has prospered greatly from his undeserved reputation, but he is also keenly aware that his life is built on a lie a sense of guilt that will give

1 This paper can be viewed in its original format here: https://twitter.com/VerySRSGames/status/1667086788656078850

Charlotte the opening she needs, if only she can uncover the truth of what really happened at the battle.

Since the story progresses through indirect/subversive, rather than direct/violent means, and also because Charlotte/the Mystery Knight inhabits a position of gender fluidity, the narrative is able to play with themes of gender, power structures and social standing. In particular, the story examines the concept of knighthood itself: While the opponents enjoy the formal status of knighthood, all of them fail each in their own way to live up to the moral ideals and standards of behaviour traditionally expected from knights. At the same time, Charlotte who is excluded from knighthood by her patriarchal society is arguably the story's only "true knight", as she acts to defend the defenceless (her imprisoned father), to seek justice, and to win the favour of her love, Princess Iris.

More broadly, the story is also inspired by the changing perception of knighthood in the Late Middle Ages, as new technologies made the traditional military role of the armoured knight an anachronism and tournaments became elaborate spectacles rather than wargames.

Works like Le Morte d’Arthur presented a nostalgic and idealised vision of knighthood at odds with an often-brutal reality (much like the seven opponents fail to live up to their ideals), a failure that fundamentally brings into question the legitimacy of their elevated status and of the patriarchal society they inhabit.

Magic, Medievalism and Modernity

Magic, Modernity and Humoresque. Visuality of a Pseudomedieval Village in The Sims: Makin' Magic Expansion Pack1

EMILIJA VUKOVIC, UNIVERSITY OF BELGRADE | @EMILIJA26753849"The Sims" is a life simulation computer game developed by Maxis.2 The game focuses on creating a virtual existence for digital characters known as Sims, which involves tasks like buying or constructing houses, fulfilling their desires, and managing their emotions. The final and impressive expansion pack for "The Sims" is titled "Makin' Magic." This expansion pack introduces magical elements, allowing Sims to use spells and magic based on mystical ingredients. It also introduces a new sub-neighbourhood called Magic Town, where Sims can explore magical activities.3

The visual presentation of this enchanting village, where magic is reminiscent of medieval traditions, serves as the primary focus of research. Notable features

1 This paper can be viewed in its original format here: https://twitter.com/Emilija26753849/status/1666422498072702979

2 Maxis. The Sims: Makin’ Magic. Dragon Age Inquisition. Electronic Arts & Aspyr Media (PC Windows, Mac), 2003

3 For general works, consult: Michael Ruckenstein, “Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture,” in Leisure and Ethics: Reflections on the Philosophy of Leisure, ed. Gerald S. Fain (Oxon Hill, MD: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 1991), 237–44; Martha W. Driver and Sidney F. Ray, eds., The Medieval Hero on Screen: Representations from Beowulf to Buffy (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2004); Simon Egenfeldt-Nielsen, Jonas Heide Smith, and Susana Pajares Tosca, Understanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction, 4th ed. (London, England: Routledge, 2019).

include dragon keeping and Bonehilda, a skeletal maid symbolizing medieval associations, particularly Brunhilda.

To access the village, players can either jump into a ground hole or travel by balloon. Upon arrival, whimsical music sets the tone, accompanied by the sounds of a French accordion. The surreal narrative that unfolds, involving holes, balloons, carnival lots, and the visual portrayal of pseudo-medieval elements, evokes a sense of absurdity reminiscent of supernatural genres, such as the renowned novel "The Master and Margarita." This sensation arises from the juxtaposition of contrasting themes, such as Sims gaining lycanthropy through the "Beauty and the Beast" spell, which takes on a medieval context within the framework of "Sims Makin' Magic."4

Upon arrival in Magic Town, visitors can choose between exploring the grand gypsy carnival or the residential area known as Creepy Hollow. Certain carnival lots feature designs reminiscent of pseudo-gothic medieval architecture, including "Spooktacular Spot" with its medieval-style building, an old graveyard, and a phone booth for acquiring balloons. Other carnival-themed lots include pseudo-medieval roller coasters and stages for magical performances.

During these visits, players may encounter the local apothecary, Tod, dressed in a plaid waistcoat and bow tie. He offers items like beeswax and toadstools, reminiscent of popular components from the Middle Ages. This amusing fusion of conflicting visual and musical elements contributes to an overall sense of whimsy and absurdity. The term "humoresque" aptly captures the essence of the entire narrative.

4 Melissa Bianchi, “Claws and Controllers: Werewolves and Lycanthropy in Digital Games,” Revenant: Critical and Creative Studies of the Supernatural 2 (2016): 127–45, https://nsuworks.nova.edu/hcas_dcma_facarticles/16.

In conclusion, the town's visual identity merges medieval magical traditions, carnival aesthetics, and modern gadgets. However, the presentation might seem somewhat overwhelming to absorb visually. Given that researchers have utilized "The Sims" game to enhance cognitive capacities, it's worth contemplating the potential effects of the specially released "Makin' Magic" expansion pack. Could it hold additional beneficial properties?5 This question remains unanswered.

Bibliography

1 Bianchi, Melissa. “Claws and Controllers: Werewolves and Lycanthropy in Digital Games.” Revenant: Critical and Creative Studies of the Supernatural 2 (2016): 127-145. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/hcas_dcma_facarticles/16.

2 Driver, Martha W., and Sidney F. Ray, eds. The Medieval Hero on Screen: Representations from Beowulf to Buffy. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2004.

3 Egenfeldt-Nielsen, Simon, Jonas Heide Smith, and Susana Pajares Tosca. Understanding Video Games: The Essential Introduction. 4th ed. London, England: Routledge, 2019.

4 Green, C. Shawn, and Aaron R. Seitz. “The Impacts of Video Games on Cognition (and How the Government Can Guide the Industry).” Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2, no. 1 (2015): 101–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732215601121.

5 Maxis. The Sims: Makin’Magic. Dragon Age Inquisition. Electronic Arts & Aspyr Media (PC Windows, Mac), 2003.

6 Ruckenstein, Michael. “Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture.” In Leisure and Ethics: Reflections on the Philosophy of Leisure, edited by Gerald S. Fain, 237–44. Oxon Hill, MD: American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 1991.

5 C. Shawn Green and Aaron R. Seitz, “The Impacts of Video Games on Cognition (and How the Government Can Guide the Industry),” Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2, no. 1 (2015): 101–10.

“Herbas quod ad maleficas pertenit.” Magic and Historical Settings in the Tabletop Roleplay Game1

THOM GOBBITT, INSTITUT FÜR MITTELALTERFORSCHUNG, AUSTRIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES (OEAW), VIENNA | @BOOKSOFLAWMy main focus in this paper is how magic and the historical setting relate to the oldest written Lombard laws, the Edictus Rothari (issued in 643 CE), and how to incorporate these in a historically-informed, playable and educational way into tabletop roleplay games (TTRPG).2 Magic and supernatural creatures appear directly in four of the laws from the Edictus Rothari, and we can clearly see Lombard law-givers imagining and responding to this magic or, at least, responding to behaviours inspired by the early medieval magical beliefs and customs of the Lombard people. While the contents of these laws offer wonderful plot-hooks, and will surely spark ideas for characters and scenes, story arcs or even a full campaign, the question arises: How do we incorporate this explicitly magical element as reflected in the laws into a role-play game that is firmly set in the history of our own world? Afterall, the question of whether or not magic is real may seem, to the modern sceptic, to have an obvious, negative answer. But such a simplistic response overlooks the far more interesting questions of did early medieval Lombards and/or law-givers think that magic was real, and if so, how do we incorporate that magical thinking into our stories?

The snippet of law cited in the title to this chapter addresses the situation when a camfio [judicial duel], is being fought to determine whether an accusation is true or false, and one of the fighters is accused of having “herbs that pertain to maleficia [evil magic, witchcraft]” concealed upon him.3 While most early medieval magic involving herbs involves preparations that are drunk or sometimes ointments to be smeared on the body,4 here it is imagined that the herbs would just be carried. The power of the maleficent herbs can be made real in the game - and from a purely mechanical perspective, making magic real is as easy as a stroke of the pen and a roll of the dice. These herbs can gain their magical power simply through applying mechanisms in the TTRPG rules: in D&D terms, for instance, just by allowing the player to roll with advantage. And while that might be the difference between rolling success or a failure, a little dramatic licence can make the magic apparent too, perhaps the herbs start smouldering and unleash a putrid stench? Conversely, if we were to depict a judicial duel in a

1 This paper can be viewed in its original format here: https://twitter.com/booksoflaw/status/1666407154658553857.

2 Underlying this research, although not explored explicitly here, is my slowly on-going project in which I am developing a TTRPG set in the seventh-century Lombard laws and legal imagination, the Langobard RPG.

3 Edictus Rothari, §368. Emended translation based on: Katherine Fischer-Drew, trans., The Lombard Laws (Cinnaminson, N.J.: Penn: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1973).

4 Marianne Elsakkers, ‘Abortion, Poisoning, Magic and Contraception in Eckhardt’s Pactus Legis Salicae’, Amsterdamer Beiträge Zur Älteren Germanistik 57 (2003): 251–67; Valerie I.J. Flint, The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991), 236–37.

TTRPG setting with no magic at all, then from a purely sceptical perspective we can simply say that the fighter’s concealed herbs have no mechanical effect.

But how then, do we incorporate magical thinking into the game in a way that will lead players to engage with it or even employ it themselves? Mechanical encouragement via the rule system itself doesn’t only have to be in literal effects and bonuses or penalties to dice-rolls but can also come through the reward of experience points to players who roleplay it. And the storyteller can simply also just put it out there, reminding players of the content of the laws (and the potential for experience points), or putting the ideas into the mouths of the non-player characters (NPCs) then, whether the player characters (PCs) respond by accepting or rejecting the magical explanation for events, magic is nevertheless being discussed.

I would argue, though, that the question of whether to make magic actually real or not is only of secondary importance: far more interesting is the question of how magic can be used as a spark for role-playing and shaping the plot and setting. Moreover, the documentary evidence of the laws suggests that while some Lombards both believed in magic and behaved accordingly - others sought to restrict and restrain that belief.

Let us turn our attention to the magical entities of the striga, called a masca in the Langobardic language, and while the word would later come to mean “witch”, here refers to something more like a vampire.5 Two laws address accusations, whether made in anger or in certainty, that a free woman or girl was a striga, with the emphasis on the insult to her and her family.6 However, when the accused was much further down the social ladder, an enslaved or half free woman, the law addressed the situation where she had been killed:

No one may presume to kill another man’s aldia [half-free woman] or ancilla [enslaved woman] as if she were a striga [vampire], which the people call masca, because it is in no wise to be believed by Christian minds that it is possible that a woman can eat a living man from within.7

Superstitious belief in monsters stalking the night, the law argues, goes against the rationality and faith of good Christian thought. Nevertheless, the corollary to the rational and devout disbelief that such monsters did not exist, is the implication that at least some Lombards knew they did - and acted accordingly. And as storytellers we can make the striga (seem) real, and a story arc unfurls where in one chapter our protagonists must identify and dispose of such a creature, then in the next face the legal consequences and maybe even fight a duel to prove their truth. Oh, the champion for the king’s court is known to be a pretty good fighter - perhaps concealing some witch’s herbs inside your tunic before the fight begins would be a good idea and help tip the balance in your favour?

5 Jeffrey Burton Russell, Witchcraft in the Middle Ages (Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 1972), 50.

6 Edictus Rothari, §197-98.

7 Edictus Rothari, §376

The Middle Ages in Modern Games, 2023 Conference Proceedings Vol. 4 27

Bibliography

1 Burton Russell, Jeffrey. Witchcraft in the Middle Ages. Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press, 1972.

2 Elsakkers, Marianne. ‘Abortion, Poisoning, Magic and Contraception in Eckhardt’s Pactus Legis Salicae’. Amsterdamer Beiträge Zur Älteren Germanistik 57 (2003): 251–67.

3 Fischer-Drew, Katherine, trans. The Lombard Laws. Cinnaminson, N.J.: Penn: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1973.

4 Flint, Valerie I.J. The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991.

New Approaches to Real and Imagined Medievalisms

How to Navigate a Pandemic? A Plague Tale:

Innocence as a case study for exploring the intersection of medieval fiction, modern gaming and contemporary events1CAROLIN GLUCHOWSKI, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD | @CARIGLUCHOWSKI

Transcending Temporal Boundaries: Symbolic Representations of Plagues in 'A Plague Tale: Innocence' and Their Historical Contexts

In the realm of video games, 'A Plague Tale: Innocence', a 2019 action-adventure stealth game, serves as an apt lens to examine how societies remember medieval and modern plagues and pandemics.2 At the core of my exploration is the hypothesis that within the collective memory of plagues and pandemics, symbols assume paramount importance, as they articulate the intangible and abstract, making the absent present.

‘A Plague Tale: Innocence’: Navigating the Horrors of Historical France

The plot of the award-winning game ‘A Plague Tale: Innocence’ revolves around the orphaned siblings Amicia and Hugo as they brave the horrors of 14th century France. Journeying through the grim terrains of 14th-century France, Amicia and Hugo face the dual threat of plague-infested rats and the relentless French Inquisition.

From Intangible Disease to Tangible Threat: The Symbolism of Rats

In ‘A Plague Tale: Innocence’, rats serve as potent symbols, transforming an otherwise elusive disease into an immediate threat. The rodents spread a fatal disease known as‘the Bite’ and overt nod to the Black Death. According to game director Kevin Choteau, rats represent the “embodiment of the plague”, tapping into our innate aversion to these animals.3 In the game, it is hard to evade this omnipresent threat. At times, player witness a staggering 5,000 rats raiding their screens4 a hellish nightmare!

1 This paper can be viewed in its original format here: https://twitter.com/CariGluchowski/status/1666716447173668864

2 Asobo Studio. A Plague Tale: Innocence. Focus Home Interactive (PC Windows, PlayStation, Xbox), 2019.

3 Darragh Cooney, “Death, Disease, Terror; ‘A Plague Tale: Innocence’ Launches,” GamEir, May 14, 2019. Accessed 31 August 2023. https://gameir.ie/news/deathdisease-terror-a-plague-tale-innocence-launches.

4 Giancarlo Valdes, “How ‘A Plague Tale: Innocence’ Makes Diseased Rats so Terrifying,” Variety Daily, June 19, 2018. Accessed 31 August 2023.

https://variety.com/2018/gaming/features/a-plague-tale-innocence-interview1202850698/

Rats and the Black Death: Unravelling the Tangled Threads of History

When from c. 1346 to 1353 the Black Death spread through Europe and North Africa, “50 million from a population of roughly 80 million”people lost their lives.5 Medieval doctors attributed the disease to a “great pestilence in the air”.6 An official report from the medical faculty in Paris presented to Philip VI of France (1293–1350) suggested that the corruption of the air resulted from an unusual conjunction of three planets in 1345. The experience of death persisted in art and literature for an extended period, for example in the allegoric Dance of Death 7

By the late 19th century, rats had come to be linked with the Black Death. During an outbreak in Hong Kong, the Swiss-French physiologist Alexandre Yersin (1863–1943), a pupil of Louis Pasteur (1822–1895), co-discovered the bacillus responsible for the disease (Yersinia pestis). He demonstrated the presence of this bacillus in rodents, positing them as main transmission agents.8 In 1898, building on this work, French physician Paul-Louis Simond (1858–1947) proposed that the disease was transmitted to humans through fleas (specifically, Xenopsylla cheopsis) that had fed on infected rats. However, recent scholarship offers a slightly nuanced perspective, suggesting that rats may not have been the main transmitters. Instead, human ectoparasites are believed to have played a pivotal role in a more complex transmission chain.9 This intricate understanding of transmission, however, poses challenges when being adapted into a gripping game storyline.

Masks: Concretizing the Intangible of the COVID-19 Era

'A Plague Tale: Innocence' was announced in 2017 and launched in 2019, preceding the COVID-19 outbreak by only a few months. This chronological proximity has prompted some to interpret ‘A Plague Tale: Innocence’ in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. On 30 January 2020, the WHO declared the outbreak a public health emergency, an emergency that lasted until 5 May 2023.10 Unarguably, the face mask emerged as the most iconic symbol of the COVID-19 pandemic. In the many countries, face masks became mandatory at some point. Data from Statistica highlights the dramatic spike in global mask sales, increasing

5 John Kelly, Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, The Most Devastating Plague of All Time (New York, NY: HarperCollins, 2005); Jon Arrizabalaga, “The Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages,” in Plague and Epidemics, ed. Robert E. Bjork (London, England: Oxford University Press, 2010)

6 Rosemary Horrox, The Black Death, ed. Rosemary Horrox (Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 1994), 157; Carl S. Sterner, “A Brief History of Miasmic Theory,” 2007. Accessed 31 August 2023.

http://cssterner.nfshost.com/research/files/History_of_Miasmic_Theory_2007.pdf

7 André Corvisier, Les danses macabres (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France - PUF, 1998); Anna Louise DesOrmeaux, “The Black Death and Its Effect on 14th and 15th Century Art” (Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, 2007).

8 Georges-Félix Treille and Alexandre Yersin, “La Peste Bubonique à Hong Kong,” VIIIe Congrès International d’hygiène et de Démographie, 8 (September 1894): 662–67.

9 Katharine R. Dean et al., “Human Ectoparasites and the Spread of Plague in Europe during the Second Pandemic,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115, no. 6 (2018): 1304–9, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1715640115.

10 “Corona Virus (COVID-19) Cases and Dashboard.” World Health Organization. Accessed 31 August 2023 https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c

from $12.9 billion in 2019, primarily catering to medical professionals, to an astonishing $378.9 billion in 2020.11 Fascinatingly, shortly after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, face masks began to feature prominently in art. Their representations ranged from light-hearted memes to profound statements, marking an indelible imprint on art history. Drawing inspiration from revered Western art traditions, this phenomenon recontextualised these artworks against the stark reality of the COVID-19 era. Such artistic endeavours underscored the mask's cultural significance during the pandemic, simultaneously highlighting the poignant losses experienced the diminished human connections and altered engagements with art and culture.

Conclusion

'A Plague Tale: Innocence' catalyses a broader reflection on symbolic representations of pandemics across eras. As I submit this piece for MAMG23, I envision it as a springboard for deeper dives into this fascinating interplay of history, symbolism, and memory.

Bibliography

1 Arrizabalaga, Jon. “The Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages.” In Plague and Epidemics, edited by Robert E. Bjork. London, England: Oxford University Press, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1093/acref/9780198662624.001.0001

2 Asobo Studio. A Plague Tale: Innocence. Focus Home Interactive (PC Windows, PlayStation, Xbox), 2019.

3 Cooney, Darragh. “Death, Disease, Terror; ‘A Plague Tale: Innocence’ Launches.” GamEir, May 14, 2019. https://gameir.ie/news/death-diseaseterror-a-plague-tale-innocence-launches/

4 Corvisier, André. Les danses macabres. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France - PUF, 1998.

5 Dean, Katharine R., Fabienne Krauer, Lars Walløe, Ole Christian Lingjærde, Barbara Bramanti, Nils Chr Stenseth, and Boris V. Schmid. “Human Ectoparasites and the Spread of Plague in Europe during the Second Pandemic.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115, no. 6 (2018): 1304–9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1715640115.

6 DesOrmeaux, Anna Louise. “The Black Death and Its Effect on 14th and 15th Century Art.” Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, 2007.

7 Horrox, Rosemary. The Black Death. Edited by Rosemary Horrox. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 1994.

8 Kelly, John. Great Mortality: An Intimate History of the Black Death, The Most Devastating Plague of All Time. New York, NY: HarperCollins, 2005.

9 Richter, Felix. “Global Mask Sales Surged 30-Fold during the Pandemic.” Statista, January 12, 2023. https://www.statista.com/chart/29100/globalface-mask-sales/

11 Felix Richter, “Global Mask Sales Surged 30-Fold during the Pandemic,” Statista, January 12, 2023. Accessed 31 August 2023.

https://www.statista.com/chart/29100/global-face-mask-sales/

10 Sterner, Carl S. “A Brief History of Miasmic Theory.” 2007 http://cssterner.nfshost.com/research/files/History_of_Miasmic_Theory_20 07.pdf.

11 Treille, Georges-Félix, and Alexandre Yersin. “La Peste Bubonique à Hong Kong.” VIIIe Congrès International d’hygiène et de Démographie, 8 (September 1894): 662–67.

12 Valdes, Giancarlo. “How ‘A Plague Tale: Innocence’ Makes Diseased Rats so Terrifying.” Variety Daily. June 19, 2018. https://variety.com/2018/gaming/features/a-plague-tale-innocenceinterview-1202850698/.

13 World Health Organization. “Corona Virus (COVID-19) Cases and Dashboard.” https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c.

“Non si può guarire.” An (idea)historical approach to Plague Games and death in the streets1

PETER FÄRBERBÖCK, PARIS LODRON UNIVERSITY, SALZBURG | @NOMINIEL ASKA MAYER, TAMPERE UNIVERSITY, TAMPERE

“We cannot be cured, we all must die!”2

With this line, the historical song Homo Fugit Velut Umbra pronounces the fatality of experiencing the European plague, bringing to sound the manifold visual depictions of plague and suffering in urban environments by baroque painters. The message of these baroque examples of Plague Art is as simple as it is intense: No one can escape the pandemic death.

Within the following text, we will trace the idea-historical continuum of this message from the art of late mediaeval times to the contemporary digital game. Contextualized within the concept of neo-baroque, as established by Calabrese3 and Ndalianis4, we will introduce the depiction of death and critical shifts of established societal structures and present the specific relevance of the spatial trope of streets and its relation to the messages of Plague Art and Games.

By relating Plague Art with contemporary Digital Games, we do not only present a reemergence of historical patterns of representation, but also in the spirit of Ndalianis attempt to develop a “clearer understanding of the significance of (contemporary) cultural objects and their function” by examining their past counterparts.5

A (Very) Short Introduction to Neo-Baroque

Before exploring the various depictions of plague related death, we want to provide a short introduction into the theoretical framework of Neo-Baroque and its relation to digital games 6

1 This paper can be viewed in its original format here: https://twitter.com/Nominiel/status/1666724271945576448

2 Orig.: “[...] non si può guarire, bisogna morire.” Anonymous Composer, “Homo fugit velut umbra (Passacaglia della Vita),” in Canzonette spirituali, e morali, che si cantano nell’Oratorio di Chiavena, eretto sotto la protettione di S. Filippo Neri. Accommodate per cantar à 1. 2. 3. Voci come più piace, con le lettere della chitarra sopra arie communi, e nuove date in luce per trattenimento sprituale d’ogni persona [Musica a stampa], ed. by Filippo Neri (Milano: Carlo Francesca Rolla Stampatore vicino al Verzaro, 1657), 14-15.

3 Omar Calabrese, Neo-Baroque. A Sign of Times (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992).

4 Angela Ndalianis, Neo-Baroque Aesthetics and Contemporary Entertainment (London: The MIT Press, 2004).

5 Ndalianis, Neo-Baroque Aesthetics, 6.

6 Due to the format of this work, we can here only provide a very short glimpse into neo-baroque structures and their appearance in digital games. For a more detailed insight, we would like to point towards the already referenced Ndalianis’ Neo-Baroque and the recent perspective of Mayer’s Crisis Play. See: Aska Mayer, Crisis Play. Perceptions and didactics of states of crisis in digital games as a neo-baroque phenomenon (Espoo: Aalto University, 2023).

The Middle Ages in Modern Games, 2023 Conference Proceedings Vol. 4 34

Based on the understanding of the baroque as a cultural phenomenon constituted by its intensity and its norm-breaking and spectacular nature as mass media, Ndalianis and Calabrese recognize similar structures and concepts in between the historical works of art and contemporary digital games. In relation to the historical era, the neo-baroque is alongside other aspects defined by a fascination with the abnormal, audio-visual excessiveness and the (self)referentiality of media. While differently manifested in different forms of media, the neo-baroque concept is defined as a result and cultural expression of crisis experience.7

Death in the streets

Throughout the plague and besides several other saints and martyrs, St. Roch was typically venerated as a patron saint, based on his hagiography, which states that he cared for the plague-ridden, whereas he himself was not helped at first. His own sickness is played out publicly in the streets.

This medieval imagery of public suffering and death can be found in baroque depictions as well, aesthetically intensified towards the extreme. As an example, Poussin paints under the influence of the Italian epidemic annus horribilis 1630 a biblical scenery of plague-induced despair and devastation.

The recurring motive of public suffering during times of plague responds to the class-dissolving Danse Macabre as evident in the earlier introduced Homo Fugit Velut Umbra. Suddenly no one is safe from dying outside of the presumed safety of their own home. The separation between classes deteriorates, the established system is abruptly crumpling.

These depicted crises become inherently apocalyptic. In the publicity and the sudden increase of death, the handling of the dead far from established funeral rites, the image of "negative cultural evolution" emerges.8 Here we recognize a link to the stereotypical medievalism of several digital games, depicting the fictionalized historicity as an age of non-knowledge.

Appeal in Image and Play

This past depiction of a dissolving societal system through a new form of dying not only amplifies an awareness of death, but also serves a morbid curiosity, a fascination with decaying structures, which motivates both historical and contemporary consumption.9

7 Mayer, Crisis Play, 71.

8 Christian Hoffstadt, “‘Davon geht die Welt nicht unter…' Mediale Vermittlung von Katastrophen zwischen Fiktionalität und Faktizität,” in Abendländische Apokalyptik: Kompendium zur Genealogie der Endzeit, ed. by Veronika Wiesner (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2013), 280.

9 Anna Louise DesOrmeaux, “The Black Death and Its Effect on 14th and 15th Century Art” (Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, 2007), 29.

The Middle Ages in Modern Games, 2023 Conference Proceedings Vol. 4 35

Figure 1. Anonymous Artist, Hl. Rochus erkrankt an der Pest [St. Roch falls ill with the plague], 14801520, painting on wood, 67x50 cm. Regensburg, Museum der Stadt.

Figure 2 Nicolas Poussin, La Peste d’Asdod [The Plague of Ashdod], 1630-31, oil on canvas, 148x198 cm. Paris, Louvre.

Figure 1. Anonymous Artist, Hl. Rochus erkrankt an der Pest [St. Roch falls ill with the plague], 14801520, painting on wood, 67x50 cm. Regensburg, Museum der Stadt.

Figure 2 Nicolas Poussin, La Peste d’Asdod [The Plague of Ashdod], 1630-31, oil on canvas, 148x198 cm. Paris, Louvre.

The Middle Ages in Modern Games, 2023 Conference Proceedings Vol. 4 36

Besides the reappearance of abundant baroque imagery and a morbid motivation within plague medievalisms in digital games, we can additionally locate a further conceptual similarity, the emphasis on an appeal to the viewers or player.

Already hinted in the depiction of St. Roch, continued through Poussin’s painting and finding its contemporary appearance in games like A Plague Tale: Innocence10 or The Last of Us11 this appeal is a two-fold one: the threat is not only within the plague, but streets and journeys are presented as spaces of danger.

In similar fashion as its historical counterparts A Plague Tale not only presents the aftermath of the dangers of the streets and the nearly complete erosion of society, but further points out these threats to contemporary players as a warning.

The Last of Us further intensifies these tropes, brutally ballooned into a dark medievalist show of violence. While instead of a historicized setting, the game is set in an (im)possible future, the barbarity, ruined streets, constant death and dirt are still constituting a plague-related medievalism, presenting a warning to society.

While this reading might suggest a perpetual continuum throughout (art)history, we suggest an understanding of these manifestations of plague iconography as a post-modern crisis-driven intensification of these tropes and experiences 12

While the historical plague art functions as a revealing warning and reaction, the digital game is additionally emphasising on the aspect of morbid curiosity and intensifies the experience of the fictional crisis through its multi-sensory qualities and the absurdly heightened explicitness of apocalyptic narratives as present in The Last of Us. And even further, the digital narrative points towards the future, as it is no longer a momentary depiction of decay, but typically presents an attempt to newly arise from the collapsed structures, as defined as a key-element of the uncertain neo-baroque times by Ndalianis. The worst is yet to come.

Bibliography

1 Anonymous Artist. Hl. Rochus erkrankt an der Pest. 1480-1520, painting on wood, 67x50 cm. Regensburg, Museum der Stadt Regensburg.

2 Anonymous Composer. “Homo fugit velut umbra (Passacaglia della Vita).” In Canzonette spirituali, e morali, che si cantano nell’Oratorio di Chiavena, eretto sotto la protettione di S. Filippo Neri. Accommodate per cantar à 1. 2. 3. Voci come più piace, con le lettere della chitarra sopra arie communi, e nuove date in luce per trattenimento sprituale d’ogni persona [Musica a stampa], edited by Filippo Neri, 14-15. Milano: Carlo Francesca Rolla Stampatore vicino al Verzaro, 1657.

3 Asobo Studio. A Plague Tale: Innocence. Focus Home Interactive (PC Windows, Mac, PlayStation, Xbox), 2019.

10 Asobo Studio. A Plague Tale: Innocence. Focus Home Interactive (PC Windows, PlayStation, Xbox), 2019.

11 Naughty Dog. The Last of Us. San Mateo: Sony Computer Entertainment, PlayStation, 2013.

12 Ndalianis, Neo-Baroque Aesthetics, 19; Calabrese, Neo-baroque, 120.

4 Calabrese, Omar. Neo-Baroque. A Sign of Times. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992.

5 DesOrmeaux, Anna Louise. “The Black Death and Its Effect on 14th and 15th Century Art.” Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, 2007.

6 Hoffstadt, Christian. “‘Davon geht die Welt nicht unter…’ Mediale Vermittlung von Katastrophen zwischen Fiktionalität und Faktizität“. In Abendländische Apokalyptik: Kompendium zur Genealogie der Endzeit, edited by Veronika Wiesner. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2013. 273-311.

7 Mayer, Aska. Crisis Play. Perceptions and didactics of states of crisis in digital games as a neo-baroque phenomenon. Espoo: Aalto University, 2023.

8 Naughty Dog. The Last of Us. San Mateo: Sony Computer Entertainment, PlayStation, 2013.

9 Ndalianis, Angela. Neo-Baroque Aesthetics and Contemporary Entertainment. London: The MIT Press, 2004.

10 Poussin, Nicolas. La Peste d’Asdod [The Plague of Ashdod]. 1630-31, oil on canvas, 148x198 cm. Paris, Louvre.

Spatial, Simulated, and Mental Medievalisms

The Virtual Pilgrim: A Study of Mental Travel in Pentiment1

Fantasy worlds are incredibly potent vectors for self-reflection. Such a concept is integral to the medieval notion of mental pilgrimage, where the self is immersed in an imagined place created by the mind in order to access otherwise inaccessible locations. In this process, the real location is subverted by notions of the ideal, transforming it into a locus for powerful emotional and spiritual reflection. In Pentiment, the 2022 game by Obsidian Entertainment, the main character Andreas Maler utilizes such notions to explore the repercussions of player choices made in the course of the game.2

The narrative, heavily inspired by Umberto Eco’s 1980 novel The Name of the Rose (Il nome della rosa), tracks the story of an illuminator named Andreas Maler from 1518 to about 1543 during the tumultuous spread of Reformation ideals across Upper Bavaria. The game employs a form of mental pilgrimage as a method of player engagement, designed to get the player to reflect on the choices they’ve made throughout the game. Like Maler, the player is forced in these vignettes to contemplate notions of justice and duty: Maler in his Memory Palace, the Player in the game itself.

One of the main mechanisms throughout the game are sleep interludes where the player visits Maler’s Memory Palace (MP) to contemplate decisions both made or neglected, and those on the horizon. The player visits the imaginary palace in two stages first by boat, then by maze. When the player approaches the Memory Palace, it appears as a walled, round city. In the centre is a domed, two-story circular building, whose entrance is aligned with that of the city walls. The

1 This paper can be viewed in its original format here: https://twitter.com/BlairApgar/status/1666856395805798400

2 Obsidian Entertainment. Pentiment, Xbox Game Studios (PC Windows, Xbox), 2022.

depiction is remarkably similar to medieval illustrations of Jerusalem, particularly those found in pilgrim guides such as the twelfth century Gesta Francorum or on maps such as those found in the Chronica Majora.3

To enter the Memory Palace, the player must solve a labyrinth. As you manoeuvre around the maze, you are confronted with questions regarding Maler's relationship with his family and his involvement with the town’s affairs, posed by the very people whose expectations seem to haunt Maler.

These dialogue vignettes are sudden and confrontational, asking the player to consider their actions; they become more interrogative with each iteration of the maze. Later play-throughs reveal that movement and dialogue is inextricably linked, regardless of the path taken.

Initially, the maze shape invokes the utopic city of the Renaissance a walled city with concentric rings, the Memory Palace as the organizational centre 4 This visual connection weakens with each visit: the maze becomes less ideal while the MP falls into visible disarray and chaos. However, as notions of the ideal begin to fade aligning perfectly with the character’s own growing cynicism the algorithmic convolution of the maze becomes more prominent. The player’s interaction becomes more intentional as the path forward is increasingly obscured.

Each new obfuscation forces the player to further linger on the narrative implications of their choices. This mechanism is similar to the imaginative and meditative processes used throughout the medieval material culture of pilgrimages.

3 Jay Rubenstein, ‘Heavenly and Earthly Jerusalem: The View From Twelfth-Century Flanders’, in Visual Constructs of Jerusalem, ed. Bianca Kühnel, Galit Noga-Banai, and Hanna Vorholt, vol. 18, Cultural Encounters in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages (Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2014), 268–69, https://doi.org/10.1484/M.CELAMAEB.5.103083.

4 Horst de la Croix, ‘Palmanova: A Study in Sixteenth Century Urbanism’, Saggi e Memorie Di Storia Dell’arte 5 (1966): 40–41.

Though mazes were not the exclusive purview of medieval Christians, the backdrop of the Abbey of Kiersau complete with its own pilgrimage shrine and the parish church dedication (‘Our Lady of the Labyrinth’), provides persuasive evidence for this framework. Daniel K. Connolly has written on the power and significance of mazes to medieval pilgrims who engaged them as imagination devices. Connolly links the pavement labyrinth at Chartres to contemporaneous depictions of Jerusalem such as those in ‘Situs Hierusalem’ maps.5

The repetitive, inwards movement invoked the centrality both spiritually & mentally of the holy city to the visiting pilgrim. Every turn oriented them towards a different view of the cathedral, prompting different modes of reflection much like the game, movement mattered.

As the game progresses and the maze becomes more maze-like (thus arguably reverting to a more ‘medieval’ form), it reflects the larger narrative theme which sets modernity and tradition at odds. The game’s emergent Reformation which threatens the closure of the Abbey; the pagan origins of the town, abandoned and obscured in fear of the Inquisition; even the very style of the game itself which brings the illuminated manuscript into the digital age. Thus, by utilizing a boldly medieval imagination device, the game subtly advances a case in which modernity does not inevitably win out but struggles against the strength and allure of tradition. Furthermore, it marries a medieval tool for imagination with a modern one the video game.

Bibliography

1 Connolly, Daniel

The Middle Ages in Modern Games, 2023 Conference Proceedings Vol. 4 42

Northern Europe and the British Isles, edited by Sarah Blick and Rita Tekippe, 285–314. Boston: Brill, 2005.

2 . ‘Imagined Pilgrimage in the Itinerary Maps of Matthew Paris’. The Art Bulletin 81, no. 4 (1999): 598–622. https://doi.org/10.2307/3051336.

3 Croix, Horst de la. ‘Military Architecture and the Radial City Plan in Sixteenth Century Italy’. The Art Bulletin 42, no. 4 (1960): 263–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/3047915.

4 . ‘Palmanova: A Study in Sixteenth Century Urbanism’. Saggi e Memorie Di Storia Dell’arte 5 (1966): 23–179.

5 Obsidian Entertainment. Pentiment, Xbox Game Studios (PC Windows, Xbox), 2022.

6 Rubenstein, Jay. ‘Heavenly and Earthly Jerusalem: The View From TwelfthCentury Flanders’. In Visual Constructs of Jerusalem, edited by Bianca Kühnel, Galit Noga-Banai, and Hanna Vorholt, 18:265–76. Cultural Encounters in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1484/M.CELAMA-EB.5.103083.

Imagining Futures

Past: Reading Fallout for its Influence on the Medieval in Rhetorical and Literary Studies

1

Post-apocalyptic games are useful to teachers of writing and multimodal textuality for how they tend to explore operations of cultural memory. By thinking through “the end of the world,” students can reconsider the ideological substructures of social life. Fallout 4, Bethesda Game Studios’ popular 2015 open-world role playing game, is set hundreds of years after a nuclear war devastated the planet and divided history into two discrete periods: before and after the bombs.2 While the game’s title most clearly pertains to the physical sequelae of nuclear Armageddon, it also figuratively references the aftereffects of near-total social collapse. How might survivors of the apocalypse conceptualize progress without a linear connection to the past? In offering possible answers to this question, Fallout 4 is an effective teaching tool in both rhetoric and literature classrooms. Despite its futuristic setting, the game calls the medieval to mind in several ways, most notably in the neo-chivalric Brotherhood of Steel faction. These “knights” and “squires” battle the monsters of mythos that have become lived reality for the inhabitants of the wasteland. The game’s post-apocalyptic ludonarrative invokes a myriad of antiquarian aesthetics from bygone eras, enabling students to see from a distance–both in terms of time and identification–how conceptualizations of the past are necessarily mediated by the present.

Moreover, students of writing benefit from assuming new character identities, as in ancient Roman prosopopoeia exercises (speeches in the voice of a figure or object). Fallout 4 acts as a site in which students can experiment with projective identities and learn as their characters.3 Fallout 4 is especially ripe for immersive experience. Unlike earlier Fallout games in which the player assumes the identity of a wastelander familiar with the nuclear Armageddon and social collapse following the global“Great War,”Fallout 4’s opening sequence violently wrests the player-character from an idyllic retrofuturistic suburban Boston into a postnuclear wasteland inhabited by radioactive, mutated creatures. The Fallout 4 player’s experience more closely matches that of the character’s, as both player and character take part in the communal apocalyptic experience. In Gee’s terms, the player and the character form a projective identity where the player’s goals and aspirations, as well as their knowledge of our (aka the‘real’) world can be cast onto the character. Students can participate in this identity-building project within the context of literary and rhetoric study. Having survived the end of the world, the student participates in the wasteland’s larger project of reimagining the lost past.

1 This paper can be viewed in its original format here: https://twitter.com/AlicenDavis3/status/1666859354140684316

2 Bethesda Game Studios. Fallout 4. Bethesda Softworks (PC Windows, PlayStation, Xbox), 2015.

3 James Paul Gee, What Video Games Have to Teach Us about Learning and Literacy, 2nd ed. (Gordonsville, VA: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008).

Through playing Fallout 4, students engage with factions who appropriate the iconography and language of historical groups in the service of reconstruction: e.g., the Brotherhood of Steel uses ranks of paladin, knight, and squire; the Minutemen present themselves as an American Revolutionary militia; the Railroad references the Underground Railroad. Even the central hub of the map, Diamond City– a repurposed Fenway Park–is a monument to pre-war baseball.

In one example, the player can engage with non-player character Moe Cronin’s misunderstanding of what baseball was like before the war: “One team would beat the other team to death with things called Baseball Bats… True fact!” This interaction demonstrates how encounters with history are necessarily filtered through the perspective of the current moment. As with medievalism, nostalgic aesthetics forge a fantasy of immediate connection to the past. Without access to the “world-before,” Cronin’s ideology constructs a history of baseball that is framed by his own culture’s overtly violent priorities.

The game also presents a multifaceted approach to how it deals with the past, particularly in its illustration of highly stylized mid-century decor becoming subject to nuclear ruin. Kathleen McClancy argues of the Fallout world that this retrofuturistic image acts as a kind of mask that enables critiques of American Cold War policy and sentiment.4 But where the setting looks retrofuturistic to critique an aspect of American life, its post-nuclear “return” to medieval social structures like agrarianism and quasi-feudalism, Fallout 4 comments that our separation from and memory of the past is, more generally, problematic.

Students in the classroom know what the current world is like, and it is very unlike the world of Fallout on several levels. But when students play through the preand-post-War sequences of Fallout 4, they can identify with both the suburbanite and the wastelander as they encounter two reconstructed images of the past: one hyper-consumerist, one medieval.

When student-players take on new identities in the game, they confront the epistemic anxiety of the post-apocalypse. Players become complicit in the appeals to nostalgia employed among the game’s factions in response to overwhelming collective trauma. Then, having learned from the nuanced world of Fallout 4, students can complete writing projects such as defence of action speeches, reflections, justifications, and analyses, all of which contribute to success in and beyond rhetoric and literature classrooms. With active and deep genre ecologies, each of these forms of writing can draw on the game-world and the students’ real-world experience. Research papers might address issues examined within the gamespace, or students might react to the anti-Communist rhetoric that they see within Fallout 4’s post-nuclear Boston. Then, having done work in the classroom using the game as a site or as an example of how rhetoric or literature operate, they become able to transfer this skillset to the environment we share in the real world.

Using apocalyptic video games, teachers of writing can prime students, through their projective and real identities, to write for issues that they will encounter beyond the classroom, such as selective nostalgia, created histories, and fraught

4 Kathleen McClancy, “The Wasteland of the Real: Nostalgia and Simulacra in Fallout,” Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research 18, no. 2 (September 2018), https://gamestudies.org/1802/articles/mcclancy.

The Middle Ages in Modern Games, 2023 Conference Proceedings Vol. 4 45

relationships to the past. Fallout 4 is especially useful for this project in that it critiques how historical eras like the Cold War and Middle Ages are mythologized in popular imagination.

Bibliography

1 Bethesda Game Studios. Fallout 4. Bethesda Softworks (PC Windows, PlayStation, Xbox), 2015.

2 Gee, James Paul. What Video Games Have to Teach Us about Learning and Literacy. 2nd ed. Gordonsville, VA: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

3 McClancy, Kathleen. “The Wasteland of the Real: Nostalgia and Simulacra in Fallout.” Game Studies: The International Journal of Computer Game Research 18, no. 2 (September 2018).

https://gamestudies.org/1802/articles/mcclancy

Simulating History in Assassin’s Creed Valhalla1

SHAWN GILMORE, UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS | @GIPPERFISHIn the Assassin’s Creed franchise, period-set worlds simulate “real” historical locations, people, and events. In Assassin’s Creed Valhalla, players control Layla Hassan, who controls Eivor Varinsdottr, a 9th-century CE Viking who travels from Norway to England and beyond, eventually to the Americas.2 To inhabit her ancestor Eivor, Layla enters the Animus, which creates a simulation of Eivor’s life and world, hoping to find information buried by “official” histories in the hopes of tipping the scales in a long-running war between the Assassins and Knights Templar. Assassin’s Creed games present a symbolic history, as well as a new origin for humanity, ancient Orders and their opponents, and discrepancies from documented history (with a helpful in-game Codex), simulated so the in-game protagonist can find powerful artifacts, Apples of Eden.