12 minute read

Photographs Lead Ethiopian Writer to Hidden Story of Women

from The Voice magazine

Photographs Lead Ethiopian Writer to Hidden Story of Women During War

Before writing her most recent novel, Maaza Mengiste began researching the Ethiopian resistance in the 1935 invasion by Italian forces. She discovered photographs of women dressed in military clothing with weapons over their shoulders. She organized them by date and location. Mengiste soon began to gain an understanding of the conflict she never learned about in school. “These women decided to join in the front lines,” she told VOA. “I had never heard that story. And this is what really inspired me to continue this, because if I didn’t know it, and if a lot of other Ethiopians weren’t speaking about it, this means maybe that nobody really had been paying attention to this.” Mengiste found photographs of Ethiopian girls taken by Italian soldiers. Some photos were used to persuade men to join the conflict. Others were much darker and showed the horror of war. “They were taken by soldiers for fun, and they were passed around as jokes and as postcards to send home. And that was the side of war also that I wanted to show,” she said. The research led to her 2020 book, “The Shadow King.” It tells the story of Hirut, a mistreated girl who becomes the personal guard for a person claiming to be the exiled Ethiopian ruler Haile Selassie. The novel has won worldwide praise and was a top competitor for the Man Booker Prize. However, the honor went to another book. Mengiste’s book revisits part of forgotten history, said Lee Child. He is a writer of 24 novels and one of the judges for the 2020 Booker Prize. “The story is important, really, the opening shots of the Second World War, but rarely told before,” Child said in a video discussing the novel. “Its place on the shortlist merely confirms its status as one of the great novels of the year.” Mengiste was born in Ethiopia in 1971. Her family left the country when she was 4 years old. They lived in Nigeria and Kenya before moving permanently to the United States. As a girl, she remembered moments of her first years in Ethiopia. But it was not until she was much older that she considered writing them down. “I’m surprised I kept those memories, because I was very young,” she said. “But I think that the shock of what I experienced both in Ethiopia but also the migration was so intense and so deep that everything froze for me and stayed inside. And so, I would keep coming back.” Mengiste’s parents did not immediately welcome her decision to become a writer. But she felt she had stories to tell. She believes other Ethiopians feel the same but may not have a way to share their stories with the world. Mengiste said that history and literature across East Africa is told through spoken word. “I think all of us remember those moments when we are sitting around at a dinner table or sitting having a meal and someone starts a story. And the entire room moves in that direction. Everyone is laughing, or people are crying. That’s a book inside a human being. And my inspirations came from my relatives. Some of them didn’t go to school.” Now, Mengiste wants to help new authors. She has helped produce a collection of stories by 14 Ethiopian writers called Addis Ababa Noir. She believes there is a lot of talent that could be shared with more people with the help of translators and publishing companies. I’m Jonathan Evans.

Advertisement

British lawyer Karim Ahmad Khan, who represented Kenya’s deputy president William Ruto at the International Criminal Court (ICC), will take over from current ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda in June 2021 we can officially confirm his appointment as the new Chief Prosecutor to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague, The Netherlands. The election of the 51-year-old lawyer took place on 12th February 2021 to settle the process of finding the Hague-based court’s third Chief prosecutor, which begun in 2019 and dragged through 2020 and early 2021 as the assembly of state parties failed to agree on a candidate by consensus. Both Fatou Bensouda, a Gambian who had previously served as the court’s deputy prosecutor since 2004, and her predecessor, Argentine lawyer Louis Moreno Ocampo, were elected by consensus. Khan was instead elected via secret ballot, after intense lobbying from both the United Kingdom and Kenya, according to reports reaching our newsroom. No consensus The lack of consensus around Khan until the final vote, where he got 72 votes – 10 more than what he would have needed to win was partially due to his extensive work as an international criminal lawyer. Several East African NGOs lobbied against his election, focusing primarily on the Kenya case, where he was lead counsel for Francis Muthaura, then head of the civil service

and prominent power broker in President Mwai Kibaki’s government, and later deputy president William Ruto. The NGOs accused him of contributing to the “deliberately tormented climate of political hostility” against the then ICC. As lead counsel for Deputy President Ruto, Khan gave several media interviews and made a brief speech at a political rally held after the cases ended in a mistrial in 2016. “He joined the bandwagon of those who were vilifying civil society, who were seeking justice, and those who were retraumatizing victims,” Njonjo Mue, a Kenyan human rights activist and lawyer wrote via the social media. Self-defence In the lead up to the February 2021 vote, Khan defended himself in an open letter addressing the gravest of the charges the civil society bodies made against him, concerning his silence on the December 2014 disappearance and murder of a “The responsibility to physically protect, relocate or support witnesses does not fall upon an individual counsel under the Rome Statute regime,” he wrote in the letter to the non-profit organization, Journalists for Justice (JfJ). He explained that he had made contact with Kenya’s criminal investigations department, but “ it was for the ICC-VWU [ICC’s Victims and Witness Unit] and not Counsel, to follow up with the Government of Kenya.” Since he was admitted to the bar in 1992, Khan has represented many prominent Africans facing international criminal charges. In addition to Kenya’s deputy president, his long list of former clients includes: • Charles Taylor (Liberia) • Abdallah Banda (Darfur, Sudan) • Bahar Garda (Darfur, Sudan) • Saleh Jamus (Darfur, Sudan)

• Said Al-Islam Gadaffi (Libya) • Jean-Pierre Bemba (Democratic Republic of Congo/Central African Republic) Conflicts of interest As the ICC’s prosecutor until June 2030, Khan will have to navigate the complications of being unable to prosecute some cases related to previous work, including investigations into witness tampering and intimidation in the collapsed Kenya cases. He will also navigate, like his predecessors, the political questions of the court’s focus on the African continent. All the cases brought to trial since the court’s inception have been of Africans, and of the 13 ongoing situations and/or investigations, only three – Bangladesh/Myanmar, Georgia and Afghanistan – are not African. Days before Khan’s election, the court said it had jurisdiction over crimes committed in Palestine, opening another political front that will pit Khan’s office against Israel, and its key allies. The Afghanistan investigations – which began in early 2020 and led the US administration of Donald Trump to place current prosecutor Bensouda and another top ICC official under economic and visa sanctions – could also make or break Khan’s credibility. In his open letter to the Journalists for Justice Organization (JfJ), Khan said that he has “thick skin and that resilience” necessary to do his job. But the prosecutor’s job at the ICC is both a political and legal role, as both his predecessors found out. The new prosecutor’s first tasks will include deciding the next steps on the probe into war crimes in Afghanistan and the hugely contentious investigation into the 2014 IsraelPalestinian conflict in Gaza. In a major decision last month, a pre-trial chamber of the ICC determined that The Hague has jurisdiction to open a criminal investigation into Israel and the Palestinians for war crimes alleged to have taken place in the West Bank, Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem, paving the way for a full investigation after a five-year preliminary probe opened by Fatou Bensouda. Bensouda indicated in 2019 that a criminal investigation, if approved, would focus on the 2014 Israel-Hamas conflict (Operation Protective Edge), on Israeli settlement policy and on the Israeli response to Hamas-led protests at the Gaza border. Israel and the United States neither of which are ICC members have strongly opposed the probe into alleged war crimes by both Israeli forces and Palestinian terrorist groups. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said of the ruling: “Today the ICC proved once again that it is a political body and not a judicial institution. The ICC ignores the real war crimes and instead pursues the State of Israel, a state with a strong democratic government that sanctifies the rule of law, and is not a member of the ICC.” “In this decision,” Netanyahu added, “the ICC violated the right of democracies to defend themselves against terrorism, and played into the hands of those who undermine efforts to expand the circle of peace. We will continue to protect our citizens and soldiers in every way from legal persecution.” The administration of then-US president Donald Trump hit Bensouda and another senior ICC official last year with sanctions including a travel ban and asset freeze over a probe that includes alleged US war crimes in Afghanistan. The Biden administration has signalled a less confrontational line but has not said whether it will drop sanctions against Bensouda, who has attacked the “unacceptable” measures. The ICC is the world’s only permanent war crimes court, after years when the only route to justice for atrocities in countries like Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia was separate tribunals. Hamstrung from the start by the refusal of the United States, Russia and China to join, the court has since faced criticism for having mainly taken on cases from poorer African nations. By the end of June 2021, the ICC would have a new Chief Prosecutor of the criminal court in person of Britain’s Karim Khan. He ousted Carlos Castresana of Spain, Ireland’s Fergal Gaynor and Italy’s Francesco Lo Voi to secure this top job but with his challenges ahead of him.

Exclusive: Angola moves to seize Dos Santos-linked asset in Dutch court

Angola has asked a Dutch court to hand over a halfbillion-dollar stake in the Portuguese oil company Galp linked to ex-first daughter Isabel Dos Santos, 2016 until 2017, when her father’s four-decade rule ended. Representatives for Isabel dos Santos, who lives outside Angola, did not reply to questions or comment on this

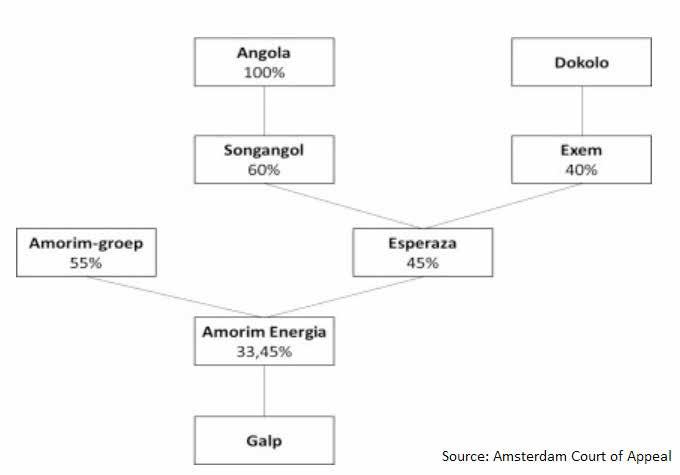

its lawyers told the press. Angola’s government says top officials under former president Jose Eduardo dos Santos took advantage of high oil prices in the last decade to spin a global web of business deals that led to their personal enrichment at the country’s expense. Battered by COVID-19 economic fallout and mired in foreign debt, Angola is seeking to recover assets it says were siphoned off. Its prime focus is Isabel dos Santos, the ex-president’s daughter, a business tycoon who became Africa’s richest woman. The legal bid for the Galp stake has not previously been reported. Dos Santos briefly ran state oil company Sonangol from matter. She has denied any connection to the holding company at the centre of the case - Exem - which she says was owned by her late husband, rejects charges of wrongdoing and says she faces a political witch hunt by Angola’s new leadership. Representatives of Exem did not reply to a request for comment. Dutch law firm Van Doorne, which represents Exem in the lawsuit, also did not respond to a request for comment. The legal claim by Sonangol is due to be heard in the last week of May in the Amsterdam court of appeal, the 100%-state owned company’s lawyer Emmanuel Gaillard of law firm Shearman & Sterling said. It will argue that Exem’s stake was acquired through embezzlement and money laundering.

“It’s all corruption ... you (Exem) owe us the shares, the indirect participation in Galp, because it’s theft. It’s illegal, therefore you have to pay it back,” Gaillard said. Sonangol’s lawyers say the sale by Sonangol of part of its stake in Esperaza to Exem made no business sense for Angola and was made to enrich the former first family. Under President Dos Santos, Sonangol sold a 40% stake in an offshore holding company, Esperaza, to another holding company -Exem - owned by Isabel’s husband Sindika Dokolo, a Congolese businessman who died in a diving accident last year. Esperaza, in which Sonangol retained a 60% stake, in turn partnered with the business empire of Portugal’s Amorim family to form yet another holding company, Amorim Energia, which is the largest shareholder in Portuguese oil company Galp Energia with a 33.3% stake. The value of holding company Exem’s indirect stake in Galp fluctuates with oil prices and is currently worth about $500 million. A source with knowledge of the Amorim family’s position, who declined to be named, said its main interlocutor in the joint stake was not Exem but Sonangol, calling their partnership with the state firm “good and close”. “(The case) does not affect these relations, it does not change anything,” the source added. Galp has said it has no dealings with Dos Santos. It declined further comment for this story. The dispute, which is being heard in Amsterdam after both sides agreed on arbitration, already resulted in a ruling last September that removed Exem’s representative from Esperaza’s board and put its stake under the control of a court-appointed trustee. Camilo Schutte, the Amsterdam lawyer selected by the court to represent Esperaza, said he was not currently party to the litigation and referred questions to representatives of Sonangol and Exem. By Noah Browning with additional report by Sergio Goncalves, Barbara Lewis and Jan Harvey