4 minute read

Joe’s journey to mayor

LOCAL COUNCILLORS and MPs of Caribbean heritage played a hugely important role in tackling racial discrimination in the post-Windrush years.

The Windrush generation first became involved in local politics in the decade after arriving, but it took until the 1970s for the first wave to get elected to their council’s town hall chambers.

Local government pioneers like Randy Beresford, who was elected in 1975 in Hammersmith and Fulham, went on to become one of the first Black mayors in the country to wear the ceremonial chain. Ben Bousquet in North Kensington was another who made it.

But it was the 1980s that marked a sea change in the way political parties respond to voters of Caribbean and African heritage.

The inner city riots which marked the start of the decade were a wake-up call to a Britain which had largely ignored a marginalised and over-policed Black community.

Powerful

The activism of the Black Power movement which came to prominence in the Mangrove Nine trial laid the foundations for a powerful network of Black and minority ethnic councillors and council leaders who pushed for the major political parties.

This period saw the likes of Guyana-born Bernie Grant — later to become a legendary MP — elected as leader of Haringey Council in 1985.

The same year Linda Bellos, of Nigerian and Polish-Jewish heritage, took the reins at Lambeth town hall. Other notable councillors included Russell Profitt, Martha Osamor, and Lurline Champagnie who represented the Conservatives in Harrow.

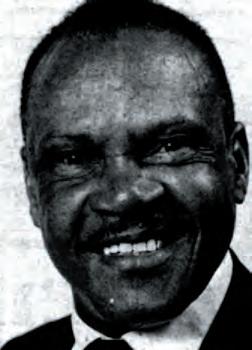

Among this cohort was Joe Abrams, a councillor who represented the Graveney ward in Mitcham for over 20 years after being elected in 1982 before go- ing on to become the borough’s first Black Mayor.

His career in local politics and public service left a legacy that inspired his son Kingsley, who forged his own career in politics, also becoming a Merton councillor four years after his father’s election.

Impressive for a Guyanese immigrant who arrived in Britain in December 1960 with three pounds in his pocket.

However, like many members of the Windrush generation who arrived in the 1960s, life in the ‘Mother Country’ was not easy.

“Life in Britain was difficult and hard for my parents,” says Kingsley.

“After my mother arrived they found a place to live but it was with a lot of other people all living in one room. My father was trying to study, work and raise a family. I was born in 1962, so I joined them in this one room.

“They later got a place of their own. But life was so tough my mother decided to return to Guyana in 1964. She was pregnant with my sister at the time and took me back to stay with my grandmother. So we grew up there until I returned to the UK in 1977.”

Abrams came to Britain with the intention of furthering his education and a burgeoning career as a teacher. In Guyana he had also been politically active as a member of the country’s People’s National Congress (PNC).

The future mayor found work as a bus conductor with London Transport so he could support himself while studying, and went on to become deputy head at Bow Boys school in Tower Hamlets, east London.

Abrams gained a reputation as someone who was forthright about the issues affecting Black residents of Merton after he joined the Labour party in the late 1970s and became chair of the National Association of Community Relations Councils.

When, in 1982, Abrams decided to stand as a Labour candidate in Mitcham’s Graveney ward, many activists didn’t rate his chance of success.

“The ward was held by the Tories and had been for many years despite it having a large Black population,” Kingsley recalled. “So when he was selected to stand in the election not many people thought he would win because Graveney wasn’t seen as a safe Labour seat.”

Proud

Abrams felt that if he could get his ideas across to the ward’s Black voters they would back him at the polling booth. And his intuition proved correct after he won the seat against all expectations.

Following Labour’s successful local election campaign in 1990 which saw the party take control of Merton Council, Abrams was made mayor of the borough in 1991.

Rough

BEGINNINGS: Left, the house that Joe Abrams was born in at Beterverwagting, East Coast Demerara, Guyana; right, Randy Beresford was elected in Hammersmith and Fulham; far right, Lurline Champagnie represented the Conservatives in Harrow

“It was a proud moment for him, for our family and for the local community,” says Kingsley.

“Here is a guy who was born in Guyana in this rackety old house, he came to England with three pounds in his pocket, roughed it out living in one room with his family then went on to become deputy head of a school, then a local councillor and then the first Black mayor of Merton.

“And my mother, who came to this country at the age of 18, was now Mayoress, which was a dream for her.

“There were many people in the borough who were part of the Windrush generation and settled in the borough in the 1960s. They had struggled, they had faced racism and in the face of it went through school and worked hard to buy their homes. And now they had a Black mayor of Merton. It was an amazing achievement and you could see it on their faces.”

When Abrams died in February 2012 tributes were paid to his selfless dedication to the people of the borough and his efforts to achieve racial equality.

Speaking about his father’s impact on his own career, Kingsley says: “One of the greatest legacies he left was to show me that Black candidates who stood in elections could win if they got organised and had unity.

“When he was in Guyana he was active in the People’s National Congress. He played a big role in the party’s campaign strategy focusing on getting the support of key groups of voters.

“He was a big influence in the work I did with the Labour’s Black Sections, an organisation that was pivotal to getting Black MPs elected in October 1987.”