4 minute read

p3, 4, 6, 8

Mental health

Mental health experts demand to be heard as the government overhauls the law. By Vic Motune

AS THE government introduces plans to tackle racial disparities in mental health ‘sectioning’, race equality campaigners say black communities must be heard.

Black people are more than 10 times more likely to be subject to a community treatment order, and more than four times more likely to be detained under the Mental Health Act, according to recent data from NHS England.

The latest Queen’s Speech included a promise to bring in a draft bill to address racial disparities in the use of compulsory powers, with a parliamentary committee set up to advise on new legislation.

However, mental health organisations say they should be given an input into how the law is reformed, in an effort to make it fairer for people from minority communities.

The Voice spoke to Ariel Breaux, strategic delivery manager for race equity at Mind, about the key factors to reduce racial disparities.

Ariel Breaux: One of the key things to focus on is how racism manifests and is reinforced through the use of the Act.

It’s very important that the parliamentary committee doesn’t neglect that the mental health system is institutionally and systemically racist.

It’s only from this starting point that they can critically examine how the Act goes on to contribute to such inequitable treatment of black people, and how the inequitable use of the Act can be linked to racist ideology, like beliefs of dangerousness, that sees black people more likely to be placed under various types of state sanctioned control.

A prime example of this can be seen with Community Treatment Orders, which are a point in the Act where racism meets perception of risk, power and coercion.

The Voice: Some say that what would help to create a better understanding of race inequality in healthcare is the involvement of more black people in patient and public boards within the NHS, Local Health and Wellbeing Boards, Clinical Commissioning Groups. Do you think this is important?

AB: This is incredibly important. There’s a saying that goes, ‘no decision about us without us’. You cannot address the issues that face people of colour without considering our voices and experiences. Redistributing power is central to dismantling the systems that perpetuate these inequities.

Additionally, we need to be led by people with mental health problems, making sure their voices are heard and acted upon.

Involvement should not be transactional, rather, it must be understood that creating a better understanding of race inequality in healthcare cannot be done without those who experience it leading the way. TV: Campaigners say that this understanding must reflect itself in the whole of the care pathway, from prevention, to assessment, to therapeutic intervention to sustained recovery. What would a whole care pathway that takes into account race equality look like?

AB: From start to finish we need to be looking at the ways in which systemic and institutional racism manifests within health and care. For example, we know that many black people seek help for their mental health issues and are turned away, then don’t get help until they are much more unwell. So we need to be critical in our assessment of the current care pathway asking questions like ‘how are we relying on assessment practices and therapeutic interventions that were created without people of colour in mind and are not culturally appropriate? How does our view of sustained recovery ignore the nuances about what recovery means for people of colour?’

When thinking about prevention, are we considering how interpersonal, institutional, and systemic racism within the larger society underpin the poor mental health of people of colour?’

We have to look deeper into root causes and contributing factors to avoid solutions that don’t truly address the problem. health legislation and service provision include things such as provide better access to talking therapies and culturally relevant interventions?

AB: Overall, there needs to be better access to culturally appropriate interventions, and at an earlier stage, rather than taking a one size fits all approach.

Culturally appropriate therapies are a must, but not all services are culturally appropriate despite being labelled “evidence-based” and providing more access to therapies that are not fit for purpose won’t solve anything either.

Services should be codesigned and co-produced with those from the communities the services will be targeting.

TV: Campaigners are also pushing for legislative reform to acknowledge the way wider determinants such as poor housing, insecure employment and living in areas where GP practices are more likely to be poorly rated can exacerbate mental health inequalities.

AB: I completely agree with this. We cannot treat mental health issues in isolation as if other environmental factors do not have an impact on mental wellbeing.

It is imperative we take an approach that centres social justice, and seeks to intervene at all levels.

We need to make sure there’s multiple levels of intervention and avoid locating a problem in the individual when the problem actually resides in the social system.

Neglecting to do so can result in inaccuracies in treatment and diagnosis, as well as causing harm.

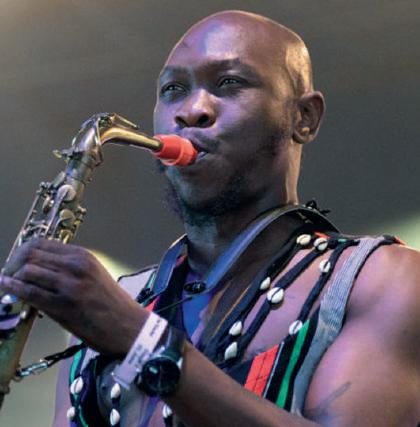

FEELING ISOLATED:

Having mental health issues as a black person can be tough, as they can fear the impact of institutional racism (photo: Getty Images. Posed by model); inset below, Ariel Breaux

Lifestyle

New sound, familiar name: Seun Kuti p56

BLACK UNITY BIKE RIDE 2022

Ready to ride out p52

No joke: Eddie Kadi is gonna

show em Ghanap57