10 minute read

Oyster Wars circa 1880

by Louis C. Wainwright

Transcribed, edited and with notes by James Dawson from an old manuscript he found

There are many places where oysters may be taken. I have seen them in southern waters and even attached to the branches of a tree, but so far as I know the great oyster industry centers in Chesapeake Bay and its many tributaries.

Now oysters are planted in the wide bay at the mouths of the tidewater streams, and it is there that the tonging industry flourishes.

Chesapeake oysters are also superior and have few if any real rivals.

The great rivers of Maryland and Virginia have such an extensive range of oyster grounds that many people follow tonging throughout the winter. So great is the draught upon the oyster grounds in both bay and rivers that more and more the state needs to enact legislative protection.

To what degree Maryland derives income from licensing oyster boats at the present time [1941] I cannot say, but fifty years ago a very large part of the public school funds depended upon the revenue derived from the oyster industry.

Perhaps, also, there was less widely spread information concerning oysters, which was sometimes manifested to a surprising degree.

Having gone to the 1892–3 World’s Fair in Chicago, I thought I would visit the Maryland exhibit, wondering what particular features would mark the produce of such a diversified state whose lands range from sea level to mountain tops, whose shoreline offers an embroidery pattern, whose peaches, berries, and melons, not to mention corn and hay, have scarcely superiors, and whose bay is unsurpassed, whether for pleasure or produce. The building was not pretentious, and its major exhibit was large and humble, with nothing scenic about it; but there was nothing insignificant. Coal, asbestos, fruits, cereals, melons, all showed to advantage.

A golden Knabe piano manufactured in Baltimore was conspicuous. On a visit to the White House, I saw a golden Knabe (as I remember) and wondered if it was the one I saw at the World’s Fair. But not to digress, I may say the prominent feature of Maryland’s exhibit was an oyster

Oyster Wars

packing house reaching out over an extended waterway and having a pile of oyster shells beneath the shuckers’ bench, and crawling and swimming about were diamondback terrapins, which were not then almost extinct.

Two well-groomed ladies were watching the terrapin as they swam among or about the shells. Said one: “What are they, those things? Replied the other: “They must be oysters.” Said the former: “Which?” Replied her companion: “I am not sure.” So much for inland America! But Maryland was reaching out with her advertisement. Booth and others were sending oysters far and near, and a few years later I could purchase raw oysters in the newly settled parts of Wyoming, hermetically sealed and packed on ice. The fame and consumption of oysters has greatly increased. It has been necessary for fifty years or more, to police the oyster grounds. Even at the early date I mentioned, when the police fleet consisted of sloops or schooners, there were many depredations of the tonging grounds and many other violations of the oyster laws.

Despite the best vigilance of the oyster police, unlawful dredging

Oyster Wars

was constantly carried on in one region or another, and sometimes a collision between the officers of the law and some daring crew engendering retaliation enlisted a number of dredgers to combat execution of the law. On several occasions, the dredgers banded in considerable numbers and an oyster war was on, and that in no paltry proportions. It was not always easy for the authorities, for first there was the need for a number of boats and sailors sufficient to guard a very long Bay and which to guard properly would require a much larger navy than the state could easily afford; a second

Oyster Wars difficulty was that the dredgers offending were much more daring than the officers, and more numerous. They lacked authority, which was a great handicap. They acted illegally.

The officers were, likely, by political appointment and were not necessarily brave or able seamen. Perhaps there were nine or ten police boats and crews, perhaps there were a hundred or more fine captains with good crews and fine boats.

To this add that the young bay captains were good marksmen. Captain Jimmy of the oyster po - lice knew these things, and that explains his sudden leap down the companionway where he ran across a recalcitrant dredger with his rifle in hand.

In the 1880s, the oyster wars in essence did not differ from individual clashes with the oyster police, except in numbers and possible prolongations of the effort to dredge unlawfully or the pursuit of the law breakers, therefore I shall illustrate what occasioned hostility between the dredgers and the officers of the law. To do this we will look down Tangier way until you come to Cale Preston (Caleb Preston) and his wife Sarah.

Cale was a lithe, likely young

Oyster Wars

fellow about five feet eleven inches tall, generally genial and very determined. Sarah was a kindly, placid young woman conforming by nature and rearing to the traditions down Tangier way.

She was neither nervous, hysterical, nor excitable, but homespun and loyal, and for this reason easily responsive to Cale’s ideas and with him looked admiringly upon his trim schooner and longingly on the river oyster beds.

In spring Cale had the garden plowed and harrowed and put in the potatoes and cleared out the strawberry patch. It was his year’s contribution to the house work.

After that he left matters in the hands of Sarah, who without complaint conformed to wifehood down Tangier way.

Cale painted his schooner, repaired all the blocks and tackle and whitened his sails.

If he felt “spry” and vigorous, he might take Sarah for a run to Baltimore, keeping an open eye to the condition of the oysters in the broad-mouthed rivers and mentally locating the beds which he might at times visit in the fall, one moon-lit night.

As for Sarah, whatever Cale did was right, and it was a dirty trick for the police sloop captains to pursue him “for a few old oysters.”

The several police vessels from Baltimore to Little River knew Cale’s prowess. He was a likable young fellow and as handsome in his movements as a movie star., and they liked him. He was prone to dredge the tonging grounds, as they watched him; he was an unnerving rifle shot, wherefore they treated him with due regard on the old Bay; and he was daringly alert and ready. He had the nerve and in a war of nerves the police captains often had the jitters.

Moreover, Cale’s schooner was obedient to the helm and he knew the channels and never risked any depredation until he had learned the river’s channels. And he was alert.

If several captains thought to block his way or hem him in, Cale merely dredged the bay, and as he passed and repassed he located the police sloops gathered about him. If one was tracking him he lured them out of the channel and with a rush swept by them. If they blocked him, they learned that Cale knew powerful and alarming tricks. They just could not catch him in unlawful dredging, though they knew he was a leading man of the (oyster) wars.

Power vessels for police patrol had not been introduced, and not a sloop or schooner of the oyster navy (if so the police squadron may be called) had Cale’s equal at the helm.

One night he said to Sarah: “Honey, I’ve been looking ’round. The Bay oysters are not very fat but up toward Potomac or Big Wicomico I think I could load up without much cost, so do not be surprised if I do not return for a week.”

Sarah was not surprised, but reaching over she offered him the sausage and said, “Cale, honey, yo’ll be keerful won’t cher?” It was on this trip that Cale accidentally fell into an engagement with the oyster navy. Others had conceived a similar plan, so that into whatever water Cale turned he found others were there.

Now, Cale’s strategy was not to be hampered by other boats and their maneuvers. He sensed signs of the police patrol and consequently swung out to the bay, pondering the while whether he should try the Nanticoke or slip up the Potomac, where he knew the battle was on and would be over before he could reach the tonging grounds. The moon was at half good light, but not too much. He determined on Potomac and found, as he expected, that the battle was over and the boats dispersed. One police boat seemed to be left to guard against any later encroachments. Cale determined on a strategic move that was precarious, but that seemed necessary, unless he would abandon his night’s poaching. He thought to entice the patrol into other waters, and to do this he sought to awaken suspicion by hovering near the river’s mouth and tacking near the police boat. His scheme proved fruitful. The patrol followed him as he led them to other tonging grounds, whose channel and beds he knew better that the police captains did.

He entered on the grounds and simulated dredging, always keeping the channel easily accessible. Cale recognized the police boat and knew the vulnerable quality of its captain,

Oyster Wars

but he purposely kept his boat in dim light so that he himself should not be recognized.

Now Cale, as said, was an accurate marksman. Perhaps he was no competitor with “Natty Bumpo,” “Billy the Kid” or of “Buffalo Bill,” but it is problematical whether a mere nearly accurate marksman plied the Chesapeake; and had the patrol on watch known he was stalking Cale’s schooner, I doubt that he would have continued on guard in those waters.

As it was, he followed Cale and was tempted in his efforts to overhaul him and force him inward and at some distance from the channel.

This was Cale’s grand opportunity. Skillfully running in easy range of the state’s patrol and giving the helm into the mate’s hand, Cale, with rifle in hand, and giving directions now and again about the maneuvers, watched until he could locate (or nearly so) the ropes and pulleys. Unsuspectingly, the police boat turned to intercept Cale’s schooner, when his rifle rang out, cutting through the sail and weakening a rope. It was Captain Jimmy’s police boat, and just as

Cale anticipated, Captain Jimmy hurried “below.”

Captain Jimmy’s crew did not feel more ambitious to be penetrated with bullets than did their redoubtable captain, so that the pursuit weakened.

It required some little time for Cale again to maneuver into favorable position, which emboldened Captain Jimmy to ascend the companion way and to shout orders like a brave man.

He stood at the door of the companion way much as a prairie dog stands at the mouth of his hole and barks or cheeps, but ready to drop at the slightest occasion, back into his burrow.

Captain Jimmy’s crew were armed, but it did not occur to them to use arms, rather to use their legs.

Cale, meanwhile, had his rifle poised, and whether by accident in the dim light or by skill, he achieved the remarkable, his bullet severing the main sheet and dropping the huge sail as a sudden blanket of snow over the men and deck.

It was enough. The enemy had been successfully engaged and were helplessly adrift on the tide, and that for a long time.

Regimentals and a salary by political appointment are fine, but can in no way compensate for a clever mind and nautical skill.

There was a great sputter and splutter in officialdom, and none were certain whether another rifle

Oyster Wars

ball might not again tear through the rigging.

Captain Jimmy, bold warrior, was afraid to come up the companionway; the men were in vocal doubt concerning the sharpshooter’s next move. During their confusion, Cale, almost running before the wind swept down the channel into the bay, and his men shouted as they passed, “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again, Captain Jimmy!” Thus was ended the last skirmish of that day’s battle in the oyster war.

Leaving the police boat, Cale dredged another river and filled his boat.

Afterword by J.D.: This is a chapter from an old manuscript I found titled “Down Tangier Way,” in which Louis Wainwright wrote about his life on Deal Island in Somerset County, Maryland, in the early 1880s.

Although the incidents in this story seem real enough, I have not been able to verify the name Caleb Preston, so I suspect that the name was fictionalized. Whoever he was, he had been involved in various illegal oystering activities, so Wainwright had good reason to protect his identity—even writing about him 50 years later, as he may have been alive and still poaching. Locals certainly would have known who “Caleb Preston” really was.

Likewise, Capt. Jimmy. Notice that Wainwright did not give Capt. Jimmy a last name, so there may well have really been a Capt. Jimmy.

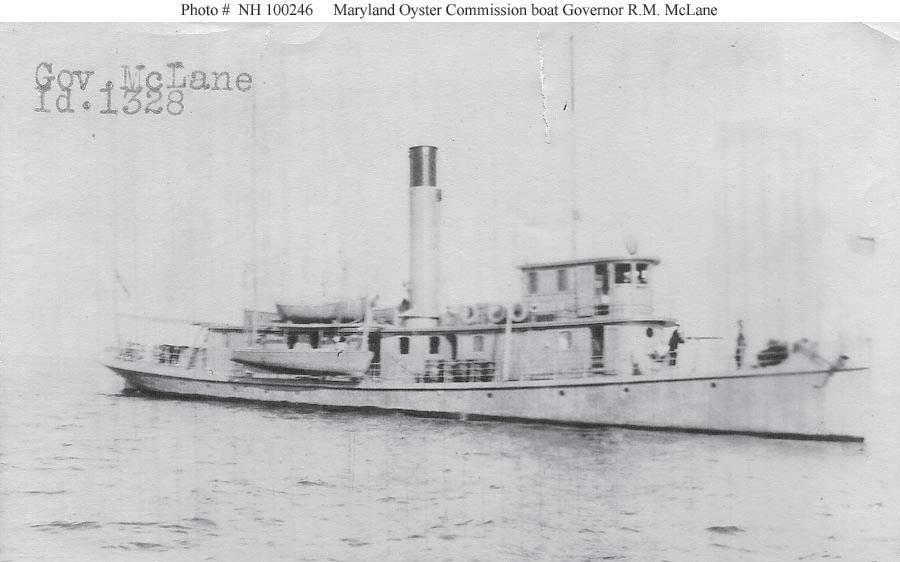

In fact, in the 1890s, Capt. James A. Turner of Wicomico County was commander of the police steamer Governor R.M. McLane, but that could have just been a confusion of Capt. Jimmys.

The Governor R.M. McLane was real enough and the flagship of the Maryland State Oyster Police Force, a.k.a the “oyster navy,” which had been established in 1868. Armed with a 12-pound howitzer on deck plus plenty of rifles for her crew, she and her companion steamer Governor Thomas went into service in the fall of 1884. But, as Wainwright noted, the oyster navy was not yet using powered vessels against “Cale” then, so Capt. Jimmy, whoever he was, was on an earlier, sail-powered oyster police boat.

When “Cale” whitened his sails, that meant he laid them out on shore and bleached them to make them snowy white. The canvas sails used then would easily stain and become dirty. Beaching the sails would not have made a boat sail any faster, but it sure would look sharp sailing in its Sunday best.

For more on the oyster wars, see John Wennersten’s The Oyster Wars of Chesapeake Bay, Tidewater Publishers, 1981.