3 minute read

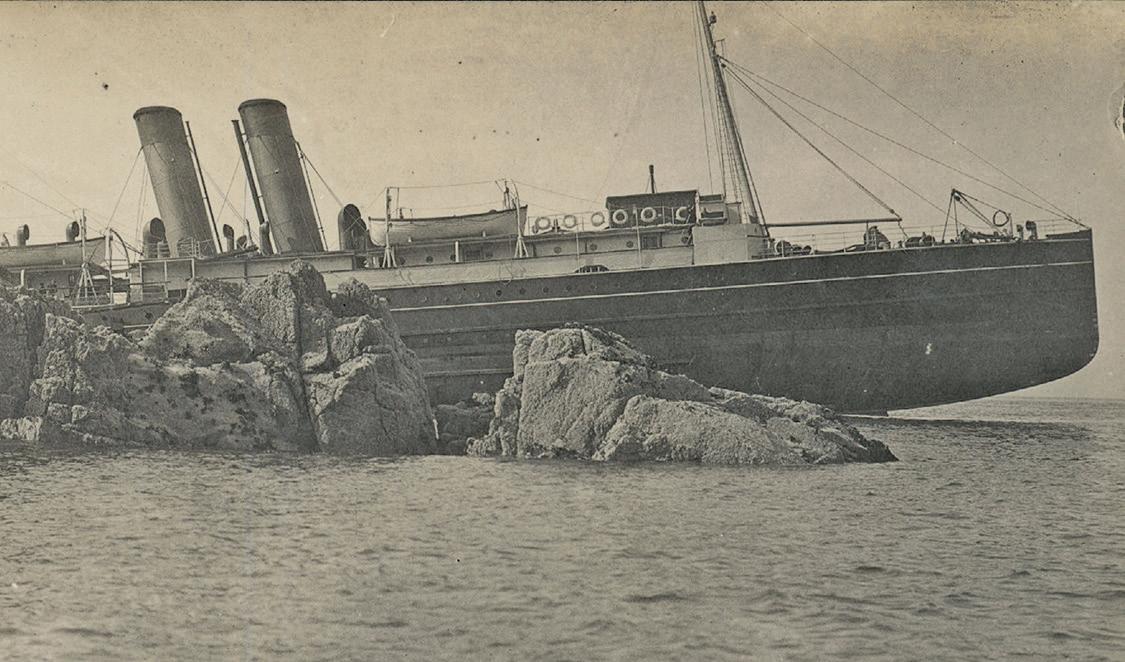

Shipwrecks and Rescues

tic west of Ireland’s coast. In his memoir Twenty-Years A-Growing, O’Sullivan described the relief of the rescued captain.

Bound from New York to Liverpool in 1916, the Quebra ’s captain had changed course after a German U-boat was sighted. Around 3 a.m., Quebra grazed one rock, then struck another directly and began to sink. The captain launched his crew into two lifeboats and then took a third boat himself, along with his mate and the lone-remaining crewman. At daybreak, isolated Great Blasket Island came into view. The three men searched along cliffs for a possible landing.

202 Morris St., Oxford

410-226-0010

Booksellers

off your book clubs’ books *Books of all kinds & Gifts for Book Lovers

*Listen Fri. mornings on WCEI 96.7fm

“We thought then that it was some backward country with no one alive in it,” the captain related. “There was a great, sweeping swell on the rocks.”

Likely he and his companions were leery of the reception they might encounter if the strange island were populated. Searching half an hour for a safe landing, they had ample time to mull over old tales of “wreckers” who historically threatened survivors in the region. Some such villains even made a living by tricking ships onto a beach. The Quebra had set out from New York, where old tales recalled Long Island wreckers. Farther south, the name Nag’s Head was said to derive from wreckers on the Outer Banks who hung a lantern from a pony’s neck. As the pony was led along the shore at night, the swaying lantern suggested a ship sailing to shore ahead of the intended victim, who would be lulled into false security and run aground.

This well-recorded trick had reputedly crossed the Atlantic from England, not far from the Quebra survivors’ location. Formerly, salvaging a wreck’s cargo was legal only if all aboard were dead. Along with cargo and wreckage, looting the quick and the dead was said to have been common. As they rowed around the forbidding cliffs, the Atlantic pounding ceaselessly against the rocks, they must have felt akin to historic seamen in peril from more than the sea.

Meanwhile, Blasket fishermen, who eked a living from the surrounding waters, watched from atop the cliffs. They saw the sink- ing cargo ship and watched the first two lifeboats head off toward Dunquin harbor on the Irish coast. Knowing where the captain’s circling lifeboat would find a safe island landing, they descended to the strand to wait.

When the seamen were safely ashore, locals assisted the injured crewman up to their village for attention. The captain told the assembled group of the nighttime foundering and how they sighted the island and groped for a landing, wondering if the island were inhabited. O’Sullivan quotes the captain, relieved at the kindness of the fishermen awaiting him: “Upon my word, you are here ~ fine, well-favoured people, man - nerly, intelligent, generous, and hospitable.”

The village leader said, “I promise you, since the war began, it is many a sailor has been saved here from the sea. And as for attending them well, they get what we have. But you must be cold and wet standing there. Come up into the village.”

For months afterwards, every north wind brought riches to be salvaged from the tide. As O’Sullivan said, “From that out there was plenty and abundance in the Island ~ food of all sorts, clothes from head to heel, every man, woman, and child with a watch in their pockets; not a penny leaving home; everything a mouth could ask for coming in with the tide from day to day ~ all except the sugar which melted as soon as it touched water.”

(Being a youngster at the time, he lamented this loss.)

A bedtime prayer among the impoverished children of England’s coast was, “God bless father and mother and send a ship t’shore ’fore morning.”

Back on our side of the Atlantic, no known evidence indicates that ruthless wreckers ever prowled Delmarva’s coast. In 1903, Scribner’s Monthly interviewed the Hog Island, Virginia, lighthouse keeper. Of fishermen living amid those shifting sands, the keeper said, “It’s never been charged against the natives of Hog Island that they ever lured vessels to their destruction by false lights and signals, as did the wreckers of Nag’s Head, nor did they decoy them in the shallows like the natives of Roanoke Island.”

Above Delmarva, a New Jersey islander defending his reputation testifying in the 1800s, “Them stories is injust. The men as is called Barnegat pirates are not us fishermen…never were. They’re from the mainland and such…as come down to a wreck…. We do our share of stealing, I’ll confess, but from Sandy Hook to Cape May, it’s innocent to what’s done on Long Island. No man or woman was ever robbed on this beach till they was dead. Of course, I don’t mean their trunks and such, but not the body. The Long Islanders cut off fingers of living people for rings, but the Barnegat men never