9 minute read

Easton's Potter's Field: James Dawson

Easton’s Potter’s Field by James Dawson

One historic site of Talbot County that I’ll bet you’ve never heard of is Easton’s Potter’s Field, as it is doubtful that a cemetery for paupers and criminals would ever make it onto lists of Things To See And Do in Historic Talbot County. Nevertheless, the Good Old Days weren’t always so good, and many places had a Potter’s Field, even Colonial Williamsburg.

But first, why is a cemetery for paupers called a Potter’s Field? The first use of the term Potter’s Field is in William Tyndale’s 1526 translation of the Bible for Matthew 27:5 of a “potter’s field to bury strangers in,” but that actually meant a field owned by a potter. Or someone named Potter. Or maybe even a potter named Potter. A Potter who was a potter. However, by the 1700s, it came to mean any field used for the burial of paupers, as potters were often thought to be poor.

On Feb. 28, 1843, the General Assembly of Maryland passed a bill authorizing the commissioners of

the town of Easton to accept from the heirs of John Goldsborough, deceased, a deed for the sale of a lot of ground for “the use and purpose of a common burying-ground or Potter’s field…”

I had found scattered references to Easton’s Potter’s Field over the years, but no precise location other than that it was somewhere on Glebe Road.

Talbot County, like every county in the state, not only had their own Potter’s Fields for the burial of paupers and criminals, but a gallows for the hangings of the criminals, too. This was not the so-called hanging tree on Miles River Road, but a real gallows that could be a whole other story in itself. It wasn’t a permanent gallows, but only erected when needed. In 1875, it was near Frank G. Wrights’s race course on Point Road.

Sadly, the hangings of convicted criminals were public events then, and, however barbarous that seems to us now, were perfectly normal then. The hanged criminals were often buried in Potter’s Field.

When Frederick Lawrence, a black man, was tried and convicted for the murder of his wife on Oct. 2, 1870 and sentenced to death, his hanging was witnessed by an estimated 5,000 people. It was an interracial event. “Whites and blacks freely mingled and commingled,” as

BAILEY MARINE CONSTRUCTION, INC. A 5th Generation Company - Since 1885 COMPLETE MARINE CONSTRUCTION

RIPRAP · MARSH CREATIONS BAILEY DOCKS · BOAT LIFTS Heavy Duty and Shallow Water STONE REVETMENTS

MD H.I.C. Lic. #343

410-822-2205 Call for a free estimate! baileymarineconstruction.com

the paper put it.

The execution was a big deal because it was Talbot’s first hanging since 1837 and merited a long, detailed article in the Easton Star Democrat. Sheriff Bennett had even taken the precaution of closing the bars and liquor stores to prevent a breach of the peace. Consequently, no one was drunk, and perfect decorum prevailed through the day.

After Lawrence declared his innocence and blamed the cause of the murder on a former friend, he forgave everyone and bade them farewell. The trap was sprung and the body was taken down, placed in a coffin precisely at 12 noon and taken away by his friends for burial.

The day before, Lawrence “had sent for Wm. Lewis (col’d), and requested him to dig his grave and bury him in Potter’s Field; to plant a cedar post at each end of his grave; and to plant a willow tree on his grave, so that the people who should visit it hereafter might say, ‘here is the grave of Frederick Lawrence, the murderer, and be warned against the commission of crime’” [Easton Star Democrat July 18, 1871].

Potter’s Field was used for some years. It is probable that most of the graves were either unmarked, marked with field stones or only had wooden markers that have long since rotted away.

By 1916, the Town had purchased a lot in Spring Hill Cemetery for the “burial of strangers” and no longer used Potter’s Field, which had grown up in briars and bushes and had become unsightly and a nuisance to the surrounding neighborhood. On March 3, the Maryland Legislature granted Easton permission to sell Potter’s Field, provided “the said Town to make proper provision for the removal of any bodies buried therein to some better and more suitable location.”

But, if they tried to sell it, no one wanted to buy it. However, the public kept using it sometimes, and one might expect that it saw some burials during the Spanish Influenza epidemic of 1918 to 1920, which killed hundreds in Talbot County.

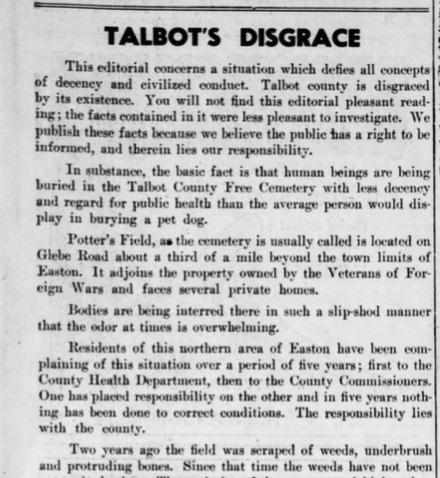

By the 1940s, the condition of Potter’s Field had deteriorated badly. An eloquent editorial titled “Talbot’s Disgrace” in the Aug. 5, 1949

Easton Star Democrat detailed the unpleasant conditions there:

“…when human beings were buried in the Talbot County Free Cemetery with less decency and regard for public health than someone would display burying a pet dog…

“Bodies were being interred there in such a slipshod manner that the odor at times is overwhelming.

“Residents of this northern area of Easton have been complaining of this situation over a period of five years; first to the County Health Department then to the County Commissioners. One has placed responsibility on the other and in five years nothing has been done to correct conditions. The responsibility lies with the county.

“Two years ago the field was scraped of weeds, underbrush and protruding bones. Since that time the weeds have not been cut a single time. The majority of them now stand higher than a man’s head.

“This past winter the body of an infant was buried by a couple and no one knows who or why but the couple was seen by residents with the tiny bundle digging in the field…

“The bodies of other children have been ‘buried’ by digging a shallow trough and piling dirt on top.

“Nobody knows how many people are buried in Potter’s Field, or where they are buried because no records are kept and there is no plat of the land.

“Coffins have been buried practi-

cally level with the ground and dirt piled on top. Five years ago a nearby resident found his son poking a stick under the lid of an exposed coffin to look inside… “A situation which developed last week was perhaps the worst to date.

“On Friday morning a narrow path was cut through the weeds and the body of a man was buried some 25 feet back from the road. The grave was so shallow and the temperature so high that residents soon complained to the County Health Department and to the Sheriff. On Saturday, the body was removed and for no valid reason was left standing beside the open grave in the hot sun for more than three hours. It was finally reburied Saturday evening. By Sunday morning the odor became apparent again and upon examination it was found that the second burial had placed the box even with the ground. At no point did more than five inches of dirt cover the so-called ‘coffin,’ the marking ‘this end up-No hooks’ upon the end of which, and its plywood construction gave rise to the speculation that it formerly contained either a refrigerator or a radio.

“We are among those who believe that in America the worth and dignity of the human person is not measured by his bank account but rather by his membership in the human race. Most of the occupants

of Potter’s Field have been useful citizens in their lifetime and as such contributed their share to the common good. It was their misfortune to die penniless, without family. We cannot concede that the worst human being alive is not entitled to a decent, civilized burial. We believe the people of Talbot county will agree” [Easton Star Democrat Aug. 5, 1949].

The paper also said that Raymond Wood and about a dozen other Glebe Road residents met with the county commissioners to complain about the condition of the place. Dr. Louis Welty, county health officer, suggested that it should be moved to some other location, apparently unaware that the town and county has stopped using it years ago.

Somebody must have pulled some strings, because in December a law was passed by the State Legislature requiring counties to deliver bodies to the morgue in Baltimore. After embalming and a 48-hour waiting period, they would be turned over to the State Anatomy Board for eventual distribution to medical centers in the state. In practice, however, they were held for about three years in case someone came to claim them.

And so, finally, that was the end of Potter’s Field.

But not quite.

By now, no one was sure who owned it, and there was an ongoing dispute between Easton and Talbot County about which one owned it, apparently because of the nuisance of having to do the maintenance on the now obsolete cemetery. Neither wanted it, and each was hoping that it belonged to the other side. To further complicate things, it

wasn’t even in the town limits then and had certainly been used by the county.

The situation was finally resolved in 1958 when Town Attorney Clark Ewing found the deed. And, as Ewing pointed out, there was no reverter clause in the deed that the land would return to the original owners if it was no longer used for

Charts go with any décor

Chart Your Way to the BEST CUSTOM FRAMING!

410-310-5070 125 Kemp Lane, Easton Plenty of Off-Street Parking

Call For Availability

that purpose, so no luck for the town there.

But where, exactly, was Potter’s Field? Using clues in old newspaper articles and some historical sleuthing, I finally located it as a 2.8-acre narrow strip of land about 100 feet wide on Glebe Road running behind and parallel to the Easton Plaza Shopping Center, next to the V.F.W. property. And, much to my surprise, it had not been paved over or built on. The sign on a nearby dumpster warned “NO PUBLIC DUMPING $500 FINE,” so I did not expect to see any protruding bones or exposed coffins. Too bad that sign wasn’t there 70 years ago.

It is nicely maintained now by the Town of Easton, and the trees on it give it the appearance of a little park. Nothing is to be seen of Lawrence’s willow tree or cedar posts. Or anything else. In fact, when I visited it recently, two women from the Amish Country Farmer’s Market were sitting at a picnic table there enjoying the day, completely unaware of what might lie beneath.

Addendum: I just happened to look at the 7th edition of the ADC map of Talbot County to see it on the map and in the index as Pooter’s Field [sic]. Such is fame.

James Dawson is the owner of Unicorn Bookshop in Trappe.