12 minute read

COVER

FEATURE ka’axtawaq h North Wind Place

A walking tour at Foster Park

by Kimberly Rivers

kimberly@vcreporter.com

ts̓ap ši’išaw | House of the Sun | Red Mountain looking west as the sun descends.

Etymology may seek to find the original history of a word. But as living descendents of local indigenous tribes reintegrate, mitsquanaqań (Ventureno Chumash), the language of their ancestors into their daily lives, the rest of us have an opportunity to learn the names first given by the first people of this place where we all live today.

“At 26, I set out to see if our language could be revitalized. Our last speakers had passed away in the 60’s, however I learned of the voluminous notes of the ethnolinguist, John Peabody Harrington,” said Matthew Vestuto, a member of Barbareño/Ventureño Band of Mission Indians. He has served as language program coordinator for the tribe. He graduated from Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, with a degree in Language Revitalization, Linguistics and Media and is a Board member of Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival. “There is ample ‘deep sentence structure’ recorded which assures we can revitalize [our language]. There’s some audio, too. In the course of transcribing these notes, I saw placename trips here and there, so I began to collect these in one place. Then I mapped them with some help from my friend Devlin Gandy.”

Those maps, and other stories Vestuto is gathering and learning are being coalesced into a publishing project through ’iskiliwil, the publishing arm of the mitsqanaqań language revitalization effort. “I’m reorienting to our indigenous worldview. People talk about culture, but neglect the culture dish, the context. Knowing our world, in our language, is foundational,” he said in explaining the importance of this work to him. “Placenames are a wonderful way for our people to begin learning our language. It doesn’t involve complicated grammar and the names are immediately applicable.”

Last week, the Ventura County Reporter joined Vestuto for a walking tour at Foster Park along the Ventura River to hear some of these stories and place names.

“Our ancestors were hospitable and welcoming. Stealing land tends to sour that cultural value, however, I feel that sharing our intimate understanding, and love, of place will enrich the residents and visitors to our territory, inspiring in them a love and a deeper sense of responsibility for the health of our world.”

ts̓ap ši’išaw | House of the Sun

“This is Red Mountain. In our language it’s called ts̓ap ši’išaw, House of the Sun.” Vestuto said. “If you stay around here

around sunset, it just goes right there.” He points to the path the sun will take as it sets, spilling its rays on the side of the mountain.

“You can’t see it from here, but across the way, you know where Teen Challenge is? The hill that is on . . . I believe that is katswiw or the Little Bird. It was a shrine hill. This all is a sacred area….ka’axtawaq h it means North Wind Place, and you can feel why, the breeze is pretty constant here. It’s where the interior climate meets the Ventura River and the coastal climate because everything narrows down here.”

ka’axtawaqʰ | North Wind Place

Passing a row of homes along the bike path, we continued.

“Somewhere in here there was a sacred sycamore tree, the Spanish called it Aliso del Viento, the Wind Sycamore...There are a few of these that we know about. One is a sacred sycamore tree up the Santa Clara River near kamulos, today called Camulos named for the California Juniper. The area is sacred, not just the tree. Just as a cave is a sacred place, not just the paintings... The sycamore has a branch growing out to the west and they train it to form like an arch,” he said, bending his arm at the elbow. “And this particular sycamore had a big cavity, in it there was an . . . anthropomorphic effigy made of wood, adorned with feathers and sqap, feather bouquets hanging upside down around the effigy. We dance with those. There were baskets all around the feet of the effigy in which people would deposit offerings...of seeds, shell bead money, later metal money, all sorts of things. Pine nuts, acorns.”

“[The effigy] was of the deity called slow̓, which is Golden Eagle, and he holds up the upper world, and when his wings go flapping up and down, that’s what gives us the phases of the moon. He’s kind of part nered up with the sun. Slow̓ is also a word used to describe the leader of a village,” he said, sweeping his arm through the air indicating the area southeast of where he stood. “Where Juan de Jesus Tumamait, leader of the Mission Indians during the transition between Mexico and America lived was called kaspat kaslow̓, The Eagle’s Nest. Rather than the name of the place, it signified the seat of power and could move.”

As for where the Wind Sycamore is today, “a man purchased the land and planted apricots, he supposedly cut it down. It doesn’ t matter anymore, the whole place is sacred . . . ka’axtawaq h | The North Wind Place the spirit is there to pray to.”

koyo Creek and mišopšno

“You know heading up to Santa Ana Road? The second bridge . . . it crosses Koyo Creek. The name of that place is koyo and Fernando

But often, Vestuto explained, Librado’s definitions are not translations of the word, but a description of significance. “He said that mišopšno | Carpinteria, meant correspon dence. . . . mišopšno is at one end of the trail and Koyo is at the other and they correspond to one another as points of beginning and end . . . The main thoroughfare, they would take a left up Casitas Canyon which is now a lake. Probably the trail hugged the western side of the canyon. Established roads [today] are where we would walk. koyo has been trans formed to Coyote Creek by the Americans.”

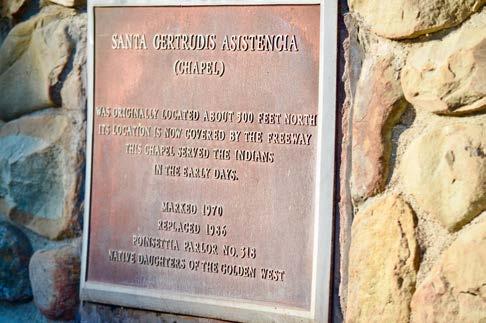

“The mission acquisitioned Canada Lar ga to support the mission. Ranching was done here, just down the river there.” Vestuto explained. “Cow and sheep ranching and agriculture. They built a chapel here called Santa Gertrudis . . . it served as a place where people could attend mass on Sunday who had to stay here and work and couldn’t go to the mission. The chapel was also built to compete with the sycamore tree.”

“When the mission was destroyed by an earthquake everyone fled for fear of a tsunami . . . I think they stayed up here for six to eight months. That is why they called this Casitas, because of all the little Indian homes . . . that was probably between 1820 and 1840.”

Vestuto pointed toward Canada Larga, saying, “You know where the aqueduct is?” The Chumash people built the aqueduct for supplying water to the mission. “Tule Creek... way up [highway] 33 where Tule creek and Sespe Creek meet, it’s a basket-weavers shopping mall, everything is there. Juncus balticus, sumac, willow, dogbane. Dogbane is cordage material, you have to go at different times of the year. My friend thinks it was a very well-tended area on purpose and just hasn’t been taken care of for 100 years or so. Everything is kind of choked, we need to do a lot of cleaning of the area to make sure it can grow back.”

He also pointed out a tall plant, with slen der dark green leaves. “That’s laurel sumac, it grows everywhere.” It has evolved with dozens of species of moths, butterflies and other insects, and was used by the Chumash to make tea and flour .

“That is salt bush,” he said, indicating an attractive, grey-green bush with white flowers that does, indeed, taste very salty. “There’s a village named simom̓o, after this plant [mo]; they were right next to each other.. muwu means ocean or any large body of water, it might refer to the estuary there at Pt. Mugu. The name of the mountain that goes down into the ocean [there} is called lulapin.”

Lulapin Confederacy

“The word lulapin is a combination of two words. lu- comes from aluše’eš, inland people, and -pin, federacy included the Purisemeño speaking people, Ineseño (the Santa Ynez Valley people), Barbareño (Santa Barbara area), the people from the islands, Cruzeños and Ventureños.”

“So it was a confederacy of people across language lines,” he said. “The closest thing to a national term for our people... There was a leader, halašu, ruled from about Dos Pueblos all the way to Pt. Mugu he practiced capital punishment. He killed a woman for adultery, and the people did not like that. It caused a big ruckus. When he died, they appealed to his son to be their leader and do away with capital punishment. There was a reformation of the social structure, and I believe that was the beginning of the Lulapin confederacy.

“All these villages were autonomous, they have their captains, chiefs who coordinate trade with other captains. They had their ’antap, Indian doctors, those who enter the ceremonial enclosure..there were 12 ’antap and 8 šan. These people are independent of the captains of the village. The šan were like roving ’antap and would tie all the satellite villages to the scene. And together they form a group called the ‘Twenty’, which is like a

A pool in the Ventura River surrounded by willows, cattails and sycamores. badger, referring to the Librado said it meant beginning.” a verb meaning ’of movement along the

Librado’s Chumash name was kitsepawit, coast,’ refers to the coastal and island peo he was born in 1838 in San Buevaventura. ple. it’s a really interesting word. There was In his 70s he shared the language and culture an epoch of time that ended when the Spanof the Chumash people with John P. Harish came,” Vestuto continued. “They first rington, a linguist and ethnographer who was came in 1542. And we had vast trade routes. compiling information on Chumash history . I’m sure we learned of what was going on The interviews with Librado resulted in some in the southwest with the Spanish coming 300,000 pages of notes. Librado died in 1915 up from Mexico at Santa Barbara Cottage Hospital and he is into the pueblos. buried at Calvary Cemetery in Santa Barbara. The [Chumash] con

body, like Congress.”

Distinguishing fact from myth

The term Chumash is a misnomer, a mainlanders’ name for the people on the

islands. The mainlanders called Santa Cruz Island mitšumaš meaning place of the makers of shell bead money.

According to Vestuto, “’aɬtšum is our word for shell bead money. And tšumaš |

The plaque memorializing the Santa Gertrudis chapel along Highway 33.

humash are makers of shell bead money. And Amercians just applied it to everyone in our language family – which is huge. Six distinct languages from San Luis Obispo to Bakersfield, down to Malibu and to the island. But it’s a misnomer, the victors write the history and you can tell when they don’t really care to know things.”

“Kwaiyin, the man the people asked to do away with capital punishment . . . He served kind of like an ombudsman. He was all for the people; he would be the last word, a very wise and respected person.

Looking back to the land, we moved down another dirt trail that meanders around trees like the stories being shared.

“There are big pools down here, a beautiful cottonwood tree, too,” Vestuto mused. “The roots have turned into trunks, it’s really cool. This plant is called mule fat. We would make arrow shafts and fire sticks out of these.”

We then turn onto another trail which opens to another large pool in the Ventura River.

“This is a huge pool, it’s marvelous!” he exclaimed. “Look at the fish, look how many there are. They are not all going to make it, but they have a fighting chance.”

As a small dark bird flew by, Vestuto noted, “That’s k h sen. It’s a mudhen, in our language it also means messenger.”

Some questions remain

We started discussing other places nearby. Kašoxšoɬ kawǝ | Deer Urine Spring, which Vestuto hypothesized might have been a cold sulphur spring. Kanawaya kakuw | Hanging Oak along Ventura Avenue — named for the oaks growing, and seeming to hang from the hillsides.

He emphasized that sounds in mitsqanaqan̓, are very important. A subtle difference in sound can have wildly different meanings.

“It’s really important, the difference between the sounds. If you say suyawaha, you say ‘I love you I love, or prize, or care for’ but if you say suyawaxa, you say I have to go number two,” Vestuto said with a chuckle.

We started our walk back to the overpass. A cooper hawk sends a call on the wind and lands, claiming the peak of a telephone pole for a perch to survey ka’axtawaq h | North Wind Place.

Regardless of the names these places wear now, even the experience of hearing the names said builds an experiential sense of place, and a connection to the people here

Looking north up the Ventura River. Smaller photos of native inhabitants, young gopher snake, (clockwise) black walnut, mugwort and mule fat.

long before us.

To contact Matthew Vestuto for a walking place name tour in the Ventura River Watershed email mvestuto@ gmail.com. For information on the upcoming publishing of these and other placename stories follow on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/iskiliwil or email iskiliwil@ gmail.com For more information on Advocates for Indigenous Language Survival visit: www.aicls.org