5 minute read

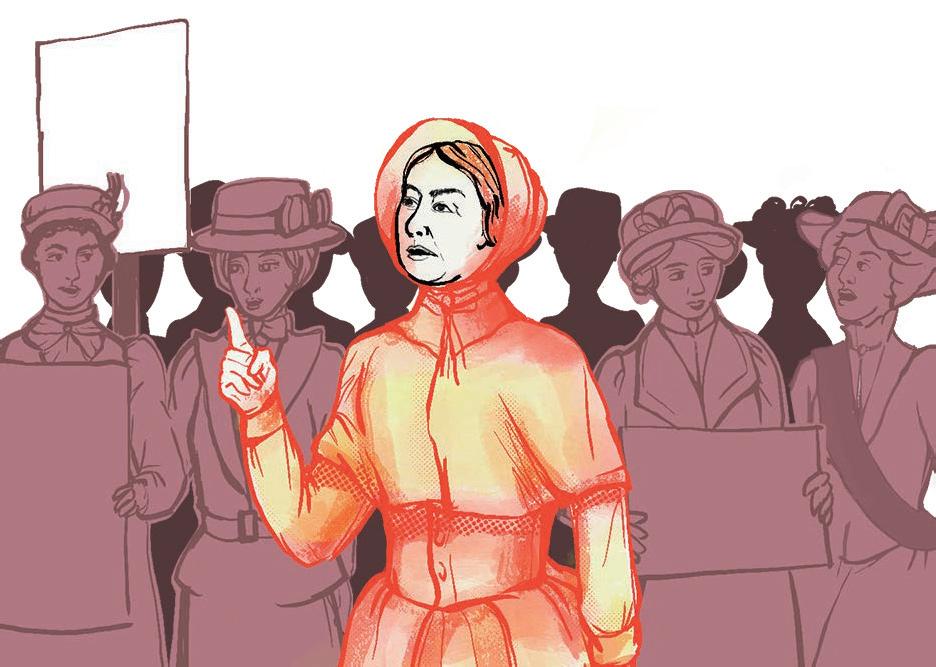

Elizabeth Cady Stanton

Advertisement

Chapter III ELIZABETH CADY STANTON

Seventytwo years prior to the 19th Amendment, Elizabeth Cady Stanton helped organize the Seneca Falls Convention, considered by many to be the beginning of the women’s suffrage movement in the United States. Her keynote address unveiled the “Declaration of Sentiments,” which offered edits to the Declaration of Independence. Namely, asserting that all men — and women — are created equal, and calling out the inequality women faced, from divorce laws to restricting educational opportunities.

“We have met here today to discuss our rights and wrongs, civil and political, and not, as some have supposed, to go into the detail of social life alone.” ELIZABETH CADY STANTON

“Voices were the visitors and advisers of Joan of Arc. Do not ‘voices’ come to us daily from the haunts of poverty, sorrow, degradation, and despair, already too long unheeded? Now is the time for the women of this country, if they would save our free institutions, to defend the right, to buckle on the armor that can best resist the keenest weapons of the enemy — contempt and ridicule. The same religious enthusiasm that nerved Joan of Arc to her work nerves us to ours.”

From a young age, Elizabeth rejected the traditional gender roles placed on her and became not only a suffragist, but an abolitionist and an activist fighting for women’s health, wealth and educational opportunities. She would write in her autobiography that she felt discontented with the plight of women. She hated the constant supervision and being placed into the mold of being a mother, wife and housekeeper. She wrote essays and speeches, hoping to break that mold.

“… Strange as it may seem to many, we now demand our right to vote according to the declaration of the government under which we live. … The right is ours. Have it, we must. Use it, we will. The pens, the tongues, the fortunes, the indomitable wills of many women are already pledged to secure this right. The great truth that no just government can be formed without the consent of the governed we shall echo and re-echo in the ears of the unjust judge, until by continual coming we shall weary him.”

This suffragist with a sharp pen became a force in the suffrage movement, splitting her time between writing essays and recruiting for the cause with raising her seven children. During that time, Elizabeth formed a friendship with Susan B. Anthony. Susan visited Elizabeth often in her home in Seneca Falls and would help look after the children so Elizabeth could write speeches in support of suffrage. Susan then traveled the country giving those speeches.

Women winning the right to vote was just one aspect of her fight for equality. Elizabeth also took to the streets of New York City with petitions supporting the New York Married Women’s Property Act, advocating for the rights of married women, who could not own property or earn and manage their own money.

“… We are assembled to protest against a form of government existing without the consent of the governed — to declare our right to be free as man is free, to be represented in the government which we are taxed to support, to have such disgraceful laws as give man the power to chastise and imprison his wife, to take the wages which she earns, the property which she inherits, and, in case of separation, the children of her love; laws which make her the mere dependent on his bounty.”

Elizabeth’s beliefs and opinions could be controversial. In a move that split the suffrage movement in two, she and Susan opposed the 15th Amendment, which gave black men the right to vote, because it did not extend that right to women. She published a controversial book, the “Woman’s Bible,” in which she argued religion was a form of oppression against women. She continued writing until she died in 1902, 18 years before women would win the right to vote.