12 minute read

Stirling Moss

SIR STIRLING MOSS 1929-2020

Words: Philip Strickland Photos: BMW, JD Classics, Lotus, Maserati, Mercedes, Gareth Tarr, WSM

Few people in history can truly claim that their name has become so assimilated in the minds of the public that the mere mention of it evokes an instant recognition of the person, his sport and all he stood for with his skill and sportsmanship. In fact, so connected was that name to the image of speed, that it became a badge of honour for any errant motorist to be stopped by the Police with the admonition: ‘Who do you think you are, Stirling Moss?’ When this actually happened to Stirling, as he left Buckingham Palace upon receiving his Knighthood, he replied to the scolding officer: ‘Sir Stirling, actually.’

Stirling Craufurd Moss was born on the 17 September, 1929 to Aileen and Alfred Moss who lived in London. His mother had been a successful rally driver, having herself been encouraged to compete by her parents when lady drivers were still very much a novelty. Alfred, a successful dentist, also had the competitive urge and was a regular competitor at Brooklands and had even competed in the 1924 Indianapolis 500-mile race. With such parents, it was inevitable he would compete in cars once he had graduated from horses, on which he displayed a skill to rival his sister Patricia who was seven years his junior.

Like many would-be racing drivers, Stirling began early and from the age of seven he would drive an old Austin around the family orchard at their home in Tring. The truth was that although he bettered Pat in junior horse trials, he actually hated the things and rode only at his mother’s encouragement. Switching from four legs to four wheels came with the acquisition of

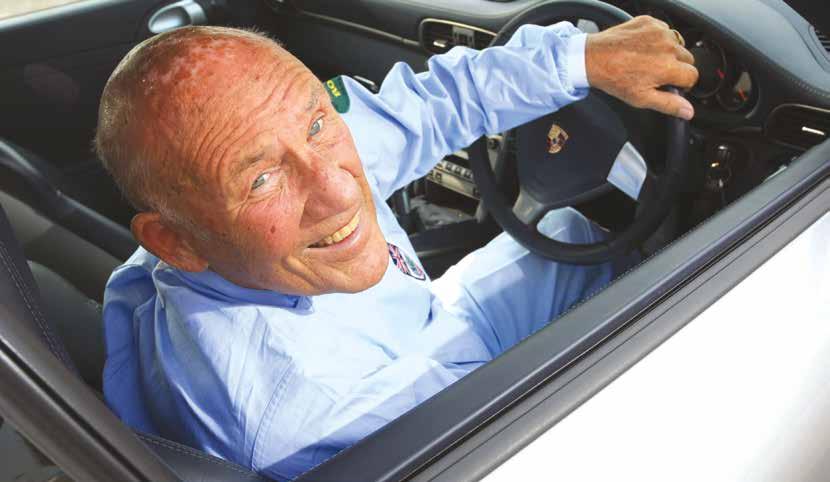

Even after injuring himself when he fell down a lift shaft at 80-years old, Sir Stirling remained a keen competitor in historic racing.

his first racing car, a Cooper 500. Soon he was winning, despite initial resistance from parents who understood the inherent risks more than most.

Early years

By the age of 19, Stirling was already a force to be reckoned with, often winning several races at a single meeting in a range of cars. It seemed he could make anything go faster than it had ever been driven before and displayed a remarkable smoothness, partly inspired by the relaxed driving style of Dr Giuseppe Farina, the first Formula One World Champion. By 1949, it was clear Stirling was going to earn his living as a racing driver. He had been briefly employed in an hotel, but neither this work, study or dreary office life appealed in the slightest. A chance meeting with Ken Gregory while he was still working in the hotel led to a lifelong friendship. Ken acted as guide and manager for much of Stirling’s career and it was he who encouraged Stirling to enter the budding Formula 3 Championship, for which the Cooper was designed.

Soon, he began racing on the Continent in both the Cooper and an HWM and quickly came to the attention of the factory teams and that led to an offer from Enzo Ferrari to drive for him in 1951. Stirling jumped at the chance and duly made his way to Maranello, only to discover on arrival that his seat had been taken by local man Piero Taruffi. Stirling never spoke to Enzo Ferrari for 10 years and said of him ‘He is not a gentleman’. Whether this was a misunderstanding or gamesmanship will never be known, but it may have been a critical moment lost in Stirling’s career.

As a direct consequence of this experience, Stirling put all his energy into driving for only British teams. This developed a close and fruitful relationship with Rob Walker, for whom Moss drove many times. In all, Moss entered 67 Grands Prix, starting 66 and winning 16 of them. This was at a time when there were often just eight or nine races in a season, leaving the now highly paid and highly rated Moss to compete in sportscars, saloons and other types of competitive endurance events, such as the Mille Miglia, the Targa Florio and Land Speed record attempts with MG at Bonneville.

It was in a Jaguar C-type equipped with a new type of brake system that Moss, partnered by Norman Dewis, took part in the 1952 Mille Miglia. Testing the pioneering disc brake, Moss was

The tiny Lotus 18 may have not have been as powerful as its rivals, but Stirling Moss used its superb handling to great effect and won the 1960 Monaco Grand Prix.

running in third place when they hit a rock and damaged the suspension. That performance brought him to the attention of the legendary Alfred Neubauer, team manager for Mercedes, who offered to take Moss on to partner Fangio for the 1955 season.

Success and retirement

Ken Gregory told the wonderful story of their trip to Stuttgart at the end of 1954 to discuss the Mercedes offer. Between them, they hatched a plan to ask for far more than they felt Moss was ever likely to be paid, thinking that if they aimed high, the offer might fall close to what they really wanted. When the opening offer was made by Neubauer, Moss nearly fell off his chair. So astonished were they both that Neubauer mistakenly thought he had insulted them and greatly increased the figure. It was the highest fee he had received at that time and by 1961 Moss was Britain’s highest paid sportsman.

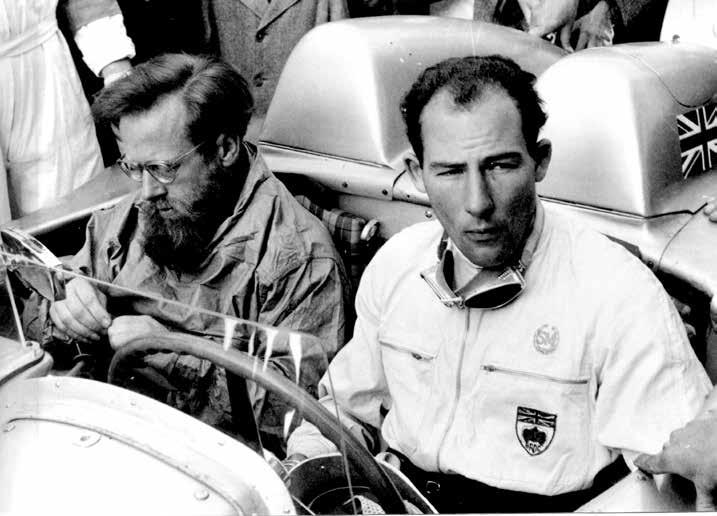

Now with Mercedes, Moss was entered for the 1955 Mille Miglia and took his old friend Denis Jenkinson as navigator, who had devised a roll-map display to read the pace notes. They won the race at a record average of almost 100mph (97.95mph)

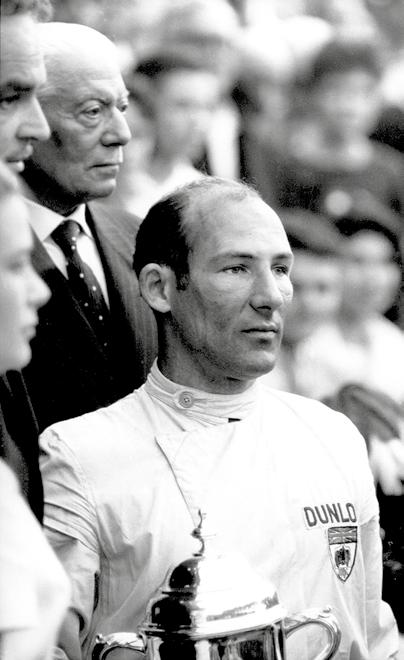

Always professional, Stirling Moss manages to look calm and composed after stepping out of the Lotus 18 following his win in the 1960 Monaco Grand Prix.

over 993 miles. Later that year, Moss achieved his first Formula One Grand Prix

victory at Aintree in the British Grand Prix, beating team-mate Fangio by a whisker.

Other notable performances set him apart, such as his drive in the German Grand Prix of 1961, a race where his underpowered Lotus 21 was pitched against the might of Ferrari with their immaculate and novel shark-nosed 156 model. Over 15 laps of the Nürburgring Nordschlief, he won by 21 seconds in the rain. This drive emulated his earlier all-conquering drive in the same Rob Walker-entered Lotus at Monaco, where he

ran the car without side panels to combat the intense heat and overpowered a mighty assault from the Ferraris of Ginther, Hill and von Trips.

Ironically, the German Grand Prix was to be his last F1 victory and the last time he would compete against von Trips, who died in the next race at Monza. Driving at the Easter Monday meeting at Goodwood the following spring, Moss once again found himself in an underpowered Lotus 21 fighting a new rival, Graham Hill who was in the ‘Smokestack’ BRM P57 V8. It was the Glover Trophy meeting held on St Georges Day. Moss had repeated gearbox issues and was a lap down as he came up behind eventual winner Hill entering St Mary’s. What happened next has never been explained.

Moss had no recollection of his neardeath impact with the bank on the outside of the bend. Left with severe head injuries and other wounds, Moss was to carry both the scars and the physical consequences of this career-wrecking accident to the end. His long fight to recover after being in a coma for a month was followed by a year of rehabilitation. For the first time in his

life, it left him unemployed and effectively unskilled for any other role. Yet he filled the void as only a true champion might by reinventing himself, leading to a brand name that remained in high demand until ill health struck in 2016.

Brooklands role

It was his erstwhile business partner, Ian McGregor, who joined me on the Brooklands Trust Members Committee as Vice Chairman, who thought we might approach Stirling to become our President. Stirling loved the idea of an attachment to the circuit that had given his father so

The smooth style that marked out Moss and made him so difficult to beat is clearly visible as he heads towards victory in Monaco in 1960 aboard the Lotus 18.

much pleasure and success, and he willingly served his role with gusto and honour.

Stirling always had to endure the label that he was the ‘greatest driver never to have won the World Championship’. Such a bald description belied the fact that he could have, and perhaps ought to have been, a triple World Champion. In the years 1958, 1959 and 1960, it was only bad luck that robbed him of just reward for his obvious superiority over those who were crowned in his place.

In truth, Stirling was the most successful Grand Prix driver by far in 1958, yet it was Hawthorn who took the title with a single win to Moss’ four. This came about because of a moral stand taken by Stirling following the end of the Portuguese Grand Prix that year. Moss was comfortably heading for victory in the race by a huge margin and with it the World Championship, when he came up to lap second placed man Hawthorn. When Hawthorn spun and stopped as they both ascended a hill, Hawthorn allowed his Ferrari to roll on the

adjoining pavement in an attempt to bumpstart the engine. This meant he was moving against the direction of the circuit, a heinous crime in motor racing, and disqualification ensued. This was a critical decision, for if Hawthorn could keep his second place, he would have been well placed to take the championship. Hawthorn was encouraged by Moss to appeal the disqualification and Stirling appeared at the hearing to support his rival, arguing that the Ferrari had been on the pavement when rolling against the traffic and thus did not contravene the

that night Hawthorn effectively won back the points that would eventually give him the World Championship from Moss by a single point.

Years later I, like many before me, asked Stirling if he had any regrets about that decision. He had none. He said he could never have countenanced being awarded a Championship based on such circumstances. To him it was essential to play by the rules.

During his 14-year career, Stirling had seven major accidents on the track and one major accident off it. Of the racing incidents, he was somewhat dismissive, suggesting that if you are a racer, then accidents will happen. Such a philosophy was never intended to apply to climbing into a domestic lift. In March 2010, at his gadget-filled home in Mayfair where he had lived for much of his professional life, he fell three storeys when he entered the lift with some luggage, the lift carriage having failed to arrive. Once again, Stirling was to confound the medical world by his rate of recovery. When I visited him a few days after the accident, he was convalescing from surgery on both legs and expected more on his cracked vertebrae. I asked him what the prognosis might be and he replied: ‘I don’t know what the doctors have in mind, but I’m racing in May.’ And he did, even though he was more than 80-years old.

Perhaps the most remarkable quality Stirling possessed, in addition to his exceptional poise and balance in a car, was his accessibility. He was never stuffy nor demanding. He wore his celebrity lightly. He insisted that his telephone number and full address be listed in the telephone directory for all to read. For him, the pleasure of meeting enthusiasts, fellow drivers and the public kept him engaged and young. His skill behind the wheel never deserted him, although when he finally stopped racing it was because he felt he could no longer keep up with those one third of his age. Stirling was an Englishman to the core, which perhaps dictated his steadfast loyalty to British teams when more competitive drives were available. It perhaps explained his enduring love of the sport that defined him, as he defined it. For him, Brooklands

embodied the essence of British values even though he never raced here. Stirling was finally beaten by an infection contracted in December 2016. Were it not for the remarkable care and love he received from his beloved wife Susie, who he married in 1980, his son Elliot and a brilliant nursing team, he may never have survived to Easter Sunday, 2020. As Susie so gently put it: ‘In the end, it was one lap too many.’

Brooklands Trust Members were proud and honoured to have as their President a man of whom it might also be said: ‘Stirling Moss was the greatest driver never to have raced at Brooklands.’

A love of racing, motorsport and people made Sir Stirling Moss a household name and he was very proud to be President of the Brooklands Trust Members.