P R A X I S

20.2 Influences in the Writing Center: From Micro to Macro

VOL.

VOL.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

COLUMNS

From the Editors: Influences in the Writing Center: From Micro to Macro

Kiara Walker and Kaitlin Passafiume

The Art and Craft of Sentence-Level Choices

Michelle Cohen

FOCUS ARTICLES

What’s Your Plan for the Consultation? Examining Alignment between Tutorial Plans and Consultations among Writing Tutors Using the Read/Plan-Ahead Tutoring Method

Diana Awad Scrocco

Faculty Writing Groups for Writing Center Professionals: Rethinking Scholarly Productivity

Kara Poe Alexander, Erin M. Andersen, Julia Bleakney, and Jennifer Smith Daniel

A Model for Infusing a Creative Writing Classroom with Writing Center Pedagogy

Kelle Alden

Reading the Online Writing Center: The Affordances and Constraints of WCOnline

Pratistha Bhattarai, Aaron Colton, Eun-hae Kim, Amber Manning, Eliana Schonberg, and Xuanyu Zhou

What Our Tutors Know: The Advantages of Small Campus Tutoring Centers

Ana Wetzl, Pam Lieske, and Mahli Mechenbier

Advocates for Education in Prison-Based Writing Centers

Julie Wilson

Kelle Alden, PhD is an Assistant Professor of English and Director of the Hortense Parrish Writing Center at The University of Tennessee at Martin.

Kara Poe Alexander, PhD is Professor of English in Professional Writing and Rhetoric and Director of the University Writing Center at Baylor University. She is also the submissions editor for Literacy in Composition Studies. Her work has appeared in College Composition and Communication, College English, Composition Forum, Composition Studies, Computers and Composition, Journal of Business and Technical Writing, Literacy in Composition Studies, Rhetoric Review, Technical Communication Quarterly, and other scholarly journals and edited collections. She also has a co-edited book, Multimodal Composition and Writing Transfer, forthcoming with Utah State University Press.

Erin M. Andersen, PhD is an Associate Professor of Writing in the Business, Media, and Writing department and Director of the Writing Collaboratory at Centenary University where she teaches first-year writing, queer and feminist theory, and tutor training classes. Her current research interests focus on the intersections of writing centers, assemblage theory, assessment, and social justice. Her work has been published in Writing Program Administration, Peitho, and WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship.

Pratistha Bhattarai is a Ph.D. candidate in the Program in Literature at Duke University.

Julia Bleakney, PhD is Director of The Writing Center, within the Center for Writing Excellence, and Associate Professor of English at Elon University, North Carolina. Her research focuses on writing center tutor education, student leadership, and writing beyond the university. Her publications include a co-edited book, Writing Beyond the University: Preparing Lifelong Writers for Lifewide Writing as well as articles in The Writing Center Journal, WLN: A Journal of Writing Center Scholarship, Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, and Composition Forum.

Michelle Cohen, PhD is an assistant professor and faculty tutor in the Center for Academic Excellence/Writing Center at the Medical University of South Carolina. She has worked in writing centers since 2010. Her research interests include writing center theory, multimodal composition, and style.

Aaron Colton, PhD is a lecturer in writing studies and the assistant director of the TWP Writing Studio at Duke University. He is currently researching writer’s block both in the classroom and in fictional representations.

Jennifer Smith Daniel, MA is Director of Writing Center and Writing Across the Curriculum Programs at Queens University of Charlotte. Her research focuses on engaged pedagogies, rhetoric and literacy, tutor education, mentorship, and first-year writing. She is currently the chair of the SWCA CARE certification committee. Currently, she is working on a dissertation in which she proposes a method for assessing how tutors’ ecological pedagogies impact their tutoring praxis. She has published in Community Literacy Journal and MacMillan Learning’s Tiny Teaching Stories

Eun-hae Kim is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of English at Duke University.

Pam Lieske, PhD is a Professor of English at the Trumbull campus of Kent State University at Trumbull where she teaches courses in writing and literature. A former coordinator of English at her campus, she is interested in, among other things, issues related to distance learning and teacher and tutor training.

Amber Manning is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of English at Duke University.

Mahli Mechenbier, MA & JD teaches Technical Writing, Professional Writing, and College Writing at Kent State University at Geauga as a three-year-renewable Senior Lecturer. She was a member of NCTE’s Committee for Effective Practices for Online Writing Instruction and was an editor for the OWI’s Open Resource (2013 – 2016). Her research focuses on how academic administrations manage distance learning and the intellectual property rights of contingent faculty.

Eliana Schonberg, PhD is an associate professor of the practice in writing studies and the director of the TWP Writing Studio at Duke University. Her current research centers on knowledge transfer in writing centers and writing fellows programs and on changing conceptions of time in writing center studies.

Diana Lin Awad Scrocco, PhD is an associate professor of English at Youngstown State University where she directs the Public and Professional Writing Program and teaches professional writing, composition, and pedagogy. Her recent research has appeared in Programmatic Perspectives, Journal of Argumentation in Context, and Communication and Medicine. She earned a Ph.D. in Literacy, Rhetoric, and Social Practice from Kent State University before collaborating with Joanna Wolfe at Carnegie Mellon University to establish the first communication center on the campus. Address for correspondence: Department of English, Youngstown State University, One University Plaza, Youngstown, OH 44555. Email: dlawadscrocco@ysu.edu.

Ana Wetzl, PhD is Associate Professor of English at Kent State University at Trumbull where she specializes in first-year composition, specifically developmental writing. She was the English Coordinator for the campus Learning Center between 2011 and 2020. Her research focuses on the intersection between first and second language writing and tutoring center work.

Julie Wilson, PhD holds a doctorate in Education from UNC-Chapel Hill and directs the Writing Studio at Warren Wilson College.

Xuanyu Zhou is a first-year clinical epidemiology master's student at Stanford University with an infectious disease concentration.

In Praxis issues of the recent past, we (Kiara and Kaitlin) have aimed to shine a light on the many ways that writing center work resounds throughout university life, in and beyond the walls of the center. We have recognized how the writing center guides students towards success, enjoining the wider educational system to follow our lead on many pressing issues like inclusion. We have celebrated the transformative nature of writing center work, uncovering how our practices help not only writers to transform, but how writing center administrators and faculty alike can evolve through the work that we do.

In this issue, we celebrate the micro-influences that writing center work produces, even as our practices reach outside of the buildings that house us. The authors included in this edition echo this sentiment, as evidenced by their varied qualitative and quantitative studies. There is one thing each author communicates invariably, despite the plethora of themes and formats you will find herein. These practitioners express the influential nature of writing center work, beginning with the microcosmic element of the sentence itself. This fragment of a writer’s work begins its journey on paper, reverberating on each new level until our purpose is felt outside of the wider educational institution. Closing the issue, writing center pedagogy informs prison curricula as a true testament to the resounding impact of writing center work.

In her column “The Art and Craft of SentenceLevel Choices,” Michelle Cohen kicks off the current issue as she blurs the line between art and craft. The author advocates for the micro, exposing LOCs (lowerorder concerns) as that methodology which can make artists out of writers. Cohen’s metaphor comparing sentence construction to ceramics does the work of placing sentence craft squarely in the artistic realm, illustrating “the inherent relationship between form and content.”

Next, Diana Awad Scrocco widens the lens in her focus article “What’s Your Plan for the Consultation? Examining Alignment Between Tutorial Plans and Consultations Among Writing Tutors Using the Read/Plan-Ahead Tutoring Method.” In this case study, Scrocco exposes a tension between consultation agenda setting and use of the read/plan-ahead method, used primarily when tutors encounter advanced writing or

Kaitlin Passafiume University of Texas at Austin praxisuwc@gmail.comunfamiliar topics. She examines the benefits and drawbacks of each consultation priority, looking at thirteen separate consultation moments where each method can be found at work. The author gives due consideration to both the agenda-setting and read/planahead strategies, ultimately reminding us that writers should unwaveringly be the center of every consultation choice that a tutor makes.

In “Faculty Writing Groups for Writing Center Professionals: Rethinking Scholarly Productivity,” the authors take their experiences as writing center professionals into a writing group. Through this group, authors Kara Poe Alexander, Erin M. Andersen, Julia Bleakney, and Jennifer Smith Daniel come to better understand their own approaches and possibilities when considering scholarly work. The authors’ insights in three areas of productivity scholarly and intellectual, professionalization and mentoring, and social support are of use for other writing center professionals making the case about the value of their work that may not fit into common notions of scholarly productivity.

Kelle Alden follows in “A Model for Infusing a Creative Writing Classroom with Writing Center Pedagogy,” empowering the very methodology that fuels our centers to inspire greater scholarly collaborations. The author applies writing center theory using statistical data in an unaffiliated writing class, showing one example of how our discoveries can benefit the institution beyond the wring center itself.

Bhattarai et al follow, backing farther away from the center’s walls as they present “Reading the Online Writing Center: The Affordances and Constraints of WCOnline.” This focus on virtual practice is timely, considering an educational shift to incorporate technology and answer demands for multidimensional curriculum. Pratistha Bhattarai, Aaron Colton, Eun-hae Kim, Amber Manning, Eliana Schonberg, and Xuanyu Zhou highlight the ways in which pandemic trauma forced educators to catch up to the demands of a digital society. In much the same way that pen-and-paper academia values a book review, these authors offer “critical digital pedagogy,” creating a guideline for the oft discussed WCOnline. This collective employs an analytical approach to the platform’s benefits and shortcomings, ultimately suggesting best practices to

maximize this online tool’s usefulness for writing center work.

Next in “What Our Tutors Know: The Advantages of Small Campus Tutoring Centers,” Ana Wetzl, Mahli Mechenbier, and Pam Lieske take us to a set of regional campuses in Ohio, arguing for the value of writing centers in these spaces in response to rise of eTutoring. By surveying tutors at the featured regional campuses, the authors gain insight into the communities of practice developed there and the possibilities of on-campus tutoring that are not likely to be reproduced in eTutoring spaces and practices. Based on their survey, the authors advocate for preserving and maintaining writing centers on regional campuses, arguing for the benefits that can be had in communities of practice present in local, face-to-face interactions.

Julie Wilson closes our issue by looking at writing center collaborative work in an often-disregarded space for intellectual and educational experiences. In “Advocates for Education in Prison-Based Writing Centers,” Wilson presents her findings from developing a writing studio in a women’s prison. By using a qualitative action research design, Wilson was able to design and redesign a supportive writing center that took into consideration student experience and the knowledge of system impacted scholars. Based on the study, Wilson encourages writing center practitioners to genuinely seek out, center, and respond to student advocacy and students’ ability to recognize their own needs.

In the spirit of employing our work outside the writing center and ushering in new practices and policies, it is with excitement for the future that we bid goodbye to our co-editor Kaitlin Passafiume, as she transitions into a new role. In this next phase, she will undoubtedly rely on what writing center practice has taught her even as she works to promote decolonizing versions of democracy in Latin America. She signs off this chapter, humbled by the potency of writing theory and policy to transcend sentence creation, the walls of our centers, our educational institutions, and our nations’ boundaries, leaving us with the following message:

“The past two years have served to etch the value of writing center work beyond merely helping writers help themselves. The University Writing Center at UT and our premier journal Praxis have given me a greater purpose in academia, and the diverse roles I have been able to play have afforded me a complexity that shall shape my future career path. Each author and collaborator have taught me new applications for our work, and I am forever grateful for your continued

contributions, even as we continue to tap away and toss new thoughts into the writing arena.”

When I was in graduate school, I had the good fortune of finding a home for my studio art practice in the university’s ceramics facilities. I worked on my sculptures in a space primarily dedicated to advanced undergraduate ceramics students, and I joined in their critiques.

A sensitive issue that would often arise was the tension between art and craft. Ceramicists have to think seriously about this binary because we work in what is often called a “craft medium.” In the art world, that often means justifying one’s own legitimacy. One student devoted his work to upsetting the art-craft distinction, intentionally breaking his mugs or covering them in sharp spikes. In critique, he would ask, “If I take away function, then is it art?” Another student painstakingly carved her vessels with mandala patterns. In critiques, she bristled when her peers tried to navigate delicately around the word craft: “Why would I be offended? I’m a craftsperson. That doesn’t mean I’m not an artist.”

I watched as these students questioned a familiar hierarchy in the art world one where skill and function are seen as values of a mere hired hand, whereas the illustrious concept occupies the mind of a “true artist.” At the same time, I found these art-craft debates paralleling issues I encountered in my work as a compositionist, particularly in the writing center.

In the writing center, the division between hand and mind, between form and content, was mirrored in the distinction between higher order concerns (HOCs)1 and lower order (or “later order”) concerns (LOCs).2 When working with a client, I had been trained to prioritize “HOCs before LOCs,” dismissing sentence-level issues unless I noticed patterns of error or local obstructions to clarity. While this stratified approach to writing center sessions worked well for many students, I quickly found as many of us have that not all students want or need an exclusive focus on global concerns in order to improve as self-aware, rhetorically savvy writers.

Why weren’t we teaching the medium-specific knowledge that would help each student succeed in their rhetorical composing? When learning in a clay-based medium, I needed to understand at the very least the basic technical aspects: how to wedge the air bubbles out of clay so my piece wouldn’t blow up in the kiln; the

properties and application of glaze so as not to damage expensive equipment in firing; or how to throw basic shapes on the potter’s wheel so I could begin to experiment more with my own forms. These examples are not simple cases of “learning the rules before you can break them” to maintain the status-quo; rather, abiding by certain conventions of physics, chemistry, and craft tradition could mean the difference between producing a vitrified ceramic object and opening the kiln to find glaze-damaged shelves and piles of rubble. In sum, I had to understand the medium to produce the artistic outcome I wanted.

Words are a different medium than clay, of course intangible, shaped first and foremost by society rather than geology. Still, in rhetorical composing, skillful use of words is often integral to successful verbal communication. Yet, whether in my graduate program or in the writing center itself, I had received little formal training on helping writers with sentence-level concerns; these were all seemingly subsumed under a nebulous “grammar” umbrella or worse, currenttraditionalism and therefore tacitly positioned as the antithesis of rhetoric.

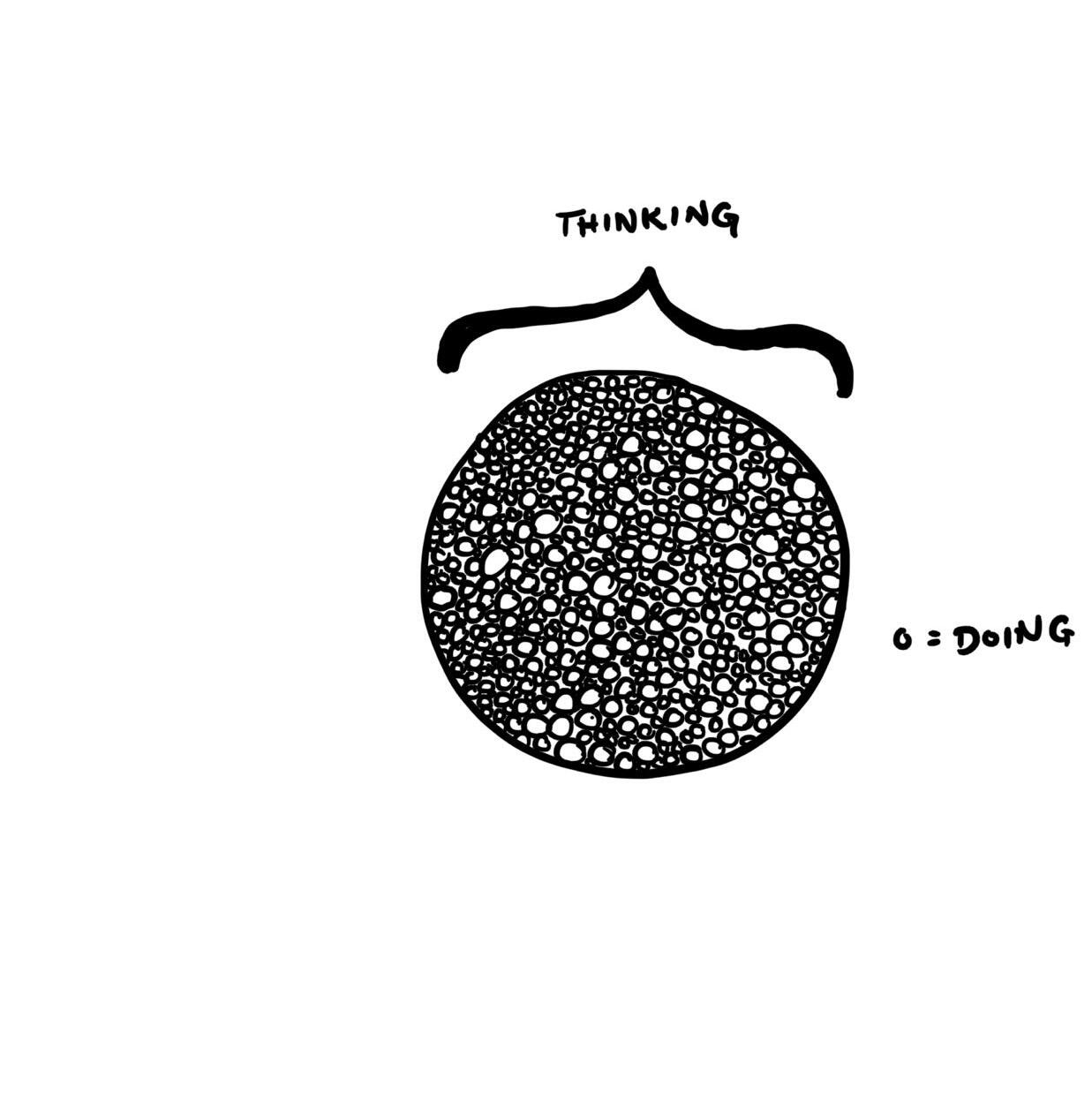

The musings and struggles that I encountered simultaneously in the ceramics studio and the writing center are woven into a larger tapestry of the contentform binary, one in which we separate out synergistic concepts, elevating thinking over doing, message over medium, and creativity over technical skill (see fig 1). Simply put, LOCs were seen as matters of “craft,” not “art.”

Before revising our approach to the concerns we’ve neglected, I think it important to note where these parallel binaries i.e., art/craft and HOCs/LOCs each came from. Both can be contextualized within historical power dynamics, and in both cases, we can read the dominant term (i.e., art and HOCs, respectively) as emerging to defend labor perceived as undervalued or marginalized. The earliest distinctions between art and craft have been dated back to the Italian Renaissance, when makers such as da Vinci and Vasari separated their work from the “manual labor” of guild workers to justify their intellectual labor (Rath 26-28; Rosati, 116). Public art historians remind us that artists at this time operated within a system of patronage; by

elevating their status, they sought secure respect and fair compensation for contracted work (Morelli; Harris & Zucker).

Similarly, the division between HOCs and LOCs seems to have emerged in part to justify the intellectual labor of writing center work. In 1984, Stephen North published “The Idea of a Writing Center,” pushing back against misconceptions that “a writing center can only be some sort of skills center, a fix-it shop” (435). The same year, Thomas Reigstad & Donald McAndrew introduced the terms HOCs and LOCs in their guide booklet Training Tutors for Writing Conferences This division allowed consultants to prioritize certain concerns over others in order to focus on the most “significant problems,” but also to relieve the consultant of “detect[ing] and correct[ing] all the problems” (Reigstad & McAndrew 26, emphasis in original) a worthy goal, and one we can update in the context of today’s writing center.

So how do we explore sentence-level pedagogies without reinforcing the age-old misconceptions of our work? I argue that it’s a two-fold shift: first, in how we view the relationship between HOCs and LOCs (perhaps better described as local and global concerns); and second, in training and pedagogical approach. The first shift leads to what I call an embrace of techné; the second, to an embrace of holistic consulting.

First, we must acknowledge the inherent relationship between form and content. In writing, we simply could not communicate our thoughts without the words on the page. Every word, punctuation, sentence, paragraph, and so forth marks a choice that helps construct and execute the larger concept. Therefore, I suggest a return to the classical concept of techné, what Susan Delagrange describes as an “incorporation of thinking and doing … a productive oscillation between knowledge in the head and knowledge in the hand” (35). Through a techné framework, writing center stakeholders can begin to see the interdependence of local and global concerns. The metaphor of techné positions writing as neither art nor craft exclusively, but as skillful creative labor, a marriage of thinking and doing. Embracing techné means breaking down the vertical hierarchy of the HOCs/LOCs binary (shown in fig. 1) and replacing it with a model wherein local choices are recognized as collectively constructing a global whole (see fig. 2).

This first shift implies a second: a holistic approach to writing consulting. Every writing center session necessarily requires prioritization; writers and consultants simply cannot attend to every choice made within a piece of writing. A HOCs/LOCs framework mitigates this overwhelming challenge by pre-sorting concerns for the consultant, anticipating those which will likely bear the most weight in revision and steering the session away from proofreading. This framework plays the odds, wagering that most writers in most situations will receive the greatest benefits from a bigpicture discussion of argument and organization.

While a more detailed and more advanced approach, a techné framework could yield a higher return when applied thoughtfully and creatively. By understanding the paper as an act of synthesis, we can focus on the most salient local instances (the “loadbearing sentences,” if you will) that come together to make a meaningful whole. This framework suggests that the consultant and the writer possess or can develop both the genius and skill (the artistry and craftsmanship) to select, discuss, and reimagine salient global and local decisions.

By providing consultants with a holistic theoretical foundation for their practice, we can above all embrace the writing center as a site for innovative composition pedagogy. As Jesse Kavadlo argues, “A return to language not just what students are trying to say, but the diction that they use to say it, and the relationship between what they say and how they say it seems just the sort of balanced approach that one-on-one tutoring and collaboration can foster” (218). When we delve into those concerns relegated as “lower” or “later,” we reimagine the writing center as a studio for medium exploration. I’m excited to see what we make.

1. Including big-picture concerns such as “thesis or focus; audience and purpose; organization; and development” (Purdue OWL).

2. Including concerns such as “sentence structure, punctuation, word choice, [and] spelling.” (Purdue OWL).

Delagrange, Susan H. Technologies of Wonder: Rhetorical Practice in a Digital World. E-book, Computers and

Composition Digital Press/Utah State UP, 2011, https://ccdigitalpress.org/book/wonder/

Harris, Beth, & Zucker, Steven. “What makes art valuable then and now?” Khan Academy, n.d., www.khanacademy.org/humanities/approaches-to-arthistory/questions-in-art-history/a/what-made-artvaluablethen-and-now Accessed 9 Jan. 2020.

Kavadlo, Jesse. “Tutoring Taboo: A Reconsideration of Style in the Writing Center.” Refiguring Prose Style: Possibilities for Writing Pedagogy, edited by T. R. Johnson & Thomas Pace, Utah State UP, 2005, pp. 215-226. Morelli, Laura. “What’s the difference between art and craft?” TedEd, Mar. 2014, https://lauramorelli.com/whats-the-differencebetween-art-craft/

North, Stephen M. “The Idea of a Writing Center.” College English, vol. 46, no. 5, 1984, pp. 433-446.

Purdue Online Writing Lab. “Higher Order Concerns (HOCs) and Lower Order Concerns (LOCs).” n.d., https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/mechani cs/hocs_and_locs.html, accesed 9 Jan. 2020.

Rath, Pragyan. The “I” and the “Eye”: The Verbal and Visual in Post-Renaissance Western Aesthetics. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011.

Reigstad, Thomas J. & McAndrew, Donald A. Training Tutors for Writing Conferences. ERIC Clearinghouse/National Council of Teachers of English, 1984, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED240589.pdf

Risatti, Howard. A Theory of Craft: Function and Aesthetic Expression. University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Writing center scholars and tutor-training manuals historically emphasize the importance of tutors and writers collaboratively negotiating consultation agendas to maintain writers’ ownership over their writing. However, when tutors encounter advanced student writers, writers from unfamiliar fields, or writers with complex linguistic repertoires, they may struggle to read student writing, identify writing issues, and negotiate effective, mutual agendas. One tool for navigating these challenges is the “read-ahead method” in which tutors read student writing in advance and prepare for consultations (Scrocco 10). While this method offers potential advantages, a brief survey reveals that some writing center administrators worry that tutors who read student writing in advance may hijack consultation agendas. This exploratory mixed-methods study examines thirteen tutor-supervisor planning conversations and subsequent consultations to assess the correspondence between tutors’ plans and consultations and to consider what factors may support or undermine writers’ agendas. Results suggest that tutors who use the read/plan-ahead method do not fervently push their planned agendas over writers’ agendas. However, very detailed or particularly vague pre-consultation planning may set tutors up for sessions that fail to negotiate and carry out cohesive, well-prioritized shared agendas. The most collaborative, coherent consultations in this study balance tutor and writer agendas. They begin with writers’ submitted concerns, identify high-priority global writing issues, engage in substantive agenda-setting with writers, explicitly link tutors’ plans with writers’ agendas, and abandon tutors’ plans when needed. The read/plan-ahead model works best when tutors remember to place writers at the heart of building, revising, and enacting consultation agendas.

In the writing consultation excerpt in figure 1 between a graduate student tutor and multilingual international graduate student 1 , the tutor opens with a common writing-center move: he invites the writer to negotiate the session agenda. Unlike tutors in many centers, though, this tutor works in a center that uses the “read-ahead method” (Scrocco 14), in which writers submit written work prior to their appointments so tutors can read and plan an instructional approach. While reviewing writers’ drafts in advance may afford tutors and writers advantages, one key risk emerges: tutors who plan for consultations may assume a more dominant role in a context where writers expect authorial control. In this study, I ask: when using the read/plan-ahead method, how can tutors maximize the method’s instructional benefits and simultaneously involve writers in agenda setting?

To explore affordances and constraints of this model, I analyze thirteen tutor-supervisor planning conversations and tutors’ subsequent consultations. My analysis considers writing center administrators’ common concerns about the read/plan-ahead model, offers guidance for using this model prudently, and proposes avenues for future research. A brief survey of writing center administrators suggests that the read/plan-ahead model remains fairly uncommon in part because many administrators worry that tutors who use this tool might be more likely to control the consultation with their planned agendas instead of collaboratively building agendas with writers. My results suggest that while tutors who use the read/plan-ahead method do introduce their instructional plans during consultations, most of the tutors in this study also elicit and address writers’ agenda items; this finding should reassure writing center administrators that tutors who use the read/plan-ahead method typically still seek and cover writers’ concerns during consultations. My qualitative analysis points to some strategies administrators and tutors can employ when using the read/plan-ahead method in order to minimize the likelihood of tutors sidelining writers’ agendas. These approaches include preparing a limited list of higherorder concerns to consider during consultations and formulating a list of questions to ask writers to encourage their active involvement in consultations.

Historically, writing center scholarship has touted the importance of collaborative consultation agenda setting, in part because writers feel more satisfied with consultations that focus on their preferred agendas (Black 155; Mackiewicz and Thompson 60; Thompson et al. 82; Walker 72). Jointly constructed agendas afford writers ownership over their writing process and improve the likelihood that they will utilize tutor/teacher feedback during revision (Mackiewicz and Thompson 64; Thompson 417; Williams 185). Moreover, collaborative agenda setting enriches tutorwriter relationships (Black 21; Corbett 84) and keeps consultations on track (Newkirk 313; Severino 109). Shared agenda setting ideally ensures that consultations

consider key global writing issues and that writing tutors do not dominate consultations (Mackiewicz and Thompson 15; Nickel 145; Severino 109; Valentine 93).

Achieving a mutually accepted writing consultation agenda is sometimes presented as an uncomplicated collaborative endeavor (Harris 374; Macauley 3). Tutors have traditionally been discouraged from bringing concrete plans to their conferences (Harris 33-34) and encouraged to ask writers to identify their concerns (Caposella 11; Kent 152; (Newkirk 303; Thonus 111). Non-directive, “student- centered” approaches (Reigstad and McAndrew 36) avoid “impos[ing] our agenda onto a writer and their text” (Anglesey and McBride). Tutor- training manuals outline how tutors and writers can negotiate “mutually agreeable goal[s]” (Gillespie and Lerner 39) for consultations: ask writers open- ended questions (Gillespie and Lerner 28- 29; Ryan and Zimmerelli 16); build agendas around high - priority writing issues (Caposella 12- 13; Ryan and Zimmerelli 14); and do not “ presume… [to] understand better than the writer[s] what the session needs to be about” (Macauley 6). Warnings about tutors exercising undue control over session agendas have appeared in tutortraining guides for decades (Gillespie and Lerner 41-42).

Contrary to this advice, though, research suggests th at some writers need more direction during agenda setting (Thompson 418-419). Moreover, tutors and writers sometimes disagree on the appropriate degree of directiveness during sessions (Clark 44; Thonus 124). Cultural norms and perceptions of teacher/tutorstudent relationships inhibit some writers’ active participation in agenda setting (Ewert 2544; Lee 431; Weigle and Nelson 219). During agenda setting, some writers may interpret non-directive approaches as frustrating or directive approaches as disrespectful to their autonomy; either scenario can create negative perceptions that may influence writers’ satisfaction with consultations and their likelihood of using tutor feedback.

Undoubtedly, some writing center contexts create real challenges for negotiati ng well- prioritized, shared agendas. When students bring advanced writing from fields and genres unfamiliar to tutors, tutors may struggle to read student writing, identify key writing issues, and set shared agendas with writers (Scrocco 13). In such consultations, tutors may have trouble reading and evaluating writers’ texts during consultations and identifying high -priority writing issues (Scrocco 11). For example, Jo Mackiewicz’s research reveals that tutors who lacked content-area knowledge in engineering assumed too much control over consultation agendas (“The Effects” 317), focused on lower- order concerns,

and provided incorrect advice (319-320). Such tendencies contradict fundamental writing-center principles of placing writers’ concerns at the center of sessions and prioritizing global writing issues.

One emerging tool for navigating these challenges is the read/plan -ahead method: tutors read students’ writing in advance and develop well- prioritized, research -driven instructional plans (Scrocco 10). In centers where writers come from advanced, highly technical fields, bring genres unfamiliar to tutors, or possess diverse linguistic repertoires, the read/planahead method may represent a game -changing strategy for improving tutor feedback (Scrocco 17). Furthermore, tutors with specific identity traits and conditions, such as anxiety, learning differences, or neurological disorders (e.g., attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder), may benefit from the opportunity to prepare for consultations with writers who bring challenging texts and writing needs. Despite the potential benefits of the read/plan- ahead method, this practice may encourage tutors to promote their own agendas more ardently than they might if they had arrived at consultations without premeditated plans. And if writers “sense an undeclared agenda, they can feel manipulated” (Cogie 40), potentially leading them to feel disengaged or resistant to tutors’ advice.

To assess the current prevalence of the read/planahead tutoring method and administrators’ apprehensions about this practice, I emailed a short IRB-approved survey to the Wcenter listserv and contacts at the seventy writing centers in my original review of websites (Scrocco 11). My survey asked respondents the following:

• whether their centers use the read/plan-ahead method and under what circumstances

• whether respondents have concerns about the practice.

Findings of this brief survey show that among eighteen responses, 11.11% allow the read- ahead method for any writer, 27.78% allow the practice only under specific circumstances, and 61.11% do not allow the practice at all. Among centers that allow the practice for certain consultations, only graduate-level or post -doctoral writers, faculty, and students working on lengthy projects may submit work in advance.

This short survey suggests that the read/plan-ahead method remains limited by logistical constraints (e.g., extra time and pay for tutors) and pedagogical concerns. Some respondents fear that tutors who read student writing in advance may hijack consultation agendas. Others worry that the read/plan-ahead model positions tutors as expert instructors rather than peer collaborators. Still others believe this method inhibits tutor-writer dialogue, encourages tutors to be overly directive, places undue focus on editing, and limits the traditional practice of reading writers’ work aloud. Conversely, survey respondents who use the read/planahead method praise the practice for relieving tutor anxiety particularly in sessions with advanced writers and for helping tutors offer better feedback. My survey reveals some perceived concerns and benefits of the read/plan-ahead method and highlights the importance of collecting concrete data on the practice to identify evidence-based affordances and constraints.

To interrogate common views of the read/planahead method, this study examines the dynamics of tutor-supervisor planning conversations and subsequent tutor-writer consultations. I consider which factors in read/plan-ahead consultations appear to support or detract from writers’ agendas. This study examines thirteen tutors’ pre-consultation planning mee tings and subsequent consultations in a writing center that exclusively uses the read/plan-ahead method. I seek to answer these research questions:

• During read/plan-ahead consultations, to what extent do the agenda items tutors and supervisors plan align with agendas that are proposed and covered during consultations?

• What potential benefits and constraints emerge in read/plan-ahead consultations as tutors and writers negotiate and enact tutorial agendas?

In this exploratory, mixed-method study, I use quantitative tools to trace the correspondence between tutors’ pre-consultation plans, proposed agendas discussed with writers, and covered agendas addressed during consultations. To add context to these results, I qualitatively analyze tutor-writer exemplars from my data set to examine advantages and limitations of this tutoring method. Armed with evidence from read/planahead consultations, writing center professionals can consider and modify this practice to meet the needs of their center’s tutors and writers.

This study occurred at a private, doctoral-granting institution in 2017 when 56% of writers at this writing center were graduate-level or postgraduate writers. Writers were predominantly non-humanities, multilingual international students. Most tutors were graduate students, and all tutors completed a semesterlong tutor-training course taught by rhetoric and composition faculty. The tutor-training course covered writing-pedagogy scholarship and instructional methods aimed to assist research writers across disciplines e.g., common “novelty” moves in research-based introductions, genre moves in “IMRaD” papers, and the notion of “bottom line up front.” During the first few semesters of tutoring, tutors regularly participated in pre-consultation planning meetings with their supervisors; thereafter, tutors read and planned for consultations independently, only seeking supervisors’ advice when neede d.

Data collection occurred on three days one day at the end of spring semester and two days about one month apart during the subsequent fall semester. All scheduled tutors were invited to participate. Thirteen tutor-writer case s were included in this study. All tutors read student writing in advance and consulted with supervisors and the researcher, who previously codirected the center for one year five years earlier. 2 The university’s institutional review board approved the research, and all participants provided consent for their planning conversations, consultations, and electronic appointment data to be recorded. Recordings were transcribed using Deborah Tannen’s me thod.3

Analysis involved 1) labeling and categorizing writing issues identified in tutors’ pre-consultation planning conversations (planned agenda items); 2) labeling agenda-setting phases and writing issues proposed and covered during tutor-writer consultations; and 3) tracing the alignment of writing items across planned, proposed, and covered domains.

I analyzed tutor-supervisor planning conversation transcripts using Mackiewicz and Thompson’s notions of pedagogical topics and actions (28). I coded agendafocused independent clauses as planned topics (writing issues or concepts) or actions (concrete pedagogical

exercises, resources, or actions that apply writing topics). I then synthesized related topics and actions into broad categories of “writing items.” I created a master list of writing items (see Appendix A), which encompasses general writing issues and competencies (e.g., thesis, grammar, content development) and common sections of genres (e.g., discussion section, executive summary, literature review).

Next, I analyzed writer -tutor consultation transcripts. I identified agenda-setting exchanges in which tutors and writers propose writing topics or actions to address during consultations. Using Reinking’s “agenda-setting components” ( ix), Mackiewicz and Thompson’s “opening stage” (4) and “closing stage” (78), and Thonus’s “diagnosis period of a tutorial” (256), I defined agenda-setting phases as marked conversational exchange(s) in which tutors or writers propose to address writing questions, topics, or issues. I included direct agenda-setting turns (e.g., “What are your concerns?”) and indirect turns (“Do you have any other questions?”) throughout sessions.

I then labeled “proposed agenda items” and “covered agenda items” in consultations. Proposed topics and actions include the writing issues either interlocutor proposes and/or explicitly plans to discuss during consultations. Covered topics and actions include writing items writers and tutors give sustained attention during “teaching stage[s]” of consultations (Mackiewicz and Thompson 173), regardless of whether they explicitly proposed the topic or action during agenda setting. I define “sustained attention” as exchanges involving more than a few cursory conversational turns related to a writing item.

For my quantitative analysis, I consolidated lists of agenda topics and actions into “planned agenda items,” “proposed agenda items,” and “covered agenda items” and traced the extent to which tutors’ plans emerge during subsequent consultations. To ensure analytical accuracy, I independently coded my transcripts three separate times to generate lists of planned, proposed, and covered writing items for all tutor-writer cases. Then, I collaborated with an outside rater to refine my analysis.4 The outside rater and I first met to review and refine my master list of writing items and definitions. Next, we independently used the master list of writing items/definitions to analyze all transcripts and generate

lists of planned, proposed, and covered writing items for each tutor-writer case. We met to compare our lists, negotiate discrepancies, and achieve consensus in the final lists.

Once we established final lists of writing items for all case s, I created agenda-alignment tables that mapped the writing items across planned, proposed, and covered domains. I examined individual rows within tutors’ agenda-alignment tables and tallied correspondence between writing items. I counted the presence or absence of the same writing item across three domains of planning, proposing, and covering, and I generated the following agenda-alignment percentages :

• planned/proposed percentage: total number of agenda items tutors plan with supervisors divided by total number of agenda items tutors and writers propose to cover during agenda setting

• planned/covered percentage: total number of planned agenda items divided by total number of items covered during teaching/instructional stages of subsequent consultations

• proposed/covered percentage: total number of planned items divided by total number of covered items

• planned/proposed/covered percentage: total number of writing items appearing in all three domains divided by the total number of writing items for the entire tutor-writer case

To synthesize these alignment percentages, I counted the number of tutor-writer cases that fell into the 0-24% range, 25-49% range, 50-74% range, and 75-100% range for each combination. See table 1 for an example of full alignment across domains and table 2 for an example of no alignment across domains. Table 3 is an example of a consultation in which the tutor and writer propose and cover some of the tutor’s planned items; fail to propose and cover some planned items; and add some additional writing items not planned or proposed.

To avoid relying on reductive quantitative findings, I wrote qualitative descriptions of each tutor-writer case. These descriptions note the nature of the tutorsupervisor planning conversations, the global and local writing concerns addressed, and the dynamics of tutorsupervisor and tutor-writer interactions. I used the contexts of preparation chats and consultations to theorize explanations for the alignment across domains.

This section summarizes individual tutor-writer alignment statistics and alignment percentages of all tutor-writer cases.

Table 4 outlines the backgrounds of tutors and writers, requested feedback from writers’ intake forms, attached documents reviewed during session planning, and time spent on individual tutor-supervisor meetings and tutor-writer consultations. About half of the tutors in this study are first-semester tutors (7), and about half are second- (2) and third-semester (4) tutors. More tutors are graduate students (8) than undergraduates (5), and most come from English-related programs (9) rather than non-English programs (4). Most writers in these consultations are multilingual international students (10) rather than domestic students5 (3). About half of these consultations are first visits to the center (6), and about half are repeat visits (7). About half of the writers are undergraduates (7), and approximately half are graduate-student writers (6). All 13 writers attached written drafts, and 10 writers attached assignment rubrics to their intake forms for tutors to review. Tutors’ preparation/planning conversations with supervisors run an average of 4 minutes and 49.5 seconds, and tutorwriter consultations run an average of 49 minutes and 44.7 seconds.

Table 5 shows statistics for individual tutor-writer cases:

• number of writing items mentioned across planned, proposed, and covered domains;

• in parentheses, numbers of writing items for each tutor-writer case’s planned, proposed, and covered lists;

• alignment percentages across four combinations of domains:

o planned/proposed alignment

o planned/covered alignment

o proposed/covered alignment

o planned/proposed/covered alignment

Most tutors’ alignment percentages fall into the ranges of 25-49% or 50-74% alignment. For planned/proposed alignment, planned/covered alignment, and proposed/covered alignment, 2 tutorwriter cases fall below 25% alignment, and 2 tutor-writer cases exceed 74% alignment in any column. For alignment of writing items across all three domains, 5 tutor-writer cases fall below 25% alignment; 6 tutor-

writer cases fall into the 25-49% alignment range; and 2 tutor-writer cases fall into the 50-74% alignment range.

As table 6 and figure 2 illustrate, most tutor-writer cases fall into the 25-74% alignment ranges for all combinations of domains. For alignment between planned/proposed writing items, 7 tutor-writer cases fall into the 25-49% alignment range, 5 cases fall into the 50-74% range, and 1 case falls into the 74-100% range. For alignment between planned/covered writing items, 6 tutor-writer cases fall into the 25-49% alignment range, and 6 cases fall into the 50-74% range. For alignment between proposed/covered writing items, 2 tutor-writer cases fall into the 0-24% alignment range, 5 cases fall into the 25-49% range, and 6 cases fall into the 50-74% range. For alignment across all three domains (planned, proposed, and covered), most tutor-writer cases fall into the 0-49% alignment range: 5 cases fall into the 0-24% range, 6 cases fall into the 25-49%, and 2 cases fall into the 50-74% range.

Table 7 displays measures of central tendency across all 13 tutor-writer cases, demonstrating the mean, median, mode, and range of the following: total number of writing items mentioned across the three domains, and alignment percentages between planned and proposed writing items, planned and covered writing items, proposed and covered writing items, and across all three domains. An average of 12 writing items emerges per tutor-writer case across planning conversations and consultations. Tutors plan an average of 7.6 writing items, propose 5.8 items, and cover 10.9 items. An average of 50.97% of writing items tutors plan ultimately emerges as proposed agenda items during consultations. An average of 52.88% of writing items tutors plan with supervisors receives coverage during consultations. An average of 45.09% of writing items tutors and writers propose during agenda-setting phases of consultations receives coverage during teaching phases of consultations. As for alignment percentages across all three domains, approximately one-third (33.84%) of writing items tutors plan to address emerges in both proposed and covered domains during consultations.

This section adds texture to my quantitative results by qualitatively analyzing three tutor-writer cases. These cases reflect quantitative results slightly above or below this study’s averages (see tables 5 and 7). I aim to analyze some scenarios that unfold when tutors use the read/plan-ahead method, and I highlight both missteps

and strategic use of this practice. The first exemplar, the Tutor 7- Writer 7 case (see table 8), characterizes a planning conversation in which the tutor and supervisor engage in detailed planning much of which the tutor covers during the consultation. The second example, the Tutor 4-Writer 4 case (table 9), examines a planning meeting in which the tutor and supervisor prepare vaguer plans, and the ensuing consultation seems unfocused. The third exemplar, the Tutor 1-Writer 1 case (table 10), illustrates a tutor who appears to balance pre-consultation plans and the writer’s concerns, establishing and covering a well -prioritized, shared agenda.

In this study, very detailed pre-consultation planning particularly with inexperien ced tutors appears to contribute to tutors taking more control over their consultations. One quantitative clue to this scenario is a higher-than -average planned/covered alignment percentage. For instance, Tutor 7, a firstsemester tutor, makes specific, co mprehensive plans with a supervisor and later directs most agenda-setting and instructional phases of his session, repeatedly relegating the writer’s concerns to a lesser status than his plans. During teaching phases of the consultation, the tutor does not deviate much from his instructional plan, and he redirects or only briefly addresses the writer’s proposed agenda items. In this case, roughly two-thirds of the tutor’s planned agenda items receive coverage during the instructional phase of the consultation (higher than the average of about half).

Tutor 7 engages in a longer- than- average preparation conversation that produces a detailed consultation plan a total of eight specific writing issues. First, he mentions that the writer’s main concern on the intake form is the grammar in his reading response document. Disagreeing with this priority, the tutor tells his supervisor, “The main thing I need to focus on here is, um, like, the rhetorical situation.” With the advisor, Tutor 7 highlights the writer’s key problem a failure to answer the prompt. They discuss concrete options for supporting the writer’s revision process, such as using the center’s “bottom -line -upfront” handout to explain how to foreground claims in a thesis and topic sentences. They also discuss how generating a reverse outline might address the draft’s organizational problems.

Entering the consultation equipped with a comprehensive plan and presuming that the writer lacks awareness of his writing issues, Tutor 7 directs or redirects most agenda-setting and instructional phases

of the consultation. The writer, a multilingual international graduate student with prior experience at the center, presents some agenda items but largely defers to the tutor. Marking the first agenda- setting phase, for instance, the tutor begins by introducing his planned areas of concern. When the writer interrupts to articulate his interest in discussing content development and grammar, the tutor explicitly opposes these proposed agenda items, redirecting the focus: “Uh, so, I would actually say, rather than adding more points, I think you have a lot of points here, and, like, a lot of good information. Uh, what I think is more important is to, kind of, like, reorganize them in, in, like, like, based on what the prompt is asking.” The writer responds with a brief, “Ok,” followed by the tutor asking about the context of the assignment.

Soon after, mirroring his supervisor’s advice to focus on structure, Tutor 7 proposes discussing the “bottom -line -up -front” notion and handout. He asserts, “Uh, I think, the thing that could, like, help your essay the most, um… is the idea of, um, bottom line up front… um, where we have one of our handouts that we love to use, um ” As Tutor 7 explains the benefit of placing key ideas in primary positions in the text, Writer 7 mainly provides brief backchannel. He interjects at one point to inquire again about adding details: “They’re asking about a minimum seven hundred words, so, I don’t know if I sho uld add more, or just keep I don’t know.” Maintaining control over the agenda, the tutor reassures the writer that they will likely add content while rearranging paragraphs. He resumes discussing structure, reinforcing his planned agenda: “I say, I say let’s start by reorganizing the paragraphs, and I bet you’ll find that, like, once you do that, then you, you’ll find there’s, like, more you can say about it.” Again, dismissing the writer’s proposed agenda items, Tutor 7 positions the writer as a novice whose articulated concerns hold lesser value.

Later, the tutor takes the lead once more by proposing another pre-planned agenda item:

So, so, now, I think, the best way to go, is to, kind of, like um, and, and, like, once again, uh, feel free to stop me if you’d rather do something else […] you, kind of, have these ideas… And, now, you want to create paragraphs that will, like, support these ideas, and, like, kind of, go into more detail.

While the tutor offers a perfunctory opening for the writer’s agenda here, Writer 7 passively accepts the tutor’s recommended course of action. In a similar way, later, Tutor 7 returns to another planned agenda item,

directing the next activity: “So, I’m thinking, kind of, leave these paragraphs, but, like, also, we’ll work on putting topic sentences for them,” with the rationale that “now I understand what you’re doing with these paragraphs, it was, kind of, hard to tell at the time because of the lack of topic sentences.” The writer again accepts the shift in the consultation focus without objection, and they begin developing topic sentences.

With just a few minutes remaining, Tutor 7 returns to the writer’s primary concern from the intake form one the writer reiterated early in the consultation. The tutor asks, “Do you want to spend some time I mean, we have, like, six or seven minutes left. Do you want to spend some time talking about grammar a little bit?” Finally giving credence to the writer’s main concern, the tutor offers to address grammar for a few minutes. After identifying and correcting various surface-level errors, though, he admits that his grammatical instruction amounts to mere editing, and he suggests that they move on. The writer agrees, stating that generating ideas has been useful.

Overall, this tutor appears committed to executing his initial plan for the consultation, perhaps because he lacks tutoring experience and views the detailed plan he developed with his supervisor as an unalterable consultation blueprint. Problematically, he assumes that the writer is unaware of his writing problems, and he directs most of the agenda and teaching phases instead of prioritizing the writer’s concerns.

Unlike very detailed pre-consultation planning, when tutors and supervisors and/or tutors and writers sketch very general or vague plans, the results are higher-than-average proposed/covered alignment percentages; these sessions tend to be more reactiondriven consultations. For instance, Tutor 4 develops a broad plan for the consultation with his supervisor with a total of five general writing items (fewer than the average). During this consultation, the tutor and writer do not engage in substantive agenda setting; instead, they spontaneously propose agenda items throughout the appointment and address those items as they arise. This approach, while strongly aligning proposed and covered agenda items, undermines the goal of building a cohesive, well-prioritized session that balances tutor, supervisor, and writer concerns. In this way, this consultation lacks the key benefit of reading and planning ahead: carefully considering complementary topics and actions that writers might most benefit from addressing. Less-developed planning and consultation agenda negotiation may create a reactive tutoring session

that presents disconnected impressions of the text rather than an organized, well-prioritized, memorable consultation.

In his planning meeting, Tutor 4, an undergraduate tutor concluding his first year of tutoring, and the supervisor discuss the writer’s research paper. Evaluating the paper as “pretty close” to completion, the tutor points out a missing connection between the writer’s “overarching theme” and conclusion. He highlights the rubric’s requirement that the paper articulate a novel claim, and he assesses the argument as an unelaborated, “kind of, like, a standard, um kind of, opinion.” The tutor proposes addressing one broad writing issue: clarifying the novelty of the writer’s main argument by distinguishing it from secondary-source claims. They do not discuss concrete actions or resources to utilize during the appointment.

The ensuing consultation reflects the vagueness of this pre-consultation meeting. The tutor opens the consultation with the writer, a repeat visitor to the center who is an international undergraduate in her first year, by eliciting her concerns: “Um, real quickly before we get started, um, I had a couple of things that I wanted to go over with you, but I wanted to ask, in terms of setting an agenda, um, did you have anything in mind, like, specifically, you wanted to go over in the paper, or, like, a specific section?” Couching the invitation to shape the agenda in his own pre-determined instructional plan, the tutor limits the writer’s contribution to the agenda by asking her which section she wants to review. The writer points to the section of the paper that most concerns her, and the tutor agrees without clarifying what writing issues require attention: “Um, so, you just wanted to go over that, and see if that, kind of, flows, and your argument’s clear...” His follow-up question, “Just, kind of, general quality?” launches a broad, poorly defined agenda that parallels the unclear plan generated with his supervisor.

This incomplete agenda-setting stage prompts a conversation that primarily alternates between the writer’s descriptions of her intentions and the tutor’s reactions to the paper. Rather than a rich, dialogic interplay centered on related global writing issues, each interlocutor takes extended conversational turns, explaining their perspectives on the paper’s claims before asking the interlocutor a broad question. For instance, after a protracted commentary on the writer’s argument, Tutor 4 asks a general question: “Ok, so first paragraph: what do you think?” The writer replies to this broad question with a lengthy explanation of her paragraph’s goals, which the tutor accepts with backchannel before engaging in his own extended

explanation of his confusion. He then proposes another vague agenda item discussed with his advisor: “Um… so, what I would suggest is we can try to work on, kind of, expanding this connection in this last paragraph.” The writer passively accepts this recommendation, and they resume their pattern of alternating lengthy conversational turns that analyze the overall argument.

About halfway through the consultation, Tutor 4 presents the writer with several options for what to discuss next. The writer responds in general terms: “Um, I also wanted to go over previous… sections.” The tutor does not ask her to specify which sections or writing issues she wants to consider; instead he refers to the abstract and introduction sections. They resume alternating between extended conversational turns, offering disconnected impressions, ideas, and suggestions for the paper.

My analysis of the Tutor 4-Writer 4 consultation suggests that during read/plan-ahead consultations, a vaguely planned agenda paired with a poorly negotiated agenda may lead to a reaction-driven consultation. An undeveloped plan may reflect the tutor’s uncertainty about appropriate instructional topics and techniques. Such ambiguity might signal the tutor’s need for more specific direction and guidance from a supervisor or colleague. In this case, a vague tutor-supervisor plan combines with an unfocused tutor -writer agenda to set up a disorganized, disjointed consultation. This consultation broadly addresses various writing issues thesis, introduction, content development, organization, and bottom-line -up-front but the absence of meaningful back-and-forth dialogue between the interlocutors implies a lack of cohesion and comprehensibility that may inhibit the writer’s revision or growth.

In the most qualitatively effective consultations in my study, tutors develop short but precise lists of writing items with supervisors and, later, elicit and incorporate into the agenda several of the writers’ concerns. These tutors demonstrate how the read/planahead model might be used constructively to prepare tutors for consultations without undermining the writing-center ideal of establishing shared agendas. For example, Tutor 1, a first-semester tutor in the literature MA program with three years of high-school teaching experience, consults with Writer 1, a multilingual international graduate student in his first visit to the center. In the consultation, they establish alignment percentages that fall slightly below the averages in this

study, indicating the tutor’s responsiveness to the writer’s agenda.

In a longer-than-average pre-consultation conversation, the tutor, supervisor, and researcher generate a list of five specific writing items to address. They first speculate about whether the writer understands the purpose and trajectory of his literature review. The tutor plans to prompt the writer to explain the “main news” of each literature-review subsection. They also discuss missing and unclear research-novelty moves. Identifying concrete supporting resources, the tutor mentions the center’s literature -review handout with examples showing how literature reviews craft arguments. This planning conversation robustly analyzes the writer’s text, and the tutor proactively strategizes specific writing topics and corresponding instructional actions.

Although the tutor enters the consultation with a concrete plan, he begins by meaningfully soliciting the writer’s concerns: “So, I think, the first thing we should do is set an agenda about what we want to talk about today. So, were there any, uh, questions, comments, issues, uh, that you wanted to look at in this literature review?” In response, the writer proposes that they discuss whether his literature review includes sufficient content and organizes ideas appropriately. Listening attentively, Tutor 1 agrees with these writing areas, adding one of his own planned items: discussing the key claim the audience should understand. This early agenda-setting discussion maintains equilibrium between the tutor’s plan and the writer’s expectations for the session a balance the tutor continues as the consultation progresses.

Later, echoing a concept discussed during his planning meeting, the tutor connects his own and the writer’s agendas with a specific, guided question: “So, is the literature review what, what is the purpose of the literature review in, kind of, the larger project for you?” The writer begins explaining the project’s main foci, prompting the tutor to address the document’s subheadings and his previously articulated concern about the literature review’s structure. Tutor 1 explains, “The reason I’m doing this is so that, you know, because you wanted to talk about structure, and I agree that’s definitely something very important. So, I definitely wanted to figure out, kind of, what the, the main ideas you’re communicating [are].” Harkening back to the writer’s concern about the paper’s organization reveals the tutor’s commitment to addressing the writer’s proposed agenda an act that links the tutor’s plan with the writer’s concerns. This apparently intentional effort to reconcile his own and the writer’s priorities shows

that tutors who plan ahead can still place writers at the center of consultations; they can make productive, meaningful associations between supervisor, tutor, and writer concerns.

Again linking his plans with the writer’s concerns, the tutor then presents a new direction for the second half of the appointment: “So, um, what I want to do for the next, I guess, twenty-five minutes is, um, talk about maybe how we can structure this so that it’s more of, it’s more of an argument, um… What, what do you know about literature reviews? What experience do you have about literature reviews? Have you written any before?” Here, Tutor 1 segues from the writer’s interest in structure into his plan to discuss how literature reviews craft arguments. The tutor’s open-ended, guided questions encourage the writer to articulate his understanding of a literature review and reveal areas of confusion. As the writer answers these questions, Tutor 1 broaches an instructional action discussed with his advisor reviewing the literature -review handout. A logical outgrowth of their conversation about the genre’s structure, the tutor shows a literature-review example, and they collaboratively mark similar rhetorical moves in the writer’s draft.

The case of Tutor 1 reveals how tutors who read and plan ahead can balance their instructional plans with writers’ concerns by beginning with dedicated agendasetting exchanges and drawing on but not pushing their own planned agendas. Tutor 1 takes advantage of the read/plan-ahead model, preparing focused, researchbased plans with a knowledgeable supervisor but he does not follow that agenda strictly. Instead, he elicits the writer’s concerns and draws explicit connections between his own plans and the writer’s agenda. After a rich, dialogic consultation, one might expect the writer to retain both the tutor’s advice and his ownership over the text.

This exploratory, mixed-methods study considers how the read/plan-ahead method may be used in writing centers. Although limited to thirteen tutor-writer cases with undergraduate and graduate tutors in their first three semesters of tutoring, this study offers a glimpse into the affordances and constraints of this emerging practice. Unsurprisingly, all thirteen tutors introduce some of their planned instructional topics and actions into their consultations; this finding demonstrates that tutors who plan for sessions with more-experienced supervisors carry some of those plans into their consultations. Thus, the read/plan-ahead model achieves its intended goal of allowing tutors to

strategize some direction for their consultations. In sessions with advanced writers from unfamiliar fields, many tutors would welcome pre-consultation planning and guidance from more-experienced supervisors and colleagues.

Nonetheless, only about half of the writing items tutors and supervisors plan to for consultations arise during tutor-writer agenda setting, and only about half of planned items receive coverage during instructional phases of consultations. Moreover, roughly one-third of writing items appear across tutors’ planned, proposed, and covered domains, suggesting that these tutors do request and prioritize writers’ agenda items, abandon their plans when writers resist their agendas, and address new writing items as consultations progress. Tutors who use the read/plan-ahead method do not appear to fervently push their planned agendas once they enter writing consultations. These quantitative results might reassure writing center administrators who are hesitant about this tutoring model: tutors who prepare for consultations do not ignore or disregard writers’ agendas and priorities. Indeed, tutors who plan for consultations can engage in the “active listening” Anglesey and McBride and others advocate and can remain collaborative peers rather than directive instructors.

While my quantitative findings suggest most tutors in this study balance planned, proposed, and covered agendas, my qualitative findings complicate these results. My qualitative analyses reveal differing degrees of receptiveness to writers’ agendas and varying abilities to address coherent agendas. In this portion of my analysis, we observe how one tutor whose alignment percentages fall slightly below the study’s alignment averages exhibits skill in connecting his planned agenda with the writer’s concerns. We also observe a tutor whose planning conversation addresses broad writing issues as he ultimately engages in a reaction-driven consultation, and we see how a less-experienced tutor who engages in quite detailed planning pushes his plans over the writer’s concerns. These cases reinforce the importance of limiting the number of planned writing topics and actions to avoid placing too much pressure on tutors to cover a long list of specific writing issues. In addition, these cases point to the significance of regularly observing tutors as they use the read/planahead method; such observations should ascertain how tutors manage conflict between their planned agendas and writers’ articulated concerns. Conducting consultation observations and meeting with tutors afterward to analyze observation notes may enable

administrators to pinpoint examples of successful and ineffective uses of this practice.

Ultimately, the question of why some tutors enact their plans more stringently than others remains unanswered. Without systematically analyzing a larger sample of planning meetings and consultations and interviewing tutors about their intentions, one cannot definitively state what factors influence the degree of correspondence between tutor’s plans and proposed and covered items in their consultations. Determining factors may include the nature of pre-consultation meetings, consultation contexts and dynamics, and tutor and writer experience levels and traits. Regardless of what affects alignment across domains, decades of writing center scholarship on the pedagogical value of tutors and writers collaboratively building consultation agendas suggest that tutors who use the re ad/planahead method should never strictly enact their preplanned agendas at the expense of writers ’ concerns. Instead, based on the results of this exploratory study and my firsthand experience working in a center that uses the read/plan-ahead method, I propose that tutors should use this method to formulate tentative instructional plans and then, present those plans to writers for collaborative modification. Although students come to writing centers pursuing writing advice, they simultaneously seek and deserve to exercise autonomy in their writing process. The read/plan-ahead model does not inevitably threaten this ideal; if tutors’ preparation sessions begin with the concerns writers list on their intake forms and formulate tentative agendas that complement writers’ concerns, the read/plan-ahead method can reinforce the traditional principle of placing writers at the center of consultations.

Because tutoring is a complex endeavor, no universal degree of alignment exists across planned, proposed, and covered domains in read/plan-ahead consultations. Tutors and writers address and ignore instructional topics and actions for various reasons either deliberately or inadvertently. Tutors may plan to discuss specific topics and corresponding actions, but once they begin negotiating agendas with writers, they may decide to give other topics and actions precedence. In other cases, tutors may intentionally abandon planned agenda items, forget to suggest and address planned items, or reject planned items when writers challenge them. Tutors and writers may also agree to cover certain topics or actions but find they lack time to address the items during teaching phases of their consultations. In short, tutors and supervisors should not expect or strive for total alignment across all three domains of planned, proposed, and covered agendas.

Instead, the goal should be approximate correspondence between high-priority topics and actions that tutors plan, negotiate with writers, and attend to during consultations. Ultimately, administrators and tutors should always remember the philosophy underpinning the read/plan-ahead method: tutors can more effectively guide consultations (especially with advanced writers from unfamiliar fields) if they carefully prepare cohesive agendas and then present those plans to writers for revision.

While this study of the read/plan-ahead tutoring method remains limited by the number of tutor-writer cases and the context of this writing center, its conclusions offer some direction for administrators. One takeaway is that planning too much or too little may set tutors up for consultations that fail to negotiate and carry out well-prioritized, mutually accepted agendas. Planning lengthy, detailed lists of concrete agenda items might place undue pressure on tutors to accomplish too much during consultations and could lead tutors to push their planned agendas over writers’ concerns. On the other hand, vaguely planned agendas may provide insufficient guidance for tutors especially inexperienced tutors or tutors working with advanced writers from unfamiliar disciplines; ambiguous plans may lead to disorganized, reaction-driven consultations.

Future research on the read/plan-ahead model should examine some common concerns articulated by my survey respondents about this practice. One frequently mentioned fear about this emerging model from my survey is that reading and planning in advance stifles peer dialogue a main benefit of writing center consultations. A related concern is that tutors who read ahead might focus disproportionately on lower-order concerns or editing. Studies comparing read/plan-ahead consultations with traditional consultations might examine some of these apprehensions. For instance, a study might compare whether tutors in read/plan-ahead consultations talk more often or more authoritatively than tutors in traditional consultations. Another study could examine whether tutors who read and plan ahead focus more of their sessions on editing than tutors in traditional sessions. Some survey respondents also worry that tutors who use the read/plan-ahead method may enter consultations in a hierarchically different position than tutors who read student writing during consultations; a similar concern is that writers may expect tutors who read and plan ahead to act as teachers who guarantee “perfect” writing. To test these assumptions, surveys or interviews with writers

participating in both read/plan- ahead and traditional consultations could compare writers’ perceptions of tutors’ roles and their expectations of what tutors should provide during consultations.

Another avenue for future research might consider the role of tutor identity in read/plan- ahead consultations. One unanswered question from this study is whether certain tutors might benefit more from the read/plan -ahead method than others; for instance, tutors who suffer from anxiety or have specific learning differences or neurological conditions might benefit from using this tool more than tutors without these traits. Because this study did not collect data on participating tutors’ traits and neurological conditions, one can only speculate about whether the efficacy of this tutoring method depends on tutors’ identity. Future research on the read/plan -ahead method might more fully account for the role of tutor identity in these types of consultations For example, a survey study could examine whether tutors with specific traits or conditions express higher levels of preference for the read/planahead method than tutors without the same traits or conditions. To examine whether tutor identity influences the efficacy of the read/plan- ahead method, an observational study could collect data on tutors’ traits and conditions, record the tutors in traditional consultations and in read/plan -ahead consultations, and compare the consultations in terms of tutors’ reported levels of anxiety or stress, tutors’ and writers’ satisfaction with consultations, and other metrics that determine the success of tutoring sessions.

In the absence of evidence on these matters, administrators may confront common concerns about th e read/plan - ahead model in tutor professional development. Administrators should emphasize that consultation preparation should always start with writers’ listed concerns on intake forms, and consultations must always begin by eliciting and prioritizing writers’ concerns. Tutors might practice strategies for explicitly connecting their plans with writers’ concerns. They might role play common agenda-negotiation scenarios and rehearse how to manage tension between tutors’ and writers’ agendas. While the read/plan -ahead method does not require experienced tutors to meet with supervisors to plan for consultations, supervisors should regularly observe their tutors’ read/plan -ahead consultations, note how tutors balance and connect their plans with writers’ agen das, and discuss with tutors how to navigate agenda- based conflicts.

Administrators can use the read/plan - ahead model and maintain a culture of collaboration and peer

dialogue in their center. Center websites and outreach materials should clarify that although tutors prepare for consultations, writers’ priorities always take precedence, and tutor-writer conversation remains central to all consultations. Administrators should clarify how much of a writer’s text can typically be covered during appointments and should explain what types of writing issues tutors prioritize higher -order global concerns. Outreach materials should also articulate that tutoring always aims to support writers’ processes, not create perfect documents.