2023, Issue 1

1 Art Matters

1 Toledo Museum of Art

Experience 02 From the Director’s Desk Looking back to understand what’s ahead with Adam Levine, the Edward Drummond and Florence Scott Libbey Director and CEO 30 Store Feature Craig Fisher’s works use the techniques of the past to create complex contemporary works 28 On View & Upcoming Explore this season’s slate of exciting and engaging exhibitions 32 TMA Glass Studio Hits the Road TMA glass studio artists embark on community outreach with their mobile hot shop 18 A New Space for Community Celebrating Bob and Sue Savage’s support for showcasing the work of regional artists 20 A Grand Affair The history Museum soirees, from opening day to the 2020s 24 A Dawn Omen: Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg A UK artist makes her US debut with Machine Auguries: Toledo 06 Inside the Issue Who decides which narratives we retell and which we leave behind? 08 Expanding Horizons: The Roundtable Discussing the new vision for TMA’s American art collection 12 In the Studio: Beth Lipman Our recent GAPP resident reexamines Florence Scott Libbey’s role as museum co-founder

Think Discover

Over the past year, one of the questions I am most frequently asked is: “What do you think of the phenomenon of van Gogh experiences?” Cities across the world have hosted immersive exhibitions that feature largescale digital animations of Vincent van Gogh’s artwork projected on walls and set to music and narration. These experiences are “spectacular,” literally and figuratively—they are visually striking, but they also subordinate van Gogh the artist to van Gogh the brand.

While they are not art, per se, they are more interesting than I expected and are fun escapes for millions of people. However, the vastly more interesting thing that these experiences represent

is that certain technologies (like projection mapping) are now so broadly available that artists can begin to use them. Imagine using cutting-edge technology like what you see in van Gogh experiences to create bona fide art; the results would be powerful.

I appreciate that this idea of artists using futuristic technology may sound fanciful, but across time and history, it is almost always artists who adopt new technologies the quickest. Consider as an early example the Museum’s magnificent Bust of a Flavian Matron (2016.19), purchased by the Georgia Welles Apollo Society. Now on view in Classic Court, the late 1st Century sculpture depicts a woman with ornate corkscrew curls, characteristic of the Flavian

Dynasty (69-96 C.E.). The deep holes carved into her coiffure were created by the running drill, a technology that had existed since the 4th century BCE but that was refined 500 years later, enabling the creation of the deep holes and grooves that punctuate our matron’s hair.

If we fast forward nearly two millennia, Nam June Paik’s Beuys Voice (2015.16) serves as another case of artistic innovation with technology. Nowadays, you can walk into any sports bar (as many are during this season of March Madness) and see multiple televisions networked together to show a contiguous image of a sporting event; Nam June Paik was among the first people to achieve this technical feat. Here, the artist

the Director’s Desk

2 Art Matters / INTRODUCTION

FromBust of a Flavian Woman c. 90 CE. Marble. H: 20 in. Gift of The Georgia Welles Apollo Society, 2016.19

who invented the term “information superhighway” creates a humanoid sculpture (what he called a “robot”) out of two channel color televisions. Paik foresaw the dominance of the screen in contemporary life, creating works of televisions matrixed together as early as the 1970s (TMA’s sculpture dates to 1990).

These are but two examples that demonstrate artists are the early adopters of new ideas, new techniques, and new technologies across time, place, and culture. Sometimes, in order to understand where things are going, one has to look backwards. Among the special attributes of an art museum is its ability to give that historical perspective, so it should come as no surprise that this idea—that our future is reflected in our past—runs

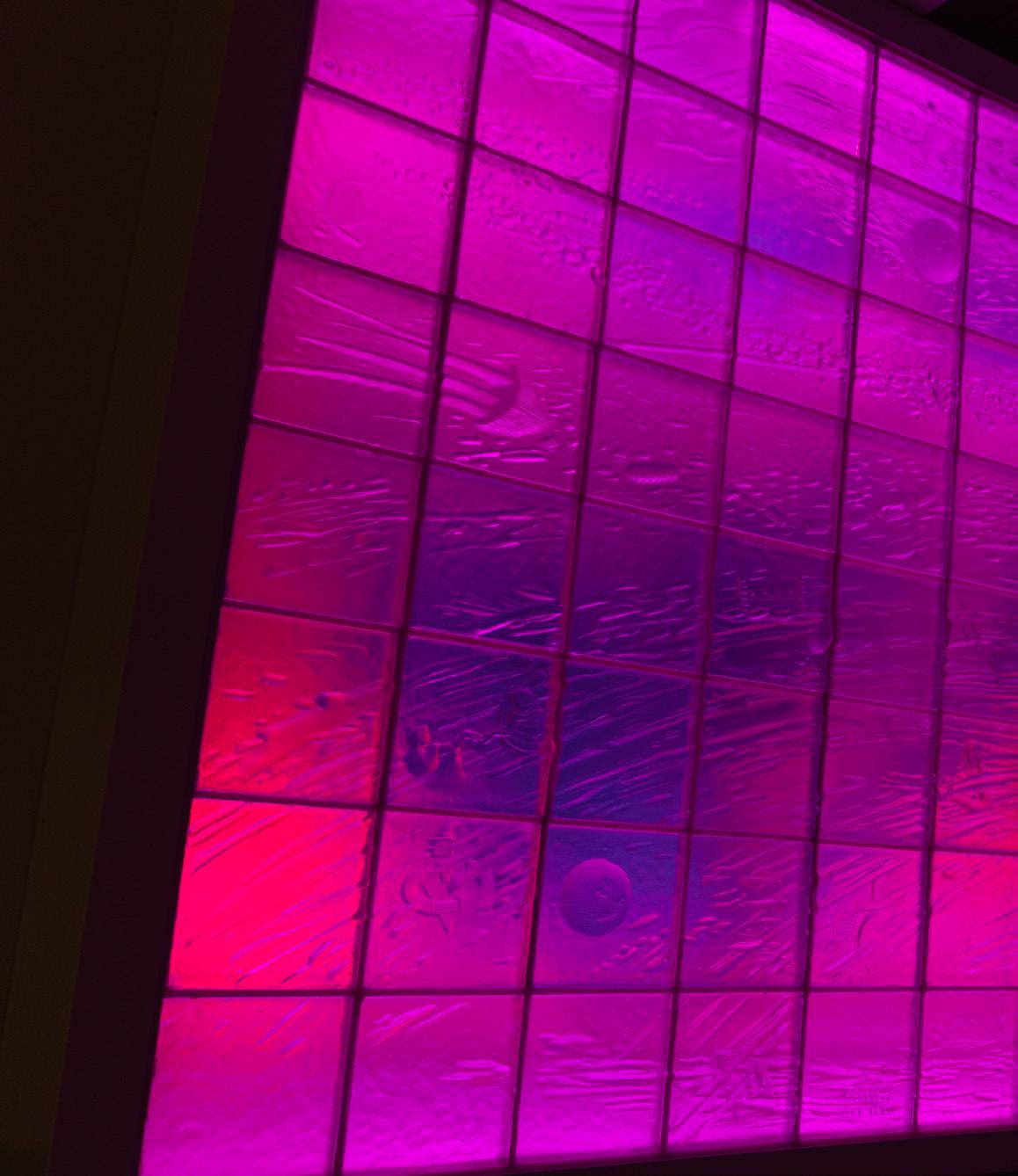

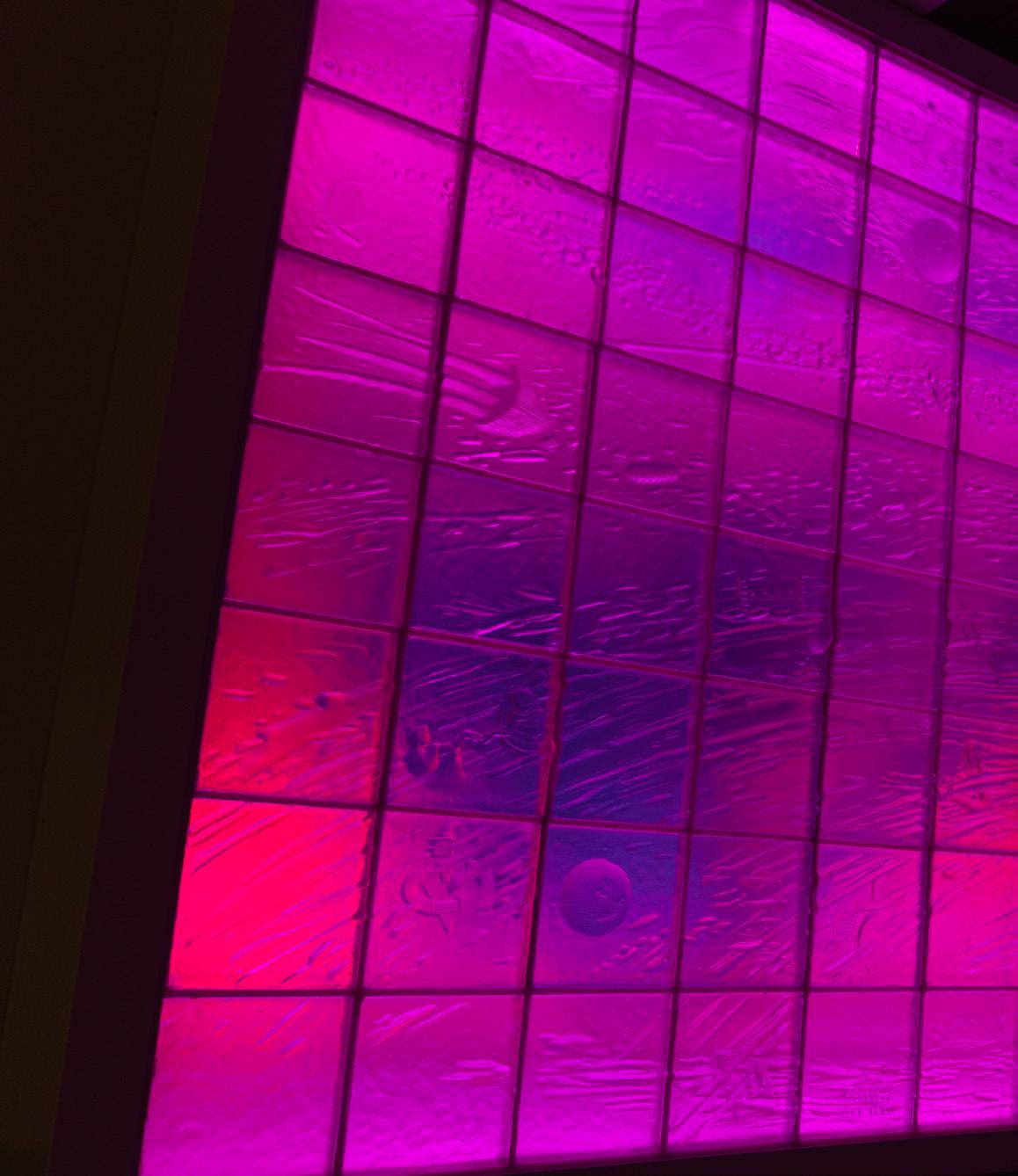

Machine Auguries: Toledo—an immersive installation that uses artificial intelligence as its medium. The artist, in collaboration with the Macaulay Library at Cornell University and local volunteers from organizations including the Black Swamp Bird Observatory, have used a method of machine learning called a generative adversarial network (GAN) to “train” a computer to forecast how bird calls change as a result of modifications to their natural environment (some brought on by human habitation and economic development). Using local bird call data, Machine Auguries creates an immersive installation that will cause visitors to experience how bird calls are changing in our region and what they might sound like in the future. This profound work of art, which opens April 29 in conjunction with the Biggest Week in American Birding, will be unlike anything this community has ever seen.

Character of a Nation on March 18. The refreshed installation of our American art collection in the New Media Galleries continues our effort to tell broader, truer, and more inclusive stories by situating history in a global network rather than in geographic silos. By looking at the ways that North and South America—and the United States of America within those boundaries— has developed, this path-breaking installation will help us get a better sense of where we are headed.

Two other features in this issue— one on the history of special events at TMA and one on the relaunch of a community gallery, generously funded by Bob and Sue Savage— also give a sense of how the Museum’s approach to engaging the Toledo area continues and updates longstanding traditions and approaches.

through this issue of Art Matters.

Perhaps the most literal example of “learning from the past” at TMA this spring, and the example that demonstrates what the adoption of new technology looks like in 2023, is the United States debut of artist Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg’s

Machine Auguries is not the only gallery-sized installation at TMA this year. Leading contemporary artist Beth Lipman has spent weeks in Toledo through our Guest Artist Pavilion Project (GAPP) residency, generously endowed by Sara Jane DeHoff, to recreate Florence Scott Libbey’s library using glass made in TMA’s hot shop. This not-tobe-missed installation, opening in Gallery 18 in August, centers Florence Scott Libbey not just as a great benefactor but as a breathing force inspiring the art of today.

Erin Corrales-Diaz, TMA’s first dedicated curator of American Art in nearly five decades, opens Expanding Horizons: The Evolving

In the foregoing examples, you can see one of the hallmarks of our current approach: Rather than departing from historical norms, we seek to update them for the 21st century. TMA, like each of us, like our country, and like artwork itself, evolves over time. It is a great joy to continue that tradition of evolving, stewarding the history of human creativity and framing the ways we look backwards so we can look forward to an ever-brighter future.

Thank you for your support, which makes this possible.

Sincerely,

Adam Levine

3 Toledo Museum of Art

Director’s Desk

4 Art Matters / THINK Think

John Burroughs

Cartaino di Sciarrino Pietro (American, 1886-1918) 1918. Bronze. 47 × 54 1/4 × 32 in.

Gift of William E. Bock, 1918.2

5 Toledo

of Art

Museum

Think

6 Art Matters / THINK A

3

visitor explores Gallery

during 2022’s Great Art Escape.

Photo: Ben Morales

Inside the Issue

Who Decides the Narratives?

One could call it a law of nature: a story multiplies.

Like a drop descending into a petri dish, once it separates from its author a story gets busy making more of itself, taking on new shapes, becoming plural and nebulously shaped things, forms whose boundaries are sometimes a distant echo of the lines that were first laid.

A story isn’t singular, and neither are the complicated people that make up its audience. As Walt Whitman famously wrote, I contain multitudes. Our narratives do, too.

The mechanisms that drive this multiplication from story to stories are many. Historians, for one, try their hand at making sense of the forms. Politicians attempt to redraw the lines themselves. Artists, aiming to interpret and build upon the past, seek new ways to define what counts for a shape. Even we play a powerful role, as listeners and re-tellers. Understanding that there is

more than one story unlocks a relationship with the past that is alive. In this living exchange, past, present, and future remain in conversation—dynamic, changing, evolving. As knowledge and perspective grow, so do the stories.

That is the only call to action, if it can be called one, for this spring and summer’s art experiences at TMA: to reconsider. Who crafted our stories, and why—and which will we choose to inherit, to pass on, to make our own in the retelling? This question is more relevant than it may seem at first blush, for the artists tasked with asking it, but also for you, the audience.

Arming ourselves with this knowledge creates a novel way to experience art. At first it might feel like an unmooring of sorts. Where there were authoritative statements, there are now open-ended questions and the opportunity to ask them. There’s far less telling than there used to be, and while it can be uncomfortable, even prickly, it also holds the

potential glow of discovery.

With that comes an invitation to share your feedback, comments and insights about how the art in the Museum is displayed in its galleries. It will give curators— historically the authority in this area—a renewed relationship with you, the audience, one that encourages dialogue as TMA embarks on the years-long project of reinstalling its collection with an eye for fresher, truer storytelling. The first iteration of that discussion, the American art installation Expanding Horizons: The Evolving Character of a Nation, includes in its title the essential concept at the core of these exchanges and learnings: evolution.

Like the United States of America, this institution is also ever-evolving. It is growing to be a clearer mirror for the community that surrounds it, one that understands there is never only one story—and that our world is richer when we make space for more of them.

7 Toledo Museum of Art

Expanding Horizons: The Roundtable

Exploring an Expansive and Ambitious Vision for Art in the Americas

Panelists

Erin Corrales-Diaz

Curator of American Art

Paula Reich Manager of Gallery Interpretation and Learning

Andrea Gardner Senior Director of Collections and Curatorial Affairs

The reinstallation of American art in TMA’s galleries—titled Expanding Horizons: The Evolving Character of a Nation—brings with it many novelties. It invites new stories, as viewers discover new aspects of works they know and love, as well as a new role for audience members, as they are asked to actively participate by providing their feedback, which the Museum hopes to implement in future iterations. We sat down with three members of the large team working behind the scenes on this project to discover their goals for designing a more thoughtprovoking, participatory experience.

8 Art Matters / THINK

Art Matters: There are two facets to the title of this new installation, and they seem equally meaningful— both Expanding Horizons and The Evolving Character of a Nation. Why choose these particular words?

Erin Corrales-Diaz: A lot of thought and effort went into determining the title as a team, and a lot of initial ideas didn’t quite stick or express the ambitions of the project. I think “expanding” is really a crucial word in this since the project itself is presenting to our audiences a much more expansive purview of what American art is and can be.

Expanding Horizons: The Evolving Character of a Nation explores the dual themes of mythmaking and religion.

And as you’ve pointed out, it’s also “evolving,” another really crucial word because our project is meant to change over time and be fluid in a way that mirrors the United States and the Americas at large. Art is being made outside of borders and boundaries, and when we bring that thinking we get a more accurate view of all that was being created in the U.S. and beyond.

AM: A truer history is one ambition of the project, a thought-provoking experience that more accurately reflects art-making in this part of the world. How might this feel different than previous installations of American art at TMA?

Paula Reich: For the most part our previous installations in our American galleries have been pretty traditional, although we have integrated different media. Now we’re trying to expand whose stories we’re telling. We’re also dealing with a large time span, and how you talk about that succinctly and correctly. There’s a lot of complications there that we’ve tried to grapple with. And I’m sure that is among the things that will evolve over time with this exhibition.

Andrea Gardner: That’s right. Before, the American art paralleled our European art collection—it was centered on an aristocratic interpretation of what was valuable or beautiful, one that was very focused on creators of European origin without a real focus on indigenous peoples of America or other more marginalized voices. Certainly in recent years we’ve made a concerted effort to expand our holdings in those areas, but when you have an institution that’s

been around for more than 100 years, it takes time to change the configuration of an entire collection. This is part of that effort, to help us see something more true to the history and what was happening here and in the American continents at large.

AM: Storytelling is a huge theme of this reinterpretation of the American art collection—what it means, whose stories are told and why. What are some of the themes that are going to be explored here?

ECD: We went big and challenged ourselves to think about notions of myth-making and religion, two themes that reflect the types of American art that have been

collected in the Museum over its 100-plus year history. We felt these were broad buckets that would challenge the viewer to think differently about these works of art.

AM: What are some stories around a work of art you’ve seen grow or evolve thanks to this fresh look at the collection?

ECD: One example is the Thomas Cole painting The Architect’s Dream, a beloved highlight of the collection. A challenge curators face is when a label is only 75 to 100 words long, there is only so

9 Toledo Museum of Art

“”

Art is being made outside of borders and boundaries...

much story you can tell. The label was correct previously, but I wanted to focus on something no one really talks about in this painting, which is the Gothic cathedral shrouded in shadow. Where was Cole coming from, and why is this particular architectural form shadowed? What is that dichotomy he might be suggesting? Just that pivot from provenance and history to what’s talked about in the work, and considering the religious underpinnings of the painting, will give viewers an entry into thinking about the undeniable influence of religion on American history, politics, and culture.

AG: It’s quite novel. While many museums are exploring mythmaking in American (art) history, very few have yet engaged with religion as a principle theme. We went with one more common theme and then one that was less well-charted territory, and challenged ourselves to discuss the subject in a new way, because so much of our collection is composed of religious art.

AM: What other stories did you discover over the course of this project that surprised you?

ECD: The Henry Ossawa Tanner painting The Disciples on the Sea was crucial. It’s this amazing work by a Black American artist who was an expatriate. He lived in Paris for the vast majority of his life because he felt less racial discrimination in Paris, and when we talk about Tanner in the histories of American art, it’s often through two works out of his entire career, two paintings that deal with genre scenes, scenes of everyday life of Black Americans.

But that does not make up the body of this work, a vast majority of which is about Christianity. Why specifically in the United States do we not think of this artist as a religious artist? That’s one of the questions we’re exploring.

AM: You collaborated with some living artists to consult on the project. In what ways did outside expertise shape the installation?

ECD: We tried to use objects in our own collection as much as we could, but we really wanted to make sure we were representative of American art even in places where our collection might not be yet, like Indigenous American art. So we rekindled a relationship with the Denver Museum of Nature and Science (DMNS) to borrow several Navajo weavings that will rotate on and off view within the display. [Since the weavings are light sensitive, they cannot be on view at all times.] DMNS then connected us with two Navajo weavers, D.Y. Begay and Lynda Teller Pete, and they curated that particular part of the space, selecting which weavings to display, writing the interpretation, and advising us on how to display the works. Allowing their expertise to shape that part of the project really enhanced it.

AM: The installation design is really built around visitor feedback. How will viewers be part of how this experience evolves?

PR: We’re very upfront about that in the language that we’re using in the introduction to the space. We’re saying we want visitor feedback and we intend to act on it. The idea is we will be re-evaluating on

a regular basis. We’ve also been thinking about this as a kind of pilot project to look at how this informs the rest of our work in the Museum, especially around interpretation.

ECD: I think unlike a lot of installations or exhibitions, this is truly a work in progress. We’re coming to our community with a certain level of humility, and we’re hoping to have them provide us some of that context. I’ve never done a project quite like this, where the audience is so much a part of the installation.

AG: And this is intended to be up for a long time, and so that’s part of the opportunity as well. We will want to refresh it, and we will be incorporating audience feedback in the iterations that are to come.

AM: How will visitors get to engage?

PR: We’re giving viewers a few different ways to supply us with their insights, from traditional printed cards they can write on to digital stations that will ask more specific questions, and ways to follow up so they can give more direct comments. You’ll even be able to see people’s answers on a monitor so you can keep track of how people are responding to certain concepts.

AM: It seems to be breaking ground in some ways, in that feedback was typically solicited for temporary exhibitions on a temporary cycle. This project’s impact seems like it will be deeper.

AG: It is more unusual to be soliciting feedback on collection installations. For one, they don’t

10 Art Matters / THINK

often get refreshed as frequently. And second, the historical way of looking at it was the curators were the experts and they would present that work to the public for them to learn; it was not reciprocal. This project points to the evolving nature of curators, who are now seen as thought partners and stewards of a dialogue with the audience. That’s the future of museums, and that what we’re experimenting with now.

PR: We are also integrating accessibility. We have 3D-printed replicas of a couple of the works that people can touch, tactile reproductions of a few of the paintings that will be available for people with blindness or vision impairment to request, and we also have audio, verbal descriptions of some of the works. We’ll be adding more of these later on.

AM: Will things look visually different than a typical installation?

PR: The approach is similar to a temporary exhibition in terms of the way we’re using graphics and color to really highlight and give different context for our collection. Things like having relevant quotes reproduced on the wall or visually interesting panels that give additional context are all elements borrowed from temporary exhibition design. They not only draw attention, they underscore themes in the gallery.

ECD: We’re going to have two videos as well that will set the stage for both the themes. One addresses the highly personal nature of interpreting a work of art by recognizing that everyone

brings certain experiences— “baggage” as the video puts it— with them into a gallery. The other looks as how this operates at the institutional level, exploring what goes up on view, what remains in storage, and why.

AM: You’re also pursuing feedback early—how will you gather that and how will it influence the installation?

ECD: I really want to position this space as a place of curiosity, inquiry, discovery, and surprise, even in the exhibition design. That’s what makes me excited about sharing this.

AG: Yes, and thought-provoking discussions in a trusted, safe space. Feedback tells us that museums are appreciated as a trusted institution and partner in that

PR: We conducted three focus groups that were crucial in clarifying some things for us, including that people are really interested in challenging concepts.

AG: And that people view museums as a place that challenging thought should happen. The participants in the focus groups spanned education level, race, socioeconomic level, even membership, which is quite different than relying on feedback from those who are already stepping foot in the Museum. It was a very positive and productive interaction that I think we will continue in the future.

AM: What is the ultimate aim for the project, your ultimate hopes?

dialogue, along with institutions like libraries and historical centers. So we wanted to bring that conversation to TMA and it came to the foreground of this project.

AM: What can people look forward to in terms of programming?

AG: We’re going to be discussing the project more deeply at a symposium on July 21, where other museum professionals will gather to speak and reflect on these types of projects that are happening at museums across the country. It’s free and anyone interested is encouraged to attend as we hopefully continue and evolve this work of expanding horizons for all of us.

11 Toledo Museum of Art

The Disciples on the Sea, Henry Ossawa Tanner

(American, 1859-1937), about 1910. Oil on canvas, 21

5/8 × 26 1/2 in. Gift of Frank W. Gunsaulus, 1913.127

In the Studio: Beth Lipman

12 Art Matters / THINK

Guest Artist Pavilion Project (GAPP) resident

Beth Lipman talks to us about her forthcoming TMA installation ReGift, opening August 12.

The relationship between Toledo and glass is a long and storied one, containing history in both industry and art. How and who we remember in that history are questions that spurred Wisconsin-based artist Beth Lipman to create her latest project as the Toledo Museum of Art’s GAPP resident.

The seeds for her site-specific installation, titled ReGift, were planted in 2018, when her research on Museum co-founder Florence Scott Libbey began. The resulting glass components were created across multiple studios—some pieces made during her guest artist residency in the TMA hot shop in 2022 and others in her own studio in Wisconsin. They will form a recreation of the parlor the Libbeys occupied together, sized between miniature and full scale. The project fulfills the GAPP residency’s

ultimate aim: making space for experimentation in glass.

Lipman’s work has been acquired by numerous museums including the Corning Museum of Glass, Brooklyn Museum of Art, Kemper Museum for Contemporary Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Jewish Museum.

Art Matters: The muse for your GAPP project, Florence Scott Libbey, died in 1938. How did someone who lived nearly a century ago inspire this work?

Beth Lipman: Obviously I’m coming in as an outsider, but it seemed to me that the general focus on the founding narrative of the Toledo Museum of Art was on Mr. Edward Libbey1, even though his wife Florence was a massive part of it. ReGift is just a way to call attention to someone who perhaps is a little bit more invisible and to introduce the visitors and the community at large to her contributions. It also links to the City Beautiful movement2 , which swept across the country nationally at the turn of the century, to Florence’s mission and view.

AM: Where does the idea of regifting come into play?

BL: The real linchpin for the project came when I discovered through the Museum’s historian, Julie McMaster, that some of Florence’s only pieces of furniture that she gifted upon her death to the Museum were deaccessioned in the 1990s. Among what was still left in the archives was their custom illustrated bookplate, which was the genesis of the sculptural installation. It provides the only existing image of the interior of their home when they lived there. Some of the furniture that was deaccessioned is featured in that bookplate. ReGift is symbolically regifting these objects, that story and the identity of Florence back to the community and institution. It’s a way of revising communal priorities. What is worth preserving? What has been marginalized?

AM: In what ways did you feel connected with Florence during your research?

BL: I think she was possibly a simpatico soul, clearly passionate and curious in a way I can identify with. Also, maybe it’s a bit of a romantic lens on the time, but it seemed her age was a period of great optimism in some ways. She lived through the second industrial revolution, with an overt

13

Lipman

Toledo Museum of Art

Photo: Rich Maciejewski

embrace of the ideas of socialism and democracy. The City Beautiful movement led everyone to believe that they could make their life a little better by beautifying or creating, caring for the environment, caring for one another.

AM: How does that differ from what you perceive today?

BL: We are not there anymore. The fulcrum has pivoted to a valuation of autonomy and individualism, an egocentric take. So it’s not just about Florence, in some ways it is also about activating the institution to reengage the values that were lost over time, a kind of collective, communal empathy.

AM: Let’s talk about your other influences and references. You cite the decorative arts as a source of inspiration, though they’re often dismissed as less serious than some other art mediums.

BL: Decorative arts are historically the underdog, particularly in Western European culture, and there’s a lot of power in that. Decorative objects manifested for very different reasons than traditional fine art. Every object in the decorative field is created with some intention of negotiating the human body, whether it’s used functionally or to beautify a space. The human figure will never be represented in my work, because objects are surrogates for a human body, basically.

AM: You also mention deep time as a reference.

BL: Deep time is a term that was coined by John McPhee in his book about geological time, called

Basin and Range. When you factor in the age of the earth, it’s mostly pre-history or pre-human with the smallest little shred of time that humans have been on this planet. All of my work deals with time. I use different points in time and history to investigate the present moment. My initial investigations were

at the Smithsonian Natural History Museum, which led to the incorporation of depictions of paleo flora, plants that existed through five mass extinctions for hundreds of millions of years.

A thousand years from now or post-history, what are all of these objects that we surround ourselves with, that we value, what are they going to mean after humans are gone? It becomes a layer of detritus, another layer of strata within earth’s time. A lot of the recent work involves ways of compressing the visual representation of what came before, where are we now, what could come after.

are they going to mean after humans are gone?

through the genre of still life, which is constantly reminding you that life is brief. All the symbolism—the candle wick with the smoke, the fire just burnt out, the fly eating the grape—these are symbols of entropy, basically. These types of still lifes, vanitas, all define time or the fleetingness of time.

AM: What are some ways you’ve communicated that in your own work, how has that inspiration emerged?

BL: In the mid-2000s, I read Elizabeth Kolbert’s New Yorker essays about climate change. It became urgent to express this existential threat. How to incorporate the language of deep time? It led to a residency

AM: Why do you choose to work in colorless glass?

BL: Colorless glass or glass that has very little color invokes a liminal state. It is essentially a distillation of an idea. It is simultaneously something that you are seeing through yet you’re unable to fully grasp it at any given time because the forms change with light and the body’s movement. It’s constantly elusive thanks to the way light travels through and is reflected back through the material.

AM: You mentioned the value of colorless glass providing a liminal moment for the viewer, being something more elusive than other kinds of materials we might be able to look at and feel secure that it looks just one way. In what ways do you feel liminal as a person?

BL: One’s relationship to time could be construed as liminal. It spans to eternity and is also over

14 Art Matters / THINK

“”

What are all of these objects that we surround ourselves with, that we value, what

in a blink of an eye. The nature of creative practice in the studio is a process of going in and out of a flow state.

AM: Your mother and grandmother were both artists; how did that come to influence your own personal career path?

BL: I think what my mother gave me in particular was confidence. She designed and made limited edition hand-painted objects that were sold both wholesale and retail. She financially supported our family with her art, and so her example made it very easy for me to pursue an artistic practice. My parents were unwaveringly supportive.

AM: Beyond the Museum and what you discovered there, what else have you found yourself enjoying about Toledo?

BL: You have such good food! I am a huge fan. The Middle Eastern markets and their fatayer and flatbreads are so great. During my residency visits, part of me thought maybe I should move to Toledo.

15 Toledo Museum of Art

1. Edward Drummond Libbey (1854–1925) and Florence Scott Libbey (1863–1938) were prominent Toledoans who helped found the Toledo Museum of Art. Libbey is considered the father of the Toledo glass industry; Scott was a philanthropist and daughter of Jesup Scott, founder of the University of Toledo.

2. The City Beautiful movement was sparked by architects, landscape architects and reformers interested in organizing more intentional urban planning between the 1890s and 1920s.

Lipman and TMA’s glass studio artists working on components of ReGift in 2022. The installation will

recreate Florence Scott Libbey’s parlor.

16 Art Matters / DISCOVER

Discover

Discover

Orbit

Daniel

17 Toledo Museum of Art

Owen Dailey (American, born 1947), 1987. Glass, sand-cast in iron form, sandblasted, acid-polished; paint on theater cloth, stretched over board. H: 8 ft.; L: 16 ft. Gift of Tishman Speyer Properties, 2015.35

A New Space for Community

Robert C. and Susan Savage have provided a generous gift to renovate the Community Gallery, creating a space to engage Toledo area artists in new ways

The aim is not just space to display and sell art, but also to expand outreach and cultivate meaningful conversations with and about Toledo artists. To select work to exhibit, TMA team members will make connections with potential Community Gallery artists in their studios, building a relationship that will allow a dialogue about the artist’s work, career, and growth.

The Toledo Museum of Art is debuting a new Community Gallery, thanks to the generosity of local donors Robert C. and Susan Savage. The space will display pieces by local and regional artists and allow them to sell their work, building a collector base from the large audience of art enthusiasts TMA draws each year.

“This will provide a space both for the Museum to connect with the artistic community more broadly and for the public to more easily explore the artwork being made in our region,” the couple said.

“We believe this space and the programming that will animate it will contribute to the growth opportunities for local artists in

profound ways. The Toledo region boasts extraordinary artists, many of whom have gone on to national and international renown. We hope this space will allow more Toledo artists to reach new heights.”

The gallery will debut under a new name in their honor, the Robert C. and Susan Savage Community Gallery, with the funds supporting the design and construction of the upgraded space on the Museum’s lower level. A gallery space devoted solely to the work of emerging artists will be a significant boon to the creative energy of local artists working in the area, one of the reasons the Savages pledged to support the project.

“It’s a generous gift, one that will have a major impact on opportunities for exposure for local artists,” said Adam Levine, TMA’s Edward Drummond and Florence Scott Libbey director and CEO.

“It’s not just the dedicated space that is meaningful; it’s another act by our community showing the commitment to TMA as an anchor institution in supporting our region.”

The reimagined gallery bolsters a relationship with local artists that extends back to the Museum’s founding in 1901. Creating a new space devoted solely to the work of up-and-coming artists from the region is also part of TMA’s Belonging Plan, a strategic effort to foster a culture of inclusion and representation on the gallery walls.

“This is another chapter in an ongoing dialogue with artists in

18 Art Matters / DISCOVER

TMA Director Adam Levine with Susan and

Robert C. Savage.

Photo: Ben Morales

the Toledo area,” Levine said. “We hope this will be an opportunity to reinvigorate and reopen that conversation with local artists, and strengthen our ties with the local creative community.”

For Findlay artist Amber Kear, founder of art and design

organization the Hysteria Company, the platform this new gallery provides for local artists will have an immense impact.

“It allows artists another opportunity to connect with each other in community, on a deeper level of understanding, which

is part of the true essence of our belonging,” Kear said. “And the programming that accompanies the exhibitions will have an impact on the future of our young, growing artists in this region, too.” Amber will be the Community Gallery’s next featured artist in May.

19 Toledo Museum of Art

A visitor explores local art in the new Community Gallery. The space reinvigorates the dialogue between the region’s artistic talent

and the city’s anchor arts institution.

“”

[This gallery] allows artists another opportunity to connect with each other in community, on a deeper level of understanding.

1912

TMA moves from its rented spaces downtown to its first official (and very grand) building on Monroe Street, still its home today. Community members lined up outside to experience the opening day; a private party invitation for notable locals featured an individual, hand-drawn etching.

1920s

Before 1933, if the Museum wanted to host a party they took it to one of the buildings nearby—like the Toledo Club or Secor Hotel— since TMA had no catering facilities. In this image we see a gathering to drive membership; note the all-male guest list, reflective of the gender and racial disparities of the time.

AGrand Affair

TMA’s Cork-Popping History of Hosting

Partying like it’s 1999 looks very different than partying like it’s 1912, especially when it comes to the fêtes that dot the Toledo Museum of Art’s 122-year history. The spirit of celebration didn’t gain momentum until the second half of the 20th century, when attitudes around art conservation and what was permissible in the galleries (in: food, out: smoking) began to shift. Museum Archivist Julie McMaster dug into the depths of our scrapbooks, photos, and news clippings to help us explore the history of shindigs at TMA.

20 Art Matters / DISCOVER

Today when couples dream of their wedding, it’s no surprise to see the Museum on their list of ideal venues. But in the 1920s, getting married at TMA was unheard of. There was one exception made when in 1926 the director at the time, Blake-More Godwin, wed fellow TMA employee Molly Ole in the since-restructured Gothic Hall.

The landmark El Greco of Toledo exhibition draws intense crowds (nearly 183,000 people, 70% of them from outside Toledo) and kicks off this flashy party decade with a huge public celebration of the opening.

2005

TMA hosts its first Juneteenth party with outdoor performances, food, and activities, becoming the precursor to the Museum’s annual summer block party that invites the community for a campus-wide celebration.

The founding of the TMA Aides (now known as Ambassadors) brings a new sensibility to the Museum’s fundraising efforts, one rooted in hospitality. They began to organize more receptions, hosting early President’s Council dinners, including one of the first public servings of alcohol in the Museum in 1969.

Fast forward to the 100-year anniversary of the Museum, when the Peristyle was transformed into a dance floor (lowerfloor theater seats were covered with wood planks) and the ball gowns and tuxedos were out in full force.

Today, the Museum is no longer host to only its own special moments, but serves as the backdrop for community members’ wedding vows, memorials, TED talks, and more.

21

2023 1926 2001 1982

1957

@vibegardenimages

Toledo Museum of Art

22 Art Matters / EXPERIENCE Experience

Part of TMA’s recently refreshed American Gallery 29, now open.

Young

with a Bird and a Dog

23 Toledo Museum of Art Experience

Lady

John Singleton Copley (American, 1738-1815), 1767. Oil on Canvas. 48 × 39 1/2 in. Purchased with funds from the Florence Scott Libbey Bequest in Memory of her Father, Maurice A. Scott, 1950.306

A Dawn Omen: Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg & Machine Auguries

In Machine Auguries: Toledo, artist Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg uses artificial intelligence to get her audiences to engage with what we might lose—before it’s too late

24 Art Matters / EXPERIENCE

Ginsberg

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg has become something of a connoisseur of chirps and trills.

She’s been listening to thousands of recordings of real birdsong to create the data set that will feed her installation, Machine Auguries: Toledo, and the artificial intelligence that Ginsberg has trained to recreate the dawn chorus.

Ginsberg employs a Generative Adversarial Network (or GAN) network with her longtime collaborator Przemek Witaszyk, a string theory physicist in Kraków, Poland. With GAN, two neural networks talk to each other—a kind of call and response. One network makes a sound, and the other network responds in a kind of one-upmanship moment to produce the same sound or image a little better. Each cycle introduces improvements; in the language of tech, these are called epochs. Neither the artist nor the string theory physicist are in control of the process and what emerges.

The UK-based artist, who goes by Daisy, has been examining

the fraught relationship between technology and nature—in other words, between the things we humans invent and the world that surrounds us. In her explorations, she seeks to help audiences interrogate the costs of approaching our environment with a relentless will to make it more comfortable and more convenient.

Machine Auguries, an installation she first presented in 2019 on a smaller scale at Somerset House, London, will make its U.S. debut at the Toledo Museum of Art on April 29. Using light and sound, the installation recreates the experience of the dawn chorus, essentially a daily singing competition birds engage in every morning during spring and early summer to defend territory and seek mates.

The Toledo exhibition will be even more ambitious than the work’s first iteration: larger in scale, with improved technology that’s more experimental, generating longer and more accurate birdsong. The Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology has been an important collaborator; it holds the world’s largest repository of animal recordings in the world. So has the Black Swamp Bird Observatory, which helped Ginsberg capture the song of local and migratory Northwest Ohio birds—warblers and cardinals, catbirds and vireos.

Field recordings include the many additional noises being fed into the machine and crunched up, so to speak—the vibrations of traffic, the rustling of leaves—and once translated causes the artificial version of the dawn chorus to evoke

a dimmer, darker alternate reality.

That was the intention, in some ways. “A dawn chorus is unique—it happens each day with different individuals in a particular habitat,” says Ginsberg. Attempting to match it perfectly is futile. “You can’t recreate it.”

Ginsberg’s childhood was spent on a farm, in the English countryside outside London, though the family didn’t raise any animals– just shiitake mushrooms. She spent many of her teenage weekends plucking them from logs in the woods. Farmed in the traditional Japanese method, their fickle growth and mercurial nature were sometimes frustrating. (“A rainy Sunday meant suddenly a mushroom-picking emergency,” she says.) There were advantages, though: out there, communing with nature, she could make her own little world and be inquisitive. “It was formative,” she says. “I was the kind of kid that needed to know how everything worked.”

Her focus on why and how things work propelled her into into a lifelong inquiry around what we often take for granted. What is progress, and why do we measure it the way we do? Who defines

25 Toledo Museum of Art

“”

We need creatives to engage with [AI] tools so that there’s more than one possibility.

“better”? These interrogations form the foundation of her practice, in her artwork, writing, and curating. She explores them in collaborations with scientists, engaging more deeply with the purpose and effect of our march toward progress. While this is regularly described as movement forward, Ginsberg estimates that this continues without enough consideration toward impact. Genetically engineered bacteria, synthetic organisms devised to help conserve nature, artificial intelligence—she’s demanded we answer more deeply for how we are “improving” the world and at what cost.

After undergraduate studies in architecture at the University of Cambridge and a stint as a visiting scholar at Harvard University, she earned her MA and PhD from London’s Royal College of Art, where she completed Better, her PhD project. In it she explores how different individuals’ visions for improving the world shape how and what ultimately gets designed. “Daisy’s practice is addressing

the critical and urgent—but also enduring—issues of our day,” says Jessica S. Hong, curator of modern and contemporary art at TMA. “And in her work there is this interesting coalescing of the technological, through artificial intelligence, with environmental concerns, which are existential. I think it’s an interesting approach, and a thoughtful one.”

Her deft hand for taking highly technical or scientific tools and manipulating them to better understand our relationship with the natural world is meant to provide an opportunity. To pause, to consider, to redefine the way we measure our own advancement. She has exhibited internationally, including at MoMA New York, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, the National Museum of China, the Centre Pompidou, and the Royal Academy.

“Modern humans, postenlightenment Western humans, have been very busy trying to free themselves from the natural world,” she says. “The big flaw of the

myth of progress is that we’re not measuring all the things that really allow our own long-term uplifting because we have destroyed our natural environment. My work is a critique on measurement in some ways and how we have been so focused on certain measures that we have forgotten our natural world. We don’t spend time considering all our conflicting ideas of what really is better.”

Working with AI creates ethical and moral questions, existential problems that Hong says stimulate Ginsberg and push her in the themes she interrogates in her work. Like the artist, the curator believes that these tools need to be examined outside the tech space.

“AI is the tool she uses to communicate the concerns that ground her practice,” Hong says. “It is a material that artists are utilizing, like the camera. And for a long time photography experienced a lot of push back as a ‘fine art’ medium. Granted there are very scary, serious consequences that can also potentially come of AI, but I think because of that it is important that it not be relegated to the tech space only. We need creatives to engage with these tools so that there’s more than one possibility.”

26 Art Matters / EXPERIENCE Installation view, 24/7: A Wake

Up Call For Our Non-Stop World, Somerset House, 2019.

Photo: Luke Walker.

“”

...the most interesting thing to me is to draw attention to something we’re at risk of losing, not necessarily the technology itself.

In Machine Auguries, Ginsberg is wrestling with a very big idea: the end of the world as we know it.

The machine in Machine Auguries comes from the artificial intelligence Ginsberg employs, AI that has been taught how to mimic the dawn chorus. The auguries— or omens—emerge from the competition between the authentic and the simulated. The experience of hearing this mutating birdsong is an emotional one.

Though artificial intelligence is a tool, it’s ultimately not the inherent point, she says.

“It’s a piece about birds, and I’ve chosen to do that with AI,” says Ginsberg. “But the most interesting thing to me is to draw attention to something we’re at risk of losing, not necessarily the technology itself.”

Given the weighty subject matter, you might expect a more dour figure to appear on the video call that was scheduled one winter morning this January to discuss her upcoming exhibition.

But the person who appears on screen feels altogether more lighthearted. She’s seated in her London office in Somerset House Studios, where she’s undertaking a residency, her seafoam green sweater contrasting the season’s gray skies. After a morning of backto-back meetings, she politely asks to excuse herself to “hunt for a biscuit”; a cure for early afternoon hunger pangs.

We discuss how in the summer of 2022, Ginsberg experienced the

heat wave that struck the UK and Europe, some of the most intense temperatures ever recorded in London. She found it frightening to step outside.

“It was a really strange feeling,” she says. “You emerge into this hot, hot street and it’s wrong. There’s something really unnerving. It was like everything was upside down. It’s not how the world is meant to be in this particular place. You went to the parks to walk the dog and it looked like a savannah, it was parched.”

There isn’t much of a dawn chorus left in London—she and her partner moved outside the city, where they can still hear birdsong. The bugs that characteristically dirtied windshields on drives through the British countryside are vanishing;

car windows remain relatively clean now, she informs me. Bugs, and birds, are disappearing.

It’s a shifting baseline, changes happening gradually over time until one day you realize you haven’t noticed the major transition taking place right before you. It makes her feel listless, she says. So she returns to the work, the place she communicates her concerns and can create a true dialogue with her audience.

“There’s a more nuanced point, which is that we need to be living with nature. Once it’s lost, it’s lost,” says Ginsberg. “You can’t recreate the natural world because it’s a constantly ephemeral and changing thing. We need to look after it as our greatest priority.”

27 Toledo Museum of Art

UK artist Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg.

Photo: Nathalie Théry

On View & Upcoming

Mark your calendars for the opening of these inspiring new exhibitions and installations at the Toledo Museum of Art.

Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club

June 3–Sept. 3, 2023

Experience Nigeria in the 1960s through the artistic exchange that took place between African American artist Jacob Lawrence and Mbari Artists and Writers Club members in Nigeria. The show features 125 paintings, sculptures, reliefs, and works on paper by artists like Lawrence and Duro Ladipo, Twins Seven-Seven, Muraina Oyelami, Asiru Olatunde, Jacob Afolabi, and Adebisi Akanji. It also includes letters Lawrence wrote to his friends in the United States about his experiences in Nigeria and copies of Black Orpheus (1957-67), the Nigeria-based literary journal that showcases the works of modernist African and African Diasporic writers and visual artists.

Together, the objects transport visitors to Nigeria during a time when several countries in Africa and around the world were establishing their independence. Black Orpheus displays how artists grappled with representing their respective national and cultural identities while depicting visually striking works during the beginning of the postcolonial period throughout the African continent and other parts of the world. The show is the first museum exhibition of Lawrence’s Nigeria series, exploring a littleknown period in his life that included the nine-month stay in Nigeria in 1964 documented in this exhibition.

Through the works on view, visitors will gain insight into Lawrence’s conversations with Nigerian, Ethiopian, Sudanese, and Ghanian artists and discover how those interactions influenced him long after he returned to the United States.

28 Art Matters / EXPERIENCE

Market Scene , Jacob Lawrence (American, 19172000), 1966.

Gouache on paper, Chrysler Museum of Art, Museum purchase

2018.22. © 2022

The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence

Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Seeing Stars, Divining Futures

Feb. 3–June 18, 2023

From representations of the zodiac to tarot cards and images of fortune tellers, Seeing Stars, Divining Futures highlights the long history of human interest in the cosmos and their impact on earthly affairs. The exhibition showcases works from the Toledo Museum of Art’s collection that demonstrate the integration of art and divinatory practices across eras and cultures.

Expanding Horizons: The Evolving Character of a Nation

Opens Mar. 18, 2023

Explore new ways of understanding complex histories through the themes of mythmaking and religion. More than 80 objects from TMA’s collection offer a powerful lens for discovering a multiplicity of American stories and voices.

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg–Machine Auguries: Toledo

Apr. 29–Nov. 26, 2023

The natural dawn chorus is slowly taken over by artificial birds in Ginsberg’s stirring, immersive installation that uses artificial intelligence as its medium. Tickets are free for Museum members and $10 for non-members.

Beth Lipman: ReGift

Aug. 12, 2023–Sept. 1, 2024

ReGift recreates a three-quarter life-sized diorama of the parlor in TMA founders Edward and Florence Libbey’s Old West End house. It also symbolically reinstates works once owned by TMA, emphasizing Florence’s involvement in building the Museum’s (and Toledo’s) legacy.

29 Toledo Museum of Art

Museum Store Spotlight: Craig Fisher

Loving art can go beyond admiring it in museum galleries. Becoming a collector supports the work of living artists and allows you to bring creative expression home. Original art by more than 250 emerging and established regional artists is waiting in the Museum Store’s Collectors Corner—sculptures, glass, prints, photographs, pottery, and more will spark thought, creativity, and wonder. For now, enjoy exploring the work of Craig Fisher in this season’s Museum Store Spotlight.

30 Art Matters / EXPERIENCE

“I draw them and then I discard them,” says Craig Fisher. The artist is referring to the sketches and concepts that inform his intaglio works—iterations he remains determined to not get attached to.

He resists investing too much in one sketch because the forms are constantly mutating, serving more as loose mental road maps than as final blueprints, which makes the results—nearly three feet tall, elaborate etchings that emerge from 600-pound steel rollers— even more awe-inspiring. Fisher commands a level of detail in his creations that hint at a complex, maze-like imagination.

The printmaking machine, the one holding the aforementioned massive steel rollers and the copper-etched master plate, gives Fisher an intimacy with each print, as he pulls them by hand one at a time. “There’s no doubt that a well-made ink jet print, on archival paper stock, looks every bit as ‘rich’ as a hand-pulled etching,” Fisher writes. “But I will bet that the signed etching has more spirit and character.” It’s this embrace of old-world techniques and modern, fantastical story that make Fisher’s works so compelling.

His history ties him closely with the Toledo community—he studied fine arts at the University of Toledo, where he focused on printmaking, painting and graphic design, with a stint at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. His work is part of the collections of the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum, Purdue University Galleries, and others. You can shop Craig’s works and more in person or online at tmastore.org

31 Toledo Museum of Art

All images courtesy the artist.

Imperial Whirlygig , Aquatint etching, 18 “ x 24”

L’esprit de Conquête, Etching, 34” x 31.5”

TMA Glass Studio Hits the Road

The “baby dragon” is scheduled to make appearances all over the region this summer, at Jones Leadership Academy, Owens Community College, the African American Festival, and Ann Arbor Arts Fest.

Baby dragon, in this case, is the pet name the Toledo Museum of Art’s glass artists have given their fiery mobile glassblowing furnace. It lives inside the TMA outreach truck, outfitted for demonstrations and community glass experiences around the region—in high school parking lots, on festival grounds, at community colleges, libraries, and beyond—expanding TMA experiences outside the downtown Toledo campus.

“Kids faces light up when they see us,” said Kacey McCreery, the TMA glass studio outreach artist. “We’ve equated it a bit to an ice cream truck—that is the response we’re trying and hoping to get out of the community, excitement and enthusiasm for the Museum. And we’re seeing it happening.”

It took one year to ensure the new truck was adequately equipped with the right tools and the

ability to haul them. (Baby dragon holds about 40 pounds of molten glass and takes three and a half hours to heat up, quite a contrast with TMA’s glass studio furnaces, which house 700 pounds of glass and take 24 hours to fully fire up.) Though it was purchased in 2020, after the pandemic began use of the truck was delayed until spring 2022, the same year it earned its new, award-winning wrap, giving it a distinctive aesthetic on the road.

At schools, libraries, and other locations, TMA’s glass artists do live demonstrations and share information about public programming, classes, scholarships, and exhibitions.

“It brings TMA into the community, and personally invites people back to the Museum,” McCreery said. “To have this truck out in your neighborhood, with TMA team members extending a personal invite to the Museum, is really special.”

TMA’s outreach truck is supported in part by the generous donations of the TMA Ambassadors and 5/3 Bank; the mobile glassblowing furnace is supported in part by Majida Mourad in memory of Ellie Mourad.

Art Classes and More: Learning at TMA

The Toledo Museum of Art offers art classes and professional development workshops for all levels, with offerings for children as young as 3 all the way up to adults. Practice drawing, try your hand at sculpture and mixed media, create objects in metal or glass, and more. Come as an individual or sign up as a family, a couple, or with a friend. Scholarships are available to help cover class costs for those who qualify, and there’s a course to suit every schedule, whether you need weekday options or prefer a weekend experience.

To explore class options or sign up, visit tickets. toledomuseum.org.

32 Art Matters / EXPERIENCE

Art Matters Staff

Director of Brand Strategy: Gary Gonya

Feature Writer and Editor: Alia Orra

Marketing Manager: Crystal Phelps

Design: Aly Krajewski

Send comments, questions, or inquiries to Gary Gonya ggonya@toledomuseum.org

© Toledo Museum of Art. All rights reserved.

P.O. Box 1103

Toledo, Ohio 43697

Forwarding Service Requested

© 2023 Toledo Museum of Art

ON THE COVER

Blind-Man’s Buff

Jean-Honoré Fragonard (French, 1732-1806) about 1750-1752, Oil on canvas

In the 18th century, the game of blind man’s buff (or bluff) became the symbolic arena for courtship and the amorous amusements of lovers (relating to “love is blind”). Fragonard develops the theme of the fleeting nature of youthful love by decorating his composition with spring flowers.

34

The Toledo Museum of Art • 2445 Monroe Street • Toledo, Ohio 43620 • 419.255.8000 • toledomuseum.org

On view: Gallery 26, Rotunda