17 minute read

Jamaica (Visual Analysis

The essence of all the responses, though slightly varied, could be quickly summed up in one-word—

“escape, ” in keeping with Cooper’s observation that “indeed, tourism is often packaged in travel

Advertisement

brochures as ‘escape’ from the everyday anxieties of real living.”46

3.3. The Legacy of Colonization and Its Impact on Jamaica’s Tourism

Industry

Although present-day Jamaica is seemingly synonymous with “paradise, ” a tropical Eden to

escape mundane routines for many of its visitors, this was not always the case. As previously discussed in

Chapter Two, Jamaica welcomed many new inhabitants to its shores. With the influence of European

colonial power and the mass population transfer of enslaved Africans, Jamaica became a business,

economic, and financial hub for the trade of goods. This remained the island’s primary purpose for those

Europeans who ventured to its shores. The concept of Jamaica as a destination for enjoyment was far

removed from the minds of most Europeans at the time. Due to illnesses such as malaria, which induced

life-threatening fevers, and the ensuing high death rates, the country was deemed a “graveyard for

Europeans. ”47 The medical beliefs of the time attributed the main source of these illnesses to the tropical

atmosphere, advising most to avoid low lying coastal areas and beaches. Other factors characteristic of

tropical regions such as the intense sun as well as insects such as mosquitos, were all deterrents for most.

As one might discern, the endearing characteristics that make Jamaica a tourist hotspot today were the

very characteristics that repulsed its European inhabitants of the time.

However, with the development of industry, medicine and infrastructure came a slow

transformation in Jamaica’s tourism prospects. This was particularly important for the island, as with the

diminishing of the once-lucrative sugar industry and few other resources deemed valuable, the country

46 C. Cooper, Sound Clash: Jamaican Dancehall Culture at Large (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004). 47 Frank Fonda Taylor, To Hell with Paradise: A History of the Jamaican Tourist Industry (Pittsburgh; London: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1993, 16).

27

required another industry to support the economy. 48 The initial phase of change involved visitors, still

cautious of coastal locations, seeking respite in the island’s cool mountains. The island was soon marketed

by wealthy private investors as a place for affluent Europeans and North Americans to seek tropical health

spa retreats, particularly during harsh winters. The catalyst for Jamaica’s tourism industry occurred,

however, in 1890 when plans to host the premier Jamaica International Exhibition were materialized. This

represented the first time that the government pledged its commitment to the tourist sector by providing

finances and laws to stimulate growth. This shift in the country’s image as a “graveyard” brought forth

change in perception of the island.

49

Despite having several organizations created to promote Jamaica as a burgeoning tourist

destination, it was not until 1955 that an official consolidated board was created to operate the tourist

industry, the Jamaica Tourist Board (JTB). 50 Today tourism in Jamaica represents a thriving industry,

receiving over 4 million visitors in 2018 alone and proving to be the economy’s most lucrative financial

contributor.

3.4. Brand Jamaica: How Jamaica’s Tourism Industry Forms Its Global

Identity

As one might discern, image and perception play an important role in a country’s ability to engage

successfully in a competitive global industry such as tourism. The establishment of an official body such

as the Jamaica Tourist Board (JTB) had proven beneficial in projecting a seemingly unified image of

Jamaica. Thus, their development of “Brand Jamaica” plays a primary role in influencing the country’s

48 United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) and Caribbean Development and Cooperation Committee (CDCC), Restructuring Caribbean Industries to Meet the Challenge of Trade Liberalisation (UN ECLAC, 2005), https://books.google.tt/books?id=yWgSMwEACAAJ, retrieved November 29, 2020 at 12:20 pm. 49 Taylor. 50 Jamaica Tourist Board, 2016, https://www.jtbonline.org/.

28

sense of national identity, both domestically and globally. As is stated on the Jamaica Tourist Board’s

website, “The organization markets the uniqueness of destination Jamaica through creative programmes

and advertisements worldwide.”51 But while the strategies of the JTB are undeniably beneficial from an

economic and business standpoint, these strategies produce questionable social implications which are

discussed further below.

3.4.1. Nation Branding

Simon Anholt coined the term "nation branding" to describe “the sum of people's perceptions of

a particular country, using the areas of culture and heritage, exports, governance, tourism, investment,

and immigration as key markers. ”52 In other words, nation branding “is a marketing strategy that is used

for the main purpose of targeting external markets, with the end goal being to establish and communicate

a specific image of national identity. ”53 The term “image,” as it pertains to marketing, is widely accepted

to mean “what consumers perceive an organization to be visually and otherwise. ”54

In an increasingly competitive global marketplace, it is understandable that the JTB strategically

employs the concept of nation branding. However, where nation branding proves even more crucial to

the success of the Jamaican tourism industry is its implied role “as a powerful equalizer, providing a way

for lesser-known and economically weaker countries to compete with their powerful counterparts.”55

While these efforts have successfully garnered international attention, there are drawbacks in utilizing

the nation branding concept. As Aronczyk posits, “nation branding has negative consequences that

surface with the unaccountability of marketing experts in decision making; downplaying of components

51 Jamaica Tourist Board, 2016, https://www.jtbonline.org/. 52 Simon Anholt, ‘Nation Brand as Context and Reputation,’ Place Brand Public Dipl (2005, 224–28). 53 Somogy Varga, ‘Collective Identity and Public Sphere in the Neoliberal State’, Philosophy and Social Criticism 39 (2013, 825–45). 54 A. Ferrand and M. Pages, ‘Image Management in Sport Organisations: The Creation of Value’, European Journal of Marketing 33, no. 3/4 (1999, 387–402). 55 Anholt.

29

of national identity which do not project the desired image; and the reduction of national identity to a

single configuration.” 56 Through the process of simplification, many of Jamaica’s complex, layered culture

is ignored and thus leaves room for the formation of stereotypes by foreign onlookers. As Dinnie aptly

states, “What should prevail over stereotypes in successful nation branding is amplification of the existing

values of the national culture rather than the fabrication of a false promise. ”57

3.4.2. The Sun, Sea and Sand Marketing Strategy

As Cornwell and Stoddard observe, “the Caribbean region, with close ties to both North America

and Europe, has for a century been identified with sun, sea and sand tourism.” 58 Jamaica, as part of the

Caribbean region, is no different. This is evident in the responses to the question, “what do you think of

when you hear of Jamaica?” Most often, the immediate response of non-Jamaicans is “its warm, tropical

climate and its beaches.” In other words, its “sun, sea and sand.” This seemingly flippant response,

however, did not emerge by chance, but rather is the result of persistent and evidently successful brand

marketing by the JTB. Initially, Jamaica’s tropical climate had been disparaged by propaganda laced with

prejudicial undertones. Many wealthy North Americans and Europeans suffering from maladies visited

the island as a way to recuperate from their ailments.59 Intense campaigns to alter this perception were

later launched to reframe its warm climate as a health and wellness haven. These campaigns primarily

focused not on Jamaica’s coastline beaches, but rather its interior mountains and springs. Hence, Jamaica

was now deemed to be the new Riviera. Further attempts at redeeming Jamaica’s image and the viability

of its tourism were later pushed into marketing the country as a “winter get-away” in the premier 1891

Jamaica International Exhibition. Thus, the “sun, sea and sand” model was birthed. As Taylor states, “the

56 Melissa Aronczyk, ‘Nation “branding” to Promote States in the Global Market Has Serious Consequences for Social Diversity within European Countries’, Blog. London School of Economics (LSE), 2014. 57 Keith Dinnie, Nation Branding: Concepts, Issues, Practice (Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge, 2016, 93). 58 Cornwell and Stoddard (2007) 59 Taylor.

30

winter season was advertised as the best time to visit the island. With its perpetual summer Jamaica

offered a haven, boasting few days in the year when some form of outdoor exercise cannot be taken.”60

Despite the Jamaica Tourist Board’s changing campaign strategies throughout the years, the “sun,

sea and sand” model has always remained. However, this model does not come without its consequences,

particularly those facing the Jamaican people themselves. It is in this regard that Nettleford opined “Is the

Caribbean thus blessed? Some feel not. For one thing, visitors do not normally come, and are not

encouraged to come, to the region to “soak up” its culture. The marketing strategies have themselves

been soaked in something called ‘Paradise. ’”61 The introduction of the all-inclusive (AI) holiday concept

further bolstered the development of the “sun, sea and sand” marketing strategy. By definition, an all-

inclusive holiday includes travel, accommodations, and a substantial amount of food and drink, together

with activities such as entertainment, trips or sports coaching, which are booked when the reservation is

made. 62 As White stated, “The all-inclusive model was introduced to Jamaica by hotelier John Issa and

was inspired by the Club Mediterranean resort concept on the Spanish island of Mallorca during the

1950s.”63 Since then, AI has become one of the leading concepts dominating the island’s tourism industry

today. Much of the JTB’s overseas campaigns primarily promote its AI hotels and ultimately aim to target

a specific demographic with its allure of luxury and convenience. However, despite the convenience and

luxury appeal of AI hotels, other visitor demographics indicate a growing interest that is seemingly less

addressed by the JTB, but evidenced by the emergence of new business models in the visitor

accommodation sector.

60 Taylor, 31. 61 Nettleford. 62 P.W. White, ‘Stepping out from the Crowd: Re(Branding Jamaica’s Tourism Product through Sports and Culture, ’

Eastern Illinois Institutional Repository, 2015. 63 White.

31

3.4.3. The Case of The Exotic: Authenticity, Magic and Paradise as Recurring

Themes in Brand Jamaica (Visual Analysis)

As was abundantly clear from the visual analysis in Chapter One, Jamaica’s image is intricately

linked with lush, untouched tropical nature and landscapes, otherwise associated with “paradise. ” As may

be discerned from the historical analysis of the Jamaican tourist industry in the earlier sub-section, it has

taken some time to create this image of “tropical paradise. ” In fact, it results from the successful

implementation of nation branding and marketing strategies adopted by the Jamaica Tourist Board. It was

pertinent to assess these images and representations from a sociocultural perspective. As such, samples

were selected from previously run advertising campaigns (consisting of videos, posters and flyers) for a

critical examination of their meanings and significations.

According to Barthes (1977) “in advertising, the signification of the image is undoubtedly

intentional.” It can thus be understood that the JTB, through its campaigns and advertisements, have

selected images that it believes showcases “attributes of the product being advertised. ”64 Since its

establishment it has spearheaded quite a few campaigns to attract visitors to the country, namely:

1. Come to Jamaica- It’s no Place like Home (1955-1963)

2. Come Back to Jamaica, Come Back to Yourself /Make It Jamaica Again (1963-1975):

3. Discover Jamaica / We are More than a Beach (1975-1984)

4. One Love (1994-2003)

5. Once You Go, You Know (2003-2007)

6. Once You Go… (2008-2011)

7. Home of All Right (2012- present)

64 Barthes, 1977, quoted in Nickesia S. Gordon, Memories from Home: A Brief Collection of Jamaican Short Stories (Independently published, 2019, 32).

32

8. Heartbeat of the World

From the images which follow, it is apparent that each campaign era, although marked by

different slogans, all bore a similarity through their use of recurring themes—“Jamaica as authentic and

Jamaica as magical.” 65 These ideas were solidified through the use of imagery, dialogue, text and music.

65 Gordon, 37.

33

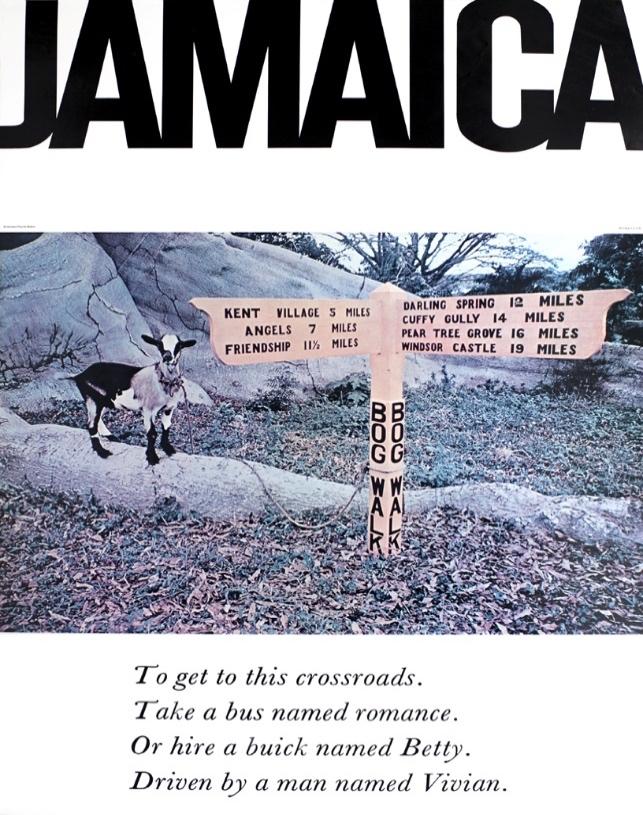

Image: 1950s Flyer created by the Jamaica Tourist Board Image: 1960s Flyer created by the Jamaica Tourist Board

Image: 1970s Flyer created by the Jamaica Tourist Board Image: 1980s Flyer created by the Jamaica Tourist Board

34

Image: 1990s Flyer created by the Jamaica Tourist Board

Image: 2000s Flyer created by the Jamaica Tourist Board Image: 2000s Flyer created by the Jamaica Tourist Board

35

3.4.3.1. Jamaica as Authentic

As Lee states, the idea of authenticity is “usually presented as an important part of the value-

added chain that tourist destinations can capitalize on in order to draw visitors to their product.”67 This

has been the strategy of the JTB as the concept of Jamaica as authentic has appeared in multiple ways.

However, this marketing approach presents problematic issues as “the search for authenticity in tourism

is based around myth and fantasy about a cultural ideal. ”68 Explicitly stated, authenticity is staged, much

like the campaigns undertaken by the JTB.

Using more specific references, I will highlight two advertisements launched by the JTB in its 1970s

“Come back to Jamaica. Come back to Yourself” campaign. Both videos, although highlighting varying

aspects of Jamaica, feature similar visual and linguistic strategies. The (video) concept centres around

showcasing various people (presumably from different (socioeconomic) backgrounds, professions, and

ages), each occupying different geographical locations in Jamaica. Throughout the videos, each person

recants short catchphrases in what can be assumed to be enticing to its viewer while an underlying melody

guides the videos’ transitions.

In the opening scene of Video #1 (see images shown below), a group of polo players are seen

riding horses. As the scene progresses, one of the players addresses the viewer with the statement “Come

back to gentility. “ The video proceeds with an additional seven persons making different statements of a

similar nature such as “come back to our people” and “come back to romance. ” However, the video’s

67 Lee et al. 2016, quoted in Gordon, 38. 68 Sharpley, 1994:127, quoted in Gordon.

36

penultimate statement made by an elderly man surrounded by children is most noteworthy. He states in

a cheerful tone “Come back to the way things used to be. Make it Jamaica again and make it your home.”69

69 Information and images for this section retrieved June 3, 2019 from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pokFsD1VHew&list=PLZADfMBb6_aSYNtAkAre1tYOoAr8BKkK8&index=2&ab_ channel=commercialclassics1975-1985

37

Image: Jamaica Tourist Board 1970s commercial: Video # 1-Scene 01: “Come back to gentility” Image: Jamaica Tourist Board 1970s commercial: Video # 1-Scene 02: “Come back to our beauty”

Image: Jamaica Tourist Board 1970s commercial: Video #1-Scene 03: “Come back to our people” Image: Jamaica Tourist Board 1970s commercial: Video #1-Scene 04: “Come back to hospitality”

38

Image: Jamaica Tourist Board 1970s commercial: Video #1-Scene 05: “Come back to our bounty” Image: Jamaica Tourist Board 1970s commercial: Video #1-Scene 06: “Come back to tranquillity”

Image: Jamaica Tourist Board 1970s commercial: Video #1-Scene 07: Come back to romance” Image: Jamaica Tourist Board 1970s commercial: Video #1-Scene 08: “Come back to the way things used to be. Make it Jamaica again and make it your home”

39

While Video #1 seemed to focus on capturing the alluring qualities of Jamaica’s people, Video #2

seemed to focus on the country’s natural landscapes. The first scene greets the viewer with a

mountainous terrain covered in lush greenery. The video continues by introducing eight different

individuals, all in different natural backdrops, making statements which seem to be aimed at enticing the

viewer with the offerings of Jamaican natural landscapes. Statements such as “Come climb up a cool

mountain and “Come walk up a waterfall” bear witness to this attempt.70

Image: Opening scene from the Jamaica Tourist Board 1970s commercial

70 Information and images in this section retrieved June 3, 2019 from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r5QZTL7jP3c&list=PLZADfMBb6_aSYNtAkAre1tYOoAr8BKkK8&index=1&ab_c hannel=retrorocker

40

Image: Jamaica Tourist Board 1970s commercial: Video #2-Scene 02: “Come climb up a cool mountain” Image: Jamaica Tourist Board 1970s commercial: Video #2-Scene 03: “Come let your spirit soar

Image: Jamaica Tourist Board 1970s commercial: Video #2-Scene 04: “Come back to romance” Image: Jamaica Tourist Board 1970s commercial: Video #2-Scene 05: “Come walk up a waterfall”

41

Image: Jamaica Tourist Board 1970s commercial: Video #2-Scene 06: “Come skim the prowess of blue waters” Image: Jamaica Tourist Board 1970s commercial: Video #2-Scene 07: “Come play in our playground”

Image: Jamaica Tourist Board 1970s commercial: Video #2-Scene 08: “Come feast on our friendship” Image: Jamaica Tourist Board 1970s commercial: Video #2-Scene 09: “Come to a place that could make your body feel cool and your spirit feel warm”

42

The linguistic codes for authenticity can be found in statements such as “Come back to the way

things used to be. Make it Jamaica again and make it your home.” Declarations like these are positioned

to evoke a sense of belief in the genuineness of what the country and its people have to offer its viewer.

Another notable statement was “come revel in unspoiled spaces. ”

Visually, the theme of authenticity is hinted at through the proliferous representations of

Jamaican landscapes- typically displayed as untouched and virginal. Such visual depictions invite the

viewer to imagine Jamaica as a pre-discovered space, much like it was prior to the country’s history with

European conquest and colonization. In fact, this visual tactic reflects much of the ideologies expressed in

travel writing emanating from Europe about postcolonial spaces- one which Pratt refers to as “the imperial

eye. ”71 These writings often highlight “Europe’s obsession with binary representations of place and space

that perennially casts them in the role of civilized versus uncivilized, developed versus

underdeveloped…”72

Use of imperial terminology is expressed even more explicitly on the website of one of Jamaica’s

most successful chain hotels, Sandals Royal Plantation. 73 The choice of name for the hotel is already quite

indicative of its marketing strategy as the use of the term “plantation” is a direct reference to the

properties on which Jamaica’s enslaved African people were forced to labour. Throughout the website,

the hotel presents itself as having “British colonial charm” and boasts that it is renowned for its “British

traditions of a bygone era”. When perusing the Sandals website, one would find prevalent use of

descriptions such as “colonial charm” and “colonial-inspired.”

71 Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (London: Routledge, 2007). 72 Gordon, 39. 73 The Sandals hotel chain was created by Butch Stewart and is a partner of the JTB. See http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/observer-west/sandals-partners-with-jtb-to-market-brandjamaica_207515?profile=1434

43

Image: Sandals Hotel website, retrieved July 19, 2019

Image: Sandals Royal Plantation website, retrieved July 19, 2019

44

Image: Sandals Royal Plantation website, retrieved July 19, 2019

45

Another notable observation that reiterates colonial ideology is the presentation of Jamaican

people as passive characters. As Gordon states,

There is a perennial sense of waiting and being waited upon…Jamaica is waiting to be discovered,

waiting for the tourist to come, and once they arrive, they can expect to be served, not unlike

how colonial elites were once waited upon. The servitude of the locals becomes a part of the

authentic experience tourists can expect when they visit.

74

Image: A white couple being served by a male butler at the Sandals Resort.

75

74 Gordon, 41. 75 Images sourced from the Sandals website, retrieved July 19, 2019.

46