5 minute read

Pranav Sood

Neon Tints and Love Footprints

by Kyle Jacobson

Advertisement

Shared meaning is reality’s chimera— multiple truths merged into something concrete. Very distinct and easily understood. But stare at it too long, ask too many questions, and it’ll be picked apart until interpretation uproots meaning from whatever plane of authenticity it found purchase in. Pranav Sood’s bright, captivating paintings initiate a conversation on love, but the more an individual attempts to determine precisely what’s taking place, the further they stray from their original impression.

“These paintings are very personal,” says Pranav. “They are autobiographical, but also universal because everybody experiences love.” Love itself has a unique purity when we let it happen without defining it. The more barriers we put up between when we are allowed to experience and share our feelings, the less genuine they feel. Recreating intimate moments through detailed patterns and an attractive Warhol-esque use of vivid color, Pranav captures the essence of what makes us want to replay our most-treasured memories over and over, putting feeling before detail.

How Pranav found his voice goes back to his childhood in India. “I started studying for art from a very young age. I think I was painting since kindergarten. Moving forward, I went to Chandigarh, it’s the capital for Punjab. I’m from Ludhiana, which is like two hours away from Chandigarh, where I went for studies in art school. I studied there for four years as an undergrad and learned many things. Went on tours to different parts of India to learn ancient skills of arts—traditional painting styles—to find their roots, like what Indian art is. In art school, they usually teach only the modern, the Western styles. I wanted to see what the Indian style was. So I learned those and started to find my own style.”

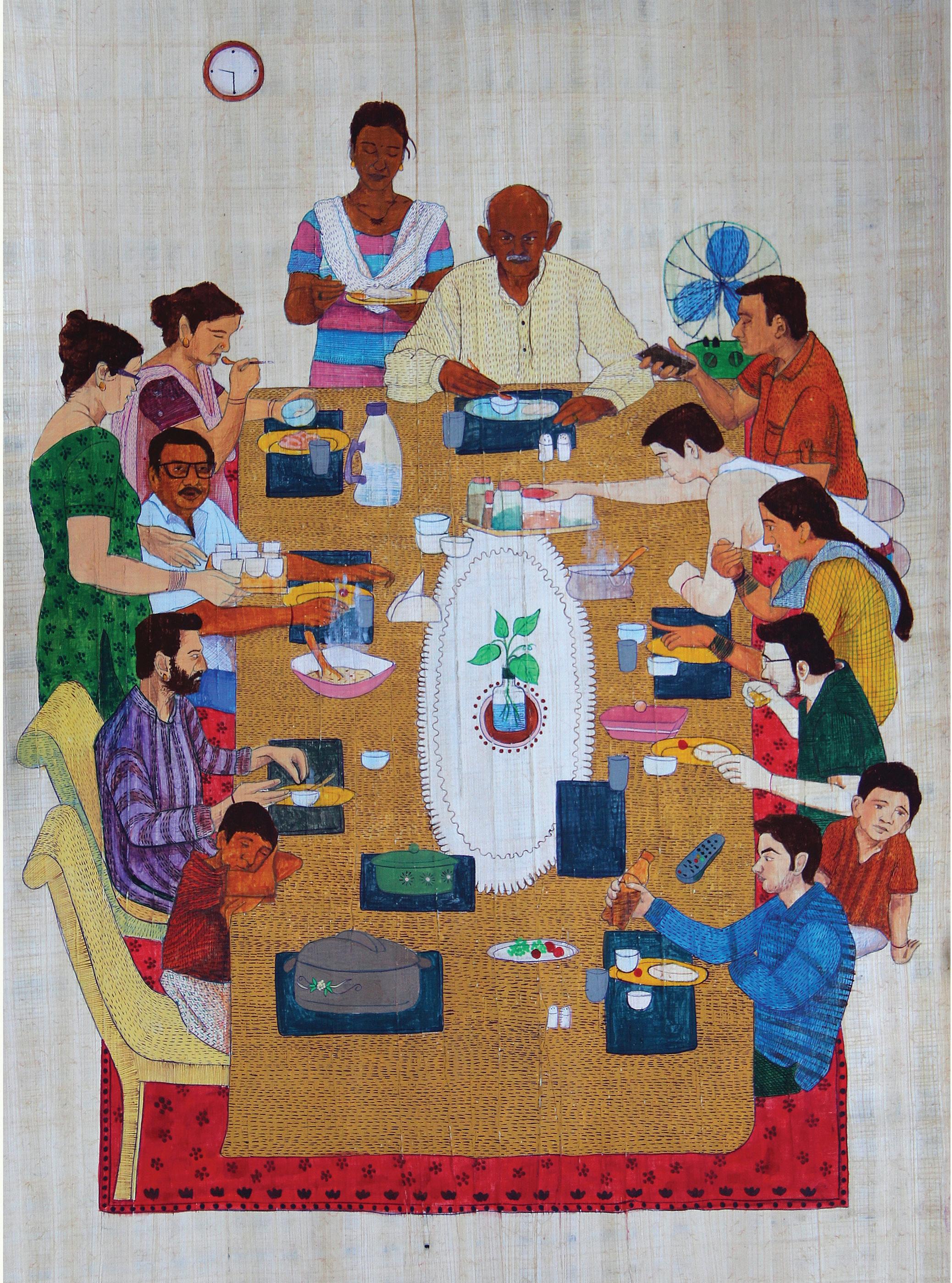

The evolution from Pranav’s early works is clear, almost mirroring the path of Picasso. His first body of paintings seek to capture reality for what it is. “In this, the people actually look like people. You can understand their age, and they have realistic features.” Over time, exaggerated shapes and static motions akin to hieroglyphics create something to be immediately interpreted. “They are more cartoon like, graphic; they have very simple features. ... When I started painting [Family Time], relatives or people used to come and say, ‘Who is your mother? Where are you? Who is this person?’ I never liked that. I wanted to make paintings that are universal. People can connect with it rather than trying to find connection with me. So I started finding a way to reduce the physical features and convey a message.” A message which is appropriately amplified by blending pop art and cubism.

Some paintings, like One for me, One for you, allow the audience to interrupt a moment in time ad infinitum. “In this painting, someone said they couldn’t understand if she’s inviting the boy or

saying no to the boy. So the boy came in with the beer, offering beer, like he’s on a date or approaching the girl, and the girl is either accepting it or just saying no. It’s on the perspective of the viewer what they understand from this.”

Much like abstract art, the paintings aren’t complete without an audience’s perspective. Pranav uses love as his muse, so it’s not surprising to find a range of metaphor in the pieces, from the foundational to the conceptual. The same style of tree, for example, is adorned with different fruit to present the idea of that type of fruit tree. It doesn’t have to remotely look like the real thing, just give a base representation of the idea.

Family Time

“I just try to think like a child—simple things. Any age group can enjoy and find different meanings. They can enter from anywhere and exit from anywhere. There are a million possibilities in the same image.”

But the metaphors he uses for love, whether it be familial, adventurous, or dreamlike, seek to distinguish what is real and what is forced. You and Only You gives us parties and lovemaking—love that may last for only a moment and is all the richer for it. That same richness is found in The Day Without You, where it seems a person is describing their day without the person they care about. “I tried to find a contemporary version of

ONE FOR ME, ONE FOR YOU

[Indian miniature painting] with a more autobiographical or universal sense. In Indian miniatures, they talk about gods and goddesses, but I wanted to talk about modern love. The love we actually see. I combined it with pointillism and Byzantine art. All the history classes I took, I just combined what I loved.

“I’m trying to bring in the societal pressure couples face. Like in India, couples don’t show affection to each other or love to each other in public, and people usually stare at them or just feel awkward. That makes it very difficult to go out. Even holding hands or kissing outside feels very awkward. When I came to U.S., I realized it’s very common, and it’s easy. Nobody’s judging or making an awkward environment. I felt like I needed to create those moments and show what is different in India.”

Interestingly enough, Pranav shows how alike love is in our cultures by contrasting those differences. Love isn’t just a shared meaning; it’s a shared concept. The ability to feel, to share compassion, is where his work ties into his audience. “I try to find philosophies, like couple’s philosophies and humor. Things people make jokes about or talk about and just laugh. It’s very universal. I remember one time I was talking to somebody, and there was a girl who said, ‘These two are like me and my

husband.’” This was her take without applying language to it—without dissecting the moment.

The mosaic quality of the background, almost like intricate kumiko woodwork, and the events taking place give audiences reason to reinterpret Pranav’s paintings upon each viewing. It speaks to a thread woven throughout the works: that though who we are will change over time, love’s potency doesn’t fade—it just takes on new forms.

Kyle Jacobson is a copy editor for Madison Essentials, and a writer and beer enthusiast (sometimes all at once) living in Dane County.

Kyle Jacobson

Photograph by Barbara Wilson