4 minute read

AN IDEAL WORLD

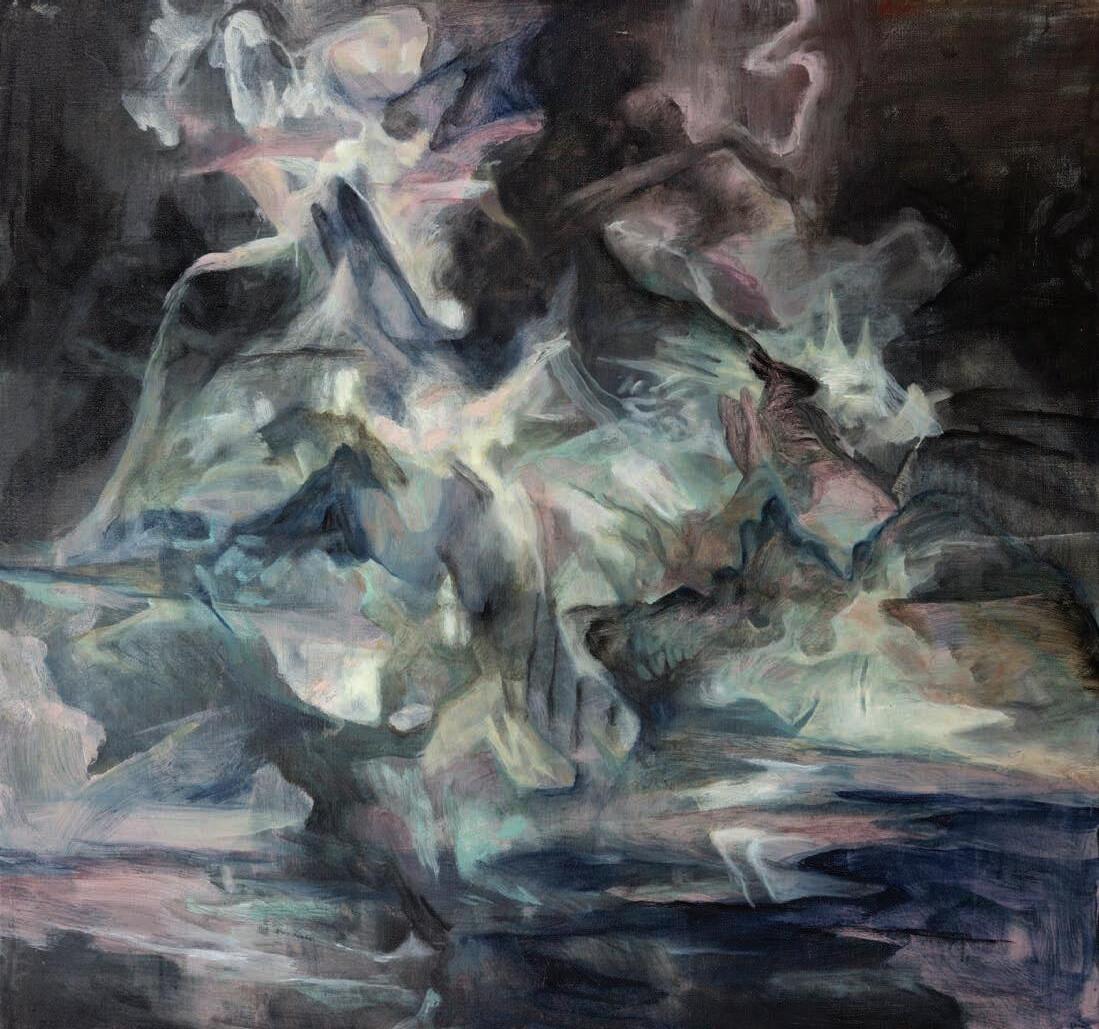

Jordan Grant’s paintings appear to reside somewhere between being vague transient spaces and changing, sometimes dynamic locations. They are formed through abstract gestures and stylized mannered fragments as pure material objects, manually worked with a sense of searching for something concrete, but where the tangible remains elusive. It is almost as though what has been formed in these paintings was first conceived through the misrecognition of something fleeting, caught in movement; something that may never have existed, something from the back of one’s mind.

The imagery in Jordan’s works forms through gestural sweeps of paint and accumulations of shapes that are informed by observations or recollections of half-remembered things: landscapes, plants, spaces, wind and water, along with fragmentary but intimate depictions of the human body, naked and held within something. These works form into a confluence of incomplete, fleeting and half known associations and forgotten memories. Here it might be relevant to consider Sigmund Freud’s idea of the emergence of the subconscious, forgetfulness, and ‘the return of the repressed’, a condition where that which has been repressed subconsciously must eventually in some form or other, be expressed1.

Interestingly, in conjuring an ‘unknown place’, as Jordan does in his paintings, one must work through what is known. Many forms of abstraction evolve in this way, where the artist may be founding their work in what they know, but attempting to express something that they may not quite know how to represent or to find. A painting of this type can be seen as the making or forming of an alternate place, providing us with an encounter involving familiar elements within an unknown space.

Through their layering Jordan’s paintings evoke a sense of embedding and revealing, forgetting and remembering, where the sum may be greater than the parts. And this memory and forgetfulness appears as a type of terrain, conjuring places where one is aware of shifting within time and through time. Therefore a feature of these works is that they chart transformation and time, along with recollection, arousing feelings of not really being ‘grounded’ in anything, and reminding us that at times within our minds, we exist within a type of indeterminate transitional vagueness and abstraction.

But equally Jordan’s works convey an external place, the unstable exterior world of today.

In our connected world, where we are only ever a click away from knowledge (where people dream of going ‘off grid’), we exist within a fluctuating network of infinite language, images and signs, a vast sea of information as fluid and profoundly deep as it is wide. Our world and our presence can only be described as multifarious. Jordan’s paintings equally relay things about our world and our times, where we often have to gain access to an understanding of things through a range of vantages, none of which might be declared as singularly authoritative; where one meaning may quite possibly be as relevant as another.

Cultural theorist Françoise Vergès2 confirms this by describing our circumstances today as being informed by diverse visions, somewhat like a projected palimpsest3, which despite being the product of erasures and re-writings also demands constant revision of the central ideas that underpin it. Today we are encouraged to replace ideas or thoughts that we may take for granted with new foundations. Vergès suggests that our times, marked by change and shifting vantages form as a type of cumulative palimpsest, where ghosts are evoked, where we do not fill gaps or mask disappearances, where absences may be visible, forming a web of layers that make it difficult to understand what we are held within. The character of our time is formed through swift, and ceaselessly layered accumulations of events, information and histories that seem to instantly become submerged and replaced, conjuring the notion that perhaps, as Vergès again indicates, we should acknowledge a symptom of these times being, again a type of forgetfulness, in order that we cope with our multifarious existence.

So while these ideas about our times could make it difficult to even know how to think about things, how to even grasp what the world is in the face of so much information and communication, it does form a rich and poetic space for fiction and the imagination, a terrain where nothing can really be predicated on one central truth or reality, where our sense of actuality has become a beverage of fragmentary perceptions. Coupled with this, our brains appear to process by remembering and forgetting through a cycle or loop that takes us through our lives, and in this we discard things that are no longer useful to us, while we hang on to others. We sift and sort through layers and our memories come to us, factually, as fragments, while memories also often coexist within atemporal framings, shunning linear realities.

Many of the places we go to in contemporary art these days are disembodied psychological spaces rather than physical places. However in the instance of Jordan’s paintings, while we encounter imagery that suggests our interior world, our minds, these works are also coupled with associations of the world we live in, a place of change, confusion and layering that nevertheless may be strangely beautiful within itself. Rather than representation, Jordan’s paintings are focused more on interpretation and feeling, evoking an almost ungraspable vision of ourselves and the world

I learned in my childhood that a work of fiction is not necessarily enclosed within the mind of its author but extends on its far sides into little known territory4 .

Peter Westwood

Peter Westwood is an artist, writer and curator based in Melbourne, and a Senior Lecturer in the School of Art at RMIT University

Notes

Freud, Sigmund. The Psychopathology of Everyday Life, trans A.A. Brill (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1914). Online: www.bartleby.com/284 Vergès, Françoise. Like a Riot: The Politics of Forgetfulness, Relearning the South and The Island of Dr Moreau, South Magazine Documenta 14, 2016

3. 4..

A palimpsest is generally an old document that has been through a process of erasure, where one set of writings has been replaced with new writing. Therefore the entire information that has occurred in the document is never available, while the document usually evokes diverse layers or aspects beneath the surface.

Murnane, Gerald. Barley Patch. Artamon NSW: Giramondo Publishing, 2009. p68

Nocturne I 2016

Oil on linen 122 x 117 cm

Opposite: Nocturne II 2016

Oil and cyanotype on canvas 168 x 148 cm

“A work is never completed except by some accident such as weariness, satisfaction, the need to deliver, or death: for, in relation to who or what is making it it can only be one stage in a series of inner transformations.”

Paul Valery 2

“The necessary painting is a painting that could have failed. It grew uniquely and its final shape is one that the painter could not have foreseen at the beginning. And because it was discovered in good faith rather than predetermined and merely executed, its appearance registers, for both the painter and the viewer, as a surprise and something of a gift.”