JULIE FRAGAR BIO GRAPH

Curated by Jonathan McBurniePublished on the occasion of Julie Fragar / Biograph

Publisher

Galleries, Townsville City Council

PO Box 1268, Townsville QLD 4810

Australia galleries@townsville.qld.gov.au

©Galleries, Townsville City Council, and the respective artists and/or authors 2022

ISBN: 978-0-949461-58-2

Artist

Julie Fragar

Curator

Jonathan McBurnie

Publication and Design Development

Townsville City Council

Galleries Team

Jane Scott Galleries Director

Contributing Authors

Jonathan McBurnie

Rosemary Hawker and Elisabeth Findlay

Francis E Parker

Artwork Documentation

Carl Warner

Ashley Barber, courtesy Sarah Cottier Gallery, Sydney Organised by Townsville City Galleries

Julie Fragar is represented by Sarah Cottier Gallery, Sydney sarahcottiergallery.com

Jo Lankester Senior Exhibitions and Collections Officer

Sascha Millard Collection Management Officer

Veerle Janssens Collection Registration Officer

Leo Valero Exhibitions Officer

Michael Favot Exhibitions Assistant

Chloe Lindo Curatorial Assistant

Rachel Cunningham Senior Education and Programs Officer

Jonathan Brown Education and Programs Officer

Ashleigh Peters Education and Programs Officer

Tanya Tanner Senior Public Art Officer

Caitlin Dobson Public Art Officer

Anja Bremermann Gallery Assistant

Katya Venter Gallery Assistant

Zoe Seitis Gallery Assistant

Maddie Macallister Gallery Assistant

Rhiannon Mitchard Gallery Assistant

Deanna Nash Team Leader Business Support

Sue Drummond Business Support Officer

Christine Teunon Business Support Officer

Abbigail Thomas Business Support Officer

Emma Hanson Business Support Officer

Perc Tucker Regional Gallery

Cnr Denham and Flinders St

Townsville QLD 4810

Tue – Fri: 10am – 5pm

Sat - Sun: 10am - 1pm

07 4727 9011

galleries@townsville.qld.gov.au whatson.townsville.qld.gov.au Townsville City Galleries TownsvilleCityGalleries

Townsville City Council acknowledges the Wulgurukaba of Gurambilbarra and Yunbenun, Bindal, Gugu Badhun and Nywaigi as the Traditional Owners of this land. We pay our respects to their cultures, their ancestors, and their Elders – past and present – and all future generations.

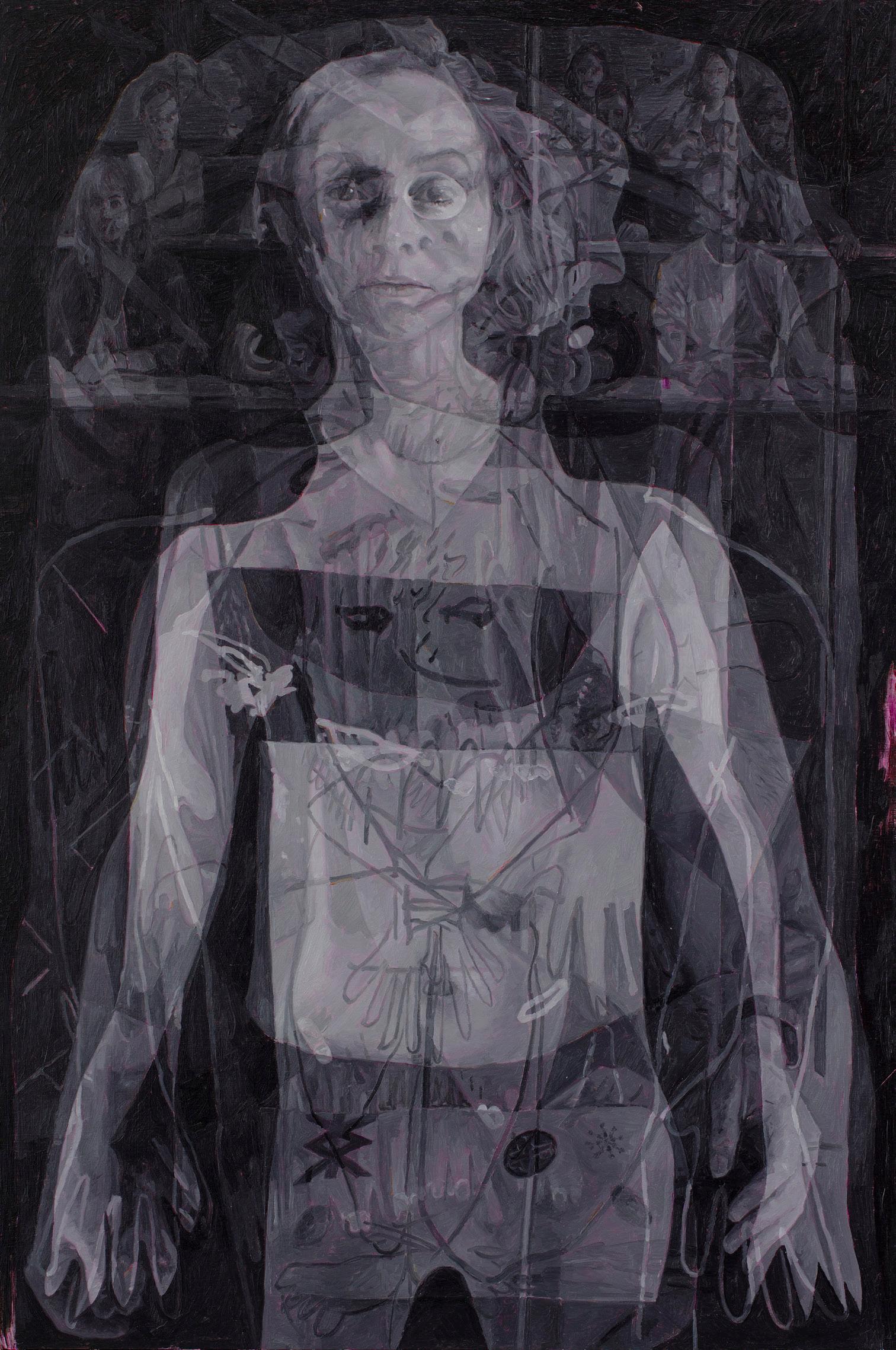

The Single Bed [detail] 2017 Oil on board, 135 x 100 cm Collection of Griffith University Art Museum. Purchased 2017.

Perc Tucker Regional Gallery

2 December 2022 – 12 February 2023

University of the Sunshine Coast Art Gallery

1 March – 28 May 2023

Tweed Regional Gallery & Margaret Olley Centre

9 June – 27 August 2023

Rockhampton Museum of Art

8 December 2023 – 3 March 2024

Julie Fragar / Biograph is a travelling exhibition produced by Townsville City Galleries, and exhibited at:ACKNOW LEDGEMENT OF LENDERS

Julie Fragar: Biograph wouldn’t be possible without the generosity of many institutions and collectors who have loaned works. Assembling the number of historical works included in this survey has required a great deal of time and effort, with many forming a special part of private collections and several unseen since their initial exhibition. We greatly appreciate the support of lenders and those who helped in facilitating this exhibition.

A huge thank you to Sarah Cottier Gallery, Sydney (Sarah Cottier, Ashley Barber and James Gatt) who have been representing Julie for over a decade, and were instrumental in securing crucial loans. Sarah has loaned works from the gallery and her own personal collection.

Thank you to Bruce Heiser Projects. Bruce represented Julie in Brisbane for seven years, and continues to be a keen supporter. He secured several key works for this exhibition from supportive patrons, and loaned from his own collection, also.

Thank you to Townsville City Galleries for your continued dedication to this project despite scheduling difficulties caused by COVID-19 and the flood before that. Your passion for excellence continues to benefit artists and art lovers alike.

Thank you to the many institutions who kindly loaned works, and for the great enthusiasm in supporting this exhibition. These include Devonport Regional Gallery, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Pine Rivers Regional Gallery, Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art, Griffith University, University of Queensland Art Museum, HOTA, Monash University, Art Gallery of South Australia, Rockhampton Museum of Art, and the Cruthers Collection, associated with Sheila: A Foundation for Women in Visual Art, administered by the University of Western Australia.

There are also those who have generously loaned works from private collections. They are acknowledged in this publication either by name or as ‘private collection’, according to their preference.

Finally, a warm thank you to Julie’s family and friends who have made this exhibition everything it could be.

ESSAY ONE POLYGRAPH

Written by Jonathan McBurnie I: FlagylBiograph is the first survey of the work of Julie Fragar. There are many who might consider Fragar’s work overtly autobiographical, and certainly there is an argument for that. However, upon closer consideration, it becomes clear that the artist’s work is as much biographical as autobiographical, often at the same time. Playing with the complex intersubjective relationships implicit in both fields is a key tenet of the artist’s work, and the basis for this exhibition.

While particularly in the early stages of her artistic career, Fragar did indeed use photographs of herself and loved ones as the basis for many of her paintings, this practice and perspective did not take long to grow into a more complex meditation upon the artist’s relationship with the subject—Fragar’s work could only occasionally be considered portraiture— and the nature of the image itself. Further, the goal of autobiography is to reveal a particular perspective or truth about the author, whereas biography’s mission is much more specific to the portrayal of a subject other than the author. Fragar approaches her subject matter, including the subject-matter of her own life, as a biographer, taking a comparatively arm’s length approach to firsthand experience. Part of what makes her body of work so fascinating is its tendency to both offer up something that appears in the first instance to be almost diaristic, only to obfuscate ‘authentic’ details. This reflexive technique has in recent years extended to incorporate

narratives that stand quite outside the artist’s immediate experience, referring to human lives more broadly—our lived experiences of the legal system or hospitals for example. Yet even in these more socially-engaged works, Fragar’s works continue to double back to the individual and subjective nature of all experience and her self-conscious role as the artist, imbricating the personal by way of collaged imagery.

Artists are constantly messing with biography and autobiography. Visual art, film and literature is littered with biographies, autobiographies, and thinly veiled versions of both.

Chaim Potok’s My Name is Asher Lev (1972) is the story of a gifted artist born into a family of observant Hasidic Jews, and the difficulties of participating in the conflicting traditions of art and Judaism. Lev’s experiences draw heavily from the author’s own as a writer and visual artist, as well as his own experiences within the Jewish faith (Potok was himself ordained as a rabbi in 1954). The novel even described and referred to key paintings that the author himself had created.

Charlie Kaufman’s neurotic playwright Caden Cotard (of Synecdoche, New York (2008)) turns his fraught personal life into fodder for his latest play, after being awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, giving him the means to pursue his own artistic dreams. As the play (which begins at the point of his estrangement of his wife and daughter) grows in metaphysical scale as

it begins to spiral out of control. Rather than resisting, Cotard uses the creation of the play itself as further fodder, enlisting understudies for key cast members (including himself) to follow them through the creation of the play, and in the process, their waking lives. Reality blurs with fiction, the understudies soon have their own understudies, and Cotard eventually cedes all directorial power to the understudy of his understudy, choosing to follow instructions given to him through an earpiece. The play is, never performed to an audience, and Cotard eventually finds himself alone and abandoned in the ruins of the gargantuan set; the life of Cotard the man having been entirely cannibalised by the fiction of Cotard ‘the artist’.

Vasari’s The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects (1550), considered by many to be the first work of what we now know as art history, contained many biographical sketches of the great artists of the renaissance that are not strictly accurate. As Vasari’s own biographers, Ingrid Rowland and Noah Charney note, he would frequently refer to unnamed sources, and even choose to include incorrect information and that also had profound effects on the real lives of the artists. i

Helen Garner is perhaps Fragar’s most direct literary analogue, both in terms of the artist using their own life to draw from, and in diverging from objective truths by making small edits which amount to something more complicated than a straight autobiography. Her novels, particularly Monkey Grip (1977), The Children’s Bach (1984) and the Spare Room (2008) are full of such edits, with character sketches so vivid as to be difficult to accept as fiction. Even her diaries, which currently number three volumes, have been published, are not straight autobiography, but rather sketches of moments or people, or notes and observations. Though a generation apart, both Garner and Fragar have been unapologetic in their choice of often domestic subject matter in their early careers, creating frank and often

unsentimental depictions of motherhood, relationships and the struggle of artistic pursuits. While both have gradually waded into more ambiguous and challenging material, in both a technical and artistic sense, both Fragar and Garner often circle back to these themes, grounding their practices in their daily lives. Such practices are not always comfortable. Life in the studio is not separate from the rest of the artist’s life, and one will inevitably influence the other. It is in this betweenspace that Fragar’s work truly captures the artist’s complicit position within their own life. In recent years, this has become an increasingly difficult rod for the artist’s back, first in the gradual stiffening toward or avoidance of the camera of the artist, and then by the more personal complications arising from painting the faces of others. This is a particularly difficult aspect to work around, both in the context of this essay, the exhibition, and the artist’s practice more broadly. Several works, many of which I consider key works, have had to be removed as a result, and this is reflected also throughout this text. In its fashion, this editing of the survey and its materials reflects the very kernel of what many of Fragar’s works actively explore, in terms of self-editing, obfuscation and biography. Fortunately, Fragar’s practice had already pivoted away from the overt use of family photos toward a more composed and arranged process of image making, but the removal of specific works due to unforeseen twists of biographical fate add another compelling layer to the complexities of such a human-centred practice.

II: Meet Me at an Arm’s Length

Given the literary and philosophical allusions present in many of Fragar’s works, perhaps it is no surprise that literature is a particularly incisive access point into Fragar’s practice. There is a particular treatment of the self that the artist is careful to present; guilelessness is a rare commodity, particularly in the more internal arts of writing and painting. As David Malouf, himself a writer of no

small understanding of the way we present different selves through our art, explains, ‘… there’s a gap, a mysterious and sometimes disturbing one, between the writer’s daily self, his walking and talking self … and the self that gets the writing done’.ii Unlike many of her contemporaries whose concerns rarely cut deeper than the surface they produce, and whose use of photography goes no further than the desire to mimic its sheen, Fragar’s work faces head on the specificity of each artistic choice, the specificity of each medium, subject and manner of articulation; Fragar has a conscious relationship with photography and literature but is categorically a painter.

On a superficial level, Fragar is a devastatingly proficient technician, but this proficiency is not limited to anything as narrow as virtuosity; she is adept in terms of communicating emotion, manipulating narrative, and more generally stalling and subverting all of the very worst conventions we have come to expect from contemporary painting (unselfconscious navel gazing, painting-as-therapy, or the vulgar aesthetics of wealth, for example). Fragar manages to achieve a balance of painterly accomplishment, intense sincerity, and intellectual inquiry in her work, constantly manipulating the metaphysics between painter and subject. The paintings, so often the beneficiary of subtle artistic modifications and a deep and abiding love for its subjects, occasionally comes off as deadpan or bathetic, but never cheap or vulgar. One is left with an impression that these are paintings of real people, even in their most constructed states. Fragar’s subjects are afforded a quiet dignity, and some truly sublime moments are found in a world of endless chromatic, sometimes chaotic, variation.

It is important to stipulate here that, while she has (technically) painted some portraits, Fragar’s work does not sit neatly into the paradigm of portraiture; in fact, in many ways, her work explodes the entire notion of the portrait, in that it admits the fabrication, the pose, the construction, and toys with these notions to achieve her own

(far more interesting) ends. To call Fragar a portraitist would be reductive. One could argue that every artist’s presence can be found in their work, but few volunteer their presence on such a conditional and intimated contract as Fragar. The very title of this exhibition, Biograph, was chosen because it alludes to the complex associations at work within Fragar’s practice. ‘Biography’ would be far too literal in Fragar’s case, and ‘Autobiography’—at least in the generic sense—is a stretch. However, as a verb, as in ‘to biograph’, we get a little closer to the way Fragar works. Details are selected, truths are edited by virtue of deletion or overlook, stand-ins and ciphers are found.

The works comprising Biograph urge the viewer to consider Fragar’s work as constantly dualistic, and deliberately complicated in its intention. None of her works could be considered completely autobiographical, nor could they be taken to be completely fictional or fanciful. Each work operates quite comfortably in its own little world, deliberately resisting a clear reading from one to another. Narrative is ever-present, but only insofar as the viewer will bring their own set of presumptions with them. Even at their most particular, reading of Fragar’s images are complicated through details, subtle elements and manipulations that temper, subvert or direct the reading of the work. These complications often point to the image as a construct, effectively putting the painting between the viewer and the artist, highlighting the contingent nature of human exchange through images and through painting. Compare the artist’s placement of the self and other personal details in works such as Looking for D-Rection (2009), Ghost Skin (2012) and The Single Bed (2017) and you will find an evolving understanding of both picture making and life’s complexities. Language, especially painterly language is always faulty, always an approximation that will inevitably be misconstrued. And at the same time, sometimes we can experience a deeply felt intimate connection between artist, painting and viewer. Our desire

for connection and the impossibility of really understanding each other— perhaps especially through painting—is key to Fragar’s work. She uses that eternal conundrum as a problem to be thought about through painting. Some of her paintings pull us in, others push us away, some reveal or disguise and very often they do all these things at once.

Researching ahead of this exhibition, I found it incredibly appropriate that in her doctoral thesis, ostensibly about Marlene Dumas, Fragar delivers possibly the most articulate and insightful reading of her own practice to date. Virtually any passage can be considered in the context of Fragar’s own work, also very much concerned with autobiography—as a field of academic inquiry born from literature studies— and in doing so we get a much clearer understanding of the complexities at play within the autobiographical paradigm. Indeed Fragar deploys autobiography herself as a device both familiar and distancing; we are coaxed into a sense of familiarity through the universality of the family photograph, and yet Fragar’s artistic decisions are so often made to complicate our reading of the work, or indeed, her own relationship with the image itself. In doing so, Fragar has deliberately sidestepped what she terms a ‘stultifying formula’iii for her practice.

Fragar outlines the changes in thinking around literary autobiography, particularly in the post structuralist wake of Barthes and Derrida, however a literary theory approach to the artist’s work will only get us so far, even considering her frequent use of text. Imbricated with her approach to autobiography, which is a rich, metaphysical and sometimes playful artistic sandpit to explore, is Fragar’s attraction to the physicality of paint, and the idea of painting, itself a mucky, sensuous post-structuralist idiom with a long history. Together, these two theoretical approaches—the autobiographical and the painterly— congeal into a surface every bit as chunky, viscous and sleek as Fragar’s own use of paint.

In specifying the personal anchor points of Fragar’s ‘authentic’ authorial voice, we describe the tantalizing possibilities of manipulating the preconceptions of the works’ viewers; Fragar does so with a devastating and emotive impact. I would argue that any kind of dilemma of autobiography stems from the fact that even the most honest author will omit, obscure and overlook aspects of themselves of which they are either unaware or that they choose not to share or disclose. It is in this way that Fragar’s work embodies the complicated slippage between the art and the self.

Biograph, as a survey exhibition, avoids a straight chronological reassemblage of Fragar’s artistic career. Instead, it is presented as a cohesive body of work, highlighting the recurring concerns and fascinations of the artist that orbit her practice. To present this particular artist’s work chronologically would be interesting in terms of technical development (which always seems to be racing), but it is Fragar’s sustained interrogation of image making and the indivisible complexities of life within and without the studio which has remained unerring despite a couple of periods of conscious disintegration and reconstitution, that unifies her body of work.

III: Wassily Chair

Even Fragar’s earliest work makes a statement in terms of self-referential and constructed imagery. Wassily Chair (1998) is a self-portrait of the artist, sitting in Marcel Breuer’s famous titular chair in front of a TV and VCR setup, watching pornography. Already, Fragar was exploring a set of variables that would set the terms for artistic exploration for years to come; carefully selective and potentially (though not certainly) posed photographic reference, chromatic execution, selfportraiture, self-reflexivity, and art within art. Fragar would become more heavily invested in the use of family photos in parallel with the infancy of her children.

Right from the start, such references were carefully selected for their pictorial qualities, or simply for what would make a good painting. The first five years of the twenty-first century saw Fragar evolve from a slick photorealism (Wassily Chair and Flagyl (both 2001)) into a confident, fleshy painterliness (note Fidel’s #2 (2005), only four years later).

While developing a highly sensitive use of colour, Fragar began making occasional forays into the disruption of the picture plane with additional layers. These disruptions of the picture plane mean the painting cannot be read from any singular vantage point, thereby demanding different perspectival considerations. Over the years, Fragar would adopt different pictorial strategies, but the goal of disruption was always the same. Works seemingly composed the way one might ‘draw’ into a steamed-up bathroom mirror, the finger lines cutting through to reveal the image beneath, and not dissimilar to ‘scribbling’ with the erase tool on Microsoft Paint or Adobe Photoshop but preceding the artist’s use of that technology. The entire effect is one of multiple images welded into a new visual whole.

But even during these years of carving out artistic territory, the artist was developing a practice of composite images, by way of selection. There is a sense of self-curation to the way ‘legitimate’ family photographs are painted side by side with similar images that have been posed. Such a distinction may seem minor, but in terms of impact, this is significant, as it effectively co-opts two of the artist’s strongest instincts, the found photo (‘real’) and the posed photo as source imagery (fictional), combined as a unified whole. Each subsequent series of work (Fragar works almost solely in series), would be built on the bedrock of imagery (found, posed, or both) complicated through various means. It is during this period (2008-2010) that Fragar truly began to find a unique artistic voice.

IV: Guarded

While exhibitions before the 2006-8 period included many engaging and accomplished works it is during these years that Fragar’s interests—in art history, in human experience and perhaps most importantly, in visual perception—seem to increase in technical and theoretical heft. Arthistorical references began to appear more frequently in exhibitions (particularly Man (2007), Optimism (2008) and Liar (2008), at Peloton, QAGOMA and Sarah Cottier Gallery, respectively). These art historical works, combined with Fragar’s more expected fare, loaded the exhibitions with some timely questions of gender politics, the role of the artist and the hierarchies of the art world, while simultaneously undermining at the self-seriousness of it all (Fragar’s ‘reclining’ series from Optimism, exhibited on a searing neon green wall, was particularly wonderful in its careful and elegiac silliness; reclining figures ‘propped up’ by the composition of the paintings, all of which rest at the feet of their historical father of Realist painting, Gustave Courbet, himself a notorious artistic trickster, and a painter of no small technical firepower).

It is at this time that the selection of source photographs becomes more complex. Personal photographs were still sometimes used as raw matter for paintings, however there were more staged reference images employed and a deliberate distancing of the images through the cutting up of photographs, which are subsequently integrated with other source images. These works, despite being flattened by the picture plane, incorporated a perceptual depth

within its own physical parameters. While Fragar had experimented with collage as a disruptive compositional agent before, the 2009 -2010 period saw a proliferation of these works. Many of these were exhibited in Meet Me At An Arm’s Length (2010, Heiser Gallery, Brisbane), and mark a significant move away from paintings of captured, photographed moments. In part, this is an inevitable evolution of the artist’s practice, a deployment of visual challenges, selfimposed in order to find new and exciting approaches to working and thinking. It is also a response to the complication of Fragar’s use of personal photographic referents; with the success of her artistic practice comes the reconciliation of her models’ responses to finished works, and by that point the impossibility of taking a personal photograph unselfconsciously.iv It is also around this time that the imitators (there are many) began to appear. Something had to be done to overcome these obstacles without compromising the strongest aspects of the work.

These years of growth also saw the expansion and heightened importance of text paintings. Usually devoid of punctuation or even spacing between words. Fragar’s text works are fascinating in their relationship to non-text works. Almost every series the artist has made comprises of at least one text work, and the link between text works and non-text works is not always explicit. While on occasion a text work can form a cornerstone or throughline for the series, or even between series (the later text work, Father Goes Mad (2014) unintentionally served such a role, though with punctuation and spacing), this is rare. More often, text works serve to underscore a series, offering a another possible language in service to the same theme. With their lack of punctuation and spacing, these works can appear deadpan, but are often the most directly autobiographical. Operating on a different textual level than Fragar’s figurative works, the text paintings serve as an ongoing counterpoint, a way for the artist to stand back from the rigour involved with working in series, and

commentate the series in a conscious, self-reflexive, and often self-critical light, breaking the narrative kayfabe of the series. These are often put to work as a distancing device in tandem with particularly personal subjects, but very occasionally, disappear altogether, in a space of sincerity and emotional openness. ‘Sometimes I think about these as giving over the picture to the mind of the viewer’, Fragar says in retrospect. When compared to previous works, they are at once invitingly universal and guardedly personal.

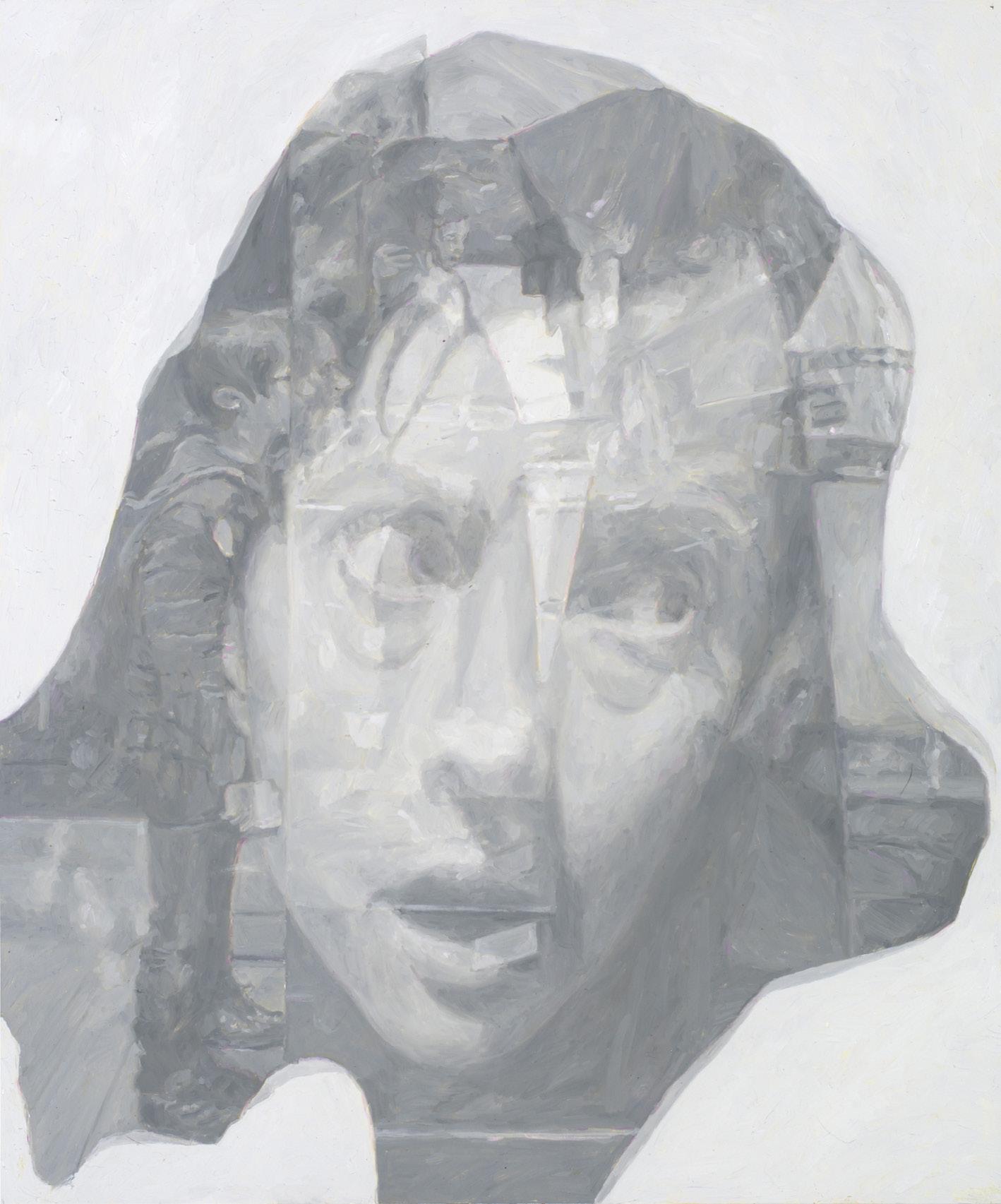

IV: Poking the Ghost Skin

By 2012, the collage-based works were beginning to give way to Fragar’s layered works (Ghost Skin, taken from the name of one of these series, seems an entirely appropriate designation) that, while constructed and executed differently, achieve a similar goal. That is, to deliberately distance the viewer from the source image, and thus the artist. The primary distinctions between the collaged (solid images combined) and layered (transparent overlaying allowed through the use of Photoshop) works are both formal and perceptual. Fragar’s collaged works of this time typically favour angular, geometric cuts. These are then reassembled with additional imagery, most often a central image placed behind the collaged segments. These hybrid compositions are ‘flattened’ through the painting process, and geometric forms can easily serve to expose or obscure key visual elements. Comprised of sections of three images Kind of Woman (2010) is one of the more ambitious and effective of these works. Two different photographs of the artist (one close up, eyes closed, mouth slightly open, the other possibly doing a push-up, eyes staring down the barrel of the camera) are cut into jagged triangles grounded by the border of the image, cutting in across a photograph of a museum scene, with elaborate walls, an archway, statues and vitrines. It is flesh that coheres the three images; the yellow-white marble of the statues, sensuous in their female

form and drapery, the artist’s sinewy, couperose arms, and the warm darkness of the closeup, all charge the image with an intense and complicated eroticism. The jagged collage forms slash across the picture plane, simultaneously disruptive and obscurant, yet somehow resolving the image through pictorial discord.

In contrast to the collage-based works, Fragar’s layered works breathe in unison, and can obscure in plain sight, with images digitally layered atop each other. This presents yet another technical challenge to the artist, who must now negotiate painting one hybridised image, effectively weaving the images together on the single picture plane, rather than painting separate sections of the collaged works. Additionally, the layered works can be interpreted as another way of representing memory; or what Fragar has described as a kind of ‘psychological Realism’. While many may relate, in the context of memory, to the jagged edges and smashed-together images of the geometric collages (fragments of a memory, let’s say), the layered works provide an equally compelling argument for the representation of memory or visual as psychological experience. Unlike photographs, the visual imagination is intangible, and we have little control over the ways they manifest, develop, settle and evolve; certainly they are not static. Fragar’s layered works create the impression of multiple perspectives, locations and times, in a way imitating the mind’s collapsing of personal moments into an abstracted narrative that we can access via particular, linear moments, or in unison as a kind of mental visual stew. These kinds of self-imposed compositional structures, while adopted to explore visual perception, have also kept Fragar on a track of continual studio evolution, tackling increasingly ambitious compositions. The employment of this technique began in earnest in the period leading up to Fragar’s next exhibition, Marathon Boxing and Dog Fights (2013, Sarah Cottier Gallery), which constituted an artistic break in more ways than one.

III: Not Your Fault

Marathon Boxing and Dog Fights was an intense body of work; many of the works of this period were responses to loss and emotional upheaval, as well as the rigor and focus of postgraduate study coming to a close. In this way, her work eloquently articulates the dangers inherent in using one’s own life as a resource for creative work. While I do not wish venture into biographism, it is certainly notable in the artist’s departure from overtly personal imagery, as if the family snapshot were off limits for the moment (a moment which did end up lasting a number of years). Instead, Fragar consciously pivoted away from her wheelhouse, leaning into the layered works. In its harsh imagery and emotional rawness, Marathon Boxing was (and remains) Fragar’s most raggedly intense exhibition to date. Rather than relaying the visual reality of her life in concrete terms—Fragar notes that these paintings do not refer in any way to actual physical violence— instead she uses the images of fighting dogs and fatigued, punchdrunk boxers to create a visual parallel to the feeling of sheer emotional and physical exhaustion. Fragar has come to see this body of work as a turning point, a period where she began to shed some of the safety of dispassion and irony inculcated during her early art school experiences (contextualised by Post-Modern aesthetics of the 1990s) in favour of more sincere pathways.

Marathon Boxing featured several works that used layers, which compounded the muscular and sometimes bloody-minded imagery of this series, while maintaining a taut mystery. The irony of using predominantly found, layered imagery to explore emotions of an incredibly personal nature is tantalising, and by no means accidental, especially in contrast to the artist’s tendency to mine personal subjects and imagery in the studio process. While the series did include two bleak self-portraits, Stroke and Red Flag (both 2013), these were far from straight self-portraiture. The source images were

posed photographs of the artist herself, pallid, smoking, exhausted, despondent. One layer, over Stroke (2013), depicts the rude, muscular physique of a boxer. The other, which features an additional ghost skin of the artist in a different pose, also appears to overlaid with a boxer’s torso, as well as what appears to be some kind of fleshy striation, either a wound or rot. This ambiguity between skins (or skeins) creates a separation of forms physical, metaphorical and emotional, as in real life, an acknowledgement that there are circumstances in which lives are broken and will never be quite the same again. For an artist so reliant upon a personal visual lexicon, this step away from more direct autobiographical referencing was a tectonic shift.

IV: Off Sure Feet

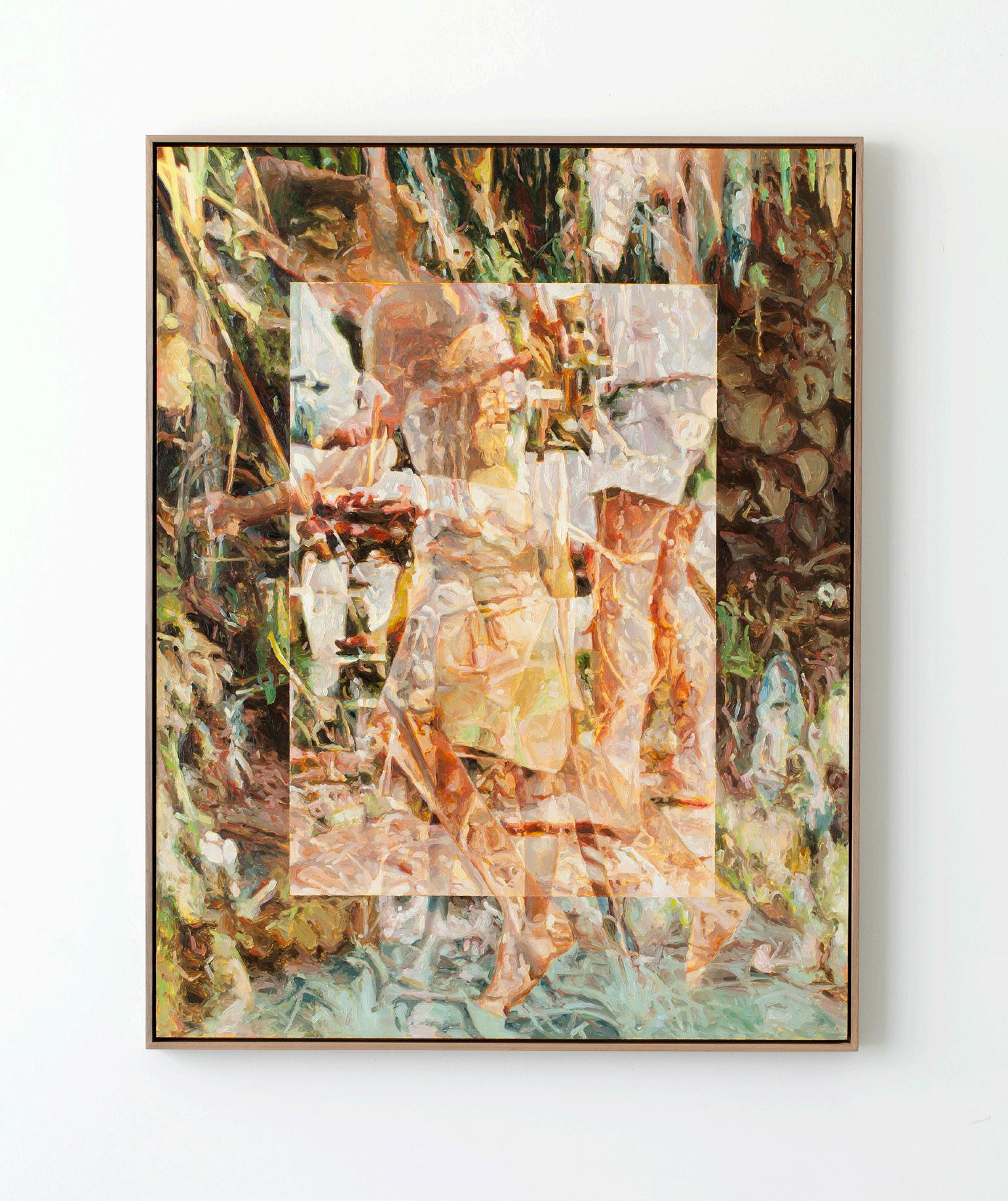

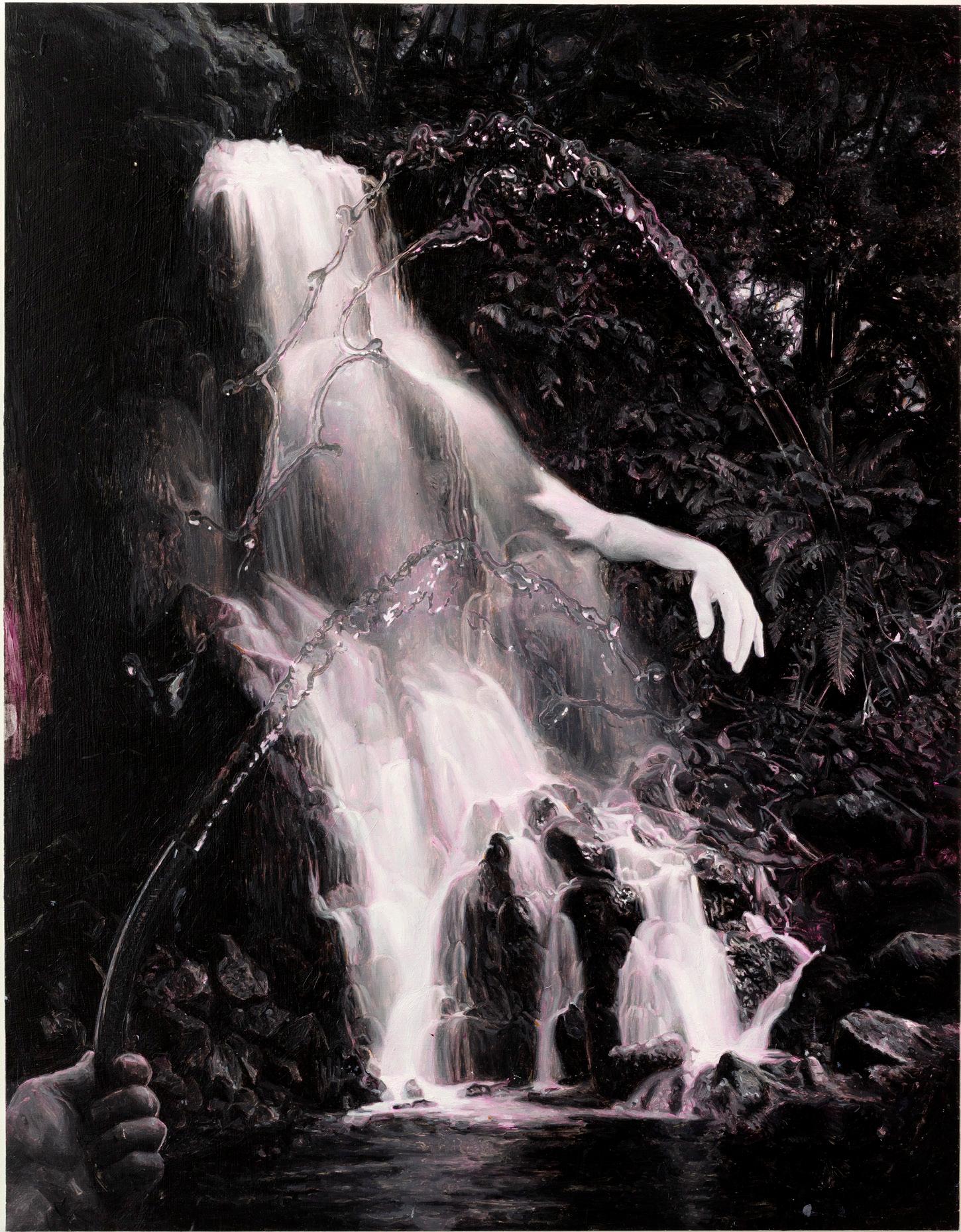

Fragar’s Antonio series that followed presented a new approach, pointedly biographical rather than autobiographical.

In New Paintings (2014, Sarah Cottier Gallery) Fragar stepped outside of her immediate experience, and even outside of her own time, exploring a fascinating family history, embodied by her ancestor, Antonio de Fraga. The fragmentary true story of Fragar’s ancestor, Antonio, is fascinating. At the age of twelve, the Azorean ancestor was packed onto a Californian whaling ship by his father, sending Antonio in search of better opportunities. Over a period of the following seven years, the vessel was twice shipwrecked, and Antonio, unlike the majority of his fellow crew, managed to survive and come to Australia. As Fragar explains, the narrative is incomplete, being made up of the few documents that remain, but what is known is that Antonio fled the island for fear of cannibalism, assisted by missionaries, eventually making his way to Australia. The incompleteness of Antonio’s backstory begged the artist to fill in certain details, particularly the grieving of his mother— Antonio would never manage to return to his parents— in the only text work of the exhibition. This work, entitled Father Takes Control, Mother Goes Mad (2014)

anchors the series, giving the exhibition both a kind of start and end point from which to approach the other works.

With her son Hugo as a stand-in for Antonio—who was also 12 years old when Fragar and her children visited the Azores— the paintings are made up of both transparent and collided images, hinting at possible real-world incidents and human relationships. Though focusing on the life of another in an altogether distant time and place, Fragar’s authorial presence permeates the work. By visually filling out the fragmented narrative of her forebear, Fragar engages with the slippery metaphysics of art and history. By interpreting and expanding upon Antonio’s story, the core of portraiture is made clear, that it can both link us in affective ways to subjects otherwise inaccessible in time or space and that will always, nevertheless, consist at best of a constructed half-truth delivered in the opaque language of painting. While Fragar continued to use photography as reference source, Antonio saw a conscious reconfiguration of her image making process, engaging with staging and composition in a much more active way, revealing scenes that we can hardly imagine, much less photograph, bringing together myth and reality. Such a folkloric story that still resonates in Fragar’s extended family provided a new opportunity to use the multi-faceted imagery to explore multiple subjects, perspectives and time periods in one work. These works also involved (and necessitated) the reconfiguration of biographical narrative into something fictional; a history from so long ago told through so many generations is undoubtedly embellished. In a sense, this series operates as a kind of palate cleanser, taking familiar aspects of Fragar’s artistic practice, rolling them together and extending them into a broader historical narrative spanning generations. The series was partially informed by an earlier trip to the Azores region of Portugal, where Fragar in a continuing familial search for Antonio’s

birth certificate, was unexpectedly reminded of the maximalist (yet nuanced) narrative power of Hieronymus Bosch. Bosch’s intense palette and densely packed worlds would be immediately applicable to Fragar’s work, particularly in compositional terms. Works like Cannibal Tom (2014) and The Whaling (2014) brought a deeper, tougher commitment to the layered works; no longer were these merely overlaid, but sections within sections began to emerge once again, in a sense incorporating the collage technique of the 2009-10 period back into the layers of Ghost Skin and Marathon Boxing. The results are compelling.

While Hugo again appeared prominently in the second series of Antonio works, the artist and her daughter Penelope also appeared. This series, while still engaging with Antonio’s biographical narrative also points to more timeless concerns. While Fragar means to make visible the invisible narrative of one aspect of patriarchal family history, the sense is less of direct biographical illustration and more of a performative visualization of an artist— who could be any artist or any person— going in search of a family member she never had the chance to meet and whose story provides a useful psychological thread back to Europe. That action of searching for our ancestors speaks beyond Fragar’s own preoccupation at that time and to the preoccupation of many (particularly Australian non-Indigenous) families of trying to conceptualise a meaningful genealogical identity stemming from the northern hemisphere.

I would posit that it was around this time—2011-2013—that the artist began to consider, and take advantage of, her iterative habits as an artist. With each series since the mid-2000s had come some form of development, a step forward, or pivot away from, the last series. It is during the second Antonio series, comprising of almost monochromes, that Fragar demonstrates the freedom to reintegrate and turn back to aspects of each series that had come before, which has the remarkable

effect of unifying her practice and drawing out specific elements which had been present in some sense the entire time.

V: Susan

After the intricate and comparably large scale metahistories of both Antonio series, Fragar took a step closer into her examination of her family history in her Susan Skelton series (Heiser Gallery, Brisbane, 2016). The grand gestures and scale of Antonio’s mythologising are replaced with circumspection, care, and a deep reserve of affection; again, stepping further away from the more critical (and occasionally sceptical) approach to the personal in earlier work of the 1990’s. The incomplete gaps so compelling in her ancestor’s nautical adventures are shrunk down to the space between people, places and memories of living subjects. Susan Fragar (nee Skelton), Fragar’s mother, would be the primary subject of this series of small, intimate works, which were all executed from family photos. These works are fascinating in their close and tender examination in contrast with the surprising narrative sprawl they seem to suggest; they are many narrative snapshots that construct a larger whole, coming together as a single portrait of one person. This is, to date, Fragar’s most pointed investigation of any one person beyond the artist herself, and she characterises this series as a conscious shift in her relationship with her mother, an attempt to both express her love for her —in many ways an exhibition for her mother— and also to deepen her understanding of and connection with Susan Fragar outside her role as mother. By now almost forty, Fragar described the palpable sense of passing time and changing familial roles as well as a deep sense of gratitude for what her mother had done, given that the artist herself now had experienced motherhood.

Importantly, these works provide an extreme example of Fragar’s development of simultaneously personal and socially or universally resonant work; there is a child/ mother relationship in these works that

has a melancholic universality. There are images of Skelton as a toddler (don’t dare miss the indignant petulance depicted in HSP Response (Susan Frances Skelton) (2016)), a child, and as a young woman, many of which seemingly drawn from photographs taken before the artist was born. The series’ stunning coda is Cell Division (Susan and Julie Fragar) (2016), a layered image depicting Skelton, holding a camera herself and looking somewhat pensive, and a second image of Skelton (by now a Fragar), smiling, with her arms around a young Julie. Almost inexplicably the series manages to sidestep nostalgia and tap into some incredibly raw emotion, delivered with significant impact that makes us all think about our relationship with our mothers. The works are also notable for being (at the time of writing) Fragar’s last foray into the unstaged punctum of family photograph.

the scope of known (or family historical) subjects, Fragar has sought to refer to the lives of others, in an ongoing project in painting human ontology. Having been commissioned by the Queensland State Parliament to paint the portrait of former (and first female) premier of Queensland Anna Bligh, Fragar’s attention has also turned toward lived experiences of larger institutions, such as the parliament, the court or the operating theatre. It is important to note that even within this comparatively socially focused work, that Fragar continues her reflection on her own experience of these organisations and particularly her role as the witnessing subject; the ethics of which has only become more pressing for Fragar as she better understands the power and responsibility of representing others.

VI:

The Elephant in the Room

The increased emphasis in the use of painting to both visualise and empathise with the subjectivity of another in order to speak to wider and shared human experience through painting was made clear in the Susan Skelton series and continued in subsequent work in an even more determined way. Reaching beyond

Fragar’s Trial Paintings (2017), as they came to be known, were based on a murder trial observed by Fragar at the Supreme Court of Queensland. These were once again small-scale and intimate, but unlike the Skelton works, were layered, leaning heavily into the forms made available by layered imagery. This may have been prudent on the artist’s part, another effort to partially obscure narrative, as these works were wholly inspired by the compelling narrative around a trial, which she was attending. Also like the Skelton works, the first Trial Paintings contained no staged reference images; these were gathered online through news coverage and even surreptitiously through social media. From the outside, this process may seem a somewhat dispassionate compared to working with personal photographs. While in some ways this is true—those involved in the trial were unknown to Fragar personally— it is also here that we see Fragar turn toward more focused strategies of observation. These processes develop their own type of relational intensity between artist, subject and viewer that, while slightly different in nature, are no less full of pathos in their result.

This interest in the lives of those who are entangled in the legal system led to a related, but very different second series in Next Witness (2018); one in which Fragar made a conscious effort not to focus on the salacious details of the trial narrative, but instead on the way institutional processes relate to or impact individual experiences. While Trial Paintings sifted dirt for detailed narrative morsels of a specific case, Fragar’s next series of works (centred on a second murder trial) was a much more overarching analysis of the court system itself. Thus began a period of analysis of human sensitivities managed inside broader social institutions (the legal system, the medical system, etc).

Throughout her practice, amidst a range of different concerns at different times—a practice that itself mimics the arc of a human life in which different life stages and experiences are more or less pressing or impactful at particular times— Fragar continues a process of what she describes as reflexive ‘checking in’ with occasional standalone self-portraits. Fragar’s There Goes the Floor: Self-Portrait 2020 (2020)

in many ways summarises the artist’s complicated relationship with selfportraiture and also with portraiture. An almost-monochrome with magenta and Old Holland Gold Lake peeping out of the gloom, the work is a piercing, defiant yet fragile depiction of the self. Rather than posed dead centre, which would suggest a mirror image, and therefore selfanalysis, the artist’s head faces toward the viewer’s right, yet her eyes remain, dark as they are, fixed on the viewer, silently contemplating, or even judging. One eye is almost completely engulfed in darkness, in which only the reflection from the iris and a hint of the white of the eye is painted, to remarkable effect. Her eyes could be heavy with tears, in contrast to the rest of the face, which wears a defiant expression. Only the wizened lines around the eyes and on the forehead provide any additional information in this remarkable work, and this is the information of years, etched with time, immovable and immutable.

Jonathan McBurnie, Curator

i. See Deborah Solomon, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/01/books/review/collector-of-livesgiorgio-vasari-biography-rowland-charney.html, retrieved 28/5/2022.

ii. David Malouf, ‘Writer and Reader’ in: The Writing Life, Sydney: Knopf, 2014: 3.

iii. From Fragar’s thesis Preface, vii (Kissing the Toad: Marlene Dumas and Autobiography, Griffith University, 2013).

iv. In a 2011 interview with Jonathan McBurnie, Fragar revealed the awkwardness of negotiating people’s responses to their depiction in work, and the difficulty therefore of taking ‘innocent’ photos, not necessarily with any intention of becoming subjects for paintings.

ESSAY TWO

ALL AT ONCE: JULIE FRAGAR’S PORTRAITS

Written by Rosemary Hawker and Elisabeth FindlayJulie Fragar has been painting portraits for more than two decades. While these paintings are often raw and confronting in their stark exposure of close relationships and fraught family history—and the extra weight of authentic experience this connection delivers is important to the works—they are not predicated on a straightforward pursuit of likeness nor identity. The artist is a variously reliable narrator, both through the unavoidable limitations of representation and the wilful manipulation of the autobiographic voice. Through a skilful staging of these compelling ambiguities, Fragar opens her works to an audience eager to recognise the experience of the sitter at the same time as something of a universal human condition. The strength of the works rests in their simultaneous communication of the image as a document grounded in the fact of lived experience and the generative capacity of the fictive that opens their interpretation to the viewer.

Portrait painters must always confront the problem of telling a story about their subject in a way that refers to a lifetime of events and relationships, and yet is communicated in a single bounded picture plane, all at once. This is not the same problem for literature or film, for example, where the material form of the medium is durational, where, to be very reductive, a word, a sentence follows another, a scene follows another, and a narrative is built and revealed in time and space. Painting’s problem is to communicate diachronic experience, that is, taking place across time, in a synchronic form, all at once.

In Fragar’s painting, we see a far more recursive approach to this problem than most portraits admit. The genre of History Painting, based as it was in communicating historical events such as battles and famous deaths, made this problem of expressing complex narratives within the space of a single image its own. Fragar’s specific strategies towards portraiture share something of the narrative ambition of that genre, most obviously in her Antonio series, 2016, but across all her work, she amplifies the problem of communicating narrative in painting even as she overcomes it. This type of struggle, it has been argued, is common to the diverse conceptions of medium across art history and a necessary condition for all art.i A problem must be overcome in order that a work be made and for it to succeed. So, this is a crucial recursiveness that rests on the materiality of medium and we argue it is central to Fragar’s success. As much as anything, her subject is painting itself, what it enables for the artist and how it resists her control, the problems the medium poses for representation and how making these visible constitutes the work in and of itself.

That is not to say that Fragar’s work is dryly conceptual, it is intense and unflinching in its scrutiny of the human psyche, especially when she turns her attention to her own experience. Her work is most often autobiograpical and she has painted many ruthlessly honest self-portraits. In these works, she regularly disrupts the conventions of self-portraiture, basing the painting on a photograph of her taken by someone else—she begins the painting not with how she sees herself

but rather how someone else has seen her, and through this process, alludes to an apparently close relationship outside the image, one that makes it possible but also problematic. She states, “Paintings, perhaps more than anything else, are literal sites for looking and being looked at, for human consciousnesses to visually ‘meet’ one another…”ii Fragar makes these acts of looking the overriding subject of many of the works in this exhibition, and the construction and interrogation of these sites of looking is apparent from her student work onwards.

image is not Fragar watching pornography but that she is being watched watching pornography in this indifferent way and that she chooses to paint this scene and include us in this complex cycle of looking generated in the apparent ordinariness of the original photographic moment

In Wassily Chair of 1998, Fragar matterof-factly watches pornography, with her seated figure seen from behind and the composition angled to include the television she looks to. While the image is in many ways calculated to show the artist’s technical virtuosity, the shimmering silk of her robe, the reflection of the metal in the chair, its tenor is of the domestic and mundane. Despite her looking at overtly sexualised imagery, any sense of eroticism is overtaken by the sharper details of everyday life: the extension cord running alongside the chair, the video cassettes with titles scrawled in thick texta, a user manual on top of the VCR player, the powerpoint just visible behind the crammed television unit. The Wassily Chair—an icon of design in any art school education—is brought into her domestic environment and reduced to a functional object in what is essentially a dispiriting milieu. She says, “Wassily Chair sets up a kind of tug-of-war between what we are instructed to look at and what we are naturally compelled to look at in a figurative work.”iii What is challenging about this

Also arising from photography and the networks of looking it facilitates, is one of the earliest portraits in the exhibition, Fidel’s #2, painted in 2005. This curious work pre-empts the themes and approaches that Fragar will explore in her portraits over many years. The work draws together several disparate visual elements and associations. Its title is borrowed from the sweater that the artist’s son wears, advertising a café of that name. On the left, the boy is preoccupied by something in front of him but out of frame, while on the right, Fragar is distracted and made impatient by the photograph being taken. Her raised hand, brutally central to the composition, emphatically signals this is not a suitable maternal moment to record. Her hand, bleached white in ‘photographic’ overexposure, is a clear message to the photographer to STOP. The gesture fails on several counts: the photograph is taken; the hand does not obscure anything of importance in the image, we still see mother and child and their setting; and finally, Fragar’s own resistance to the original representation is overcome in her choosing to paint and therefore emphasise the very image she tried to stop.

Tellingly, the artist resists the description of her works as layered, describing them instead as “many images knitted together”iv

This seems a clear indication of Fragar’s commitment to the synchronicity of her painting, not despite but because of the resistance to this the medium rests in. It may be that the artist refuses the idea of layering because it too easily suggests the passage of time and episodes in a life following a chronology that lends itself to an easy narrative based in a logic of cause and effect to arrive, inevitably, at the particularity of a life. Even so, if we accept that the multiple images we find in Fragar’s canvases are not layered, we still feel the need to acknowledge a hierarchy of images that helps facilitate their narrative unfolding.

are painted across the surface of the work, drawing attention to both the artifice of the canvas and an underlying personal dilemma of some kind. The phrase refers to self-made situations, the consequences of which must now be lived with. But by using “make”, rather than “made”, it implies that the scenario is still in the making and that Fragar has resigned herself to the heavy work of making decisions and living with them. In Fragar’s signature style, she also introduces humour to the second version of the work, where she paints a line drawing of a bull over an image of her dumping the manure on the ground. It is a simple visual gag linking bull and shit but also a deft disruption by the insistently male, brute force of a bull that should seem inconsequential in its unsophisticated and transparent rendering next to the solid verisimilitude of Fragar’s own figure in apparently three-dimensional space, and yet, importantly, is not. In both versions of this painting, Fragar introduces competing elements to her underlying painterly agenda. These almost graffitied incursions draw our attention to the difficulties of communicating complex, emotional narratives in paint. Yet while risking undoing much of her labour in painting, they advance her cause and cut through to a sharper, more telling network of representational modes that emphasises the necessity of risk taking and its consequences in art and life.

Two closely related works, Make Your Bed Now Lie In It, and Inside the Ring: Make Your Own Bed Now Lie In It, both 2009, demand a narrative reading and demonstrate something of this hierarchy. Fragar depicts herself in a suburban backyard, framed by a typical suburban wooden fence that blocks the view beyond the yard. The diminutive Fragar battles a bag of manure as she prepares the bare ground for planting. In this claustrophobic setting full of labour, the words “Make Your Bed Now Lie In It”

While Fragar’s paintings assemble a concatenating array of visual references and iconographic signs of an individual’s life story and its intersection with others, the relative transparency or opacity of her figuration opens the portraits to temporality and therefore to addressing painting’s problem with the duration of narrative. That is, through ascribing different values to visual elements through relative transparencies and degrees of clarity, the paintings reward different types of interrogation, both in terms of distance and duration of looking. Walter Benjamin described early photographic portraits as showing the sitter arriving into

their depiction through the long duration of the exposure, of coming into their own being as they turned into the moment and away from the outside world.v Similarly, Fragar’s multiple images, their symbolism and deliberate moments of incoherence of composition mean the viewer builds their understanding of the subject through reading around the image in space and time. While a variously intriguing or heady amount of information is communicated through this strategy, there is no easy or obvious way to draw these elements together into a coherent narrative, though we sense this should be possible and make narrative threads as we look from detail to detail.

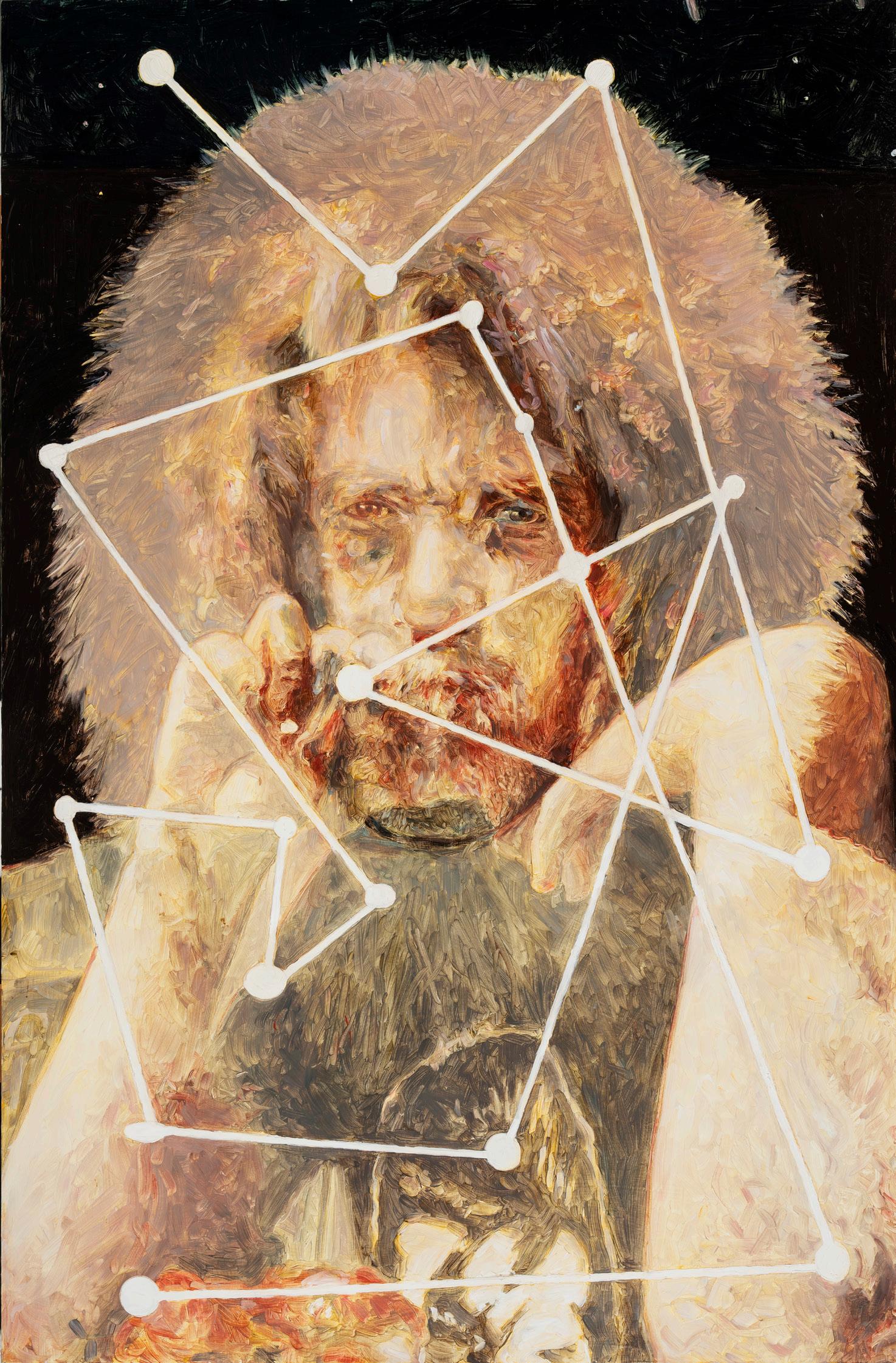

this gritty and monumental work. Its large scale demands that the viewer is constantly in flux in its reading, stepping back to take in the whole but moving in close to the canvas to read details and admire the technical prowess of the painter: from the precisely rendered hairs on Bell’s chest to the creases in his face to the curious subimages that surround him. Bell’s narrative is revealed through this active reading. He tells the story of his family home being demolished by local authorities in southwest Queensland, and in the background to his central image, there are references to that story, showing bent corrugated iron and bed springs. In Fragar’s now familiar knitting together of images, a heavy chain necklace is introduced to the painting as a sign of Bell’s survival and defiance. Bell bought the necklace in 2003 when he won the Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Prize and its inclusion here brings his worlds of trauma and success together.vi

A portrait of Richard Bell, Richard, 2020, makes him viscerally present and dominant in the room, just as he would be in life. Yet when we move closer to the work, as encouraged by its skilful rendering, we see the smaller, fainter imagery present there on the same picture plane but as if swimming in space, as if imagined or recalled. In this way, the portrait presents multiple sides of the artist and activist in

Colour is another key tool in Fragar’s hierarchy of associations in portraiture, often working in surprising ways and once again risking the disruption of her broader painterly effects. This aspect of her work ranges from the reduction and control of colour in a work such as Fidel’s #2, to the amplified cinematic palette of Self-sufficient Self-portrait, 2008. Her monochrome works recall the black and white of documentary photography, a visual trope that supposedly takes us back to bare facts, and in Fragar’s hands, to washed out, exhausted experience. There are numerous examples of opposed and heightened colour that we could refer to here, but we are most struck by Fragar’s more recent and repeated use of an almost fluorescent pink, which despite its high tone appearing within otherwise tenebrous works, is from a distance easily overlooked. You will find this effect in works such as, The Single Bed, 2017, and This is Not a Dress Rehearsal: A Catalogue of Final Options, 2019. When close to the image surface we see just how extreme and discordant this pink is. It is not interested in figurative realism and yet it animates the

work both in shaking up the picture plane and the coherence of its figurative effects but also as a shrill note of what Fragar refers to as the “life blood” of the workvii. The pitch of this pink alludes to an acute recall of experience but in its deliberate out-ofplaceness, also amplifies the chattering noise and incoherence of lived experience. Fragar’s technical and conceptual abilities in paint are undisputed. Throughout her work she uses the potential of the painted image to convey the tragedies, the mundanity and the complexities of human existence. Her portraits as sites for looking at and understanding experience and the intense relationships that arise from that, are endlessly intriguing and demanding. As she knits images together, the progression and impression of narrative is both fragile and affective. In this way her work evokes

complex, multi-faceted stories without setting them in place. Instead, they remain open to our interpretation, to our active engagement and as such, open to us all to recognise and reflect upon our own experience.

Dr Rosemary Hawker Adjunct Associate Professor Queensland College of Art Griffith University & Professor Elisabeth Findlay Director Queensland College of Art Griffith Universityi. Mary Ann Doane, “The Indexical and the Concept off or of? Medium Specificity”, Differences: A Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, 2007, 128-152.

ii. Julie Fragar, “Kissing the Toad: Marlene Dumas and Autobiography”, PhD thesis, Griffith University, 2014, p. 112.

iii. Fragar in conversation with the authors, 10 September 2022.

iv. Kubler, Art Collector https://artcollector.net.au/julie-fragar-new-directions/ (Originally published in Art Collector, issue 71, Jan-Mar, 2015.)

v. Benjamin, Walter. “A Short History of Photography.” In Classic Essays on Photography, edited by Alan Trachtenberg, 199-216. New Haven: Leete’s Island Books, 1980.

vi. Julie Fragar quoted on the Art Gallery of New South Wales Archibald website: https://www.artgallery. nsw.gov.au/prizes/archibald/2020/30218/

vii. Fragar in conversation with the authors, 10 September 2022.

ESSAY THREE TIME AND DEATH IN THE PAINTINGS

OF JULIE FRAGAR

Written by Francis E ParkerApproaching Julie Fragar’s painting practice, I started out wanting to better understand why she layers multiple images over pictorial space, but what I thought would be a spatial question became a temporal one. The layering and splicing of photographic images into what she refers to as composite paintings involves a disruption of the time of painting by the time of photography. Thinking about time, times past and the end of time, I notice a recurrent interest in death in Fragar’s work. She has visualised the multiple possible ways in which it may take her one day in This is Not a Dress Rehearsal: A Catalogue of Final Options, 2019; she has observed the proceedings of murder trials for the series Next Witness, 2019; it is inevitably present in the wings of the operating theatre where she shadowed a surgeon for another series, The Cut, 2020; and, going back to 2010, there was her series devoted to a hunter called Jason, who she painted with his kill. My eye was first caught about fifteen years ago by her re-paintings of works by Gustave Courbet, such as her Master and dog in heavy black coats (get up), 2008, and of her own domestic photographs – replicating the past and photography having, in their respective ways too, a relationship to time and to death in Fragar’s practice that I will consider here.

‘What you are, I once was; what I am, you will be.’ So reads the Latin inscription over the entombed skeleton beneath Masaccio’s 1424 fresco of the Holy Trinity in Santa Maria Novella, Florence, and I wonder if there must be something of the same

frisson one feels in reading this message that tickles painters’ spines when they enter the museum. Seeking to commune with their antecedents, by which I mean taking on the task of re-making works by historical painters, is literally a dialogue with the dead, one that Fragar draws on explicitly in her thesis chapter on Marlene Dumas’s re-interpretations of Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb, 1521i – itself a very similar composition to the above detail from Masaccio’s fresco. In her own re-making of and quoting from historical paintings, Fragar shows not only her deep regard for such figures as Courbet, but also an implicit acknowledgement of the passing of time and of lives.

Of course, as generations of academicians knew, copying from a master – Fragar designates Courbet as such in the title above, so I use the word advisedly – is a way to find answers for the problems that open up in one’s own practice. Literally, ‘What would Courbet do?’ In that respect, she was following a venerable tradition in Western painting with these earlier works. For any painter working in a largely figurative idiom in the twenty-first century, however, the resurrection of figuration – even as, one must acknowledge, it cannot be said that it really did die off with the ascension of abstraction, nor that abstraction has abated either; they coexist, often within the same artist – in addition to more than a century’s grappling with the implications of photography, these are points in the cultural landscape to which one must orient

one’s self as an artist. It is pertinent perhaps that Fragar took an interest in Courbet, who was of the first generation to deal with the dilemma that photographic technologies posed for the painter. She also had an early interest in photorealist painters and the reality effect of photography but ultimately her approach is more to use it as a tool, like preparatory drawings. Indeed, even artists who take historical paintings as a source for their own work largely do so now by looking at photographic reproductions, which Fragar demonstrates pointedly in Looking for D-Rection, 2009.

If working from photographs is as germane to representational practice now as making sketches, and photography is simply useful for its accurate rendering of the world, when the photographic sources are made evident in a painting, something shifts. The nature of photography’s relationship to time is alien to it. It freezes an instant forever, which is part of its romance – if one’s taste is for gothic romance. This fixing of time quickly came to be associated with death, or at least dread in the case of Honoré de Balzac, who imagined that each daguerreotype would peel off a layer of his being. Thinking of death and photography, I cannot help but hear Roland Barthes exclaim, on coming across an 1852 photograph of Jérôme Bonaparte, youngest brother of Napoleon, ‘I am looking at eyes that looked at the Emperor.’ii The anecdote recalls the address to the viewer by the skeleton in Masaccio’s fresco. This unnerving capacity for a photograph to hold time in stasis is what disrupts the temporality of painting, which, even though it might offer a glimpse into the past, reads like a continuous present, a narrative that replays each time the eye falls upon it. This has to do with the gesture of painting, as

Fragar explains, ‘a hand moves across the surface at one moment in time, and we relive those moments in another.’iii

Photography, by contrast, is a mechanical process, instantaneous rather than taking time like living image-makers do. But as Fragar says elsewhere, ‘painting photographs too there’s an inherent sense of bringing something to life, about putting time and the hand in it. When you paint a dead thing, we know that there’s nothing behind the eyes … I’m interested in this idea that there’s nothing behind the surface.’ Historically, paintings were conceived as windows into a pictorial space; however, working from photographs in a way that renders their material qualities apparent shuts off that imaginary space and emphasises that there is nothing behind the surface.iv Fragar’s technique of building up a composition from multiple photographic sources, not suturing them together into a seamless whole but rendering them as translucent layers through which their details compete and overlap, prevents the eye from perceiving imaginary depth.

There is then a spatial aspect to this investigation after all. Fragar’s compositions deflect the eye across their surfaces rather than open up onto imaginary spaces. Her aim is not to represent a pictorial reality but a psychological one, replicating the way thoughts collide, get lost, interrupt each other – even slow down – her paintings can be like the image that replays in the mind, one’s eye passing over it repeatedly to retrieve a detail or relive a pleasure, or a pain. Fragar’s composite paintings convey a complexity of experience that a singular image would struggle to do and they evoke the plasticity of time as it is lived.

i. See Julie Fragar, ‘Likeness of Deadness: The Role of the Undertaker’, in ‘Kissing the Toad: Marlene Dumas and Autobiography’, PhD thesis, Queensland College of Art, 2013, pp. 101-14.

ii. Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard, Vintage, London, 2000 [1980], p. 3.

iii. Fragar, ‘Kissing the Toad: Marlene Dumas and Autobiography’, PhD thesis, Queensland College of Art, 2013, p. 102.

iv. Julie Fragar, video interview, Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2010, https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/art/watch-listen-read/watch/180/.

LIST OF WORKS

This is Not a Dress Rehearsal: A Catalogue of Final Options 2019 Oil on board, 270 x 200 cm

Apex Jumping Castle 1998

Oil on canvas, (36) 10 x 15 cm panels

The Gary Owen (Rozelle) 1999 Oil on canvas, (9) 10 x 15 cm panels

Blaugrau (Chippendale) 2001 Oil on canvas, (9) 10 x 15 cm panels

Flagyl, New Year’s Eve 2000 2000 Oil on canvas, 120 x 180 cm Collection, HOTA Gallery. Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program by Sam Kent 2002© Image courtesy of the artist and Sarah Cottier Gallery

Selina I 2001

Oil on canvas, 60 x 90 cm

Selina II 2001

Oil on canvas, 60 x 90 cm

S [detail] 2004

Oil on canvas, 91 x 60.5 cm

Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art, The University of Western Australia

I’M A LADY 2003 Oil on board, 61 x 45.5 cm

Not in the Mood for Sacrifices 2003 Oil on board, 61 x 45.5 cm

Fidel’s #2 2005

Oil on board, 40 x 60 cm

Berry’s Head 2006

Oil on board, 60 x 40 cm Private Collection

Self-Sufficient, Self-Portrait 2008 Oil on board, 60 x 90 cm

Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art, The University of Western Australia

Original Flat Screen (Get Up) [detail] 2008 Oil on board, 60 x 40 cm

Collection of Todd McMillan & Sarah Mosca

Knocked off Her Feet (get up) [detail] 2008 Oil on board, 60 x 40 cm

Purchased 2009 with funds from the Perpetual Foundation Beryl Graham Family Memorial Gift Fund through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art

Above: Master and dog in heavy black coasts (get up) 2008 Oil on board, 60 x 40 cm

Purchased 2009 with funds from the Perpetual Foundation Beryl Graham Family Memorial Gift Fund through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation Collection: Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art

Next Page: Grandma (Alzheimers) [detail] 2008 Oil on board, 135 x 90 cm

Ready (Penelope) 2008 Oil on board, 60 x 40 cm

Filling in the Blanks 2009 Oil on board, 60 x 40 cm

Collection: Art Gallery of New South Wales - Viktoria Marinov Bequest Fund 2010

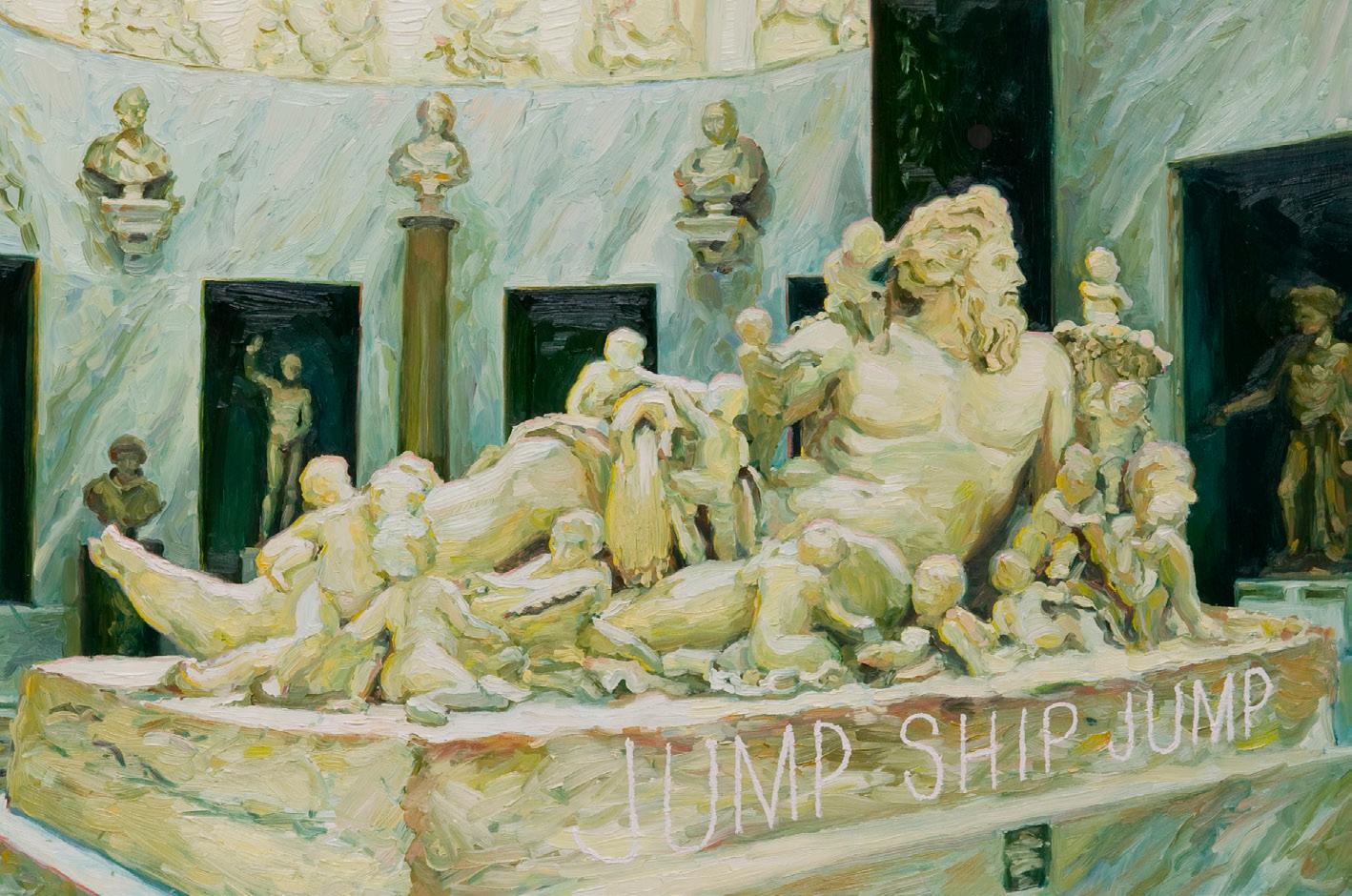

JUMP SHIP JUMP 2009

Oil on board, 40 x 60 cm

Collection: Art Gallery of New South Wales - Viktoria Marinov Bequest Fund 2010

Looking for D-Rection 2009 Oil on board, 40 x 60 cm

Collection: Art Gallery of New South Wales - Viktoria Marinov Bequest Fund 2010

Make Your Bed Now Lie in it 2009 Oil on board, 40 x 60 cm Private Collection

Inside the Ring (Make your bed now lie in it) 2009 Oil on board, 40 x 60 cm Collection of Jonathan McBurnie

Guarded 2009

Oil on board, 60 x 40 cm

Private Collection, Brisbane. Courtesy of Bruce Heiser Projects

Pointing Like an Arrow to the Main Game 2010 Oil on board, 60 x 40 cm Private Collection

Kind of Woman 2010

Oil on board, 90 x 135 cm Private Collection

Undercover Self Portrait 2010 Oil on board, 60 x 40 cm Private Collection

Hung, Drawn, Quartered, Seasoned (self portrait) [detail] 2010 Oil on board, 182 x 122 cm

Moreton Bay Regional Council Art Collection

Polygraph [detail] 2010 Oil on board, 180 x 120 cm

Meet me at Arms Length 2010 Oil on board, 59.9 x 40 cm

Collection of The University of Queensland. Gift of Professor Alan Rix through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program, 2016.

Self-Portrait at the End 2010 Oil on board, 60 x 40 cm Private Collection

Making it work-working it out 2010

Oil on board, 60 x 40 cm

Private Collection, Brisbane. Courtesy of Bruce Heiser Projects

Slow Lane 2010

Oil on board, 60 x 40 cm Private Collection

Draw Breath 2012

Oil on board, 60 x 40 cm

Collection of Dr Terry Wu, Melbourne

Marathon Boxing 2012

Oil on board, 60 x 40 cm Collection of Dr Terry Wu, Melbourne

Ghost God 2012

Oil on board, 60 x 40 cm Collection of Dr Terry Wu, Melbourne

Poking the Ghost Skin 2012 Oil on board, 60 x 40 cm Collection of Dr Terry Wu, Melbourne

Single-minded Gesture 2012 Oil on board, 60 x 40 cm

Stroke 2013

Oil on board, 60 x 50 cm

Mother Consoles Herself with Blah Blah 2013 Oil on board, 90 x 70 cm Private Collection

Marathon Boxing and Dog Fights 2013 Oil on board, 60 x 50 cm

Not Your Fault 2013

Oil on board, 50 x 60 cm

Collection of Selina McGrath

Gnash 2013

Oil on board, 40 x 60 cm

God and the Universe or Whatever (Oliver) 2013 Oil on board, 90 x 60 cm

THIS HAS NOT MADE ME AS HAPPY AS ONE MIGHT HAVE THOUGHT 2013 Oil on board, 135 x 190 cm

A Man Loved a Woman 2013 Oil on board, 135 x 90 cm Private Collection

Second Consideration After The Fact 2014 Oil on board, 150.5 x 122.5 cm Monash University Collection Purchased by the Faculty of Science 2015 Courtesy of Monash University Museum of Art

Cannibal Tom 2014

Oil on board, 90 x 70 cm Private Collection

Off Sure Feet 2014

Oil on board, 135 x 100 cm

Collection of Dr Terry Wu, Melbourne

Penned like chickens eaten like chickens (Fiji) [detail] 2014 Oil on board, 92.3 x 72.3 cm Rockhampton Museum of Art Collection. Purchased 2015

I Don’t Want to do This Anymore 2015 Oil on board, 90 x 70 cm

Goose Chase: All of Us Together Here and Nowhere 2015 Oil on board, 160 x 122 cm

Gift of the Art Gallery of South Australia Contemporary Collectors 2018, Art Gallery of South Australia

Self-Portrait with Capote 2016 Oil on board, 60 x 50 cm

Antonio Departs Flores on the Whaling Tide 2016 Oil on board, 120 x 160 cm

On loan from the Devonport Regional Gallery. Tidal: City of Devonport Acquisitive Art Award Winner 2016, DCC Permanent Collection 2017.001

You (Susan Skelton) 2016

Oil on paper, 10 x 5.3 cm

Collection of Karen Black

Susan 2016

Oil on paper, 10 x 5.3 cm Private Collection

The Party (Susan Fragar) 2016 Oil on linen, 14 x 11 cm

The Whaling 2016 Oil on board, 100 x 135 cm

HSP Response (Susan Frances Skelton) 2016 Oil on paper, 17.5 x 8 cm Private Collection

Married (Susan and Timothy Fragar) 2016 Oil on linen, 17.5 x 13 cm Private Collection

Portrait of Susan Frances Fragar 2016 Oil on paper, 11.5 x 10 cm Private Collection

Susan and Timothy 2016 Oil on linen, 15.5 x 4.5 cm Collection of Jonathan McBurnie

Your Rules Are Not For Me 2017

Oil on paper, 21 x 14.5 cm Collection of Jasmine and Robert Dindas

The Elephant in the Room 2017 Oil on paper, 14.5 x 19.5 cm

Too Much and Not Enough Water Under the Bridge 2017 Oil on paper, 12 x 18 cm Collection of James Arnott

Man Tortures Woman in Cheap Motel 2017 Oil on paper, 10 x 7.5 cm

The Single Bed 2017

Oil on board, 135 x 100 cm Griffith University Art Collection. Purchased 2017

Intergenerational Fraga/Fragar 2018 Oil on board, 90 x 70 cm Private Collection

Appearing Before the Hawks, the Hounds and Those who Tell the Stories 2018 Oil on board, 140 x 210 cm

Exhibit 30: Post-Mortem Injury (Incise Wound) [detail] 2018 Oil on board, 105 x 70 cm

Richard [detail] 2020

Oil on board, 202.5 x 135.5 cm Museum of Brisbane Collection

There Goes the Floor: Self-Portrait [detail] 2020 Oil on board, 60 x 50 cm

Rain on Your own Parade 2021 Oil on board, 90 x 70 cm

Drown in Your own Ambition 2021 Oil on board, 60 x 50 cm Private collection of Sally Breen

To Spiral 2021

Oil on board, 15 x 10 cm

Beside Myself 2021

Oil on board, 15 x 10 cm

Collection of Susan Best