Publisher

Perc Tucker Regional Gallery

Townsville City Council

PO Box 1268

Townsville City, Queensland, 4810

galleries@townsville.qld.gov.au

© Galleries, Townsville City Council, and respective artists and authors, 2023

ISBN: 978-0-949461-59-9

Published on the occasion of Len Cook: Fire and Rain

Artists

Len Cook

Publication and Design Development

Townsville City Council

Contributing Authors

Ross Searle

Owen Rye

Artwork documentation

Michael Marzik

Jamie Oliver

Photographer

Michael Marzik

Jamie Oliver

Editor

Evie Franzidis

Perc Tucker Regional Gallery

Cnr Denham and Flinders St

Townsville QLD 4810

Tue – Fri: 10am – 5pm

Sat – Sun: 10am – 1pm

07 4727 9011

galleries@townsville.qld.gov.au

whatson.townsville.qld.gov.au

Townsville City Galleries

TownsvilleCityGalleries

Galleries full team listing

Jane Scott Galleries Director

Jo Lankester Senior Exhibitions and Collections Officer

Sascha Millard Collection Management Officer

Veerle Janssens Collection Registration Officer

Leo Valero Exhibitions Officer

Michael Favot Exhibitions Assistant

Chloe Lindo Curatorial Assistant

Rachel Cunningham Senior Education and Programs Officer

Jonathan Brown Education and Programs Officer

Ashleigh Peters Education and Programs Officer

Tanya Tanner Senior Public Art Officer

Caitlin Dobson Public Art Officer

Katya Venter Gallery Assistant

Zoe Seitis Gallery Assistant

Maddie Macallister Gallery Assistant

Rhiannon Mitchard Gallery Assistant

Anja Bremermann Gallery Assistant

Deanna Nash Team Leader Business Support

Sue Drummond Business Support Officer

Christine Teunon Business Support Officer

Abbigail Thomas Business Support Officer

Emma Hanson Business Support Officer

Townsville City Council acknowledges the Wulgurukaba of Gurambilbarra and Yunbenun, Bindal, Gugu Badhun and Nywaigi as the Traditional Owners of this land. We pay our respects to their cultures, their ancestors, and their Elders – past and present –and all future generations.

Len Cook has excelled in one of the most difficult careers an artist can undertake – that of a creative studio ceramicist. I can attest to the many challenges facing the prospective potter, having trained in ceramics at art school, where we dodged lumps of clay flying off the spinning potter’s wheels, the intricacies of glaze recipes and firing techniques, and the character-building (and muscle-building) labour of wedging clay. Even more difficult is the effort and intelligence required to build and develop a self-sustaining studio practice. In his adopted hamlet of Paluma, Len took all this in his stride, with not even a handful of books to guide his first efforts. Through trial and error, he has developed his craft and unique vision, in the meantime reaching out to find those few ceramicists to learn from, and to form a close-knit if geographically scattered community.

As Ross Searle points out in his excellent essay, Len embraces the quite variable results obtained from wood firing. Of the various techniques for vitrifying and glazing ceramics, it is the hardest to master, and the one most prone to misfortune – yet at the same time able to enrich the beauty of the finished work. We find in Len’s art practice not only the adoption and adaptation of Japanese technology and work methods but also a deep understanding of that element of aesthetics known as wabi-sabi, meaning the embrace of imperfection, of chance effects that can never be exactly replicated.

Japan has a long tradition of recognising its artists and master artisans as living treasures. We may be sure that Len, crafting his work in a corner of a somewhat larger island nation, can be counted among their peers.

This exhibition could not have been possible without the generous support from institutions, patrons, and private collectors. Firstly, our thanks to Len Cook for his extraordinary art, Ross Searle for his vision and dedication in curating this wonderful exhibition, and Owen Rye for his unwavering support of both Len and wood firing.

Thanks to our institutional lenders HOTA, Rockhampton Museum of Art, and the North Queensland Potters Association and to our private lenders Rosie O’hearn, Dana McCown, Jane Hawkins, Isabelle Boyle, Wendy Bainbridge, Bill Cook, Margot Douglas, Douglas and Leanne Williams, Marissa Pietrobion, Phyllis Leong Rainford and the late David Rainford for allowing us to share their treasured personal collections. There are also those lenders who wish to remain anonymous. We thank you for your loans and your belief in this project. Lastly, thanks to the staff of the Perc Tucker Regional Gallery for their thoughtful and professional support of this important exhibition.

Jane Scott Galleries Director Townsville City

Council

Townsville is a flourishing centre for the ceramic arts, with an active community of locally based potters who participate in regular exhibitions and programs with visiting teachers. Its history follows a common thread across Australia through the consciousness raising and activism of the national craft movement in the 1970s, the expansion of tertiary training to include dedicated specialist courses in ceramics, and the coming together of like-minded people to form potters’ societies. Townsville’s own North Queensland Potters Association was established in 1972 and it parallels the establishment of the Queensland Potters Association in Brisbane four years earlier. In Australia the seeds of the studio ceramics revival took place during the post–World War Two period. In the mid-to-late 1950s, the stoneware pottery movement was in its formative stage with Harold Hughan in Melbourne, and Ivan McMeekin and Peter Rushforth in New South Wales. Hughan’s first efforts in stoneware were in the Anglo–Japanese tradition, added by C. F. Binns’s The Potter’s Craft (1910), which taught him to throw pots on a wheel he devised from the crankshaft of a motorcar engine. He soon built his own kiln and made stoneware in a workshop behind his Melbourne home.1 The influence of the English potter Bernard Leach and his ground-breaking publication A Potter’s Book (1940) contributed to a worldwide interest in Japanese ceramics. This tradition was introduced indirectly into Australia in the mid-1950s by McMeekin and was reinforced by Australian potters who travelled to Japan in the 1960s and 70s.

Leach’s aesthetic also reached Queensland and influenced studio potter and teacher Harry Memmott (1921–1991), who visited Japan in the late 1960s before moving to the Dandenong Ranges, Victoria, to take up a position at the Prahran Technical College. Perhaps Queensland’s bestknown potters were US-born father and son, Carl and Philip McConnell. Carl (1926–2003) was the most important potter in the post-war generation in Queensland, introducing stoneware and porcelain firing to the state, particularly through woodfiring, which already had a long history in Asia. He brought kiln designs from the US influenced by this style of firing. Phillip (b. 1947), Carl’s eldest son, followed in his father’s footsteps and established a

career of equal significance. Both artists had been influenced by the Anglo–Japanese tradition, initially through Leach but more directly when Phillip went on to study at Bizen, the ancient Japanese pottery centre, in 1973–4. As Australia’s trade relationships with Japan developed from the 1960s onwards, so the influence of Japanese ceramics on Australian artists became more direct.2

Len Cook became interested in pottery after he moved to Townsville from Victoria in 1977. A chance encounter with a young lady and her mother introduced him to Memmott’s The Australian Pottery Book (1970) which was to be transformative in terms of introducing him to the clay medium, its preparation, throwing, aspects of hand building, use of moulds, decoration, the application of textures to surfaces, glazing and firing. It became an essential handbook for all studio potters. As Len recalls, with the Memmott book as his guide, he built his first kiln. With ‘a plan of a basic Raku kiln made from household bricks left over from a new house being built at Kelso collected by mother and daughter, I set about building this small Raku kiln in their backyard. I also built a treadle kick wheel to make pots.’ 3 Completely self-taught, the trio ‘had some success with the kiln and the wheel.’ 4 With the aid of a home-made blower from an old VW motor and burner using diesel fuel, he was able to get the kiln to stoneware temperatures, but it also melted all the house bricks.

This was followed in the same year with Len attending an intensive 10-day workshop convened by the North Queensland Potters Association. Led by Carl McConnell, the workshop introduced Len to traditional methods of firing, and it ignited a lifelong passion for woodfired kilns and pots that are glazed by natural ash deposits over extended firing in ‘traditional’ Japanese anagama (cave) kilns. It was McConnell who ignited Len Cook’s love of East Asian ceramics.

Len Cook (b. 1951) was born in Bacchus Marsh, Victoria. His father was a builder and his mother a home-maker, and he had three brothers and one sister. His parents realised early in his life that he had an artistic streak, and his father purchased an upright piano for Len while he was at primary

school. As Len recalls, ‘the downside to this was while all the other children were doing art class, I was being taught to play the piano’.6 His love of music continues to this day through his instrument of choice, the guitar. As he grew older his interests turned to cars and he restored a vintage 1924 Dodge Brothers Tourer. His father was also quite the craftsman-carpenter, having built a curved staircase in the family home in 1957, the only one of its kind in Bacchus Marsh. ‘This was revolutionary at that time and given a chance, he could have been quite good at some artistic endeavour but was too busy working and bringing up a family.’5 With such a supportive family, it is little wonder that Len settled on pottery initially as a hobby and then as his artistic calling. By 1980 he had set up a studio and sales outlet in the mountain village of Paluma, 85 kms north of Townsville.

His formal studies followed soon after moving to Paluma, and he completed a Certificate III at Townsville College of TAFE before taking up a teaching position at its Pimlico Campus in 1984. His formal studies continued in 1993 through Monash University’s regional Churchill Campus, where he was taught by the eminent traditional wood-firing potter Owen Rye (b. 1944). Other students in this group included the Queensland potters Rick Wood (1949–2007) and Rowley Drysdale (b. 1957), both of whom later pursued full time careers as potters. While he had known Wood from an earlier time, he met Drysdale in the first year of his studies. As a student, Len attended the first wood-firing conference held at Churchill Campus. ‘It was a great way to meet like-minded woodfiring potters and it strengthened my resolve and direction as a potter.’ 7

For Len, ‘Owen’s teaching encouraged me to loosen up my forms. Having him as my supervisor was invaluable’.8 This gave him the confidence to take greater risks in his handling of clay and firing methods. Once he completed his Graduate Diploma in Visual Arts, he never looked back as a fully fledged potter.

Wood-fired kilns can not only produce temperatures of 1400°C, but wood fuel also produces fly ash and volatile salts. This complex interaction of ash, salts, minerals in the clay and the flame itself are what give wood-fired pots their unique characteristics. Wood ash might lightly settle on a piece during the firing or accumulate to the point where the ash drips down the sides of a pot, or the ash might even accumulate around the pot until it is completely submerged. Placement of pieces within the kiln also greatly affects the pottery’s final appearance; pieces closer to the flame may become immersed in embers and ash, while those further from the flame

may only be lightly touched by ash effects and salt. In the hands of Len Cook, who uses hardwood timber collected from western Queensland, local clays including those with a high concentration of Felspar, the results are often unique in terms of the rough textures and concentration of heavy ash deposits. Felspar is the most abundant mineral group in the Earth’s crust and the resulting mineral inclusions often endow Len’s pots with a robust, rugged characteristic.

An anagama kiln is an ancient type of pottery kiln brought to Japan from China via Korea in the 5th century. It is a version of the climbing dragon kiln of south China, whose further development was copied to create the noborigama kiln. This form of kiln generally means a kiln with a partitioned chamber for firing large quantities of ceramics, built on a slope so that the draft from the burning timber draws the flue gas through the kiln, keeping the high temperatures constant throughout the chamber. By the 1970s wood-fired kilns were becoming more common as Australian potters returned from Japan armed with firsthand experience in the techniques of kiln-building. Milton Moon is credited as building the first anagama kiln in Australia.8 Earlier experiments took place in 1954 at the Stuart Pottery where Ivan McMeekin fired the first bourry kiln in Australia. He first encountered this form of wood-fired kiln in England at Michael Cardew’s studio, took the design of Cardew’s temperamental kiln and perfected it in Australia.9

Interested in wood-fire kiln design, Len was surprised to discover that a double bourry-box kiln was being built by a local potter Peter Brown. As a novice, Len was fascinated by the construction and firing of this kiln which led to his own experiments in building kilns. His first hands-on involvement with building an anagama kiln was on a friend’s farm in 1990. The site was problematic due to the location on the hot, dry coastal plain between the Paluma Range and the sea at Coolbie. The results were less than spectacular. The kiln had a relatively short life after the land was sold and was no longer accessible. Undaunted, he abandoned the hot, dry conditions for the more amenable environment of the Paluma Range and built a progression of kilns, including a catenary kiln.

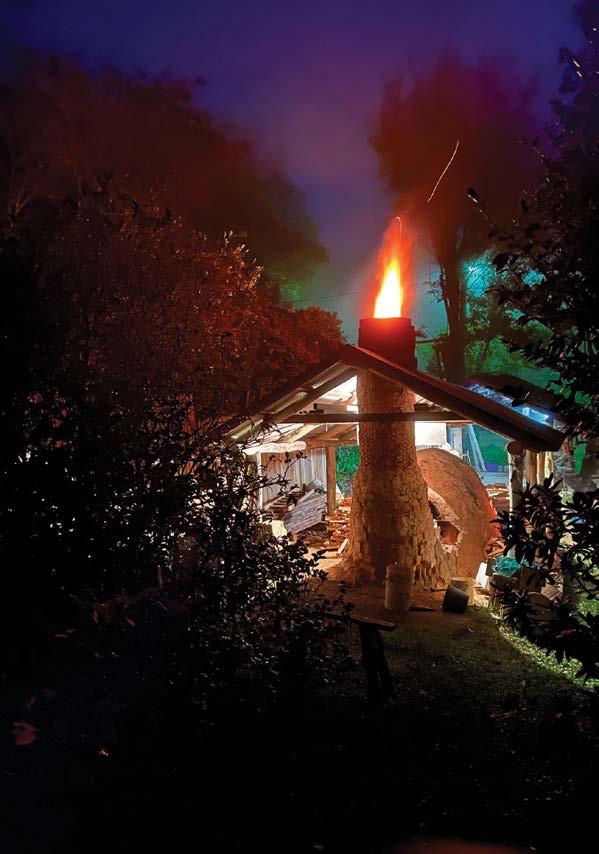

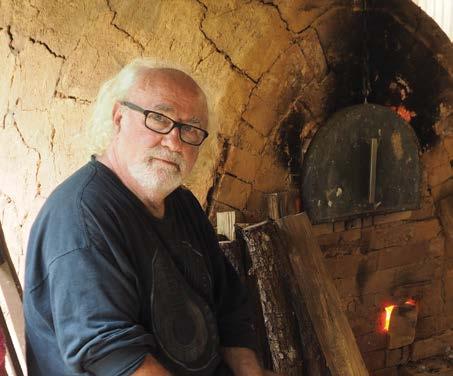

Len’s current anagama kiln is located on the sloping land of his front garden at his Paluma studio. Paluma is not far from the sea and Len’s studio is near the top of the range so there is frequent precipitation from condensation from low clouds. This unique location ensures a constant cloud cover and when fired, his anagama kiln produces a remarkable fiery spectacle in the evening sky.

Wood for the kiln is stored in drier country a few kilometres to the west and trucked in just before each firing. He fires with Australian hardwoods (eucalypts), together with blackwood (acacia melanoxylon), pine, and umbrella tree. The firings last 90 to 96 hours. His shutdown procedure is to allow the side stoke embers to burn away well before the end of the firing and the side stoking ports are clammed up prior to finishing the main stoking. At shutdown, the front firebox is filled with wood, usually pine, with a tiny amount of air entering the kiln via the mousehole, and the damper is closed. The temperature usually climbs during this procedure. After the wood burns away in the front firebox, causing heavy reduction, the kiln cools down in oxidation. The kiln is allowed to cool for about a week before opening.

Fire and Rain includes some of Len’s earliest creative works, including Platter (1978), a stoneware platter with landscape decoration that was acquired in 1978 for the City of Townsville Art Collection. It was overall winner of the North Queensland Potters Association annual award for that year and stands out even today in terms of the skill required to throw, trim, and decorate such a large platter. Its bold ‘landscape’ design was achieved by both pouring glaze and finishing off with a brush. This is an astonishing achievement for a fledgling potter who had only arrived in Townsville a year earlier having never worked with clay. Other early gasfired works include Skirted Teapot (1987), finished in a dark tea dust glaze with a shape reminiscent of the Japanese kettle used for heating water for the tea ceremony. The skirted section envelopes the unglazed body shape. A later work, High Tide (1997), points to Len’s interest in working with locally dug clays. Here he was able to create a local fish-scale glaze rich in colour. For Len, incorporating local clay became increasing important as a means of achieving a ‘local’ effect, much like Japanese potters who worked with what they had available to create shapes and glazes particular to their village or region, so much so that ‘if potters had a short type of clay, their work evolved around cylindrical shapes and if other village’s had plastic clays, they made spherical shaped forms’.10

As Len’s work evolved, his forms became more robust and innovative. Rye’s teaching encouraged him to loosen up his forms, as evidenced in the works created from the mid-1990s onwards. Classical shapes derived from traditional Japanese pottery such as the tea bowl, bottle, vase, and gourd shape became more pronounced and striking. His old friend Rowley Drysdale noted in his judge’s comments that Len’s award-winning entry to the Pioneer Potters Awards 1997 was ‘a wonderfully rugged piece with a highly individual

surface’.11 Len refers to this as a decision ‘to consciously and deliberately omit additions such as lugs and handles’12 as a way of purifying his forms and to emphasise the ‘texture brought about by the interplay of clay with flame … letting the flame paint the piece with a natural pattern’.13 Len has achieved this in addition to maintaining a steady practice as a production potter. While purists flirted with notions of the ‘total’ concept of the Japanese village potter, which included digging out and preparing the clay, throwing, decorating and finally firing the clay, this is not necessarily easy or practical in terms of the energy expenditure for a studio potter. Len has always been aware that he needed to diversify his studio practice to include gas-fired production wares.

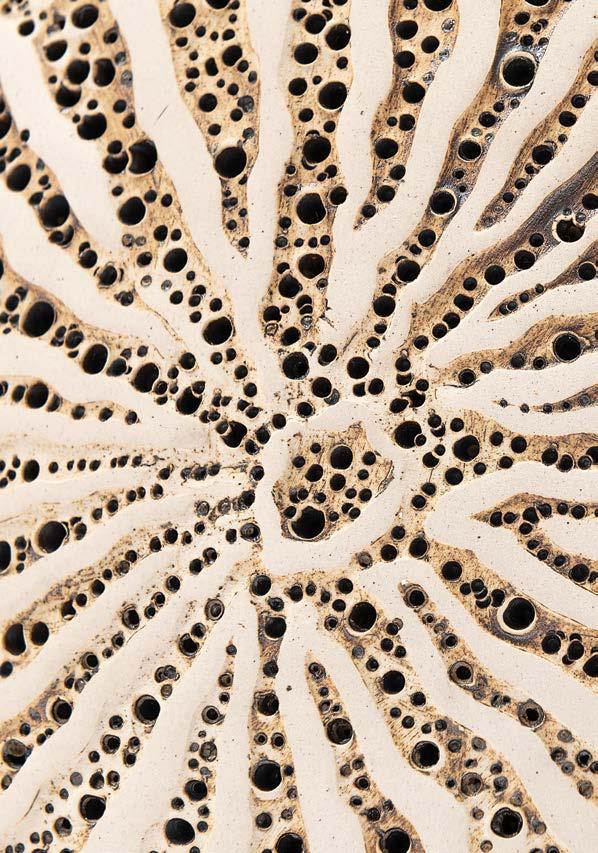

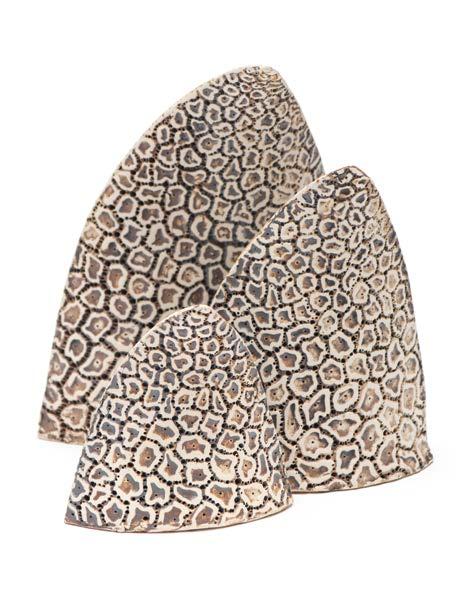

While the more traditional studio ceramics continue to be the mainstay of Len Cook’s outstanding career, there is another strand to his practice in the form of sculptural ceramics inspired by the Barrier Reef. When Len started snorkelling off Magnetic Island in the late 1970s, his senses were ignited by the marine environment. The reef-inspired works now extend his practice beyond traditional Asian ceramics into the sculptural arena where he incises clay surfaces to create free-standing sculptures and wall-mounted disks. These strands of practice are brought to sharp focus in this survey exhibition. The Reef Reflection works sit beside the Asian-inspired pottery, to form a striking counterpoint given their making and firing is so different. Produced in prepared moulds they provide a foil for the more labour-intensive studio wheel thrown or hand-built pieces. There are outstanding examples including Reef Reflections Series #1 (2003) which consists of six elaborate free-standing forms.

Rye observes that ‘the concept of woodfire in ceramics is in some ways an odd one, focussing attention as it does on process rather than product… there is no group of ceramics known as electricfire or gasfire. In part the identification of woodfirers as a distinct group … has resulted from a series of woodfire conferences and gatherings bringing together those who practice the art.’14 This cementing of interest in wood-firing in Australia persists and is dominated by a small but active group dispersed all over the country. Although Len has been a professional potter for over 40 years, it is easy for the North Queensland community to forget how significant he is to this tradition given it is somewhat dispersed in Australia. There is only a small scattering of woodfirers in Queensland. In Len’s hands, the anagama wood-fired tradition finds new possibilities with each firing. Chance and accident are welcome elements in the aesthetics of woodfiring. It is the blemish that holds the key to the success of each firing. With its high percentage

of unpredictable results, wood-firing has revealed to Len the need to be patient and to see each piece for what it is. Over time he has been able to ‘control’ the results of firing by placing bottles and other cylindrical shapes on their sides, allowing the forms to be softened by the intense heat of the kiln, ensuring the ash settles across the form sideways. Reduction in the kiln can also lead to remarkable results of carbon trapping as demonstrated by Bottle, Carbon Trap Glaze (2018).

His love of East Asian ceramics has been the hallmark of his practice and is reflected in the quintessential forms and concerns of his work, brought about by the early career influences of Carl McConnell and his Monash University lecturer Owen Rye. He continues to be inspired by visits to traditional pottery centres in Japan and China and has visited the six ancient kilns in Japan, which are over 1,000 years old. Len’s

recent work demonstrates a further paring of the forms to classical elements that invite pause and contemplation. The forms appear in a harmonious conversation: tea bowls, tall bottles, square vases, gourd shapes, and flower containers, which gain meaning from their association with one another.

Len Cook is a multi-award-winning potter with work represented in public galleries in Australia and overseas. This exhibition profiles the artist’s remarkable practice, highlighting his outstanding achievements and dedication to his craft. It brings together over 100 works spanning 45 years of creative endeavour and includes a substantial body of work created in the past 10 years. Indeed, his reputation in wood-firing continues to grow as he grapples with the complexities of this artform.

1 Terence Lane, ‘Harold Randolp Hughan (1893–1987)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 17, 2007, accessed 12 January 2023, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hughan-harold-randolph-12664.

2 Glenn R. Cooke, ‘Phillip McConnell b. 1947’, Design & Art Australia Online, accessed 18 January 2023, https://www.daao.org.au/bio/ivanmcmeekin/biography/.

3 Len Cook, email to the author, 12 January 2023.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Len Cook, email to the author, 16 January 2023.

8 Owen Rye, ‘Woodfiring in Australia’, 1999, accessed 21 January 2023, https://www.owenrye.com/written-by-owen-rye/woodfiring-inaustralia-1999.

9 Joanna Mendelssohn and Judith Pearce, ‘Ivan McMeekin (1919–1993)’, Design & Art Australia Online, accessed 12 January 2023, https:// www.daao.org.au/bio/ivan-mcmeekin/biography/.

10 Len Cook, email to the author, 7 February 2023.

11 Rowley Drysdale, Judges’ comments collated by Pioneer Potters Mackay Inc, 1997, 2-page document. Copy in Len Cook’s private papers.

12 Cook, email to the author, 7 February 2023.

13 Len Cook, artist statement for the Sixteenth International Gold Coast Ceramic Award, 4 October – 2 November 1997. Copy in Len Cook’s private papers.

14 Owen Rye, ‘Australian Wood-Fire Survey 1996’, July 1996, accessed 20 February 2023, https://www.owenrye.com/written-by-owen-rye/ australian-woodfire-survey-1996.

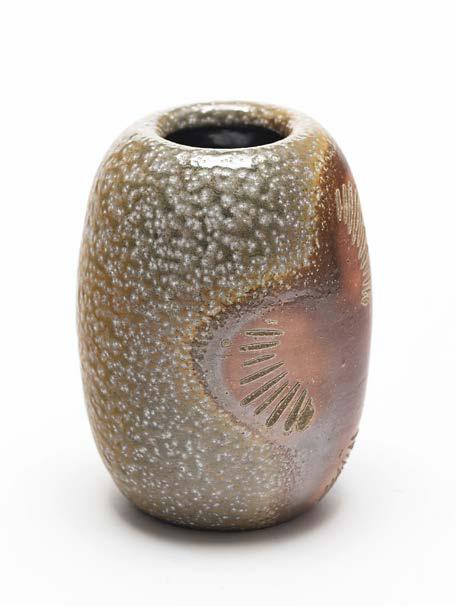

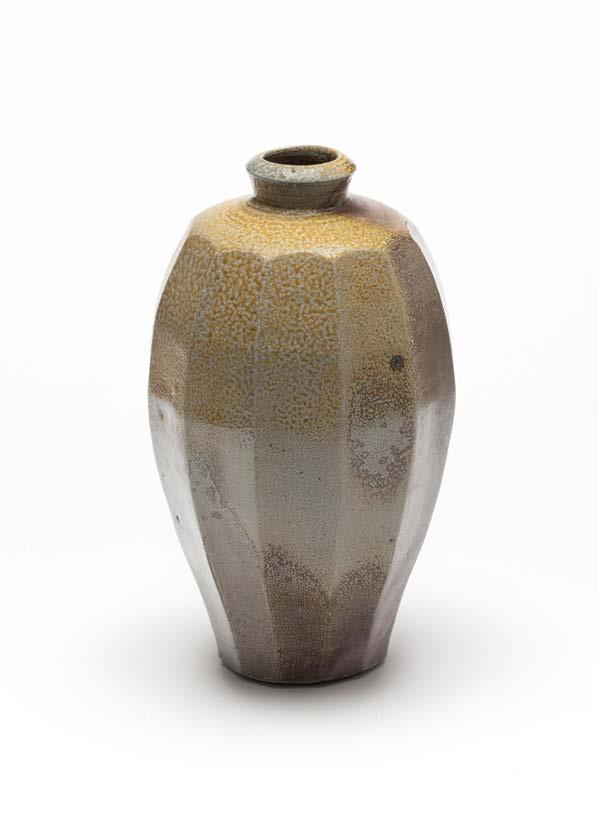

Square Vase, Felspar Inclusions 2002

100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 21 x 15 x 15 cm

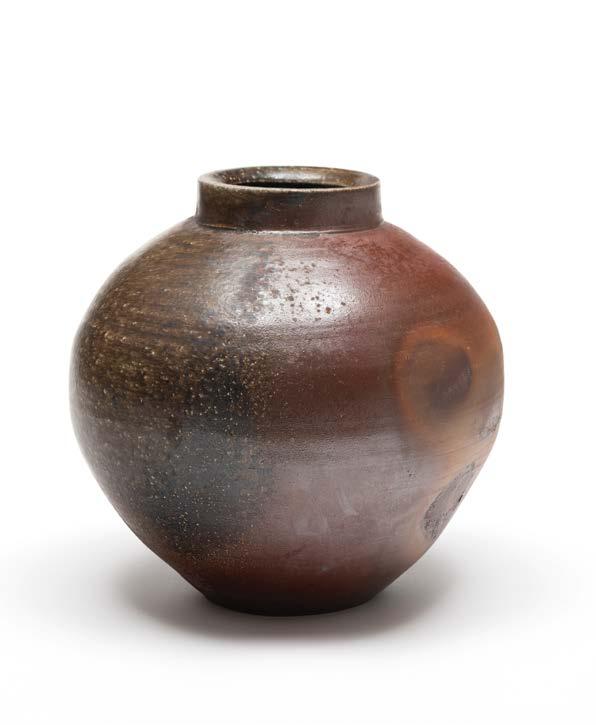

Tea Bowl, Felspar Inclusions 2019

100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 11 x 8.5 x 8.5 cm

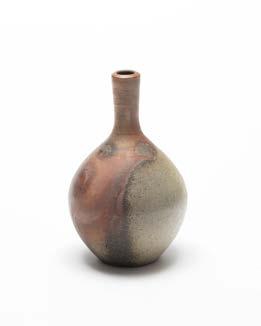

Square Bottle, Shino 2007

100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 28 x 12 x 12 cm

Collection of the artist

Flower Container 2021

100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 10 x 14.5 x 14.5 cm

Wood has been used as a fuel from ancient times. Australian colonial ceramics were fired using wood and in the 1950s Ivan McMeekin and Harold Hughan built wood-fired kilns for their art ceramics.

In the 1970s Japanese wood-fired ceramics inspired some Americans to study in Japan and learn about the anagama type of kiln, a long tunnel built on a slope. Australians Col Levy and Peter Rushforth also visited Japan and brought back kiln designs. Other Australians who had not visited Japan were inspired by the Japanese wood-fire aesthetic seen in books. They built appropriate kilns – each one unique. But as Peter Thompson said once, they brought the technology but forgot the instruction book. So we made it up as we went along – and became known internationally for our distinctive styles of woodfiring.

What is this aesthetic? If you make something –say a vase – from clay, and, using wood fuel, heat it up to 1200℃ or more, then keep it above that temperature for a few days, ash from the burning wood will land on the pot and begin to melt and form a kind of glaze. If the layer is thick enough, it will run like lava. On cooler parts of the pot, the melted ash will look greyish and cratered, a little like the moon’s surface. A bit hotter it will appear like a variegated, matte paint. And where hottest it will look like a glassy lava. That aesthetic is what has become widely known among the ceramic arts in the past 30 to 40 years as wood-firing.

Gallery owners were not interested in the early wood-firing of the 1980s. The aesthetics were too different, too difficult to understand, unlike classical or Modernist forms with fashionable colours that anyone could read. But wood-fired ceramics gradually moved into the mainstream, helped along by articles published in important magazines such as Ceramics Art and Perception; Janet Mansfield, owner and editor, was herself a maker of distinctive woodfired ceramics. In the USA, Gerry Williams, editor of Studio Potter magazine was also a promoter, publishing serious articles.

The first Australian wood-firing conference, held in Gippsland in 1986 attracted 100 wood-firers; it established wood-firing here as a genre. There were few anagamas in Australia; but over time the term ‘wood fire’ became synonymous with anagama kilns, with their ash deposited surfaces. Ceramics from other wood-fired kilns continued though. These kilns were an economic way of firing, producing refined glazes. Gwyn Hanssen Pigott was one of the better-known ceramicists working this way.

Movements in art progress through publicity and selected artists are feted. But wood-firing progressed differently. Events focused on woodfiring became regular and these attracted new people. A few galleries promoted the medium. More importantly, the big kilns, fired over several days, required a team to fire them. Knowledge was spread around informally because individuals helped fire several kilns. For example, with my kiln, some came to help and then built their own kilns –and that was typical.

Various Queenslanders were centrally involved in the wood-firing movement. Anagama kilns were built by Arthur and Carol Rosser, Rowley Drysdale, and Peter Thompson, among others. This brings us to Len Cook. In the 1980s and 90s there were only two places in Australia to study anagama firing – at Lismore with Tony Nankervis or in Gippsland, Victoria at my external postgraduate course. Len studied with me, and subsequently build an anagama kiln, and has been working with these kilns since then.

The key to worthwhile anagama ceramics is to match a random and often unpredictable spread of ash to the surface of a sympathetic form, in a process where accidents and irregularities are standard. This has often meant accepting imperfection as central to the aesthetic. But Len has managed something most others cannot – making precise, controlled (should I say, classic) forms, and marrying them to perfectly appropriate ash deposits. How he does it I do not know; but in this style, he is the Australian master.

Purchased from Len’s exhibition in the North Queensland Potters Association Gallery. North Queensland Potters Association Collection

High Tide 1997

20-hour firing reduction kiln using pine and black wattle. Catenary arch kiln Paluma, 8 x 26.5 cm Purchased with the assistance of the VACB of the Australia Council, 1997. City of Townsville Art Collection. Accession No: 1997.0021.000

Purchased from the Artist, 2001. City of Townsville Art Collection. Accession No: 2001.0036.000

100-hour

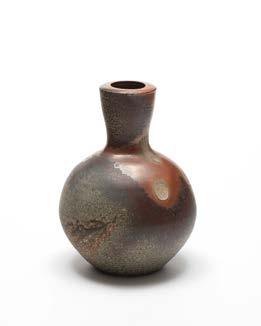

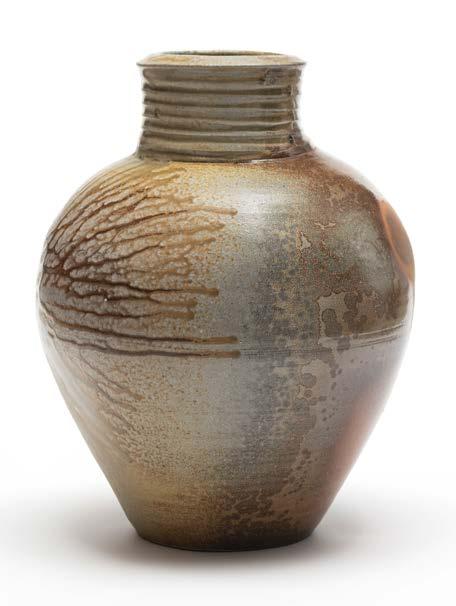

Vase 2002

100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 25 x 17 x 17 cm

Collection of the artist

2002

Reef Reflections Series #1 2003 ceramic, various dimensions Collection, HOTA Gallery. Acquired from the 22nd Gold Coast International Ceramic Award 2003 © the artist

Shino Tea Bowl, Carbon Trap Glaze 2011

100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 9.5 x 8 x 8 cm

Collection of the artist

100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 11 x 8.5 x 8.5 cm

Collection of the artist

Tea Bowl, Carbon Trap Glaze 2019

100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 8 x 11 x 11 cm

Collection of the artist

100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 7 x 21 x 21 cm

Collection of the artist

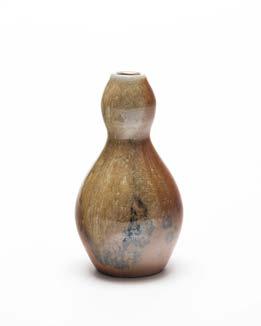

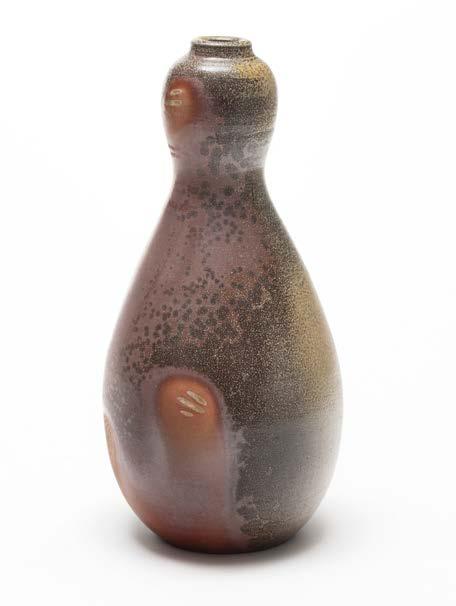

Gourd Shape Vase 2015

100-hour

Collection of the artist

Shape Vase 2015

Flower Container 2015

locally dug clay, anagama wood-fired, glazed,15.3 x 20.5 x 11.5 cm

Purchased from the 2016 Biennial North Queensland Ceramic Awards, 2016. City of Townsville Art Collection. Accession No: 2016.0011.000

Anagama Vessel – Flower Container 2016

100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 24 x 60 cm diam

Purchased from Perc Tucker Regional Gallery, donated by Russ Fraser. North Queensland Potters Association Collection

100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 23.5 x 8.5 x 8.5 cm

Purchased from Perc Tucker Regional Gallery, donated by Russ Fraser. North Queensland Potters Association Collection

100-hour

100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 12 x 13.5 x 13.5 cm

Collection of the artist

Purchased from the 2018 Biennial North Queensland Ceramic Awards, 2018. North Queensland Potters Association Collection

Flask Vase 2021

100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 14.5 x 10 x 15 cm

Collection of the artist

Flask Vase 2021

100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 14.5 x 9 x 14cm

Collection of the artist

Anagama kiln

Anagama is a Japanese word. Ana means cave and gama means kiln.

A tunnel-shaped kiln, usually of brick construction. Preferably built on an incline. Anagamas have no dividing walls, so ware is subjected to flame and wood ash. Usually fired for at least two to three days but can also be longer firings.

Ash

Carbon trap

Chimney

Cones

Damper

Felspar inclusion

Flame thrower

Grate

After the wood is burnt, the ash is drafted through the kiln and a small amount is deposited onto the leading surfaces of the ware.

This is an intriguing glaze which is highly variable. During a cooler part of the firing, carbon enters the surface of the glaze and as the temperature increases, some of the carbon is trapped, which can yield an interesting result.

Located at the back of the anagama, this is an important part of the kiln. The chimney creates a draft to allow air into the front firebox.

Pyrometric cones are placed within the kiln and can be seen throughout the firing. Cones are made of ceramic material which deforms during the firing. These give the potter an indication of the temperature in the kiln.

A series of mechanical shutters which can adjust the amount of air into the kiln.

Clay can also have a certain amount of Felspar included into clay. The results can be varied.

This technique involves completely filling the main firebox door with wood. As the wood is suspended over the firebox and embers it has the effect of a rapid temperature increase.

A series of brick grates built into the main firebox, which allows the embers to be burnt off if the embers get too high.

Natural Ash Decoration

Oxidation

Primary Air

Pyrometer

Reduction

Refractory

Shino glaze

Side stoking

Tumble stack

Wadding

Wicket

Natural ash is deposited onto the surfaces of the pottery. As the temperature increases the ash starts to run like honey, giving the pots a distinctive decoration.

An oxidation atmosphere is where the flame has more oxygen than the carbon in the kiln.

Primary air is introduced into the main firebox to allow complete combustion.

A digital readout device which informs the potter the temperature at that stage of the firing. Very handy for monitoring the temperature in the kiln.

A reduction atmosphere is where the kiln atmosphere has more carbon in the flame. Wood-burning kilns have a cycle of atmospheres.

Refractory clay is used when wadding pots in the kiln. Refractory clay has a very high melting temperature, which is ideal for wadding pottery.

There are many different styles of Shino glaze, ranging from dry white, to pinks, to fire red colours and textures.

Side stoking is a technique of putting kindling-sized pieces of wood into the side stoking ports which are along the sides of the anagama. Side stoking increases the temperature in the kiln at the back of the kiln.

Tumble stacking is used by placing pots directly onto one another with wadding separating each other. No shelves are used.

Usually, a refractory clay is used to separate the ware for either other pots or setting on kiln shelves. Scallop shells can also be used as a form of wadding. The shells leave decorative marks onto the surface of the pots.

This is a technique of of temporarily bricking up the front of the main firebox. After the kiln has cooled sufficiently, the wicket is taken down for unloading.

Platter 1978, stoneware, thrown, poured glaze decoration, brushed decoration. Diesel fired, 5 x 38 cm diam

Skirted Teapot 1987, gas fired, tea dust glaze, 19 x 16 x 16 cm diam

Blossom Jar, Island Deco 1990, gas fired, 24 x 30 x 30 cm

Jar, Woodfired 1993, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 24 x 29 x 97 cm diam

Flower Container 1993, 20-hour firing reduction kiln using pine and black wattle. Catenary arch kiln Paluma, 29.5 x 20 x 20 cm

Flower Container 1993, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle

Vase 1993, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle

Blossom Jar 1996,100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 21 x 23 x 23 cm

Vase 1996, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle

High Tide 1997, 20-hour firing reduction kiln using pine and black wattle. Catenary arch kiln Paluma, 8 x 26.5 cm

Anagama Fired Bottle 1997, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle. Applied local ash glaze, 27.5 x 90 cm

Spherical Pot c. 2000, stoneware, wheel thrown and woodfired with natural ash glaze, 20 x 30 x 30 cm

Set of Bottles 2000, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle. Applied local ash glaze, a. 25 x 9.5 cm, b. 22 x 9, c. 21 x 9 cm

Vase 2001,100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle. Byfield anagama, 21 x 19 x 19 cm

Muroroa Mutations Series II 2001, stoneware slab built, shellac resist decoration with texture inlay, a. 27.4 x 45 x 12.3 cm, b. 21.2 x 28.9 x 7.5 cm variable; c. 17.7 x 23.6 x 8.4 cm

Lidded Jar 2002, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 12 x 12 cm diam

Square Bottle, Shino 2002,100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 28 x 12 x 12 cm

Blossom Jar 2002,100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 24 x 32 x 32 cm

Square Vase, Felspar Inclusions 2002, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 21 x 15 x 15 cm

Vase 2002, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 25 x 17 x 17 cm

Bottle 2002, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle. Byfield anagama, 22 x 14 x 14 cm

Lidded Jar 2002, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 16 x 16 x 16 cm

Bowl, Crackle Glaze 2002, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 11 x 24 x 24 cm

Vase 2002, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle. Catenary arch kiln Paluma, 11 x 20 x 20 cm

Reef Reflections Series #1 2003, ceramic, various dimensions

Flower Container 2004, anagama fired. Local clay, dimensions

Triplophyllites 2008, Stoneware, 41 x 33 x 28 cm (set)

Square Bottle, Carbon Trap Glaze 2010, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 28 x 13 x 13 cm

Gourd Shape Vase 2010, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 38 x 14.5 x 14.5 cm

Bowl 2010, local clay. Anagama fired, 9 x 30 cm diam

Muroroa Mutations Series II 2010, white stoneware, Gas fired, various dimensions

Blossom Jar 2010, anagama fired. Local clay, dimensions

Set of Three Bottles 2010, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle. Shino glaze, various dimensions

Shino Tea Bowl, Carbon Trap Glaze 2011, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 9.5 x 8 x 8 cm

Vase Shino Glaze 2011, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 31.5 x 12 x 12 cm

Tall Vase 2011, Local clay. Anagama fired, 34 x 16 cm diam

Floor Vase 2011, Local clay. Anagama fired, 37 x 18 cm diam

Island Decoration Vase 2012, white stoneware, dimensions

Set of 3 Square Vases 2013, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, a. 24 x 10 b. 20 x 11 c. 17 x 10 cm

Shino Tea Bowl 2015, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 7.5 x 10 x 10 cm

Shino Tea Bowl 2015, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 10 x 7 x 7 cm

Shino Tea Bowl 2015, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 12 x 8 x 8 cm

Shino Tea Bowl 2015, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 11.5 x 8.5 x 8.5 cm

Shino Tea Bowl 2015, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 9.5 x 8 x 8 cm

Gourd Shape Vase 2015, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 16 x 8 x 8 cm

Gourd Shape Vase 2015, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 18 x 7.5 x 7.5 cm

Gourd Shape Vase 2015, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 15.5 x 8 x 8 cm

Square Plate Set of Three 2015, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 3 x 19 x 19 cm each

Vase, Shino Glaze 2015, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 29 x 11 x 11 cm

Bottle, Shino Glaze 2015, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 32.5 x 17 x 17 cm

Bottle, Shino Glaze 2015, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 30 x 16 x 16 cm

Bottle, Shino Glaze 2015, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 31.5 x 19 x 19 cm

Vase With Handles, Shino Glaze 2015, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 39 x 13 x 13 cm

Flower Container 2015, locally dug clay, anagama wood-fired, glazed, 15.3 x 20.5 x 11.5 cm

Anagama Vessel – Flower Container 2016, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 24 x 60 cm diam

Anagama Vessel 2016, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 23.5 x 8.5 x 8.5 cm

Gourd Shape Vase 2017, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 19.5 x 11 x 11 cm

Teacup 2018, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 8 x 7 x 7 cm

Gourd Shape Vase 2018, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 22.5 x 10.5 x 10.5 cm

Lidded Jar 2018,100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 10 x 12 x 12 cm

Lidded Jar 2018,100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 12 x 13.5 x 13.5 cm

Vase 2018, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 33 x 14 x 14 cm

Vase 2018, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 36 x 15 x 15 cm

Reef Reflections x 3 2018, porcelain. Gas fired, 55 x 25 x 13 cm each

Bottle, Carbon Trap Glaze 2018, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 22 x 11.5 x 11.5 cm

Shino Tea Bowl, Carbon Trap Glaze 2019, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 8 x 11 x 11 cm

Shino Tea Bowl, Felspar Inclusions 2019, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 11 x 8.5 x 8.5 cm

Flower Container, Slab Built 2020, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 21.5 x 10 x 10 cm

Shino Tea Bowl 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 7 x 21 x 21 cm

Flower Container 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 10 x 14.5 x 14.5 cm

Flask Vase 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 14.5 x 10 x 15 cm

Flask Vase 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 14.5 x 9 x 14 cm

Square Vase, Slab Built 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 23.5 x 11.5 x 11.5 cm

Square Vase, Slab Built 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 25.5 x 12.5 x 12.5 cm

Square Vase, Slab Built Celadon Glaze 2021, 100hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 21 x 13.5 x 13.5 cm

Square Vase, Slab Built Teadust Glaze 2021, 100hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 20.5 x 13 x 13 cm

Square Vase, Slab Built 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 21 x 16 x 8 cm

Gourd Shape Bottle 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 31.5 x 15 x 15 cm

Bottle, Carbon Trap Glaze 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 28 x 12 x 12 cm

Bottle, Shino Glaze 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 28 x 13 x 13 cm

Faceted Vase 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 38 x 19 x 19 cm

Faceted Vase 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 40 x 18 x 18 cm

Faceted Vase 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 39 x 22 x 22 cm

Tall Bottle 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 45 x 17 x 17 cm

Floor Vase 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 37 x 21 x 21 cm

Blossom Jar 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 39 x 30 x 30 cm

Blossom Jar 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 32 x 35 x 35 cm

Blossom Jar 2021, 100-hour wood fire, reduction kiln using pine and black wattle, 29 x 28 x 28 cm

Wall Plaque (round) 2022, porcelain. Gas fired, 33 x 8 cm diam

Wall Plaque (round) 2022, porcelain. Gas fired, 33 x 8 cm diam

Wall Plaque (round) 2022, porcelain. Gas fired, 33 x 8 cm diam

Wall Plaque (round) 2022, porcelain. Gas fired, 33 x 8 cm diam

Wall Plaques x 3 2022, porcelain. Gas fired. Unstained, no ochre, 8 x 13 x 58 cm each

Wall Plaques x 3 2022, porcelain. Gas fired, 8 x 13 x 58 cm each

Muroroa Mutations Series II 2022, porcelain. Gas fired, a. 28 x 16.5 x 12 cm, b. 22 x 34 x 12 cm, c. 25 x 44 x 160 cm

Double Wall Bowl 2022, local clay. Anagama fired, 5 x 17 cm diam

Leaning Forms x 3 2022, porcelain. Gas fired, a. 26 x 21 x 10 cm, b. 21 x 16 x 8 cm, c. 14 x 12 x 6 cm

Leaning Forms x 3 2022, porcelain. Gas fired, a. 26 x 21 x 10 cm, b. 21 x 16 x 8 cm, c. 14 x 12 x 6 cm

Vessel 2010, Carbon Trap Shino, 32 x 14 x 14 cm

Vessel 2015, Carbon Trap, 35 x 15 x 15 cm

Blossom Jar 1985, Gas fired, 30 x 25 x 25 cm