OMAGH RAILWAY STATION

Tony McGartland

Tony McGartland

Chapter 1: The formative years of the GNR (I)

Chapter 2: War, Strike, Derailments and Tragedy

Chapter 3: Excursions from Omagh

Chapter 4: Omagh – a 24/7 station

Hill, holding her young son Robert and watching a Belfast bound train leave Omagh in 1951. Edith’s husband Bill started with the GN as an engine cleaner, progressing to shunter and driver in town. He drove the daily railcar service to Portadown. His brother Joe also started worked on the railway in Omagh as a boy porter, progressing to a shunter. Many families like the McGrews were employed by the railway, the Crawfords, Donaghys, Donnellys, Kerrs, McGirrs and many others who lived in houses that overlooked the railway. Photo source: william mcGrew

her home

The ‘Londonderry and Enniskillen Railway’ was formed and incorporated by an Act of Parliament in July 1845. The line had already been surveyed by George Stephenson in 1837 and he estimated that the connection would cost £310,000 but the shareholders felt it could be done for less. They subsequently wrote to Dundalk born Irish engineer Sir John MacNeill and the line was surveyed again. When a disagreement about the route between Strabane and Omagh could not be resolved, George Stephenson’s son Robert was brought in and he submitted a revised costing and the contractor James Leishman started work. The first stretch of line between Derry and Strabane finally opened for business on 19th April 1847.

In the summer of 1852, when the line was approaching the outskirts of Omagh, a train carrying only inspectors, directors, solicitors and contractors for the company were taken to examine the line. They were keen to see what progress was being made. Soon after, on 13th September 1852, the first passenger train left Omagh Station for Derry. Initially a temporary station made of timber was erected for passengers but this was never suitable, as it was on an embankment with a steep slope up to the station. The approach to the

station was difficult and passengers had to climb steps to access trains. To begin with, passenger traffic was light and only four-wheel carriages were used, pulled by small locomotives. The local press carried the first advertisements announcing the opening of the rail services between Derry and Omagh with trains leaving Omagh daily at 4.45am, 8.30am, 11.00am, 3.00pm and 5.00pm with a journey time of almost two hours.

From 1904, the original ‘Railway Bar’ was situated in John Street, previously known as the ‘Railway Tavern’. It reopened its doors under a new licence in February 1960 at Railway Terrace managed by the Campbell family originally from Dromore, Co. Tyrone.

For some years this situation continued, with passengers having to enter and exit carriages from this temporary wooden platform. All trains were dispatched from the single platform and line, leading to much disruption and delay. This was remedied sometime after when engineers improved conditions at the station. They raised the ground levels around the entrance with tons of soil to allow passengers to board trains with ease and also added a second platform and shelter.

A very rare shot of PP Class 4-4-0 No. 106 Tornado approaching Market Junction in 1910. Like many GN engines, No. 106 lost her name in 1914 and went to CIÉ in 1958, to be withdrawn in 1960. The timber platform and balcony around the signal cabin were destroyed by a derailment several years later. This was a ‘check’ platform, where trains would stop for passengers’ tickets to be checked in the days when carriages had no through corridors. By 1932 the cabin was removed entirely and replaced with a ground frame to change the points for the Market Branch. On the left a member of the permanent way staff holds a 5’3” track gauge, the standard measurement of the Irish broad gauge line, measured rail to rail, and the strange looking apparatus in the foreground is a catcher for the single line staff as the train enters this section of track.

At the time the local press reported that ‘the people of Omagh were now able to enjoy the comfort and convenience of rail travel.’ So much so that in the years that followed the ‘Lough Erne Steamboat Company’, in conjunction with the ‘Londonderry and Enniskillen Railway’ company, were carrying passengers on their ‘People’s Excursion’ specials leaving Derry for Enniskillen at 7am. The trip included sailing on the new Lough Erne steamer ‘The Countess of Milan’, down Lough Erne. The company advertised services in the local press with four departures daily from Enniskillen and similar return trips from Derry. The return ticket cost 1”/6’ with an additional 6pence for passengers wishing to join the cruise. Since there were no rail connections with Omagh, the people of Dungannon were enjoying ‘Pleasant Excursions’ to the seaside at Rostrevor. During the summer months of 1862, the ‘Irish North Western Railway’ provided a special train

from Enniskillen to a ‘Grand Musical Fete at Portrush’. Passengers from Enniskillen via Omagh travelled to Derry and on their arrival at the city made their way across to the Waterside Terminus of the ‘Belfast and Northern Counties Railway’ where they continued their journey to Portrush. Several flute bands provided the music on the day. This continued for several years until everyone was able to enjoy the pleasures of County Donegal as work had begun on the 43 miles from Bundoran to Enniskillen, also linking the Atlantic coast with Derry. Initially, the plan was to connect Sligo, Bundoran and Enniskillen but after some delay in its construction, the rival ‘Sligo, Leitrim and Northern Counties Railway’ was approved by parliament and the ‘Enniskillen and Bundoran Railway’ (E&BR) company abandoned their plan to extend to Sligo. Bundoran was connected to the growing network of railway travel when it opened its station on 13th June 1866.

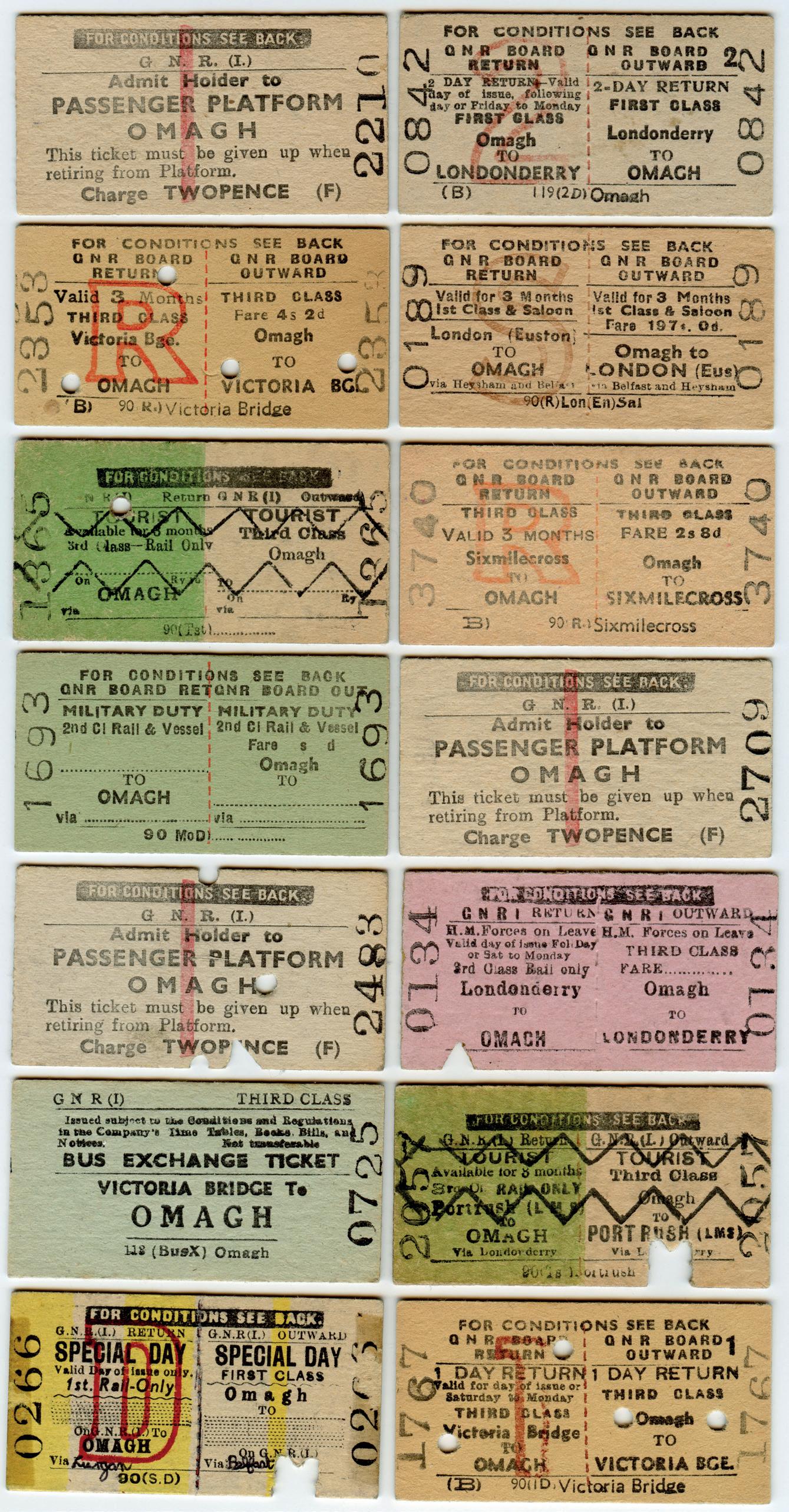

A mixed selection of tickets for trains leaving and arriving at Omagh from both GNR(Ireland) pre-1953 and GNR(Board) 1953-1958. After the GNR(B) was dissolved, UTA appeared on all their tickets from September 1958. This type of railway ticket was introduced by Thomas Edmondson in England in the 1840s. Today similar tickets are much sought after by railway collectors. One of the most desirable tickets being the last passenger train to leave Omagh.

Several hundred people travelled by train to Buncrana in August 1891. When they reached Derry, they were treated to a selection of music from ‘St. Eugene’s Temperance Society’ Band. Later, they travelled on to Buncrana and enjoyed the splendours of the coastline and chance to walk around the village. The party returned to Derry at 6.30pm and the band played up Foyle Street before making their way to the railway station where a crowd had gathered and treated them to loud applause as the train left the station for their return journey to Omagh.

Royalty also enjoyed the pleasures of rail travel. When on his way to Derry from Dublin, His Royal Highness Prince Arthur travelled on the ordinary 10.20am mail train on 28th April 1869. When he arrived at Enniskillen, he was greeted by Mr. Pemberton, locomotive manager of the Irish North Western Railway, who had a special engine decorated for the occasion, waiting at the station to take His Royal Highness on the remainder of the journey. The train stopped at Omagh where a guard of honour of the ‘Royal Tyrone Militia’ was stationed. Colonel Caulfield, who accompanied his Royal Highness on the tour, left the train with Prince Arthur, and both men walked up and down the platform inspecting the soldiers.

The then Prince and Princess of Wales (later to become King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra) travelled by Royal Train on the GNR(I) from Dublin to Belfast on 24th April 1885. The following day, they travelled on the GN from Derry (Foyle Road) to Newtownstewart with stops at Strabane and Sion Mills. After a brief stay with the Duke of Abercorn at Baronscourt, they travelled from Newtownstewart to Larne Harbour with stops at Omagh, Dungannon, Cookstown, Castledawson, Templepatrick and Carrickfergus.

On 1st September 1897, the Duke and Duchess of York (later King George V and Queen Mary) arrived in Omagh as part of their Royal visit to Ireland. The Royal Train had made its way from Dublin and crowds of people lined the platform awaiting their arrival. The couple did not leave the train but several officials were permitted to board the train to greet them. One

of them being Mrs. Margaret Jennings, a member of the refreshment room staff, who shook the hand of the late King Edward. They continued on their journey to Newtownstewart where they were taken from there to Baronscourt Estate. The town was decorated with flags and buntings and a triumphant arch was erected over the main street bearing the greeting ‘Céad Míle Fáilte’. On their arrival at Baronscourt they were met by the Duke of Abercorn.

There were a few Royal Trains during the troubled years of the 1920s, including a visit on 22nd July 1924 when the Duke and Duchess of York (later to be King George VI and Queen Elizabeth) travelled from Belfast (Great Victoria Street) via Omagh to Newtownstewart for a visit again to Baronscourt.

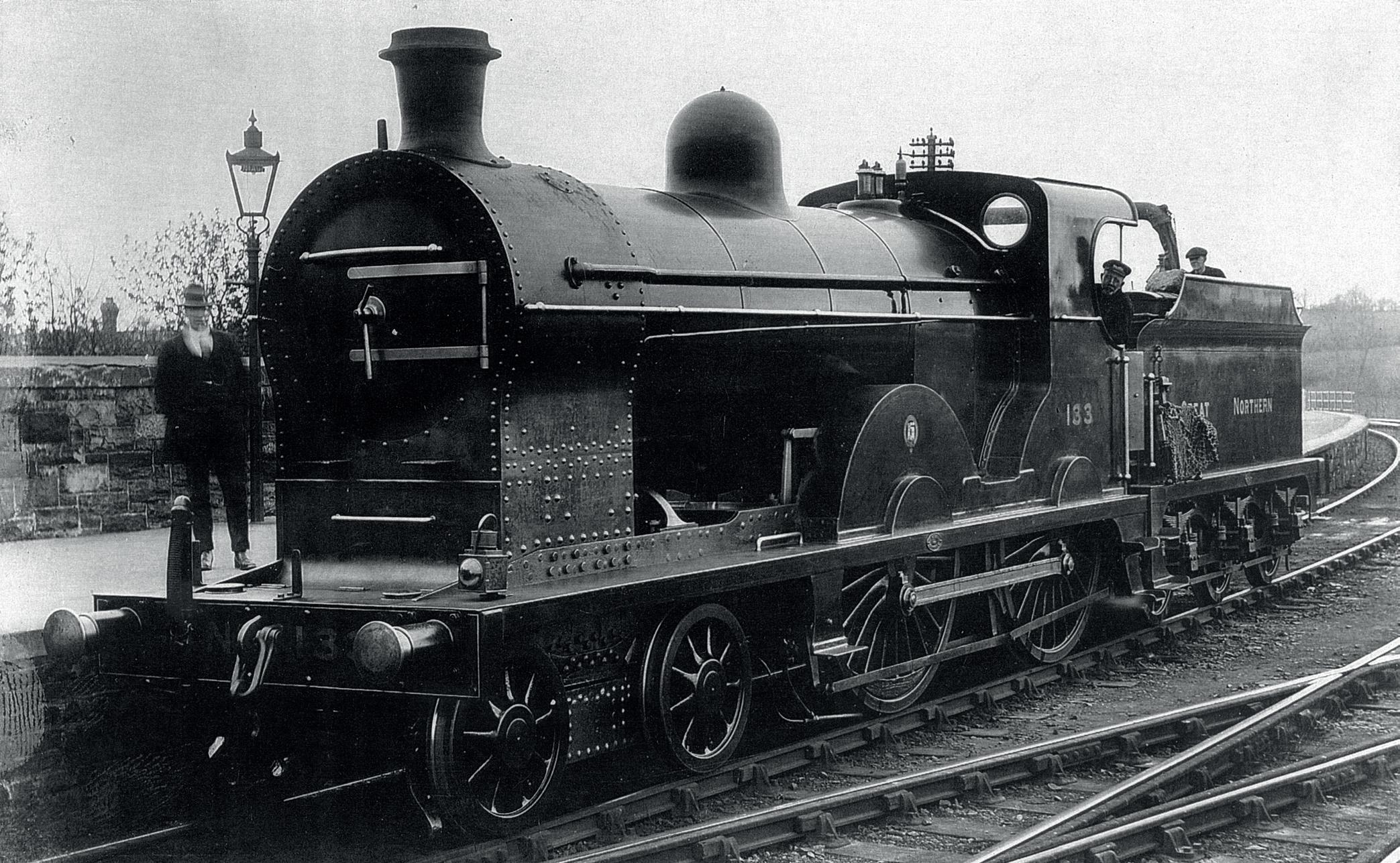

Qs Class 4-4-0 No. 133 taking water on the south end of Omagh up platform at Omagh pre-1928. The engine was built in 1899. The ‘Great Northern’ lettering on the tender was first introduced by Glover in 1913 and the smokebox door has handles rather than a wheel, suggesting that this picture was taken around 1920. Engines which frequented the ‘Derry Road’ were fitted with a staff collecting apparatus which was used when the engine was travelling at speed. Photo source: D.t.r. henDerson/ charles P. Friel collection

Passengers travelling on the GN could make use of luggage and parcels labels to prevent their belongings going astray. All labels shown are pre-1953.

Passengers travelling on the GN could make use of luggage and parcels labels to prevent their belongings going astray. All labels shown are pre-1953.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century the Great Northern Railway maintained a tried and tested routine in Omagh. Local services operated to Dungannon and Portadown to the east and Strabane and Derry to the north. Main line services north and east connected Foyle Road station, the GNR’s Derry terminus, with Omagh, Portadown and Belfast; and to the south Enniskillen, Clones and Dundalk with connections there to Drogheda and Dublin. Heavy goods traffic characterised the line as might be expected. As well as cement, grains, agricultural products, household and hardware supplies and coal. Special traffic such

as cattle arrived from many rural stations and textiles passed through the station daily from Herdman’s Mills in Sion Mills all passed through the station. Since Omagh was by now a junction, much shunting was necessary.

Examination of timetables and patterns of locomotive and staff rosters indicate that the station had 24-hour operation, seven days a week, almost until it closed. Special passenger trains included those organised for holidaymakers to Bundoran, reached by a branch line off the Omagh-Enniskillen section.

The driver prepares to ease off as the engine approaches another river crossing at the Linn Bridge and the pointwork of the Market Junction, the scene of many derailments. The stretch of water between the bridges was where American soldiers stationed in Omagh during the Second World War would learn to swim. After the war, local people used it as a popular place to swim during the summer months. The three arch stone bridge, just outside of town, is still intact today though is only used by farmers to access fields beyond. The new Cranny link-road runs parallel to the bridge near the new Omagh Hospital complex. Photo source: Drew DonalDson /charles P. Friel collection

An SG3 Class 0-6-0 engine hauls the 7.15pm goods train crossing the Camowen River at Cranny. This bridge is often mistaken for the nearby Leap bridge which carries the Donaghanie Road over the river further upstream. PP Class No. 12 at Omagh just prior to the closure of the Enniskillen line in 1957. Like many of the same PP class engines, they were found in daily service on the Bundoran line. The engine was built by Beyer, Peacock in 1911, went to CIÉ in 1958 and was withdrawn the following year. Photo source: author’s collection

A view of the south cabin taken on 19th March 1961 with the up-platform starter signal for Beragh to the left of the cabin. Both sidings on the closed Enniskillen line are backed up to the buffer on the Dromore Road with goods wagons. Railway Terrace can be seen behind the cabin with the Railway Bar on the left gable, a popular place for staff of the station on a Friday evening. Photo source: J.D. FitzGeralD/charles P. Friel collection

Ex-NCC W Class 2-6-0 No. 98 ‘King Edward VIII’ on the 5pm relief to Belfast on 8th July 1961. The engine was built in 1937 and saw most of her service on the NCC lines between Belfast York Road and the North Coast. Seven of these moguls were transferred for use to the Derry Road, though by then they were pretty much worn out. To the left, passengers on the down platform wait to board the 2.45pm Belfast to Derry worked by S Class 4-4-0 No. 61 ‘Galtee More’ (ex-GN No. 173) with a parcel van attached to the rear. Parked in the bay on the right are a 20-ton brake van, 4 plank open wagon and a 10-ton closed goods wagon. Photo source: J.D. FitzGeralD/charles P. Friel collection

A view of the south cabin taken on 19th March 1961 with the up-platform starter signal for Beragh to the left of the cabin. Both sidings on the closed Enniskillen line are backed up to the buffer on the Dromore Road with goods wagons. Railway Terrace can be seen behind the cabin with the Railway Bar on the left gable, a popular place for staff of the station on a Friday evening. Photo source: J.D. FitzGeralD/charles P. Friel collection

Ex-NCC W Class 2-6-0 No. 98 ‘King Edward VIII’ on the 5pm relief to Belfast on 8th July 1961. The engine was built in 1937 and saw most of her service on the NCC lines between Belfast York Road and the North Coast. Seven of these moguls were transferred for use to the Derry Road, though by then they were pretty much worn out. To the left, passengers on the down platform wait to board the 2.45pm Belfast to Derry worked by S Class 4-4-0 No. 61 ‘Galtee More’ (ex-GN No. 173) with a parcel van attached to the rear. Parked in the bay on the right are a 20-ton brake van, 4 plank open wagon and a 10-ton closed goods wagon. Photo source: J.D. FitzGeralD/charles P. Friel collection

Omagh General Station was on the arterial railway route to the North West of Ireland connecting it’s capital Dublin with the port of Derry. For many decades the town also served as a busy junction to another important line from Enniskillen and In its heyday the station might be busy for more than 22 hours out of 24. When the Derry Road closed in 1965, not only did Omagh lose its railway but the town lost a sense of community - of railway families who for generations lived in houses that surrounded the railway and provided steady employment. This book brings together the history of the railway in Omagh – researched over many years and told by railway staff who worked the station.

For anyone who lives in Omagh and beyond, with an interest in Irish railways, this is the first and only book that documents the history of the towns passenger and goods station and is presented here with over 140 images, many of which have never been published before, captioned in great detail by the author. The book is a vital part of every railway enthusiast’s collection and serves as a reminder of Omagh’s importance in railway history.

The Transport Treasury

The Transport Treasury

Price:- £18.95