Author: Lois Olive Gray

Photography: Kay EllenGilmour, MD

Photo Album: www.kaygilmour.smugmug.com

INTRODUCTION

There are many poetic names applied to this most beautiful country Land of the Thunder Dragon being the most famous and Shangri-La being the most favorable. In addition, during our visit there we thought of some descriptive titles of our own The Cloud Kingdom, The Quiet Dragon Land, and Valleys High being our own favorites. However, in the spirit of our frolicsome adventure there, I decided to name this chapter for our most unsettling experience in the nation. Though English has one of the largest vocabularies of earth’s languages, even all its many adjectives cannot really convey the astonishing beauty of this tiny kingdom, lost in time among the majestic Himalayas. The country cries out for photographers and I was lucky enough to be traveling with three excellent ones. So while I struggled with my lack of adequate words to express the glory of the landscape, they aimed their lenses at everything sky-aspiring mountains, velvet green valleys, torrential glacial rivers, small, tidy farms, sleepy towns, two & three story homes with the most amazing window and door-jamb designs, sturdy temples blazing with golden tops, colorful birds, flamboyant flowers, dense virgin forests, amazing insects and the wonderful, friendly and handsome Bhutanese people.

Many people, with no idea where this remote tiny kingdom is located, know that its monarch has declared his intention to measure the success of his governance, not by the Gross National Product but by its Gross National Happiness! By their own criteria, King Jigme Singye Wangchuk and his son the present King Jigme Khesar Namgyal Wangchukin have achieved a triumph beyond their own daring. Several international organizations measure various societies according to many different parameters, but all find in surveys over the years that Bhutanese people are the “happiest” on earth! The four goals for attaining a high GNH score are: 1) promotion of equitable and sustainable socio-economic development, 2) preservation and promotion of cultural values, 3) conservation of the natural environment and 4) establishment of good governance. In our 10-day visit, we saw and were impressed by this country’s commitment to these goals. Evidence of their efforts will be revealed as the story of our visit progresses.

COUNTRY FACTS

To begin, let me recall some of the fascinating facts about Beautiful Bhutan. The country is landlocked by India on three sides and China on its northern border. It is relatively small in size, 36,420 square miles--Florida is 65,728 sq. miles. Its population is small, around 700,000, with a median age of 20. Life expectancy for Bhutanese people has reached 61 years for males and 64 years for females.

The ethnicity of Bhutanese people is divided among three major groups: 50% Bhotes (people of Tibetan origin who migrated into what is now Bhutan in the 9th century), 35% ethnic Nepalese people who came much later probaby lin the 18th century, and 15% the indigenous peoples (3 main tribes) of Mongolian heritage whose origins are unclear but whose entry into the land is generally held to be around 2000 B.C. The Nepali and Tibetan peoples are pretty completely intermixed, but there has been relatively little intermarriage with the indigenous peoples by the other Bhutanese.

RELIGION

In religion, 75% of the peoples are Buddhists and Buddhism is the state sponsored religion. The remaining 25% are Hindus. There are elements of animistic practices among the indigenous peoples as well as their being intermixed with Buddhism and Hinduism. Only Buddhist temples are permitted in the country, but the Hindus are not suppressed in their religious practices. The King participates in both Buddhist and Hindu rituals and holidays.

Many Buddhist temples contain statues of Hindu gods and goddesses, like Ganesha and Lakshmi; therefore, many Hindus feel quite comfortable in those temples. After all, Buddha reached enlightenment among the Hindus of India and preached his first sermon in Sarnath, India! Buddhism penetrates every aspect of a Bhutanese life. They are devout and deeply spiritual. Buddhism determines names given to children, dates of acceptable marriage, chosen partner for marriage. Houses are blessed by religious figures on a yearly basis.

Prayer flags are everywhere. No Bhutanese person would pass a prayer wheel without twirling it. Offerings are made regularly in the temples by the common people. The very land itself is considered mystical and sacred because lamas and holy men sat under this tree, or created an impression in stone with their bodies over there, and monasteries are situated like eagle’s aeries on high mountain shoulders overlooking the valleys because a holy man meditated in a cave there or had a vision on that craggy outcropping. The lamas and gurus who brought Buddhism to Bhutan are venerated but also seem as real to the people as if they were living in the land today. Thus, echoes of its past are actually very present in Bhutan today.

GOVERNMENT

For the immediate present, the government of this country is an absolute monarchy (with power shared somewhat unequally between the King and the Je Kempo, national head of Buddhism). However, in 2008 the country will peacefully transform itself into a constitutional monarchy with a legislative body elected by the people. At present, the King’s advisory council is appointed by him as are all other officials, including judges. There is a National Assembly elected by the people, but its power at present is very limited. This monarchy is only 100 years old, having been formed under pressure from the British in 1907. Prior to that time, the country was divided into several hereditarily ruled districts led by constantly contentious warlords. The British wanted stability in Bhutan as a buffer between China and their own colony, India. They strongly suggested that the richest and most powerful of these warlords (the Wangchuks of Trongsa district) become the leader of a centralized government.

Surprisingly, the Bhutanese people agreed peacefully to this suggestion and the first monarch was crowned. He had authority over the internal affairs of the country while Britain control foreign relations and provided border security. In l947, when India gained its independence from Britain, it assumed the same relationship with the Bhutanese government. Even today, India supplies 3/5s of Bhutan’s operating budget and military protection of the borders. Since l971 (when Bhutan won admission to the United Nations) it has been fully

independent in foreign affairs as well as internal governance but it is very much in the interest of the Bhutan government to remain on friendly terms with India because of the monetary dependence and because India is its major trading partner.

The 4th King of Bhutan astounded his fellow citizens, and the world, when he abdicated at age 42 in favor of his young son, the as yet uncrowned 5th king. He informed his people that he wanted the government to progress to democracy with a constitution. He believed that a younger man could be more forward looking and could more easily carry out this design.

His young son has been ruling the country since that time (about two years ago). It is planned (with Buddhist blessings) that the transition to a constitutional monarchy will occur in 2008 along with the king’s coronation and the election of a truly representative assembly with legislative powers. The people consider the year and the celebrations auspicious, both religiously and historically, since 2008 will be the 100th anniversary of the monarchy. Kelzang, our guide, expressed great confidence in the wisdom of the young king and his optimistic father because they have already demonstrated their excellent governance and their concern for the Bhutanese people. He is pleased that the newly crowned king will initially have greater power than in a traditional constitutional monarchy because he believes that it is right that the complete transition should take place gradually In most of his talks with us about the government,

Kelzang described the kings of the country as rulers with the good of the people always at heart. He approved the government’s avuncular role (maybe even paternalistic) in creating laws that protect the people from mistakes and harm, such as forbidding the housing of livestock on the lower floor of their homes as was the practice in the past and in forbidding the top attic floor being used as a hayloft because of fire risk. He liked the fact that government requires childhood vaccinations (as well as paying for them) to prevent disease in the population.

He was very much in favor of the government control of logging in the country, for the preservation of the virgin forests and the valuable trees for all the Bhutanese.

He was much in accord with the king’s requirement that all returning students who have been studying in other countries participate in a reorientation program so that they will not forget the traditions and practices of their own country. He even professed himself to be comfortable with the royal decree that Bhutanese men and women wear their national dress when acting as representatives of the country, even in casual ways. Probably his view is shared by most of the people who will feel more confident if the king continues to make the big decisions that affect the welfare of his people their Gross National Happiness at least for a while longer.

We had 10 days to explore this happy and beautiful country and we wanted to see everything possible during that time. We climbed to monasteries sitting out on rocky precipices, struggled spraddle-legged across many swinging bridges, climbed awkward stiles, remove our shoes to enter temples and their sacred domains, sampled the fiery Bhutanese specialties (everything is cooked with the ubiquitous chili peppers always decorating the rooftops of the homes while they are drying), sought repose in surprisingly comfortable and luxurious hotels, gaped at sublime landscapes, and attempted to learn something of the amazingly convoluted history of the country and its unique practice of Buddhism.

We enjoyed the company of a charming and educated young guide, Kelzang, and our excellent driver, Tschering, a man with 15 years experience in driving the treacherous roads of Bhutan and Northern India. He was completely unflappable and never frightened us even once!

ACCIDENTS

So how did a burro get into the story? He actually appears during the first full day of our stay in Bhutan.

After having flown through the alarming mountain maze that the airplane must thread to reach the 6000 ft. Paro Valley, we had one night to rest before beginning our first hike to the 13,000 ft. Tiger’s Nest Monastery. However, our dreams that night were filled with the memories of the glorious views we had of Mount Everest on the flight in. The mountain was in clear view no clouds hiding its lofty head against a bright blue sky. What a view to excite the imagination and enter the soul of any lover of mountains!

The Paro Valley is a narrow defile and the low hillsides seem almost to touch the wings of the Drukair plane as we passed. The hanging rags of clouds decorated the valley but also added to the suspense of the approach to the airport itself. But the pilots for the national airline are experienced in this approach and do it twice daily. So we relaxed and enjoyed our Everest scenery

Anyway, back to the burro! The next morning after arrival, we three women awoke to begin the climb to the Tiger’s Nest. Dan had arrived from Tibet feeling a tad under the weather and had decided to rest at the luxurious Uma Hotel rather than exhaust himself with the climb. We reached the staging area where the hike itself begins at about 9:30 a.m. and started out, filled with happy anticipation (Micki) and some anxiety (Kay & Lois anyway).

The way up was steep but the scenery was lovely and we were charmed by the prayer flags and the prayer waterwheels we passed. However, it became clear pretty quickly that Kay and I were not enjoying the climb at all.

We were breathless and exhausted long before we should have been. The altitude really punished us. When we reached the little restaurant about two/thirds of the way to the top, we told Micki that we were most definitely not having any fun and had decided to wait for her and Kelzang right there with the wonderful views of the monastery. Micki, having come from the base camp of Everest in Tibet just the day before, was fully acclimatized and had no trouble at all completing the ascent to the Tiger’s Nest. After Micki and Kelzang headed off to finish the hike, Kay and I decided to walk on up at a slow pace on our own.

We had completed a couple of switchbacks upward when we heard thundering hooves. We knew that tourists and pilgrims could make the ascent atop small mules/burros but that no one could descend on their backs. The animals would be riderless we knew; however, we assumed they were under the control of the guides or wranglers.

Where we were at the time of our burro encounter was at a divide in the trail around a little hill of rocks. We hurriedly climbed up the coarse granite hillock, assuming that the burros would flow around us as they continued to descend. That is not how one of the animals saw his path at all! He decided to come right over the granite rocks and go straightaway to grazing on the trailside. He jumped up and scrambled over the boulders coming directly at Kay. His shoulder caught her backpack and lifted her completely off her feet. She fell but luckily was not trampled by his flying hooves. However, she rolled down the hill and landed face down on the gravelly trail.

The “attacking” burro was by that time calmly grazing on the vegetation that lined the outer edge of the trail (those bushes and shrubs prevented Kay from rolling on down the hillside).

All this happened in slow motion, of course, and by the time Lois had clambered down to reach her, Kay was already assessing the damage to her person. She was very lucky indeed because she had not broken any bones; however, she looked as though she had been knocked over by a burro! Her face was scraped deeply and her glasses were bent quite out of alignment. Her right arm had been torn and almost skinned by the rough granite from elbow to wrist.

She had smaller cuts and gashes on her other arm and her legs were badly bruised. After realizing that she was not broken, she was terribly anxious about her camera which took some of the brunt of the fall too since it was secured at her waist on the belt she was wearing.

It was fortunate that we had brought the first-aid kit along on the hike because we were able to wash all the cuts and open places clean of dirt and gravel with soap and water. Then we applied an antibiotic ointment to all the raw areas and covered them with gauze.

By this time, the Bhutanese handler arrived and figured out something untoward had happened though whether he ever knew exactly what is problematic. He spoke no English and of course we spoke no Drongzah. At first he seemed to be offering Kay a ride on one of the burros but we knew that was not usual. Then it appeared that he wanted her to punish the burro by socking it in the jaw. That

seemed a foolish thing to do since it would not change anything; the animal had not deliberately attacked her, and she would probably have gotten a swift kick for her pains. We finally got him to go on down the hill with his three burros and we could only hope that he exacted no reprisal on the burro.

Slowly we descended the trail ourselves and then were content to wait at the cafeteria for Micki and Kelzang. They were pretty shocked when they saw how beaten up Kay looked but she was really all right despite the trauma and the shock of her meeting with the burro. So we all completed the hike back down listening to Micki’s triumph on the trail up to the Tiger’s Nest. We were very proud of her and happy that she had made the entire trek.

The Tiger’s Nest is a beautiful monastery with a breathtaking view of the Paro Valley another reward for the climb.

The next day, Kay was pretty sore but surprisingly quite well. In the ensuing days, we were very pleased to see that she never suffered infection in any of the sites and her camera seemed to be functioning normally. Quite an eventful first day in the country for sure! And it certainly wouldn’t be our last fascinating day there.

On the 3rd day of our Bhutanese adventure, I was the accident victim. This time, no manic animal could be blamed for the mishap. It was my own loss of attention. We climbed to the Tango Monastery outside Thimphu on a beautiful morning and all of us felt terrific; Kay & I were over the jet lag and had acclimatized sufficiently to enjoy a hike to 10,000 ft.. Dan was over the malaise he had brought from Tibet and ready for an invigorating walk in the pine forests up to this home of the 12th incarnation of one of the Bhutanese lamas. He is currently 15 years old and he did not give us an audience despite our march to his home.

Monks were taking a holiday and we met many of them coming down the path towards their town visit. Buddhist faithful families were climbing up with us to

make sacrifices and perform prayers at the monastery. The trails were busy and colorful with flowers and beautiful red- orange monk robes, and many manifestations of the national costume on the ladies and gentlemen carrying babies and tending youngsters. It was a wonderful day and experience to be sharing with the Bhutanese people.

We enjoyed the climb and were entranced with the wonderful people and the stunning Tango Monastery itself. The monastery was built on the high mountain terrace because a lama had a vision here as he rested on his trip from Tibet.

He dreamed that a horse would appear who would carry him on the remainder of his travels and he saw the horse’s head clearly in his dream. Tango means Horsehead in Drongzah. The monastery has another claim to uniqueness as well. It has a rounded outer wall to the main building The windows are framed like the other such structures in the country but that semi-circular wall is a singular piece of construction. The whole experience of the climb and seeing the beautiful monastery had us all bubbling over with enthusiasm as we descended in laughter and joy. Less than 50 feet from the bottom of the trail where our van awaited us, I got to talking too enthusiastically, forgot about my footing, and slipped on a very muddy patch in the path, twisting my ankle really badly.

I gimped my way to the van and Kay used more of her first aid materials to bind my ankle, hoping to reduce the swelling that was sure to come. I took aspirin and kept the hiking boot on, again with the hope that the swelling would be less. Then we drove on into Thimphu for more sightseeing. I wish I could report that my inattention was no more troublesome than a little discomfort and some slight puffiness but that would be less than candid.

Unfortunately, a very severe sprain was the result and the disability it caused me continued throughout the trip. Walking up steps was actually the easiest part of the trip, hiking the next least problem, but going down steps was a misery because my ankle was weak and very painful on the downgrades. As I was to learn to my sorrow, so much of sightseeing in Southeast Asia is climbing up and down stone stairs to visit temples, monasteries, museums, ruins, hotels, restaurants, getting into boats. It really was an inconvenience of the first water, but it could have been so much worse like a fracture. So I didn’t complain and refused to let it stop me from going anywhere and everywhere anyone else did.

ARCHITECTURE

We were surprised to see how different the building style in Bhutan is compared to what we had seen in Nepal, Tibet and India the nearest influences. Typical Bhutanese homes are two or three storeys, made of bamboo, mud and bricks with an overlay of stucco. The houses are usually white or beige and often have complicated paintings of mythical animals, phalluses, demons, and flowers decorating the outer walls. All houses have elaborate external window and door treatments, with enlarged frameworks surrounding the openings.

Those frameworks are wooden constructions of angular design and bright colors. The uniformity of this architectural style is quite striking; the impression is quite unlike our country, where you might have a log cabin next to a colonial, or a federal style sitting close by a rancher. Each Bhutanese home, whether old or a just built apartment dwelling, will have a room or portion of a room dedicated to a chapel where statues are displayed, prayers are said, and offerings are made.

Another curious discovery we made was that each dwelling place, even those without indoor plumbing in the country, have a little anteroom which is a latrine area however, it is used only religious figures when they visit for the annual blessing of the home or if they are summoned because someone is ill and needful of blessings and prayers.

Monasteries, temples and dzongs share these characteristics too so they add to the organic appearance of the Bhutan architecture; all the buildings look as if they belong here and nowhere else. The dzongs are structures unique to Bhutan and reflect the close alliance of political governance and the Buddhist religion. Each of the twenty districts of Bhutan is administered by a local governor (penlop) whose offices are housed in half the dzong. Theother half of the building contains the religious authority and a monastery. The doublepurposed building thus demonstrates the dual nature of Bhutanese governance.

These buildings are impressive in size compared with other structures in their districts. They share the ornate window treatments and the construction style. The walls are very thick and taper inward as they rise. In addition, they are crowned with shining, gold or brass, multi- layered roofs with pagoda-like projections from the topmost portion. These buildings are always covered in white stucco.

No paintings adorn their exterior walls. Inside the religious portion of the dzong there is always a temple that can only be entered barefoot. Local citizens, both male and female, must also add a shawl (for men) or a wide ribbon (for women) to their official costume in order to go inside the temple. There is always a complex altar, sometimes with representations of the Buddha in one or more of his many incarnations, or of a local divinity, or of the bringers of Buddhism to Bhutan, as well as of important saints and lamas. There are always candles, flowers, and water vessels adorning these altars.

Most of the dzongs also contain a monastery with a school for the education of young people who wish to be monks. Housing for the monks and the students is also within the dzong compound. In the past, this monastery education was the only formal course of study open to young Bhutanese boys. Here they learned to translate the Sanskrit gospels and writings of the many religious figures important in Bhutanese life. They were taught the rituals, dances, prayers, and chants through which their devotion to Buddhist principles are demonstrated.

Even today, some youngsters are placed in these schools rather than the free public schools and they learn much the same things as their ancestors. Kelzang lamented the fact that the monastery education did not prepare the students for life outside the monastery community if they chose to leave on reaching age

We visited so many dzongs and temples that they all began to blend in our memories. Some have been more newly refurbished, some are more ancient and show their great age, some sit in the valley towns, others follow the twisting topography of a mountain ridge, one even floats on the point where two mighty rivers join in a tumultuous confluence.

The dzongs date from the 14th century but temples can originate from the 7th century. But since dzong and temple visiting is best “reported” in photography, I will not try to describe and name each of the wonderful edifices we visited. Suffice it to say, we admired the architecture and enjoyed the visits immensely and found each one intriguing, foreign, and in many ways mystifying as we are not really very conversant with Buddhism and its many myths and rituals.

Visits to two of these dzong-based monasteries provided deeply moving and revelatory experiences for us. At the Thimphu Dzong, we heard chanting and bellringing wafting across the central courtyard as we entered. We made some stops at paintings and statues so Kelzang could explain them to us but gradually the music became a strong magnet pulling us to follow the sounds. We were allowed to go into the temple (barefooted) but not to use cameras. We sat alongside the altar a little removed from it while a yellow-robed lama on a raised throne and his fellow monks in red were spread on the floor in rows in front of the altar, which was adorned with fruit, flowers and water vessels.

The monks were intoning in monotones while drums beat a cadence and the temples bells were jangling discordantly. Kelzang explained to us that the monks were saying special prayers for the head abbot who was in Bangkok undergoing surgery for a life-threatening condition. We sat on the floor with our legs folded beneath us (uncomfortable after only a short time) listening.

At last, the monks began using the strange “throat singing” we had heard before in recordings. At the same time, larger drums came out and the long (3 yards) horns whose bells actually must rest on the floor were sounded. The throat singing is very unusual and difficult to describe because it is so guttural yet musical. The tones produced are very low, much lower than the lowest operatic bass you have ever heard, and very throaty and almost growly.

But the ceremony must have produced something miraculous because as the cacophony reached its greatest stridency, a flight of pure white pigeons rose up from the courtyard and flew towards the heavens. Perhaps, the Chief Abbot was blessed with a successful recovery. However, of course, we would never know the actual outcome, but we preferred to believe that version of the experience.

The other wondrous experience occurred at the Jakar Dzong. We walked to the dzong as evening was coming on. In the large central courtyard of the monastery half, we saw some monks milling about, laughing and talking quietly. Then we saw the temple bells and the drums being brought out into the courtyard as the three groups of monks began to look on expectantly.

The monks were arranged in different ages: young children, teens, and young adults up into their 30s perhaps.

We realized that something unannounced was about to occur. Kelzang quickly ascertained that we had happened upon a rehearsal for an important religious festival that would take place in about three weeks.

First, the youngest monks performed their dances to the accompaniment of the bells and drums. They were charming in their intensity and determination to get the steps correct.

Occasionally, we could see one young fellow with an extra something in his performance, an agility or grace beyond that of the others. Then teenagers emerged from the dormitory and began their practice session. Of course, they were more polished than the children, but again there was a discernible difference in talent and enthusiasm among the youngsters. At last, the young adults were in the courtyard and then magic happened. They were swirling and posturing and performing the most complicated foot and hand movements and positions. Their faces were transformed with the joy of dancing and the fervor of their faith. The

dissonant musical accompaniment grew louder and more frenzied but the young monks kept pace and never lost their artistry. It was a truly moving experience to watch these devout men practice the time-honored dances with such elegance, ardor and accomplishment.

One of the most fascinating things about Bhutanese Buddhism is the fact that there is no Supreme Being in the religion Buddha is certainly venerated and respected for his spiritual achievements, but he is not worshiped in the sense that Christians understand worshipping their God. Rather, Buddha in all his guises is viewed as a supreme model and exemplar for human beings to follow in their own quest for Nirvana release from samsara the endless reincarnation cycle which returns all creatures to this world of unavoidable suffering. The only way to free oneself from this “wheel” is to attain enlightenment by following the precepts set down by Buddha and his many lamas and priests. These monastery festivals with music and dance bring devotion to Buddhist principles close to the people

and make real to them the teachings of the Buddha.

ARCHERY-THENATIONAL SPORT

Because the country is unique in so many ways, we were not surprised to find that the national sport is such a singular one: archery. There are two types practiced: 1) traditional bamboo bows constructed with natural materials available in the country and 2) modern composition bows (titanium, etc.) like those used in the Olympics. Teams are fielded by every village as well as by the bigger cities.

Archery contests occur every day in some part of the country. The “natural bows” and the “composition bows” are not used together in these contests however. The most amazing things about archery here in Bhutan are the diminutive size of the targets (about 1-foot square) and the distance between the shooting line and the target (from 100 to 150 yards)! A bulls-eye scores 3 points, hitting the target at all earns 2, and closest ground shot to the target gets 1 point. The teams and the spectators interact with much cheering and dancing when good shots are produced. There is always a scoreboard alongside the archery field to indicate how the shooting is progressing.

We were thunderstruck at the confidence teammates exhibit when one of their number is shooting

They stand right next to the target until the very last moment before the arrow arrives, only then leaping away. And remember, these archers are shooting at tiny targets ever so far away! Women do not shoot and it would appear that it is chiefly men who form the enthusiastic crowds watching the contests. We enjoyed observing archery contests in several towns and cities. It seemed to us that Bhutan should do very well in the archery competitions of the Olympics since they excel at these distances which are longer than those required in the Games.

WHAT ELSE MAKES BHUTAN DIFFERENT?

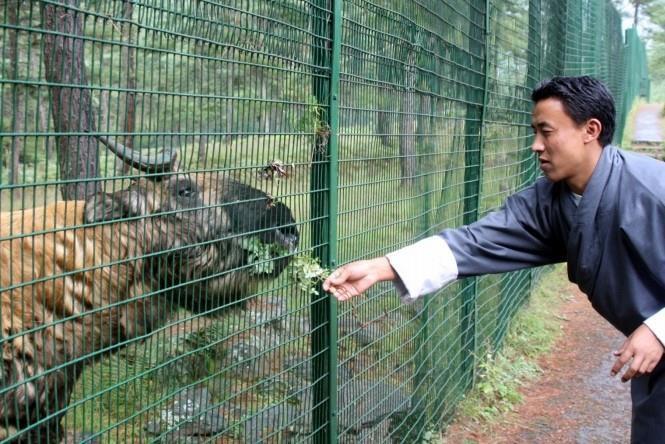

The national animal is the takin a bovine species existing nowhere else in the world. It looks a little like a bison, but it is smaller. The color of its coat is yellowishbrown and it is luxuriously curly. The takin’s face is rather sweet but not particularly intelligent looking. Both male and female have swept-back horns, though the males are quite a bit more formidable.

The takin is connected with one of the most important lamas in Bhutanese history: the “Divine Madman,” Lama Drukpa Kunley. It is said that he actually created the takin from the skeleton of a cow and the head of a goat one of his many miracles to convince the people of his powers. As a possible support for this theory of the animal’s origin, even today taxonomists are befuddled as to exactly where the takin should be placed among the cow-like and/or goat- like creatures, and some question if it is actually either one!

Males can reach 1000 pounds with females attaining weights around 600 lbs. In the higher mountains where the takin lives, he had been a food source for humans in the distant past, but killing them is now forbidden and that ban is easily upheld because of his association with Lama Kunley. There are very few left, however, because of habitat loss and changing climate. The government is taking steps to breed them in captivity for later re- introduction into their natural habitats. That program is what allowed us to see the creatures up close when we visited one of the government compounds where they are being raised. Other wildlife we were lucky enough to see were the unexpected musk deer with its long fangs in the upper jaw isn’t that a surprising thing? Deer with fangs?

The musk deer has a reddish coat and is about the size of the white-tailed deer we see in our own country. But those fangs do set him off as something pretty special. When we went to the Valley of the Black-Necked Cranes, we saw a red fox in the dwarf bamboo forest no black-necked cranes however. We were too early to see them arrive since they usually come in December. However, the fox was a wonderful substitute. He looked just like our own red foxes.

The antic Tarai gray langurs also made an appearance for us, along a roadside sitting on guardrails. However, as soon as we slammed to a stop for closer observation, they leapt into the trees that march down the steep mountainside. With our binoculars and long lenses we could view them easily anyway. They have completely black faces surrounded by a luxurious white ruff that makes them appear to be wearing large lacy collars, like the first Queen Elizabeth. Their bodies are covered with soft-looking, thick gray fur and the pads on their hands and feet are black like their faces. We observed them for quite some time as they dined on leaves and jumped from branch to branch with such elegant ease.

Bhutan also supports Himalayan Spectacled Bears, Snow Leopards, tigers, and martens, but we were never anywhere near where these rare and reclusive species would be found. There are small hut-like structures on stilts in many fields so that when monkey predation on the crops becomes too bold and too destructive, the farmer moves into the hut so that he can physically prevent their depredations.

Because of the Buddhist reverence for life, the monkeys and birds are not maimed or killed, merely frightened away. What Buddhist can be sure that the monkey he attacks is not a relative returned to life in a lower animal form?

INDIAN ROAD WORKERS

Despite being an agrarian, subsistence farming society for the most part, Bhutanese people have a decided dislike for the physically demanding work of road-building and pretty much refuse to take part in the constant roadwork going on in the country. The Bhutanese unembarrassedly believe that such work is beneath them.

For this reason, the government contracts with Indian companies which hire whole families of Indians living in the northernmost states of India, particularly Assam, to perform the necessary road construction and repair. These folks must have no prospects at all in their home states because they are eager to get these onerous jobs which pay so very little and offer such pitiful living conditions.

The workers are paid $2.00 a day and given only bamboo mats with which to construct their flimsy shelters. No food allowance is given as well as no health care or education for the young children who accompany their parents. The contracts are usually for 10 months after which time, the Indians must go back home. They are not offered any means by which to seek Bhutanese citizenship. The women work as hard as the men, often with very young children in tow along the roadsides where they seem in imminent danger of being run over. The basic work is the creation of gravel by smashing larger boulders and rocks.

What backbreaking labor, with little or no machinery to help! This is grunt work of the most basic kind and whole families are engaged in it. While we visited, it was really very hot and the roads were thick with dust so that the poor Indians were constantly breathing in air that must be filled with particles injurious to their lungs. What must their lives be like back in India that they would eagerly accept these jobs?!

More distressing still is the contempt with which these poor folks are considered and treated by the Bhutanese citizens. In all candor and with no shame whatever, our polite and considerate guide informed us that the Indians are just not equal to the Bhutanese.

One day he was telling us that when addressing each other, Bhutanese people customarily add the syllable “la” to a greeting when meeting others. For instance, when we met monks coming down mountain paths, Kelzang would say in Drongzah, “Good Morning, la.” He would use that construction in greeting both men and women. As part of our efforts to understand the place of the Indians in the Bhutanese society, we asked him if he would use that term of respect when addressing an Indian, either male or female, young or old. He looked thoroughly confused and a bit surprised but he answered, “Certainly not.” However, he became quiet and it appeared that he had never considered the implications of that “linguistic” condescension before! So Shangri-La does have a dark side after all; only the Bhutanese are entitled to participate in the Gross National Happiness.

TOURISM

Bhutan strictly controls tourism in its efforts to contain contamination from outside influences. By charging relatively high prices and requiring that all visitors have Bhutanese guides and drivers, the government restricts the number of tourists each year. In 2007, Bhutan would allow only 17,000 visitors in all. No independent backpackers such as Nepal has hosted over the years are permitted here. The plan is to permit 21,000 to visit in 2008! So we realized that we were in a very select group by being able to visit this marvelous place. It has only been in the last 15 years that television was allowed and foreign movies are still not shown in

Bhutan (it has its own movie industry to produce films for home consumption). Foreign movies are available to rent for home use. Of course, the Internet (there are many Cyber-Cafes all around the country) and the ubiquitous cell phones are quickly silting in the artificial “moat” that has protected the little skycastle kingdom for so long.

THE NATIONAL UNIFORM

The retention of and emphasis on the national costume is certainly one of the strands in the fabric of Bhutanese society that strengthens its amazing homogeneity. The man’s “goh” is a one-piece, short-skirted, rather kilt-like, outfit that also features long sleeves with very wide (usually white) cuffs. Fabrics are seasonal with lighter materials being used in summer and heavier wool cloth

used in winter. But, whatever the season, the men favor bright colors, plaids and stripes though gray and navy blue are often seen as well. The goh is fashioned from a single strip of cloth and is wrapped around the body, similar to the wrapping Indian women employ in securing their saris. The outfit is held in place by means of cloth belts of different designs but always wrapped very tightly around the waist to prevent unfolding of the garment. The ensemble is completed with long knee socks and shoes, usually a loafer-type in black or brown. The patterns on the socks usually have no correspondence with the colors of the goh’s fabric. The men, young and old, slim and a bit thicker, all look very well turned out in these uniforms. (In reality, we saw no overweight people in Bhutan and no really skinny ones either). Older men are usually heavier than young ones, but they have not run to obesity.

The “kira” is the dress of the women and it too is a garment made of one piece that is wrapped around the body and held in place by a belt. Two large brooches, usually gold in color, hold the shoulder sections in place. The biggest difference is that this garment reaches the ankle rather than stopping at the knee as the goh does. The women top their kira with a short, fitted jacket with long sleeves and cuffs. They too like bright patterns and embrace plaids and stripes most often with the jackets being made of a solid color. Both men and women can use their cuffs for carrying things or slip items against their torsos for ease of transport. Older women wear their hair cut fairly short and younger ones show ponytails or loose-hanging hair on girls. Men most often are seen sporting Western-style haircuts. Even little boys and girls heading for school dress in the national uniforms on Fridays. This practice lends further to the cohesiveness of the society.

Head coverings during the summer are pretty much non- existent but in the higher elevations we did see both men and women in knitted “toboggan” type caps. Occasionally, we would see both men and women working in the fields wearing an almost flat circular bamboo hat on their heads for protection from the very intense sunlight.

Bodily adornment, such as jewelry, does not seem to be very popular among either men or women. But older folks carry their “rosary” beads with them. Certainly, the monks do not wear any decorations at all and they keep their heads shaved. Even Buddhist nuns shave their heads and they wear robes of an almost maroon color. They are not seen on the streets very often and their temples are shadowy so it difficult to judge the actual color of their robes. Most men do not display facial hair, no beards or mustaches. It may be that they do not grow significant facial hair because we saw no men who appeared to have a “five-o’clock shadow.” However, it must be admitted that we did see a few very old men with stringy gray beards.

Monks wear wraparound deep red robes that are also skirts really. Even the young monks wear this habit. Their garment ends with a shawl-like affair over one shoulder, rather like an Indian sari again, which allows air circulation on hot days when one shoulder can be bared. Laymen often wear an undershirt so that the top part of the goh can be dropped to the waist for “air conditioning” the core body.

EDUCATION

From the start of the Twentieth century, Bhutan has stressed education and provides free schooling for all children for 11 years: All classes are taught in English isn’t that surprising? Passing national examinations is necessary for students to leave primary school and for graduation from senior high studies. Tertiary education is available in the country, but the government does not provide financial support for students to attend college. Most families with sufficient wealth send their sons to India for college or university education.

PERSONAL NAMES

The Bhutanese who live in the northern Himalayan valleys where we visited do not have family names. Many children are given names corresponding to their position in the family like second child, or third child. Most names are applicable to both male and female children. Monks choose the names to be given to newborns, usually by the seventh day of life.

We were surprised to learn that our guide and his fiancée are called Kelzang (meaning 3rd child). We wondered how the teachers handled classes filled with many 3rd children. Kelzang said it was easy because the teachers just add 1, 2, 3, etc. to the name and each child knows which one he/she is. In legal situations, the people are distinguished themselves by their birth dates. In the southern part of the country (where we did not visit), the people of Nepalese origin usually have two names with a family name in the Indian fashion.

WOMEN’S RIGHTS

Bhutanese women have equal status with men, unlike the status of women in most Asian countries. Women are the inheritors of property and wealth. They head the families and make the work assignments in the rural setting. However, that does not mean they escape the hard labor of agriculture and livestock tending. They are always seen in the fields alongside their husbands and sons. They control the family finances, but also must take care of the household and the children. So they are very hardworking indeed. Not too different from how many Western women see their roles jobs outside the home, but also total responsibility for the household and the rearing of the children

NATURAL RESOURCES

The most lucrative resource the country boasts are the rivers thundering down mountainsides creating hydroelectric power m u c h o f which is sold to India. More power plants are under construction for this source of hard currency, though the majority of rural people have no electricity at all. Timber, gypsum, and calcium carbonate are other natural resources with export commercial value. Logging and mining are strictly controlled for the preservation of the natural environment.