6 minute read

Margaret Craighead

Advertisement

outdoorpioneer A modest pioneer

Margaret Craighead avoided accolades but had a big impact accolades but had a big impact

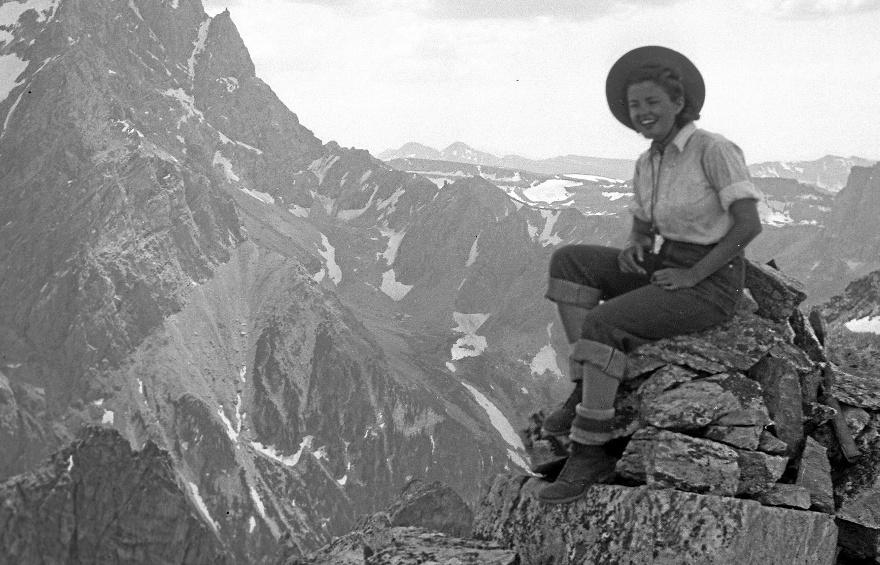

Margaret “Cony” Craighead poses high in the Tetons in this undated photo.

CHRISTINE PETERSON

For the Star-Tribune I t was the early 1930s in northwest Wyoming, and Margaret Smith was up for just about anything. She’d spent summer after summer living in tents with her mother and father. She knew every climber in the area, most scientists in the region and even as a little girl collected specimens that populated Park Service visitor’s centers.

She and three other women became the first all-female group to summit the Grand Teton – the first “manless” trip it was called at the time. And she went on to complete a number of other first ascents in the area.

It was logical, then, that she went along with her dad, a summer ranger in Grand Teton National Park, to check on a report of two boys with birds of prey. The boys – twin brothers named John and Frank Craighead – had falcons in the back seat of their used Chevrolet. They were falconers. And John would one day become Margaret’s husband.

She was a woman who climbed so much she earned the nickname “Cony” after a common name for the pika. But she didn’t, according to her son, Johnny Craighead, consider herself a climber.

She was a talented artist trained by her mother, an art teacher, with some of the country’s most spectacular backgrounds as her muse. But she didn’t consider herself an artist.

She was a model for famed Grand Teton photographer Harrison Crandall and appeared in war posters that went up around the country. But she probably wouldn’t have told you much about that.

To her children, Margaret “Cony” Smith Craighead was all of those things, but also a wife to one of the nation’s preeminent wildlife biologists and a mother who allowed her children to roam, explore and raise nearly any wild thing that ended up at their house– including mountain lion littermates, whoknows-how-many owls and one sparrow hawk that had a tendency to poop down the back of her curtains.

“Margaret simply loved being out-ofdoors, living rough, admiring the flowers and loving the wildlife,” Johnny said. “I think that is the reward she sought.”

COURTESY

rrington, Nevada, the only child of a father who taught science and mother who taught art. They moved to Utah soon after, and her father took the job of summer park ranger in Yellowstone National Park then later in Grand Teton. The family lived in canvas wall tents and she befriended some of the most famous climbers of that generation from Paul Petzoldt and Glenn Exum to Fred and Irene Ayres.

Those summers fostered a love of climbing, geology and the natural world that shaped Margaret’s life, Johnny said. She went on to earn a degree in geology, but World War II hit as she graduated, so she joined the war e ort, working at Hill Air Force base.

“She always maintained an interest in geology,” Johnny said. “In fact, cleaning up the house, she had every one of John McPhee’s books. She quietly kept all that interest. Of course she brought it to us kids by just being able to rock hound.”

She and John Craighead, that twin brother with the falcons in his backseat, kept in touch by lengthy correspondence before and during the war. They married and she, her sister-in-law and a friend lived alone running the Moose post o ce while their husbands finished their time in service. After the war, she and John built a log cabin in the shadow of the Tetons. That cabin became the family’s home base for decades, even after a move to Missoula, Montana, for John to teach at the university.

“I think the whole family always considered Jackson Hole home,” said her son Derek Craighead, founder of Kelly-based wildlife research institute Craighead Beringia South. “Even if it was a place we only got to a few times a year or for holidays. It was like going back home.”

· · ·

The family traveled back to Yellowstone and Wyoming nearly every summer. Margaret became a mother of not only Johnny, Derek and Karen Haynam, but also became “Mother Margaret” to every graduate student that worked with her husband.

In their house in Missoula, their cabin in Wyoming and their research station in Yellowstone where John and Frank studied grizzly bears, she fostered a love of nature in her children.

That is perhaps Margaret’s biggest contribution to wildlife and conservation. She carried the name Craighead – one synonymous with conservation in the West. She helped her husband and brother-in-law complete a field guide to Rocky Mountain wildflowers and supported him in all of his conservation achievements. But Margaret, who died in 2016 at the age of 96, largely made a di erence in her own ways.

“She encouraged us all to do artwork and get outdoors and hike and climb. She joined us on most of those adventures that she could whether rafting down the Middle Fork of the Salmon River or climbing in the Tetons,” Derek said. “She traveled with dad on his trips to Tibet and Russia and Egypt and she was always game to get on the camel or elephant and go for a ride.”

And then there was the wildlife in the houses and yard – the mountain lions, the Andean condor, the Steller’s jay and the owls. It was 50 years ago, a time when people dropped o wounded or orphaned animals with the local biologist.

“There was one story about packing up the kids at the end of school to go to the place in Jackson, and mom packed up the three kids, two Canada geese, a red fox and a prairie falcon,” Johnny said. “They’d all go in the car, and she’d jump in with them. All that stu was so natural, those were just the things we did.”