8 minute read

NEW MEDIA Meriem Bennani By: Emma Warburton

from Tribe 09

Meriem Bennani: Engineering Environments Discussions on immersive video installations

Emma Rae Warburton: How do you describe yourself as an artist? Meriem Bennani: I make video installations, but I don’t usually define myself. In the past couple of years, I’ve focused on a practice that starts with a documentary—like interest in a subject or person. And then I film the subject or people in question. Which then turns into a video of around 30 minutes. That’s been kind of a consistent pattern. But the video is not documentary; the second I start editing it, it becomes something else. And then it’s usually presented in a multi-channel and multi-screen installation.

Advertisement

EW: If the starting point is a subject or a person, what are you trying to arrive at? It there a common goal for your videos? MB: I’m really not goal oriented. I start intuitively, being attracted to someone or something that I come in contact with. Then I spontaneously film that person or thing. Through editing, I then come closer to understanding what it is about the person or thing that interests me. Usually, my work arrives at questions rather than conclusions and is about universal concepts.

EW: What is the role of photography in your work? MB: I take photos every day. I take a lot of photos. But only with my phone. So, I don’t really think about the medium.

EW: Where did your interest in video as a medium begin? MB: When learning how to do special effects for different production companies, I started experimenting with videos I would casually take on my phone, or videos from the internet on current events or famous music videos. As I played these videos, I would manipulate them. I then realised that they had power. Video is very powerful, and when you modify a famous video, the viewer questions what it is, which isn’t real anymore. I then realised the potential of storytelling with video, and decided to explore that. Before that I mostly worked in drawing and animation.

EW: Humour and comedy are integral to your practice. Can you talk about the importance of humour in your videos? MB: The humour is mostly intentional, but sometimes it’s not. It’s just how I naturally approach subjects. I think we all have a default mode of expression. If a subject interests me, I naturally approach it with humour It’s also a way of warming up to more serious subjects in my work. The way the audience interacts with humour mirrors my own interests in humour. This makes the work more accessible to people, as well as for me. I am very serious about the subjects that I approach. Although there is humour, I’m not interested in being sarcastic or ironic. I try to have a very full-hearted approach to things. I don’t use humour to create distance. I use it to be playful. My work is pretty optimistic and positive, which also is not planned.

EW: Where do you predominantly live right now? Does your location affect your creativity including your resulting work?

Video is very powerful, and when you modify a famous video, or when you modify a video and the viewer questions what is and isn’t real anymore, it has a lot of potential

MB: I’ve been living in New York for ten years. I do travel a lot and spend a lot of time in Morocco. It’s a luxury, but if you can have access to two centres instead of one, I think that’s very helpful. Wherever you stay for a long time ends up feeling like a centre which I think is very dangerous. When I spend too much time in New York, it is harder to get out of the bubble of being there, which is why I love going back and forth.

I think my work is very much about of someone that belongs to a diaspora - someone who misses where they’re from. But I also grew up in Morocco. I wasn’t born away. So my work moves between this feeling of being away from where I’m from, but also as being made from the inside, from within Morocco. I am very interested in the idea of having two gazes at once as well as the space in between them.

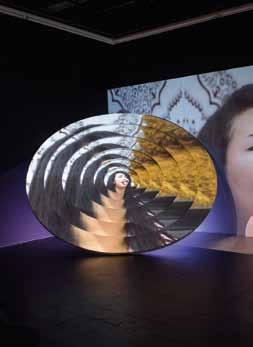

Image courtesy of the artist and BIM 2018. Photo by Mathilda Olmi.

EW: What is the role of the internet and technology in your work, conceptually and practically? MB: Those elements are often talked about, but I don’t think they’re important at all actually. I think they’re a part of my life the way they’re a part of my mother’s life. Maybe I’m from a younger generation, so it makes more of an appearance in my work than it does for someone from an earlier generation. And it makes less of an appearance in my work than for someone ten years younger than me. But I’m not interested in situating them as central subjects. They’re just mediums. The internet and technology are there, and they give me access to different information and images from all over the world. But I’m not comfortable describing my work as something that is of the internet, or post internet. I find those terms to be very limiting because they just describe the reality we are living in today. EW: This brings me to my next question, how do you feel about technology and its current relationship to art and creativity in general? MB: It’s really hard to respond in general, because there are so many types of technologies, and there are so many artists that use technologies for different reasons. I’m interested in technology just being there to serve an idea. So the idea of technology as a tool. But for one to simply place their work in the context of new media and technology, I find that very boring. For example. when VR is used in a way that doesn’t justify its presence, it just sort of takes over because people are still very impressed by VR, leaving no room for the work. And I think that sometimes when artists use computers or technological devices in their work, they’re put into a category. But it’s only a medium.

EW: Would you describe your work as political? MB: Everything is political. It’s impossible for anyone to not be political. My presence in the world is inherently political. I don’t make work always with the intent of being political, or analytical in a political way, or having it be political commentary. But I do make work knowing that by default, whatever I’m talking about will have political content within it, and wherever I show it will determine how that political content resonates. So it’s not that I decide to make political work, it’s more that once I’m interested in something, I have to sit down and determine the political charge of it, and really think about it.

EW: What are some of the core concepts that you engage with in your videos? Are there any repeated motifs?

Clockwise: Stills From Video, Still from Meriem

Bennani, Ghariba (2017)

Installation view, Ghariba, Art Dubai (2017)

Photo by Photo Solutions.

MB: I film a lot of women in my family. I’m also very much attracted to music and dance. But those themes, without the specifics, are very general.

EW: Do you know why you revisit the women in your family as subjects in your work? MB: Well, I sometimes ask people to role play. And I happen to have a mother, aunt and some of my mother’s cousins that are really great at improv. They are identities themselves but with a bit role to play, and they do it really beautifully. I work with female characters that already as a child felt like characters - their personalities and their presence was always so fabulous and political that they were already characters.

EW: Is your own mother a real force and strong personality? MB: Yes, I would say so. EW: Right now, what’s the most essential part of your process? MB: There are multiple important turning points. The first one is the research phase, when I come up with a new idea. Then, during shooting, so many things start happening. A very crucial moment is the editing, because I don’t make the story when I shoot. So the story comes together when I edit. And then the planning of the installation elements becomes very important .

EW: From the initial research phase, to the final stage when an idea is materialized in an installation, is there a sense of great departure? MB: Absolutely. Completely. I once found a musician, or performer I wanted to work with. Initially I was interested in a musical genre. She kind of flaked on me. And I had made a whole project around her. So I had to work with two other women, and I had no idea what to expect. I had four days with them. And the footage I have is nothing that I could have planned. When it comes to the installation, I have more control since it starts with 3D shapes that I draw on my computer, that a fabricator then tries to replicate. If I wasn’t working with video and installation the way that I am now, I think I would write fiction films. I’m interested in the process of projecting an idea onto a subject, and then having it surprise me. The way a person might talk about something, I couldn’t even write that. I couldn’t even make it up, because it comes from a totally different person with a different life. And through that exchange I am taken out of the things I know. And it’s always different. If it wasn’t different I think it would be boring, or it would mean that I wasn’t open to people.

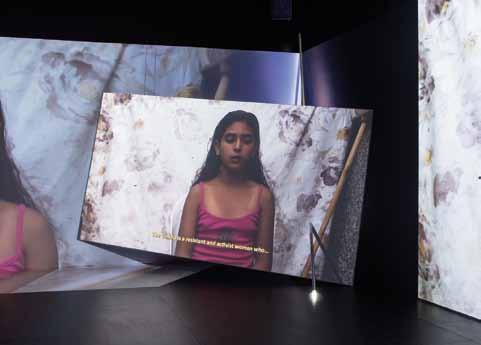

Installation view, Siham & Hafida at The Kitchen (2017) Photo by Jason Mandella