10 minute read

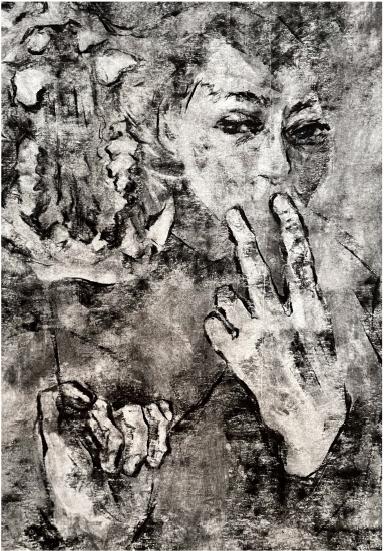

NO MANS LAND BY GONYA LUATE

South Sudan is situated in East Africa. The country borders the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, Uganda, and Ethiopia.

South Sudan is supposed to be my home.

The land – an accumulation of dust, grass, and dirt – cultivated by my people.

An ancestral lineage that trails through history; a singular line. The soil hardened by the compacted dirt and the manure scattered under the tall wheat.

The children play alongside the livestock, the sun piercing through the sky. As the children shuffle in and out of the tall grass, speeding up and down the paddock and racing competitively alongside the goats; the women go to the market.

Sun down approached the city – a shadow of the city of Juba trails behind the silhouettes of the women. Their endless chatter follows them through the afternoon. Sound waves bouncing off the tukul huts and echoing into the ceaseless chasm - the humid sky and incubated warmth. The following conversations take place:

“Wallah zol de mah be agdel amalu aya hajah, malesh!”

Wallah! That man can’t do anything, sorry.

“De zol mujunun, o be wonoosu kalamfarik.”

That’s a stubborn man, he speaks nonsense.

“Ah Maloo? Itacum be attiku kooliyom!”

Ah what’s wrong? You guys are always laughing!

Broken languages mended together on the dust swept streets of Juba, home.

My people are strong – it runs through ancestral lineage. The Mundari clan are warriors.

My Father told me that my name reflects my life – my history and my culture.

My name is Estell [Gonya Luate] Luate.

A name birthed out of refuge and unfamiliarity – my name reflects my circumstance, my being, my presence, and my absence.

I was named after an ancestral figure, passed through from 3-4

She was shot in the leg – a crutch nuzzled under her left armpit, safinja ¹ collecting dust at her feet, a broadened smile revealing deep wells where teeth should be – I only met Gonya once. Not the original Gonya, but a successor. The original Gonya is a predecessor – I am a successor. My father says that his grandfather had not even seen Gonya. Gonya –a character legacy – my name. At times, I wish to reach deep into my myself into the abyss of my endless heritage and far into the ancestral

To know, feel and understand what being a Gonya entails.

My identity stands before me with a gaping hole in the middle. The shape is odd, I realise that I have no pieces that resemble its shape. The shape is obscure – maybe if I wrapped my arms around my body and stretched certain ligaments in my body, maybe I would be the missing

Names are valued in my culture. They tell a narrative – an extensive, fulfilled, and detailed representation of your history.

My father’s first name. My last name.

Luate defines the circumstances surrounding the birth of my father; the boy amongst many girls.

My name is Estell [Gonya Luate] Luate, it reflects the diversified nature of my birth and my family.

The name Estell was given to me upon our endeavour to Australia. A journey that lead to unfamiliarity and struggle. Often the struggle is associated with Africa, its depleting wealth and poverty-stricken countries; but for us it began in Australia.

Estell supported my family and our attempt to assimilate into Australian culture, her final gift to our family was her name; to be given to their new born baby.

They called me the Australian.

My parents told me that if anything happened, if they were ever told to return to South Sudan that I would be their hope. They’d say, “No our daughter, she is Australian, she has a birth certificate. You cannot deport her - you cannot deport us; we need to support her”.

My only understanding of life has been built in Australia. But, I am yet to form this prideful response to national identity and Australian culture.

Living in Australia as a South Sudanese migrant is far from simple. There is an intercultural shift that takes place – the difficult nature of identifying with one culture yet trying to assimilate into another. This balance that must be established when attempting to fully engage yourself in Australian culture, yet not lose sight of your roots.

The island state of Tasmania is located southwards of mainland Australia, the land itself is rich in agriculture and serene destinations.

She walks – she strolls down the streets of Evandale, her heartbeat in time with her steps, in time with each breath, in time with the pulse of the sun streaming on the road by her side. Entering the gates that lead way towards the Evandale marketplace, her senses are greeted with an array of bitter coffee – the confined heat seeping from cardboard cups, to the fresh produce scented with lemon and grass. Approaching a stall, she is stopped by a middle-aged lady, with a coffee in hand. The lady settles her eyes on her face.

A soft gaze accompanied with metallic eyes.

“Hello, how are you?”, she addresses the girl – eager for a response. Eager for the conversational aspect of her words to dissipate, that she may address her only concern.

“I’m good, thank you. How are you?” Reciprocating a kind manner, the girl hinted a smile on her bottom lip.

“I am great, thank you for asking! And where are you from?”

The question caused great disturbance to the girl, internally she arranged her thoughts and ordered them carefully.

I am fully Australian. I am also fully South Sudanese. Neither will forfeit at the expense of the other.

I must consider the interests of the Sudanese community.

I must consider the interests of the Australian community.

Within my own intercultural lifestyle – I have learnt to live in No Man’s Land, the strip of land that distinctly divides these two cultures.

Alienated as the opposing sides fight. Alienated as the few other’s in No Man’s Land flee to one side, only to be held hostage. We do not belong on one side or the other, we do not belong in No Man’s Land.

We should not be in war.

My name is Estell [Gonya Luate] Luate.

I am an Australian South-Sudanese.

When I reflect on what the role of the Arts is in the Trinity community, its purpose to me is instantly clear – it is about bringing energy and vibrancy to our college lives. In my experience, having a passion for the Arts and committing to creating an artistic community that can flourish, builds the foundation for a developed sense of identity, creativity, and belonging. I love all the ‘hidden skills’ that we build through engaging in a wide variety of artistic endeavours. Confidence and greater self esteem, a sense of community and friendship, collaborative skills and trust in others – all of which really underpin our motivations for being in a College community to begin with!

I am so excited to continue to build off the fabulous efforts of the previous TCAC and Arts Representative as we continue to navigate how best to rebuild our appreciation of the Arts in a post-covid environment. I am envisaging that to do this, my work is going to involve publicising more arts events and activities leading to greater involvement in artistic facets of College life, using the JCR and other platforms to promote local performers and artistic success in our community, and developing our understanding and appreciation of art in a broader context, through connecting with alumni, collaborating with the TCAC and intercollegiate community. I hope in this way to broaden our concept of ‘art’ in the community – journalism, theatresports, poetry, photography, language, writing, debating and more!

Having a background in mainly the performing arts, I am eager to have the opportunity to promote and organise iconic arts events in our social calendar, such as the Musical, Play and Arts Gala. But perhaps most importantly, I am excited at the opportunity we now have to work on how we use art to our advantage to promote inclusivity in the College community.

The Arts at Trinity is slowly coming back to life, and I am looking forward to being proactive in making changes that our students most want to see in the community and arts space. I’m excited to expand the College’s understanding of what the Arts can provide to us on an individual level, and also to strengthen bonds with each other.

Above all, I’m excited at the opportunity to listen to the voices of the community as we expand.

References

Rahim Bahloui, The Consequences of Hypocrisy: Understanding Discrimination against Middle Eastern People in a Western Context https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/press-release/2021/03/eu-anniversary-of-turkey-deal offers-warning-against-further-dangerous-migration-deals/ https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2022/01/libya-eu-conditions-remain-hellish-as-eu marks-5-years-of-cooperation-agreements/

Amnesty International. (2021, March 12). EU: Anniversary of Turkey deal offers warning against further dangerous migration deals.

Amnesty International. (2022, January 31). Libya/EU: Conditions remain ‘hellish’ as EU marks 5 years of cooperation agreements.

UNHCR. (2022, September 13). Refugees from Ukraine recorded across Europe. https://data. unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine

The White House. (2003, March 2022). President Discusses Beginning of Operation Iraqi Freedom. https://georgewbush whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2003/03/20030322.html

Iraq Body Count. (2022, August 30). The public record of violent deaths following the 2003 invasion of Iraq. https://www.iraqbodycount.org

Watson Institute, Brown University. (2021, August). Costs of War: Iraqi Refugees. https:// watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/costs/human/refugees/iraqi https://scholarship.depauw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1129&context=studentresearch

Woods, G. (2019). Adventure, Intrigue, and Terror: Arabs and the Middle East in Hollywood Film Music. [Honor Thesis, DePauw University].

Gonya Luate, the Vilification of South Sudanese Youth

ABC News. (2020). Meet three south sudanese refugees making their mark in australia. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-07-12/meet-south-sudanese-refugees-making-their-mark/12434498

ABC News. (2018). The Daily Mail and Gang Misappropriation. Retrieved from https://www. abc.net.au/mediawatch/episodes/the-daily-mail-and-gang-misappropriation/9972808

ABC Media Watch

Abur, W. (2018). Systematic Vilification and Racism Are Affecting on the South Sudanese Community in Australia. International Journal of Scientific Research. Retrieved from file:///C:/Users/ gelua/Downloads/SystemVilificationandRaacismareaffecttingontheSouthSudanesCommunityinAustralia.pdf

Budarick, J. (2019). Why the media are to blame for racialising melbourne’s ‘african gang’ problem. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/why-the-media-are-toblame-for-racialising-melbournes-african-gang-problem-100761

Burin, M. (2018). People Think All African Kids Are Bad. ABC News. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-08-08/melbourne-sudanese-families-overcoming-gangstereotype/10016858?nw=0

Coventry, G., Dawes, G., Moston, S., & Palmers, D. (2014). Sudanese Australians and Crime: Police and Community Perspectives. Australian Institute of Criminology. Retrieved from https:// www.aic.gov.au/publications/tandi/tandi477

Davey, M. (2016). Melbourne Street Brawl Blamed on Apex Gang After Moomba Festival. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2016/ma r/14/ melbourne-street-brawl-blamed-on-apex-gang-af ter-moomba-festival

Henriques-Gomes, L. (2018). South Sudanese-Australians Report Racial Abuse Intensified After ‘African Gangs’ Claims. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/ nov/04/south-sudanese-australians-report-abuse-intensified-after-african-gangs-claims Jimma, N. (2020). South Sudanese refugees on the Challenges of Making a New Life in Australia. ABC Radio Melbourne. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-07-12/meet-southsudanese-refugees-making-their-mark/12434498

Media Highlights. (2018). Refugee Gang Crisis in Melbourne Australia [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tseUeTGrXsU

O’Connor, R. (2017). Section Boyz: Daily Mail Article Used Image of South London Grime Crew for Story About Australian Gang Violence. Independent UK. [Photograph]. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/music/news/section-boyz-daily-mail-articlephoto-australia-apex-gang-violence-a7556476.html

The Project (2018). Why Pollies Want You to Fear African Gangs. Network Ten. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://10play.com.au/theproject/recap/2020/why-pollies-want-you-to-fearafrican-gangs/tpv190915raskv

Wahlquist, C. (2018). ‘We’re not a gang’: the unfair stereotyping of African Australians. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2018/jan/06/were-not-agang-the-pain-of-being-african-australian

Abur, W. (2018). Systematic Vilification and Racism Are Affecting on the South Sudanese Community in Australia. International Journal of Scientific Research. Retrieved from file:///C:/Users/ gelua/Downloads/SystemVilificationandRaacismareaffecttingontheSouthSudanesCommunityinAustralia.pdf

Urszula Nowak, The Children Overboard Case - Gender, Race and Class ABC. (2002). Children Overboard—4 Corners. In Four Corners.

Anderson, Z. (2012). Borders, Babies, and “Good Refugees”: Australian Representations of “Illegal” Immigration, 1979. Journal of Australian Studies, 36(4), 499–514. MLA International Bibliography.

Ang, S., & Colic-Peisker, V. (2022). Sinophobia in the Asian century: Race, nation and Othering in Australia and Singapore. 45(4), 419–514. British Library Document Supply Centre Inside Serials & Conference Proceedings.

Anthony Moran. (2005). White Australia, settler nationalism and Aboriginal assimilation. Australian Journal of Politics and History, 51(2), 168. Multicultural Australia and Immigration Studies.

BBC. (2022, April 23). How many Ukrainians have fled their homes and where have they gone? BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-60555472

Commonwealth Parliament; address=Parliament House, C. (2002). Chapter 3 - The Children Overboard; Incident: Events and Initial Report (Australia) [Text]. https://www.aph.gov.au/ Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Former_Committees/maritimeincident/report/c03

Gans, Herbert J. (n.d.). Chapter 10: Race as Class. In Race, Class and Gender: An Anthology: Vol. 9th Edition. Cengage Learning.

Karvelas, Patricia. (2002, August 24). Accused detainees demand apology—CHILDREN OVERBOARD VERDICT—Record details—EBSCO. https://discovery.ebsco.com/c/xppotz/ details/ix67hh32k5?limiters=FT1%3AY&q=%22children%20overboard%22%20AND%20 mother%2A%20AND%20australia%2A

Lasky, J. (2020). Stolen Generation. In Salem Press Encyclopedia. Salem Press; Research Starters. Macken-Horarik, M. (2003). Working the borders in racist discourse: The challenge of the ‘Children Overboard Affair’ in news media texts. Social Semiotics, 13(3), 283–303. https://doi. org/10.1080/1035033032000167024

Marx, Karl & Engels, Frederich. (1848). The Communist Manifesto. Penguin Classics 2010.

O’Donnell, M., Taplin, S., Marriott, R., Lima, F., & Stanley, F. J. (2019). Infant removals: The need to address the over-representation of Aboriginal infants and community concerns of another “stolen generation.” 90, 88–98. British Library Document Supply Centre Inside Serials & Conference Proceedings.

Ramsay, G. (2016). Black Mothers, Bad Mothers: African Refugee Women and the Governing of ‘Good’ Citizens Through the Australian Child Welfare System. Australian Feminist Studies, 31(89), 319–335. https://doi.org/10.1080/08164649.2016.1254021

Said, Edward. (1979). Orientalism. Penguin Classics.

Tondo, L. (2022, March 4). Embraced or pushed back: On the Polish border, sadly, not all refugees are welcome. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/ commentisfree/2022/mar/04/embraced-or-pushed-back-on-the-polish-border-sadly-not-allrefugees-are-welcome

UNHCR. (n.d.-a). Asylum-Seekers. UNHCR. Retrieved April 26, 2022, from https://www. unhcr.org/asylum-seekers.html

UNHCR. (n.d.-b). What is a refugee? UNHCR. Retrieved April 26, 2022, from https://www. unhcr.org/what-is-a-refugee.html

Zinn, M. B., Hondagneu-Sotelo, P., & Messner, M. (2016). Sex and Gender through the Prism of Difference. 9.

Freya Giles, The Role of Visual Images In The Construction and Negotiation of Identity in The Present

Bullingham, L., & Vasconcelos, A. C. (2013). ‘The Presentation of Self in the Online World’: Goffman and the Study of Online Identities. Journal of Information Science, 39(1), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551512470051

Cantrell, S. J., Winters, R. M., Kaini, P., & Walker, B. N. (2022). Sonification of Emotion in

Social Media: Affect and Accessibility in Facebook Reactions. Proceedings of the ACM on HumanComputer Interaction, 6(CSCW1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1145/3512966

Frosh, P. (2015). The Gestural Image: The Selfie, Photography Theory, and Kinesthetic Sociability . International Journal of Communication, 1607–1628.

Goffman, E. (1956). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Doubleday.

Hilsen, A. I., & Helvik, T. (2012). The Construction of Self in Social Medias, such as Facebook. AI & SOCIETY, 29(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-012-0426-y https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878x1214500112

Horst, H., & Miller, D. (2012). Normativity and Materiality: A View from Digital anthropology. Media International Australia, 145(1), 103–111.

Leary, M. R. (2019). Self-Presentation: Impression Management and Interpersonal Behavior. Routledge.

Raymond, C. (2021). Dreaming the Self: Selfie Practice, Temporality, and Artificial Intelligence. The Selfie, Temporality, and Contemporary Photography, 1–19. https://doi. org/10.4324/9780429319044-1 https://doi.org/10.1080/17540763.2016.1258657

Serafinelli, E. (2017). Analysis of Photo Sharing and Visual Social Relationships: Instagram as a Case Study. Photographies, 10(1), 91–111.

Subrahmanyam, K., & Šmahel, D. (2010). Constructing Identity Online: Identity Exploration and Self-Presentation. Digital Youth, 59–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419- 6278-2_4 van Dijck, J. (2008). Digital Photography: Communication, Identity, Memory. Visual Communication, 7(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/147035720708

Urszula Nowak, Two Men Dancing and Depictions of Male Homosexuality Adler, Amy. “The Shifting Law of Sexual Speech: Rethinking Robert Mapplethorpe.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 2020 (January 1, 2020): 1–44.

Arn, Jackson. “Are Robert Mapplethorpe’s Photographs Still Controversial?” Artsy, January 14, 2019. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-mapplethorpes-photographs-remainsubversive-shock-value.

Carolan, Nicholas. “The Perfect Timing of Robert Mapplethorpe’s ‘Perfect Medium.’” Grazia (blog), 2017. https://graziamagazine.com/articles/the-body-electric-robert-mapplethorpesperfect-medium/.

“Chiaroscuro.” In Salem Press Encyclopedia. Salem Press, September 30, 2021. Research Starters. Northcross, Wayne. “Mapplethorpe as Demon Seducer.” The Gay & Lesbian Review 7, no. 1 (January 1, 2000)

Image references for this essay

Mapplethorpe, Robert. Two Men Dancing. printed 1990 1984. Gelatin Silver Print, 48.5 x 38.6cm. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. https://www.artsy.net/artwork/robert-mapplethorpetwo-men-dancing.

Canova, Antonio. Wrestlers. 1775. Painted Terracotta, 39.5 x 34 x 20cm. Galleria dell’Accademia.