19 minute read

SPANISH FLU IN ABERDEEN

he first reported case of what became known as Spanish Flu was in a Kansas Army camp in March 1918. There were also outbreaks on the East Coast, tending to occur where soldiers prepared for World War I. When they went overseas, the virus went with them. Many soldiers and civilians on both sides of the fight became sick, and many died. In the United States, meanwhile, the spring epidemic faded away.

Advertisement

Miss Aberdeen Faith Nell posed for our vintage recreation of an Aberdeen scene during the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic. Costuming supplied by Aberdeen Community Theatre and Paige Waith. In the background is an early 1900s image of the Northwestern National Bank building, which is now the Dacotah Prairie Museum (who also supplied the photo).

Author’s note: A few issues ago, as we entered the 2020s, my article about 1920s Aberdeen appeared here. In discussing antecedents of the decade, I noted World War I and other events, but not the 1918 influenza pandemic. In fact, while about 900 Brown County men were called up for the war, only 49 died. Only is an inadequate word choice, but as will be clear, flu was a greater enemy (many of those soldiers died of flu). Yet despite its magnitude, I overlooked it, and I’m not alone. COVID has made many look back. In my earlier story, I smugly proposed the cliché that history may not repeat itself, but sometimes it rhymes. And sometimes it repeats.

Historians believe the virus came back from Europe by ship, probably with returning American soldiers, since the camps again became hot spots. New recruits continued to be sent to Army camps around the country, and in those close quarters, the influenza spread, this time with a vengeance. A much harsher form of the flu now accompanied troops when they moved between camps. By early October, more than 100,000 soldiers were sick in camps across the country. The men didn’t stay in the camps, and neither did the virus.

At the time nobody knew a virus caused influenza. Science blamed a bacterium, a misunderstanding that stymied vaccine research. Another 15 years passed before the flu virus was discovered.

HUB CITY In an early October 1918 newspaper, Dr. Louis Holtz, Aberdeen city health officer, anticipated the disease’s arrival. He understood, the paper said, “that Aberdeen is quite a railroad center.” When the flu came, it probably came by train.

An October 5, 1918, newspaper reported the first three flu cases in Aberdeen with others “under suspicion,” but Dr. Holtz had “no fear of this disease spreading to any extent.” Even though the next day’s paper reported more cases, health officials told the public not to be alarmed because “we have the situation pretty well in hand.” It was common nationwide for officials and newspapers to downplay the disease. Within days, State Director of Health

Dr. Park Jenkins of Waubay reported 109 cases in Brown County.

Jenkins ordered all doctors to report cases daily to the state office or risk losing their license. Soon, local cases numbered 300 and then 600. (Unfortunately, newspapers were not always clear whether the numbers reported were for Aberdeen or Brown County or whether they were new cases or cumulative cases. Archives did not preserve case counts.) Perhaps less sanguine than before, Dr. Holtz believed fewer than half of all cases were being reported and found it “deplorable” that doctors were failing to report them.

Holtz’s scolding might have been unfair because the doctors were busy. In addition to tending to local patients, Aberdeen physicians regularly drove to other county towns, and caring might have outweighed reporting. Mrs. Wilfred Bassett, quoted in a Presentation Sisters history, noted that doctors “were in their cars day and night, even slept in their cars at that time.”

And some died. Hecla’s only doctor, Charles Holmes, died of influenza in mid-October. The 45-year-old left behind a wife and twoyear-old. Three days later, his home became a temporary hospital.

VICTIMS During the epidemic, one paper reported, "Thus far the influenza in the city has not been of the virulent type. It is similar to the grip which seized

SPANISH FLU?

What’s with the name of the disease? It’s a politically incorrect name but, also, geographically incorrect. Spain is one of the places researchers are sure it didn’t originate. Because Spain was neutral in World War I, its newspapers weren’t censored, so they reported on flu in the country. This led other censored European papers to write about their neighbor’s plight, blaming the “Spanish Flu,” and the name caught on. Except in Spain, where they called it the “Naples Soldier,” perhaps because they blamed Italians for bringing it to the country, but more likely it came from a song of that name from an operetta. One said the flu was as catchy as the song. The other name was more contagious.

The geographic origin of the H1N1 virus strain that produced the pandemic remains uncertain. The generally acknowledged first patient diagnosed with the disease was a cook in a Kansas military camp who became ill on March 4, 1918. However, it’s not certain he really was the first patient. In the preceding two months, a brief outbreak of flu had been in rural Kansas not far from the camp. There were also other outbreaks of diseases in other parts of the country and the world that may or may not have been the same disease. Some researchers have suggested Europe and Asia as points of origin as well, but the search is complicated by the challenge of tracing the lineage of a virus more than a century old — one that might have passed among humans, birds, pigs and horses before returning to humans in 1918.

the nation twenty years ago and while there are several cases in town most of them are not yet so bad" (“grip” and “grippe” were synonyms for influenza). It’s not clear exactly how virulent the disease in Aberdeen was because little was reported about victims’ actual experience. Across the pandemic, most recovered after typical symptoms — fever, cough, and sore throat — but some suffered a brutal disease that so ravaged the lungs that victims bled from nose, mouth, and eyes. A reduction in oxygenation turned skin blue. Some people died within hours of showing symptoms.

John M. Barry, in The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History (2004), suggests flu tended to make its earliest victims sicker than those infected later in a local epidemic. Similarly, the areas hit earliest were struck harder than later ones. The East Coast and the South seemed harder hit than the West Coast, which was hit harder than the interior. Barry also suggests it’s possible that during the pandemic the virus mutated to a less virulent form.

Within a week of the first cases, Aberdeen suffered its first flu death, but the papers didn’t identify the victim. Whoever died first, many followed.

A snapshot of obituaries points to an unusual aspect of the pandemic: Clarence Johnson, 19, whose brother and sister were also ill; Anna McGlauflin, 20, left behind a husband in the army

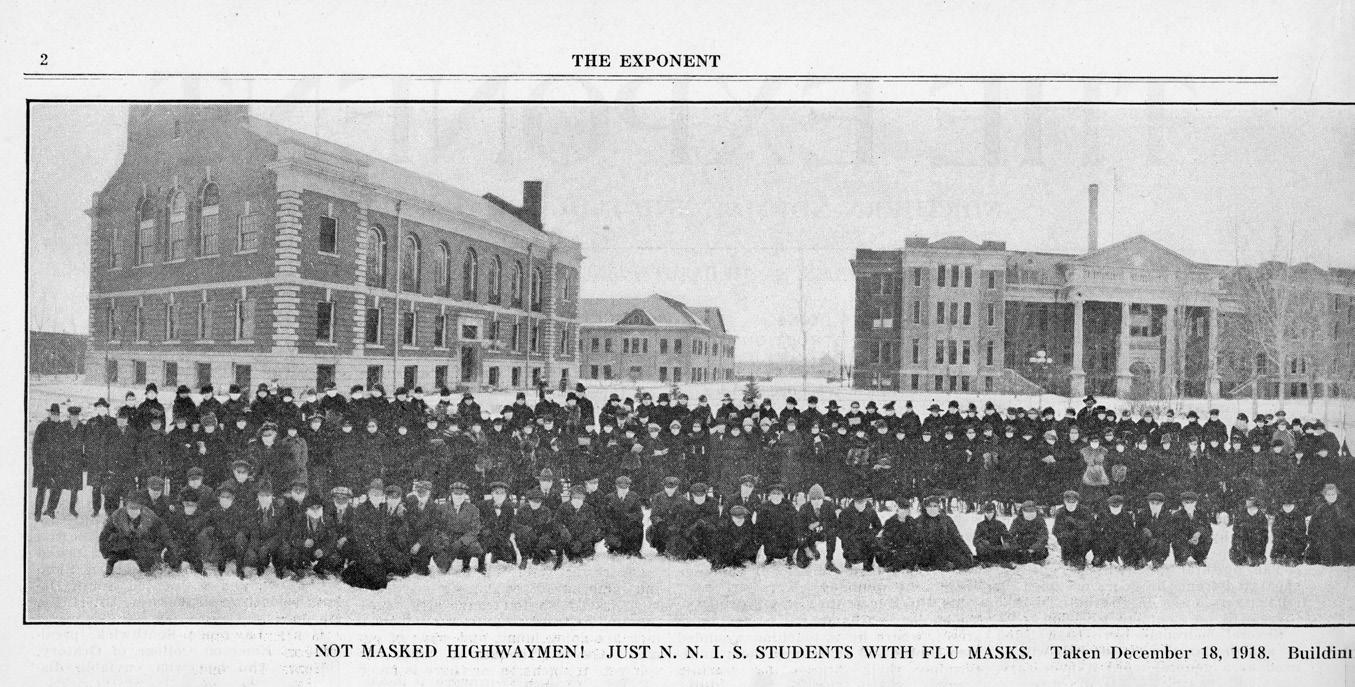

From Northern’s The Exponent archives: in 1918, students gathered on Northern’s snow covered campus in face masks. It was the height of the Spanish Flu pandemic. Graham Hall was turned into a makeshift hospital to help shoulder the influx of infected patients. Image supplied by Stephanie Cossette, Archivist, Beulah Williams Library, Northern State University.

and a six-month-old as well as eight sick family members; Ashley Brundage died on her 21st birthday and had a brother and sister seriously ill; Grace Johannsen, 23, was to be married within a month to Mark Anthony, who died within 12 hours of his fiancé — they would instead have a joint funeral. This group exemplifies the virus’ outsized impact on people in the prime of life. Almost half of all Spanish Flu victims were 20 to 40 years old. Because of this, average life expectancy in the United States declined by almost 12 years.

CARING Caring for loved ones was dangerous. In Rapid City, Hazel Mee, daughter of Aberdeen’s wellknown Easton family, cared for her husband and 13-month-old daughter when they couldn’t find nursing care. When she became sick, her parents found a nurse, who also became sick, and Hazel died soon after. In another instance, Elsie MannCase became ill while caring for her husband and son who were too sick to come to her deathbed.

Other obituaries shed light on the problems above: Barbara Field, 26, died while her husband, a doctor, was serving in France. Red Cross nurse and 1918 St. Luke’s nurse graduate Naomi Templin died in Camp Grant in Illinois. Across the country, the military had taken many doctors and nurses. Health care workers were stretched thin. St. Luke’s Hospital, which had opened in 1901 with 15 beds, was quickly “overflowing with grippe cases.” Mrs. Bassett, quoted earlier, said, “They thought they would be able to open some of their rooms at the hospital, but there were so many that they couldn’t take care of one-third of the patients.” The hospital could accept no more flu patients, only pneumonia victims (pneumonia was the most common cause of flu death). As a response, officials set up temporary hospitals in Aberdeen and county towns, including in Northern’s Graham Hall, and St. Luke’s nurses took charge of them. A hospital history notes, “Mother Raphael and the late H.C. Jewett helped to set up and equip these emergency hospitals. Hundreds of patients were cared for by Sisters, senior nurses and lay helpers.” A Presentation Sister assisting St. Luke’s superintendent Sister Raphael, would later become Superior of the Presentation Convent. A history of the Presentation Sisters reported the Sisters, who operated and largely staffed St. Luke’s, “volunteered their services whenever needed, especially where an entire family was stricken.” Many local Sisters contracted influenza, but none died of it.

H.C. Jewett was chair of the Brown County Red Cross. Initially involved in the war effort, the

REMEMBERING FLU

Most of this article is based on newspaper accounts of the epidemic in Aberdeen as it was happening. Famously the “first draft of history,” journalism — in Aberdeen and most of America — seems not to have fed much history. There hasn’t been much writing on the pandemic, especially compared to other major historical events. Laura Spinney, author of Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World (2017), found that WorldCat, the large library catalogue database, lists approximately 80,000 books about World War I but only around 400 on the 1918 flu.

This isn’t a phenomenon of just academic research. More often than not, various local histories I checked, such as those of local churches (probably all of whom buried parishioners), said nothing about the 1918 flu. Brown County History, a book written in preparation for the 1981 centennial, includes information about the flu, but its index has 54 entries for World War I and nine on the 1918 epidemic.

Others have speculated on the reason for this general lack of memory about the pandemic. Spinney suggested, “Memory is an active process. Details have to be rehearsed to be retained. But who wants to rehearse the details of a pandemic? A war has a victor, and to him the spoils…But a pandemic has only vanquished.”

Red Cross was important in caring for influenza victims. Taking advantage of an overwhelming patriotic war spirit, the Brown County chapter called on the “practical patriotism” of Aberdeen women to help make 4,000 flu masks for army training camps. Jewett frequently toured the emergency hospitals, noting in mid-October, “Conditions in the county are pretty bad, and people cannot realize or appreciate what suffering is going on, until they make the rounds and see it.”

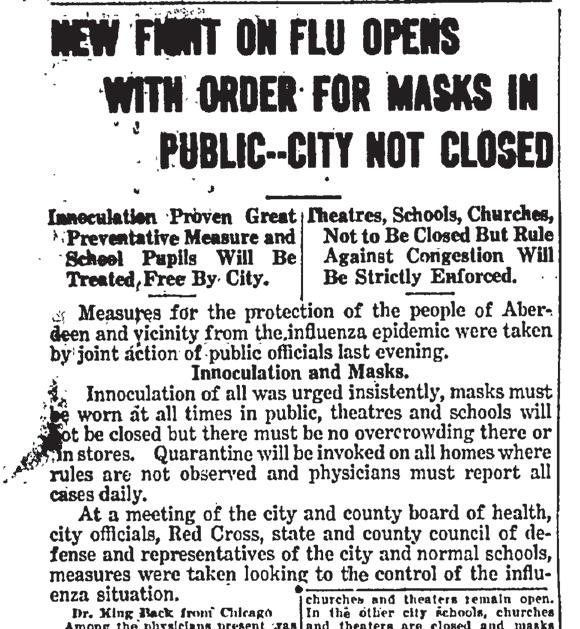

INTERVENTIONS The city attempted to mitigate disease spread. While minutes show the City Commission took no action regarding the flu, others did. On October 11, a week into the epidemic when Aberdeen had about 200 cases, Mayor A.N. Aldrich issued an order closing all churches, public and parochial schools, theaters, dance halls, and other public places. Northern Normal closed. High school football was upended. The local Republican Party cancelled campaign talks by Governor Peter Norbeck (who also contracted influenza).

Some public events still occurred. On November 5, the nation voted. South Dakota decided many state races as well as a constitutional amendment on women’s suffrage. In Brown County, about 4,000 men voted for the last time without women, who won the right to vote. Most Republicans won too.

The next week, a headline said, “Aberdeen Forgot the ‘Flu’ and Turned Out for a Spree!” On November 11, Germany accepted terms of surrender, ending conflict in World War I. That morning, the “banking girls” got permission to celebrate and started an impromptu parade down Main Street, collecting recruits from businesses until the celebration covered a dozen blocks. Then, the “big parade” started at three o’clock. Hundreds, probably thousands, celebrated downtown. Festivities lasted past midnight.

A week later, about five weeks after issuing it, the city lifted the closing order. “Aberdeen can go to show,” a headline exclaimed. Merchants were optimistic and relayed the reopening “by telegraph and telephone to virtually every section of the state, and many people who have feared to come will now take their long deferred trips to the metropolis.”

MASKING Despite the confidence of the reopening and headlines forever suggesting a declining epidemic, a mid-December story reported that the Commercial Club, which had earlier been designated headquarters for the local war effort, would become an emergency hospital “for the great number of cases in the city and county surrounding.” The story also noted, "Chairman H.C. Jewett of the Red Cross declared that the flu situation was worse now than at any time since the epidemic broke. It had receded but was now coming back worse than it was in the first instance." In mid-December, weekly case counts jumped to between 400 and 500.

On December 16, a month after the city reopened, the health board ordered compulsory wearing of masks in all public places. The health board’s Dr. Alway (filling in for Dr. Holtz, who had abruptly resigned in November) said the board aimed “to stop the epidemic in its present tracks, and the public will be a big factor in stopping it, if the public will adopt and rigidly live by the precautions set forth." Wishful thinking.

Patriotism was again a tool. One official felt that when people understood the “patriotic Americanism” in wearing a mask, they would do so because “all Americans are patriotic.” The Aberdeen Merchants Association pledged to enforce the mask order. At first, a paper reported, "Probably three-fourths of the people who were visible on the streets at noon today were wearing the mask…There are very few 'conscientious objectors.'"

But there were objectors. Dr. R.L. Murdy opposed the mask mandate as “hysteria.” While he agreed that those sick with flu should wear masks, he argued that for others masks were "incubators for germs." He further suggested that the 1918 epidemic was "nothing but another visit of similar epidemics which have visited the country three or four times each century." This flu was different, but that might have been hard to see from the inside.

Murdy’s view prevailed, however. A week after issuing the order, the health board lifted the mask-wearing requirement. Dr. Alway reported the health board, “in common with all well-informed persons,” believed in “the efficacy of the influenza masks” and asked the public to continue wearing them, “as a duty each one owes to himself as well as his neighbor." Alway also held mask critics "responsible for the disregard of the masking order, which disregard will undoubtedly be the cause of several deaths and hundreds of cases of disease."

Cases did continue to mount, with hundreds reported over the coming weeks. Brown County History (1980) noted, “Christmas day of 1918 was a black Christmas — more people died on that day than on any other.” Whether the increase was due to rejecting masks is unclear. It's readily acknowledged that masks in 1918 were often

of poor quality — frequently homemade from inadequate material — and often not worn. Relief from the disease may ultimately have come only because the virus mutated and weakened.

DENOUEMENT In mid-January 1919, a headline announced, “Influenza epidemic has run its course say city's doctors.” It wasn’t the first time such optimism appeared. Sounding the same confidence as after the city’s reopening, the story added, "Business, so seriously hampered by the outbreak of the epidemic and the disproportionate alarm which the disease caused, is now regaining its normal course and within a few days will be entirely recovered from the setback." But now the epidemic really was receding. Although the flu hung around until summer, by the end of January, the number of cases reported dropped to a relative handful per week, often zero. While the third wave was severe in many parts of the country, Aberdeen’s experience was nothing like the fall had been, and life became more normal.

Pursuing the “disproportionate alarm” comment above, one might wonder what circumstances would have made the response seem proportionate to the writer. Globally, the Spanish flu killed between 50 and 100 million people, perhaps 6% of the world’s population, in a handful of months — almost as many as all combat and civilian deaths in all 20th century wars. An estimated one-fifth of the world’s population became sick. The toll in the United States was lower proportionately but still immense: 675,000 deaths — about 0.6% of the population — more than total U.S. deaths in all 20th century wars. More World War I U.S. servicemen died from influenza than from combat, and nearly half died in the States, not in the theater of war. Economically, the U.S. as a whole recovered relatively quickly. It helped that the war created huge demand.

In South Dakota, influenza claimed about 0.3% of the population. Year-to-year statistics help tell the tale.

Influenza Deaths

South Dakota

54 1,847

Brown County

2 118

Pneumonia Deaths

South Dakota

Brown County

392

15 544

84 700

36

381

22

About 0.5% of Brown County’s population died of the epidemic, and perhaps ten times as many were ill, not to mention family members, friends, health care workers, and employers affected — the impact was exponential.

Many questions remain about the 1918 pandemic (some were answered after the virus was successfully reconstructed in 2005 and kept in a super-safe laboratory — a reality that surely inspired potential movie plots). The primary question is: Will there be another pandemic as deadly? In 2004, historian John Barry wrote that new pandemics are almost inevitable and quoted an influenza expert, “‘The clock is ticking; we just don’t know what time it is.’”

Today, we might feel as though the clock says 1918. There are many echoes of that pandemic in the COVID-19 outbreak. In one sense, it’s not surprising since whatever the virus, its drive to reproduce and biology are fundamentally the same. The interaction between people and health guidance is also very familiar. It’s worth noting that as of this writing, COVID-19 has already killed more Americans than any other single epidemic since the Spanish Flu (other than AIDS, an epidemic that began in 1981).

If you’re reading this, it means the right people in your lineage survived the 1918 pandemic. Most people did, of course, but one way or another the Spanish Flu touched almost everyone. Despite this, the public memory of the flu has not been well kept. Maybe it’s the sense of powerlessness and randomness, the lack of winners and too many victims. But people, families, tend to remember. It’s in our blood. //

Most of my research came from digital searches of Aberdeen newspapers of 1918-1919, primarily Aberdeen American, Aberdeen Daily News, and Aberdeen Weekly News (to save space, newspaper sources of individual quotations are not identified in text). Books noted in the text provided valuable overviews of the world and U.S. experience. Articles, including “I Had a Bird Named Enza (The Spanish Flue in the Dakotas, 1918),” a 2014 Dakota Conference paper by Charles T. Wise, and “1918 Flu Pandemic in South Dakota Remembered,” a South Dakota State Historical Society brief by Matthew T. Reitzel, were helpful in framing the statewide story. Thanks to the K.O. Lee Aberdeen Public Library, Dacotah Prairie Museum, Presentation Convent Archives, and others for their assistance.

Reporting of local and state cases shared just numbers, not people’s names. Names came in obituaries but also in the personal news notes that appeared in papers under headings such as “City in Brief” — the almost trivial tidbits of comings and goings, e.g., who’s visiting Aberdeen, who returned from vacation, and who is dealing with influenza. In fall 1918, almost every issue of every paper’s version of City in Brief included news about the flu. The following come from the Aberdeen Daily News.

Nine cases of Spanish influenza have been reported in Aberdeen during the past two days, one of them being at the home of a man named Ernst at 506 North First street.

Mrs. T. C. Bonney, who is confined to the hospital with an attack of the influenza, is reported to be much improved today. Mrs. Bonney was at Graham hall, before her illness, helping to nurse the patients who were suffering from the epidemic when she was taken ill.

Mrs. J.E. Bing, who has been spending some time at Athol, where she has assisted in caring for her folks, who have been very ill, has returned to Aberdeen. While at home she cared for two pneumonia patients and four influenza patients, one of them a baby, succumbing to the disease.

Dr. Owen King made a professional visit at Onaka Tuesday and reports influenza and pneumonia in that section [to be] very bad. Several entire families are stricken with it.

Mrs. P.J. Coffey of Sioux Falls and Miss Nora and Joseph Haley of Madison are in the city at the bedside of Miss Gertrude Haley, who is ill with pneumonia. Miss Haley is a nurse in training at St. Luke’s hospital.

Timothy Ronayne has arrived home from Omaha, Neb., where he has been attending Creighton college and will remain at home until school has opened again, it being closed while the epidemic of influenza is raging through the country.

R.C. Fauss has recovered again from influenza enough to be able to fit his duties as city mail carrier. He came back a few days ago but was again taken sick. During his absence his place has been filled by Professor M.S. Hallman, principal of the high school.