17 minute read

THE LEGACY OF SENATOR JAMES KYLE

MEET THE FIRST ABERDEEN RESIDENT TO GO VIRAL, LONG BEFORE GOING VIRAL WAS EVEN A THING.

by TROY MCQUILLEN

Advertisement

IMAGINE A HOT, 1890 Fourth of July political rally. All the gentlemen in their coats, ties, and hats; women in their petticoats, corsets, and hats. A master of ceremonies paces back and forth on a stage, nervously checking his watch. Seems the main-event speaker failed to show. Finally, he gives up and approaches a congregational minister, who was new to the area, seated nearby. He says, in so many words, “Reverend Kyle, we are in a fix. Our speaker has failed to come. We can’t wait any longer. Preacher, I know this is asking a lot, but will you give the speech?”

Crops had been consistently failing during these times, and the people were ready for something new in terms of political leanings and leadership. That’s why a county convention of reformers had gathered for a street rally on this Independence Day holiday. Reverend Kyle did oblige to say a few words to the restless crowd. When he was finished, news of his speech instantly went viral. One newspaper article reported, “The minister responded with alacrity. As he waded in, his hearers began to realize that Kyle had a speech. Curiosity gave way to fascination that soon turned to enthusiastic amazement.”

Within weeks, Populists selected him to represent Brown County in the state Senate. After beginning his term in January 1891, the Populists and Democrats joined forces and nominated him for a vacant Senate seat in the U.S. Congress. He quickly entered the Senate that same year.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

WHO WAS JAMES KYLE? James Henderson Kyle was born in 1854 in Xenia, Ohio, near Cedarville. His family moved to Illinois, where he grew up and entered the University of Illinois Engineering Department in 1872. A year later, he was back in Ohio, graduating from college in 1878.

While preparing admission to the bar, he answered a call and turned his life toward ministry. In 1881 he married Anna Isabelle Dugot, whom he had met while they both were attending Oberlin College. He graduated from seminary in Pennsylvania in 1882. During his seminary studies, he also taught engineering. Later, he moved to Utah and continued to teach and minister. That led to a calling at a church in Colorado. His wife then became ill and set their sights on Dakota Territory as a place to recuperate. They arrived in Ipswich, Dakota Territory, in 1885. Four years later, in 1889 (the same year as our statehood), he became the pastor of Plymouth Congregation Church in Aberdeen. He also served as financial secretary for the only congregational college in Dakota, Yankton College. By all accounts, his parishioners loved him. He was kind, he listened, and he identified with the pioneering struggles of the territory. By this time, he and Anna had one daughter, Ethelwyn, and had lost two other daughters in infancy. The Kyle’s took up residence at 313 S. Kline Street. Later, in 1900, James H. Kyle Jr. would be born.

FROM REVEREND TO SENATOR Interestingly, in an obscure article published later on by the Philadelphia Times, Kyle’s wife, Anna, tells the story of his viral speech with a bit more interest. She states, after the speech, he took off to Boston. While he was away, the locals came to their house to get Kyle’s acceptance to fill the state Senate position. Anna, completely without Kyle’s consent, agreed that he would be a candidate. Previously he had explained to her, and the locals, that he was but a mere minister, not a politician. As it turns out, Anna was a very influential woman who also carved out her own career in public service.

By the time Kyle entered the Senate, politically charged enthusiasts had painted him a Populist. The Democrats embraced him, yet he considered himself an Independent. However, after his first term in Congress, he seemed to be falling out of favor with the Democrats and the Populists. In 1896, the Populists controlled Congress, and it was presumed Kyle would succeed himself in the election. Growing dissonance among his party caused him to stray from the faction. In doing so, the Republicans took note and ultimately cast their votes for Kyle. Combined with a favorable showing of Democrat support, he easily won

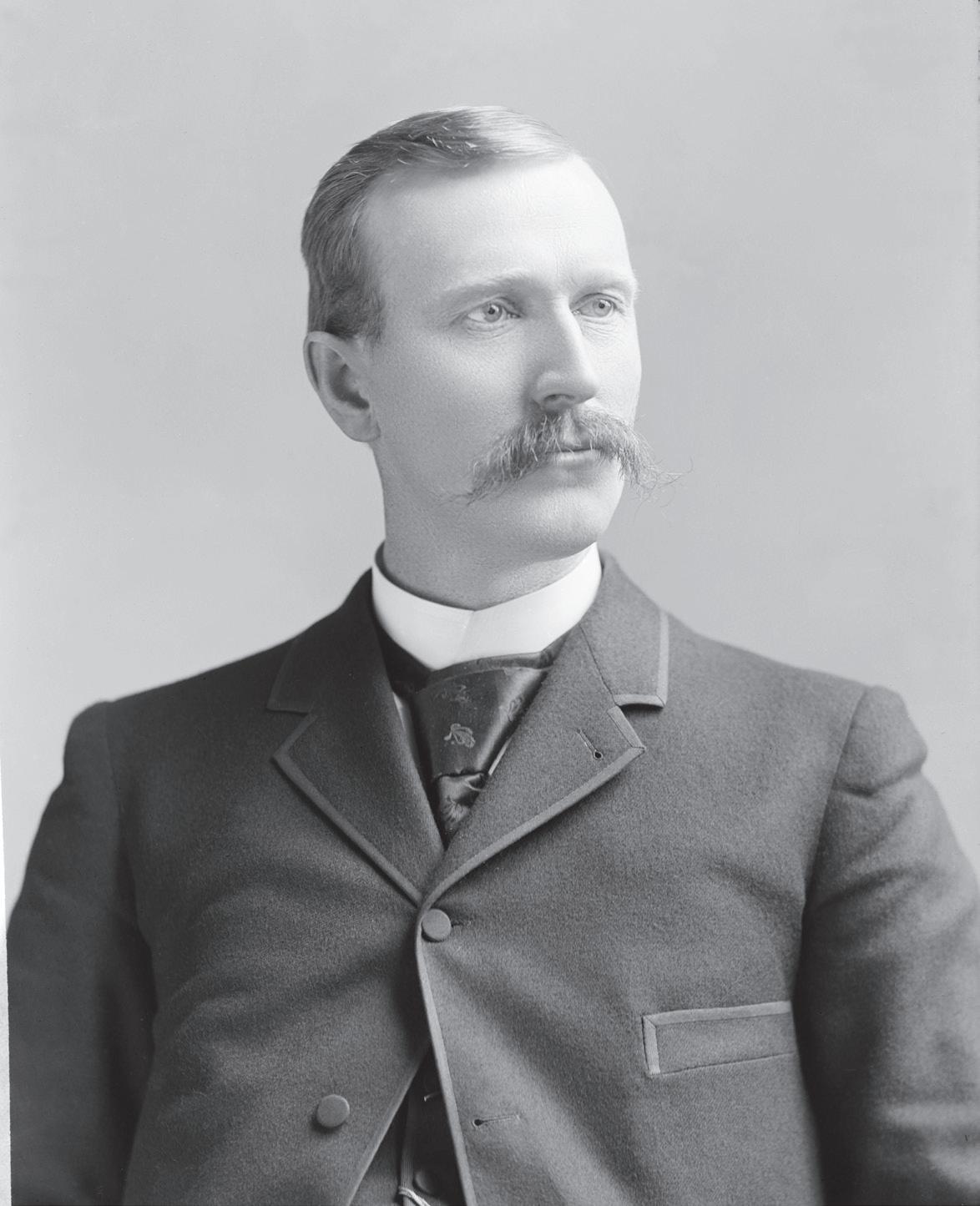

Portrait of a brand new Senator. Senator James H. Kyle, photographed by C.M. Bell, 1891, Library of Congress.

Through Senator James H. Kyle’s efforts, this glorious post office/U.S. courthouse opened in 1904 on the corner of Main Street and 4th Avenue. When people see historic pictures of Main Street from Aberdeen’s early days, most confuse this building with the one on the corner of Main and 2nd Avenue (once First

National Bank and Stewarts School of Hairstyling).

The reality was, the 1904 post office was almost four times the size of the First National Bank building. It was closed in 1937 and razed in 1944.

This photo was given to the author by Syndey Ranney, whose family goes back to Aberdeen’s early days. The stunning quality of this photo is what inspired this story. It is interesting to note the trolley car tracks.

The streetcars would enter and exit Main Street from this corner. From here, the tracks went east one block to Lincoln Street, then turned south toward Northern.

The scene depicted probably dates to around 1912.

This corner is best known as the home of JCPenney (inset), a tenant in the Midwest Building, which still stands here today (now RhodesAnderson Insurance).

reelection in 1897, but with allegiance to a different party. From then on, Kyle considered himself a Republican for the rest of his short life.

During his time in office, Kyle acted as chairman for the Great Industrial Commission for several years. The commission was charged with investigating questions pertaining to immigration, labor, agriculture, manufacturing, and business. The purpose was “to suggest such laws as may be made the basis of uniform legislation by the various States of the Union, in order to harmonize conflicting interests and be equitable to the laborer, the employer, the producer, and the consumer.” (The North American Review, June 1899.)

He also served on the Indian Affairs Committee and worked toward securing opportunities for employment for American Indians. He was promised the chair of the committee on territories but died before the next session started. He had been an active member of the committee and worked tirelessly on scores of laws that governed the territory of Alaska. Kyle was also a member of the committee on pensions, and his work there contributed to benefits for thousands of veterans.

Additionally, he served on committees for irrigation and reclamation of arid lands, Indian depredations, forest reservations, and game protection. The town of Kyle, South Dakota, is named after him.

Last but not least, Kyle was chairman of the Education and Labor Committee and was wildly applauded by labor groups who thanked him for what he did in the name of labor and education. On June 28, 1894, President Cleveland signed bill S.730 created by Kyle. It decreed that the first Monday of September will be celebrated as Labor’s Holiday and become an official holiday like Christmas, New Year’s, and the Fourth of July. We now know it as Labor Day.

As you can see, the minister from Plymouth Congregation, James Kyle, was a busy guy.

LOBBYING FOR ABERDEEN Aberdeen got started in 1881. Eight years later, South Dakota became a state. The competition was fierce for state capitals, and when Aberdeen did not receive capital status as it had hoped, general competition among South Dakota cities became even more aggressive. Many community leaders knew what it took to become a regional hub. Community amenities and essentials like municipal water, sewer, and electricity eventually came, often instigated by private individuals. Housing developments sprang up, and downtown evolved with large, multi-story brick buildings.

Senator Kyle always had Aberdeen’s best interest in mind. At the time, Aberdeen did not have a dedicated post office building. It was always inside an established business and moved at least seven times before a permanent home for it was built. The increased activity due to the railroad traffic and business caused the most strain on the post office. Something had to be done. While I can find no direct lobbying from locals, it probably would be fair to say that local, prominent business people, who were tired of the post office being inside their businesses, encouraged Kyle to do something about it.

Kyle introduced a bill in 1897 that would appropriate $87,000 for a grand scale federal courthouse/post office building to be built in Aberdeen. It immediately passed the Senate. The House, for some reason, didn’t pass it until 1899. Then, the legislation got stalled for two years. In the meantime, Aberdeen was growing rapidly, so it was decided that $100,000 was needed for the new building. The amendment cleared both Houses and was signed into law by President McKinley on March 3, 1901. However, due to Aberdeen’s projected growth, the measure

increased to $175,000 and was again approved by the president. Construction commenced in March 1903, and the building opened on September 26, 1904. The first term of the U.S. District Court began on November 8, 1904.

Upon signing the initial bill into law in 1897, funding the building, President McKinley handed the pen he signed the bill with over to Senator Kyle. It was placed on display in the post office.

The location selected for this glorious building was on the corner of Main Street and 4th Avenue. It was designed to be a modern, efficient icon of community pride. Just two blocks away, another building that Kyle was instrumental in establishing was also being planned, Aberdeen’s new Carnegie Library. Kyle had successfully secured a $15,000 grant from Andrew Carnegie for the new endeavor. A personal letter to Kyle from Carnegie’s office kindly asked that the library be named for Carnegie’s boyhood friend and former president of the Milwaukee Railroad, Alexander Mitchell, who had passed away in 1887.

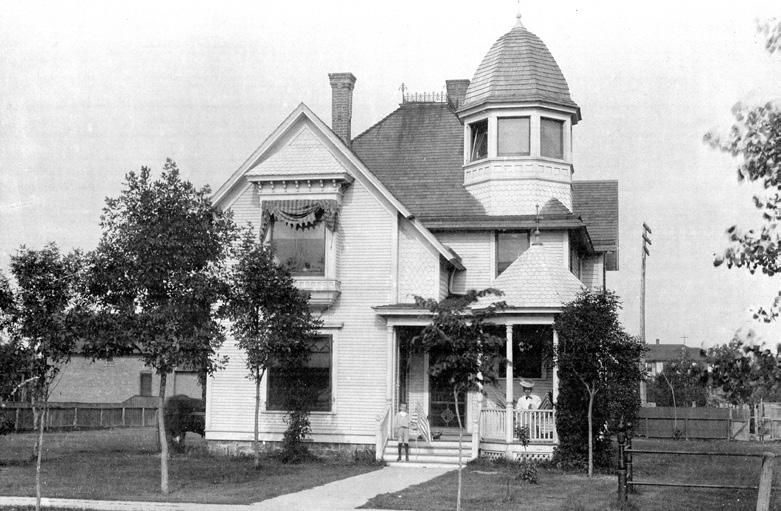

This is the house that Anna Kyle and her children moved into after the Senator died in 1901. Anna is seen on the porch, and James Jr. (born in 1900) stands holding an American flag. The house still stands at 311

S. Kline Street. However, the tower and porch are now gone. It was built in 1895. Photo provided by Ann Hein.

➼ HELP FROM THE FAMILY

Whenever I do stories on notable Aberdeen pioneers, I always look for living relatives. At the last minute, I found someone on Ancestry with ties to the Kyle family. I sent her a note and was happy to learn she is the great-granddaughter of Senator James Kyle. She has concentrated much of her research on Kyle’s wife, Anna (pictured), an amazing woman in her own right. I would like to thank Ann Hein for her insight and photos.

Upon the Senator’s death, Anna Kyle, along with her children Ethelwyn and James Jr., moved into the Victorian house on Kline Street, right beside their family house. Ms. Hein says that both Kyle homes were built without kitchens. Anna died in Aberdeen in 1920, but Ethelwyn and James Jr. took off to the west.

Anna Kyle can be faintly seen in the carriage in this picture. This is the house the Senator and his family lived in while in Aberdeen. Located at 313 S. Kline, it was built in 1887 and is still standing today. Photo provided by Ann Hein.

Unfortunately, Kyle died in 1901 without seeing the fruits of these efforts. The library was only in the planning phases at the time of his death.

A TRUE PUBLIC BUILDING The vast majority of the people used Kyle’s government building as a post office, which was on the first floor along with the land office. Other offices included the United States Court on the second floor, with rooms for the judge, district attorney, witnesses, marshal, and others. The IRS was also on the second floor. The third floor housed space for the jury, rooms for the railway mail service, and room to grow.

It was a steel structure “skinned” with Kasota limestone veneer. The basement foundation was made of granite from Milbank. In 1926, an addition was added to alleviate overcrowding and better accommodate the growing volume of mail.

In August 1935, talks began among the Aberdeen business community about the need

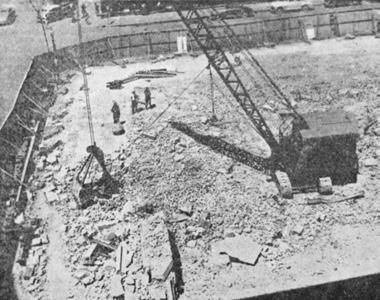

for a new federal building. The postal demands continued to grow and challenge the current building. Some other reasons cited for a new building included increased parking (there were more cars by now) and the need for a large loading dock with better street access. One key reason, however, was the opportunity provided by resources from the WPA and other re-employment programs. Even though the current post office worked, the city didn’t want to lose out on funds that could end up going to a different community. $400,000 was appropriated by Congress, and a new post office courthouse building was completed and opened for business in 1937 on Fourth Avenue. At the same time, Senator Kyle’s building on Main Street was shut down. It stayed locked up and vacant for many years. Then in 1944, Mayor O.M. Tiffany is seen swinging a pickaxe signifying the initial blow of the building’s demolition.

Demolition? How could a massive stone building that embodied community spirit and growth be slated for razing? Because of war. At the time of its closing, the building was turned over to the Salvage Bureau, a division of the Treasury Department who apparently did nothing with it. An assessment of the building revealed that fasteners that held the masonry together were failing, the roof was leaking, internally routed rain gutters burst, floors were buckling, and ceilings caved in. It was determined that Aberdeen could contribute greatly to the war effort with salvage from the building rather than wait for a developer who probably couldn’t justify the repairs.

The steel girders were of quality steel that was in demand for battleships. After everything usable from the inside was removed, one of the first tasks of demolition was for torchmen to sever connections of steel girders. A massive crane was brought onsite to smash through the walls. What most people didn’t realize was the building was not constructed of massive stones but rather limestone veneer that was only five or six inches thick. The stone slabs were fastened to the superstructure with steel strapping. Thus, the stone cracked very easily and was useless as salvage. After the tin was removed from the roof and the girders were pulled out (about 200 tons worth), along with heavy vault doors, the building was strategically pushed down and into its own basement. A six-inch layer of soil was compacted on top of the grave, and that was that. Senator Kyle’s legacy was gone. Other items salvaged included brass, copper, lead, zinc, and aluminum. Wood was also saved. The demolition of the building was a several month spectacle, often drawing large crowds of onlookers.

It seems rather odd that a prime location on Main Street would have a three-story building buried just beneath the surface. Officials affirmed that if anyone were to excavate on the site, it would be easier than virgin soil because the rubble beneath was rather loose and can be removed more easily. And that happened just six years later when Fred Hatterscheidt began work on the now standing Midwest Building designed to house JCPenney, then Woolworths, a year later.

A legend that surrounds the rubble from the post office rears up on Facebook quite often. Local lore states that large stones from

Mayor O.M. Tiffany (second from left) was photographed in May 1944 taking a symbolic swing at the post office building, kicking off the demolition. The demolition would last several weeks and was wrapped up in August.

Most all the pictures were taken looking north from the

Capitol Theatre building. These photos are from the

Aberdeen American News from May through August, 1944, made available from the Dacotah Prairie Museum.

➼ WHAT HAPPENED TO THE PEN?

If you carefully read this story, you may have happened upon the same question I did when researching. If the pen President McKinley used to sign the post office appropriation bill was given to Senator Kyle, and it was then put on display in the building, where did it go when the building was razed? An article at the time of demolition says it was entrusted to the post office archives. I have been in touch with the GSA to see if they can track it down. Stay tuned.

This is the letter from Andrew Carnegie’s staff to Senator

Kyle announcing a $15,000 grant to fund the construction of a new public library building to be built on Sixth Avenue

SE and Lincoln Street in Aberdeen. It is dated March 14, 1901. The Senator unexpectedly passed away a few months later, never seeing the finished building. The letter is on display at the K.O. Lee Aberdeen Public Library.

the building were placed around Wylie Lake for people to sit on while fishing. Articles do mention that most of the building was buried on site and compacted by the crane. But articles do say some rubble was carted off. Perhaps during the construction of the Midwest Building (home of JC Penney) in 1950-1951 excavated rubble was taken to Wylie Lake.

Surely the post office needs drove the desire for a substantial federal structure, but the Federal Court also provided a draw for Aberdeen and still does to this day. According to U.S. District Judge Charles Kornmann, the U.S. District Court continues to draw a large, diverse crowd of visitors to Aberdeen. He says it was quite typical back in the day to include a courtroom with a federal post office in the same building. He suspects Senator Kyle knew that a Federal Court would be a substantial feather in the cap for the growing Hub City.

GONE TOO SOON Senator Kyle was one of the most beloved citizens of the Hub City during his time. Tragically, he died at age 47 on July 1, 1901. The Aberdeen Weekly News reported that even though his death was imminent after a threeweek illness, “…the announcement that the end had come caused a shock to the people of Aberdeen such as they have never before experienced, and it brought sorrow to every heart within the limits of the city – a sorrow that is seldom felt except for a father or mother.” The cause of death was attributed to Bright’s disease along with heart complications causing pulmonary hemorrhages.

Kyle’s funeral was a national affair, held here in Aberdeen. Vice President Teddy Roosevelt appointed 13 Senators to attend the ceremony, which began at the Kyle house on Kline Street. From there, they processed to the Grain Palace at the corner of 5th and Main Street. The Grain Palace was lavishly adorned with flowers and packed with people. After the service, Kyle’s body was escorted to Riverside Cemetery in a procession of carriages reported to be over a mile long. He was buried alongside his two infant daughters on July 4, 1901, just eleven years after delivering his impromptu speech that forever diverted his career and made an indelible stamp on the city of Aberdeen. //

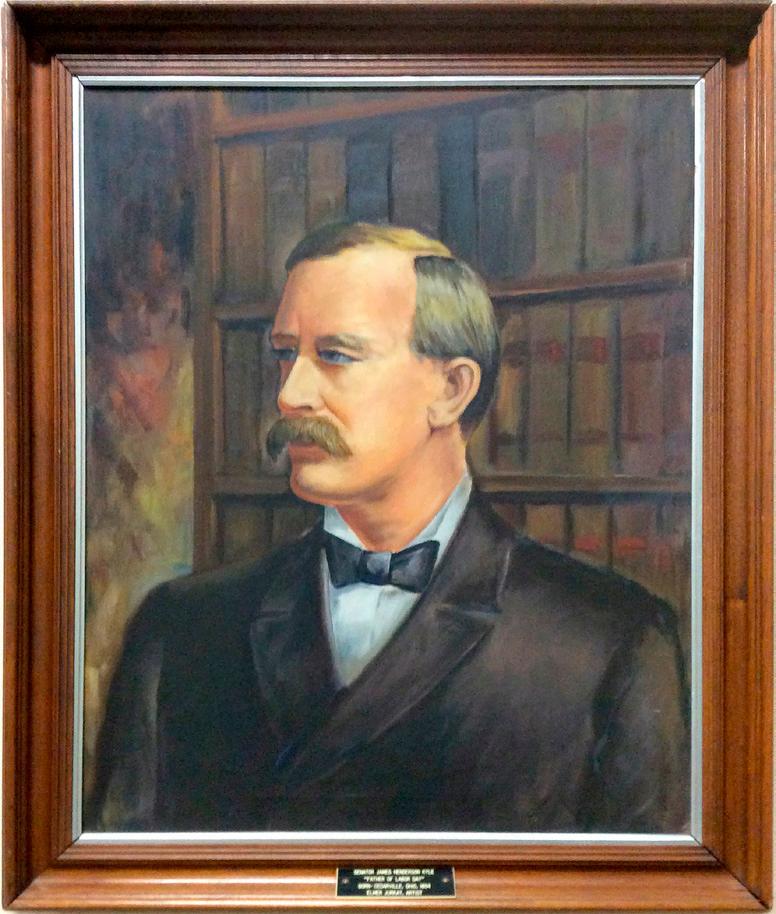

The folks of Cedarville, Ohio,

Senator Kyle’s birthplace, hold a special affinity for him as well.

In 1947, a portrait was painted as part of a commemoration ceremony honoring Kyle’s efforts in creating Labor Day. The folks at Cedarville University were kind enough to send us a picture of the portrait that still hangs in their library. Portrait by Elmer

Jurkat, photo by Lynn Brock.

Much of the information for this story was sourced from early newspapers from Aberdeen. Clippings were found at the K.O. Lee Aberdeen Public Library as well as online. Particular newspapers include the Aberdeen Daily News (1938) and the Aberdeen Weekly News (1901). A chapter was devoted to Senator Kyle in Edwin Torrey’s book, Early Days in Dakota, 1925. As always, many thanks to the Dacotah Prairie Museum for allowing us to publish their archival photographs. I am appreciative of Barbara Paepke and U.S. District Judge Charles Kornmann for their help in better understanding the District Court here in Aberdeen.