14 minute read

UNDERSTANDING THE IMPACT OF VISUAL CULTURE

from SLA Spring 2021

Understanding the Impact of Visual Culture AN INTERVIEW WITHElizabeth Hill Boone

PROFESSOR OF ART HISTORY AND MARTHA AND DONALD ROBERTSON CHAIR IN LATIN AMERICAN ART

Advertisement

Professor Elizabeth Hill Boone has contributed groundbreaking research in the field of art history for more than 40 years. A specialist in Pre-Columbian and early colonial art of Latin America, Boone is a former Director of Pre-Columbian Studies at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C., was the Andrew W. Mellon Professor at the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art, and has been awarded Mexico’s Order of the Aztec Eagle, the College Art Association’s Distinguished Scholar, and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society for Ethnohistory. She is also a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Mexican Academy of History. This spring, Boone will retire after a 26-year tenure in Tulane University’s Newcomb Art Department.

EMILY WILKERSON (EW): When did you first realize you wanted to study the history of art?

ELIZABETH HILL BOONE (EHB): I was a sophomore in college. Although I started out in marine biology, I was drawn to art. I found ancient Egyptian and Greek art to be especially compelling because these were expressions of peoples somewhat like us, but also culturally different from us.

EW: What drew you to Pre-Columbian art history, in particular?

EHB: My sculpture professor Karl Rosenberg at the College of William & Mary taught a course on ancient sculpture in which he devoted three weeks to Pre-Columbian art. I remember when he showed us the monumental sculpture of a monstrous creature— the Coatlicue sculpture, which was said to be the Aztec’s mother goddess. She was figurally horrific, with her head and hands replaced by great serpents and a skirt of intertwined rattlesnakes. I came to wonder how this could be—what kind of mind has such an image at its mother goddess? I spent some of my early career working toward the answer to that question.

EW: How does art history inform our understanding of life today?

EHB: Art history gives us the skills to see, and to evaluate what we are seeing. It trains us to look, notice difference, and judge critically. Additionally, art history tracks major historical and social movements/trends and reveals them through the visual expressions of that time. We see Egypt not through the texts of papyrus scrolls but through the pyramids, sculptures, and tomb paintings; we see the Italian Renaissance not through written documents but through the explorations and achievements—scientific as well as cultural and social—of its artists; and we see the Aztecs through their great sculptures and painted books.

Art history is the perfect disciplinary major because it draws on the approaches of history, archaeology, linguistics, literary studies, critical theory, and sociology, among others. It is ecumenical in the way it draws on different approaches to understanding visual culture. Moreover—and this is especially important today in our increasingly visual world—art history teaches us how to evaluate the way images shape our thinking and can manipulate us, for good or bad.

EW: You’ve published five books in the last ten years on writing and pictography in Mexico, in addition to numerous published articles. How does writing fit into art history—a discipline largely understood as image-based?

EHB: Artists use images to think and express themselves, but most others largely think and express themselves through language. Our expression becomes more permanent when we write it down because writing is a medium that allows discourse across location and time. We write for the future and for others not present at the moment of our writing. And, of course, this includes those who write alphabetically to record spoken languages, but also mathematicians and physicists who use algebraic notation, or composers who write musical scores.

My own intellectual project has been to understand and explain the system of Mexican pictography, and particularly how the Aztecs used figural images to record their past history, their present world, and its future possibilities. In a research project, as I begin thinking about the corpus of images I am studying, the practice of writing (and all that goes into it, from outlines to drafts) allows me

PROFESSOR ELIZABETH HILL BOONE. PHOTO BY PAULA BURCH-CELENTANO.

to organize, analyze, and essentially make sense of these ancient human expressions. I write to solve problems, and then to convey this information to others.

EW: What are some of the changes you’ve seen in field over the 40+ years you’ve been an art historian?

EHB: In the field of art history—and much of academia—the most obvious change has been the gender rebalance. When I went to college, it was rare to have a female professor; almost all our teachers were men, and women were not taken seriously as scholars or professors. The women’s liberation movement of the late 1960s through 1980s changed this, and although women are still largely the caregivers of their children, they are also researchers and professors. Our art history program, for example, has one male professor and eleven females, five of whom are also mothers of young children.

In the field of Pre-Columbian Studies, I would say the greatest change has been the critical intervention of art historians, and not just archaeologists, as interpreters of ancient American cultures. And art history as a discipline has also changed in its goals and reach. It has transitioned from its former focus on Western Europe to a new emphasis on non-Western and global perspectives and a concern with images and objects not previously embraced in the concept of fine art. It is an exciting time to be an art historian.

EW: You’ve received awards such as Mexico’s Order of the Aztec Eagle (1990), the College Art Association’s (CAA) Distinguished Scholar (2019), and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society for Ethnohistory (2019). What do these awards mean for you, your work, and your discipline?

EHB: I am very honored to have been recognized for my work, and I think also for my students’ success, of which I am very proud. It was exciting to be recognized by Mexico in 1990 for promoting Aztec culture in a path-breaking exhibition at the National Gallery of Art and a coordinated symposium on the spectacular finds when the Aztec Great Temple was just beginning to be excavated. More recently, it was especially gratifying to see the CAA recognize a Latin Americanist and Pre-Columbianist as the distinguished scholar, when 40 years prior we Latin Americanists had to fight for CAA recognition and to have even a single session on the topic at the annual meeting. This shows us how far the field has come.

I have been very fortunate to have participated in the development of Pre-Columbian and early colonial studies as a field of art historical endeavor. The Ethnohistory award, I think, recognizes the importance of insisting that Mexican pictographic writing should be understood as a discourse system roughly parallel to Western writing so that Pre-Columbian and early colonial history can be told through their painted books.

BARRO NEGRO (BLACK CLAY) POTTERY MADE BY INDIGENOUS ARTISANS IN THE OAXACA REGION OF MEXICO, ALONGSIDE A FAMILY PHOTOGRAPH, HOLD SPECIAL MEANING IN THE HOME OF ELIZABETH HILL BOONE, A PROFESSOR IN THE NEWCOMB ART DEPARTMENT, AND JOHN VERANO, A PROFESSOR IN THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY. PHOTO BY PAULA BURCH-CELENTANO.

EW: What do you most love about teaching, and what has been one of your favorite moments teaching at Tulane?

EHB: I love seeing students’ eyes light up when they see and understand something entirely new, when they can read an image for the first time and come to know its cultural message, and when the material I teach challenges their assumptions about the way life is, or was. My classes usually ask students to extend beyond their own cultural perspectives. Probably the most fun is in my seminar on Mexican manuscript painting when the students study the graphic vocabulary and organizational structures of painted histories and then create their own painted histories using the ancient principles.

EW: From your perspective, why are the liberal arts important?

EHB: It is important to understand how we came to be who we are as a culture: how things from the past have shaped who we are, and how social and cultural forces in the present also determine this. For me also, it is crucial that we learn to think critically and understand how discourses of various sorts (speeches, sound bites, writings, tweets, and images) can affect us and others; and we need to be able to judge what this influence is and how we should respond to it. The liberal arts give us these skills.

Boone’s newest book, Descendants of Aztec Pictography: The Cultural Encyclopedias of Sixteenth-Century Mexico, was published by University of Texas Press in 2021.

Tenenbaum Sophomore Tutorials

With a focus on interdisciplinary research that responds to the current moment, the Tenenbaum Sophomore Tutorials bring together faculty and students in ideal conditions for intellectual exchange over the course of two consecutive semesters.

Each fall semester, 12 students join two professors selected from the School of Liberal Arts research faculty in a team-taught seminar on a special topic highlighting approaches from the humanities and social sciences on issues that resonate in the region. Students participating in the program meet weekly throughout the fall for their seminar and also biweekly in individual sessions with one of the professors for a tutorial-style discussion. This model equips students with an atmosphere for engaged learning and discussion while preparing sophomores for original inquiry and research in the humanities.

The spring term builds on the tutorial-style relationship and helps students strengthen written and oral communication skills as they pursue independent research projects. Committed to furthering original research, the program pairs each student with a faculty fellow and provides a monetary stiped. Students’ work with faculty may result in written papers or creative work, which is presented at the close of the academic year in a symposium attended by students, Tenenbaum faculty fellows, and invited guests.

The Tenenbaum Sophomore Tutorials began in 2020 with Adrian Anagnost, an art history professor in the Newcomb Art Department, and Marline Otte, a professor in the Department of History, leading the course “Monuments and Public Memory.” From the disciplinary vantage points of history and art history and spanning research across multiple decades, this course considered the role of public art and monuments in modern cities of the West, with a special emphasis on New Orleans. Students from across the university—from the liberal arts and public health to architecture—participated in the program’s inaugural iteration.

Find out more information on this new, exciting program at liberalarts.tulane.edu/tenenbaum.

Graduate Student Pedagogy

While research is the primary focus during a graduate student’s tenure at Tulane, teaching will most likely be a primary job requirement upon graduation. Additionally, the opportunity to teach or lecture often becomes available while still in school. The Center for Learning and Teaching (CELT) initiated the three-course Graduate Student Pedagogy Program in 2020 to prepare graduate students for the job market and beyond. With the goal of providing a foundation for excellence in teaching, students gain three credit hours through the following courses in the program:

In “The Essentials of Learning and Teaching” students explore the science of learning, evaluate different course designs, discuss ways to ensure inclusive and diverse classroom environments, and learn about the pedagogy of service learning.

Throughout “Practical Course Design and Teaching Skills,” students focus on the practical applications of course design, classroom management techniques, the appropriate inclusion of technology, and the development of learning-based assessments.

Lastly, in their “Teaching Practicum,” graduate students gain hands on experience as faculty of record for a course in their department, as a guest lecturer, or give lectures to peers. All graduate students receive feedback on actual teaching opportunities from peers and mentors.

Afro-Mexicans:

Illuminating the Invisible from Past to Present

BY BEAU D.J. GAITORS PH.D. ’17, HISTORY

Mexico. Take a moment to think about the movies and images you have viewed that reference groups of people in the history of Mexico. You may recall images of the Aztecs, the Mayans, or Spanish conquistadors. These images present conflicts between a Spanish and an indigenous past: two roots that fused to form a national identity. Yet, in other Latin American countries the images of the nation incorporate a third root: African descendants. African influences are seen and felt in Brazil from Candomblé to Capoeira; in Cuba through Santeria and Salsa; and in Peruvian music and their Pacific coast communities. The African presence extends through Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, Venezuela, and throughout Latin America.

Despite the dominant narrative, African descendants also have a history and presence in Mexico. In 2015, the Mexican government conducted an interim census that incorporated African descendants into the categories of race and ethnicity, which had not been done since the 1830s. Citizens had the opportunity to self-identify and almost two million people identified as African descendant. After the results of the 2015 census were released, media outlets immediately questioned where African descendants in the interim census came from, some speculating that they were recent immigrants from West Africa or from the Caribbean.

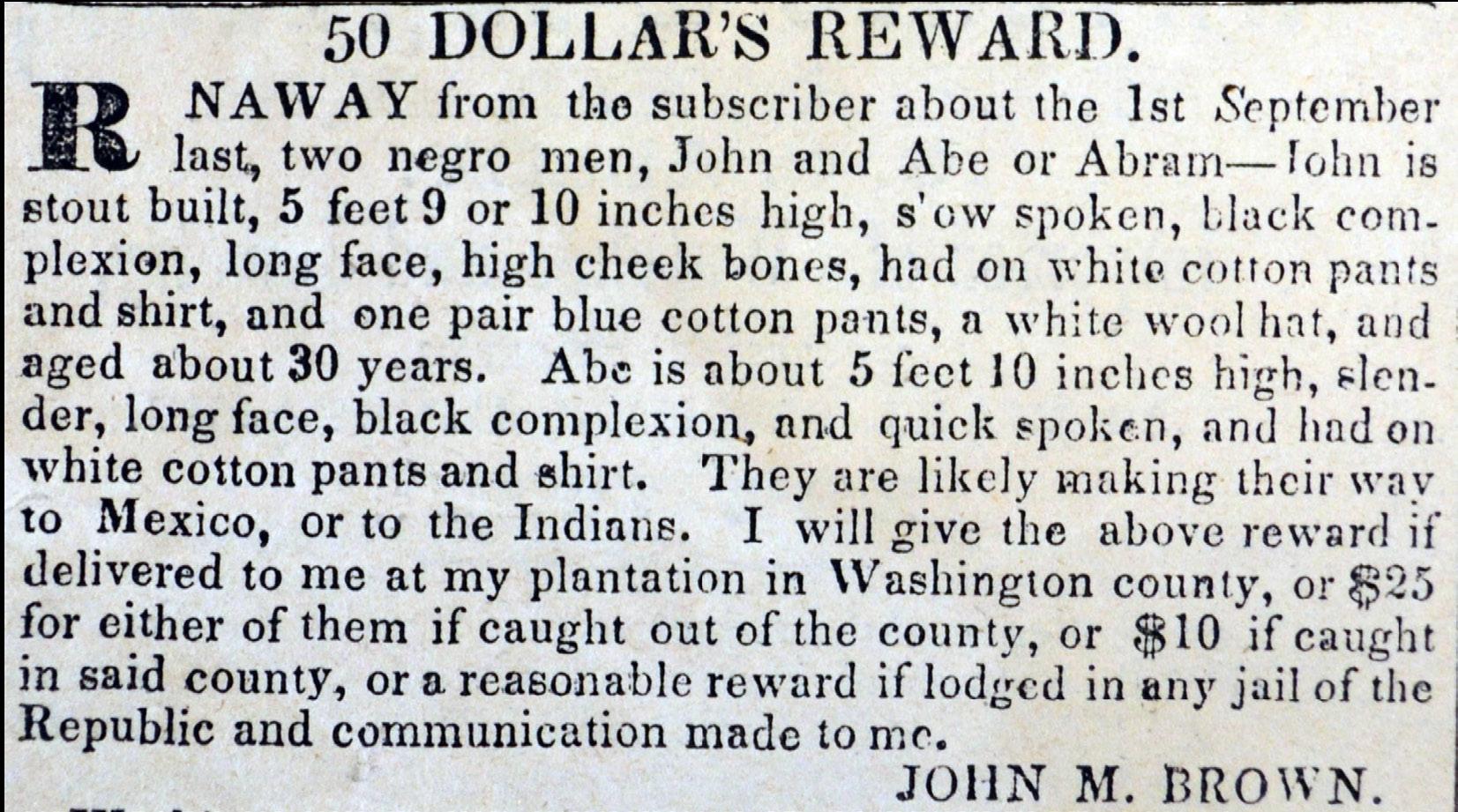

The longer history was little appreciated. In the 1500s and early 1600s, New Spain (colonial Mexico) had one of the highest importation rates of enslaved Africans to the Americas leading to large populations in cities. In their first decade of independence, the Mexican government abolished the slave trade in 1824 and the institution of slavery in 1829. As a result, countless African Americans in the southern U.S. took advantage of this new law and participated in the southern route of the Underground Railroad fleeing to their neighbor, Mexico—quite contrary to the standard narrative of slaves seeking freedom north.

For example, on July 7, 1839, twenty-seven passengers boarded a merchant ship in New Orleans. They exited the ship in the Mexican port city of Tampico. Among the passengers were seven African Americans whose passport status in Mexico listed them as enslaved. These African Americans had traversed the Gulf, hidden on a merchant ship that took them from enslavement in the U.S. to newfound freedom in Mexico. They practiced their own agency and took advantage of the abolition of slavery in Mexico. Passport records of New Orleans from 1830 to 1840 combined with Mexican importation logs reveal a significant number of enslaved and free African Americans who moved to Mexico.

Many of the African Americans remained in the port cities and found employment in the shipping arena and marketplaces, joining the African descendant communities already present in Mexico. African descendants contributed to society in various ways, including through their occupations as dock workers, vendors, in the military, and as shop owners, and became integral to every aspect of life in Mexico from their roles as political participants, to religious and artistic capacities.

As African descendants received state recognition in the interim census of 2015, and will be included going forward, the census should be used to do more than count their numeric presence. The Mexican census can help politicians, lawmakers, and citizens carefully assess issues affecting African descendants, such as access to resources, education, and other critical aspects of life throughout Mexico, which many communities are fighting for today. Although there seems to be minimal representation of Afro-Mexicans, the art of historical research challenges us to consider the past in connection with currentday circumstances to illuminate the “invisible,” not only to reveal the vibrant history of Afro-Mexicans, but to enhance the quality of life of present-day citizens as a model for social justice work for other forgotten groups and spaces.

THE FLIGHT OF ENSLAVED PEOPLE TO MEXICO RESULTED IN NOTICES LIKE THIS ONE THAT APPEARED IN THE NATIONAL VINDICATOR IN 1843.

EAST TEXAS DIGITAL ARCHIVES/ STEPHEN F. AUSTIN STATE UNIVERSITY.

DE MULATO Y MESTIZA, PRODUCE MULATO, ES TORNA ATRÁS. BY JUAN RODRÍGUEZ JUÁREZ, CIRCA 1715.

MEXICO WAS A SLAVE TRADING COUNTRY IN THE 16TH CENTURY, HAVING A POPULATION OF AROUND 200,000 PRINCIPALLY WEST AFRICAN SLAVES THAT OUTNUMBERED THE SPANISH COLONIALISTS FOR DECADES AND WAS FOR SOME TIME THE LARGEST IN THE AMERICAS. BLACK SLAVES WERE TYPICALLY USED BY THE SPANISH TO ACT AS FOREMEN, OVERSEEING THE INDIGENOUS POPULATIONS, AND MANY OF THE (MOSTLY MALE) SLAVE POPULATION WENT ON TO MARRY INDIGENOUS WOMEN. THEREFORE, AND DUE TO THE MANY RESULTING MIXED-RACE OFFSPRING, BLACK MEXICANS WERE ALL BUT FORGOTTEN ABOUT FOR CENTURIES, AS THEIR BLOODLINES MIXED WITH OTHER INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES AND MESTIZO PEOPLES OF MEXICO.

Beau D.J. Gaitors earned his Ph.D. in history from Tulane in 2017. His dissertation focused on traders in Veracruz during the transition to Mexican independence. He is an assistant professor in the Department of History at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, where he teaches Latin American history.