Blue Bolts & Wonder Boys

A Golden Age History of Novelty Press

by Mark Carlson-Ghost

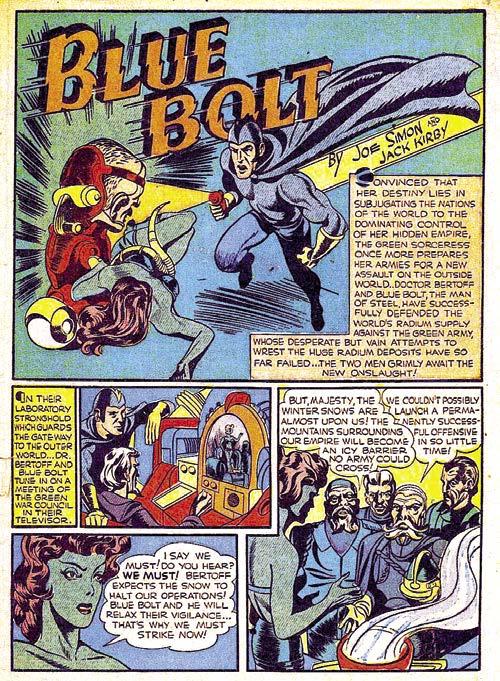

Like a bolt out of the blue, Novelty Press caught fire. A Blue Bolt, to be specific. Joe Simon’s dynamic new hero (along with his persistent adversary, the enchanting Green Sorceress) quickly captured readers’ fancy. “Spacehawk,” “Sub-Zero Man,” and “Dick Cole, the Wonder Boy” all debuted in a single issue, a few months later.

There was a palpable sense of a powerful new player in the world of comicbooks.

Yet it would also be hard to find a comics company whose story has so many different roots, roots necessary to dig up in order to fully understand what followed.

It has often been told how nearly every 1940s comicbook line, from Timely to Street & Smith and Fiction House, emerged from publishers of pulp magazines or other periodicals who lacked a certain pedigree. That said, what happens when the people behind the country’s most popular slick-paper magazine decide to enter that increasingly lucrative field?

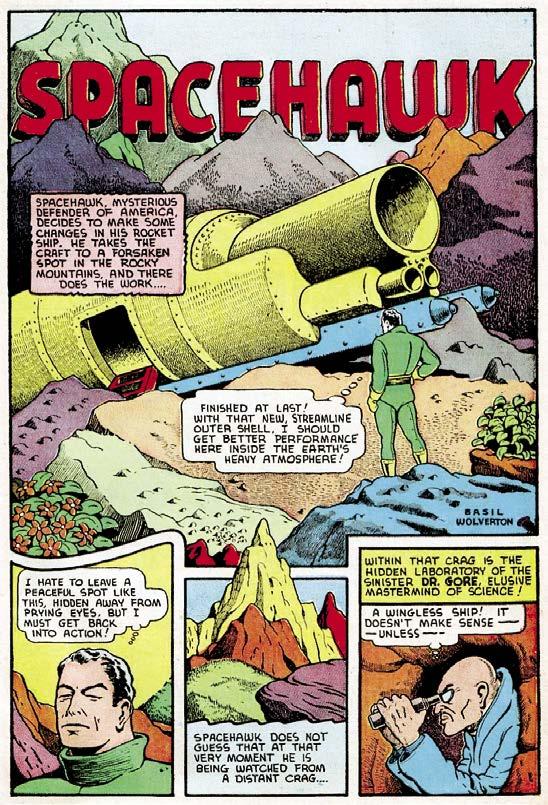

Novelty Press is the short answer, the home of Simon & Kirby’s “Blue Bolt” and Basil Wolverton’s “Spacehawk,” not to mention Carl Burgos’ “White Streak.” Yet the company’s attitude towards what it clearly considered lowbrow adventure would badly color its efforts. So would its reliance on an art shop whose product suffered a slow decline in quality over the years. Still, for a time, even before the launch of Novelty Press, Lloyd Jacquet’s Funnies, Inc., was a major force to be reckoned with.

Lloyd Jacquet & Funnies, Inc .

In the summer of 1939, Lloyd Jacquet broke away from his duties as editor of Centaur Publications to form an independent shop of artists and writers. His goal was to supply material for would-be comicbook publishers who didn’t wish to take the time and expense to establish creative staffs all their own.

Given the high mortality rate of comicbook titles, Jacquet argued, utilizing Funnies, Inc., only made sense.

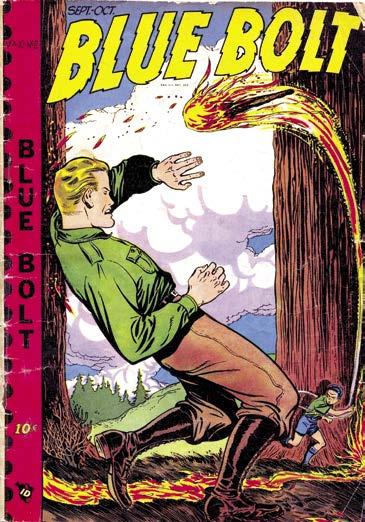

A Target On Their Backs

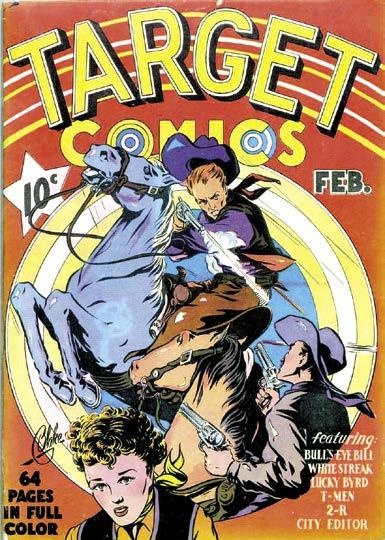

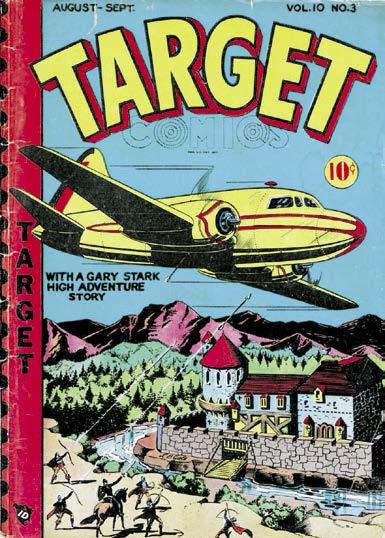

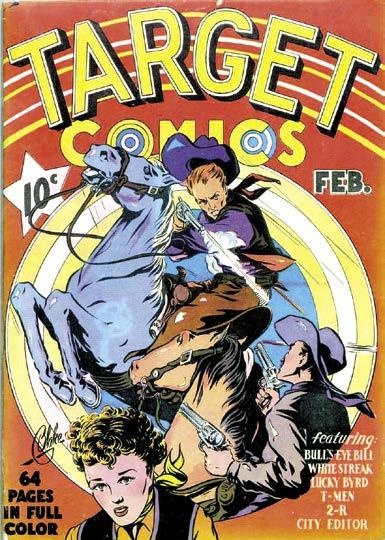

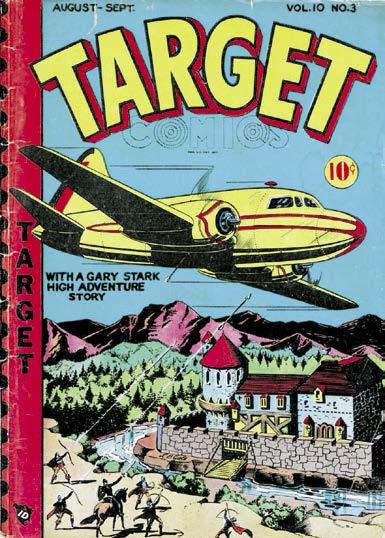

The covers of the first and final issues of Novelty’s Target Comics basically bookend Curtis Publishing’s comicbook experiment: from Vol. 1, #1 (coverdated Feb. 1940), fronted by a drawing of Bull’s-Eye Bill by Sub-Mariner creator Bill Everett (using his middle name “Blake”)—to Vol. 10, #3, a.k.a. #105 (Aug.-Sept. 1949), with a high-flying “Gary Stark” adventure highlighted by artist L.B. Cole. One or two Curtis/Novelty titles closed out with indicia that bore a “Sept.-Oct. 1949” date, and then it was all over. Thanks to the Grand Comics Database. [TM & © respective trademark & copyright holders.]

According to David Saunders’ excellent Pulp Artists website, Lloyd Jacquet was born in 1899. He served in World War I as a radio operator, seaman second class. After the war he worked for various newspapers, including The Brooklyn Daily Eagle and The New York Evening Mail. In 1927, Jacquet linked his two abiding interests, radio and journalism, hosting a radio program entitled Going to Press. The intersection of the two fields remained a benchmark of his career well into the ’30s.

By 1935, Jacquet’s association with The Brooklyn Daily Eagle led to his role as editor of New Fun, one of the earliest comicbooks and the first regularly published comic to feature material especially made for it. The Daily Eagle had agreed to let its presses print the new venture. Published by Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson, New Fun would ultimately lead to what became National, then DC Comics. As will be seen, Jacquet was involved with some of the most significant events of comicbook history.

Having gotten a taste for publishing, Jacquet joined H.D. Cushing and Harold Hersey to form C.J.H. Publications, a shortlived pulp magazine publisher, most notable for producing one-shot text versions of Flash Gordon, Tailspin Tommy, and Dan Dunn. Returning to the world of comicbooks in 1938, Jacquet became editor of what was generally known as the Centaur Comics Group. Working with a group of talented young writers and artists, he oversaw the creation of a number of super-heroes, all in an effort to duplicate at least some of the excitement generated by a sensational new fellow named Superman. Bill Everett’s Amazing-Man was the most notable of Centaur’s new characters.

3

But Jacquet was ambitious and dreamt of publishing his own comicbooks. While that never quite came to pass, it did lead to his leaving Centaur to create his own art shop, which he christened First Funnies, Inc. It wasn’t long before he dropped the First.

When Jacquet made the break, he took the best and the most talented creators working at Centaur with him. These included notables like Everett, Carl Burgos, and Paul Gustavson. Others included Ray Gill, Harold DeLay, Malcolm Kildale, and Tarpé Mills. In relatively short order, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby would work with the loosely affiliated group.

In his The Comic Book Makers, Joe Simon recalled the shop’s location in an office building at 45 West 45th Street, located in a neighborhood that clearly had seen better days. The building itself had “worn, concave marble steps and a dimly lit hall” which led to Funnies, Inc.’s, two-room studio with its generic gray walls. The larger room had a few cubicles off to the side and a large ink-stained table (see p. 32 of Simon’s book).

It was there that the artists who chose to work at the office plied their trade.

Jacquet, for his part, could be found in the second, smaller room, sitting behind an old but clearly cared-for desk. In an interview with Jim Amash for Alter Ego, Joe Simon recalled Jacquet as “a good guy, soft-spoken, with an air of authority about him. He was respectful, and he was respected.” His posture still reflected his military background, as did his carefully polished shoes. He also smoked a pipe. Mickey Spillane, another Funnies, Inc., alum, noted his corn-cob pipe added to his resemblance to General Douglas MacArthur.

Funnies, Inc., continued to produce content for Centaur Comics. Jacquet had managed to leave the employ of Joseph Hardie, “steal” all of his talent, and still remain on relatively good terms with the publisher. That would change, given Hardie’s difficulty in paying Funnies, Inc., for its work. Jacquet’s most successful move for his new shop was his first: obtaining Timely’s Martin Goodman as a customer.

Jacquet’s field man, Frank Torpey, successfully sold Goodman on the idea of using material created by Funnies, Inc., for what became Marvel Comics #1, coverdated Oct. 1939. The precise details of just how that came about are a bit muddy to this day. The important point here is that Bill Everett, doing double duty as

Funnies, Inc.’s, art director, provided the debut of Prince Namor, the Sub-Mariner, Burgos the origin of The Human Torch, and Gustavson the first adventure of the two-fisted Angel.

Funnies, Inc.’s, second success was the launching of Target Comics for a new company named Novelty Press. And, given the conservative instincts of its publisher, it proved to be a rather slow start at that.

Curtis Publishing & The Saturday Evening Post

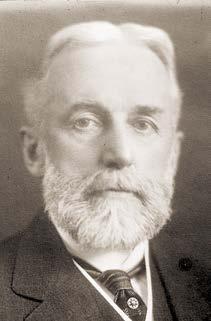

Curtis Publishing, the owner of Novelty Press, had been in the business of putting out magazines almost as long as Street & Smith. Cyrus H.K. Curtis, born in 1850, established himself as a savvy businessman by overseeing the creation of The Ladies’ Home Journal in 1883. A family affair, the Journal was initially edited by his wife Louisa Knapp Curtis. His next notable move was purchasing in 1897 a struggling periodical named The Saturday Evening Post. At the time, the Post had a total of two thousand subscribers. That was soon to change.

In 1903, Ladies’ Home Journal became the first American magazine to reach one million subscribers. By 1917, The Saturday Evening Post passed that same benchmark. Through engaging content, striking cover illustrations, and novel distribution strategies (Curtis distributed its own magazines and utilized an army of juvenile salesmen), the Post became the nation’s most popular weekly magazine. The Country Gentleman, a periodical for farmers purchased in 1911, also took off.

Cyrus Curtis died in 1933 with his publishing empire in splendid shape. The one demographic Curtis had never tried to cultivate was young readers. That all changed with the debut of Jack and Jill in 1938. Its editorial approach is worth examining, as the magazine provided a partial template for the comicbook enterprise that followed.

Jack and Jill featured a mix of fairy tales and more down-to-

4 A Golden Age History Of Novelty Press

Lloyd Jacquet (on extreme right in photo) had, ironically, had been the first editor both of what became the National/DC line of comics in 1935 with his handling of New Fun #1—and of Timely’s first title, Marvel Comics #1, in 1939. Seen in this New Year’s Eve 1940 photo are Timely publisher Martin Goodman (center) and artist Carl Burgos (left). Courtesy of Wendy Everett.

Cyrus H.K. Curtis (in a circa-1918 photo) and his earliest magazine success: The Ladies’ Home Journal (issue shown is dated July 1902). [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

artwork for three installments of “Spacehawk” to prevent any problems being created by Novelty’s rejecting artwork.

In September 1940, in an effort to better explain this new reality to Wolverton, Jacquet advised that the trend in comicbooks was moving towards lighter entertainment: “As you know, the parents and teachers’ associations have given the comic magazines a strong blast against horror stuff, so we have to soft pedal that some way” (Sadowski, Vol. 1, p. 162).

And, in the case of Novelty Press, editors were also very sensitive to the input of their juvenile readers.

An Army Of “Associate Editors”

Just as they had with Jack and Jill, the folks at Curtis/Novelty Press were interested in engaging readers and building their loyalty to the periodical in question. In that spirit, in the first issue of Target Comics, readers were offered coupons which they could collect and redeem for prizes. The coupon idea apparently never quite took off. By the end of 1940, Novelty Press actively solicited letters of comment instead.

With the tenth issue of Target Comics (as would become common practice in all of their publications), the editors at Novelty Press invited readers to become “associate editors,” telling the

powers-that-be what they liked and didn’t like. They sweetened the pot by promising one dollar to every reader whose letter got published. Controlling for inflation, that single dollar would be equivalent to $20 today!

At this point, it is important to note that the address to which readers sent their letters was that of Novelty Press and not Funnies, Inc. In some ways that only made sense, as it was Novelty Press that would have to write the checks. But it also set up another source of “editors” for Funnies, Inc., to please, ones whose preferences could be even more quixotic than those of the publisher.

White Streak’s Rise & Fall

Novelty Press’ new and stricter approach to storytelling was also felt by Carl Burgos. Like Wolverton’s “Spacehawk,” his “White Streak” feature had a certain visceral appeal. It had also become increasingly violent.

White Streak begins using his powers to fatally electrocute enemy agents without remorse—perhaps the latter emotion wasn’t wired into his circuitry. In one particularly violent installment, he kills ten different saboteurs, one or two at a time.

And in Target Comics #8, Burgos introduces Dr. Death, “the most ruthless and elusive war criminal [in] the world.” Dr. Death

9 Blue Bolts & Wonder Boys

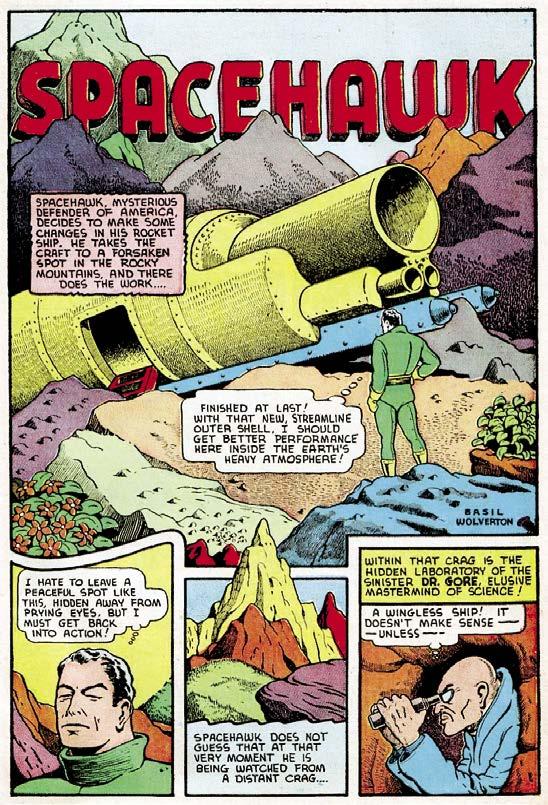

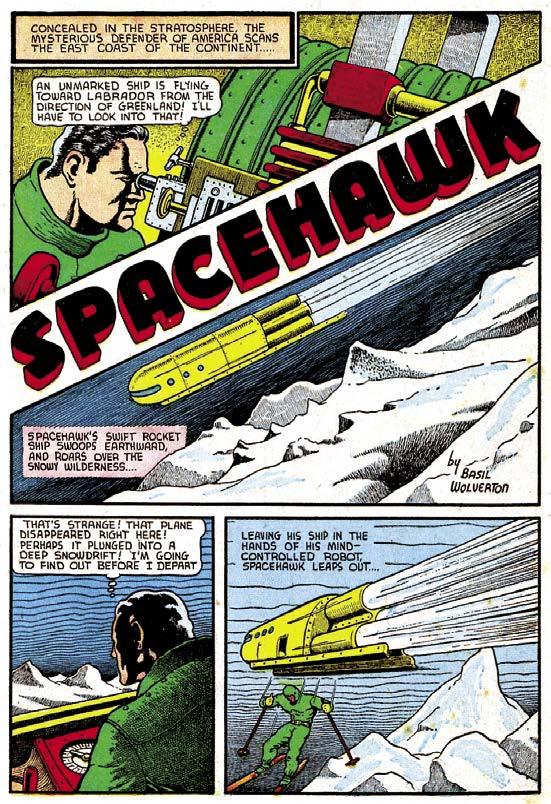

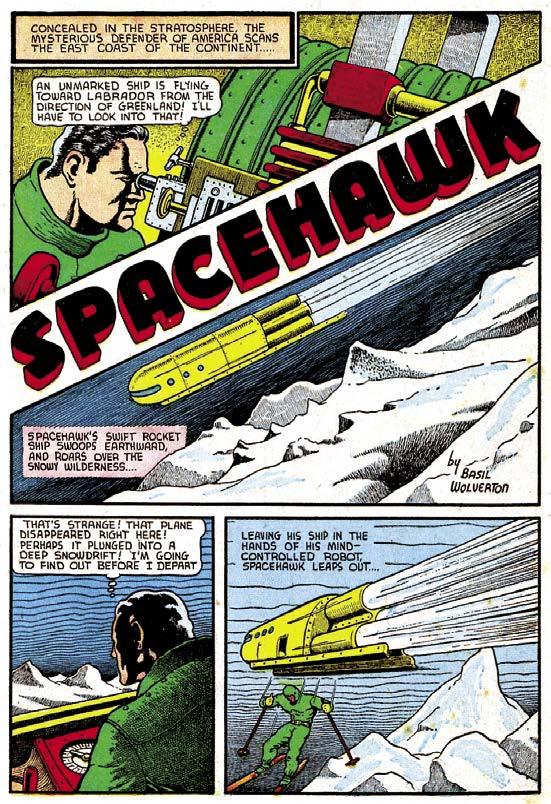

Making A Splash In Space

The exceptional first pages of two of Wolverton’s early “Spacehawk” tales—from Target Comics, Vol. 2, #6 & #7 (Aug. & Sept. 1941). Thanks to Jim Kealy. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

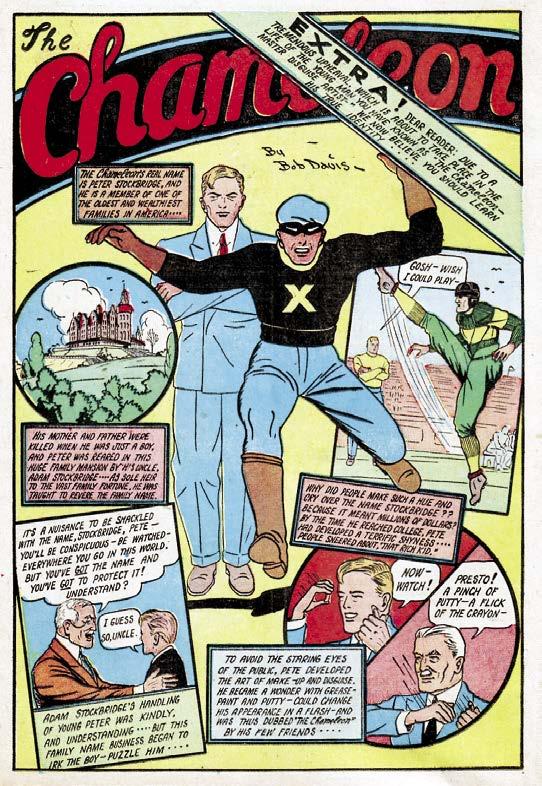

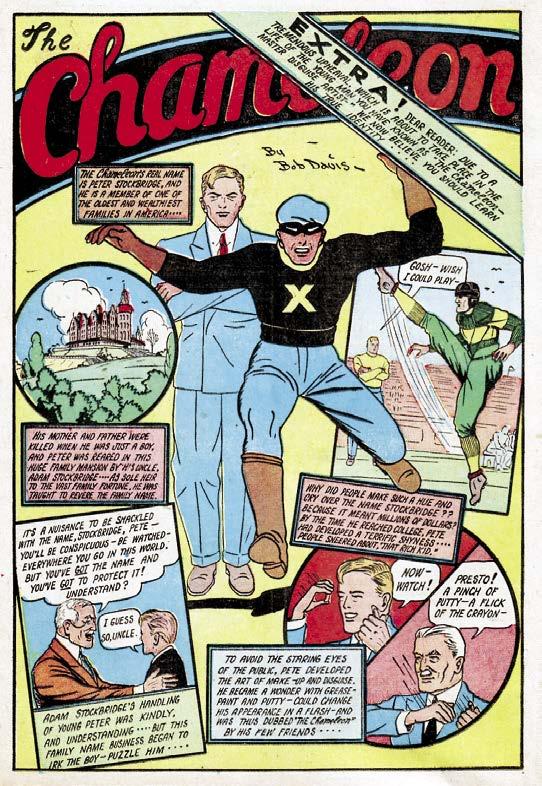

Bob Davis also took over the “Chameleon” feature, quickly making it his own. Davis took the focus off of the hero’s disguises, emphasizing two-fisted action instead. A sinister plastic surgeon fittingly named Dr. Knife was introduced; he turned one of his underlings into a lookalike for our hero. Davis even gave The Chameleon a costume to wear when not in disguise.

One of the “associate editors” disapproved. “That uniform makes him like all the other comicbook characters of his type. It destroys all his originality,” he groused in a letter of comment.

The editors at Novelty Press agreed, and said so in print. Davis dropped the costume after just two issues.

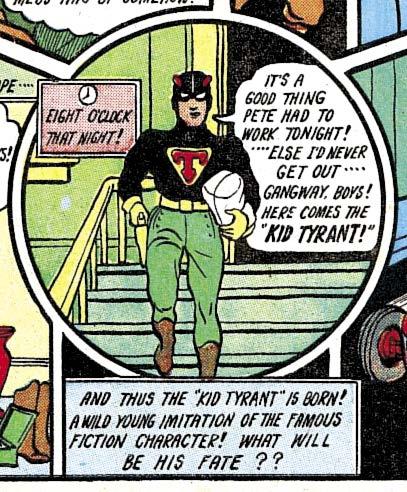

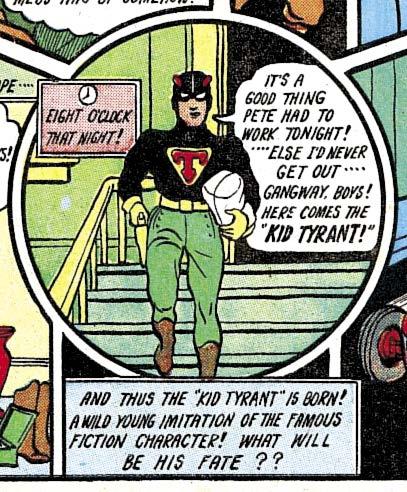

But Davis’ introduction of a feisty orphan named Ragsy stuck. Four issues later, Ragsy appeared in costume as Kid Tyrant, complete with a water pistol that shot out liquid that could burn a bad guy’s eyes. As we have seen, the creators at Funnies, Inc., resisted relinquishing super-hero trappings in their stories to no avail. The Kid Tyrant costume, not to mention alter ego, disappeared just as quickly.

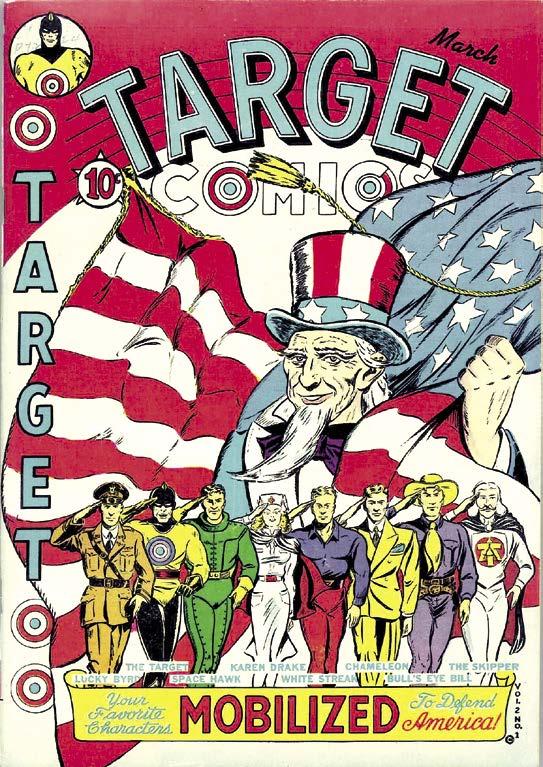

Uncle Sam Comes Calling

Instead of a focus on fantastic costumes and powers, Novelty Press clearly had a new focus in mind.

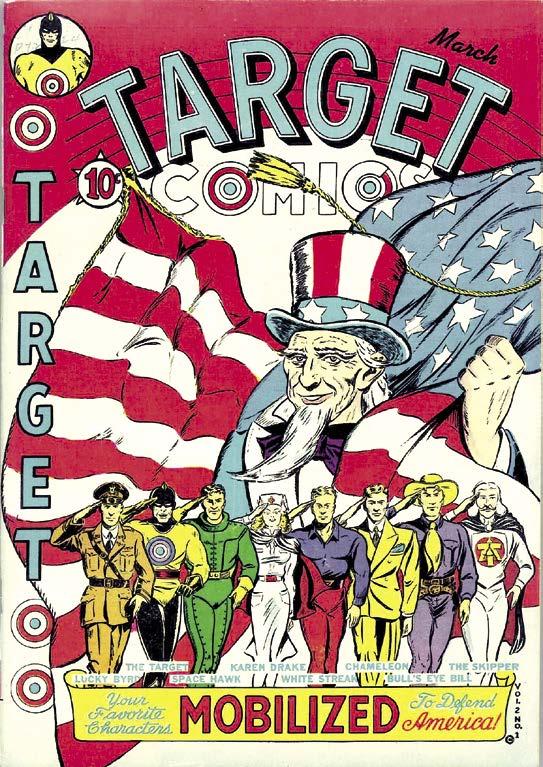

“Attention! Target Comics Characters!” Uncle Sam’s words are huge on the first page of Target’s 13th issue, cover dated March 1941. The dramatic artwork was courtesy of Ben Thompson. Pearl Harbor was still nearly a year down the road, but the publisher clearly felt

Karma Chameleons?

(Left:) Bob Davis introduced a costume for The Chameleon in Blue Bolt, Vol. 2, #7 (Sept. 1941)—but it didn’t last long.

(Right:) Somehow, The Chameleon’s costumed sidekick, the oddly named Kid Tyrant, as drawn by Al Fagaly, lasted longer. Thanks to Mark Carlson-Ghost. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

America needed to prepare for the worst.

Uncle Sam, dressed in his typical red, white, and blue regalia, reads off the role call, as all eight heroes stand dutifully at attention. “Each one of you has some special power or ability. You can use

United We Stand!

In Target Comics, Vol. 2, #1 (March 1941), well in advance of Pearl Harbor, the title’s heroes were “mobilized to defend America.” Cover by Ben Thompson, whose photo can be seen on p. 21. Thanks to Mark Carlson-Ghost & Michael T. Gilbert. Incidentally, this call-to-arms cover has the same date as Timely’s celebrated Captain America Comics #1, on which the Sentinel of Liberty was slugging Adolf Hitler in the jaw! [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

18 A Golden Age History Of Novelty Press

Howling In A Gayle

been Al Fagaly who helped Gill get a job writing the red-haired teen sensation. Fagaly and Archie editor Al Shorten were already friends and collaborators. The two had launched the syndicated comic strip There Oughta Be a Law in 1944, with Shorten as writer and Fagaly as artist. By 1946 both Gill and Fagaly were central to the ever-expanding Archie franchise. Gill became its head writer, according to his brother, while Fagaly drew many of the character’s stories and covers.

As Novelty Press continued to expand their lineup, it would be without the help of many of Funnies, Inc.’s, most reliable talents.

Al Fago’s Funny Business

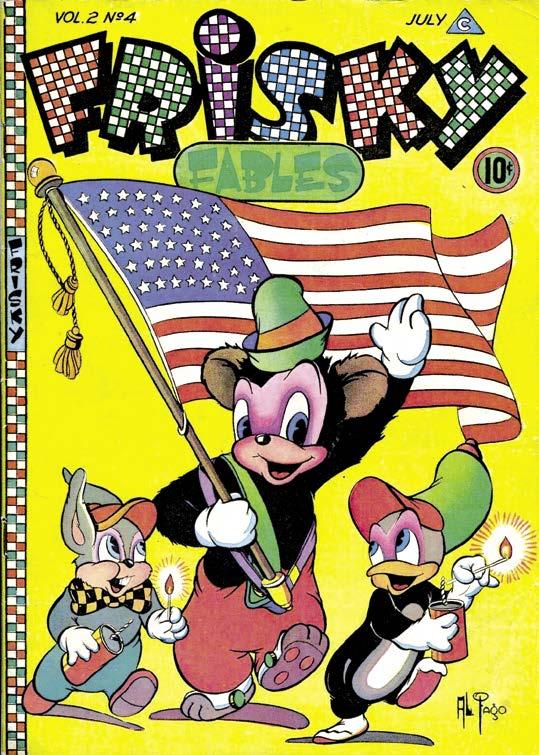

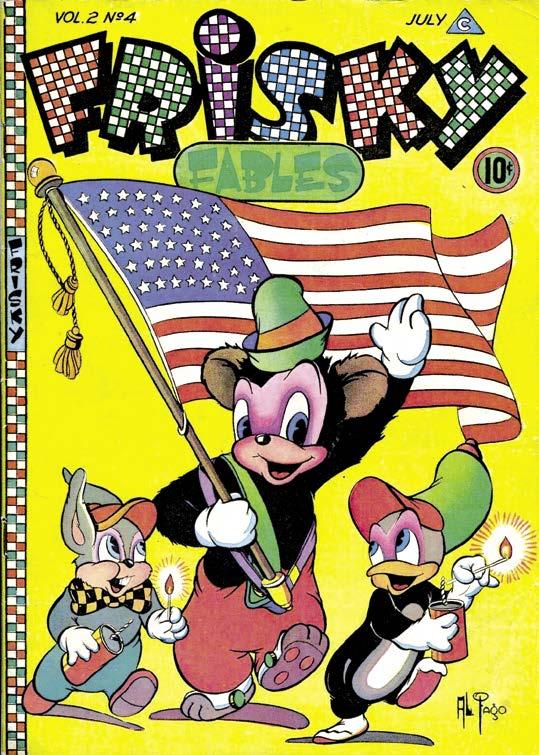

Under Robert Wheeler’s watch, Novelty Press set out to create different tiers of material for juveniles of different ages. For its youngest readers they ordered up a funny-animal comicbook, a genre in which Funnies, Inc., had no experience. Al Fago (not to be confused with the above-mentioned Al Fagaly!) was brought in from the outside to see to the creation of the new title, Frisky Fables

In 1945 Al Fago was just beginning to work in comicbooks. In an Alter Ego interview with Jim Amash, Blanche Fago recalled how her husband had previously “worked for an animation studio

that was owned by The Saturday Evening Post.”

Just which animation studio that was isn’t clear. The likely candidate would seem to be Terrytoons, which was based nearby in New Rochelle. That theory is supported by the fact that Al Fago’s brother, Vince, a funny-animal cartoonist and editor of Timely Comics for two-plus years during World War II, was producing Terrytoon comicbooks for publisher Martin Goodman. Al had even drawn some of the Terrytoon characters there. That said, I haven’t discovered any reference to The Saturday Evening Post having a financial interest in Paul Terry’s operation or any animation company, for that matter. A mystery, at least for now.

The lead feature of Frisky Fables was Al Fago’s own creation, “Neddy the Bear.” When Neddy’s mother finishes telling her son a fairy tale in the feature’s first installment, Neddy replies, “What sentiment, what pathos, what bunk!”

His mother suggests he might try to be a bit more like the

37 Blue Bolts & Wonder Boys

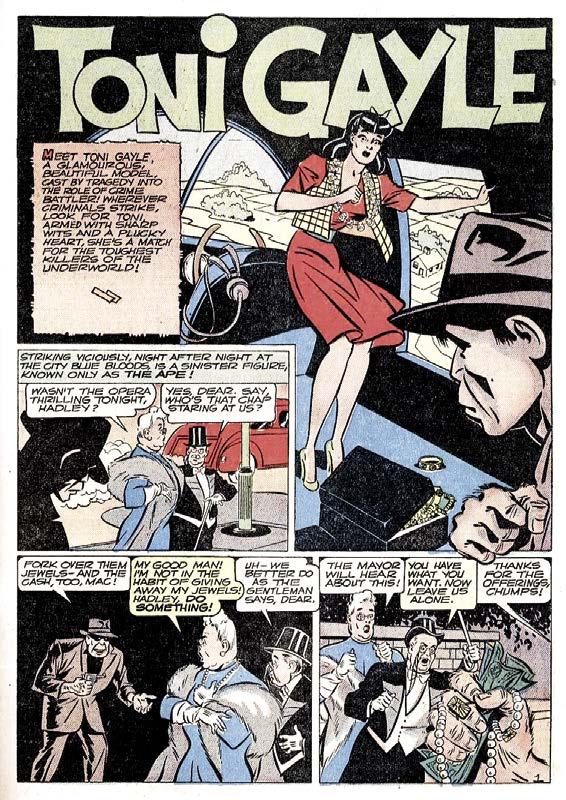

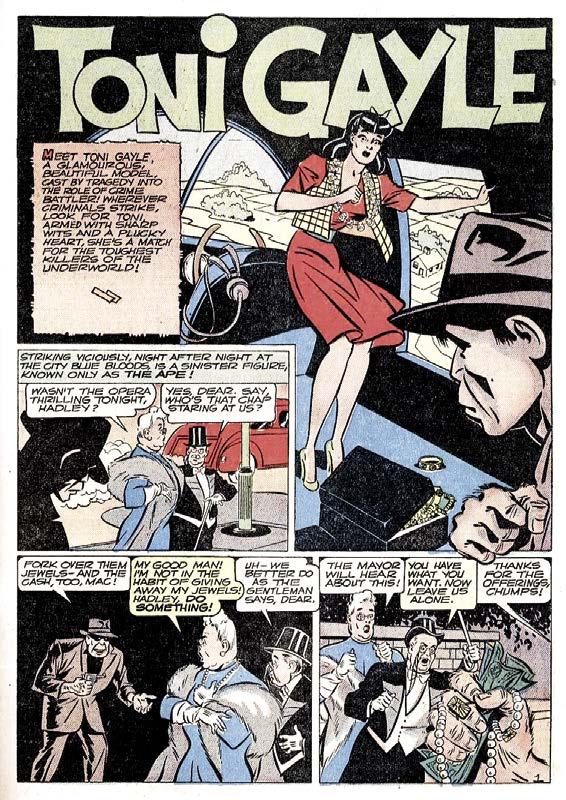

The first issue of Young King Cole also contained the exploits of model-turneddetective Toni Gayle, as penciled by early “Superman” ghost artist Wayne Boring and scripted by Robert Plate. Courtesy of the CBP. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

Wayne Boring

A vintage photo colorized for Eclipse’s Famous Cartoonists cards back in the 1980s.

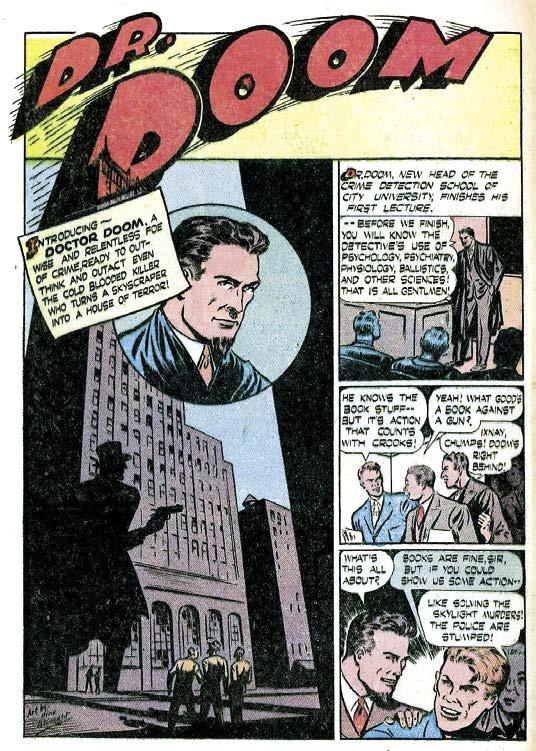

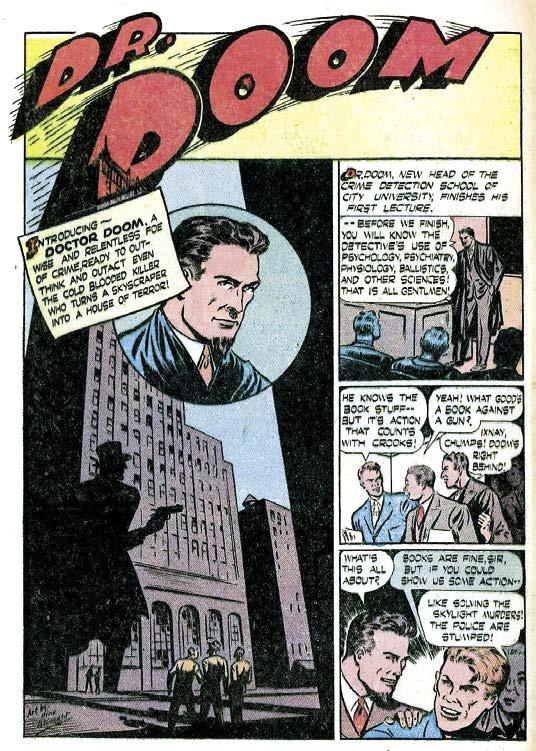

No, Not That Dr. Doom!

The “Dr. Doom” feature was introduced in Young King Cole, Vol. 1, #2 (Nov. 1945), though no writing or drawing credits are known. Thanks to the CBP. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

heroes in those stories. But she also warns him not to venture into the dangerous Black Forest. If ever Neddy is tempted, he is to exclaim. “Get behind thee, Satan!”

Needless to say, Neddy doesn’t follow Mom’s advice and soon regularly encounters fairy-tale figures in the woods. No further references to Satan are made.

Other Fago features in Frisky Fables included “Icicle Ike,” a penguin in New York City attempting to beat the heat, and “Johnny and Woof,” the adventures of a cartoonist and his dog. Fago also utilized work by an art shop named Jason Comic Art or JCA.

By 1946, Al Fago was listed in the indicia of all of Novelty Press’ comicbooks, variously designated as an art editor or art consultant. The role of Funnies, Inc., as the exclusive producer of content was over.

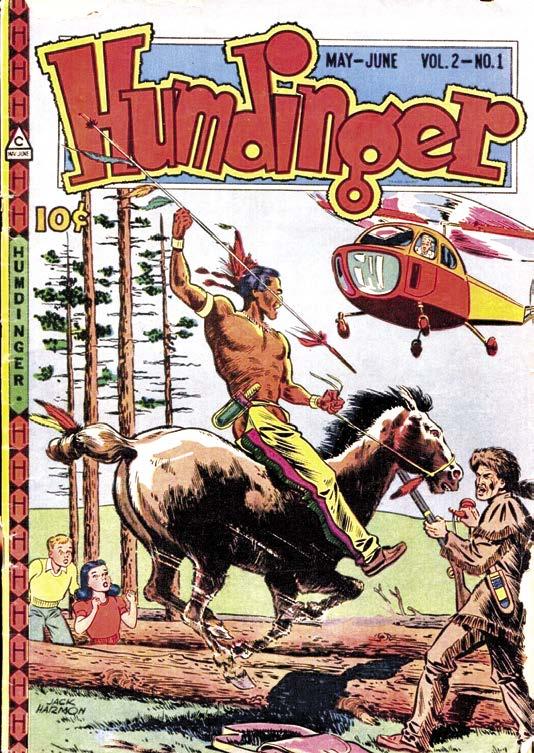

In his new role Fago also oversaw the introduction of a second new humor title. Cover-dated June 1946. Humdinger promoted “Spec, Spot, and Sis” to lead-feature status and introduced a new character named Mickey Starlight. In stories clearly intended to educate as well as entertain, the Hermit of the Woods tells Mickey a new tale of Greek mythology every issue. In addition to joke and game pages, later issues of Humdinger featured “Vic and Ventura in Vacationland.” Their neighbor, a brilliant scientist named Mr. Quiett, took the siblings out on rides on his “secret helicopter,” which was actually a time machine.

Nowhere near as successful as Frisky Fables, Humdinger only lasted eight issues. But Fago would remain in his new quasi-editorial role through 1947. He would later go on to draw “Atomic Mouse” and other humorous features for Charlton Comics and, along with his brother, run a comicbook company, however briefly.

Post-War Adventuring

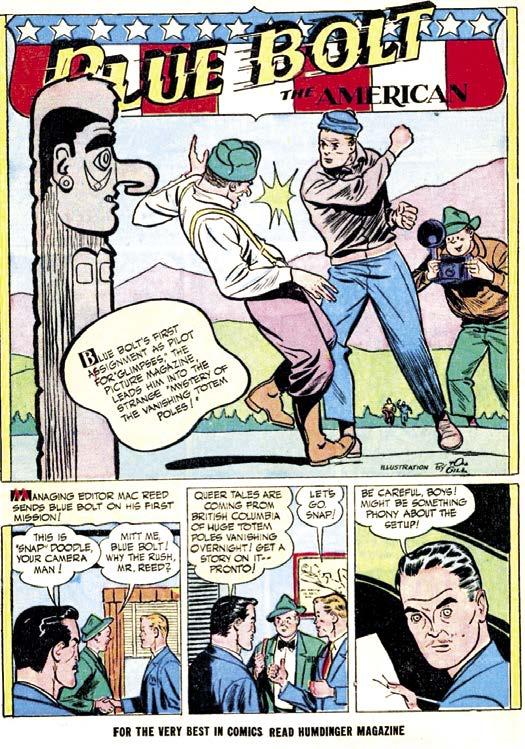

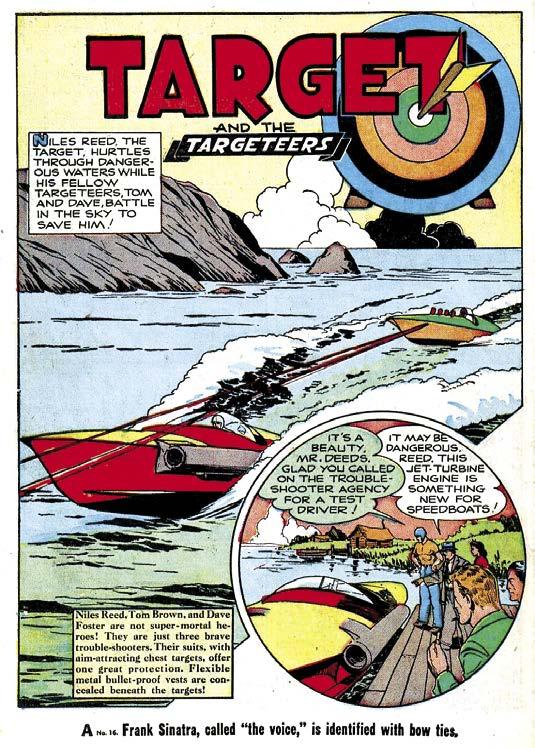

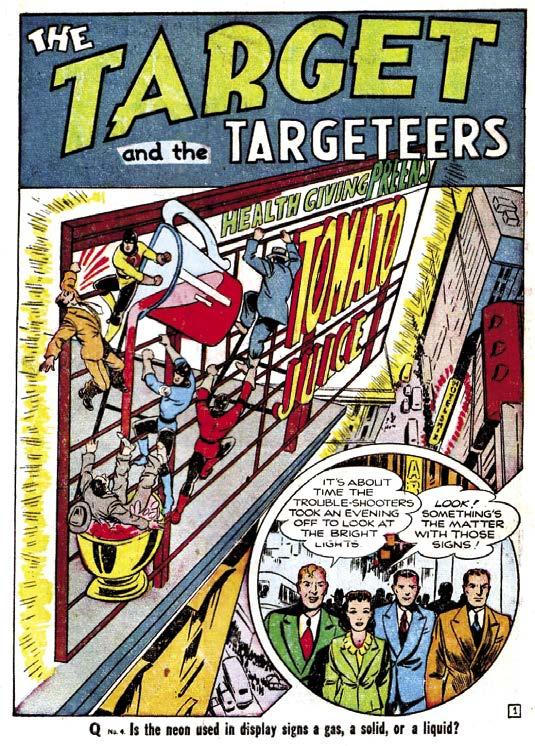

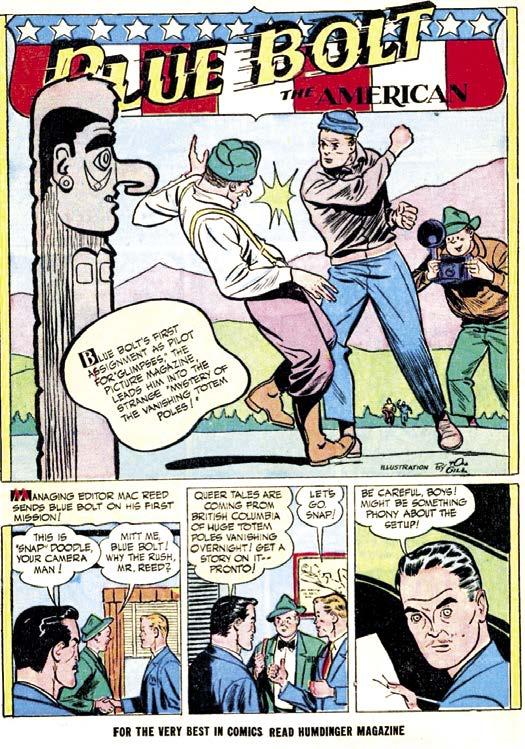

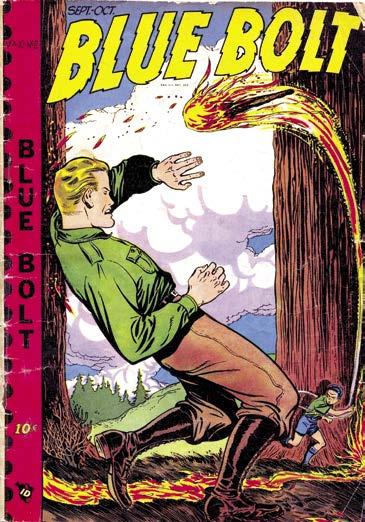

With two comicbooks geared towards younger readers, Blue Bolt and Target Comics once again began to more singularly focus on stories of adventure. Released from military duty, Blue Bolt (his civilian name was never resurrected) becomes a reporter for Glimpses magazine, with Snap Doodle as his new pal and photographer. Blue Bolt also gains a friendly rival and romantic interest, Marge, an attractive strawberry blonde reporter working for Global Picture Syndicate.

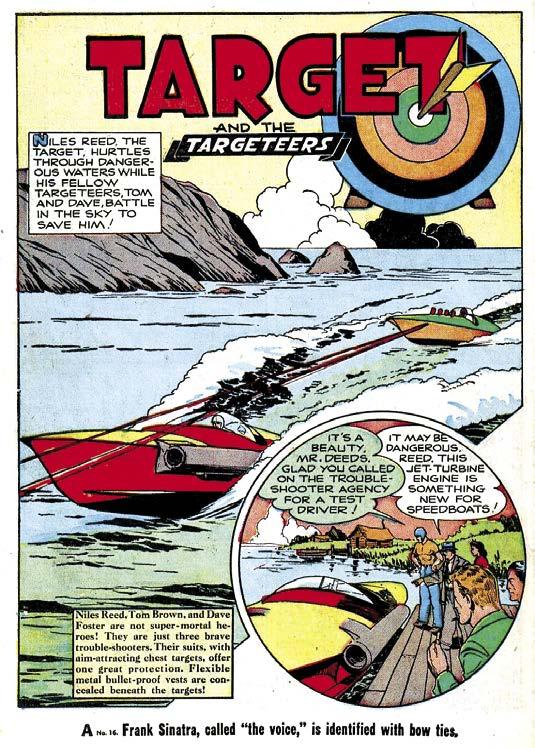

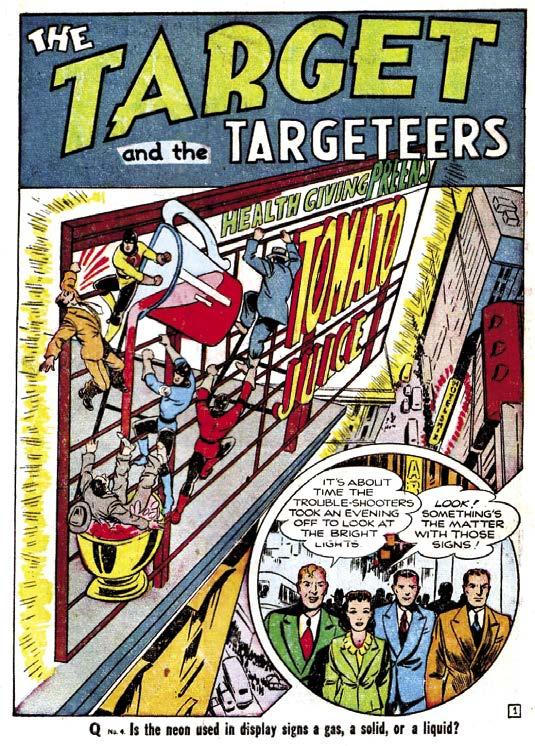

As for The Target and The Targeteers, the trio return home and briefly work for the government as special operatives, enjoying a few globe-spanning missions. Then, released by military intelligence, the three men form The Targeteers’ Trouble-Shooting Agency to serve the public and also make ends meet. Niles remains

38 A Golden Age History Of Novelty Press

Frisky, Yes—Risky, No!

Al Fago’s cover for Novelty’s funny-animal title Frisky Fables, Vol. 2, #4 (a.k.a. #7, July 1946). Courtesy of Mark Carlson-Ghost. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

Al Fago 1950s photo, courtesy of wife Blanche Fago.

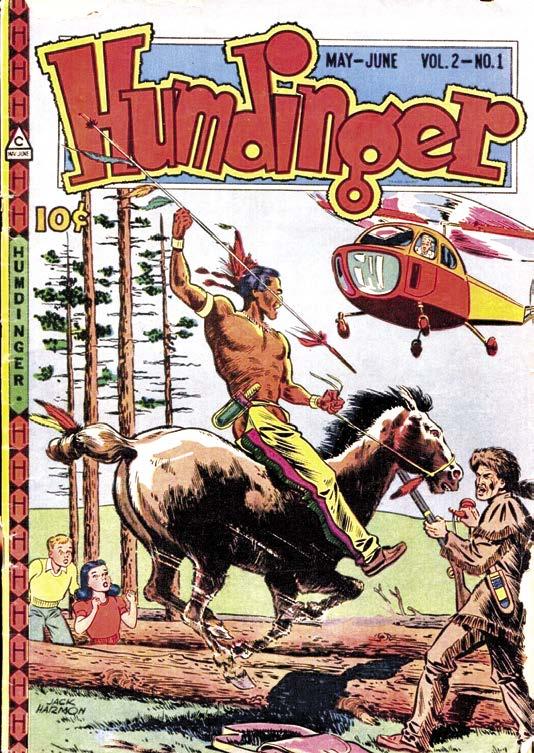

It’s A Real Humdinger!

Novelty’s Humdinger title featured various genres, as seen by this “Jack Harmon” (Wayne Boring) cover for Vol. 2, #1 (a.k.a. #17, May-June 1947). Courtesy of Mark Carlson-Ghost. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

their leader, the men sharing a friendly banter throughout. They also resume wearing their costumes until the end of their recorded adventures in 1949.

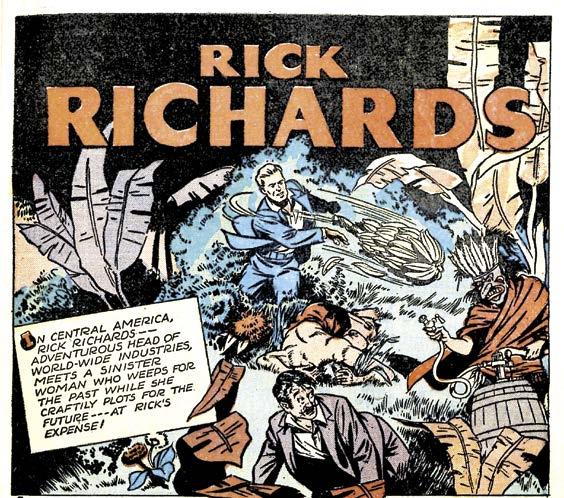

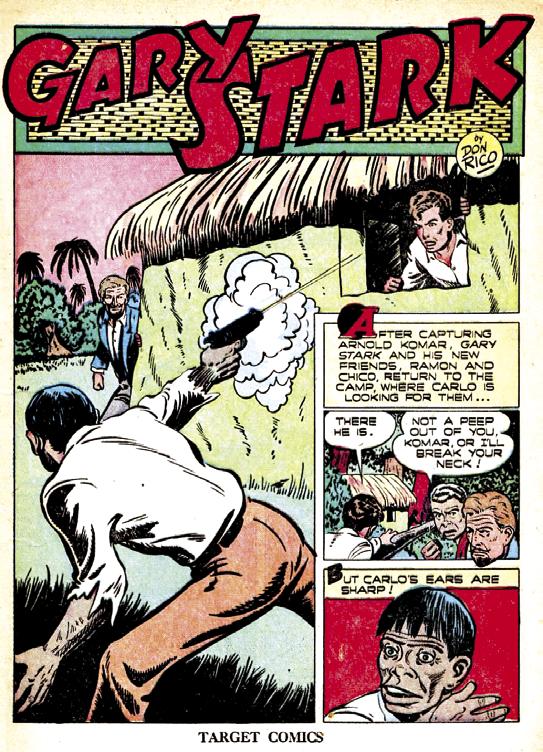

Two new adventure features were also introduced, “Gary Stark” and “Rick Richards.”

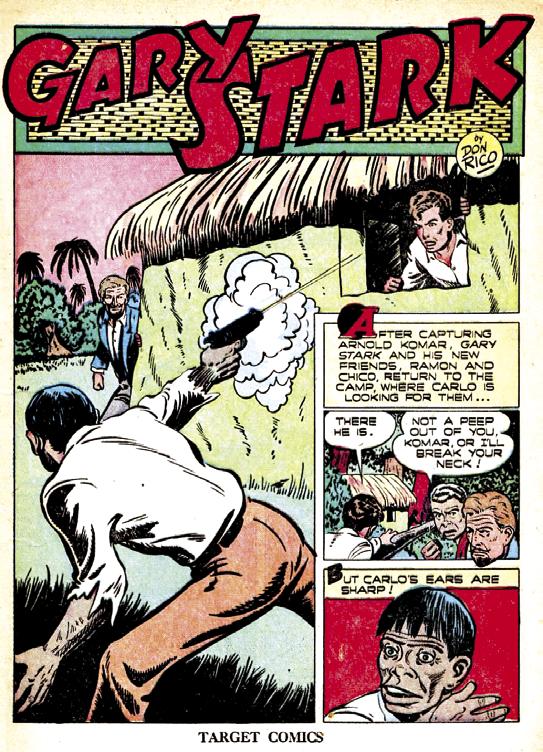

Gary Stark is a handsome brown-haired fellow in his late teens who first appears in Target Comics, Vol. 7, #3 (May ’46), the opening installment of an ongoing serial. Employed as merchant seamen, Gary and his older mentor, Bob Carter, travel around the world in Terry and the Pirates-style adventures. In that spirit, beautiful women naturally abounded—in itself a significant shift in Novelty Press fare.

There’s Panama Condon, a shapely adventurer with a French accent who often finds herself in peril. Lady Jade is a mysterious figure whom thieves seem to fear, a strawberry blonde who talks tough and smokes a cigarette. Zale Storm is a beautiful, dark-haired diamond smuggler. Written and drawn by Don Rico, Stark’s chief adversary is Arnold Komar, “a suave, charming novelist, with one eye on Panama and the other on her wealth.”

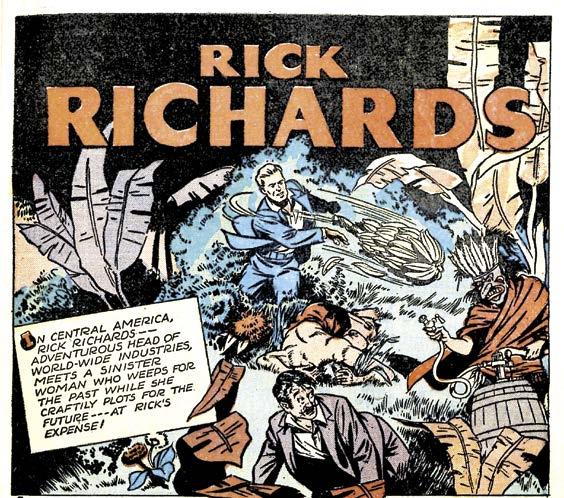

As for Rick Richards, he’s the least super-heroy new super-heroic imaginable. Debuting in Blue Bolt, Vol. 7, #8 (Jan. ’47), Richards is described as a “daring young industrialist,” the head of World-Wide

Postwar Pummeling

After the war, Blue Bolt became a reporter for Glimpses magazine (perhaps a standin for the popular Life?)—while The Target and the Targeteers bounced back and forth between working in and out of costume, as per these splashes from Target Comics, Vol. 9 #1 (March 1948), and Vol. 9, #3 (May ’48). “Blue Bolt” art by Gus Ricca; “Target” art in V9#3 by Ken Battefield; writers and other artists unidentified. Thanks to Jim Kealy and Comic Book

39 Blue Bolts & Wonder Boys

Plus. [© the respective trademark & copyright holders; Blue Bolt name is now a TM of Roy & Dann Thomas.]

Checking In On Lloyd Jacquet

In 1946, after three years in the military, Lloyd Jacquet returned to New York to find his art shop producing a smaller percentage of Novelty Press’ content. All the factors contributing to this aren’t clear. It may be that his wife Grace, while apparently more than competent in many ways, was unable to maintain a kind of boys’ club rapport with Novelty Press that her husband seems to have fostered. All of those lunches he attended may have been accomplishing something after all.

Adventure, Thy Name Is Novelty!

Industries. “Rick takes advantage of his strange physical quirk, result of an old wound—his body floods with adrenal power whenever he hears a loud noise.” An injury sustained during the war gives, Richards’ adrenal spurts that allow him to bend iron bars or tear apart thick ropes. Blond-haired, he favors suits over some outlandish costume.

Exploring his various financial holdings often brings Richards into contact with criminal schemes. He appears to act from the can-do premise that prosperity, scientific advances, and social equality can co-exist and indeed nurture each other. In one story, for example, he spearheads an effort to build pre-fab housing for the poor and butts up against a violent slum lord. Like Gary Stark, Richards remains a fixture until the end of Blue Bolt’s Novelty Press run. The writer behind his stories remains unknown, though his sentiments would likely appeal to art director Mel Cummin. Wayne Boring drew his earliest adventures.

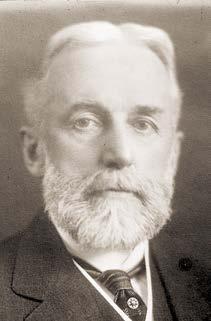

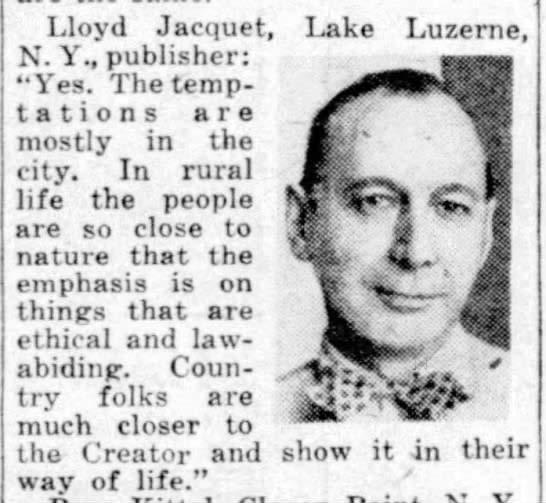

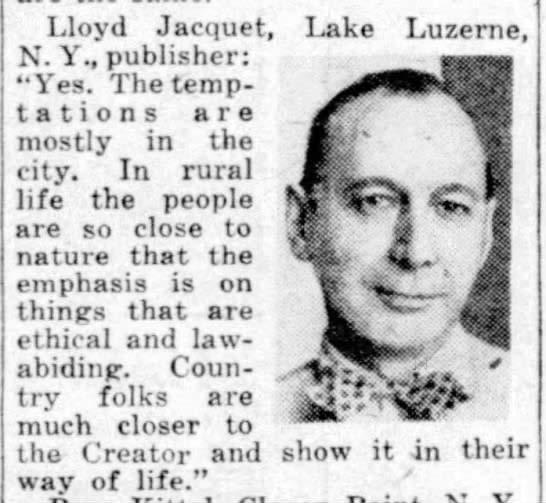

After this, Jacquet’s name largely disappears from oral accounts of the comicbook industry. Luckily for this history, Jacquet’s name can be found in a popular newspaper feature in The New York Daily News called “The Inquiring Fotographer.” Its creator, Jimmy Jemail, would solicit interesting discussion questions from readers and then ask a small group of contributors to provide their response to it. The “fotographer” part of the title was because Jemail would always include a photograph of the folks offering up their thoughts. Jacquet was one of the column’s occasional contributors.

The two available columns with Jacquet’s thoughts offer some valuable insights into his belief system. As will be seen, it was very much in sync with that of the editors of Novelty Press.

In an August 5th column in 1947, Jacquet gives his profession as “engineer” but his address as “W. 45th St.”—the location of Funnies, Inc. The question on that occasion, given the long shadow cast by Rosie the Riveter and her real-life sisters, was: “Do women need protection today?”

Jacquet’s answer was no.

“Women are well able to take care of themselves,” he opined, “particularly in great emergencies. That was well-demonstrated in Europe during the past war by the underground forces, and in this country by the manner in which women pitched in

40 A Golden Age History Of Novelty Press

The relatively mundane exploits of Gary Stark and Rick Richards didn’t always take place in jungles, but they did in Target Comics, Vol. 8, #10 (a.k.a. #88, Dec. 1947) and Blue Bolt Vol. 7, #9 (Feb. ’47). As drawn respectively by Don Rico and Wayne Boring. Scripters unknown. Courtesy of CBP and Mark CarlsonGhost. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

“The Temptations Are Mostly In The City”

Lloyd Jacquet’s photo appeared with some comments and opinions in a newspaper column in 1947. Courtesy of Mark Carlson-Ghost. [© the respective copyright holders.]

and took the places of men in service.”

The accompanying photo displayed a thoughtful Jacquet, sporting a jaunty-patterned bowtie.

In a January 18th, 1948, installment of the feature, Jacquet addressed the question “Do you agree with Oscar Wilde that ‘Anyone can live in the country: there are no temptations there’?”

“Yes,” Jacquet argued. “The temptations are mostly in the city. In rural life the people are so close to nature that the emphasis is on things that are ethical and law-abiding. Country folks are much closer to the Creator and show it in their way of life.”

Jacquet’s reply is reminiscent of his counsel to George Mandel, seemingly ensnared by some of those big city temptations. Identifying his profession as publisher on this occasion, he notes his residence as Lake Luzerne, a picturesque community in upstate New York, hours away from Manhattan. As if often the case, these scattered facts, lacking in context, raise more questions than they settle.

What is known is that the influence of Jacquet on the goings on at Novelty Press were clearly waning. And the arrival of one L.B. Cole only sped up the process.

Enter L .B . Cole

One of the interesting aspects of the post-War Novelty Press comicbooks was their look. While the quality of their artwork was still variable, the comic pages looked particularly clean, clear of clutter.

“The printing in this magazine is large and clear,” the editors boasted in a letters page, adding that all Novelty Press comicbooks “have large, clear, easy-to-read type. There are fewer words and fewer pictures in these magazines than in many others, but they are easy on the eyes. Do you vote for that?”

By “fewer pictures” it appears the piece meant fewer panels, now never more than six.

The woman behind the lettering of this post-War era was the wife of L.B. Cole. Utilizing the Ames tool for lettering, Cole bragged that his wife Ellen “became one of the top three letterers in the industry. Everybody wanted her to work for them….” (Boatner, A-59).

It appears Ellen Cole began working for Novelty Press around 1945. According to her husband, she was influential in getting him freelance work for them in 1948. It doesn’t appear that Cole worked through Jacquet’s shop.

Cole’s influence was immediate and significant. He began

Carrying Cole To New Castles

providing colorful and visually striking covers at precisely the time several new and significant changes were happening in the company’s line of titles. It’s easy to wonder if Cole may even have influenced them, even though Wheeler and Cummin are still listed as the editorial powers in charge.

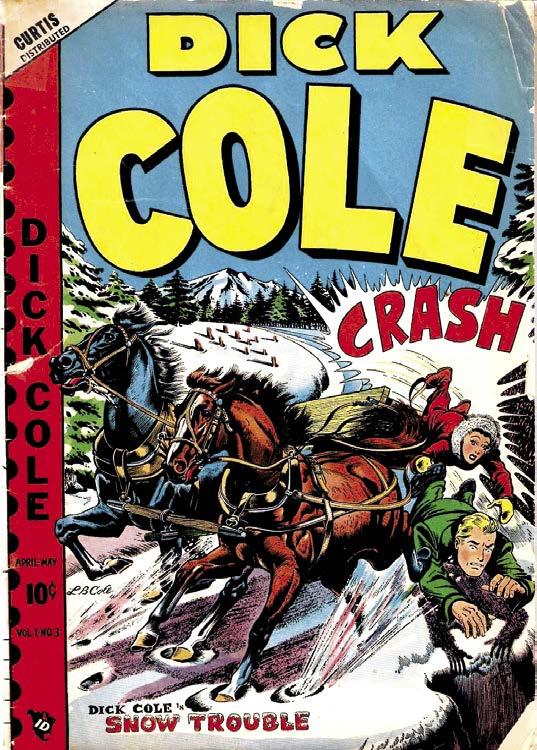

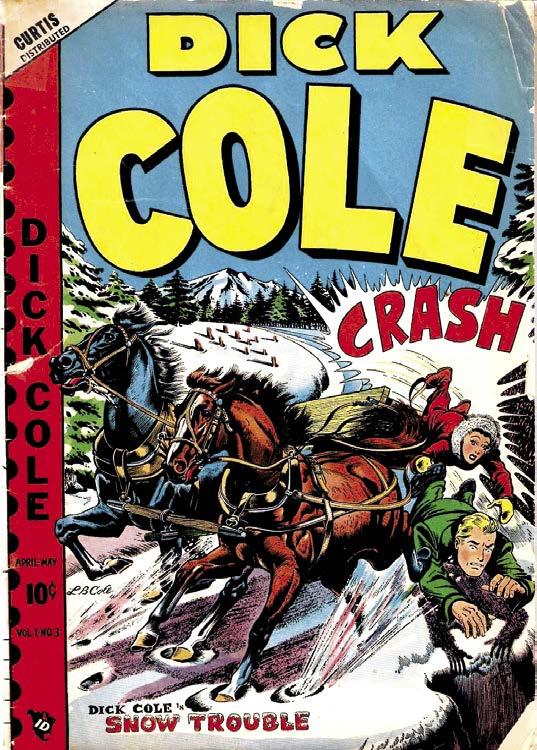

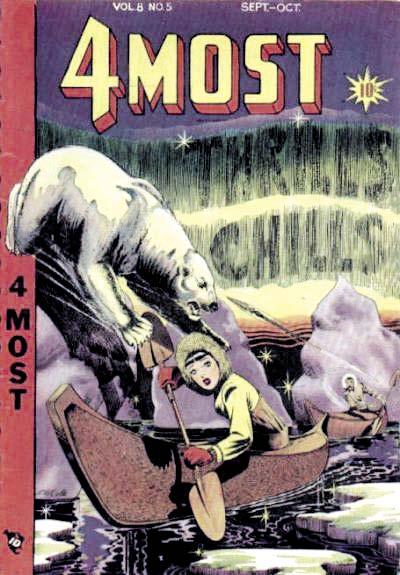

The first change was that Dick Cole was finally awarded his own comicbook. Given his popularity, it was a logical choice. The Cadet took over his cover spot at 4Most

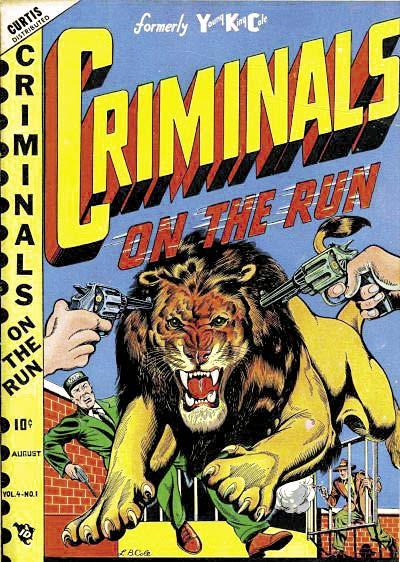

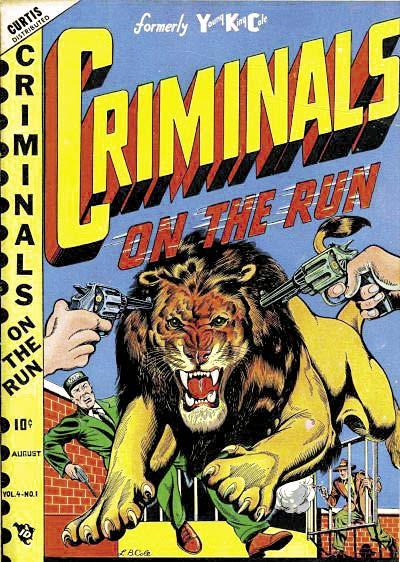

The more sedate-sounding Young King Cole Detective Cases became Criminals on the Run, a shift in title unimaginable even two years before. The contents remained largely the same as before, though now a true-crime story was added to the mix. The editors attempted to reassure the reader, and perhaps his/her parents, that the change was only made so that “people who have never read this magazine can look at the title and get a better idea of the kind of stories inside….”

Criminals would never be glorified. It was “criminals on the run,” they declared.

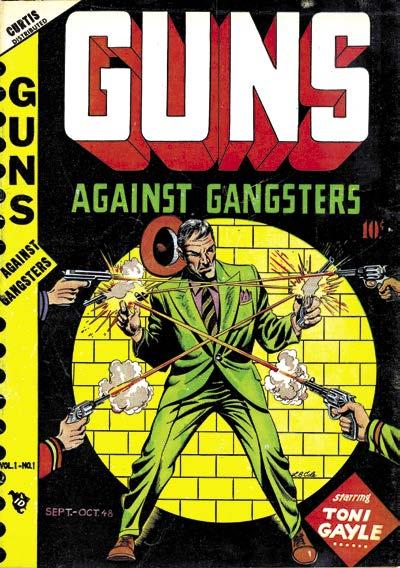

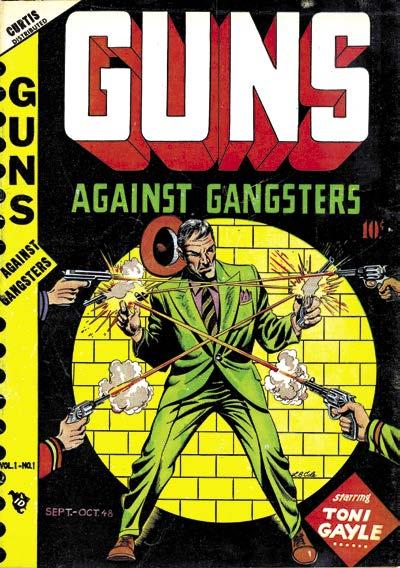

Whatever their claims, the publisher clearly desired to capitalize on the success of Crime Does Not Pay. A second crime title was added, Guns against Gangsters. The popular “Toni Gayle” feature was moved to the new book, as well as stories devoted to Toni’s father, Gregory Gayle, now known as “Gunmaster.” As his name suggested, Gayle was an excellent shot and an expert on firearms in general.

In the launch of that new title, the editors continued to sound defensive.

his strong design sense.

Dick Cole was a belated attempt by Novelty (now sporting a “Curtis Publishing” sigil) to devote an entire comic to its most popular character ever, but the solo title lasted only six issues.

41 Blue Bolts & Wonder Boys

(Left to right:) One-time comicbook letterer Ellen Cole (years later, in the mid-1970s)— husband Lester (“L.B.”) Cole in 1944—and L.B.’s cover for Dick Cole, Vol. 1, #3 (May 1949), which showed his mastery of the drawing of animals, along with

Cover courtesy of CBP. [Cover TM & © the respective trademark & copyright owners.]

“Read about the Gunmaster’s perils and escapes. Learn about guns—and how they are used in the fight against crime. It’s guns against gangsters, you know—guns in the right hands—guns used only at the right time.”

In the meantime, Toni Gayle proved popular enough with readers that editors decided to add her to the 4Most anthology of Novelty Press’ top features. In addition to doing nearly all of the company’s covers, Cole also began drawing her stories there.

The parent company of Curtis now signed off on including a prominent triangle in the upper right-hand corner of every cover stating “Curtis Distributed.” It wasn’t just parents that Novelty Press worried about. It was also what comicbooks newsstands would be willing to include in already overcrowded comic sections. Novelty Press also began to have a distinctive strip run along the left side of their covers to identify the comicbook as theirs when stacked back-to-back.

All of these changes have the earmarks of L.B. Cole’s savvy marketing instincts. How many were actually his ideas remains unclear, only that they closely coincided with his arrival.

Novelty Press Closes Up Shop

Despite the effort of editors to thread the needle of how their crime stories were more wholesome than others, the shift in focus came at a bad time. The significant increase in crimeoriented titles on newsstands prompted a new wave of public criticism. In late 1940s, it was concern over the violence of crime comicbooks that fueled the uproar.

The other reality was that post-War sales numbers were nowhere near as good as they had been. Average paid sales for Novelty Press titles in 1948 were just under 200,000, a marked decrease.

Increasing controversy over the contents of comicbooks and diminishing financial returns made the decision to abandon ship a relatively easy one. The final issues of the Novelty Press’ remaining comicbooks were cover-dated September or October 1949.

In the final issue of Novelty Press’ Blue Bolt, the editors voiced their uplifting thoughts as usual, discussing the questions of “What makes Americans such ‘all-around’ people?” and “What makes

42 A Golden Age History Of Novelty Press

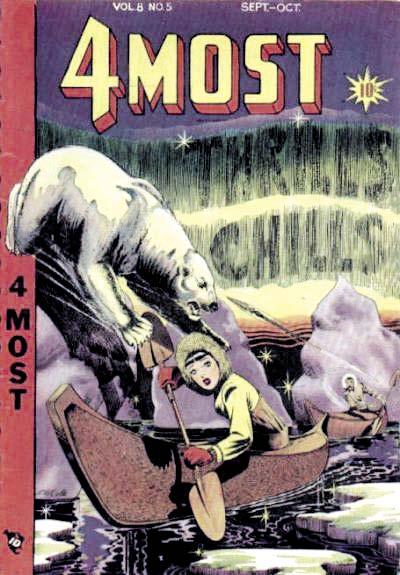

When The Novelty Wears Off

The covers of the final issues of 4Most (Vol. 8, #5, a.k.a. #36, Sept.-Oct. ’49) and Blue Bolt (Vol. 10, #2, a.k.a. #101, Sept.-Oct. ’49). The first is the work of L.B. Cole, the latter of Jim Wilcox. The final Target Comics cover appeared way back on p. 3. Courtesy of the GCD. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

Crime Comes To Curtis—Big-Time!

L.B. Cole provided the cover art for Novelty’s Criminals on the Run, Vol. 4, #1 (Sept. 1948) and Guns against Gangsters, Vol. 1, #1 (Sept.-Oct. ’48). Criminals on the Run itself had evolved just one issue earlier from Young King Cole. Thanks to CBP. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright owners.]

And Back Again!

Harvey Romance Comics— Before & After The Comics Code

by John Benson

Of the many little-known oddball byways to be found in the newsstand comics of the 1950s, the Harvey romance line after the implementation of the Comics Code Authority stands out.

When the Code was created at the end of 1954 and the comics industry suffered a collapse, the Harvey brothers continued their romance titles, but turned to a policy of reprints. (The reduced costs of this policy offset the presumably smaller Code-era circulation.) The changes that were made to the stories to sanitize the line sometimes produced bizarre results. To understand why these changes were so strange, it’s helpful to know the mechanics of the reprinting process.

The Harveys had saved both the original art and the printing plates; thus, reprinting, even with the necessary Code changes, was very economical. Changes were made right on the original art, and new black plates were made. But the original color plates were reused, which meant that all the labor-intensive and costly stages of coloring a comic could be eliminated, from doing the mechanical separations to making new plates. Reusing the same color plates, however, imposed some significant limitations.

The Harvey 32-page comics were printed as a single signature on giant web presses. For each color there were eight flats made up of four pages each, each flat resulting in a plate. (This is logical when you realize that these presses were designed to print Sunday newspaper comics: Four comics pages are equivalent to a full newspaper page.) So there were a total of 32 plates per issue, eight for each of the three colors, plus eight for black. At a certain point Harvey comics developed a standard format of five-page stories, so that ad pages came together on the same plates. This was originally done so that a block of ad pages could be prepared once and then used for different titles coming out at the same time, since ads were sold on a “block” basis for multiple titles. Flats 1, 2, and 8 were reserved for the following items: ads, texts, one-page comics stories or features, and the first page of the comic, which was used for a contents page. Flat 1 consisted of pages 1, 16, 17, and 32; flat 2 consisted of pages 2, 15, 18, and 31; and flat 8 consisted of pages 8, 9, 24, and 25. What’s left are five flats that, collectively, represent pages 3-7, 10-14, 19-23, and 26-30. The four five-page stories of the issue were spread over these remaining five four-page flats. Significantly, each flat contains pages from all four of the stories in the issue.

Although originally designed to make it easy to put blocks of ads in different titles, this format worked out very well when it came to reprinting the comics with the same plates. New flats and plates could be made up for flats 1, 2, and 8, with new ads; they could even run more ads than before, by replacing the one-page features with ads. The remaining flats containing the five-page stories could remain unchanged, using the original color plates. But this process imposed two significant limitations:

First, since the four stories were spread out over the remaining plates, it was only possible to reprint complete issues. This meant that, if they had an issue with

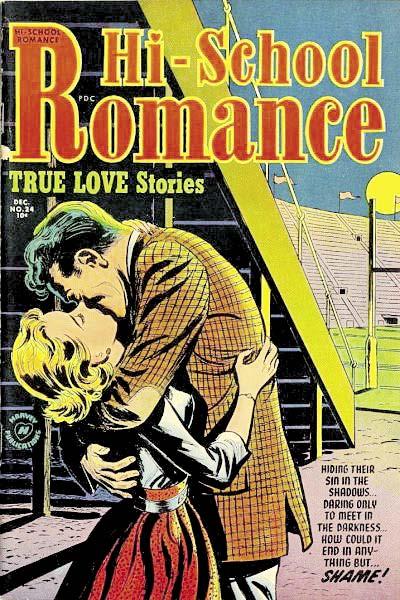

“You Must Remember This… A Kiss Is Just A Kiss…”

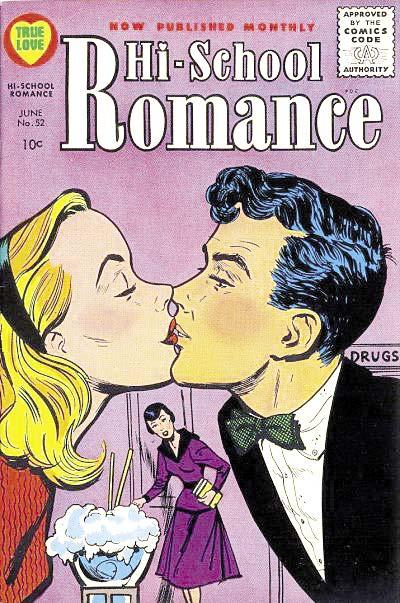

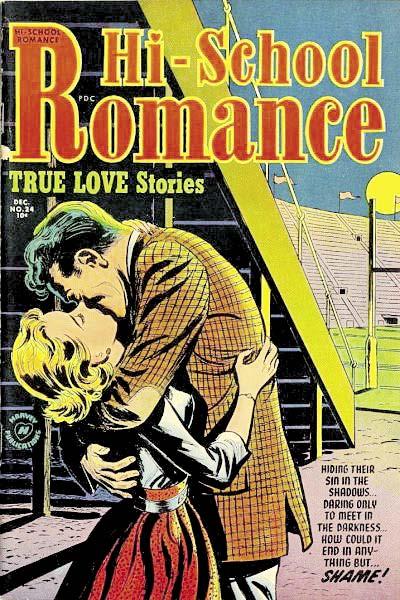

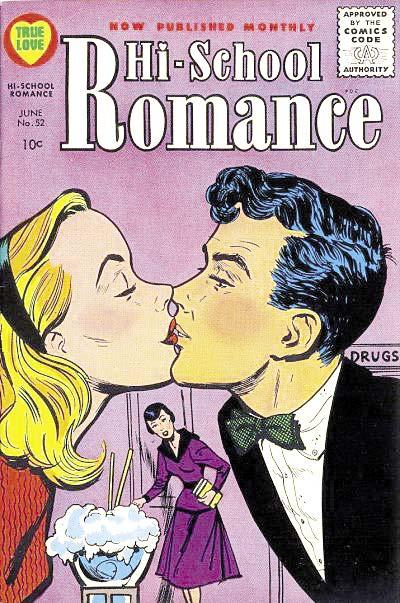

But the post-1954 Comics Code had a far different idea of what a proper kiss was than the Harvey Comics editors and artists had had a few years earlier! Even when some of the interior contents of pre- and postCode issues might be basically the same stories, new covers were called for, in order to protect the (young) public’s morals. (Top:) Now that’s a smooch, from the cover of Hi-School Romance #24 (Dec. 1953)! (Above:) A light touch of the lips kept Code administrators Judge Murphy and/or Mrs. Guy Percy Trulock happy on that of Hi-School Romance #52 (June ’56). Both covers by Al Avison. Thanks to the Grand Comics Database. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

48

three mild stories and one that required lots of changes, they either had to drop the issue entirely or make the necessary major changes to the offending story. Since Harvey eventually published nearly as many Code-era reprint issues as pre-Code ones, there was pressure to reuse as many issues as possible. Consequently, some stories that were unsuited to reprinting under the Code, and which would never have been reprinted if the folks at Harvey could have picked and chosen individual stories, underwent some bizarre changes to satisfy the Code.

The second limitation that using the same color plates imposed was perhaps even more significant, and was responsible for some of the more amusing changes. The changes were made right on the original art, and new black plates were made as necessary. But these changes had to match the existing color plates. Actually, in some of the earlier Code issues, Harvey ignored this problem. Realizing that the Code only saw the black-&-white corrections, they left the color plates unchanged. The resulting mismatch between the new drawings and the old color sometimes produced strange results. Either the Code caught up with this, or, more likely, the Harveys decided it looked too unprofessional, so in most issues various techniques were employed so that the changed black-&-white images were in conformity with the color plates.

For example, solid black could be added to the art, covering up the area where the original color would now be inappropriate. This was the easiest solution, since it required no change to the color plates. Another possibility was to make a new, different drawing that would fit the existing color, and this resulted in some ingenious changes. Finally, if necessary, color could be removed by routing (gouging) out portions of the plates. When all else failed, a completely new drawing could be substituted for the offending panel and that panel routed out completely on all the color plates, leaving a black-&white panel. But what could not be done was adding or changing the color on the existing plates.

Earlier Harvey issues were not laid out in the standard five-page-story format described above, which caused problems when reprinting with the same plates. For example, First Love Illustrated #84 was reprinted from Hi-School Romance #8, an early issue with the contents page on the inside cover and the first story starting on interior page 1. For the reprint, page 1 became a new combination of contents listing on the top third of the page, and the bottom part of the page a summary of the first two pages of the first story. Page 2 was an ad. Thus the first story was condensed by 1 1/3 pages.

Another story, a three-pager, ended on page 15, a page on the ad flat. The solution here was just to drop the last page of the story and replace it with an ad, leaving the heroine right in the middle of an embarrassing moment, with no explanation.

Nearly all the Harvey Code-era romance stories have changes. This is in marked contrast to the Code-era St. John Publishing romance comics, which were also all reprints but which had virtually no Code changes at all. Of course, St. John only issued about twenty Code-era issues, so they could choose their mildest stories for reprinting. Still, there are so many changes in the Harvey comics that I wondered if they weren’t simply changing things in advance of sending the books to the Code to save time. Artist/writer Ken Selig confirms that they did indeed make changes before the Code reviewed the books.

But Selig says that this was at the direction of Leon Harvey, who had decided, after the outcry and general bad publicity comics had received at the time, that the Harvey comics must henceforth be “tasteful” and completely innocuous. Selig started with Harvey Publications in 1954, just as the Code was starting up, and was the one who made the changes on the Code issues, reducing the size of “the busts on the good ladies” and making a host of other changes. Selig personally thought that the horror comics were terrible and the romance comics were far too sexy and blatant, and so he needed no encouragement to make the books innocuous. According to Selig and Sid Jacobson, Joe Simon was “editor” of the Harvey romance books during the Code era, so it was presumably Simon who rewrote the captions and balloons, or at least oversaw

49 From “Shame” To “Sham”—And Back Again!

“Goodbye,

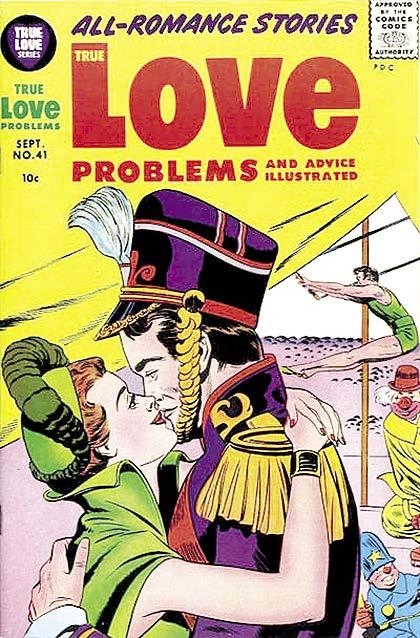

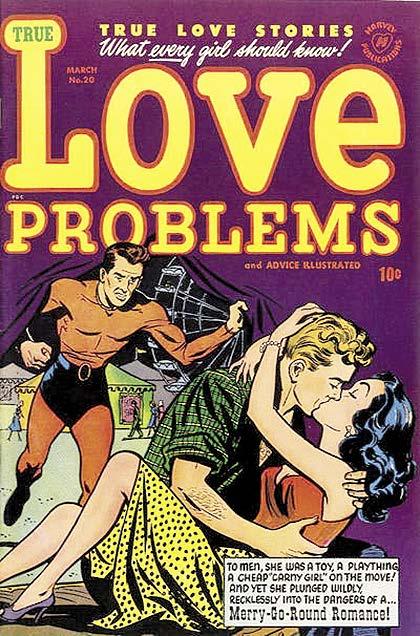

Cruel World—I’m Off To Join The Circus!”

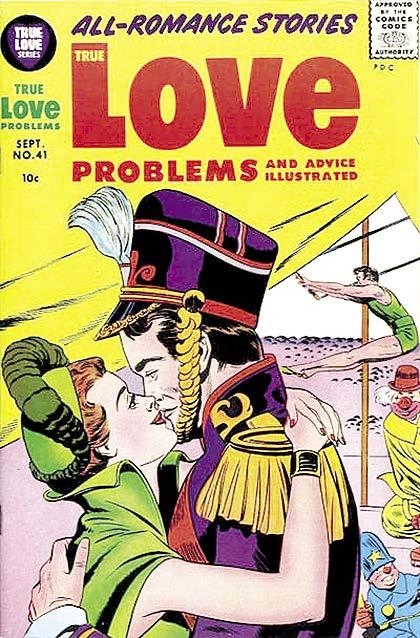

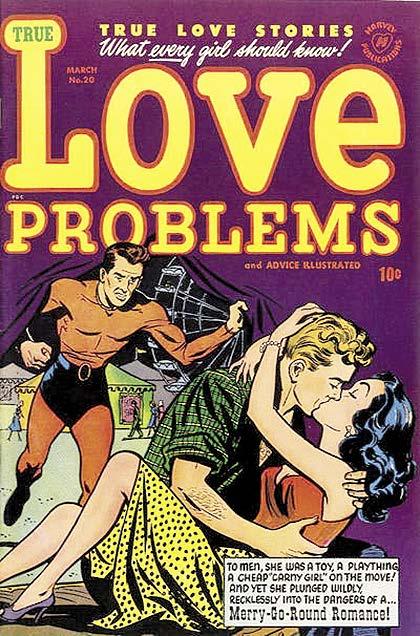

The angry acrobat on the cover of True Love Problems and Advice Illustrated #20 (March 1953—artist unknown) looks like he might do some serious damage to his two-timing girlfriend and her paramour—but when that story was reprinted and a new cover done for issue #41 (Sept. ’56), the Harvey folks got Jack Kirby to draw a far more light-hearted one. And this from the artist who, along with then-partner Joe Simon, had invented love comics! Thanks to the GCD. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

55

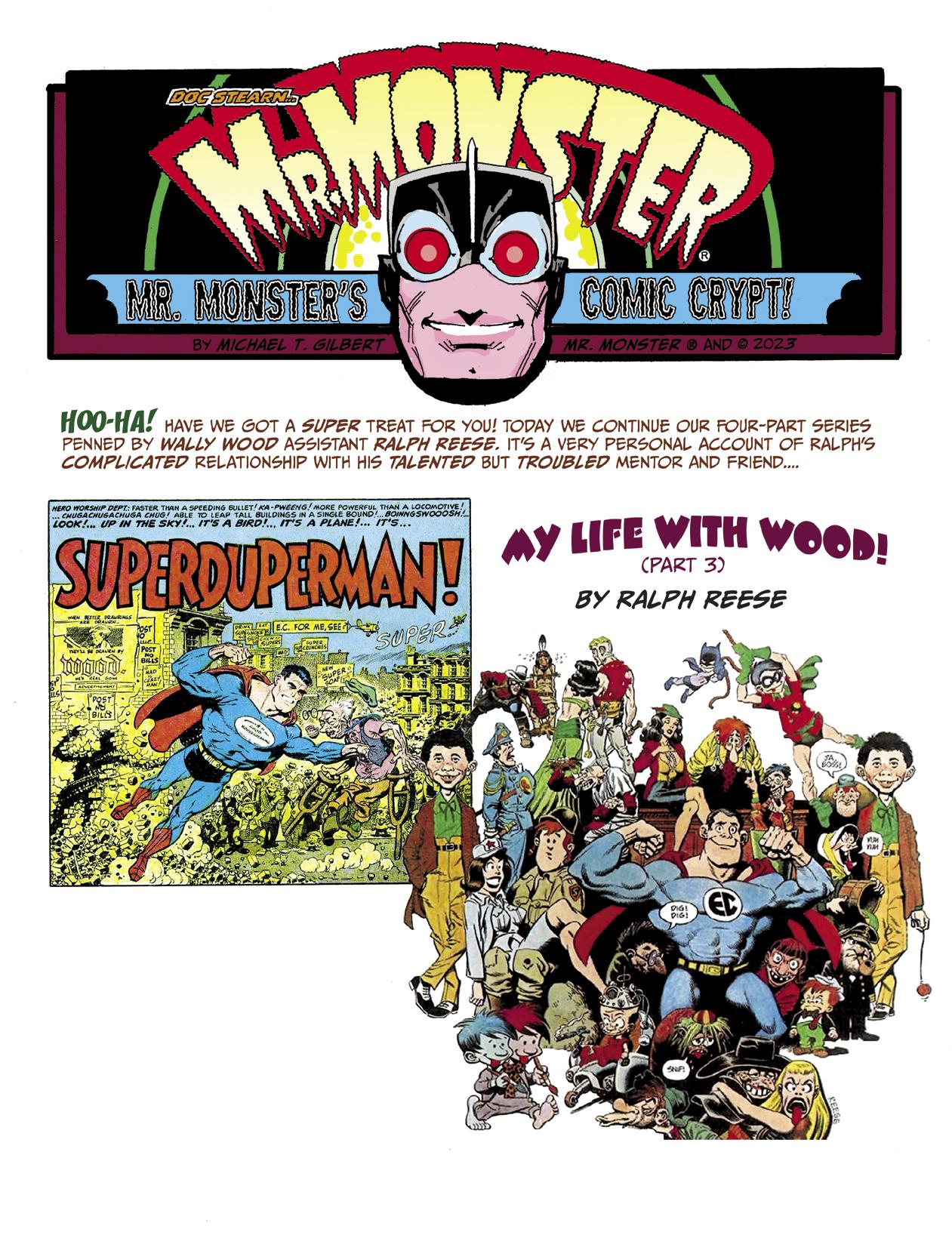

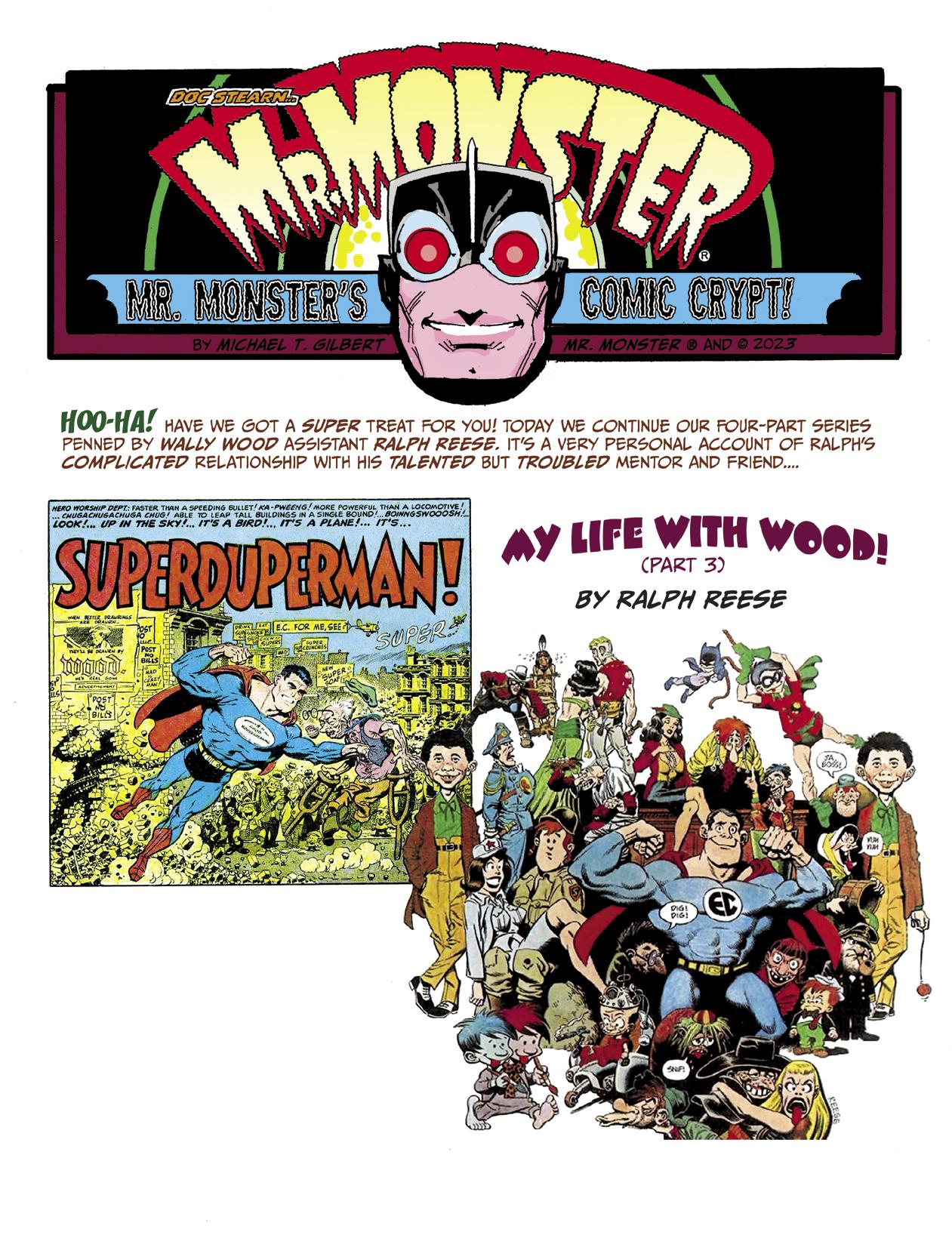

(Above:) Mad #4 (April 1953) featured Kurtzman and Wood’s classic “Superduperman!” story. [TM & © EC Publications, Inc.]

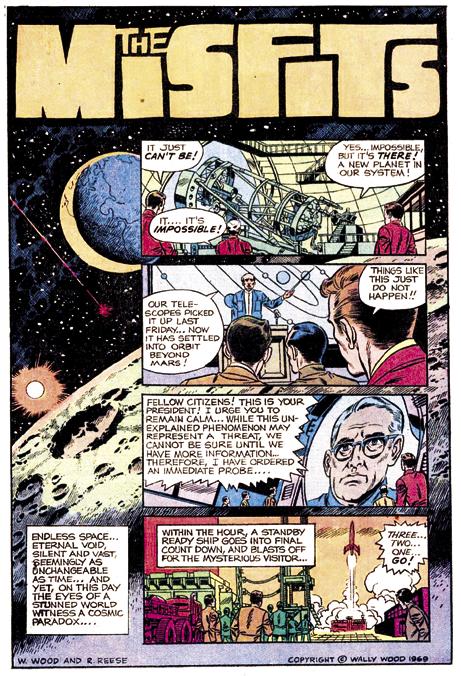

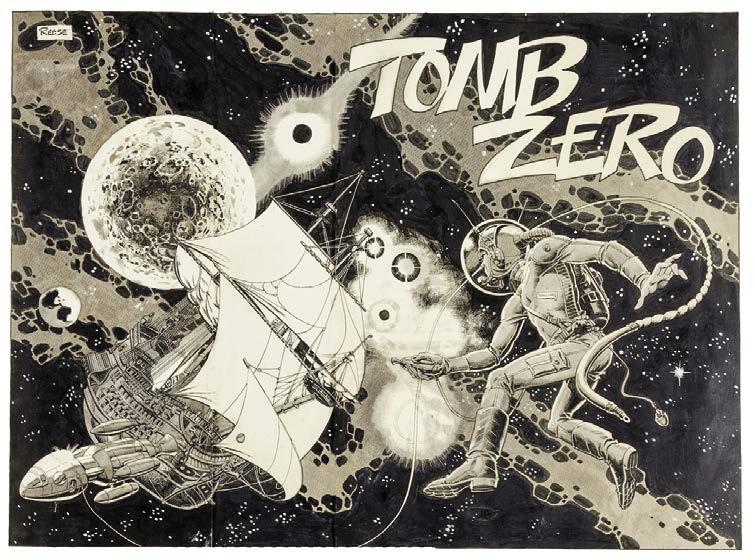

(Right:) Reese’s tribute to Wood’s Mad comicbook work, from the October 1971 issue of The National Lampoon, in which the newer publication gleefully skewered Mad magazine. [© National Lampoon or successors in interest.]

Monster’s Comic Crypt!

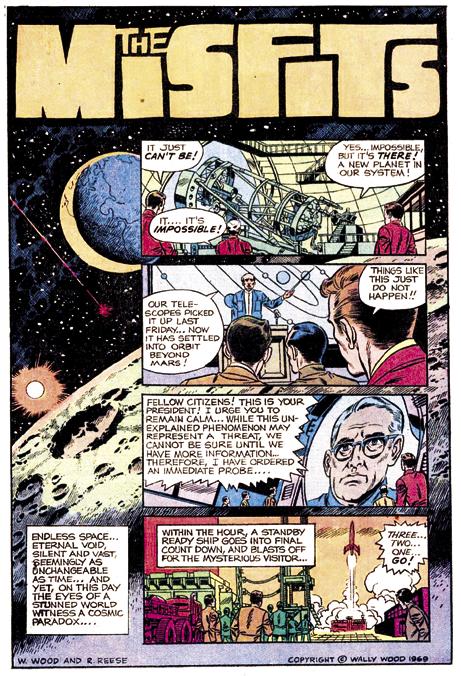

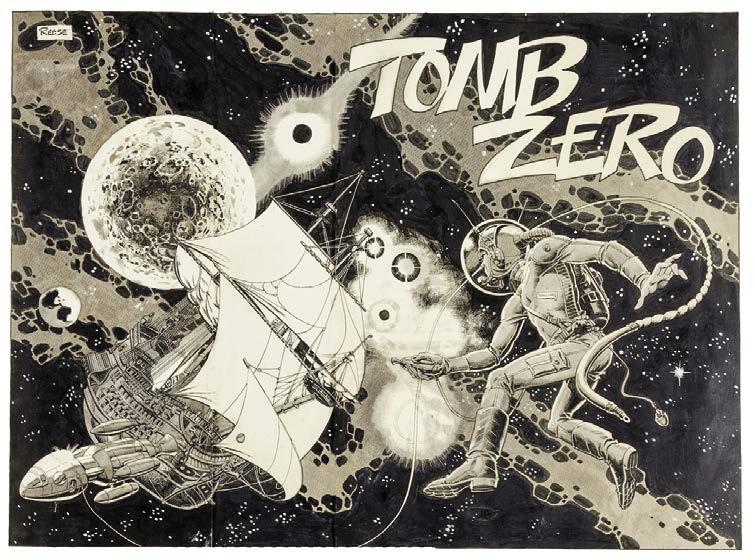

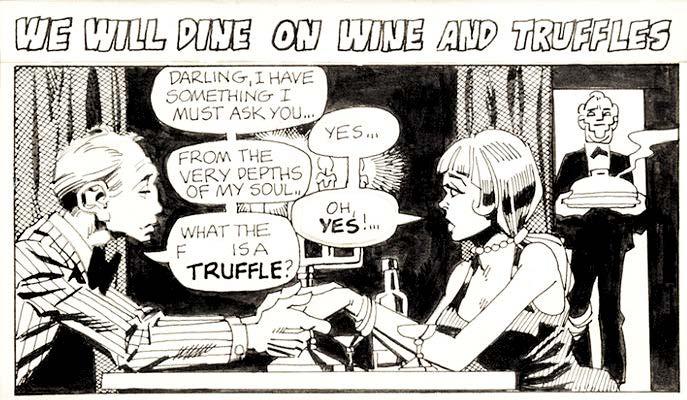

Last issue, Ralph Reese discussed working with the great comicbook artist Wally Wood, and how Woody became something of a surrogate father figure for a troubled teenager. With Wood’s help, Reese cleaned up his act and began getting work at Tower, DC, and elsewhere.

Now Reese leads us into the 1970s, as he talks about National Lampoon and Web of Horror, as well as Wood’s failed attempt to produce an adult comic for Warren Publications.

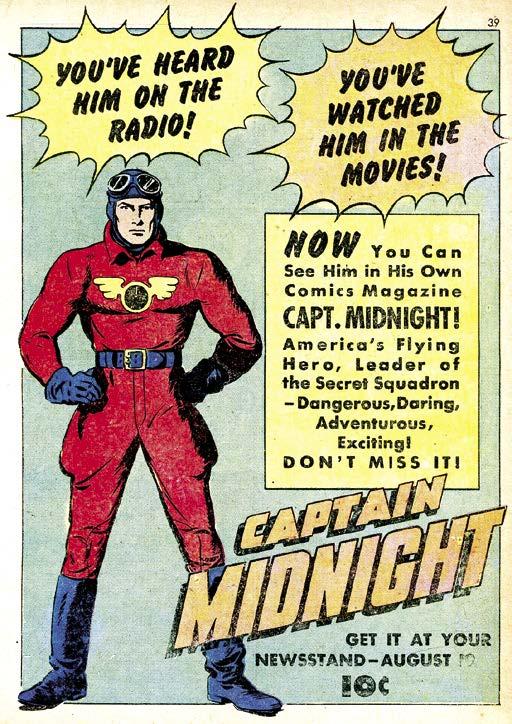

CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT The CLIFFHANGER! Chapter That Fell Off A Cliff

by Christopher Irving

Edited by P.C. Hamerlinck

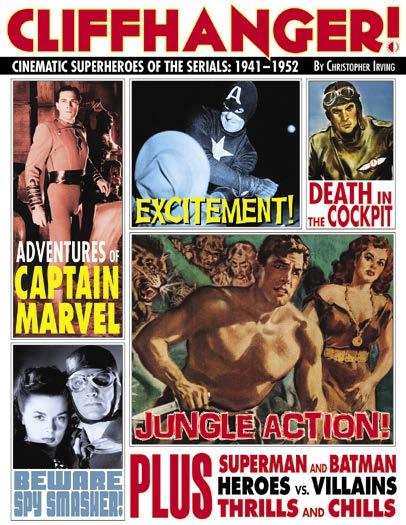

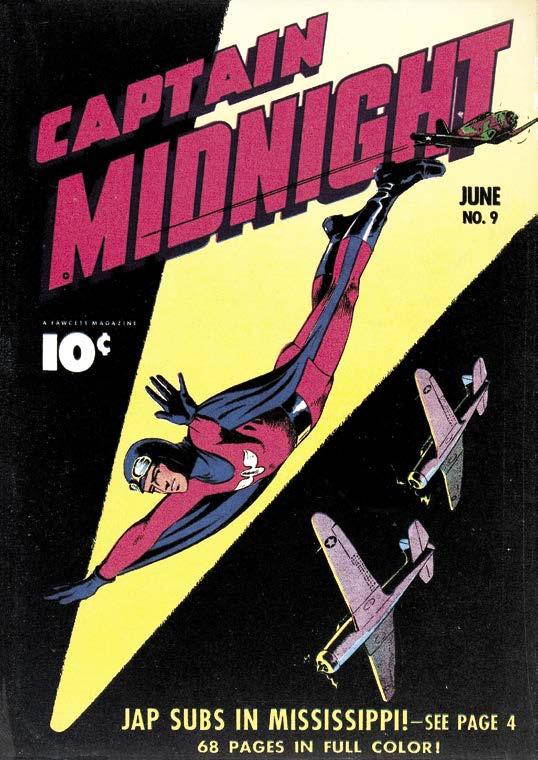

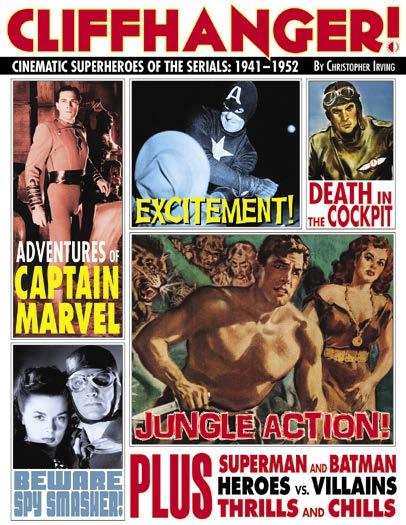

[FCA EDITOR’S INTRO: In Cliffhanger!, the rip-roaring book released this year by TwoMorrows, author Christopher Irving takes us on a thrilling journey back to the first on-screen comicbook-to-film adaptations, and a look at the comicbook and filmmaker creators who had a hand in bringing the heroes to glorious black-&-white life. From the origins of the theatrical serial to the rise of the genre in the 1930s and ’40s, individual chapters spotlight the comicbook super-heroes that appeared on Saturday matinee silver screens: Captain Marvel, Spy Smasher, Captain America, Batman, Superman, Blackhawk, and others. Part of Irving’s criteria for characters receiving their own center-stage spot in his book was that they need to have had their origins in comicbooks and not come from other forms of media. Hence, since he originated in an enormously popular radio program, Captain Midnight—brought to movie screens by Columbia Pictures in 1942—had to be excluded. Since Fawcett Publications launched their Captain Midnight comicbook series while the movie serial was still playing in theatres, we told Mr. Irving that we’d love to give his cut “Captain Midnight” chapter a home in FCA. So grab your secret decoder rings and enjoy… and when you’ve finished reading this article, order your copy of Cliffhanger! today.]

Captain Midnight was a singular character with a handful of different versions of himself, each one created to make the best of whatever media he was thrown into, with little synergy between each.

The good Captain first flew the airwaves as a regionally syndicated radio show on Chicago’s own WGN radio in 1938. Originally partnered with the Skelly Oil Company, Captain Midnight was picked up by Ovaltine as the new sponsor on September 30, 1940, and then syndicated on a national level. He was the creation of two writers, Robert M. Burtt and Willfred G. Moore, who had earlier created the once-successful aviator program The Air Adventures of Jimmie Allen, about a teen pilot. Captain Midnight was them taking what they’d learned from Jimmie, and making it work for a pre-World War II generation of kids.

The Captain Midnight radio show was a fifteen-minute serial that played daily Monday through Friday at 5:00 PM. Midnight was former World War I ace Albright, who flew a desperate and vital mission to capture the villainous Ivan Shark. When he flew in with the captured Shark at the exact stroke of midnight,

73

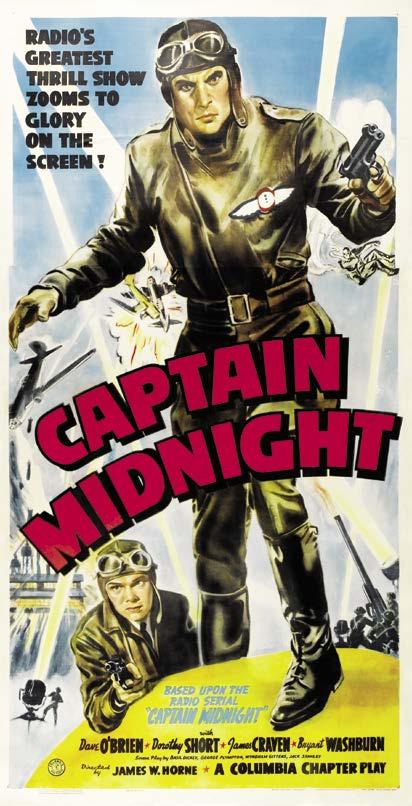

Captains Courageous

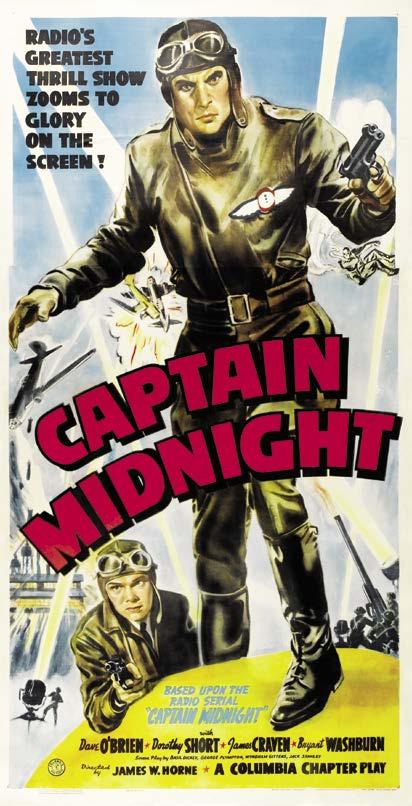

(Above:) Captain Midnight, played by Dave O’Brien, looms larger than life in this movie-serial poster from 1942, painted by Glenn Cravath. Image courtesy Heritage Auctions.

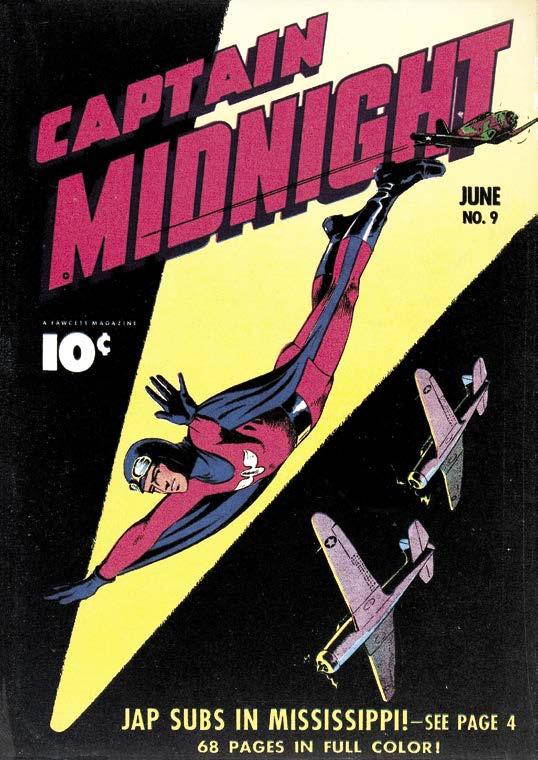

(Left:) The comicbook Captain Midnight #9 (June 1943) sported a beautifully drawn cover by Mac Raboy. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

Albright’s pal Major Steel declared, “To me—he will always be Captain Midnight!” A couple of decades later, the government put Captain Midnight in charge of his Special Squadron. In the lead with his plane The Sky King, Midnight’s rank was SS-1 and his crew all followed the SS rank in numbers. The Squadron included two kids, Chuck Ramsey and Joyce Ryan, as well as comic relief Ichabod “Ikky” M. Mudd, and was headed by his war buddy Steel. Midnight went after spies and saboteurs, most notably Ivan Shark (who slowly went from Russian to Japanese during wartime), heading his narcissistically named organization SHARK (Shark’s Henchmen, Assassins, Robbers, and Killers).

Listeners of the program could become members of the Secret Squadron fan club sponsored by Ovaltine. Membership wasn’t gained by taking spies down, but by simply mailing in a dime with a foil seal from an Ovaltine can. Membership also didn’t get kids their own plane, but a Code-o-graph (based on Midnight’s Maguffin-like secret device that Ivan Shark and his daughter Fury were always after) and a Secret Manual. The Code-o-graph was a badge that was gold in color and, though it went through variations over the years, generally featured a number and letter substitution code that could be decoded with a wheel set in the center. The radio show’s announcer spouted out the numbers for Secret Squadron members to hastily scrawl down and decode at the end of each episode.

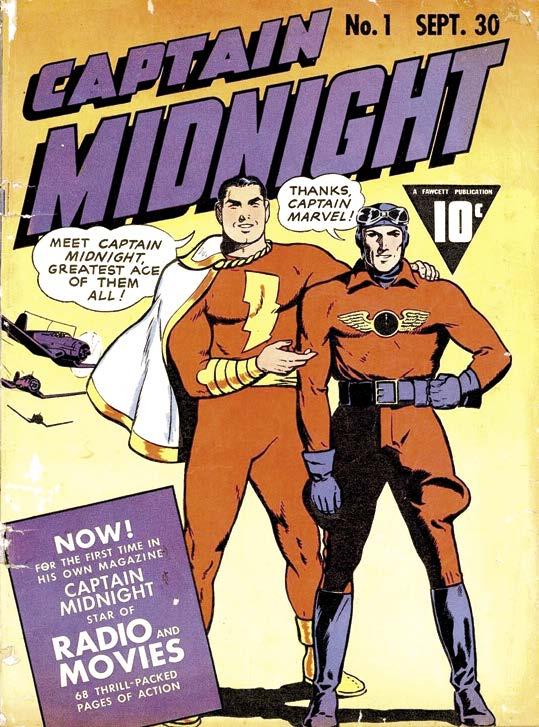

With the success of the radio show, Captain Midnight soon took a spot in various Whitman storybooks and Better Little Books, as well as comicbooks and comic strips. The Captain featured in the Captain Midnight and the Secret Squadron book of 1941 was a gaunt chap wearing an all-black flight suit with a winged clock emblem set at midnight emblazoned on his chest.

In 1941-42, Dell was the first publisher to bring Captain Midnight into comicbooks, with issues #57-64 of The Funnies and #76-78 of Popular Comics. Dell’s Captain Midnight, clad in brown leather, looked like a typical aviator hero and was slavishly adapted from the radio show’s first episodes.

A Captain Midnight newspaper comic strip appeared in 1942, released by the Chicago Sun Syndicate. The strip, written by Ed Herron (1942-44) and Russ Winterbotham, and illustrated by Erwin L. Hess, ran for several years and retained all of the radio series’ major characters. The strip deviated somewhat from its source material, but ultimately far less than other media interpretations looming on the horizon.

Then, Columbia produced a Captain Midnight movie serial, starring an actor once known for

playing a marijuana addict.

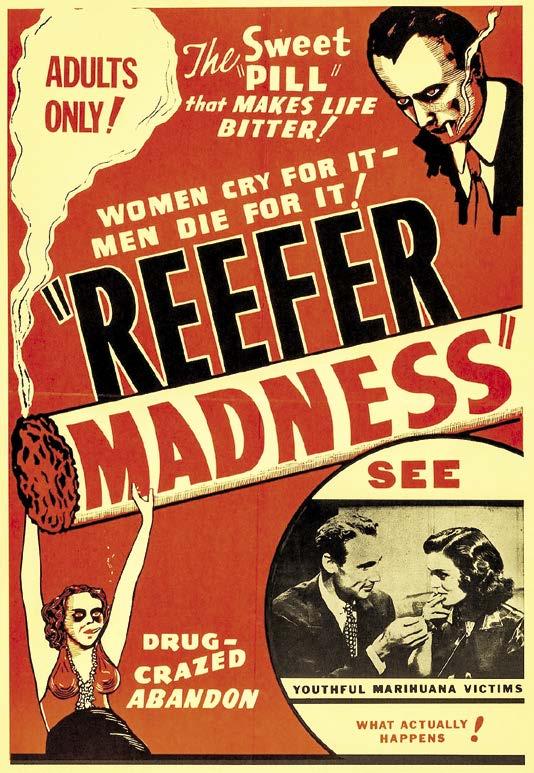

In the Captain Midnight lead role was handsome Dave O’Brien, born David Poole Fronabarger in Big Springs, Texas, on May 31, 1912. In 1936 he legally changed his name to David Barclay, but maintained the Dave O’Brien stage name. Dave kept himself busy as a stunt double and extra, mostly in Westerns, as well as modeling gigs on the side. He worked regularly in independent Westerns, such as the Texas Rangers series [Publishers Releasing Corporation], but never as the star.

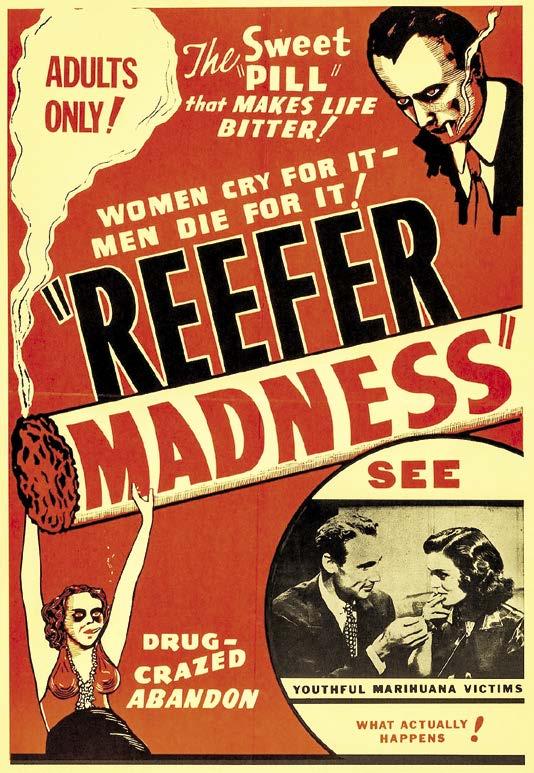

Dave’s most infamous role in the grand scheme of pop culture history was in 1936’s Reefer Madness (also known as Tell Your Children). In it, he plays a suited thug who introduces some nice high school kids to the wonders of marijuana and winds up getting nice girl Mary (played by his wife, Dorothy Short) killed after he assaults her. It ends with him in court, maniacally frothing at the mouth, as it’s declared that marijuana has rendered him “criminally insane” for the rest of his life.

The next time O’Brien acted alongside his wife was in Captain Midnight, with Dorothy coming in as Joyce (renamed Edwards from the radio’s Ryan).

Dorothy started acting with Laurel and Hardy, in their

74 FCA [Fawcett Collectors Of America]

“Hey, Kids—What Time Is It?”

(Left:) Dave O’Brien as Captain Midnight in the 1942 serial.

(Above:) A poster for the infamous 1936 movie Reefer Madness.

A pre-Midnight O’Brien portraying a drug-fueled maniac is the stuff of film legend. [TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

Hang Loose!

Dave O’Brien as Captain Midnight is but one of the movie-serial heroes who adorns this early version of cover of the new TwoMorrows book Cliffhanger! by Christopher Ivy. Another art spot replaced it on the printed cover. The book is available now at www.twomorrows.com. [© TwoMorrows Publishing.]

to get more fists on his face than anyone else.

Everyone talks as if they’re in the radio show, with dialogue perfectly annunciated. They’re the best-spoken serial cast ever.

After Captain Midnight, Dave O’Brien bought a 60-foot racing sailboat dubbed The White Cloud. He also co-starred in the PRC Texas Rangers series of films, appearing in 22 of them by the time he was finished.

O’Brien found his footing as a writer and producer with the Pete Smith Specialities line of one-reel shorts done with director Pete Smith for MGM until they ended in 1955. Using the name David Barclay, O’Brien often starred in these farcical documentaries on a variety of absurd subjects (from dealing with noisy theatre patrons to marital life). Sixteen of them were nominated for Oscars, with two of them winning.

ALTER EGO #185

He and Dorothy Short divorced in 1953, and he remarried a mere year after. In 1955, O’Brien joined up with comedian Red Skelton as a writer and double, an association that earned him an Emmy for outstanding writing.

Dave O’Brien suffered a fatal heart attack in 1969 while out on The White Cloud. One story has it that he died in the middle of showing someone how to do a backflip, a showman to the end. He was cremated and his ashes scattered over the sea.

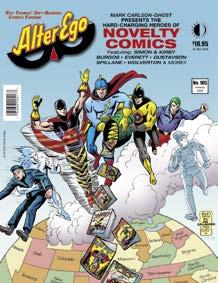

Presenting MARK CARLSON-GHOST’s stupendous study of the 1940s NOVELTY COMICS GROUP—with heroes like Blue Bolt, Target and the Targeteers, White Streak, Spacehawk, etc., produced by such Golden Age super-stars as JOE SIMON & JACK KIRBY, CARL BURGOS, BILL EVERETT, BASIL WOLVERTON, et al. Plus MICHAEL T. GILBERT in Mr. Monster’s Comic Crypt, FCA, and more!

(84-page FULL-COLOR magazine) $10.95 (Digital Edition) $4.99 https://twomorrows.com/index.php?main_page=product_info&cPath=98_55&products_id=1768

Luana Walters wasn’t as fortunate as her one-time co-star. Her husband of nine years, actor Max Hoffman, Jr., died of an accidental overdose of sleeping pills in 1945, and she found herself back out in Hollywood the next year. The roles weren’t there for her as they had been before and, by her death in May 1965, she was relegated to

Captains Of [The Comicbook] Industry

78 FCA [Fawcett Collectors Of America]

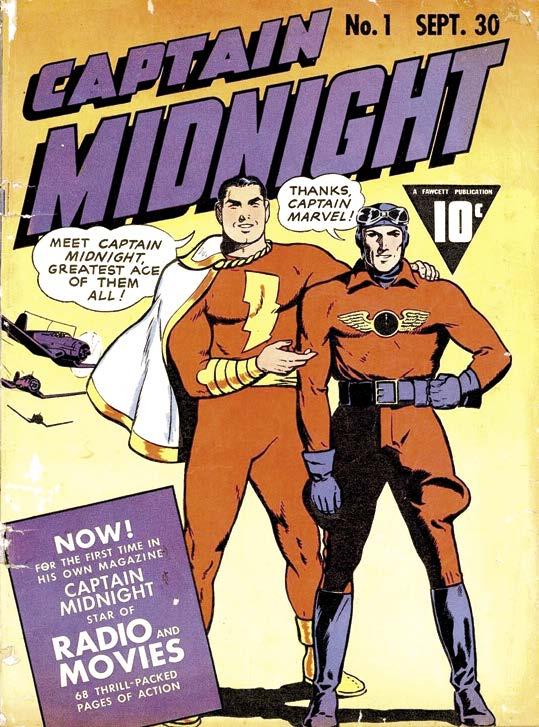

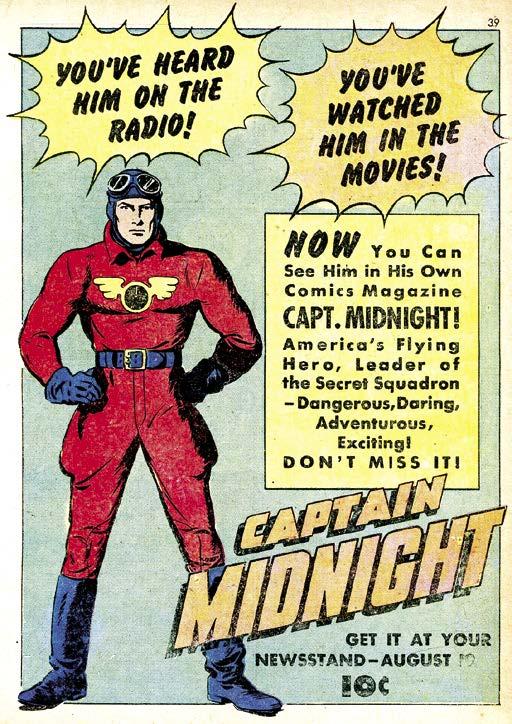

(Below:) Captain Marvel himself welcomes a fellow officer into the Fawcett fold on the cover of Captain Midnight #1 (Sept. 1942)—while a full-page ad appearing in various Fawcett comics calls attention to the company’s latest hero. Art by the Jack Binder Studio. [Shazam hero TM & © DC Comics; other art TM & © the respective trademark & copyright holders.]

IF YOU ENJOYED THIS PREVIEW, CLICK THE LINK TO ORDER

THIS ISSUE IN PRINT OR DIGITAL FORMAT!