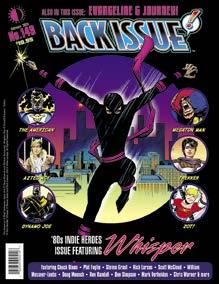

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Michael Eury

PUBLISHER

John Morrow

DESIGNER

Rich J. Fowlks

COVER ARTIST

Norm Breyfogle

(Originally produced as the cover of First Comics’ Whisper #4, Dec. 1986. Art scan courtesy of Heritage Auctions.)

COVER COLORIST

Glenn Whitmore

COVER DESIGNER

Michael Kronenberg

PROOFREADER

Kevin Sharp

SPECIAL THANKS

G. K. Abraham

Chuck Austen

Dell Barras

Kurt Busiek

Jarrod Buttery

Ed Catto

Comic Connect

Dan Day

Cecil Disharoon

Chuck Dixon

Ben Dunn

Matt Feazell

Phil Foglio

Stephan Friedt

Alex Grand

Steven Grant

Bob Harrison Heritage Auctions

Dan Johnson

Mike Jones

Todd Klein

Rich Larson

Heidi MacDonald

Don Markstein’s Toonapedia

Scott McCloud

William MessnerLoebs

Doug Moench

Luigi Novi

Amanda Powers

Tom Powers

Ron Randall Reading Is Fun. Not Mental

Doug Rice

Don Simpson

Jim Thompson

Mark Verheiden

Chris Warner

Marv Wolfman

Thomas Yeates

Catherine Yronwode

Don’t STEAL our Digital Editions!

BACK ISSUE™ issue 149, February 2024 (ISSN 1932-6904) is published monthly (except Jan., March, May, and Oct.) by TwoMorrows Publishing, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614, USA. Phone: (919) 449-0344. Periodicals postage paid at Raleigh, NC. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Back Issue, c/o TwoMorrows, 10407 Bedfordtown Drive, Raleigh, NC 27614

Michael Eury, Editor-in-Chief. John Morrow, Publisher. Editorial Office: BACK ISSUE, c/o Michael Eury, Editor-in-Chief, 112 Fairmount Way, New Bern, NC 28562. Email: euryman@gmail.com. Eight-issue subscriptions: $97 Economy US, $147 International, $39 Digital. Please send subscription orders and funds to TwoMorrows, NOT to the editorial office. Cover artwork by Norm Breyfogle. The American © Mark Verheiden. Aztec Ace © Doug Moench and Michael Hernandez. Dynamo Joe © Dour Rice. Megaton Man © Donald E. Simpson. Trekker © Ron Randall. Whisper © Steven Grant and Rich Larson. Zot! © Silver Linings. All Rights Reserved. All editorial matter © 2024 TwoMorrows and Michael Eury. Printed in China. FIRST PRINTING

Megaton Man is one of those characters that everyone always remembers once he or she has encountered his wildly brilliant metaadventures that offer Don Simpson’s incisive commentary on the monolithic universes of DC and Marvel Comics. But the saga of Megaton Man— which began in 1984 with Kitchen Sink Press, continued through Don’s self-publishing efforts via Bizarre Heroes , and is rising stronger than ever through his recent work with the character in X-Amount of Comics: 1963 (WhenElse?!) Annual is one that serves as a great inspiration to any aspiring creator who wishes to forge an original path in an often corporate-dominated comic-book industry. It is thereby my distinct pleasure to share with BACK ISSUE the following conversation I had with Don concerning the four-decade story of the indomitable Man of Molecules.

– Tom Powers

– Tom Powers

TOM POWERS: When you were creating Megaton Man #1 (Nov. 1984), you were in your early 20s. Could you please talk about what went into making this historic comic? (On your blog, you discuss having to wash dishes in order to support yourself while putting this issue together.)

DON SIMPSON: I’d been drawing since I was five; I was just one of those kids who never stopped. At the age of ten, the summer of 1972, I discovered comics and fell in love with them. I’d gotten some free DC and other comics in second grade, but when I began buying them myself, I gravitated toward Marvel. There were older kids in the neighborhood who had stacks of stuff dating back to the mid-’60s, so I could get my hands on that.

MAD magazine was an influence, Dr. Seuss before that. Doonesbury and Funky Winkerbean and Peanuts were in the newspaper. Nick Meglin and

Shouldering the Burden

Don Simpson’s Megaton Man #1 (Nov. 1984), published by Kitchen Sink Press.

SIMPSON: That’s what I’m talking about. I was doing Watchmen before Watchmen. Keep in mind I was making all this stuff up as I went along; I never had a master plan. Because I was being published by a legacy underground publisher, and because I was doing comedy, ostensibly—and because Megaton Man was $2.00 when Marvel and DC comics were 60 cents—I felt I could push things a little more over the PG line. We weren’t subject to the Comics Code.

So, I had nudity—the See-Thru Girl, for starters. She could turn naked with but a thought! And Megaton Man—basically a Superman parody visiting the Marvel Universe—he has this fling with the eye candy of the Fantastic Four—my Megatropolis Quartet. Superman meeting the FF was a Not Brand Echh trope.

And the way I write stories… I should back up for a moment. I made them up as I went along. I was just trying to think, “What would be funny?” So, at the end of issue #1, the See-Thru Girl and Pammy—the hero’s two love interests—leave town. They split. I had nothing planned after that. And I mailed off my photocopies, and I have a publisher in Wisconsin asking me, “Can you do this bimonthly?” Sure! But I had not built a world.

So, what happens next? Well, the girls are off to Ann Arbor, and Megaton Man joins the Megatropolis Quartet—but there’s this friction, because Rex Rigid, the scientist-husband of the See-Thru Girl, knows there’s been some hanky-panky, and he’s a malevolent sort. So, Megaton Man thinks Rex is trying to kill him when he’s being turned into Captain Megaton Man.

My point is that I was always coming up with something funny, then taking it seriously, and asking, “What happens next?” In this case, wouldn’t it be funny if the See-Thru Girl goes off to college, trying to forget her failed marriage to a mad scientist three times her age and trying to forget her fling with the Man of Molecules—but then she realizes she’s pregnant?

So, I’m just making up stuff that I think is funny, but subconsciously, it’s going to a very f***ed-up place. And of course, Alan Moore is going to rip that off and go to town [laughter].

When I met him, I had just completed Megaton Man #6 (Oct. 1985), which did a spoof of Swamp Thing . I have this character—not even a character, really—a sawdust dummy that gets soaked in Megasoldier serum. Megaton Man, when he needs to ditch his day job as Trent Phloog, cub reporter at The Manhattan Project, puts this sawdust dummy in his chair at his desk, and he runs off and does his Megaton Man thing. And one day, the evildoers who want to kill Megaton Man assassinate the sawdust dummy instead.

The dummy ends up in the swamp, and I try to ink like John Totleben, and the captions read, “But he isn’t Trent Phloog. He never will be Trent Phloog. He never was Trent Phloog.”

So, I’m carrying these photocopies in my portfolio, and I’m walking through the dealers’ room in San Diego [Comic-Con], 1985, to and from Artists’ Alley, and I run into Alan Moore. And I show him this page. He reads it out loud and says, “Brilliant writing!” That evening, DC hosted a party down by the bay, and I’m at a table with Alan and Maggie Thompson, and Alan says to me, “By the way, I’m ripping off Megaton Man—not really.” And he explains that Dr. Manhattan is his take on a nuclearpowered character. And sure enough, a year later, Watchmen #4 has my “on patrol” scene with Megaton Man and the See-Thru Girl going on patrol—really, just an excuse to hook up, and Dave Gibbons has the crossword-puzzle skyline and everything.

Now, I was very flattered. But of course, it’s the curse of the clown to not be taken seriously, whereas the Shakespearean

dramatist is creating High Art. But, whatever. I thought it was all friendly back-and-forth plagiarism—I mean, discourse!

But I ran across the fifth issue of Megaton Man recently— very dark for a superhero parody, because in a flashback, Rex is slapping around Stella, the See-Thru Girl, because he knows she’s been cheating on him. And he’s very menacing. And she beats him up right back. And I thought, “Wow—people are always talking about Alan Moore’s influence, but I think he may have picked up a thing or two from me!”

POWERS: With Megaton Man #5 (Aug. 1985), you begin an interesting subplot of sending journalist Pamela Jointly and Stella back to college in Ann Arbor, Michigan. (Likewise, Trent eventually becomes their roommate, but they run the household.) How do these storylines provide commentary upon their DC and Marvel counterparts, Lois Lane and Susan Storm Richards (or the traditional role of the female sidekick in general), in regard to their agency—or lack thereof?

SIMPSON: Again, I was just following the logic of the last joke I made. So, Megaton Man loses his power at the end of issue #10 (June 1986), the end of the series, and he’s just a civilian again, wearing this baggy costume that no longer fits him, because he had huge muscles before. But they’re gone. And he realizes the loves of his life—if he could make up his mind—are also gone, and one of them is going to have his kid. So, he’s off to Ann Arbor.

Now, I did seven issues of Border Worlds and started freelancing for DC on Wasteland. But eventually I started to wonder, “Whatever became of Trent and Stella and Pammy?”

The influences were really Doonesbury and The Big Chill more than Marvel and DC, as well as my own life living with roommates in Detroit and knowing lots of creative types in bohemia. I was an art-school dropout by this point, but I knew a lot of college students my age, musicians, actors, and so on. We

Writer Steven Grant’s ninja character Whisper first saw the light of day in a two-issue run from Capital Comics (Dec. 1983–Mar. 1984). In a “Pro2Pro” interview with Grant and Whisper artist Norm Breyfogle that appeared in BACK ISSUE #49 (Feb. 2017), Grant told me: “I was living in New York and taking a train home to Madison, Wisconsin, where I grew up. I read a cheap paperback, supposedly factual, about ninjas to pass the time. At the time ninjas were just beginning to work their way into the American psyche. I knew that while ‘ninjas’ did exist in feudal Japan—they were essentially messengers for nobles—what we think of a ‘the ninja,’ the black-garbed, shuriken-throwing, virtually unstoppable magical assassins, were the product of nationalistic interwar Japanese pulp fiction. In other words, complete BS. I mean, really, if ninjas as we think of them ever existed, do you really think Japan could’ve lost WWII?”

Rich Larson was the artist of Capital’s two issues of Whisper . With the demise of Capital Comics, Whisper moved to First Comics, continuing her story in Whisper Special (Nov. 1985), also illustrated by Larson. From there, she became a part of First’s anthology series First Adventure (Dec. 1985–Apr. 1986), also with art by Rich Larson for all five issues of its run. [ Editor’s note: Joining the “Whisper” feature in all five issues of the First Adventures anthology was “Dynamo Joe,” another of this issue’s indie heroes. Issues #1–4 also included an adventure starring “Blaze Barlow and the Eternity Command.”]

RICH LARSON, THE ORIGINAL ARTIST

Rich Larson is probably best known for his collaborations with his art partner Steve Fastner. From the Fastner/Larson bio page on their DeviantArt page: “We’re Steve Fastner (airbrush artist) and Rich Larson (penciler), and we’ve worked together on fantasy and comics-related art since 1976. … Most of our larger paintings are airbrushed by Steve onto art board over Rich’s pencils. More of our work, including some comics, can be seen at fastnerandlarson.com .” [ Editor’s note: See BACK ISSUE #83, our “International Heroes” issue, for its Fastner/Larson X-Men vs. Alpha Fight cover and an interview with the artists about their collaboration.]

I spoke with Rich Larson via email about the experience of working with Steven Grant as the original Whisper illustrator:

STEPHAN FRIEDT: How did you and Steven Grant come together as a team?

RICH LARSON: I’m dredging this up from the synaptic depths, so some of the details might not be entirely accurate. In the mid to late ’70s, I was doing stories and covers for Charlton’s ghost comics and had done a few stories for undergrounds like Denis Kitchen’s Bizarre Sex and for “ground level” comics like Sal Q’s Hot Stuf’ . I believe Sal put Steven Grant in touch with me, and we did a couple of stories together—the profoundly impenetrable (at least to me) “Nimrod Fusion” for Mike Friedrich’s Imagine and a neat little eco-disaster fable called “The Walls of the City” for Hot Stuf’

Making Noise for ‘Whisper’

Duck! Whisper’s got you in her sights! Original art for an early promotional poster for Capital Comics’ Whisper series, and the printed poster. Art by and courtesy of Rich Larson.

Grand Larson-y (insets) Covers to the two Capital issues, Whisper #1 (Dec. 1983) and #2 (Mar. 1984). Issue #1’s cover by Michael Golden, #2’s by Larson. (main) Capital Comics’ demise kept this dynamite Rich Larson cover art from appearing as the cover of issue #4, which was not published by the company. Instead, this piece surfaced on the intro page of the 1985 Whisper Special. Scan courtesy of the artist.

I think Steven suggested me as a possible artist when he brought Whisper to Capital Comics, and to this day, I’m not sure why Capital went along with that. I was doing freelance advertising art at the time and had only done short comic stories previously. I ended up wildly underestimating the amount of time it would take to do a full book, and I had to ask Dennis Wolf, on zero notice, if he would be willing to drop whatever he was working on to do the inking and lettering. He was a terrific artist (see Eclipse’s Overload magazine) and he absolutely saved the first issue.

Grant was either in Wisconsin or New York City, and I was in Minnesota, so the way we worked together was by full script via mail. I was chronically behind schedule, so I don’t remember much in the way of back-and-forth; luckily Steven put everything necessary to visualize the story into his scripts, so there wasn’t the need for a lot of discussion.

FRIEDT: What was the inspiration for your work on Whisper?

LARSON: I hate to say it, but Whisper was probably close to the least-inspired published work I’ve ever done. Part of that was because, as primarily a fantasy/horror guy, I just wasn’t a good fit for the material. I was always trying to figure out a look for the art that would complement the story and that I could pull off. The other part was that when I started working on the art for the first issue, I was already in the middle of other things— ad work, mostly. I was trying to do several things at once, and constantly falling behind.

Until about the third and fourth issues (which First Comics packaged together as the Whisper Special), when I decided to concentrate on what I was doing, it was all I could do to just move the plot along from A to B. There was no room for inspiration. But by the third and fourth issues, what inspired me was the desire to finally bring a uniform look and a base level of competence to the visuals. (See near the end of the interview for how well that worked out.)

FRIEDT: What influenced you when you worked on the character? Movies? TV?

LARSON: Honestly, I was influenced by the desire not to do another martial-arts character. The genre has never much resonated with me, and I don’t think Steven ever mentioned wanting to pay homage either. My sense was that the rolling dumpster fire that Alex’s personal life [Whisper’s real name is Alex Devin ed.] was going to be as a result of becoming a pawn in the battle between the feds and the Japanese underworld was the main attraction and that the ninja aspect was going to be subservient to that. I think Steven was telegraphing this when, early on, a major bad guy confides in Alex that there’s no such thing as a ninja; their existence is just a myth the underworld elites continued to propagate to gain and keep power in the Yakuza. (Although the character could have been lying through his teeth to throw Alex and the reader off. With Grant, you never know.)

FRIEDT: What was your goal in developing the character?

LARSON: Although we were credited as cocreators, the character and story were always entirely Steven’s. I had an idea of how he felt about heroes and heroics, and so I tried to keep the overall look as far away as possible from the way those things had traditionally been handled in comics.

As far as Alex’s physical appearance was concerned, since her early ninjutsu training was to help her recover from childhood polio, I wanted to keep her slender and (by comic-book standards) almost a bit frail looking—just in case things started going too well in her life to suit Steven, and he decided to have her to relapse into paralysis. I suppose the costume was a concession to the superhero genre. The standard issue ninja suit wasn’t something I wanted to be drawing Alex in over and over, but I was also concerned with not ending up with something like another Elektra. Since Whisper wasn’t going to be doing superhero stuff, and Alex wasn’t configured to be eye candy, the costume itself had to provide a significant portion of the visual interest without being overly “costume-y.” I tried to keep it simple, dramatic, and moderately plausible. And I wanted Alex’s vulnerability to show through. It was nice to see future Whisper artists continue to go with it.

Comics’ Other Wolverine Forget DC’s Tomahawk—William Messner-Loebs’ Journey: The Adventures of Wolverine MacAlistaire is your comic-book pathway to the American Frontier. Original artwork from Journey #1 (Mar. 1983), courtesy of Heritage Auctions (www.ha.com).

It is only in retrospect that we realize the ’70s and particularly ’80s books that many of us grew up with, that BACK ISSUE magazine is devoted to, are further away and more distant and distinct from kids and young adults today than the World War II comics of the ’40s, the Golden Age of Comics, were to our generation. Most of the books of the ’40s were published during the nascent years of the medium, and that is reflected in the art and storytelling. As much as we may thrill to a Mac Raboy–drawn Captain Marvel, Jr. or Matt Baker Phantom Lady or Simon & Kirby Captain America or Alex Schomburg covers, most Golden Age stories themselves are not going to be confused with great storytelling… whereas the books of the ’80s, spearheaded by creators like Miller and Moore and Moench and Giffen and DeMatteis, showed that the medium had arrived and grown up. These were young men telling personal, sophisticated stories in the medium of the comic book— atypical stories that resonated with them, and therefore resonated with the disaffected youth and young adults who were picking up these books at the time.

And the more that storytelling holds up, the books of the ’80s are to some extent the standard by which even modern audiences judge great storytelling. There is a reason Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen and Swamp Thing remain perennial bestsellers, and works we revisit over and over again in various mediums.

Because the ode of the Hopeful Young Man does not die. It is something we can relate to, especially as our culture gets more unreasoning and arguably barbaric, the visions of these challenging storytellers are ever more unusual and sophisticated.

And arguably nothing represents that as well as writer/ artist William Francis Messner - Loebs ’ (Bill Loebs, to friends and colleagues; Messner is the family name of his wife and collaborator, Nadine) body of work, specifically his Journey: The Adventures of Wolverine MacAlistaire (henceforth Journey ).

First seen in 1983 in a backup story in Cerebus #48, Journey is a black-&-white feature chronicling the wistful treks of Joshua “Wolverine” MacAlistaire in the American Frontier of the 19th century. Titled “Search,” this first Journey story, which concludes in Cerebus #49, is an adept and assured introduction to the series’ time and place. Loebs’ deft penciling, inking, and panel compositions, and his use of shading, blacks, and negative space, combined with a rich, gripping, and immediately addictive narrative, makes for a smashing conclusion to the first story and a mesmerizing introduction to an immediately iconic character. Soon spinning off into its own title, Journey was originally to be a sixissue miniseries from publisher Aardvark-Vanaheim. Journey ultimately ran 27 issues, through 1986, switching to publisher Fantagraphics Books with its 15th issue.

You can find two IDW collections collecting the whole Journey series. Unfortunately, the printing isn’t great on those collections, and you lose much of Bill’s light, detailed linework and subtle shading and shadowing, plus much of his storytelling. The original issues remain the best way to sample this under-championed bit of Americana, this Mark Twain of the comics medium. Journey is a body of work that deserves a remastered hardcover edition, to make accessible to a new generation this important, whimsical, and fun series that is arguably the best comic book ever done about the spirit of the American frontier, tall tales and all.

In early 2023 I had the good fortune of interviewing Mr. Loebs about Journey. Hopefully this interview will serve as a primer for the uninitiated and a small impetus toward a remastered, deluxe reprinting of his epic work.

– G. K. AbrahamCover Story

(top) Loebs’ Journey often featured wraparound covers, some of a single, expanded scene, and others—like the front and back covers to issue #1, shown here—of two different images. (bottom) MacAlistaire makes a grisly discovery on the cover of Journey #2. Original cover art courtesy of Heritage.

ABRAHAM: Because she was actually the publisher of AardvarkVanaheim’s comics?

LOEBS: She was the publisher, and he was the editor-in-chief. As their marriage fell apart and other things happened because of that, they changed positions in the company considerably. But that was a long time ago, and Dave and Deni have been extremely helpful as I get things done, and get published and all of that. I think we’ve all sort of kissed and made up at this point.

ABRAHAM: I remember reading Deni’s articles in Journey, where she would discuss you and [Messner-Loebs’ wife] Nadine and the glowing praise she had for you both.

LOEBS: She was extremely generous.

ABRAHAM: You stayed on Journey for three years, I believe, 27 issues. Did you expect to stay on that long or just four issues and done?

LOEBS: Six issues. Originally we were thinking it would be a six-issue miniseries, but Deni came to me and wanted it to continue, so that’s what we did.

The mid-1980s were a great time for animated fare for a lifelong science-fiction fan like me. My local UHF television stations were hitting me where I lived with shows like Voltron, Tranzor Z, and The Transformers. These shows had what I liked: robots. Big, honking robots. I didn’t know it at the time, but the first two shows were also laying the seeds for my love of anime.

As these shows were taking over syndicated television, a comicbook series at First Comics was beginning to find an audience that had a hankering for giant robots, too. But where the robots were all the rage on television, there was very little at the local comics shops like Dynamo Joe.

Set in the future, Dynamo Joe concerns the adventures of the two-man crew manning a Dynamo Class Robosoldier, a giant robot that was part of a fleet of robots engaged in an intergalactic war against the invading race known as the Mellenares. Dynamo Joe’s crew included pilot Sgt. Elanian Daro, a former captain of the Imperium Officers Corp, and mechanic Pomru Purrwakkawakka, a member of the feline alien race, the Tavitan. The series was high adventure with some humor and a lot of heart, and it stands as one of the best science-fiction comics of the 1980s.

The series was inspired by its creator’s love of anime. These days, anime is a worldwide phenomenon, but at the time Dynamo Joe came out, young fans like me were just getting a small taste of the animated magic arriving here from Japan. Doug Rice, though, had been ahead of the curve.

COLLEGE DAYS

To get the full story behind Dynamo Joe , we have to discuss the friendship that made the series possible in the first place. Doug Rice and the man who wrote the majority of the Dynamo Joe stories, Phil Foglio, first met through their mutual love of science fiction.

“Phil and I go back to college,” recalls Rice. “He was in the DePaul University Society of Science Fiction Freaks and Armchair Speculators and I was with the University of Illinois Circle Campus Science Fiction Group, and each group came to one another’s meetings and we got a chance to socialize, This was when the Chicago science-fiction conventions started up again.”

“All of us at the DePaul University Science Fiction Society, all four us, went over to Circle Campus because that group had a real clubhouse and everything,” adds Foglio. “They put out a fanzine, so they obviously knew what the hell they were doing. [We became friends because] Doug was an artist and I was an artist, and from ’74 to ’76, we actually shared an apartment.”

Rice and Foglio began attending sci-fi conventions together and entering art shows at these events. It was through these shows they first began to get noticed in the fandom circles and then later began to gain work as professionals. But it was one convention road trip in particular that was the genesis for Dynamo Joe. Thing was, it wasn’t anything that happened at the con that launched destiny into motion. It was a visit to Foglio’s hometown and a chance encounter at a local shop that set things off.

NO PLACE LIKE HOME

Go, Go, Joe!

Get ready for some giant robot action! First Comics’

Dynamo Joe #1 (May 1986). Cover by Doug Rice.

“I have been a fan of giant robots since 1976 when I was at a Star Trek convention in New York City,” recalls Rice. “It was the big one when they were to announce Star Trek: The Motion Picture, before the NYC fire marshal shut the overcrowded event down before [Gene] Roddenberry even arrived. Phil was going to take me to meet his family.”

“I grew up in a little town called Hartsdale. It’s right next door to Scarsdale, which everybody has heard of,” says Foglio. “Even back then, Hartsdale had a large Japanese community, and they had Japanese stores.”

“As we were driving through town, there was a shop on the corner,” adds Rice. “It was a Japanese store, a grocery store or general store, whatever, and they had a poster in the window of a giant robot. [It was] from a TV show as it turned out, and I said, ‘Before we leave, I want to go to that shop!’”

The poster that caught Rice’s eye was an advertisement for a Japanese animated show called Yūsha Raidīn. [Editor’s note: Yūsha Raidīn, a.k.a. Brave Raideen, originally ran from 1975 through 1976 on Nihon Educational Television before being internationally syndicated.] “This was 1976, and the series had just come out and was being shown on a Japanese language UHF channel on the weekends,” says Rice. “I got a chance to watch the show, and it blew my mind. This was a time when the biggest animated show was Scooby-Doo, so there was nothing like this [on American television]. It made American cartoons look like they were in black and white. The colors were just so vibrant. The action was incredible, the design work was amazing. Plus the music and sound effects were over the top. This thing had energy to spare. It was just wonderful throughout with all the ideas it played with, like using giant kaiju against giant robots and having the robots transform from one thing to another. It was just done so well. There was a lot of real animation going on there.”

This wasn’t exactly Rice’s first exposure to what was called “Japanimation” at the time, and as Rice further notes, “doaga” before World War II. “I was into Astro Boy when in first aired in the US, in 1963, in Chicago on early Sunday mornings,” recalls Rice. “This show vanished abruptly when it was pre-empted by the funeral ceremonies for JFK; gone, never to return.” That early import to the States also had an impact on Foglio, too. “I first discovered what you would call anime back in the ’60s when I discovered Astro Boy on TV and that made a huge impression on me,” says Foglio. “I didn’t know it was a particular style, but there were a lot of other anime shows at that time. There was also Simba, the White Lion and Marine Boy. I was like, ‘This is good stuff! I am all over this!’ But then it kind of went away [for a while]. There just wasn’t that much of it, but it had a profound effect on my developing art style.”

Getting the chance to watch Yūsha Raidīn that fateful weekend started Rice down the anime rabbit hole. But what cemented his passion for it was the visit to the store where he had spied that initial poster. “[We went to the store] and Doug picked up a bunch of stuff,” says Foglio. “I thought it was nice, but Doug was instantly smitten with it. It really hit him where he lived. And that began his journey into anime and giant robots in particular.”

“I went to that store and inside there were manga and models and posters and I just bought one of everything,” says Rice. “And I became a fan right from that moment on. When I got home to Chicago, I had to hunt around for similar shops and

Robotic Inspirations

(top left) Young Doug Rice was captivated by the Japanese import Yūsha Raidīn, a.k.a. Brave Raideen. (top right) Rice’s pre–Dynamo Joe mecha character, Champion: SOLAR 7, in Just Imagine Comics & Stories #7. (bottom left) Dynamo Joe issues #2 and (bottom right) 4.

they had manga, at least, so I was able immerse myself in the monthly books that were coming out.”

For Rice, this local shop not only offered a first glimpse to the manga that Japan was producing at the time, but it also afforded a look at what drove the sales of the books and made them so popular. “These manga came with all kinds of goodies packed in these big plastic bags like posters and other tchotchkes along with the manga, which were the size of a small phone book. They really pushed the products, and the fans loved it. And giant robots led the way. They were the ones who really did the merchandising.”

THE FIRST (COMICS) JOB

After college, both Rice and Foglio put their artistic skills to good use. Rice would come to work for First Comics, and it was there he got the chance to pitch Dynamo Joe. “I was offered a chance to do the backup feature for a book called Mars at First Comics,” says Rice. [Editor’s note: BACK ISSUE took a trip to Mars way back in issue #14.] At the time, Rice was doing paste-ups on all the First Comics titles, and working on covers, the letters pages, and the advertising as part of the art staff. “Mars was a science-fiction title and the artists were having a hard time keeping a monthly schedule, which was imperative back then because you had to make that monthly deadline no matter what. That was the only necessity that kept a small company like First Comics being distributed by the major comic-book distributors. In order to keep that monthly title going, First decided to take the last eight pages of the book

Although popular in movies and books for many years, nuns were seldom depicted in comics outside of Treasure Chest and Catholic Comics. These wholesome series routinely offered stories where nuns were important characters and sometimes even featured on the covers.

One other exception was Dell’s four-issue series The Flying Nun. This was adapted from a 1960s TV show about an order of nuns in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Sister Bertrille, played by Sally Field, was an idealistic nun who could tilt her cornette (headpiece) into the winds in such a way that she could fly.

What do The Flying Nun , Bewitched , a nd I Dream of Jeannie have in common? In each of these, the female protagonist had a power or ability that needed to be kept secret from the world at large.

The theme of secrecy continued in 1984 with the story of a nun with a secret life.

Imagine how jarring it was in when Comico Primer #6 introduced the world to a nun with a gun! Set in a near-future world, readers met a nun who was secretly an assassin for the Catholic Church. Her name was Sister Evangeline.

PRIMING THE PUMP

Today it might be called “a soft launch,” but a short feature in Comico Primer #6 (Feb. 1984) introduced fans to Evangeline and to her creators, Charles Dixon and Judith Hunt.

The cover featured Evangeline and summed up the series’ premise with the juxtaposition of a nun praying, complete with stained glass in the background, contrasted with a full-figure illustration of the character in a ready-for-action style jumpsuit, pistol in hand. Editors Matt Wagner [yes— that Matt Wagner! —ed. ] and Reggie Byers proudly trumpeted the series in the text page:

The big news for this issue is, of course, Evangeline. The exciting tale of how the church handles its future is the brain-child of Charles Dixon and Judith Hunt, a husband and wife team that will be expanding their legend to premier in its own color title in February. This series is sure to be a winner, so watch out for it.

This initial short story, evocative of a Spaghetti Western movie, takes place on “The fifth and smallest planet in the Rigel system, a barren dustball, worth only a small profit to the food co-op that owns it.” Cruel men take charge and the situation is dire. The scene shifts to Rome, and specifically, the Vatican. After being informed of the circumstances, the Pope advises his subordinate to “Send Evangeline.”

(Foreshadowing future ownership disputes, the bottom of the first page of this story has a hand-lettered note: © Charles Dixon, Judith Hunt + Comico.)

Evangeline arrives on the planet in full nun regalia and is initially subservient and docile, as is often the case for comicbook heroes when they maintain in their “secret identity.” The tension soon ratchets up, and she is in full action-movie mode!

At the climax of this short story, Evangeline, with rifle in hand, confronts the cruel antagonist. He looks on in horror and stammers, “You were disguised as a nun!”

Evenhandedly, Evangeline replies: “No disguise. I am a nun.”

The criminal laughs at the absurdity of the situation even as Evangeline shoots him. The last panel of the page shows her praying over his corpse.

Heeding the Call

Evangeline’s first appearance, Primer (a.k.a. Comico Primer) #6 (Feb. 1984). Cover by Judith Hunt.

Sister Act

Publishers were in the habit of producing comics with nuns long before Evangeline, including (left) Charlton’s Catholic Comics (shown is issue #6, from 1946) and (right) Dell’s TV tie-in The Flying Nun (issue #1, from late 1967).

EVANGELINE’S NOVITIATE

Charles Dixon soon became known as Chuck Dixon. As one of the most prolific comic-book writers, Dixon is well known for his work on a wide variety of characters including Batman, the Punisher, and Conan. At this writing, Dixon writes the Levon Cade series of action thrillers and recently published a new novel featuring Conan.

At the time of Evangeline’s creation, Dixon was married to the character’s co-creator, artist Judith Hunt. She enjoyed a relatively brief career in comics, and also worked on licensed series like DC’s Robotech Defenders [see BI #137—ed.] and Marvel’s Conan the King. Hunt and Dixon would split up during the Evangeline series. She left the Evangeline series, although Dixon continued scripting. She would soon leave comics altogether for children’s illustration, most notably Highlight’s “Timbertoes” comic strip.

In a July 2020 interview on the Comic Book Historians podcast, hosted by Alex Grand and Jim Thompson, Chuck Dixon recalled how Evangeline was created.

“I don’t remember the year, sometime in the ’70s, late ’70s,” said Dixon. “It was something that had been kicking around in my mind for a while, and we presented it at a couple of companies. And then this company, Comico, popped up in Norristown, Pennsylvania, which wasn’t that far from where I was living at the time.”

Dixon described the premise. “Well, it’s a futuristic story, a science-fiction story, you know, space opera, a planet-hopping thing. It features Evangeline, who is a nun with the church and she’s sort of a spy for the Vatican.”

Evangeline had her own literary precedent. “I read a series of paperbacks called The Inquisitor,” continued Dixon. “They were written under a pseudonym by Martin Kruse Smith. And they were about basically a James Bond who works for the Vatican. And he has a sort of dispensation to kill, as long as he does penance afterwards. I mean, it was a great series. It’s a great series. It’s in that men’s-adventure paperback genre. But to me, it’s like literature. Each novel was really terrific, if anyone

From the outset, Evangeline employed a small cast of recurring characters:

Evangeline – a stoic beauty, focused on the job at hand. She’s almost a mix of Star Trek’s Mr. Spock and The Terminator’s Sarah Connor. Tough as nails with an intense, purpose-driven push to move forward.

Fans first met Evangeline in full nun habit in Comico Primer #6. During a crisis, she quickly sheds her habit and begins firing her rifle. Seeing this, one incredulous villain assumes she was just pretending to be a nun. She shoots him, emotionlessly, as she explains she is a nun. And after she has killed him, she prays a Latin blessing for his soul.

We learned a little bit of her background in two interlude/flashback tales, and there were teases that there were more youthful adventures to be revealed.

Cardinal Syn – Like Bond’s M or Batman’s Police Commissioner Gordon, Cardinal Syn is Evangeline’s boss in the Catholic hierarchy. Dixon and Hunt don’t present him as a despicable scheming boss. He is sympathetically presented as a flawed man in a flawed system. He’s passionate about the Church, and will go to any lengths to protect the organization and its members. Of course, the absurdity of having to kill for love or use guns for peace is lost on the characters. Like Charlton’s/DC’s the Peacemaker, Cardinal Syn is too much “in the moment” to ever question his tactics or motives.

Johnny Six – We first meet Johnny Six as he reluctantly teams up with the Contessa (one of Evangeline’s frequent disguises) in Comico’s Evangeline #2 aboard about “The Hate Boat.” Johnny Six serves as the audience POV character. He’s enthralled by Evangeline’s beauty but perplexed by her devotion to God and her commitment to abstinence. Evangeline isn’t oblivious to his affections, and she is often kind but firm. It is clear that Johnny Six isn’t the first lovesick man with whom Evangeline must contend.

Aztec Ace is a series about time travel and paradoxes. We could very easily take up the rest of this magazine to fully describe the series, but— hopefully—readers might be encouraged to seek out the issues—or the collected edition—and discover it for themselves.

PENNSYLVANIA, 1984

Writer/creator Doug Moench was interviewed by Bob Greenberger in David Anthony Kraft’s Comics Interview #10 (Apr. 1984). Moench stated, “Aztec Ace comes from an unwillingness on my part— after what happened with Moon Knight and Weirdworld at Marvel—to give away another creation. Anyway, I’ve had the idea for Aztec Ace for a long time now, stored away until the time—ahem—was right.”

Moench kindly spoke with BACK ISSUE : “ Aztec Ace? That was the most self-indulgent thing I ever wrote [laughs]! When I quit Marvel and went over to DC, my phone didn’t stop ringing. I don’t know how these people knew about it, but they did. One of the calls was from Dean Mullaney and Cat Yronwode at Eclipse. They wanted to do something with me and wanted to know what ideas I had. I told them about four or five ideas, including my vague concept about time travel. They liked it but I told them, ‘But that’s the most non-commercial idea. That will be the hardest to sell. It’s really just my excuse to write about all of my interests.’ ‘We’ll do it,’ said Dean, and they offered me more money than DC!

“Did you know that Steranko named the series? He rang me up. I told him what I was working on and I told him about my time travel book. ‘Sounds great,’ he said, ‘What’s it called?’ I read him some of my potential titles and when I got to ‘Aztec Ace’ he said, ‘Stop! That’s the one!’ And I told him, ‘But that’s the one which least describes what the book’s about! The title has nothing to do with the book!’ ‘Doesn’t matter,’ he replied, ‘it’s catchy.’”

TENOCHTITLAN, 1518

Aztec Ace #1 (Mar. 1984) was written by Moench, penciled by Michael Hernandez, inked by Nestor Redondo, colored by Philip DeWalt and Denis McFarling, and lettered by Adam Kubert (!). Therein we are introduced to Ace and Bridget, in the city-state of Tenochtitlan (in what is now Mexico City), in the year 1518. We

Time Is on My Side

From Eclipse Comics and writer Doug Moench, Aztec Ace #1 (Mar. 1984). Cover pencils by Michael Hernandez (Bair) and inks by Thomas Yeates. The “McFarling” in the signature is cover colorist/logo designer Denis McFarling. Unless otherwise noted, art scans illustrating this article are courtesy of Jarrod Buttery.

Time Passages

Imaginative layouts by penciler

Hernandez, inked by Redondo, on pages 34 and 35 of Aztec Ace #1.

Nine Crocodile, and it’s clear that he and Ace have history. Ace makes a break for it and disappears into the city-ship. Circling back, Ace overhears Krok and the fake-Franklin discussing their plan to sabotage the real Franklin’s mission to secure French support for American independence. Ace also bumps into Shakreen and it’s clear that they also have history.

Shakreen is Krok’s wife, and it is implied that this is a recent development. She is also pregnant, and it’s strongly implied that the father of the child may be Ace.

Shakreen helps Ace to escape in her personal Shift-Vehicle. Ace must shut out all thoughts of the two women in his life—the past with Shakreen, and the future with Bridget—in order to stop fake-Franklin’s sabotage mission. He does so by boarding fakeFranklin’s privateer. With history jeopardized, another doxie-glitch manifests as a sea monster, which Ace provokes into attacking the vessel. Fake-Franklin makes a run for his Shift-Vehicle and Ace follows, despatching the Ebonati doppelganger. Real-Franklin’s mission is successful and America wins the Revolutionary War.

CAIRO, 2523 BCE

Aztec Ace #3 (June 1984) finds Ace and Bridget still separated. In the Shift-Vehicle that he stole from fake-Franklin, Ace discovers an Ebonati plot to raid Cheops’ legacy—and so travels to ancient Egypt. Meanwhile, after finding one frozen slug, Bridget and Head manage to extract enough slime to aim for warmer climes. This third issue also brought a change in artists. Moench told Greenberger that the book’s original tentative title was Captain Wow “When I ran Captain Wow through my head, the visuals were always an amalgam of Ploog and Holmes, Wrightson and Corben. When it came time to do it, however, I knew those guys were all involved with their own things. But then a lightbulb went on over my head and I remembered my best collaborations. Almost every one of them was with a new, young artist—someone who was yet to become jaded or burnt out—guys who were fresh, vigorous, enthusiastic, ready to conquer worlds. Gulacy, Zeck, Mayerik, Ploog, Gene Day, and so on. Ergo, let’s go for a young guy on Aztec Ace, someone who’s already good and who’s obviously going to get better as we go along. Unfortunately—

“He’s the ultimate American hero, an indestructible symbol of hope and courage for an entire nation, a one-man army standing tall for Freedom, Justice, and the American Way—but what about truth? When reporter Dennis Hough is assigned to cover a story about his boyhood hero, he begins to see the cracks in the legend. Does The American have feet of clay? Or is he himself a victim of a larger conspiracy?”

That’s how the back cover blurb summed it up on Dark Horse Comics’ 2005 trade volume collecting the original eight-issue run of The American

Here’s how Don Markstein’s Toonpedia explained The American: “Patriotic-style superheroes, all decked out in red, white, and blue, have been part of the U.S. comic-book scene ever since MLJ Comics introduced The Shield in 1939. From Marvel Comics’ Captain America (1941) to DC’s Steel, The Indestructible Man (1978), all had many points in common, among which was the fact that their patriotism was a simple, straightforward type, unequivocal support of the U.S. government in all its endeavors. It wasn’t until the 1980s that more nuanced forms of patriotism came into vogue, and it became possible to do ‘patriotic’ heroes along the lines of American Flagg and this one… writer Mark Verheiden’s succinctly named The American.”

Verheiden would reminisce in the introduction to the collected volume: “The American was created out of real love for the comics medium, because I’ve always loved comics. I’m talking completely, unapologetically, and with fierce devotion. I collected them as a kid, debated them endlessly in amateur press associations (APAs) as a young adult, and then, well, gave up on them as a post-graduate film career beckoned. The late ’70s/early ’80s weren’t exactly ‘prime time’ for mainstream comics, and my passion for the form may have petered out entirely if not a happy confluence of events.

“To wit, two old Oregon friends, Mike Richardson and Randy Stradley, decided to start a comic-book company [see BACK ISSUE #22—ed.]. They were going to call it Dark Horse, and to the derisive chuckles of many, their mad master plan was to ‘publish good comics’…. I attended the annual San Diego Comic Convention back in 1986. It was a blast to bask in the creative glow of fans and professionals, and it was also a chance to hear out Mike and Randy’s plans for Dark Horse, which ended with the magic words, ‘Would you like to write something for us?’”

The result, as you’re about to read, was The American, from Verheiden and artist Chris Warner, premiering with issue #1 (Aug. 1987). The original series concluded with The American #8 (Feb. 1989).

Mark Verheiden (born March 26, 1956) is known more for his television and movie work than he is as a comic-book writer. For TV and film, Mark has a long list of involvement including as a writer and co-executive producer on the second incarnation of Battlestar Galactica and the prequel, Caprica , and as a staff writer and consulting producer for Heroes. Mark wrote the movies Timecop and The Mask, and worked on the Timecop TV series, Smallville, Falling Skies, Constantine, Daredevil, Ash vs. the Evil Dead , and Swamp Thing , among others. His first comics work was Dark Horse’s The American , which would lead to extensive work on Dark Horse’s Aliens and Predator series. They ended up naming a character after Mark in the 2004 Alien vs. Predator movie. At DC, Mark wrote Superman stories for Action Comics Weekly, the Smallville TV tie-in series, and the Phantom 12-issue maxiseries. At Marvel, Mark wrote the 12-issue Stalkers for the Epic line.

Chris Warner (born 1955) is a triple threat at Dark Horse Comics as a writer, artist, and editor. At Dark Horse he’s worked on Predator, Alien vs. Predator, Comics’ Greatest World, and Barb Wire. At Marvel, he worked on Alien Legion, Moon Knight, Doctor Strange, and Strange Tales. At DC, Chris penciled Batman #408 with writer Max Allan Collins. I had a chance to talk with Mark and Chris via email about The American …

Stephan Friedt by Stephan FriedtA Real American Hero

Original artwork by Chris Warner for the cover of the 1988 The American trade paperback, which reprinted issues #1–4 of the Dark Horse Comics series. Courtesy of Heritage Auctions (www.ha.com).

Standing Up for America

Warner’s covers to The American #1 (Aug. 1987) through 3 (Dec. 1987), also featuring supporting characters Dennis Hough (#2) and Kid America (#3).

STEPHAN FRIEDT: How did you two get together as a team? What was your collaboration like? Full, detailed scripts? Open-ended directions?

MARK VERHEIDEN: As I recollect (a caveat that should apply to all of this!), I attended the 1986 San Diego Comic-Con and spent an evening in the Dark Horse suite (not as fancy as it sounds, back then), where I talked with old buddies Randy Stradley (former roommate, later a Dark Horse exec for many years), Chris, publisher Mike Richardson, and others, and I believe Randy and/or Mike invited me to write something for them. On the drive back to Los Angeles with my then-girlfriend/soon-to-be-wife Sonja, I spewed out most of the idea for The American. I don’t recall if I wrote a treatment or pitch document, but fairly quickly I wrote the first issue and delivered it to Dark Horse, and Mike and Randy decided to publish it.

We looked for an artist for a while (I recall seeing samples from a very young Rob Liefeld!), until Chris Warner stepped in and took the job. Of course, he was amazing, Chris is hands down one of the best action comic artists ever. I think he liked the script, but that’s for him to say. And I wrote full, overdetailed scripts, taking my cues from what I’d heard about Alan Moore’s script style.

CHRIS WARNER: Around the time The American surfaced at Dark Horse, I was in the process of becoming the main artist on Batman . I had high hopes for that gig, but it rapidly went sour, and I was very demoralized by the situation. I read the first script of The American and saw that it was the kind of book I really wanted to be drawing. The script was so fully realized, a major departure from the loose, plot-style approach I was used to at Marvel. I ended up getting fired from Batman, deservedly, but the American gig was still open, so I got the part I really wanted. Also, I’d known Mark since high school, so it was fun to be working with an old pal. Sometimes things work out for the better.

FRIEDT: What was the inspiration for your work on The American?

VERHEIDEN: Well, obviously it appeared to be sort of a riff on the Captain America/Fighting American–type comic-book heroes, but it was really inspired by movies like Rambo 2 and the then-popular Chuck Norris Missing in Action films. Movies where the oneman-army hero re-fought old wars and of course “won.” I thought they were silly and ripe for satire. Also, this was the time of the Iran/Contra debacle, and so my general distrust of government and military leaders (not the soldiers) was pretty high.

[

Editor’s note: Mercy St. Clair is a resilient bounty hunter—a “trekker” —in a futuristic society in writer/artist Ron Randall’s creator-owned science-fiction comic book, Trekker . Trekker first bowed in a serial that started in Dark Horse Presents #4 (Jan. 1987), followed by Trekker miniseries, specials, and further serializations. Randall’s seminal sci-fi saga was collected in The Trekker Omnibus (2013) and is serialized online at Trekkercomic.com.

In the interview that follows, Trekker’s creator speaks with BACK ISSUE interviewer Cecil Disharoon about the origins and development of the character and series.]

CECIL DISHAROON: How did Trekker first come to life in your mind? I wonder… That first drawing of her, seen in your Trekker Omnibus —was there a spark-impulse that called, “Hey, Ron, make a retro futuristic world for her”? Or was this sketch the culmination of a search for a lead character for such a world? Did you already want to tell this kind of sto ry, and just didn’t have the lead character?

RON RANDALL: It was probably more the latter, I think. I started off with this blank slate of what would I choose, if I were to create my sort of my dream project—the story that I would like to tell the most—what would that look like?

I started to think of some of the elements. On that conceptual level, I knew I wanted it to be a science-fiction story, because I had the opportunity to work on a couple of sciencefiction things in comics. When I worked on those, I knew I was lucky because there weren’t a lot of science-fiction comics back then, and I really enjoyed that, because I’ve loved science fiction ever since I was a kid.

When I had a chance to try to emulate my some of my art heroes—Wally Wood, Al Williamson, Flash Gordon by Alex Raymond, that kind of stuff—well, I jumped at the chance, so I knew the basic genre pretty quickly. And I knew, because I came up learning from and working with Joe Kubert, that sort of action-adventure story that had a visceral appeal to it; I knew that was my wheelhouse, too, as opposed to something really sort of esoteric—an abstract piece.

So, action-adventure. And I thought, “If it has a character who can roam to a lot of different settings and situations, that brings a lot of environments, a lot of variety, into the stories—good for me, you know, as a creator, to have new meat to chew on from one story to the next.”

So, a bounty hunter. There’s the old Wild West sort of thing about an individual character out there, and a variety of different journeys that that character can go on. That became a piece of it, too.

DISHAROON: And her gender?

RANDALL: I also knew early on I wanted a female lead character, because that wasn’t happening in comics very much.

I had a chance to do the backup series in the Warlord comic book at DC for a while a couple years before: The Barren Earth, written by Gary Cohn, who is a writer that isn’t as well-known as I think he should be. Gary dreamed up the basic concept, and he and I developed it.

Gary’s vision was much more of an Edgar Rice Burroughs–sort of version of sci-fi, but it had a female lead character. It was so cool to have the female character not be the sidekick, or the love interest, or something like that. She was the central character: she drove the narrative, and that was such a fresh thing to do in comics, [compared to what] I had experienced up until that point. It opens up a different sort of emotional landscape, that you can have your main character explore, than you could generally do with the male character. [Editor’s note: See BACK ISSUE #137 for a Cohn/Randall Pro2Pro interview about their Barren Earth collaboration.]

Have Mercy!

All those elements were there at the beginning, when I was coming up with Trekker.

So, I’d been on a couple of walks, letting some of these things ruminate, and then I said, “Now, it’s time to start putting some stuff down on paper.” I just sort of started pushing the pencil around on the page, gesturing in a rough pose for a character that would try to have a certain sense of attitude.

I knew that I wanted a character who dressed appropriately for her job, so there would be a certain amount of gear, pads, straps, and weaponry on her, so that she would look like an action character— like a bounty hunter, as opposed to looking like a chorus girl or something.

DISHAROON: Tell me about thinking up her stories the process of choosing which to tell, and in which order should you create them? How did you decide which episodes were appropriate to the characterization you’ve developed? Or did those aspects “pop out” about Mercy St. Clair as you pondered where in her world she was going?

RANDALL: Part of the impetus, when I was coming up with Trekker, was: if I was going to do a story of my own, it’d have to be about something more than just the level that the 12-year-old me loves: you know, swamp monsters and spaceships crash landing on barren foreign planets and raw gun fights—all those cool “swashbuckler-y” adventure resources. I love that stuff, but I knew, for a series to hold my interest, and be able to continue to inspire me to put all the work into it that you have to do to create a comic book, one after another and stuff, there had to be in some way more substance to it than just, “Oh, that’s a cool story idea,” you know? It had to be about something.

The thing that you mentioned there is, it’s this young woman’s gradual evolution: as a human being, as a character, her self-discovery. Sort of, “If she can make it this year, she can survive the trip.” And part of it was about the role of violence, and the uses that we put it to, and whether there are alternatives.

I don’t have answers, I just ask questions and let the stories take the characters where the story takes them. Then I let the readers and myself included sort of draw our own conclusions from the experiences that we have with those characters, because I came to feel, from very early on: If you’re writing a story and you definitely have like, “I’m gonna deliver the message of this; the moral of the story is this”—that’s not art; to me, that’s propaganda. That’s like writing a persuasive essay. I explore these characters and the richness and the complexity of the complexity of the world and characters.

I like to say: Trekker started as a black-&-white comic, and that’s how Mercy saw things, a black&-white view of the world: “I shoot people, I get paid.” On an elemental level, that’s how simple she’d like things. She starts off very much closedin. She has relationships with men—like Paul, a good guy, a cop—but it’s sort of at arm’s length. She’s always got to be in control.

DISHAROON: Even with allies like the gangster Lazmuzi, and pacifist Rigel agent, Jason Bolt. Her uncle Alex on the force feeds her tips, but she is independent.

RANDALL: From the very first eight-page chapter, we see Mercy out there being a badass and shooting up the bad guys. Then she goes back to her crappy little apartment that she lives in in the middle of the city, and inside the apartment, there’s this scruffy old pet domesticated fox that she has, named Scuff.

I wanted to include that because there was no reason that an implacable killing machine bounty hunter would have a pet fox. The only reason: there is more to her. Right off the bat, there’s more going on underneath the surface than Mercy is aware of, or even cares to.

DISHAROON: She still wants to nurture something even though her career is no-nonsense: fighting for her life, outnumbered, intricacies, and abilities of her target bounties, possibly fighting to the death, even.

RANDALL: Yeah, and that’s the stuff that gets me the most excited about telling the stories!

Deal Me In?

Trekker makes a dramatic debut in her premiere story in Dark Horse Presents #4. Story and art by Ron Randall. Trekker © Ron Randall.

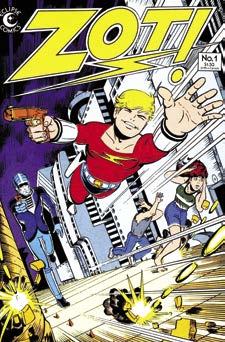

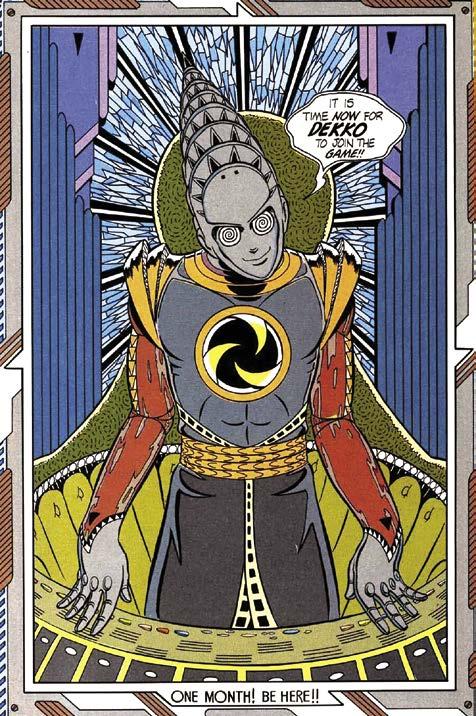

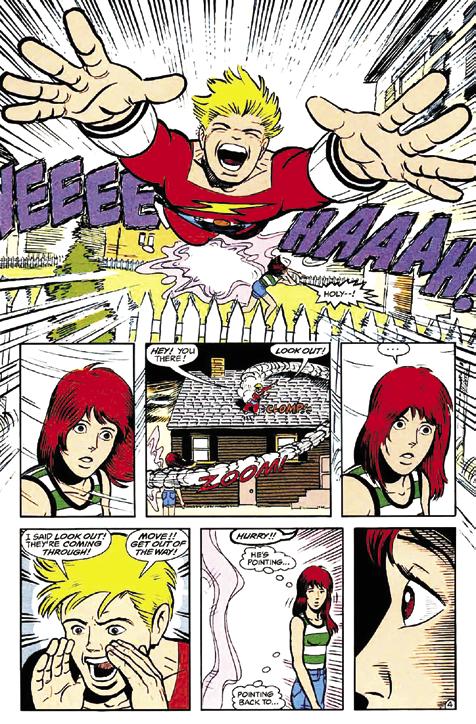

Created by writer/artist Scott McCloud, Zot! tells the story of Zachary T. Paleozogt, who lives in a utopian, futuristic Earth that is forever in the year 1965, and Jenny Weaver, who exists in a decidedly more troubled Earth of the mid-1980s.

This story of two dimensionally crossed friends (and potential lovers) takes place over the course of Zot! ’s 36-issue Eclipse Comics run, which is uniquely divided into three eras: the first ten color issues (Apr. 1984–July 1985), the “Heroes and Villains” arc that runs from issues #11–27 (Jan. 1987–June 1989), and “The Earth Stories,” which close out the series with issues #28–36 (Sept. 1989–July 1991).

To learn more about the behind-the-scenes stories of these groundbreaking tales, I am talking exclusively in this piece with Scott, as well as his old friend Kurt Busiek, artistic collaborators Chuck Austen, Matt Feazell, and Todd Klein, and editor Catherine “Cat” Yronwode.

Meet Our Boy Hero

It’s Zachary T. Paleozogt— a.k.a. the much-easier-toremember Zot! Detail from Scott McCloud’s cover to the collected edition The Original Zot: Book One Zot! © Silver Linings.

– Tom Powers