13 minute read

Liverpool to Hamburg

The Who

From a working-class area called Shepherd’s Bush emerged a band that became one of rock’s most enduring and influential.

As musicians, each member of the Who was unique and inimitable: singer Roger Daltrey (born 1944), guitarist Pete Townshend (born 1945), bassist John Entwistle (1944-2002) and drummer Keith Moon (1946-1978), all London boys. When performing live, Townshend, Entwistle and Moon would go off on individual flights of fancy, but they were always playing the same song.

In the late 1950s, Daltrey, Townshend and Entwistle were each attending Acton County Grammar School, a boys’ school.

“I suppose our town was not very dissimilar to, like, the Bronx,” Daltrey said of Shepherd’s Bush when we spoke in 1998. “We were not financially wealthy, but we were incredibly rich.”

Like many British musicians of his generation, Townshend came from a musical family. His dad, Clifford, recorded as “Cliff Townsend (alternate spelling intended) and His Singing Saxophone.”

Daltrey formed a skiffle group, the Detours, with a guitar he made in a sheet metal factory at which he worked.

“I started making my own guitar when I was 11 to 12 years old,” Daltrey said. “By the time I was 12, 13 years old, we were playing what was the equivalent of your early American folk songs, which were brought to us by a guy called Lonnie Donegan.”

BY 1962, TOWNSHEND AND ENTWISTLE WERE ALSO in the Detours. Daltrey recalled that the band was playing the Oldfield Hotel in Greenford when they were approached by Moon, who was wearing orange hair due to a peroxide mishap. (He was a huge Beach Boys fan.) Moon told Daltrey: “I hear you’re looking for a drummer, and I’m much better than the one you’ve got.”

“The first time I met Keith,” Entwistle told me in 1999, “he was like a little gingerbread man. He had ginger hair on a brown suit, a brown shirt with brown shoes and one of those fake orange tans.”

Moon joined the Detours in April 1964. The clownish “Moonie” completed the equation. His thrashing, unpredictable drumming was the perfect complement to Entwistle’s virtuosity, Townshend’s power chords, and Daltrey’s macho front-man style.

“He did kind of blow us away,” Entwistle said.

“Actually, the first gig that we did (with Moon) was someone’s wedding, believe it or not. That was the first time he blew us away. Because he actually tied his drums to this pillar on the side of the stage, so he wouldn’t fall over when he played the solo! And the drums were, like, heaving out, sort of, at about 45 degrees, held together by this big reel of rope.”

MEANWHILE, TWO ASPIRING FILMMAKERS, CHRIS Stamp and Kit Lambert, were on the lookout for a band to make a film about. By then, the Detours had renamed themselves the High Numbers, and were identifying as a “mod” band. In those days, English youths often identified as being either a “mod” (fashion conscious) or a “rocker” (street tough). Stamp and Lambert caught a High Numbers show and decided to manage the group. The band underwent another name change — “the Who” beat out “the Hair,” thankfully — just as England’s music scene was blowing up in 1963. The Who stumbled onto a publicity hook in 1964, when

Townshend smashed his guitar during a gig at the Railway

Hotel Harrow & Wealdstone, in Harrow. (As an art student,

Townshend saw a presentation by artist Gustav Metzger, founder of the “auto-destructive” art movement. Townshend interpolated Metzger’s concept into his guitar-smashing bit.)

This became a calling card for the Who. Another Townshend trademark: his “windmill”-style guitar strumming technique. “We were one of a million bands,” Daltrey said. “How do we get noticed? It was just one of those lucky things that happened. A lucky break, to coin a phrase, which got us noticed.”

The band’s debut single, “I Can’t Explain” (#8 in the U.K.), was helped immensely by the English TV show “Ready Steady

Go!” but failed to crack the Top 40 in the United States.

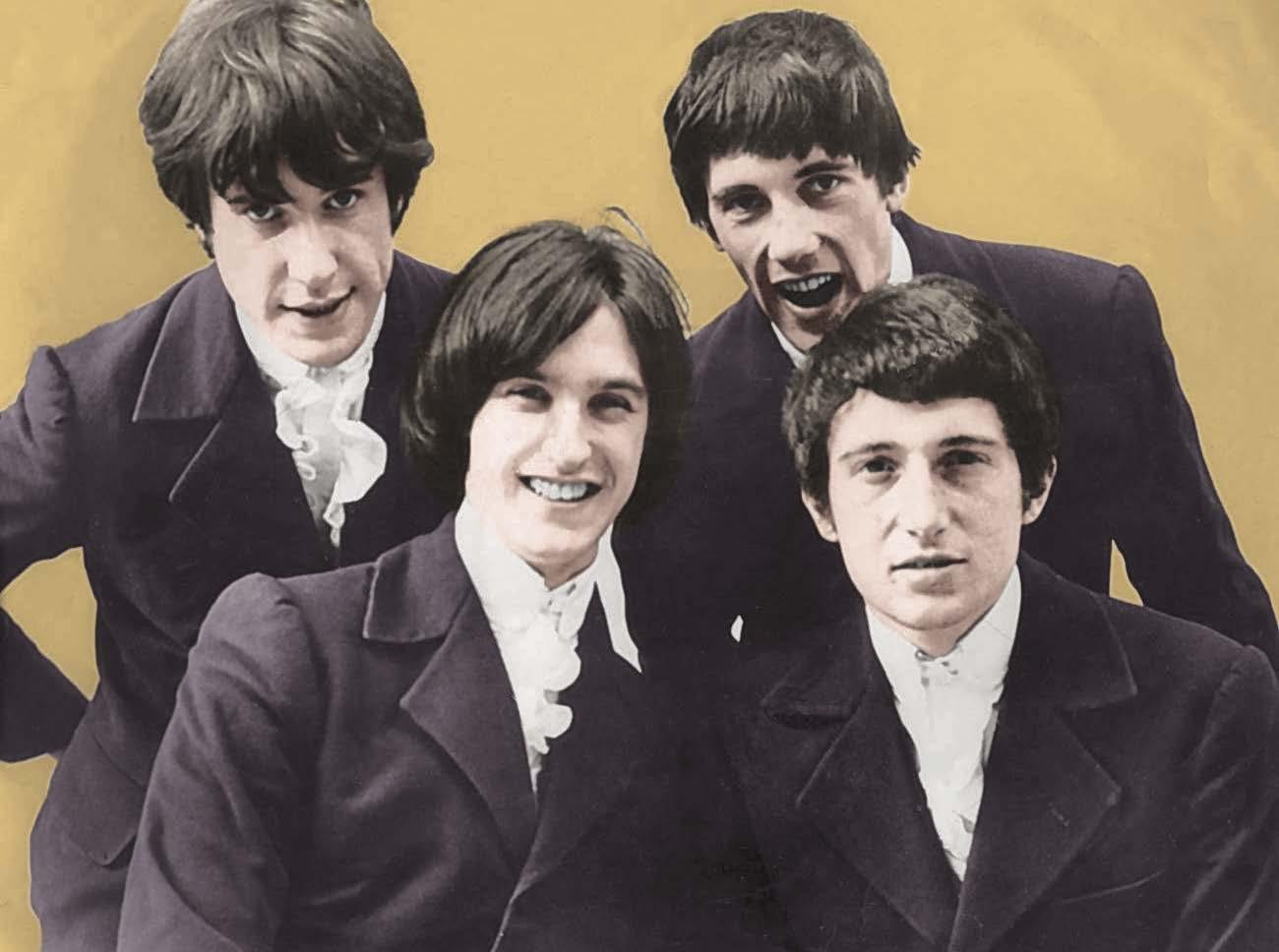

The Kinks

You really got them! The Kinks, from left: Ray Davies, Dave Davies, Mick Avory and Pete Quaife. Colorized publicity photo

Long before the Gallagher brothers of Oasis fought over their first toy, there were the Davies brothers: singer Ray and guitarist Dave.

As founders of the Kinks, Ray and Dave forged one of the most tempestuous relationships in rock. The Kinks formed in 1963, in the Davies’ home turf of Muswell Hill in North London.

Between 1964 and ’66, the Kinks scored eight Top 40 hits, including “You Really Got Me” (#7), “All Day and All of the Night” (#7) and “Tired of Waiting For You” (#6). The band’s sound was then raw, and the lyrics (from main songwriter Ray) were clever. Dave was an early exponent of guitar distortion.

TWO EVENTS LEFT THEIR MARK ON THE EARLY Kinks. Prior to charting in 1964, the band was summoned to open for the Beatles in Bournemouth. In Ray Davies’ telling, when he shook John Lennon’s hand backstage, Lennon tersely reminded him that the Kinks were only there as a “warm-up.” This slight made the Kinks work all the harder on stage. “You Really Got Me” — which was yet to be recorded — drew a rousing response from an audience that was there to see the Beatles.

The following year, the Kinks had embarked on their debut American tour. But a snowballing series of incidents — including an onstage tussle among band members, and the band threatening to cancel a show over payment — caused the Kinks to be banned from performing in America (by the powerful American Federation of Musicians) for four crucial years, through 1969.

Ray has intimated that retribution against the Kinks was a factor. Asked what caused the ban in a 2015 TV interview, he cryptically cited “bad management, bad luck, and bad behavior.”

But the Kinks did not crawl home to die. The band eventually resumed touring and recording through distinct phases: concept albums (“Preservation Act I”); a return to roots (“Sleepwalker”); and as stadium rockers (“Low Budget”). Considering the ambitious arrangements of later Kinks material, I asked Dave Davies if he felt songs like “You Really Got Me” and “All Day and All of the Night,” with their rawness and directness, are more evocative.

“Actually, I think you can say a lot more through passion, sometimes, than you can through sophistication,” he allowed.

“Passion can be more sophisticated than trying to explain and analyze things. That’s what communicates: a feeling. That’s kind of been my job in a way, to express ideas in feelings and emotions. That’s what rock’n’roll is. Listening to those early Buddy Holly and Howlin’ Wolf records, and all those influences, singing about pain and their girlfriends and all of this — but there’s something else happening. There’s this energy. This expression.”

BEST-KNOWN LINEUP: Singer Ray Davies (born 1944); guitarist Dave Davies (born 1947); bassist Pete Quaife (1943-2010); drummer Mick Avory (born 1944). All were born in London except Quaife, who was born in Devon.

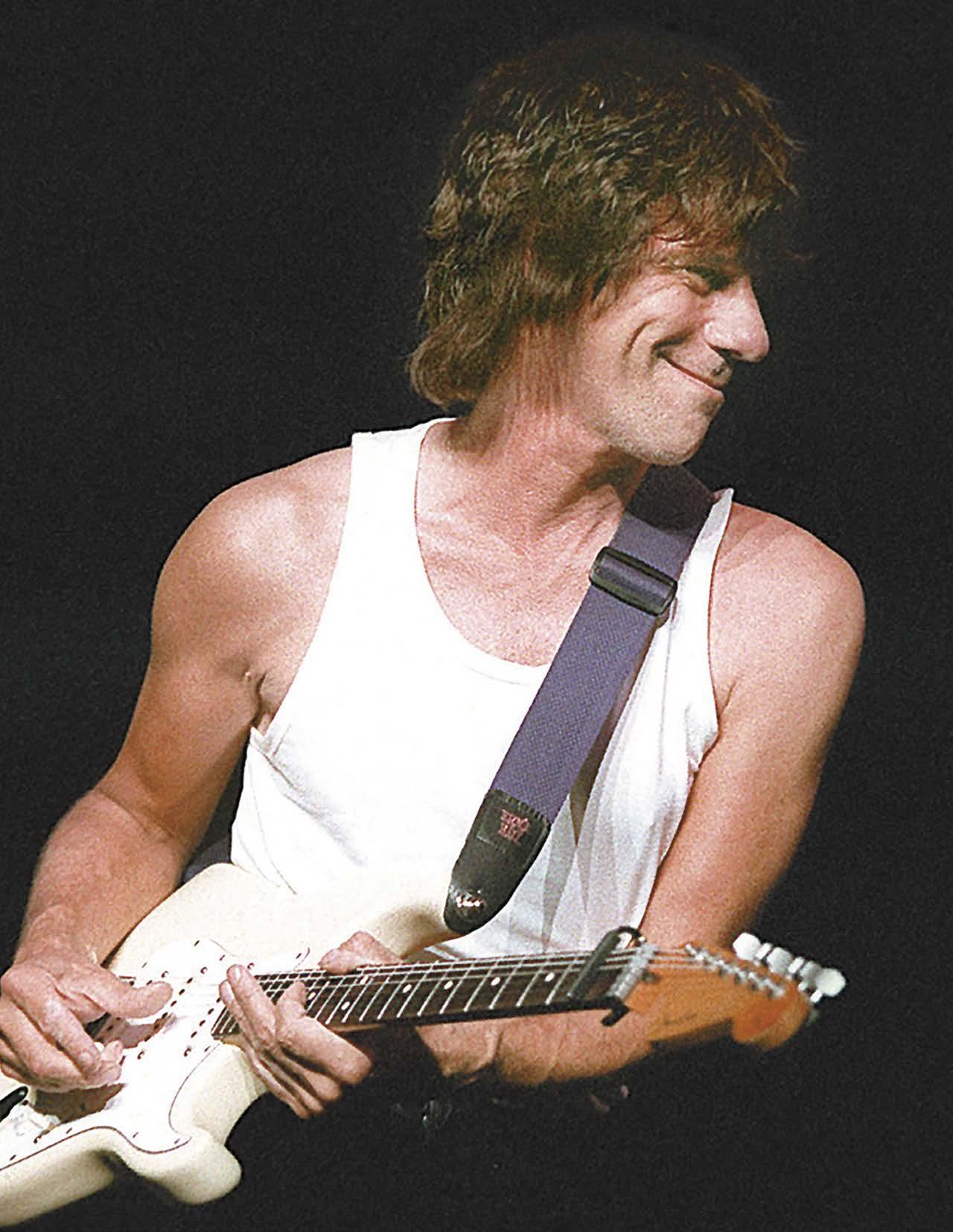

Jeff Beck Beck

Jeff Beck’s sister, Annetta, heard tell of a boy in the neighborhood who, like her brother, was obsessed with playing guitar.

Without having met Jimmy Page, Annetta Beck decided Jeff and he should be introduced. She marched up to the Page homestead with her brother in tow, and knocked on the door. The first meeting of Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page, at age 13 or 14, became one of those uncanny crossroads in rock.

Page recalled that Beck brought along a homemade guitar, and had been learning songs by listening to records. That day, these kindred spirits forged a friendship that would last for decades, with careers that would occasionally intertwine.

OVER THE NEXT FEW YEARS, BECK JOINED A series of bands and got as much stage experience as he could — not that his equipment was the greatest.

“Golly, every day was a year back then, you know,” Beck told me in 2011.

“I don’t recall owning an amplifier. It was always a sob story to the band. I used to plug into a tape recorder or a radio. My first amp was a 5-watt Selmer. It probably couldn’t be heard beyond the first row! Then I moved onto an El Pico, which was pretty loud. The El Pico stood up to a lot of abuse, and I’m talking about booze, getting kicked, cigarette burns. I blew that up. Then I got a Vox Twin, which sounded good, and then a Vox Super Beetle. Then I moved onto Marshalls.”

Recalled Beck of the first time he ever recorded: “We were petrified. It was only a demo, but we treated it as if we were making the most amazing record of all time. We did one song; we were only allowed to do one song for the fee we were paying. So we did two mixes, one with echo and one without. I took the acetate home and played it over and over.”

Beck steadily built his career, and by 1965, had played on a few professionally released recordings (including one from Screaming Lord Sutch). Meanwhile, his old buddy Page emerged as a highly sought session guitarist.

IN THE MIDST OF THIS, THE YARDBIRDS WERE looking to hire a new guitarist following the departure of Eric Clapton. They invited Page to join their group, but at the time, he was focused on becoming a record producer.

“Jimmy was a real leaning post for me, because he was always in work, I remember,” Beck recalled.

“I used to go and see Jimmy as often as I could, because I had a car, at least. So I was always bugging him at his house.

“One day, he played me this live Yardbirds album. He said, ‘What do you think?’ He played ‘Five Long Years,’ which is a blues. One of Eric’s best solos. And I said, ‘Wow, this guy’s great.’ Jimmy said, ‘Uh, how would you feel about replacing him if he left the band?’ ‘I dunno about that.’ Because I already had a band which was doing really well in the local area — Richmond and Kingston area.” Beck demurred without giving a firm no.

“And then the next thing that happened was, I’ve got a guy standing in front of me at one of our gigs,” he said.

“This guy was acting on Jimmy’s recommendation. So I obviously must’ve appeared to Jim — at the time that he asked me to join the Yardbirds — like I was half-interested. Mind you, he had rejected the offer, because he wanted to stay earning money,” Beck added with a laugh. “He didn’t want to ditch everything he’d built up, to go on the road with a band that was not really widely known at that time.”

Beck, as rock history tells us, indeed joined the Yardbirds in 1965. “And the rest is greased lightning,” he said. “Everything happened. They had a hit record (‘Heart Full of Soul’) just after I joined. And then the tours of America came. We did two big tours. I say ‘big’ tours; to us they were big, because we’d never been outside South London.”

SURPRISINGLY, PAGE JOINED the Yardbirds as a “temporary” bassist the following year. Page would eventually slide over to guitar, and the Beck-Page lineup of the Yardbirds became famous for its two-pronged guitar approach. “Well, it was unforeseen that Paul Samwell-Smith was going to leave; that was the bass player,” Beck recalled. “He played a huge part. I mean, he had a really wild, big bass sound. He used to play four-string chords on the bass, and just cause all kinds of earthquake sounds. Without that, the band wasn’t really the same band. “And Jimmy, bless his cotton socks, he didn’t really play much bass. But it was my design to get him on doublelead. I promised, ‘If you come in this band, you’ll be on guitar before you know it.’And poor old Chris (Dreja) was kind of duped into playing bass. It wasn’t very good. Jimmy wasn’t settled in, because he’d only just swapped over onto lead, and Chris hated playing bass, as I recall. You know, you don’t just switch from rhythm guitar to bass easily.”

Beck intimated that this situation led to his parting ways with the band (though he couldn’t say if he quit or was fired).

“Really, there was no other solution,” Beck said.

“Because Chris was one of the founding members. And I was an employee. And I remained an employee of the band until I left — or was booted out. I can’t remember what happened in ’67, I think it was.”

Next up for Beck was the Jeff Beck Group, the earliest lineup of which featured relative unknowns Rod Stewart and Ron Wood. But Beck found a lasting niche with the instrumental jazz-rock albums “Blow by Blow” (1975) and “Wired” (1976), which were recorded by — to bring the whole thing full circle — Beatles producer George Martin.

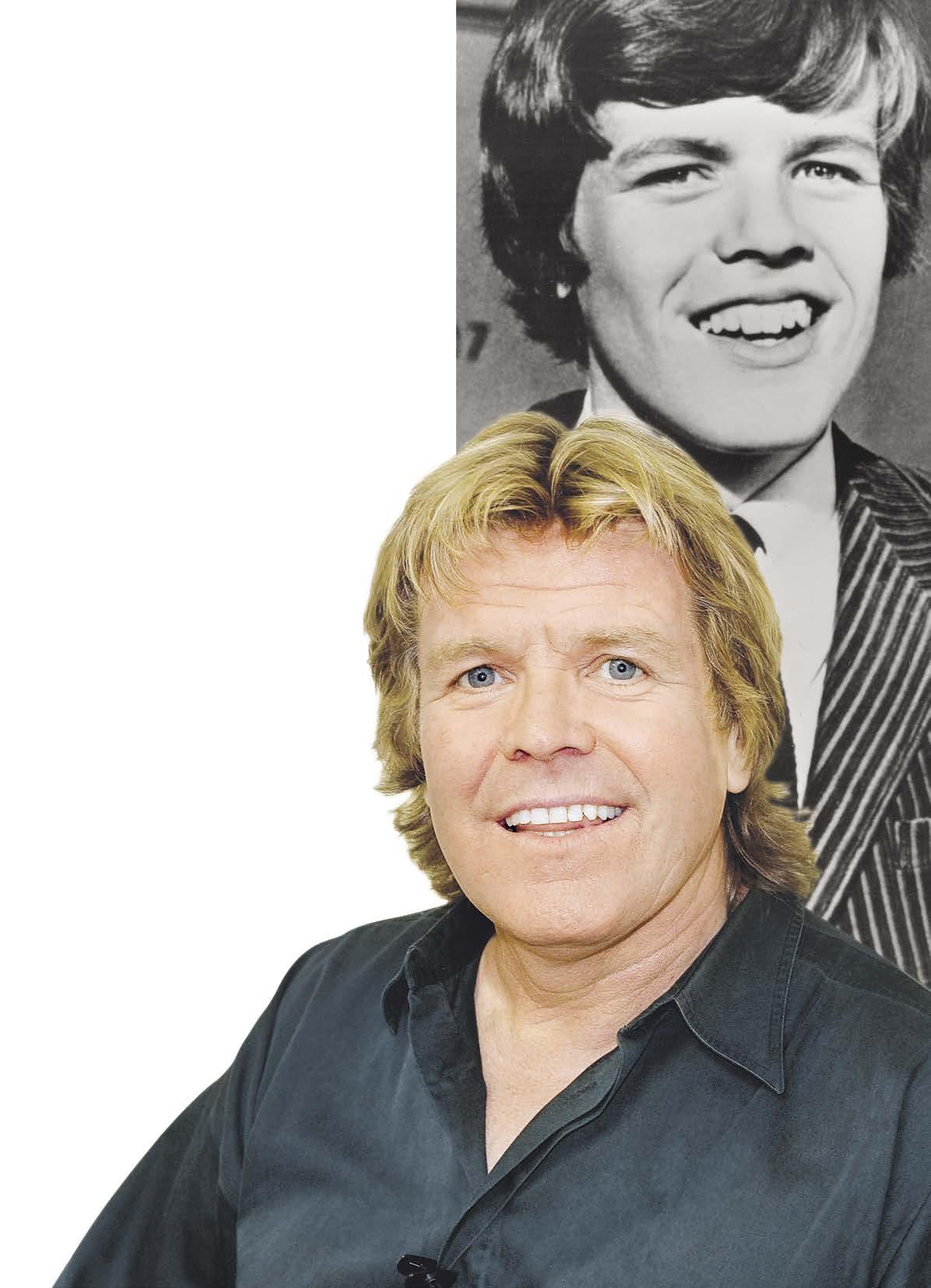

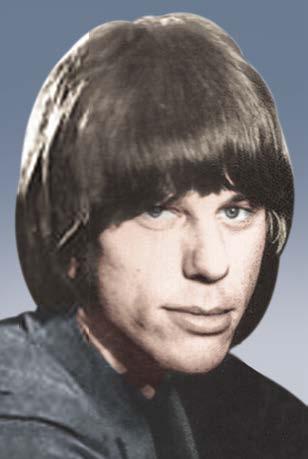

In the bowl-cut 1960s. Opposite: Beck and Strat onstage in 1999.

Publicity photo; 1999 photo by Kathy Voglesong

Peter Noone

Something good

AT SIX OR SEVEN YEARS YOUNGER THAN MANY of his contemporaries, Peter Noone was the antithesis of the rock front man. His comically large front teeth — which Noone proudly didn’t have “fixed” — made him more teddy bear than Teddy Boy.

Noone had already achieved fame as a child actor, but his first love was rock’n’roll. He studied (and occasionally joined) bands that played in clubs. One night, Noone filled in for the lead singer of a band called the Heartbeats. This led to a new group with a most unlikely name. I spoke with the singer in 2003 and 2011.

Q: You were a child star in England. How did your childhood pave the way for the musical career that followed? NOONE: It’s all connected. All of show business is connected. I’m lucky that I’ve done all these other things. It started out that my dad was a sort of almost-famous musician. You know, he almost was famous. He was a good trombone player. I think he wanted to make sure I was a good musician, so he sent me to a school of music. At this class at my school — St. Bede’s Jesuit College For Boys — I was better than the teacher at music. He was a really good priest, you know, because there are lots of those. He said, “You’re better at this than me. You should go to college.” Q: How old were you at the time? NOONE: I think I was 13. He signed me up for the Manchester College of Music when I was 13 instead of 18. They threw me into this class of all these geniuses who made me look like an idiot. I just didn’t know as much as they did. But because I was so afraid, I joined every class. And the only class I liked was the room where the people were playing the Chuck Berry songs. They were all 18-year-olds with beards, you know? I just watched them for a while.

I got into the elocution class. My dad thought it would be important — if I ever was gonna be in show business or any business — to speak properly. Because none of us did that. We all had these terrible accents. I’ve still got mine. It was like a thrown-in class. I did it at night. It wasn’t fulltime. I still had to do my work. You go to a school of music, you’re with musicians. My life just changed. I got on all these TV shows. I got my first acting job because I could play the piano.

“Every day was a new adventure,” said Peter Noone (shown in 2005).