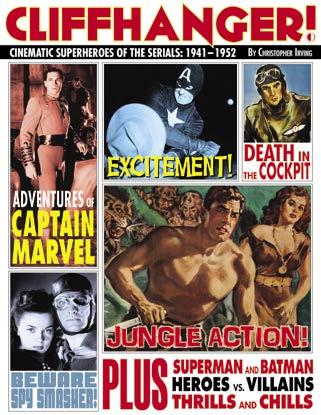

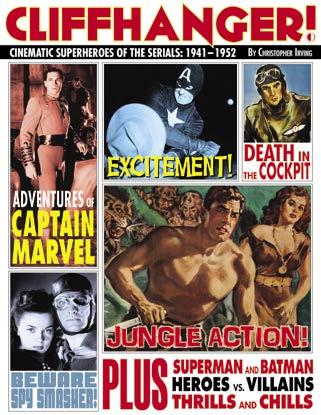

JUNGLE ACTION! MARVEL SPY SMASHER! BEWARE ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN EXCITEMENT! KILLER ROBOTS PLUS SUPERMAN AND BATMAN HEROES VS. VILLAINS THRILLS AND CHILLS CLIFFHANGER! CINEMATIC SUPERHEROES OF THE SERIALS: 1941–1952 by Christopher irving

Written

and

Edited by Christopher Irving

Front cover design by Michael Kronenberg

Book design by Richard Fowlks

Proofreading by Kevin Sharp

TwoMorrows Publishing

10407 Bedfordtown Dr Raleigh, North Carolina 27614

www.twomorrows.com

ISBN: 978-1-60549-119-6

First Printing, March 2023

Printed in China

CLIFFHANGER! Cinematic Superheroes of the Serials, 1941-1952

©2023 Christopher Irving and TwoMorrows Publishing. All rights reserved. No portion of this publication, except for limited review use, may be reproduced in any manner without express permission. All quotes and image reproductions are © the respective owners, and are used here for historical presentation, journalistic commentary, and scholarly analysis.

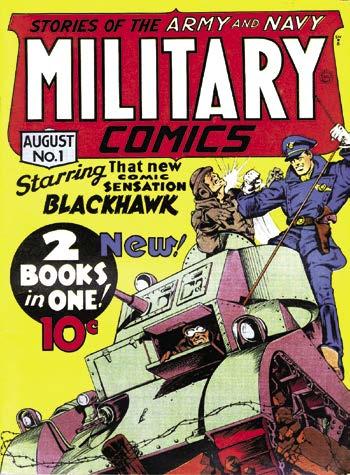

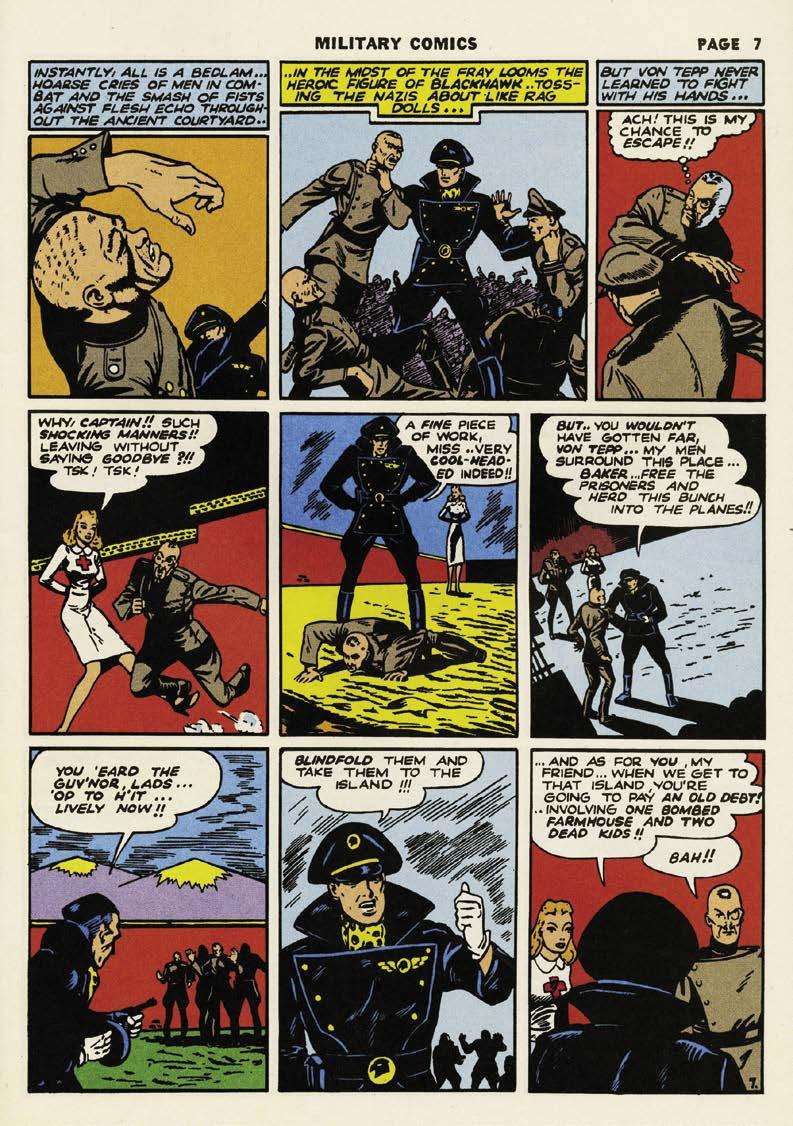

Batman, Robin, Alfred, Joker, Shining Knight, Blackhawk, Military Comics, Superman, Hop Harrigan, Shazam, Spy Smasher, New Fun, All-American Comics, Congo Bill, The Vigilante, Real Fact Comics, Bulletman, Superman and the Mole Men, The Adventures of Superman, Lois Lane, Jor-El, Krypton, Clark Kent, Jimmy Olsen, Perry White, Batgirl, Dr. Occult, Watchmen, and all other DC Comics characters and logos are TM & © DC Entertainment.

Superman: The Movie and all logos are TM & © Warner Discovery. The Spirit and all related characters and logos are TM & © Will Eisner Estate. Funnyman and all related characters and logos are TM & © Siegel and Shuster heirs and all respective copyright holders. Captain America, The Avengers, Iron Man, and all other Marvel Comics characters and logos are TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. Young Romance and all other characters and logos are TM & © the Estate of Joseph H. Simon and Estate of Jack Kirby. The Flying Irishman and all related logos are TM & © RKP Pictures LLC and/or any respective copyright holders. Flash Gordon, Ming the Merciless, Dale Arden, Secret Agent X-9, The Phantom, Jungle Jim, and all related characters and logos are TM & © King Features Syndicate. Dick Tracy and all other Tribune characters and logos are TM & © Tribune Content Agency. Buck Rogers and all related characters and logos are TM & © John F. Dille heirs and/or respective copyright owner. Doc Savage, The Shadow, and all related characters and logos are TM & © Street & Smith. Coca-Cola and all related logos are TM & © Coca-Cola Company. It Happened One Night, the Columbia title and all related logos are TM & © Columbia Pictures. The Mummy’s Hand, Dracula’s Daughter, and all other Universal characters and logos are TM & © Universal Pictures. Pep and all other logos are TM & © Kellogg’s.

Select stills from Republic Pictures’ serial productions Adventures of Captain Marvel, Captain America, Spy Smasher, and The Mysterious Dr. Satan courtesy of L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

2 CLIFFHANGER! Cinematic Superheroes of

the Serials: 1941–1952

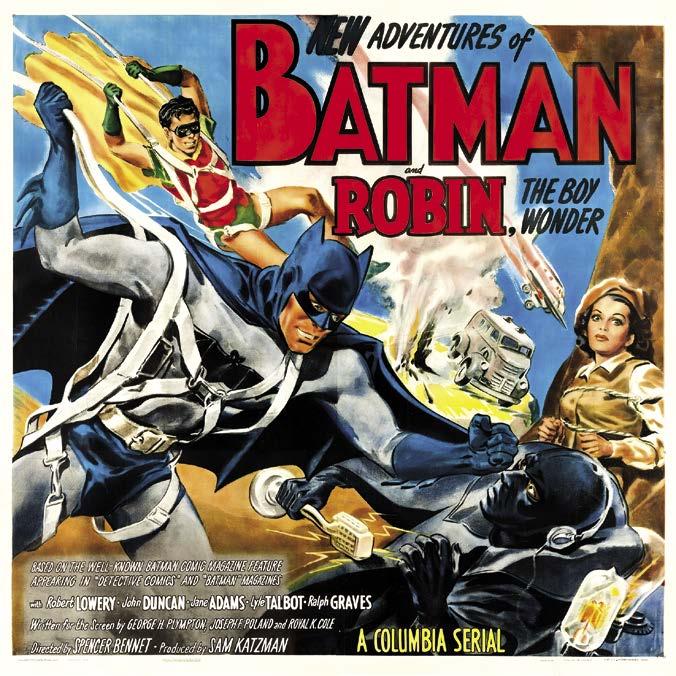

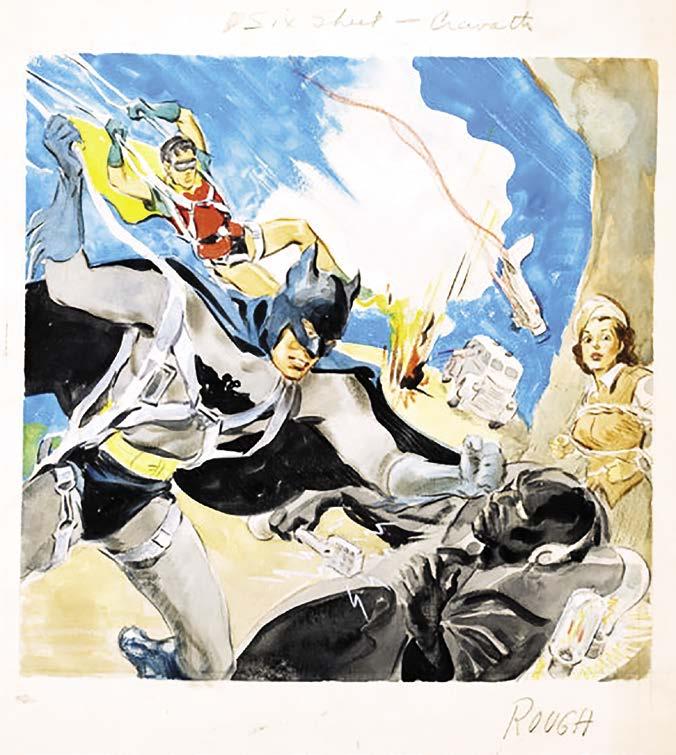

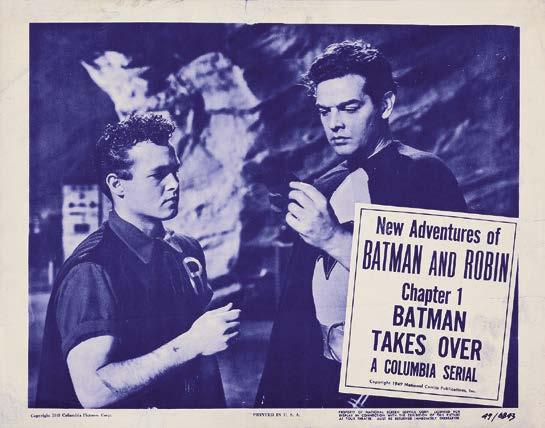

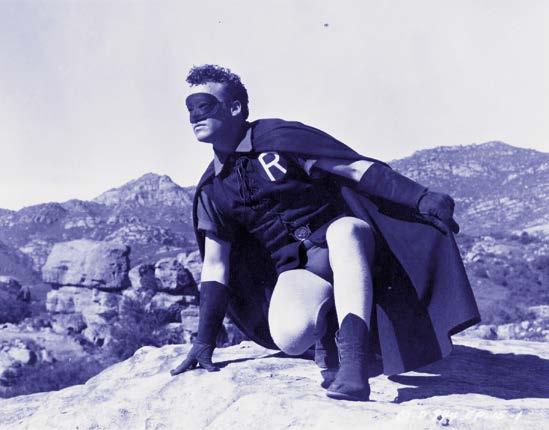

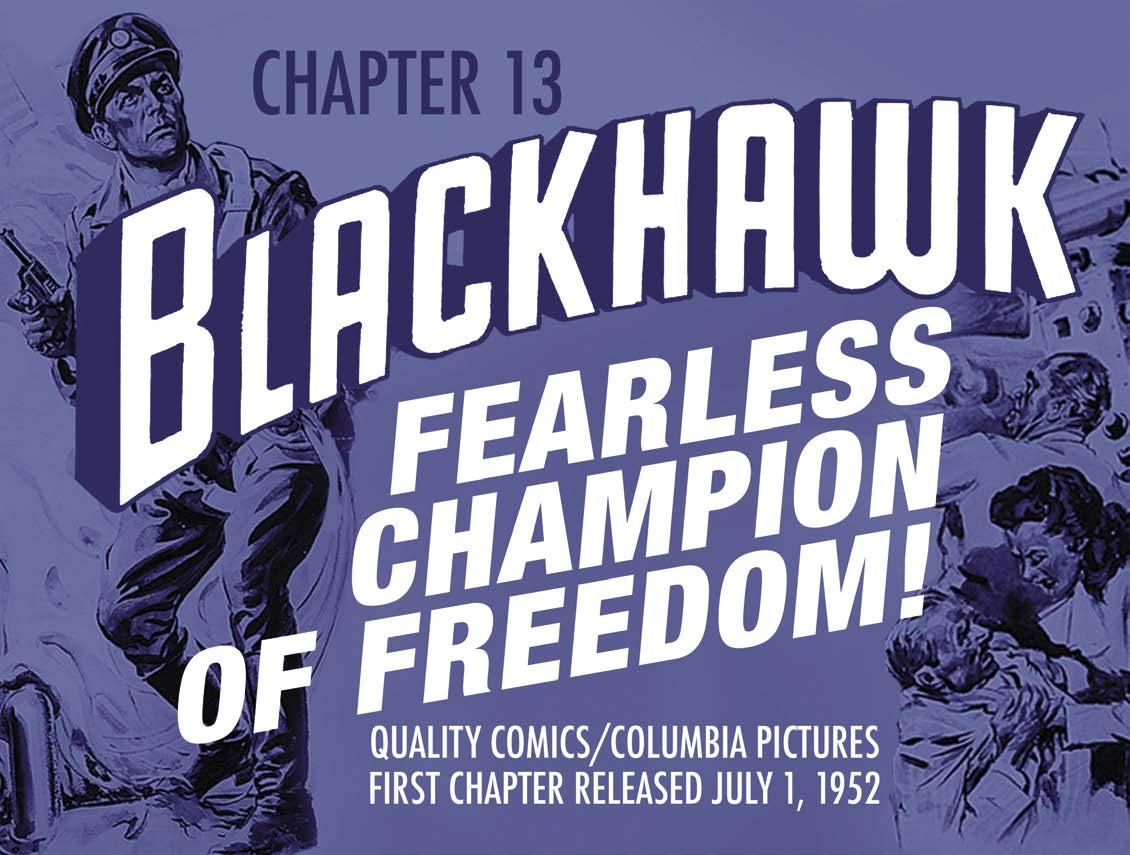

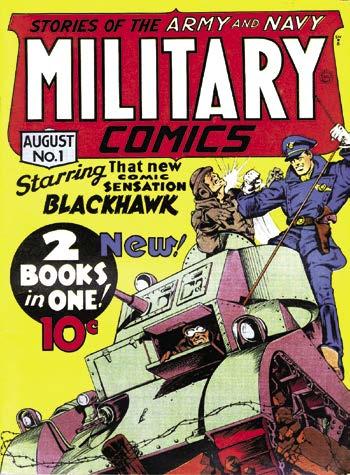

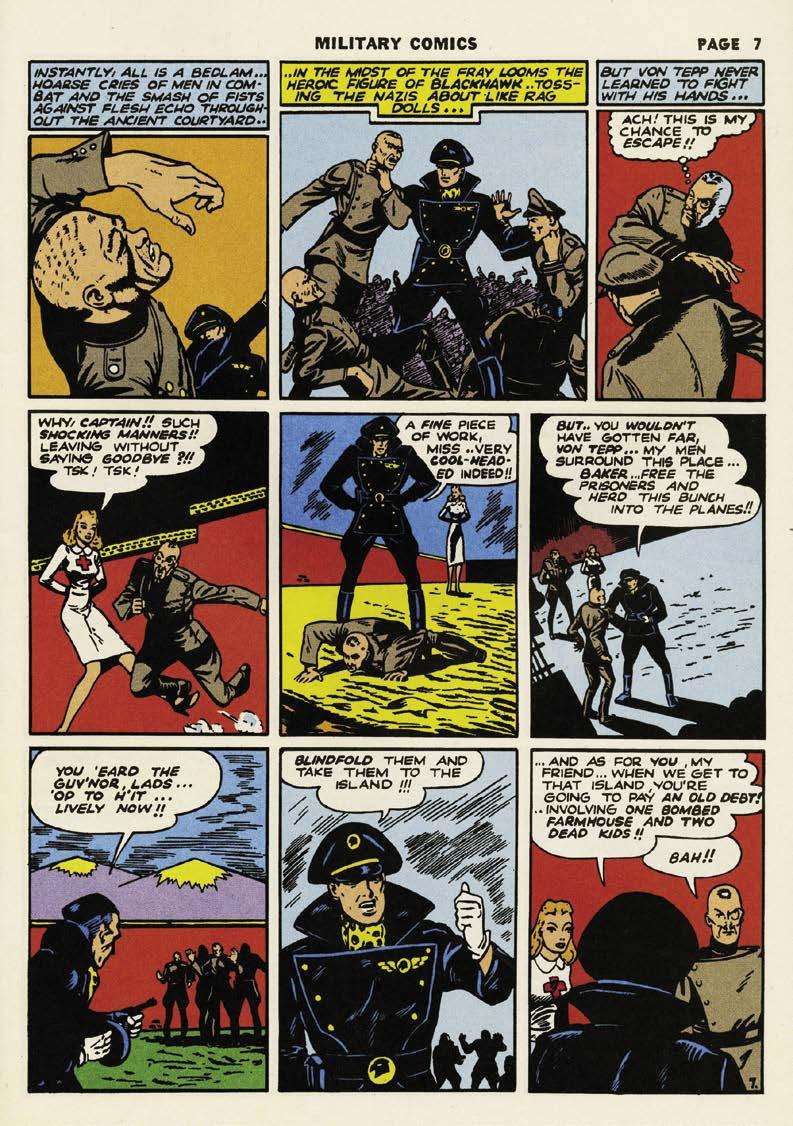

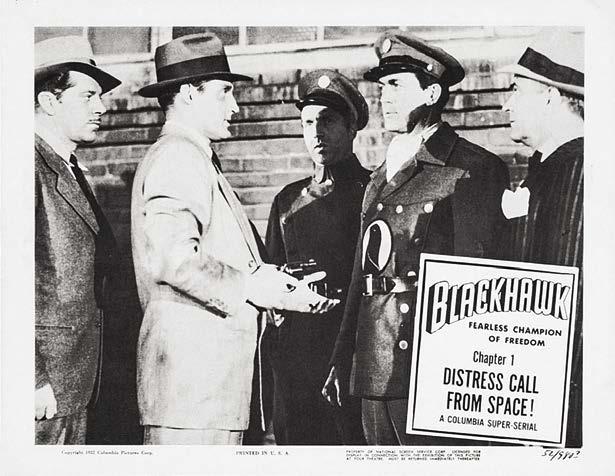

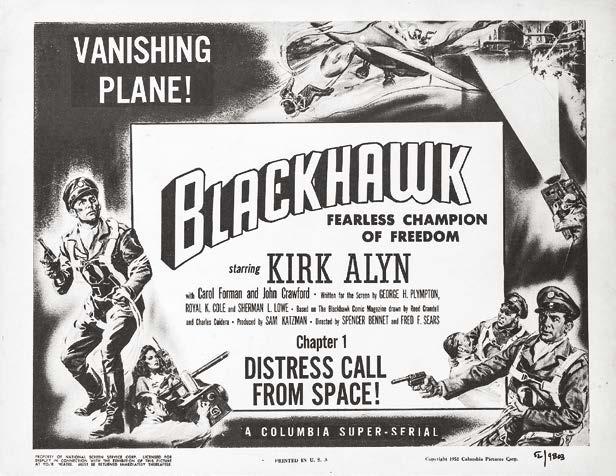

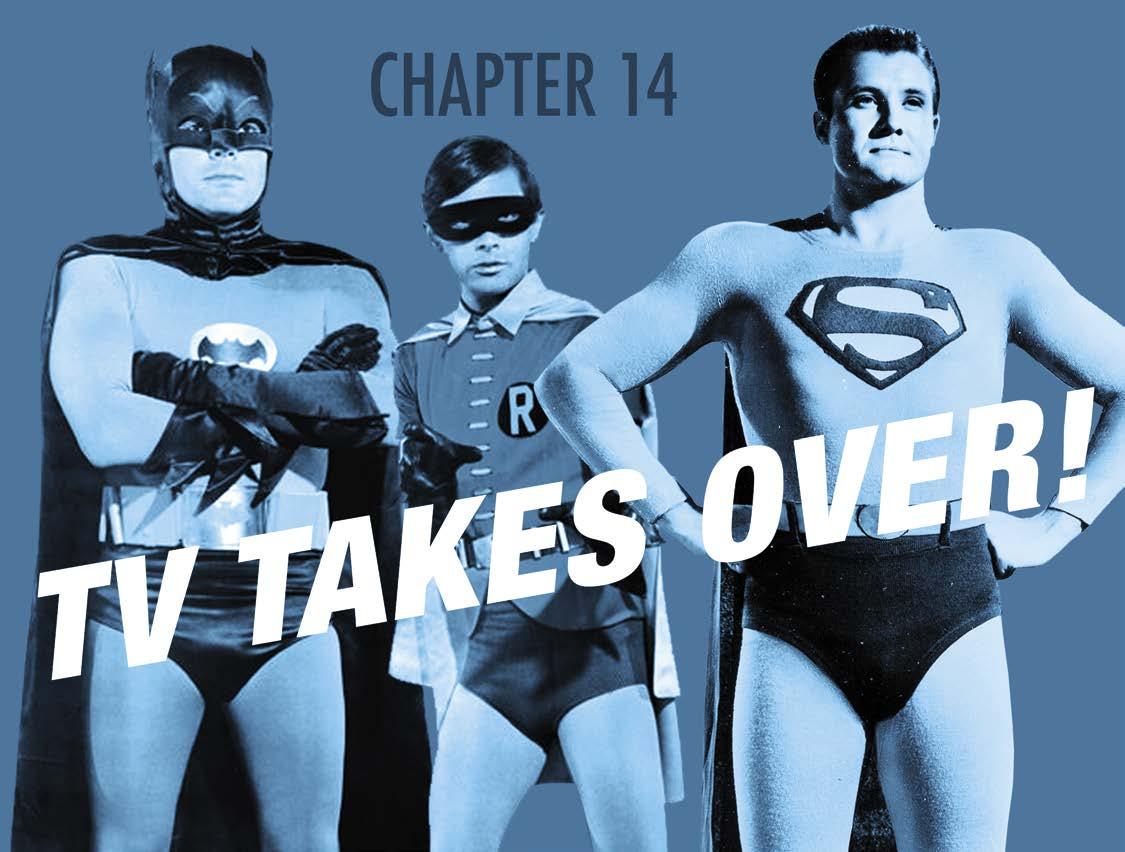

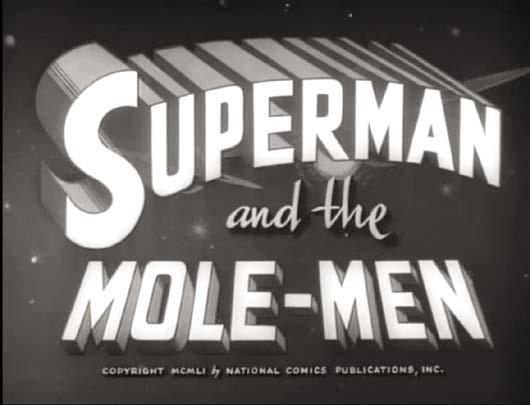

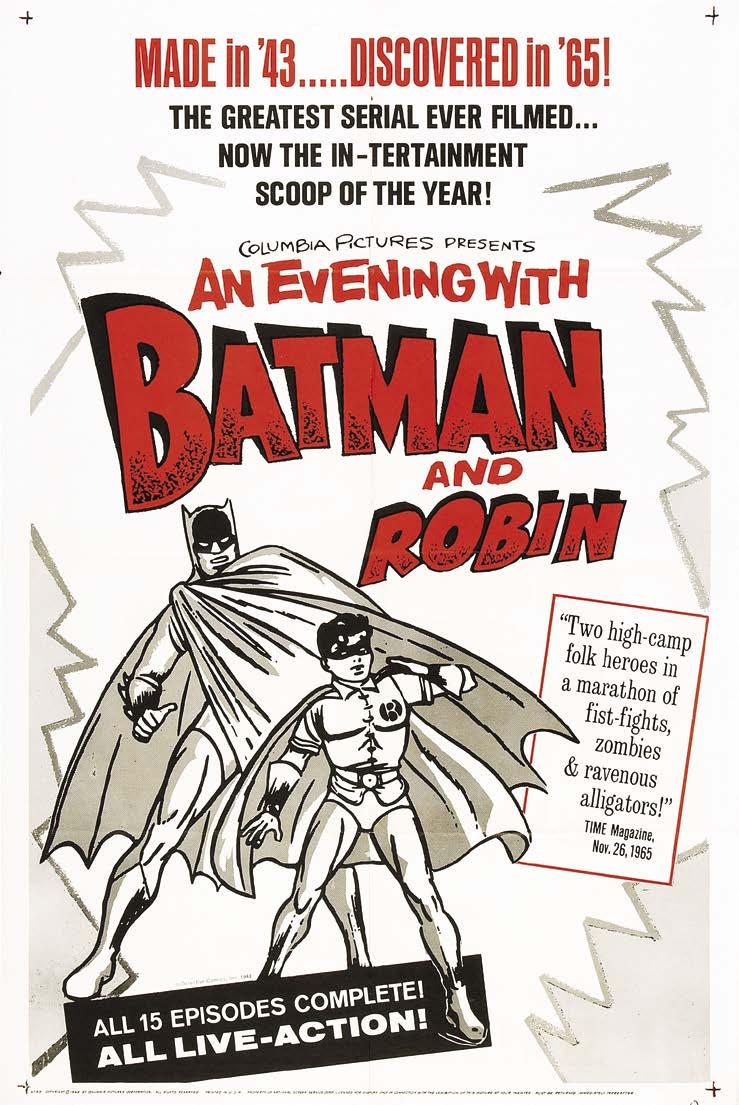

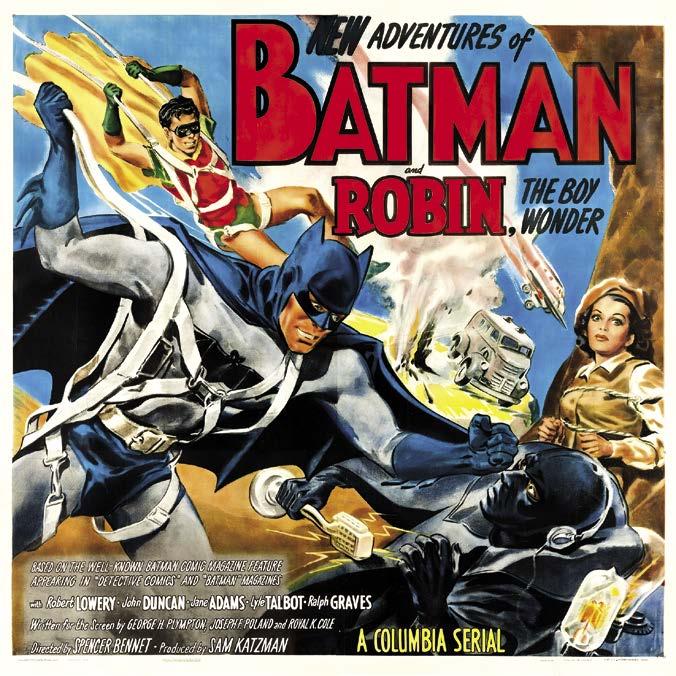

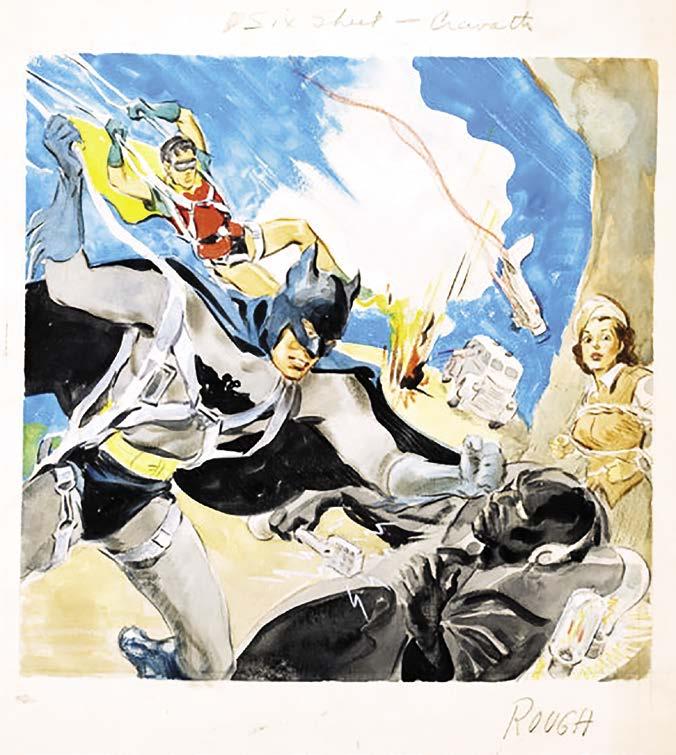

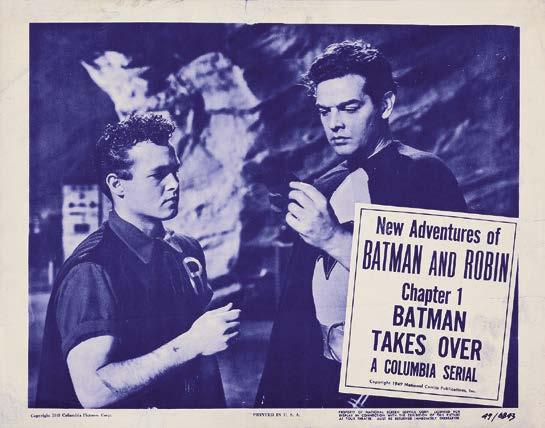

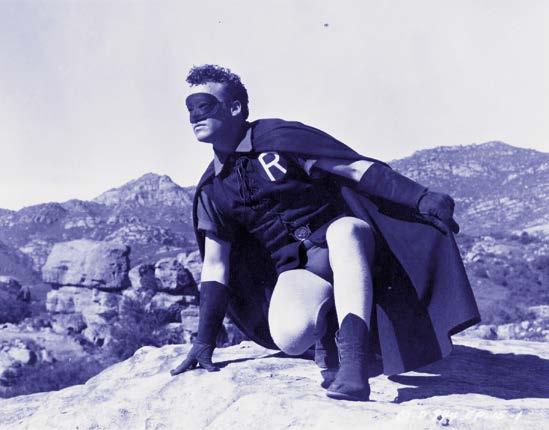

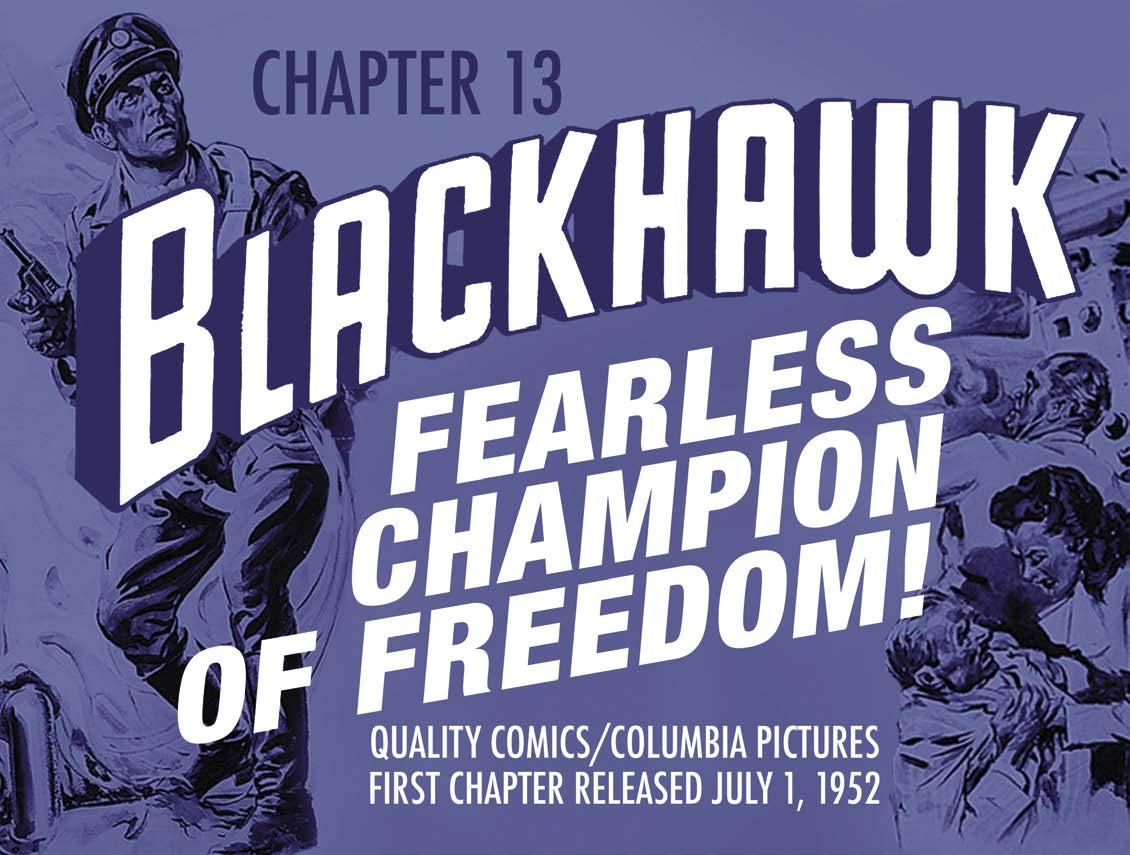

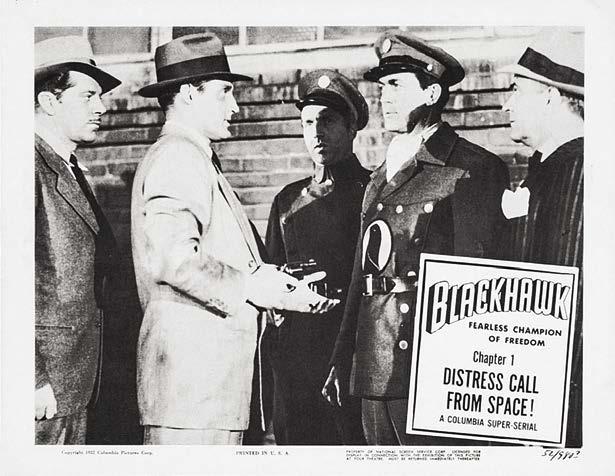

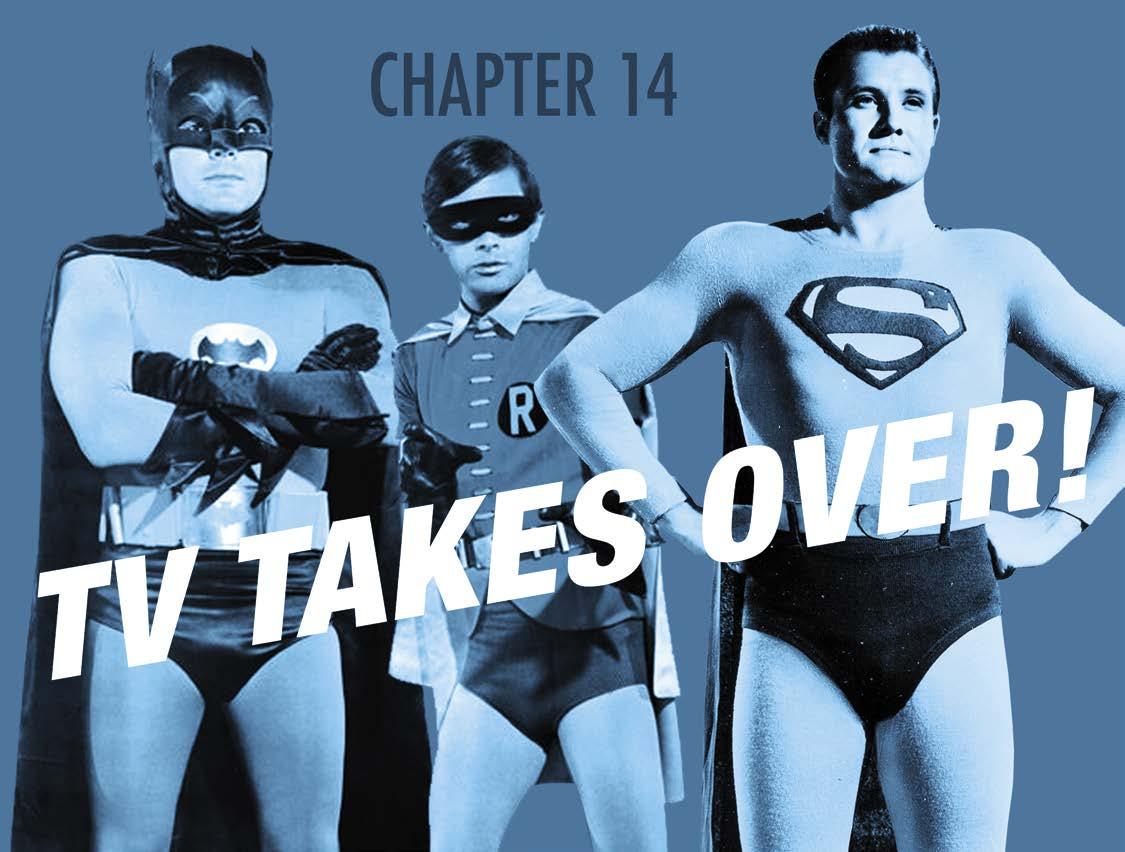

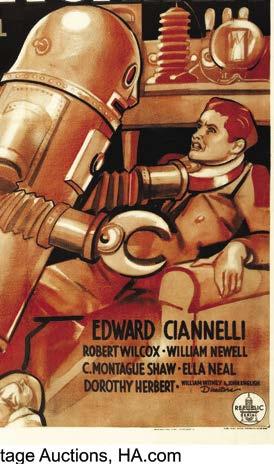

3 Introduction by Christopher Irving ....................... 4 CHAPTER 1: When Mediums Converge! 6 CHAPTER 2: The Adventures of Captain Marvel 32 CHAPTER 3: Fleischer Superman Theatrical Cartoons .......... 48 CHAPTER 4: Spy Smasher ............................. 54 CHAPTER 5: Batman ................................ 64 CHAPTER 6: Captain America .......................... 80 CHAPTER 7: Hop Harrigan ............................ 92 CHAPTER 8: Vigilante ............................... 98 CHAPTER 9: Superman 104 CHAPTER 10: Congo Bill .............................. 116 CHAPTER 11: Batman and Robin ....................... 120 CHAPTER 12: King of the Congo ....................... 128 CHAPTER 13: Blackhawk ............................ 134 CHAPTER 14: TV Takes Over .......................... 144 Select Bibliography ............................... 158 Table of Contents

By the 1930s, America’s cultural landscape–tempered and radically changed by the Great Depression–was redefined by its emerging popular culture and media. The newspaper comic strip, designed to tell a continuing story from day to day, was accessible to even the cash-strapped, and created a shared public experience. Radio was in its Golden Age, with the airwaves dominated by every variety of genre, from kiddie fare to crime thrillers.

Then, there was the movie serial. Once a medium that engaged adult audiences and both created and promoted in tandem with newspaper publishers, these shorts told a serialized singular story. Each chapter ended with a protagonist’s apparent or imminent demise—known as a cliffhanger—and engaged viewers to come back the next week to their local theater. The shorts eventually lost adult audiences to feature length films but, for a short while, silent movie serials were king.

Or, in the case of many of its lead heroines, queens.

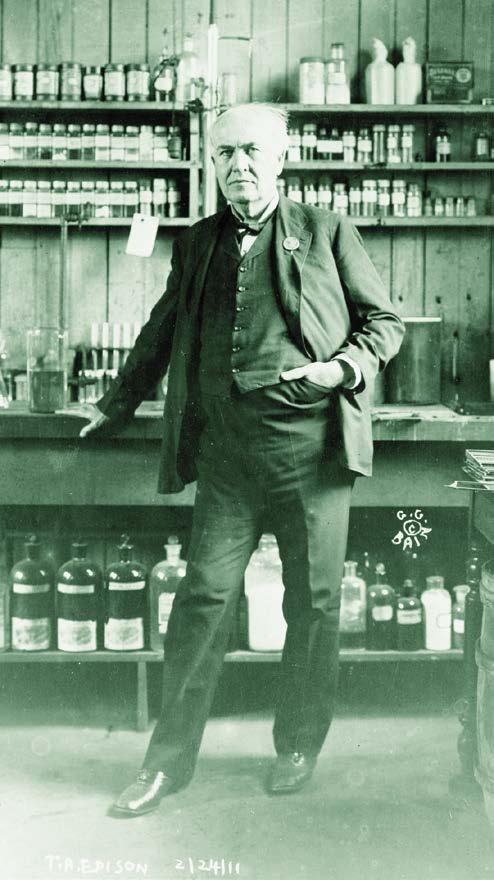

Thomas Edison debuted a 12-reel serial What Happened to Mary in 1912, with the stories appearing concurrently in Ladies’ World magazine. The serial’s first major commercial success came with 1913’s The Adventures of Kathlyn . The first chapter debuted on December 29, 1913 and ran until July the next year.

The Adventures of Kathlyn followed a loyal daughter trying to save her retired Kentucky colonel father from an unscrupulous native chief. The whole point of the “cliffhanger” was to create a hook to get the audiences to come back the next week to see how the protagonist would escape certain death…oftentimes by literally hanging off of a cliff. When Colonel William N. Selig of the Selig Polyscope Company announced his plans to produce Kathlyn , William Randolph Hearst’s newspaper empire approached him about sponsoring the series and cross-promoting it through their Chicago newspapers. The Chicago Tribune swooped in and grabbed the contract from under Hearst and created a short-lived model for serial production: that of newspaper sponsorship that benefited from cross-promotion far stronger than word of mouth or a small ad. Kathlyn’s prose

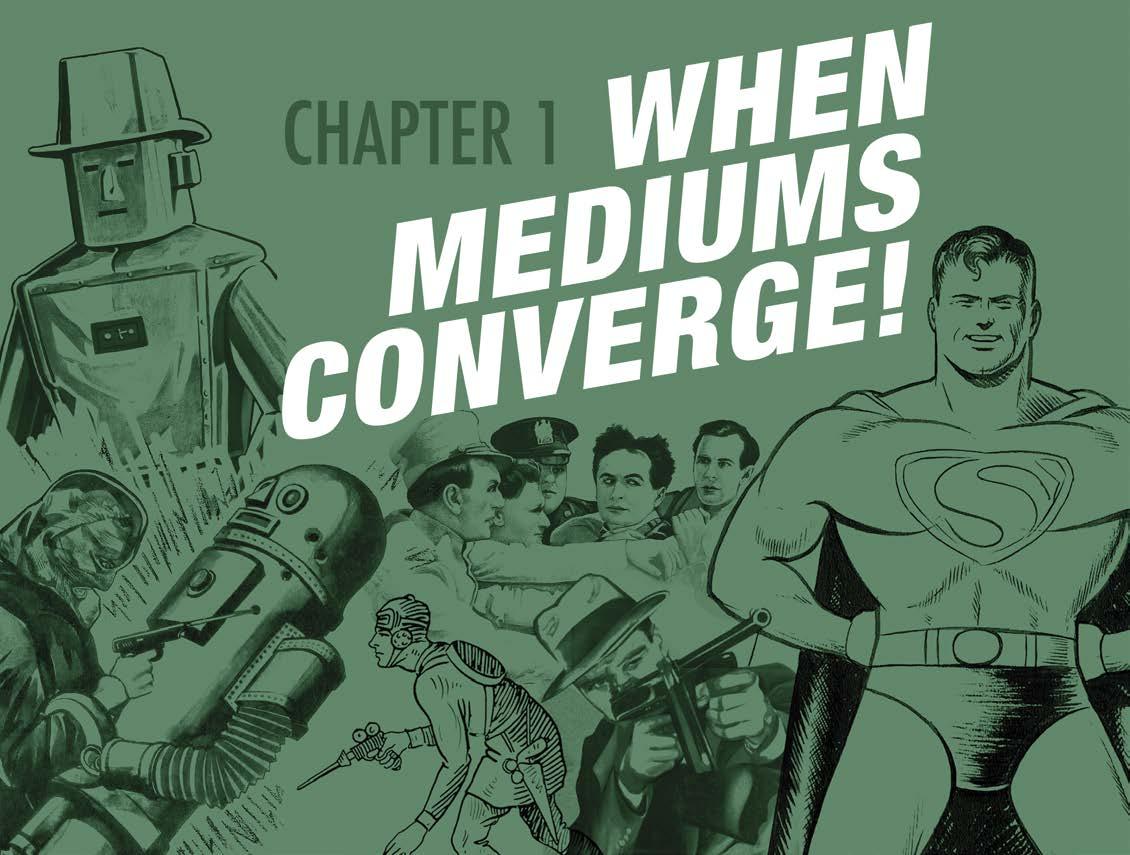

CHAPTER 1:

Mediums Converge! 7

When

counterpart chapters garnered the Tribune approximately 50,000 new readers.

The Perils of Pauline became the first widely successful serial in 1914, thanks in part to the star’s death-defying stuntwork—and the sponsorship and backing of the Hearst papers. This silent film serial starred the first Serial Queen, actress Pearl White, and tagged along with the young heiress through twenty chapters of unprecedented big screen thrills.

The formula established itself quickly enough: the infamous cliffhanger became the end of a chapter, with the subsequent chapter picking up where the last left off, explaining the hero’s sudden escape from death (apparent or anticipated). Sometimes it turned out the hero was not really caught in that explosion (courtesy of a neverrevealed escape not shown in the cliffhanger’s end), or someone would stoop in at the last second in a very deus ex machina way to save them.

Pearl White

Pearl White started acting with the French-owned Pathé films in 1910, and was the daughter of a Missouri farmer. She took to acting to support her family, and found herself making an astronomical $3,000 a week upon Pauline’s success. The profit didn’t just come from her salary (which was $250 a week); Pearl very cannily requested a small percentage of royalties from the films, which ultimately wound up making her an astronomical $10,000,000.

While profiting greatly from her serial work, White apparently frowned upon the movie serial itself. She was so put off by the format that she used to sneak into the Biograph film studio on 14th Street where it was filmed in New York, hoping to not be seen by passersby.

Due to her athletic performances in Pauline and several other actioners (including The Exploits of Elaine, immediately after Perils), age eventually required the use of a stand-in for the more

CLIFFHANGER! Cinematic Superheroes of the Serials: 1941–1952

8

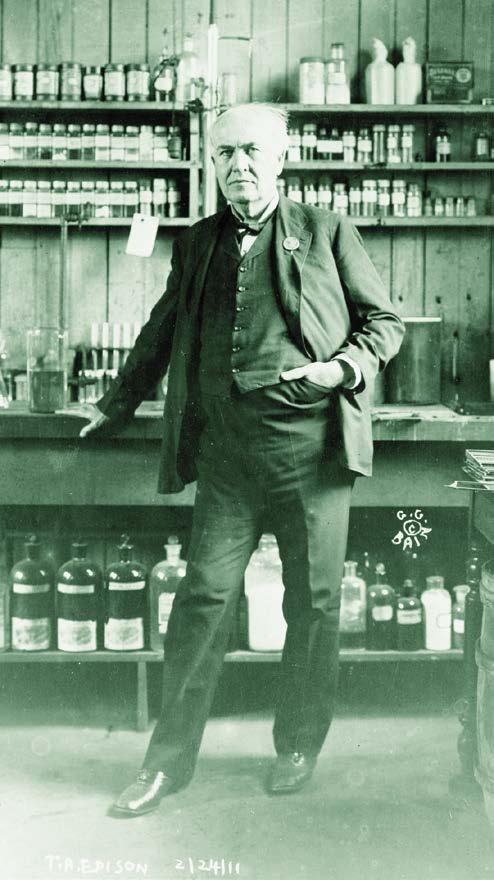

(left) Thomas Edison was also a pioneering innovator and producer of early film, with the goal of owning the film industry. (right) An illustrated poster for another installment of The Perils of Pauline.

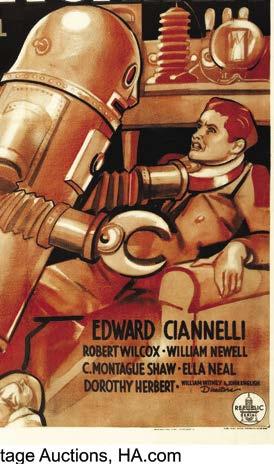

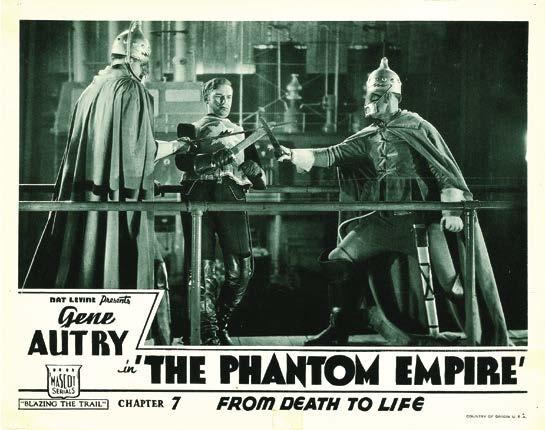

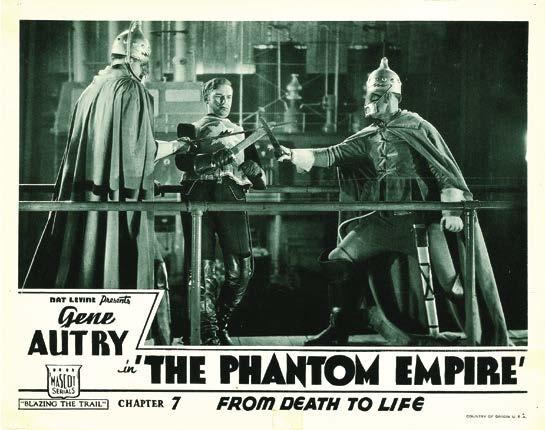

underground empire of Murania with its horse-riding army of Thunder Riders. In the first chapter alone, both Beetson and Queen Tika of Murania come to the mutual conclusion that they need to keep Gene Autry away from doing his successful 2:00 radio program, so that he’ll lose the contract and the ranch will be forced to shut down. Phantom Empire unapologetically mashes sci-fi and Western elements together to create an absurd and surprisingly addictive viewing experience.

The underground world of The Phantom Empire stands on par as a smaller version of the silent masterpiece Metropolis, Fritz Lang’s 1927 German Expressionist science fiction tour-de-force. Flash Gordon ’s influence is deathly apparent in the sci-fi settings of Murania; soldiers wear Roman-styled armor and helmets like the soldiers of Mongo, while even Queen Tika takes a fashion note from Ming the Merciless, wearing lacy versions of his tweaked-out robes. What Tika (played by Dorothy Christy) lacks, however, is the charisma of Raymond’s comic strip world.

Back in a Flash

Flash Gordon wouldn’t wait long. Ignited by the success of their first comic strip adaptation, Tailspin Tommy, Universal procured the rights to produce a serial based upon Flash Gordon for $10,000 and then spent an exorbitant $350,000 on the serial’s budget. Head of serials Henry MacRae got it as part of an optioning blitz of King Features strips, Serials were generally budgeted at $18,000 to $37,000 for all chapters, while Flash’s budget was more on par with a feature’s average $375,000 budget.

At that point, Universal had not only produced the seminal war film All Quiet on the Western Front, but also (through general manager, Carl Laemmle, Jr) launched their iconic line of horror movies, including Dracula with Bela Lugosi, and The Mummy and Frankenstein with Boris Karloff. The monster films came in handy for saving on Flash Gordon’s relatively large budget: many of the sets had been earlier used in The Mummy and The Bride of Frankenstein, while the musical score was also lifted from the horror films.

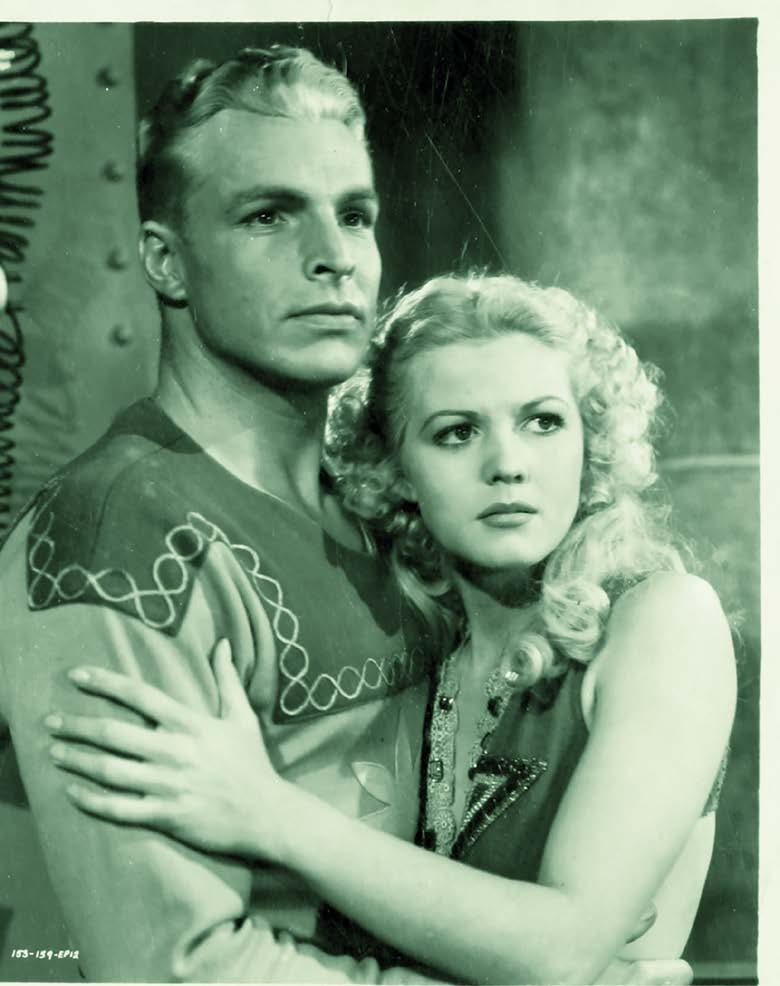

Flash himself was personified in Olympic swimmer-turned-actor Larry “Buster” Crabbe. Growing up in Hawaii, Crabbe was a high school athlete who mostly excelled in swimming. Crabbe placed fourth in the 1928 New Amsterdam Olympics, and then won the gold medal in the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics for the 400-meter freestyle, breaking the record set by Tarzan actor Johnny Weissmuller. Before that, Crabbe set 16 world and American swimming records, winning 35 national championships in the process. Crabbe was not only Weissmuller’s successor in swimming, but in playing Tarzan, when

When

15

CHAPTER 1:

Mediums Converge!

“Gene Autry must die!” according to the baddies in The Phantom Empire

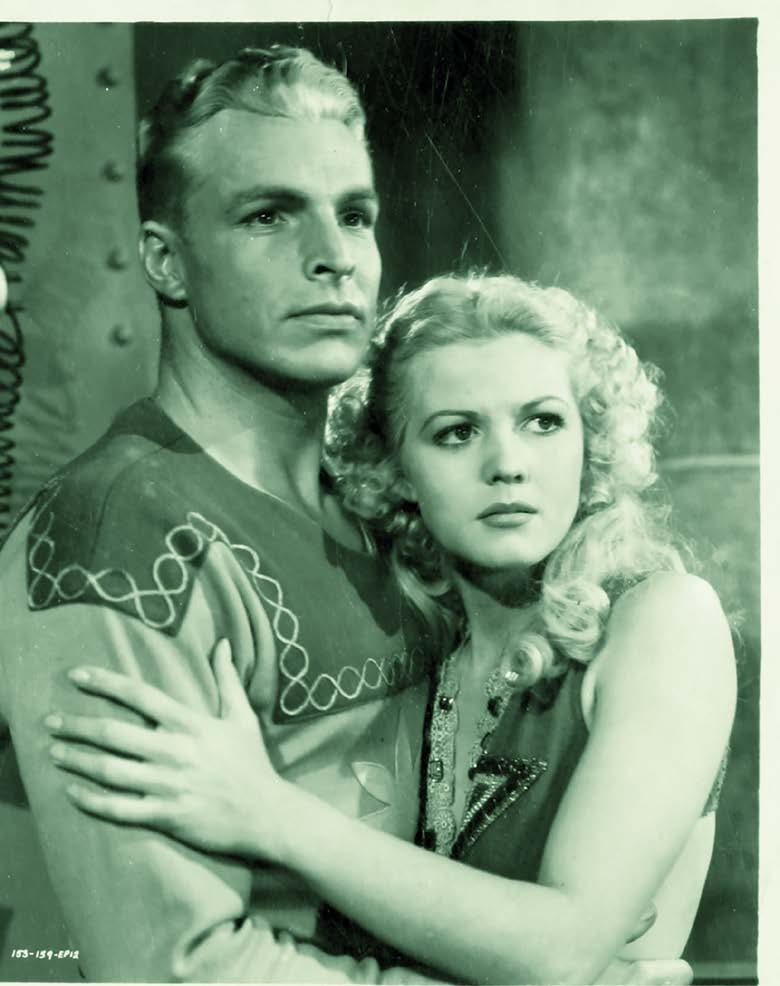

Buster Crabbe and Jean Rogers as Flash and Dale from the blockbuster Flash Gordon serial.

he was cast in 1933’s serial Tarzan the Fearless for Principal Pictures. From there on, Crabbe was a Paramount man, starring in ten Westerns based on the work of author Zane Grey from 1933 to 1937. Universal very wisely borrowed Crabbe for the Flash Gordon serial and the role elevated him to becoming the first King of the Movie Serials. He played Flash with a sincerity and authority that, despite his lack of fine acting skills, furthered the serial’s own verisimilitude.

“An actor of the serious tradition might have betrayed his lack of belief in the part,” Raymond Stedman wrote in The Serials, “but nothing in Crabbe’s manner or voice could be interpreted as a message to the audience that the whole thing was nonsense.”

Charles Middleton’s Ming the Merciless set a precedent for the science fiction villain. He oozed sinister as the cold-blooded villain who never managed to off Flash and his friends, as his flair for dramatic death traps ironically wound up hampering his chances for success. Middleton was born on October 7, 1879 in Elizabethtown, Kentucky, just a bit more than a decade past the end of the Civil War. His father raised thoroughbreds and, since Charles grew up handling them, he eventually became a professional rodeo rider. While riding at the St. Louis Exposition, he met his wife Leora Spillmeyer.

Charles’ stage acting led into his first film role in 1920’s silent The $1,000,000,000 Reward . He continued to work in both stage and film, landing his first talkie role in The Bellamy Trial in 1928. Movie serials snagged him in the type of roles he’d become best known for: the villainous mastermind, as seen in legendary screen cowboy Tom Mix’s final serial, The Miracle Rider in 1935.

Rounding out the cast of Flash was the stunning Jean Rogers as a blonde Dale Arden (they dyed her hair brown in the sequel to more closely resemble her comic strip counterpart), and Frank Shannon as the fatherly and wise Dr. Hans Zarkov.

Flash Gordon opens with natural disasters that take Flash, Dale, and Zarkov in the scientist’s rocket to the planet Mongo to keep it from colliding with the Earth, which feels the destructive effects of the hurtling planet through the use of stock footage. After their ship lands, they barely escape from being eaten by giant lizards, and find themselves captives of Ming the Merciless, ruler of Mongo. The model ships were awkward and jerky in their flight (courtesy of the strings they hung from) and the oversized lizards were tiny reptiles filmed in close-up. The lasers were scratched into the film, and the costumes were garish and skimpy by pre-Code standards, but it nailed the aesthetic of Raymond’s designs. Crabbe’s powerful physique, and the scantily clad costumes worn by the women, replicated the romance of the strip—even if the serials were completely absurd.

The Flash Gordon strip pushed comic strips into new worlds that were unprecedented on the Sunday comics page and was an enormous commercial success for Universal, apparently earning the studio more money in 1937 than any production save one (Three Smart Girls, starring Deanna Durbin). Most importantly, Flash further cemented the fantastic comic strip world as possible and profitable fodder for kiddie audiences.

CLIFFHANGER! Cinematic Superheroes of the Serials: 1941–1952

16

The Universal Pictures title card from 1927-1936.

Charles Middleton oozed evil as Ming the Merciless.

Gene Autry’s cross-country touring got him in front of more fans than the average Hollywood A-lister, and helped him build a dedicated fan base. It was the same for Roy Rogers, Smiley Burnette (Gene’s funnyman sidekick who made 1,000 appearances in a six-year period), and Don Barry.

To make it financially worth their stars’ while, Republic didn’t take a percentage of the money made at the appearances, encouraging their stars to do their PR for them.

Another clever move on Republic’s part was with their producer and scout Armand Schaefer, who sought out regional acts to appear in their serials and films. Basically, Republic would fly these acts onto their studio lot for a weekend, shoot their cameo and pay them about $1,000 to $1,500 for their time. They sent them back to their native region, relying upon the act’s own penchant for self-promotion to get the word out about whatever film they’d appeared in.

Republic’s budget for all sixty pictures produced in 1940 was only $9,000,000, or an average of $150,000 a picture.

Enter The Scourge Of The Newsstands: The Comic Book!

“Actually, the comics started with the whole Superman/ Batman thing in the middle of the Depression. If you were a married homeowner, you’d be making $20 to $30 a week and living a good life. We were getting $5 a page and all we had to do was invent the character, write the script, letter it, erase it, and wait ninety days for $45. There were surprises, and everybody was taken advantage of. But, hey, we were working, making $75 a week, $85, $90.

“The only problem was, all the guys I knew (including myself and especially Jack Kirby) wanted to be steadily employed. I guess we were a product of our times and the whole Depression. We had to make our work, and manufacture and imagine it.”

—Joe Simon

CHAPTER 1: When Mediums Converge! 23

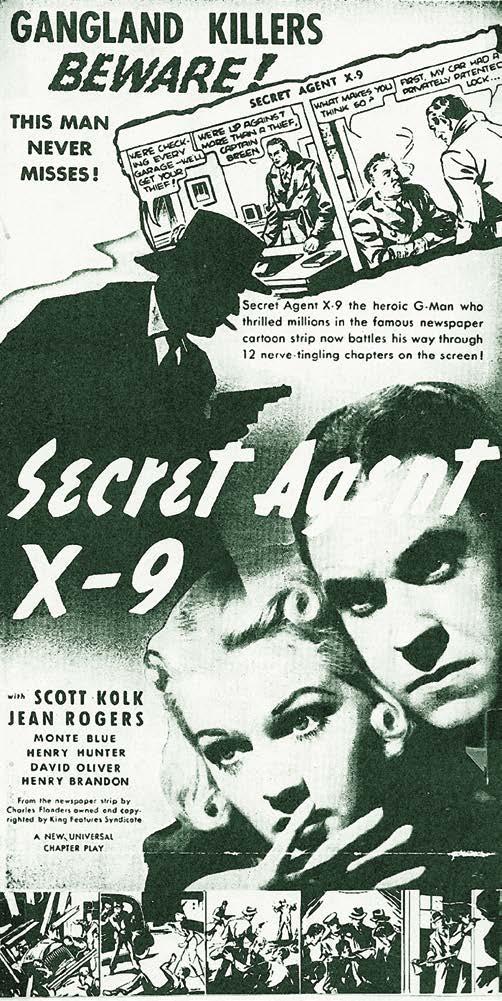

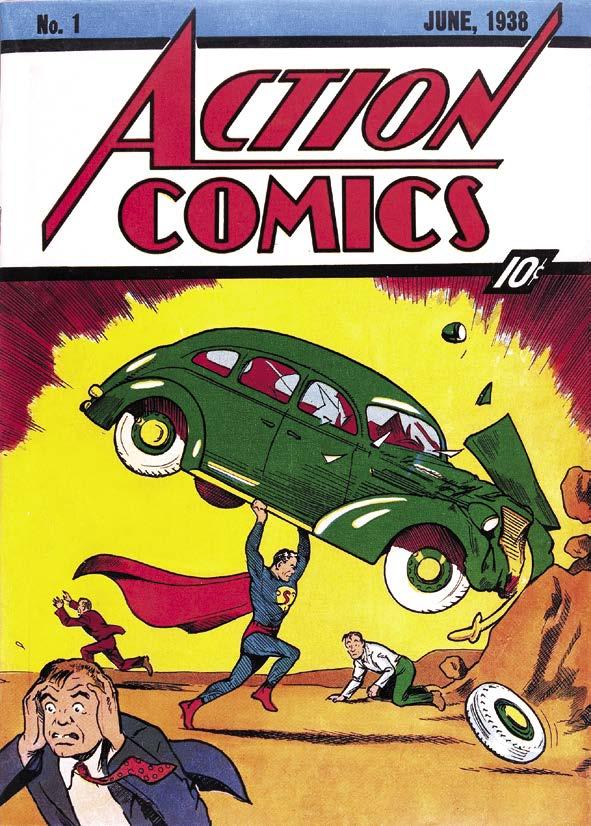

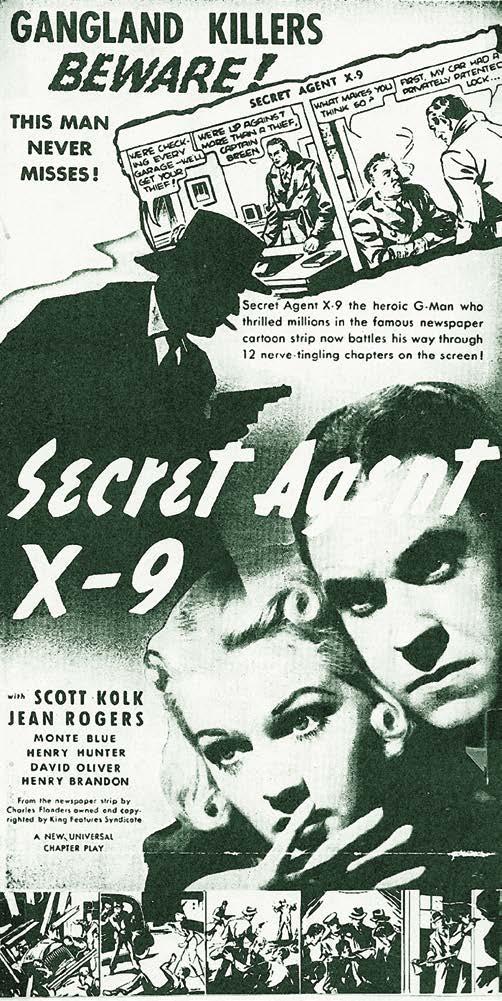

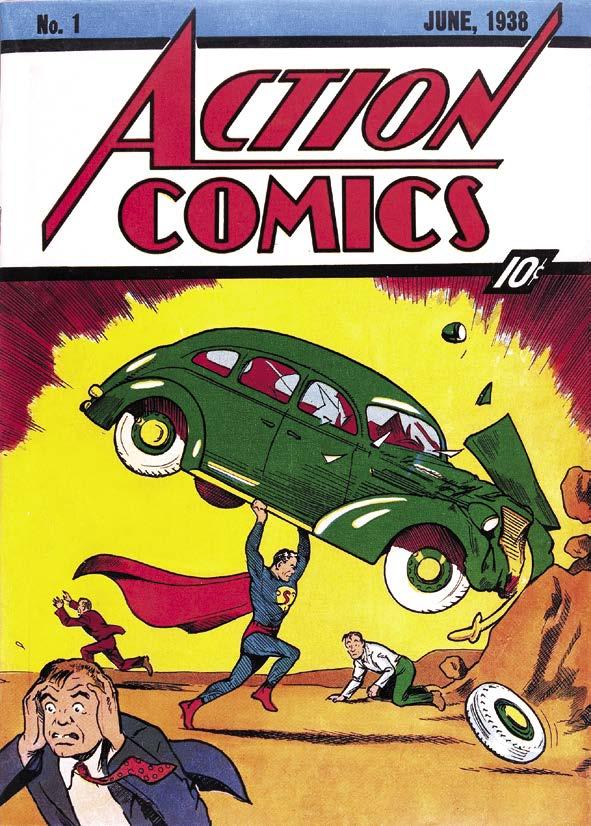

(left) The comic strip connection to the Secret Agent X-9 serial is no mystery in this ad. (right) The spit-curled face that launched a genre: Superman makes his debut in Action Comics #1, 1938.

The comic book, a pamphlet that reprinted newspaper comic strips in the 1920s, started printing original comic strip material towards the mid-‘30s. Any success that the comic strip-derived medium had enjoyed prior to June, 1938 would soon be overshadowed by the blue-and-red clad cultural behemoth that stood on the cover of Action Comics #1. Holding a large automobile over his athletic wrestler’s body, wearing a dark blue bodysuit with a dramatic red cape billowing out and off of his powerful shoulders, Superman took the newsstands by storm and launched the superhero genre.

This powerful figure from another planet emerged from the minds of two bookish teenagers from Cleveland, Ohio. The story of Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s stormy career as Superman’s creators is as iconic as their own creation and full of tragedy, triumph, and disappointment.

Jerry Siegel was born to Lithuanian immigrants Mitchell and Sarah Siegel on October 17, 1914, growing up in the Cleveland suburb of Glenville. That same year, Joe Shuster was born in Toronto, Canada and his family would cross the border to Cleveland, Ohio when he was only nine.

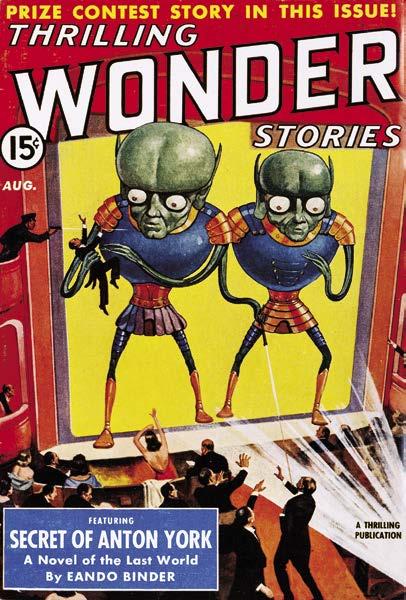

Both boys latched on to the emerging field of “scientifiction” with editor Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories. The August, 1928 issue affected young Jerry Siegel for the rest of his life: the cover featured a red-clad man with a rocket pack strapped to his back from writer Elmer Smith’s (with co-writer Lee Hawkins Garby) serialized story “The Skylark of Space”—also the same issue as Anthony Rogers’ debut in “Armageddon 2419.” The next year, an inspired Jerry created what may have been the first science fiction fanzine: Cosmic Stories, mimeographed and featuring Jerry’s hyperbolic stories and editorials.

In 1932, Jerry’s life was forever changed when his father Mitchell was held up at the haberdashery shop he owned and shot in the chest. After his mother and cousins basically swept the murder under the rug and refused to dwell on it (the unsolved murder was changed to “a heart attack” in some stories), Jerry found himself even further withdrawn, and often holed himself up in the attic while writing his science fiction stories.

Joe Shuster, meanwhile, struggled on the streets of Cleveland as a paperboy to support his family. His father, an unsuccessful

tailor, brought scraps of paper and brown bags home for Joe to draw on the back of as the Shuster family could rarely even afford regular drawing paper. Joe, a scrawny kid, decided to focus on bodybuilding, perhaps to compensate for his social awkwardness; it was a hobby he pursued for about four or five more years.

It was a fateful day in 1930 that the two met in the office of their high school paper, the Glenville Torch , introduced by Jerry’s cousin. They were cut from the same cloth: both shy, awkward, maladjusted 16-year-olds who found their refuge in the escapism of early science fiction.

“When Joe and I met,” Siegel observed in 1983, “it was like the right chemicals coming together.”

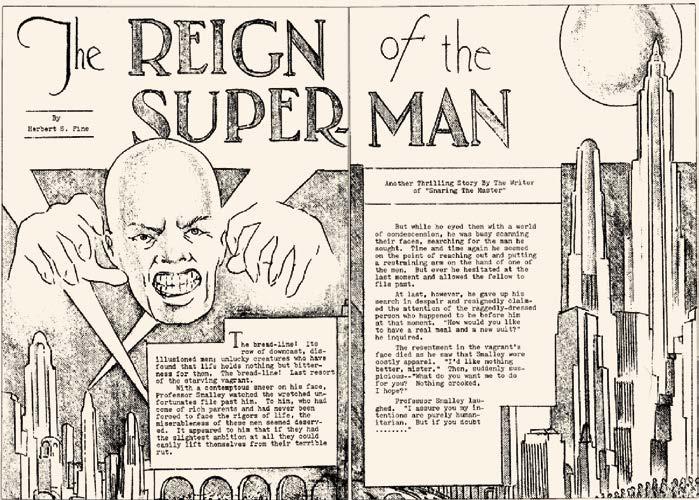

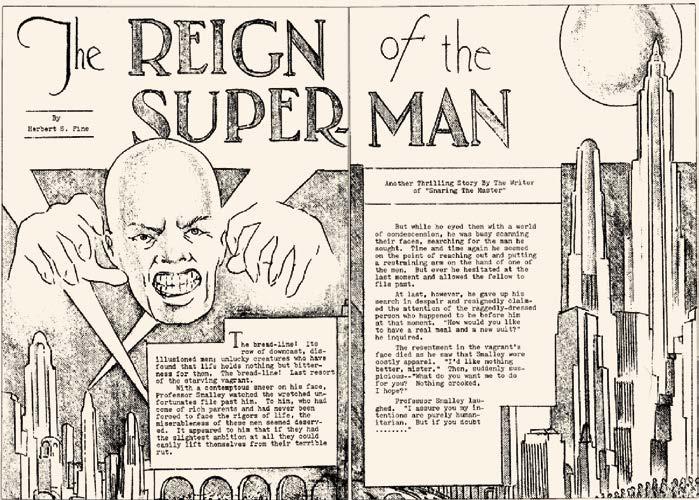

Jerry and Joe began collaborating on everything from comic strips (sent by a hopeful Jerry to Syndicates) to pulp fan magazines. Their most significant early collaboration was their January, 1933 fanzine, Science Fiction: The Advance Guard of Future Civilization , which included the story “The Reign of the Superman.” This prototypical version of their iconic hero had more in common with their villain Ultra Humanite than Superman, however: he was a bald villain with great mental powers gained through scientific means. Joe provided illustrations in which a vagrant is experimented on by a mad scientist and given great mental powers. Facing off against a crusading journalist by a crusading journalist during his bid to rule the world, he returns to vagrancy when he realizes that his powers are only temporary and on the verge of fading away.

Another influence emerged in Jerry’s life in 1932, when he read and reviewed Philip Wylie’s novel Gladiator, a novel about a superman who is the result of his father’s eugenic experiments. Given bulletproof skin and super strength, he struggles through life trying to make a difference to the greater man. Instead, he encounters mankind’s own cruelty, selfishness, and limitations on his journey. Reading Gladiator, the similarities between it and the future Superman are impossible to not notice.

CLIFFHANGER! Cinematic Superheroes of the Serials: 1941–1952

24

Siegel and Shuster’s first Superman, a mentally powered villain, from their 1933 fanzine.

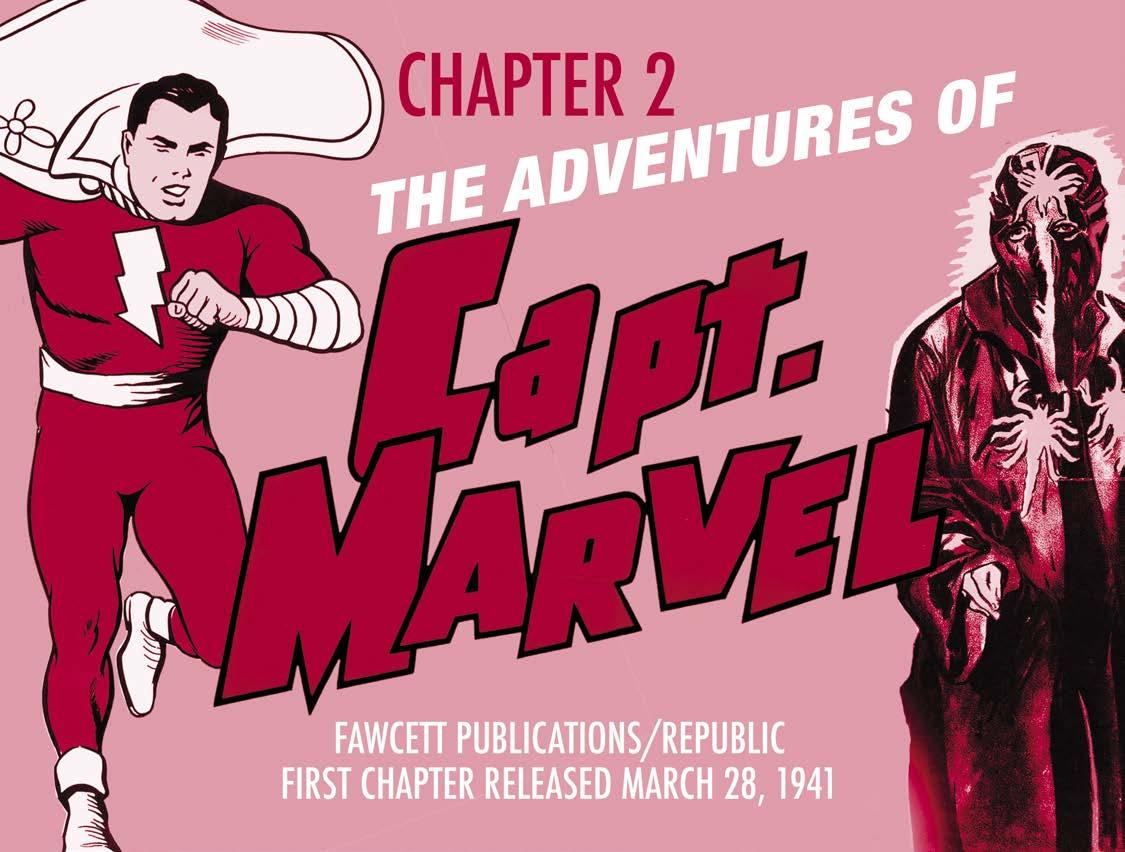

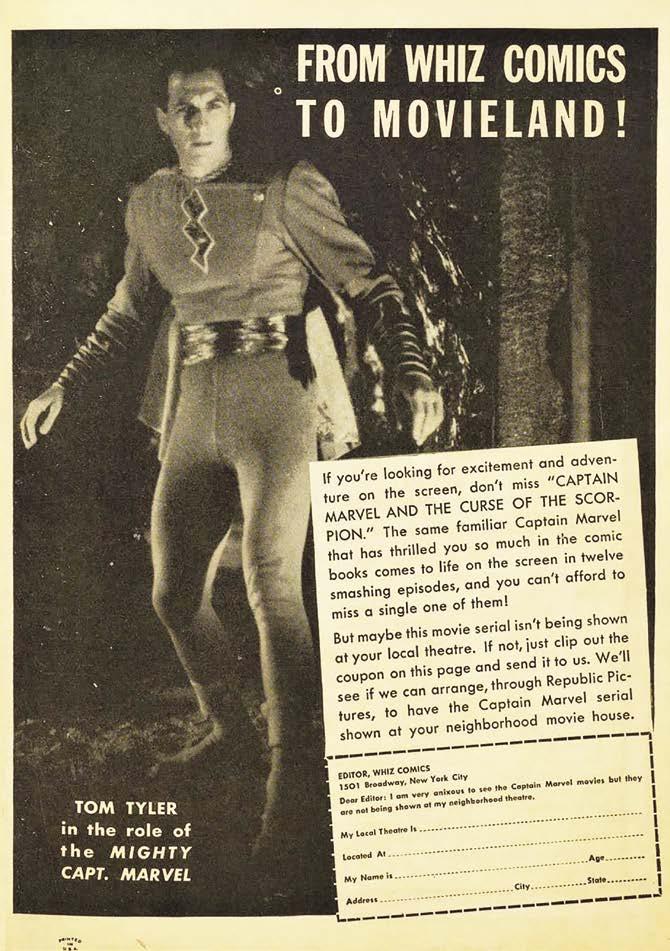

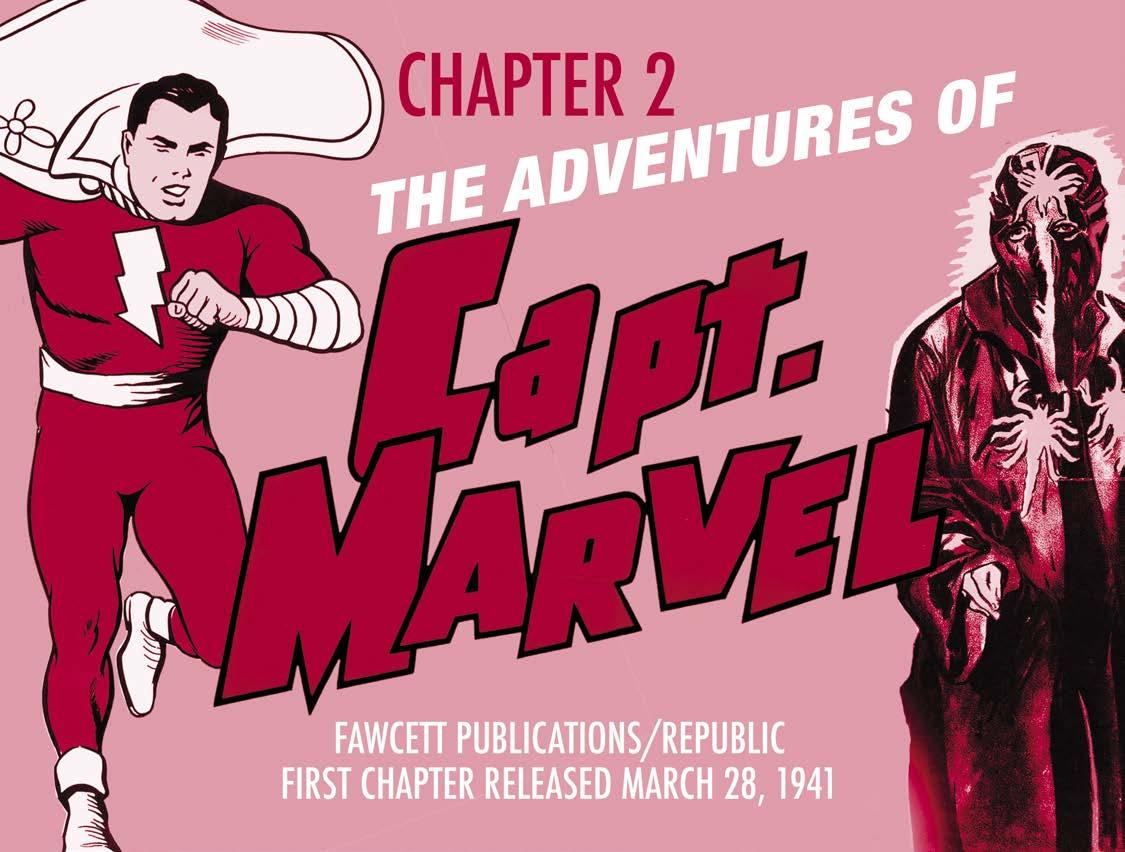

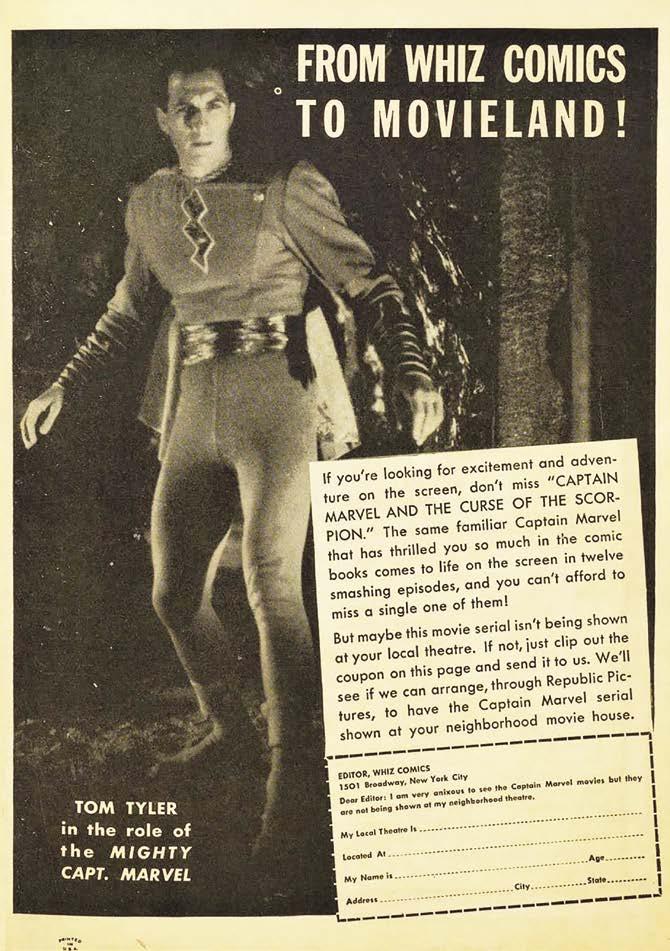

After failing to procure the Man of Steel two years in a row, Republic was still able to become the first to squeeze out the first live-action superhero. Since they couldn’t get Superman, they snatched up his red-suited competitor: Fawcett Publications’ Captain Marvel, when that publisher approached them shortly after the Superman deal fell apart in 1940. The end result is one of the most beloved movie serials of the era, and one of the most complex and long-running legal cases in comic book history.

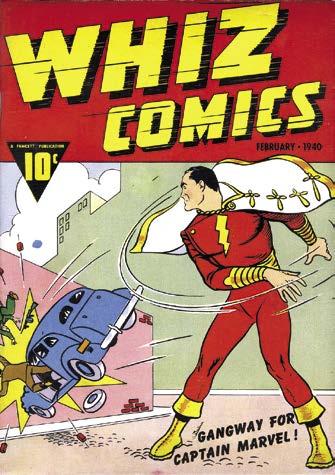

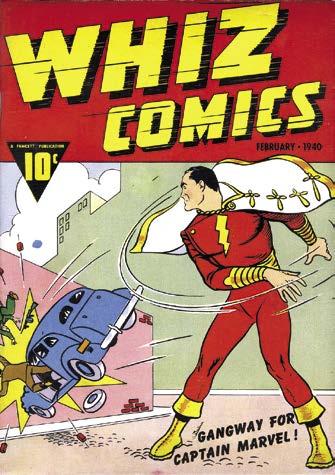

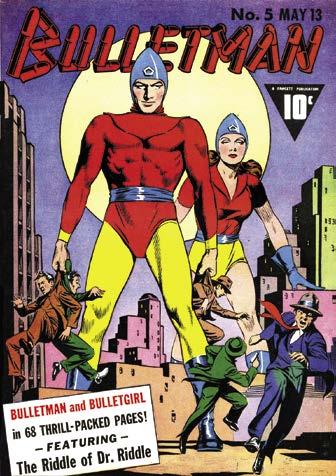

Fawcett began publishing in 1920 with Wilford Fawcett’s digest-sized joke magazine Captain Billy’s Whiz Bang . By the next decade, Fawcett’s other magazines included True Confessions , Smokehouse Magazine , and Mechanix Illustrated . When the comic book debuted in the ‘30s, Fawcett hopped on the bandwagon with Whiz Comics #2 in February 1940. The star of the book was the red-suited Captain Marvel, clad in a militaristic uniform with a red shirt-flap, golden gauntlets, and a short white-and-gold trimmed cape slung over his left shoulder. A powerful lightning bolt was emblazoned on the front of his crimson tunic, and his cape flapped as he tossed a large blue car into a brick wall. It may not have been as iconic as Superman

33

CHAPTER 2: The Adventures of Captain Marvel

The good Captain makes his debut, from the cover of Whiz Comics #2 (Feb. 1940). Art by C.C. Beck.

lifting a car over his head on the cover of Action Comics #1, but it came pretty darn close.

Fawcett decided to start publishing comic books in August, 1939 and appointed William “Bill” Parker editor of what would become Whiz Comics . He tasked Ralph Daigh and Al Allard with getting the line a major superhero.

The creation of Captain Marvel was far more planned than that of Superman’s: Originally envisioned by Fawcett staff writer Bill Parker as a team of superheroes led by Captain Thunder, the decision was then made to whittle the group (reports vary from four to six) down to just Captain Thunder himself. Conceived by Parker, the Captain’s alter ego would be a poor orphan boy to create a firm contrast to the superhero. When Charles Clarence (C.C.) Beck came on as head of cartooning, he devised close to two dozen concept designs. For the Captain’s good looks, Beck turned to the likenesses of movie star Fred MacMurray; Roscoe Fawcett would later liken the good Captain to Cary Grant.

The writer of Captain Marvel ’s adventures, Bill Parker joined Fawcett in 1937 as a magazine editor and was not a fan of the comic book format. The growing costumed hero trend found Parker assigned with editing and writing the first Whiz Comics , where he co-created Captain Marvel, Spy Smasher, Ibis the Invincible, and Golden Arrow with artist C.C. Beck.

Perhaps it was Parker’s detachment from the fantasy and hero genres that gave Captain Marvel that tendency to not take itself too seriously.

Beck called his hometown of Zumbrota, Minnesota as a place Walt Disney would have loved, a small American town with a Main Street, wooden sidewalks, and live music playing in the park. Founded by German and Scandinavian settlers in 1856, Zumbrota’s current claim is that they have Minnesota’s only remaining original covered bridge. On June 8, 1910, Charles Clarence Beck was born to a school teacher mother and a preacher father. Beck was the proverbial “doodler” and avid reader of the Roaring Twenties and Great Depression comics pages, leaning towards more simplistic humor strips than highly-detailed action ones.

Mostly self-taught, Beck went to the Chicago Academy and the University of Minnesota. Shortly after, he got his first art job tracing comic strip characters onto hand-drawn lampshades. By 1933, he was a staff artist at Fawcett Publications, working on many of their humor magazines (including the infamous Whiz-Bang ).

“I had nothing to do with either the characters or their actions,” Beck claimed, denying any claim to character creation. “I simply put them into picture form…They were conceived in Parker’s mind; I was just the doctor who held them up and slapped them on their bottoms to make them draw their first breaths.”

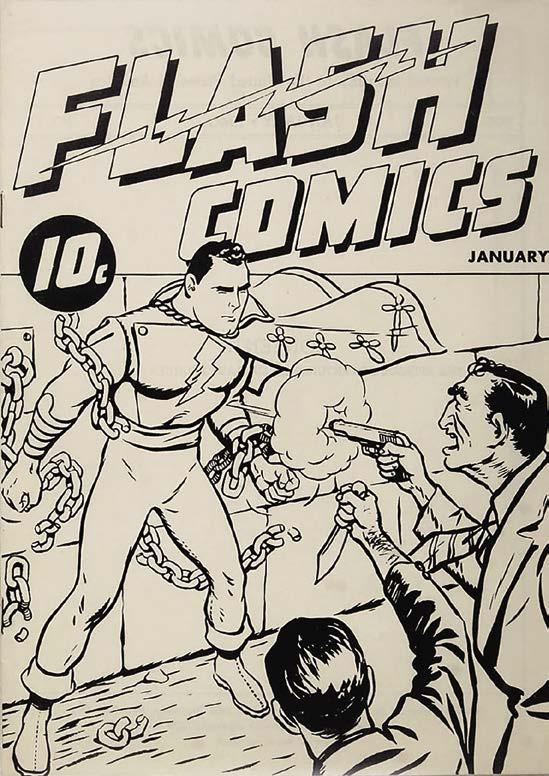

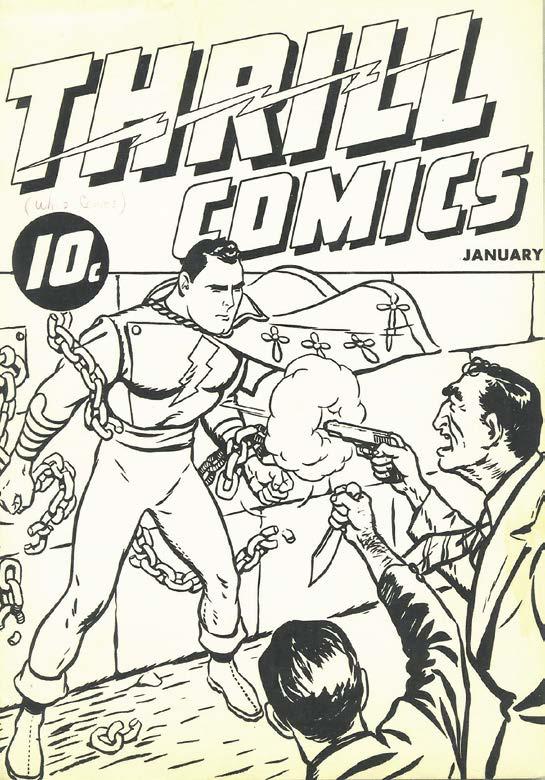

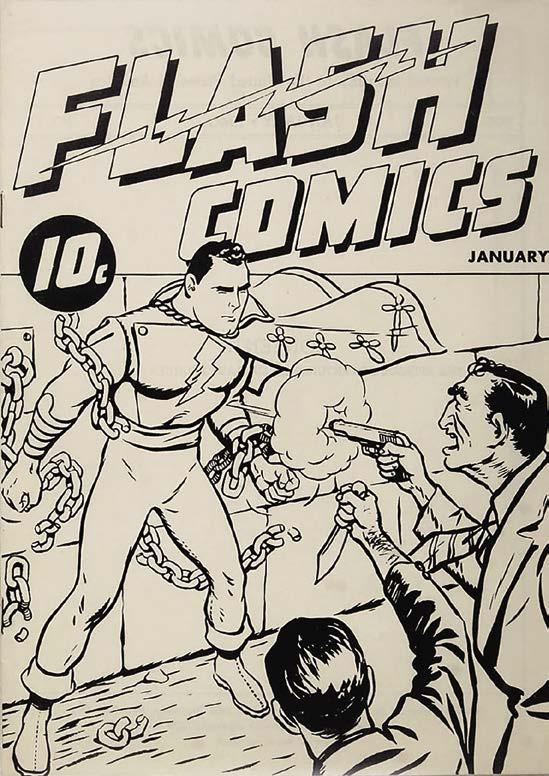

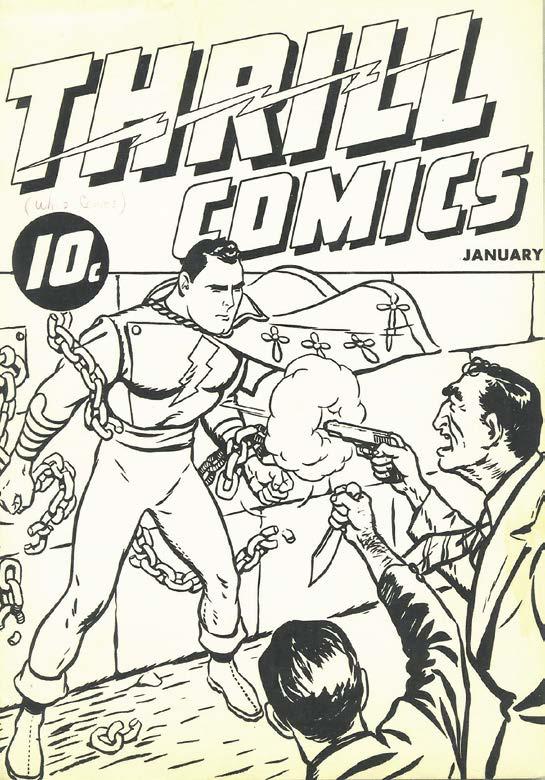

The first story was drawn with the Captain Thunder name, and printed in disposable black and white in-house

34

CLIFFHANGER! Cinematic Superheroes of the Serials: 1941–1952

Ashcans for Fawcett’s 1940 trademark attempts for a title, both of which were taken by other publishers.

made the transition to talkies. He is perhaps most famous for playing Three Musketeers villain Cardinal Richelieu four times and briefly appearing in Republic’s iconic serial Zorro’s Fighting Legion.

The William Witney and John English directed production started filming on December 23, 1940, and ended 39 days later, on January 31, 1941. The rushed production was typical of the movie serial, directors often speeding through one take with the cast and then moving on. It took something as serious as freakish inclement weather to delay the filming by a few days. With a script as thick as a “Los Angeles telephone directory” (according to Coghlan), and twelve chapters to film, it required the cast and crew to put in long workdays. The long hours are most likely why they went with a baby-faced adult like Coghlan rather than an actual child actor.

The preview for The Adventures of Captain Marvel opened with the explosion of Billy’s first transformation into the good Captain, white font in a Whiz Comics style announcing the hyperbole of a dozen “startling never-to-be-forgotten episodes!” Kids were treated to Captain Marvel walking into a hail of gunfire and flying to tackle two goons. It was hailed as Republic’s “outstanding serial of all time.”

Captain Marvel opens in the Valley of the Tomb where the Malcolm Expedition has arrived to learn the secrets of the ancient Scorpion Dynasty. An army of natives attacks the five-man expedition, along with young Billy Batson and his pal Whitey, Malcolm’s secretary Betty, and turbanned native guide Taj. The quick action is put on hold when Taj gets the army’s leader, Ramin, to call the attack off on a technicality. The Scorpio volcano will erupt when the white man has defiled the tombs, and it has yet to erupt, making the attack unwarranted and dishonorable.

While in a tomb, the stern Taj (played with stoic mastery by white actor John Davidson) warns Malcolm and company about not heeding a warning plaque which guards something that is to stay unseen “for all time.” Billy Batson, the only level headed one in the bunch, refuses to go further, as he feels it would be disrespectful. “Billy is the wisest of us all…I shall follow his example,” Taj declares as he remains in the anteroom of the tomb.

What is the secret hidden behind the plaque, one that will haunt everyone for a dozen chapters? A metal scorpion with five lenses that, when positioned in line with a shaft of sunlight, forms a destructive ray. The expedition finds this out the hard way when they set off a small avalanche in the tomb and are trapped.

Meanwhile Billy, looking for safe ground, is led into a hidden door that shuts behind him and traps him in a room with a large in-wall sarcophagus. The scorpion-embossed coffin opens to reveal – Shazam, the ancient wizard! He knows Billy’s name (by virtue of being all-wise and ancient), and bestows upon Billy the powers of Captain Marvel. Showing Billy a magical inscription on the wall (which magically turns from an ancient cuneiform into English) Shazam reveals the source of Captain Marvel’s power: nothing less than abilities borrowed from Solomon, Hercules, Atlas, Zeus, Achilles, and Mercury!

Of course, they’re all Greek deities and demigods, with the exception of the Biblical Solomon, and oddly not located outside of Greece. We can guess that Billy wasn’t up enough on his ancient mythology, or was just too polite to question the old wizard.

After following the old wizard’s order and saying his name, Billy is ensconced in a flash and puff of smoke and transformed

39

CHAPTER 2: The Adventures of Captain Marvel

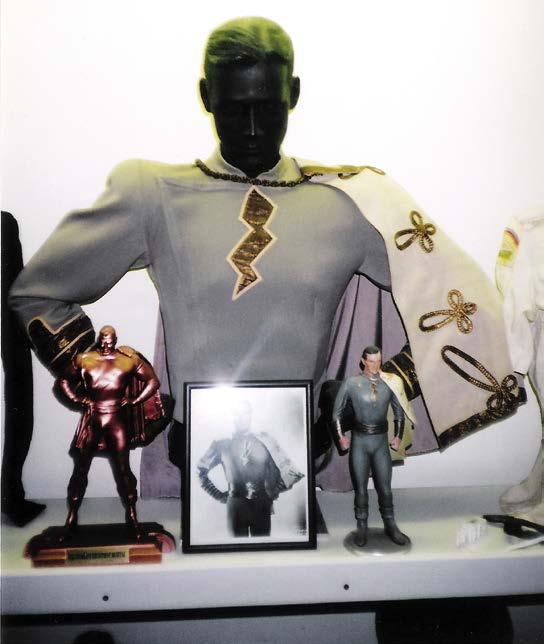

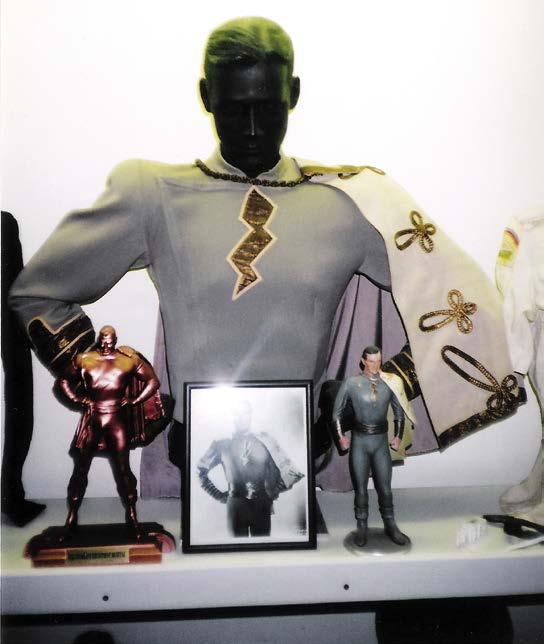

The Captain Marvel suit, on display at Bob Burns’s private museum.

Photo courtesy of Glen Cadigan.

Bit the Bullet

The decision to scrap a Bulletman serial came from a fear of further litigation: National may claim Bulletman’s ability to fly was further infringement on Superman. National would settle with Republic in December, 1949 for $15,000 prior to the case going to court for breach of contract.

The copyright suit against Fawcett and Republic was another matter: federal judge John Coxe’s 1950 decision off the 1948 hearing claimed National abandoned the Superman copyright when the McClure Newspaper Syndicate failed to put proper copyright notice on some of the newspaper strips. After Republic was awarded $1,000 by Coxe, National appealed the decision.

On August 30, 1951, Circuit Judge Learned Hand (ironically, brother of August, from 1941) reversed the previous dismissal, and cited the National Comics lawsuit against Victor Fox for creating Wonder Man as precedent. Also, because McClure was not a direct affiliate of National, he didn’t feel it was just to hold National accountable for abandoning the copyright. Before further hearings could be scheduled, Fawcett and Republic settled out of court in May, 1952. Fawcett Publications, ready to stop publishing comic books anyway, agreed to cease publication of all things Captain Marvel.

Republic was required to pay National $15,000 and not release the Captain Marvel serial to television or create sequels. Since the original agreement’s theatrical rights were still honored, it allowed Republic to eventually release The Adventures of Captain Marvel on home video— something unforeseen in the 1950s.

The serial format lent itself to superhero comics for the first time with “The Monster Society of Evil,” a serialized story that started in March, 1943’s Captain Marvel Adventures #22 and ran a staggering twenty-five issues to May, 1945’s #46.

When Captain Marvel fights Captain Nazi over the crown jewels of a princess from the Middle East, his enemy is working at the behest of a mysterious voice broadcast from a fortress in outer space. Each chapter pits Captain Marvel against a different villain on his path to uncovering the true mastermind, and it’s something not even his wildest dreams could conjure: the hyper intelligent, bespectacled alien worm Mr. Mind! Written by Otto Binder and with pencils by C.C. Beck, it was a tour-de-force in superhero storytelling and set the stage for creating a long-running continuity in monthly comics.

Created during wartime, “Monster Society” is rife with racial stereotypes, including Japanese agents and Billy Batson’s Black sidekick Steamboat. When DC Comics was about to publish an overdue hardcover collection in 2019, they canceled it over those dated and harmful depictions.

The final Captain Marvel comic to hit the stands was The Marvel Family #89 in late 1953. The cover features a young boy, in a plaid shirt, looking at the blank silhouettes of Captain Marvel, Captain Marvel Jr., and Mary Marvel. “Holy Moley!” he calls out. “What happened to the Marvel Family?”

45

CHAPTER 2: The Adventures of Captain Marvel

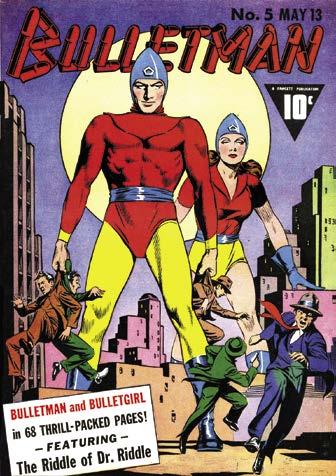

(top) This ad in Master Comics #14 (May, 1941) announces the serial to readers. (bottom) Bulletman and Bulletgirl’s serial hopes were dashed before they could begin. Art by Mac Raboy.

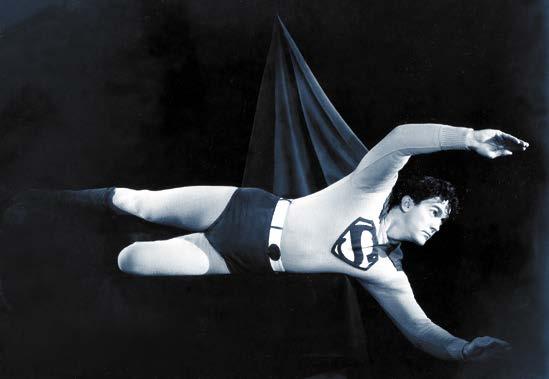

The Superman theatrical cartoons are firm testimony to the success of the newborn superhero genre and came hot on the heels of Captain Marvel’s big screen debut. Produced by the pioneering Fleischer Brothers, their influence can still be felt over eighty years later.

The seeds for the Fleischer Studio were planted in 1915, when Max Fleischer, then the editor of Popular Science Monthly , invented the Rotoscope. This device allows an animator to trace actual film onto an animation cel, creating more lifelike and naturalistic moment. It is the first example of motion capture technology in film.

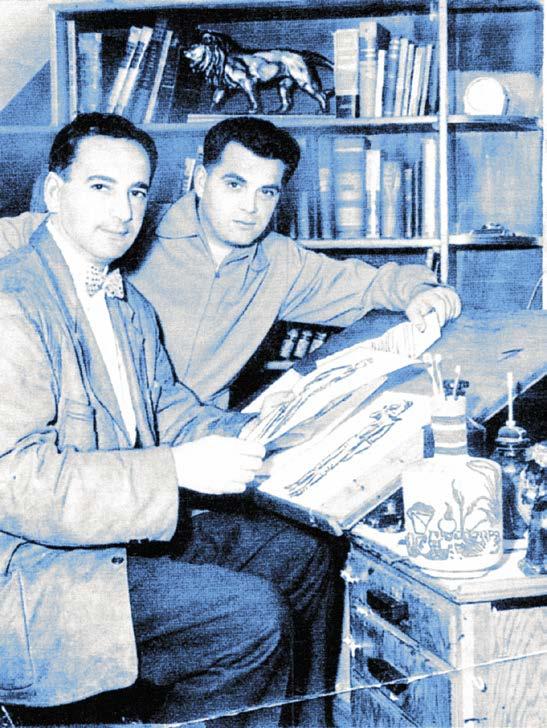

All three Fleischer brothers, Max, Joe, and Dave, arrived in the United States with their European immigrant parents in 1887. With Joe’s mechanical aptitude, and with Dave posing as the subject of their inaugural cartoon, Koko the Clown, they successfully combined the naturalistic movements of film with the expressiveness of animation. Koko became the guinea pig for the brothers’ experiments in animation, combining traditional animation footage and clay to create a collage effect. Oftentimes, the brothers themselves “starred” in the live-action segments.

Partnering with John Bray, an animator who was packaging work for Paramount Studios, the Fleischers produced a series of cartoons (titled Out of the Inkwell), starting in 1919. By 1921, Max and Dave broke off as their own studio, with Max handling the business side and Dave the creative. Whether

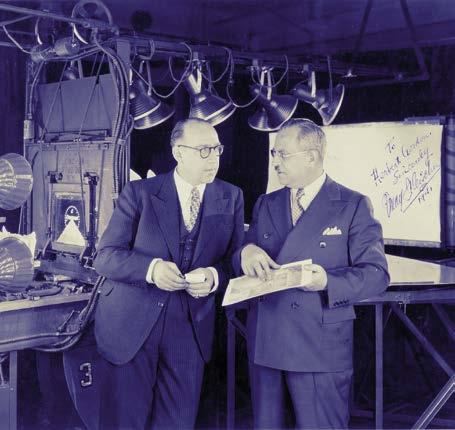

CHAPTER 3: Fleischer Cartoons 49

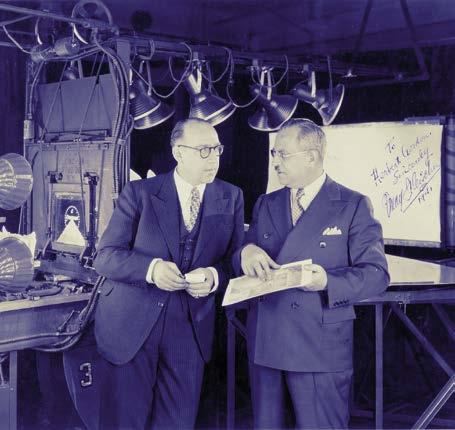

Max and Dave Fleischer in the studio.

Koko and his dog, Fitz are beheaded by a crazy sheik, or running against the backdrop of a live circus to find a missing girl, these “Inkwell Imps” (as they were soon called) always wound back up in the ink bottle in the end.

Aside from the revolutionary rotoscope technology, the Fleischers also used “in-betweeners,” or staff artists to draw the “in-between” motion of the animated figures. Many of the future Golden Age comic book artists, including Jack Kirby and Sheldon Mayer, got their start as in-betweeners at Fleischer.

The Fleischers held their own in the sound transition, debuting Betty Boop in the 1930 cartoon Dizzy Dishes . Betty Boop was a sexy and flapperish creation of the Fleischers who, with her short dresses and garter belts was deemed too sexy after the censorship codes of the 1930s. They also licensed Popeye the Sailor man from King Features Syndicate for a string of highly acclaimed short cartoons. Many of the Popeye and Betty Boop cartoons used Fleischer’s trademark and revolutionary 3-D approach, the Three-Dimensional Set Back. The machine was simply a camera set with a pane of glass that an animation cell could be hung against (there were pegs over the glass, and corresponding registration holes on each cell), and the glass was set before a model/ miniature placed on a turntable set against a backdrop. This way, the cameramen could move the scenery along a track or the turntable, the drawn cartoon figures “imposed” via the glass, to create the illusion of movement. As a result of this device, the cartoons combined live-action models with animated figures, giving the cartoons a sense of foreground, midground, and background…and an eerie and effective sense of perspective and realism.

A 1930s color documentary shows Max Fleischer in the camera room, referred to as “Popeye’s filmland poppa”. At this point in his life, Max is a distinguished man of thick build, wearing a gray suit and glasses, his temples smartly grayed and a neatly trimmed moustache on his upper lip. In contrast, Dave was once described as “short, mild-mannered…Easy to approach and confident.”

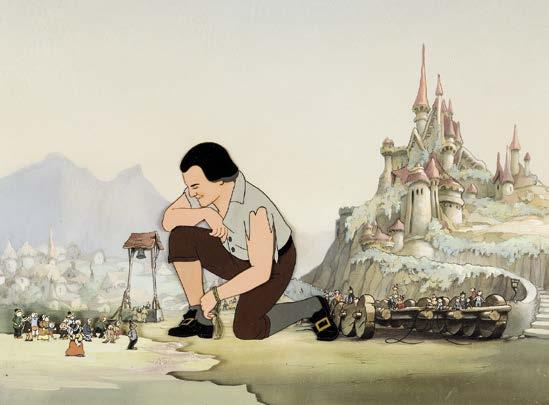

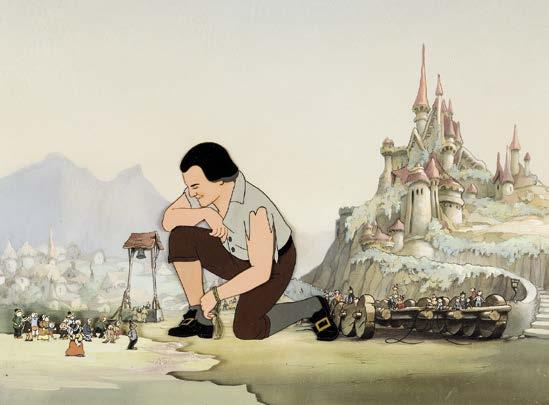

By 1939, the Fleischers used their rotoscope and 3-D techniques to produce the classic animated adaptation of Gulliver’s Travels, their first feature that was an attempt to compete with Disney after the release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs two years before.

Straight Outta Krypton

Republic lost the Superman license a second time because Paramount was apparently willing to outbid them. When Paramount asked the Fleischers how much they’d need to produce Superman, the disinterested pair gave the exorbitant budget to produce the first short

“I couldn’t figure out how to make Superman look right without spending a lot of money,” Dave Fleischer said. “I told they’d have to spend $90,000 on each one.”

This was three times the cost of an average Popeye short, and the brothers were shocked when Paramount agreed to it. Every following short was budgeted at $100,000 per roughly ten-minute cartoon. One cost-saving measure was to draw forms based on blocks and wedges rather than circles and ovals.

Superman, only a couple years after his debut, had become enough of an institution for National Comics publisher Harry Donenfeld to form Superman Inc. Sales of Action Comics doubled within nine months, and Superman was given his own

CLIFFHANGER! Cinematic Superheroes of the Serials: 1941–1952

50

(left) Koko gives a sad farewell to Betty Boop’s Snow-White (1933). (right, top and bottom) 1939’s Gulliver’s Travels was the Fleischers’ foray into feature length.

(clockwise from top left) The iconic Fleischer Superman. A drawing for the episode “Terror on the Midway.” An animation cel from the debut short, also known as “The Mad Scientist.” A key photo from the debut.

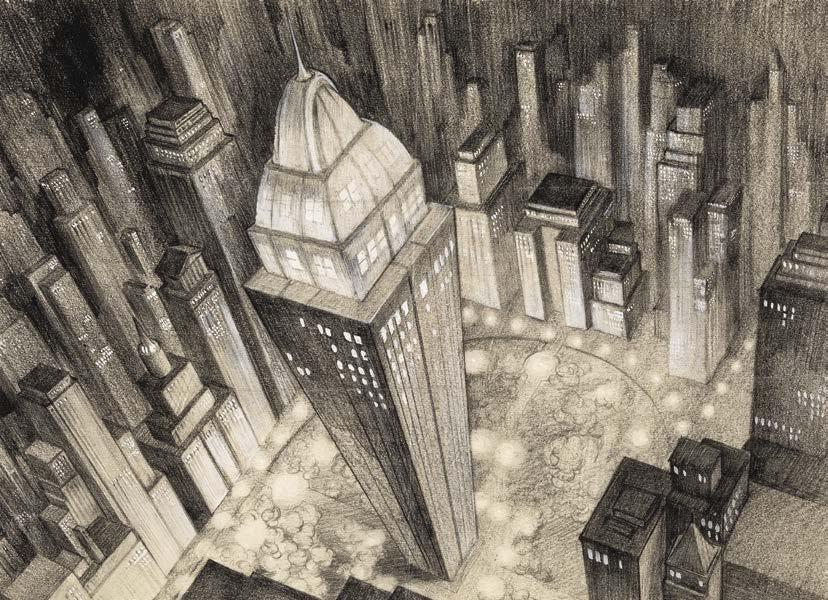

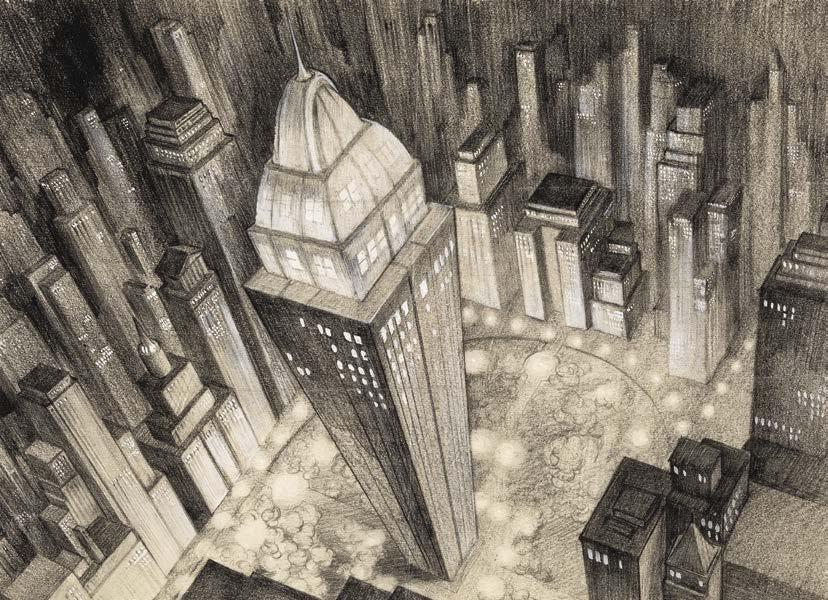

(bottom) Metropolis was an art deco dream in the Fleischer Superman cartoons.

CLIFFHANGER! Cinematic Superheroes of the Serials: 1941–1952

52

Up until America’s entrance into the war, motion picture producers refrained from identifying countries with whom we were at war on the screen by specific name. However, now that there is no question as to who is our enemy, the film writers can bluntly name their enemies. And Republic’s new serial, “Spy Smasher”...is one of the first films in which Nazis are Nazis.

—Republic Press book for Spy Smasher

1941 was an eventful year for William Witney; John English temporarily left movie serials behind for the greener pastures of Republic’s motion picture wing, leaving him to work without the partner he developed a system of serial creation with.

And Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, officially pulling America into World War II. Witney had already been approached about a commission to work with a marine photographic unit out of Washington, D.C.

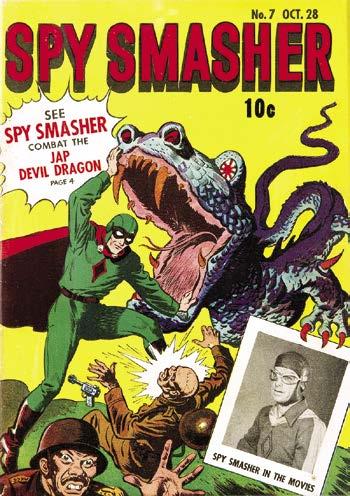

The combination of Captain Marvel’s earlier success and the oncoming storm that was World War II had Republic taking on another Fawcett Publications character, the begoggled Spy Smasher.

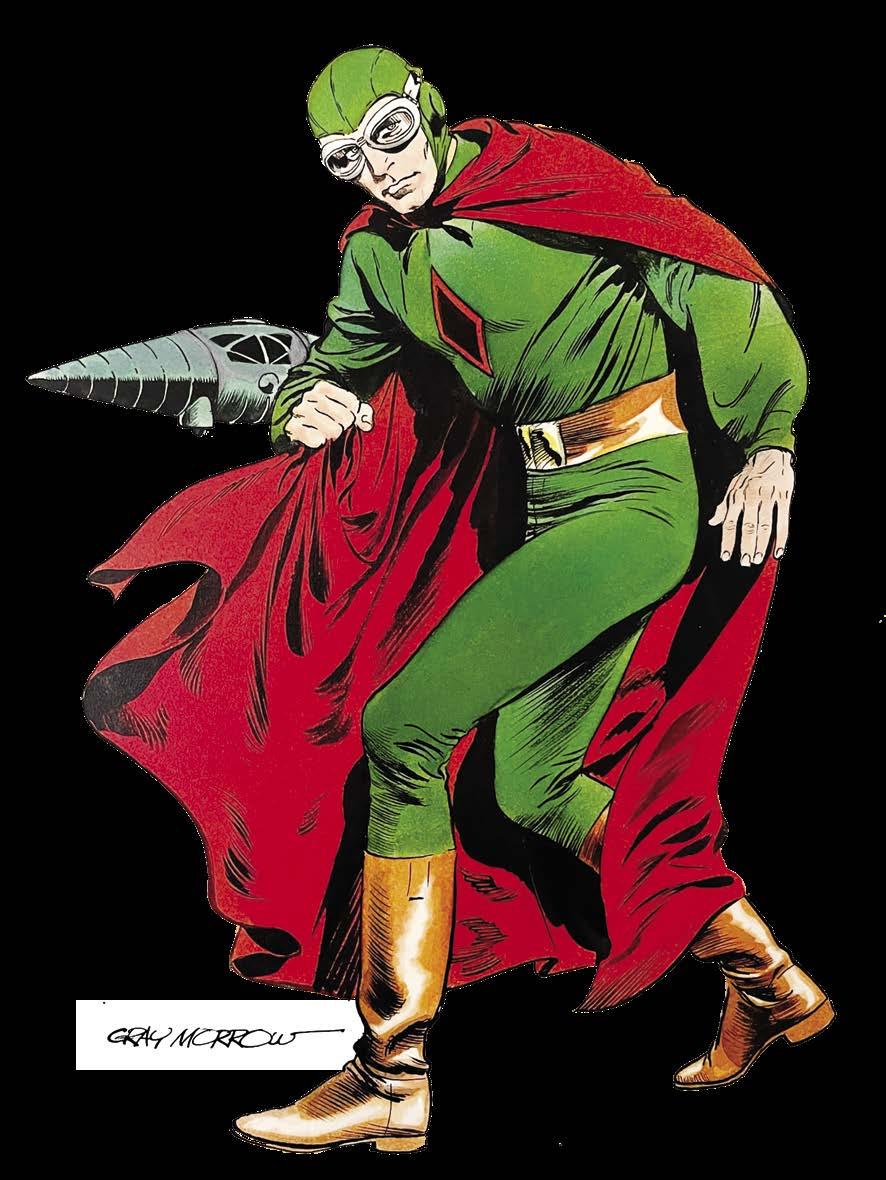

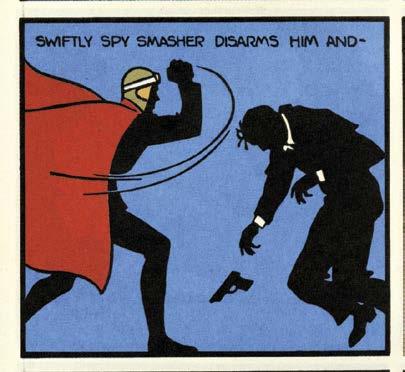

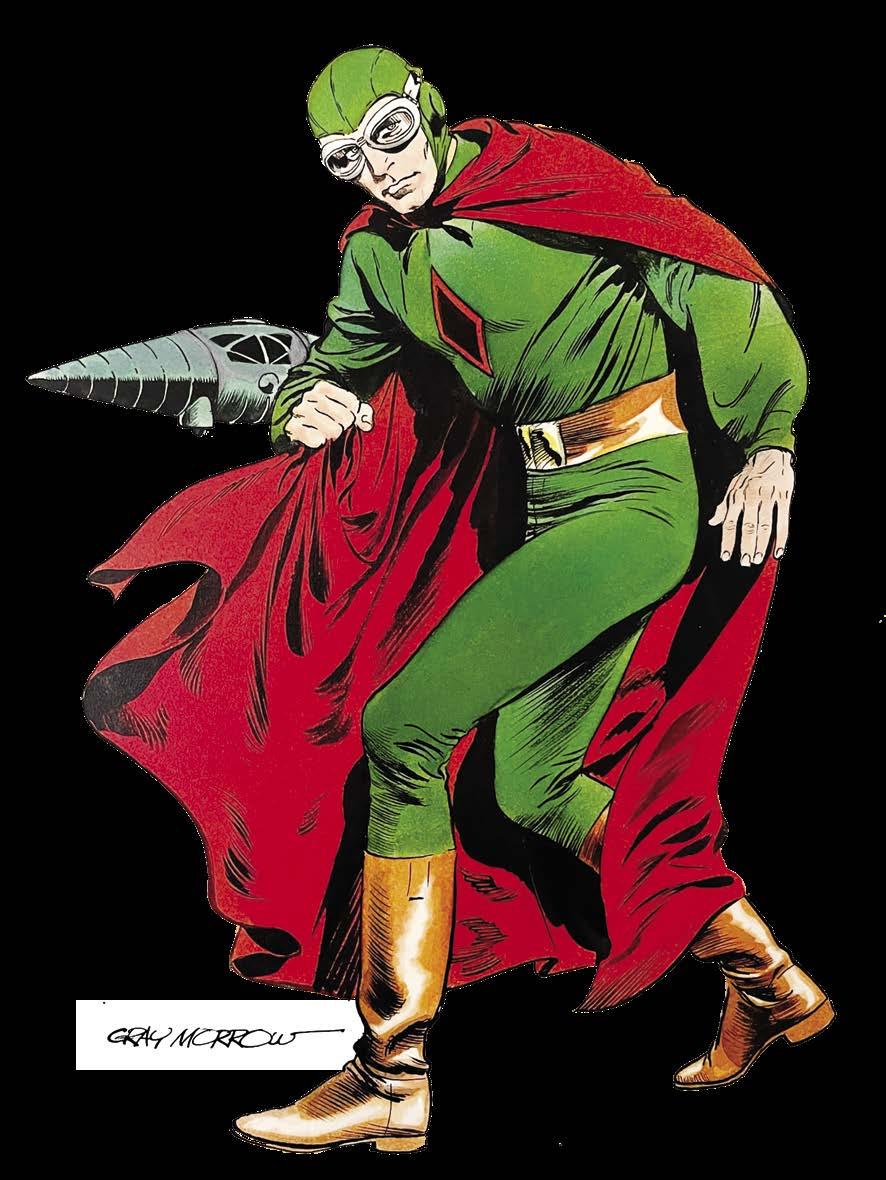

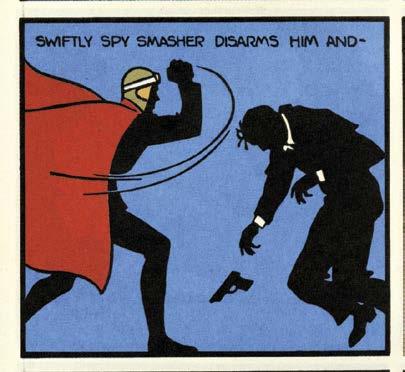

Spy Smasher, along with Captain Marvel, made his first appearance in Whiz Comics #2. Created by Bill Parker and drawn by C.C. Beck more realistically than his Captain Marvel, Virginia sportsman Alan Armstrong (who Beck modeled off famous actor Errol Flynn) donned an aviator helmet with goggles, long cape, and a flight suit to become the mostly silhouetted Spy Smasher. Creeping around in the shadows in his first appearance, Spy Smasher was more somber than the headlining Big Red Cheese, foiling foreign agent The Mask in a noir world.

“Spy Smasher”’s beauty was in the intense and heavy shadows rendered by Beck, contrasted with bright primary colors. Even though Spy Smasher flew around in the “Gyrosub,” that little bit of fantasy seemed grounded in relation to the character’s mortality and semirealistic foes. When the strip fell into the hands of artist Pete Costanza (a regular inker of Beck’s work) by 1941, it lost the romance of the earlier Beck strip. The stylized-by-Beck aviator uniform became a more standard superhero costume at the tip of Costanza’s pen.

CHAPTER 4: Spy Smasher 55

Spy Smasher even went toe-to-toe with Captain Marvel in March, 1941’s Whiz Comics #15. The Mask, hobbling around on crutches from their last encounter, captures Spy Smasher and zaps him with his Brainograph, ordering him to “work

Luckily for both Spy Smasher and America, the brainwashing wore off in time for his own title with the cover date of June, 1941.

AGAINST

THE GOVERNMENT!…KILL

all the generals!” In a shocking moment, the programming proves itself a bit too well, as Spy Smasher clobbers Mask to death, and then goes on his mission of sabotage. Captain Marvel comes onto the scene in the next issue, drawn by Beck, and the titans tussle for three more, with Beck drawing the Marvel chapters, with Smasher’s by Charles Sultan. The result was a mish-mash of styles with Beck’s mastery of design and simplicity far beyond Sultan’s straightforward superhero work.

The Adventures of Captain Marvel was still in the midst of its run when Universal Studios made Republic an offer for both Spy Smasher and Bulletman at $5,000. Pleased with Adventures of Captain Marvel, Fawcett’s E.J. Smithson gave Republic’s William Saal a take-it-or-leave-it-on-the-spot offer to license both at $1,500 on June 11, 1941. Continuing the mutual relationship was a no-brainer for both parties.

Bulletman was police criminologist Jim Barr, who used a brainpower-enhancing formula and gravity-defying bulletlike helmet to fight criminalsby slugging or essentially headbutting them. Launching into the air and flying like his namesake, Bulletman was also impervious to bullets (thanks, as well, to his helmet).

CLIFFHANGER! Cinematic Superheroes of the Serials: 1941–1952

56

(left) Gray Morrow’s personal illustration of Spy Smasher. Scan courtesy of Marc Svennson. (right) Spy Smasher fights from the shadows, from his debut in Whiz Comics #2. Art by C.C. Beck.

(top to bottom) Kane Richmond and Marguerite Chapman strike a publicity pose. Stills of Richmond as Spy Smasher.

After Republic passed on Bulletman, for fear his ability to fly would leave them vulnerable to further legal shenanigans from National Comics, it was knocked down to a $750 option for Spy Smasher alone. They signed the final contract on August 28, and it came in at an unprecedented 42 pages. Republic was obligated to use Spy Smasher’s name and costume, and it also came with a decade-long option for a serial. For $100 a week, Harrison Carter was hired to write the 15,000 word treatment that would then go to the serial’s writing team.

After completion of the first draft estimating script (written to figure the budget), producer Hiram S. “Bunny” Brown left Republic to serve in the Army Signal Corps and was replaced with William O’Sullivan. It may have been behind John English’s desire to leave the serial unit and finally move into film, leaving Witney to solo direct with a producer he wasn’t personally fond of either. His condition for O’Sullivan was that he had the cooperation of the producer in directing the film. For $175 a week, Witney directed the estimated $120,000 production over the winter, with exceptions for the holidays.

“The costume he wore made me laugh,” Witney recalled, but Republic was contractually bound to have Spy Smasher wear it in the serial. To boot, the script “had put in the kitchen sink and the toilet.” Spy Smasher quite easily could have been the worst serial Witney ever directed.

Despite the director’s coldness towards Spy Smasher, he delivered a standout serial that holds up surprisingly well. The production benefits from a perfect leading man type in Kane Richmond, Witney’s dynamism behind the camera, and some of Republic’s best fight scenes.

Pure Kane Sugar

Kane Richmond had all the features of a popular leading man: he was strapping and muscular at six feet, granite-jawed, steelyeyed, and an amazingly good actor. Richmond was born as Fred W. Bowditch in Minneapolis on December 23, 1906. Fred grew to excel in sports, and graduated from the University of Minnesota.

Working as a film booker for the TiffanyStahl Motion Picture Exchange in Minneapolis when 24, Richmond became the west coast representative for Columbia Pictures. He was noticed by an executive from Universal, who got him a screen test. The Republic press book for Spy Smasher put it this way:

Kane Richmond.

CHAPTER 4: Spy Smasher 57

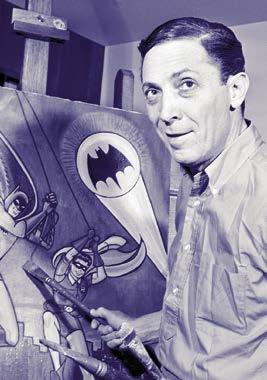

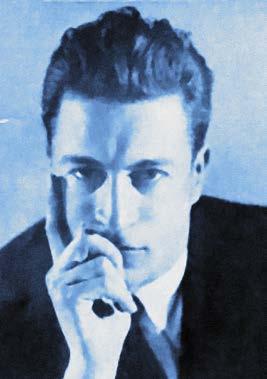

Batman was a pulp response to Superman’s science fiction roots, created by an ambitious young cartoonist and his uncredited writing partner. If Siegel and Shuster’s story was an inspiring one of brotherhood, Bob Kane and Bill Finger’s was a cautionary tale of opportunism.

Born Robert Kahn in the Bronx in 1916, Bob Kane’s father was an engraver for the New York Daily News. Bob attended DeWitt Clinton High with future comics genius Will Eisner. Changing his name to the more Americanized “Bob Kane” at age 18 (one rumor has it that it was in honor of serial star Kane Richmond), his cartoonist dreams weren’t to even become good – Bob was more intent on attaining a level of comic strip artist celebrity so he could live the easy life.

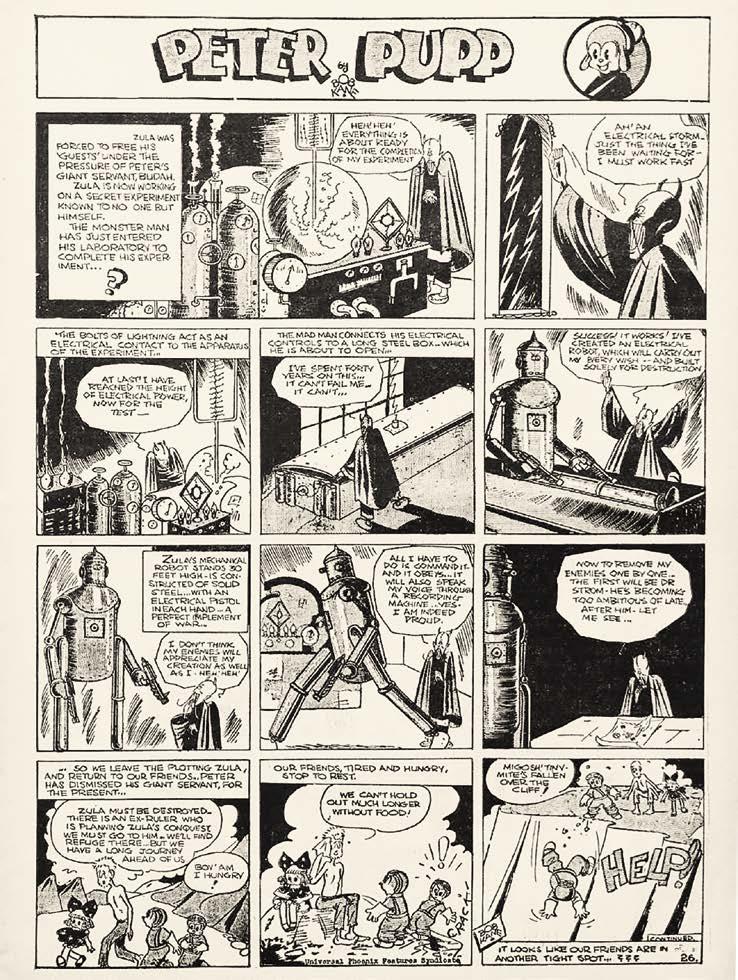

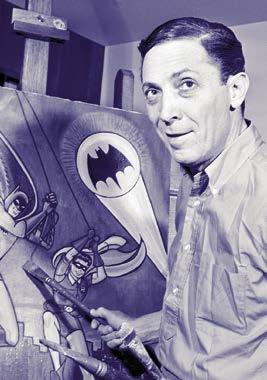

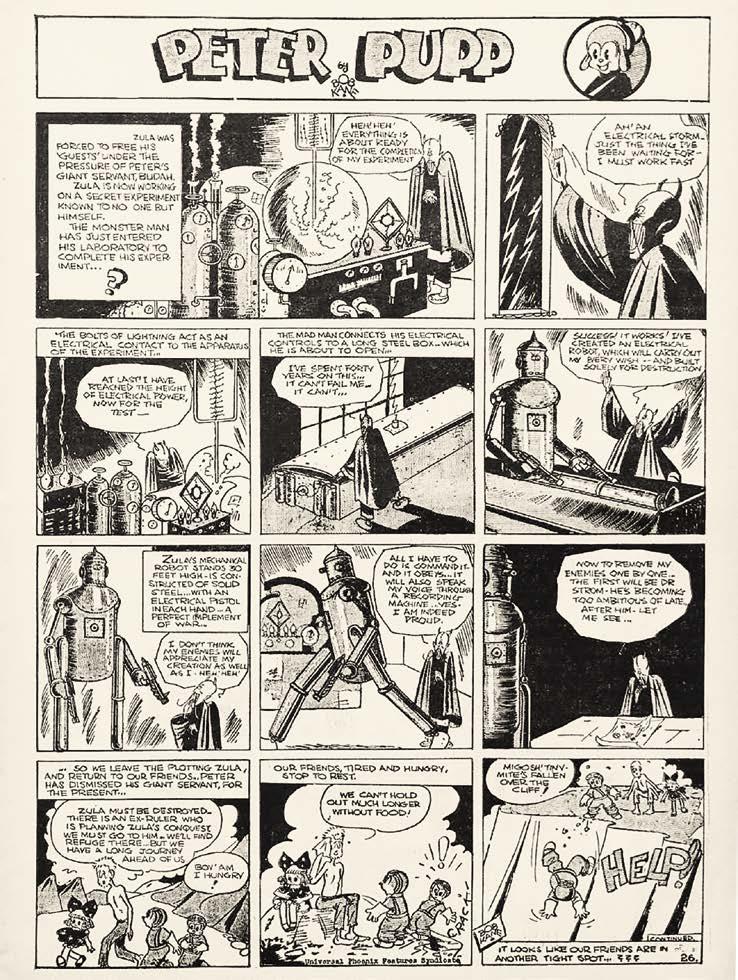

Kane’s work was in more of a “Bigfoot” vein – meaning he drew in what today would be considered a “cartoony” style – and even once worked as an in-betweener at the Fleischer Studios. When Eisner and his business partner Jerry Iger formed the first comic book studio, Bob came on board and drew anthropomorphic dog strip “Peter Pupp,” and a few strips for Detective Comics and their sister publisher, All-American Comics: “Ginger Snap”, “Oscar the Gumshoe”, and “Professor Doolittle”. Kane’s Milt Caniff-inspired Rusty and His Pals is the bridge that carried him from funny stuff to dark action, a transition that carried him through the rest of his career.

Looking at a 1938 “Peter Pupp” from Jumbo Comics #5, the strip has a German Expressionist by way of Walt Disney feel. As The Monster Man, Zula (a cloaked figure wearing a wide-toothed devil mask with a droopy moustache), cavorts amongst electrical globe and other Universal monster movie devices in his lab, the fruits of 40 years of work, a 30-foot robot with dual death rays in each hand stands tall by the sixth panel. The awkward lettering of Zula’s dialogue, the spare room in

CHAPTER 5: Batman 65

Bob Kane.

his balloons, and the weird Caniff-ish use of blacks hint at the atmosphere that will later infect the Batman strip.

With the wildfire-like success of Superman, Kane approached Detective editor Vin Sullivan about making the switch from funny animal to costumed hero. Sullivan asked Kane to produce a new hero on a Friday, on the condition that he have it by that Monday. Kane, hungry to break out of the $40 a week fill-in existence he’d known for a few years, enlisted the help of part-time writer Bill Finger, who had been ghostwriting “Clip Carson” and Rusty and Her Pals. The differences between the two are uncanny: the free-wheeling, suave Kane was out chasing skirts at age 22 while the brilliant Finger was supporting his wife and son by selling shoes at age 24.

“Bill was a very delicate guy, and I don’t use that word in a pejorative sense,” Irwin Hasen, the artist who created Wildcat with Finger, recalled. “He was a very good-looking, handsome, little guy, a short man. I’m 5’2” and he was maybe 5’4”. He was a very elegant dressed man, erudite and tragic. I use that word in a very sad sense, because Bill was always behind on his work,

but he was always behind the 8-ball, and always late on his deadlines, always in debt, but the sweetest, gentlest guy you’d want to meet, and such a creative guy.”

“Bob may have been a fine talent,” Batman assistant and ghost artist Jerry Robinson laughed. “But Bill became my friend, and my culture mentor. I was a really young kid, 17, just out of high school and in New York for the first time. He took me, for the first time, to the Met, to MOMA, to foreign films, to the Village. That was exciting.”

The debate over who contributed what to the initial Batman concept apparently entails Kane designing a Superman-like blonde man in a domino mask and red tights with stiff bat-like wings attached to his back. Kane claimed for years that he had been influenced by everything from Douglas Fairbanks, Jr to Leonardo Da Vinci’s ornithopter to a 1930 film titled The Bat Whispers, which features a villain in a head-to-toe bat costume.

Finger’s recollection, in historian and comics legend Jim Steranko’s The Steranko History of Comics reads that Kane’s initial Batman drawing “looked very much like Superman

Bob Kane’s early work on “Peter Pupp” showed a competency in his use of shadow. It would serve him well for Batman.

CLIFFHANGER! Cinematic Superheroes of the Serials: 1941–1952

66

with kind of ... reddish tights, I believe, with boots ... no gloves, no gauntlets ... with a small domino mask, swinging on a rope. He had two stiff wings that were sticking out, looking like bat wings. And under it was a big sign ... Batman.”

Other reports have the character’s original name as “Bird-Man,” but were changed at Finger’s suggestion.

“Batman was very crude at the beginning,” Kane said in 1989. “He had stiff bat wings stuck behind his shoulders; he looked like a bat, actually. But I showed Vincent Sullivan my first crude sketches of Batman that Monday. He loved it and said, ‘Okay, let’s go!’”

Contributions made by Finger likely included the distinctive bat cowl, the bat emblem on the chest, the scalloped gloves, turning the stiff wings into a bat-like cape, and even naming the alter ego Bruce Wayne, apparently in honor of Kane himself.

Without Finger’s knowledge, Kane struck a long-term deal with Vin Sullivan that gave himself more of a stake in the character than Siegel and Shuster had with Superman. The terms, while mostly speculation, involved a set page rate and amount of Batman pages owed to National a month, as well as a sole ownership credit for Kane on Batman It would be an early example of Kane’s doing things without the knowledge of his collaborators: for years, he kept each of his “ghost” artists from one another, and allegedly did very little drawing on the strip itself.

“He was a very vapid, shallow, egotistical man who was lucky enough to have his father insist that he gets his rights to Batman,” Hasen noted. “It’s one of those strokes of luck. The publishers even regretted it! The whole thing was a lie.”

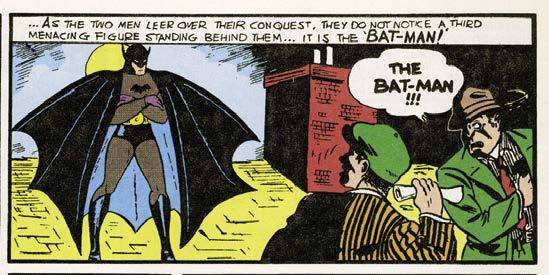

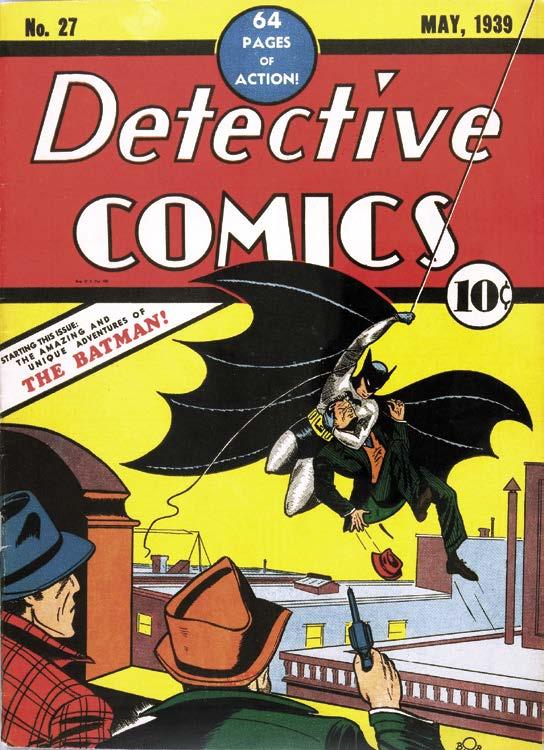

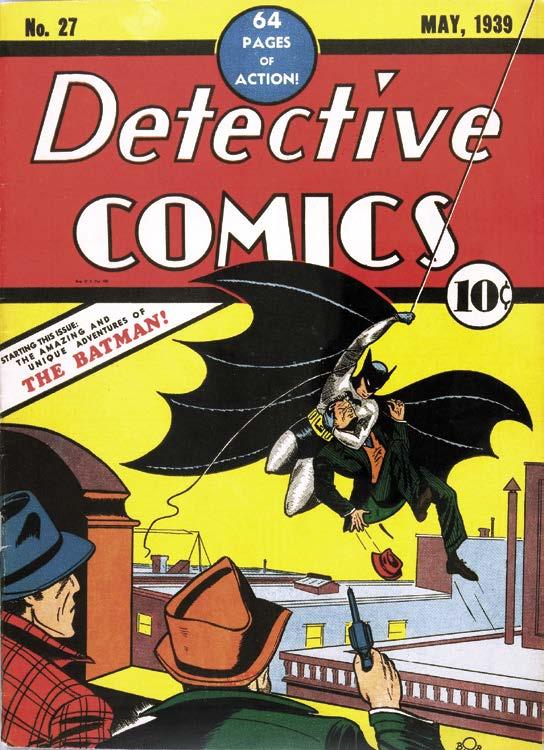

Effective Comics

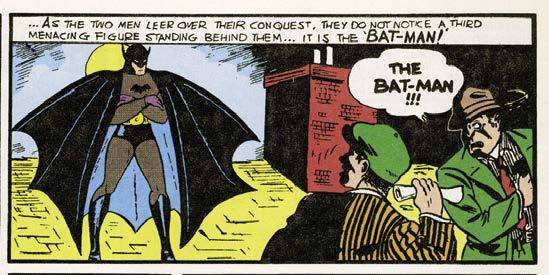

Detective Comics #27 in the Spring of 1939 featured a black and gray-clad, pointy-eared hero stiffly swinging over the city, a thug head locked under left arm, and more frightened thugs in the foreground of the rooftop this dark hero was about to alight upon. Kane’s cover art was possibly more dramatic than Shuster’s Action Comics #1 cover, but it wasn’t entirely original: Batman’s pose was swiped from Alex Raymond’s the January 17, 1934 Flash Gordon daily strip. The blond space adventurer had gone from swinging around on Mongo to whizzing by modern city rooftops in a batsuit.

The debut story, “The Case of the Chemical Crime Syndicate,” starred a much more dark and grim Batman than today. He wasn’t a superhero, but a pulp character in a garish costume.

It opens in the home of Commissioner Gordon as he entertains his socialite friend Bruce Wayne. They’re reclining opposite one another, respectively smoking cigar and pipe, when Gordon mentions this mysterious “Bat-Man.” The

CHAPTER 5: Batman 67

Bob Kane’s cover was a swipe of Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon, but at least he picked an iconic pose. Batman makes his stiff-winged debut. Story by Bill Finger, art by Bob Kane.

Bill Finger.

became a mainstay of comics, possessing of all the trappings of a pulp hero like The Shadow), while Finger’s origin gave the character a vulnerability and manic bent that hinted at a complex figure. As much fun as Superman was, he lacked the psychological underpinnings of the Dark Knight.

Finger, prone to drinking and late scripts, was sometimes replaced in the script-writing department by attorney-turned-writer Gardner Fox, who contributed elements such as the Batarang and Batman’s distinctive crime-fighting gear to the mythos. Fox was first brought to Detective via his old pal Vin Sullivan, and was soon writing several features for both them and sister company All-American. He co-created mainstays the Flash, Hawkman, and Dr. Fate, and was the main writer on All-American’s superhero team the Justice Society of All-Star Comics.

Batman lightened up when his sidekick Robin, a young acrobat whose parents were murdered by a gangster, was introduced in Detective Comics #38 (April, 1940). The idea for Robin came from either Bill Finger on his own, or Bob Kane, or perhaps it was at Kane’s insistence, and designed by Jerry Robinson. Robin was created to not only give Batman someone to talk to, but also to lighten up the strip and provide a character for the kid readers to connect with.

The Boy Wonder sparked a flurry of boy sidekick imitators: Captain America had the eerily similar Bucky, Human Torch had Toro, Blue Beetle had Sparky, Sandman had Sandy…Sidekicks proliferated in the Golden Age because of

Batman gained his own comic book title later that year, swinging across a yellow-skied Gotham with Robin on the first cover. Fighting an array of Dick Tracy-ish villains like the Joker and Hugo Strange in the now-dubbed Gotham City, Batman became the heavy-hitter both Vin Sullivan and Bob Kane were hoping for.

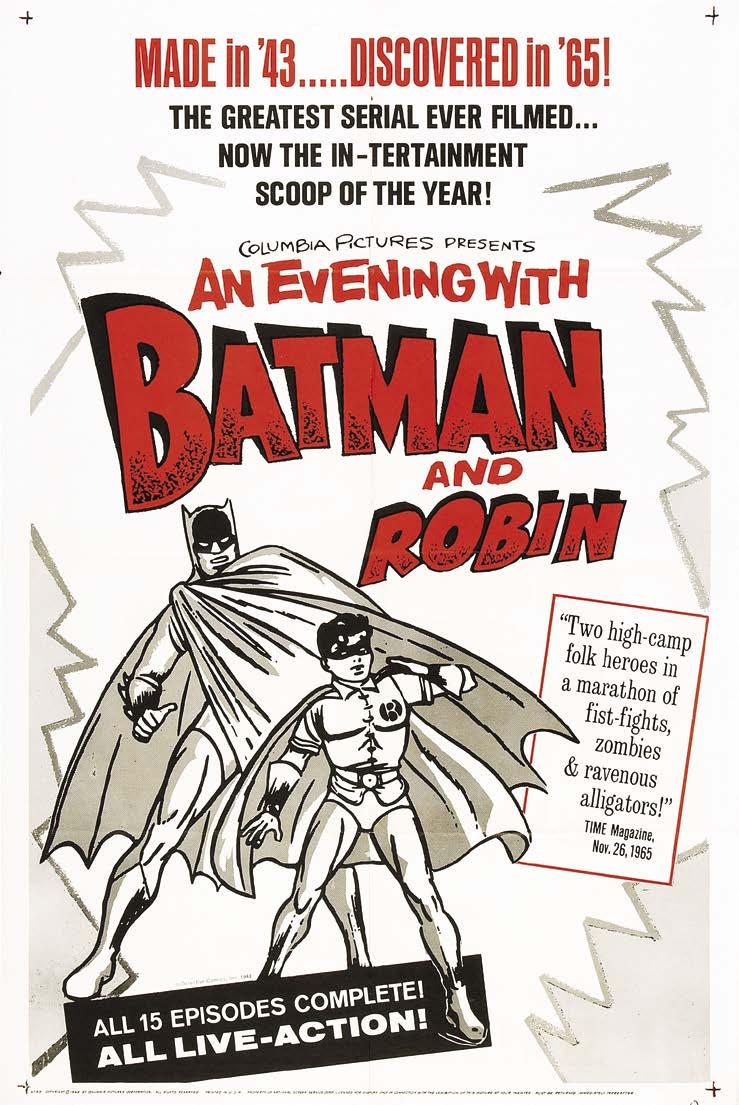

Columbia, or more specifically producer Rudolph Flotow, picked up the movie serial during wartime for a 1943 release. Since censorship codes kept Batman from being the vigilante crimefighter of the comics, he was now a crimefighter for Uncle Sam.

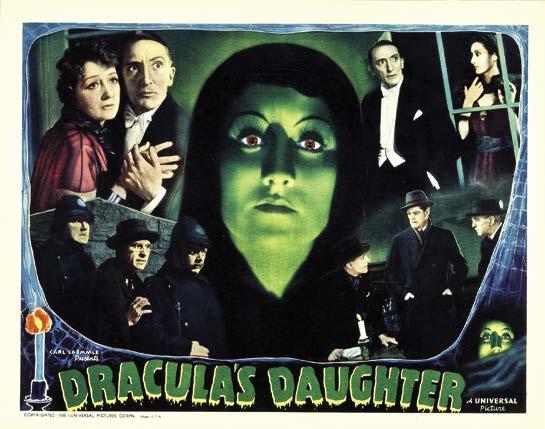

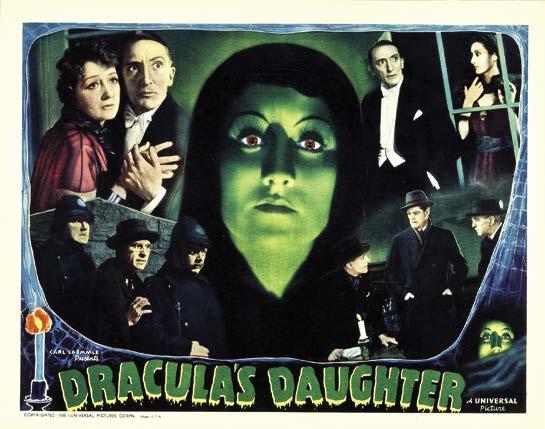

The director, Lambert Hillyer, had directed the critically acclaimed Dracula’s in 1936. This sequel to the Bela Lugosi classic has the Count’s daughter struggling to break free of her vampiric curse. It is atmospheric, beautifully shot, full of pathos, and in some ways superior to Tod Browning’s original Dracula. , however, was a different animal.

(top) Lewis Wilson in the cape and cowl. (bottom left) Director Lambert Hillyer’s Dracula’s Daughter remains a hidden gem. (bottom right) The U.S.S. Shaw, bombed during the attack on Pearl Harbor. Photo courtesy the Library of Congress.

CLIFFHANGER! Cinematic Superheroes of the Serials: 1941–1952

70

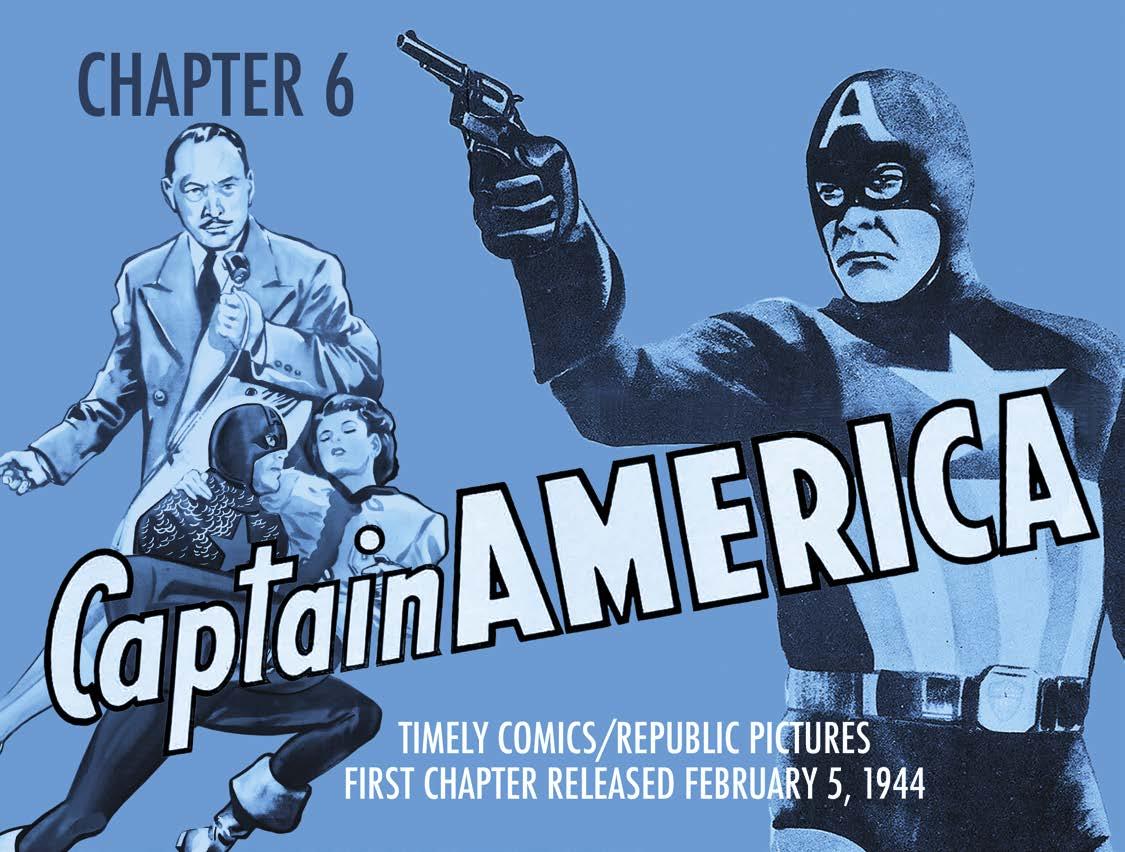

“Iwas in the service, and the first I heard about it was when I was in Bolivar, and I saw it at a local theater,” Captain America creator Joe Simon remembered a day in 1944. “I didn’t go in to see it, but I saw a marquee that read Captain America. It’s a bitter feeling to see your character in the movie when your name isn’t on it.”

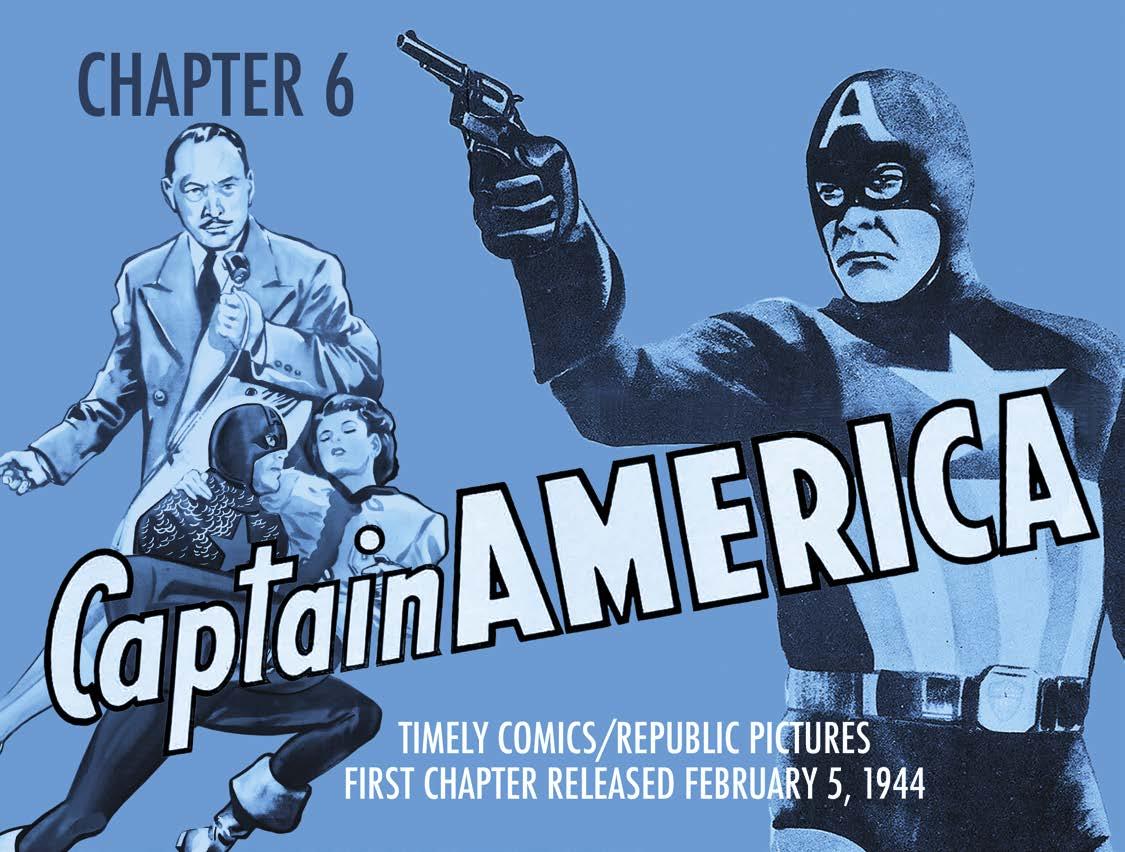

Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, the powerhouse creative duo of the Golden Age, gave Timely Comics (the company that is now Marvel Comics) their first star in the red, white and blue-clad avenger…and wound up black and blue from the whole ordeal. The Republicproduced serial of 1943 was the first of what grew to be many live-action misfires in adapting the Sentinel of Liberty to film, but is technically one of the better serials produced.

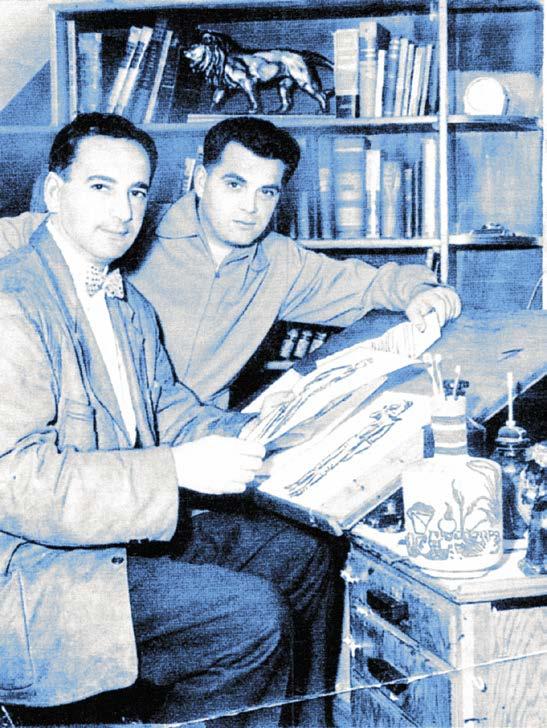

The Simon and Kirby team is legendary.

The team met while working for Fox Comics, a third-rate comic book “publisher” run by the notorious Victor Fox. Simon was an editor, while Kirby was one of the bullpen artists, churning out work like third tier superhero The Blue Beetle

“I was very young, 24, I think,” Simon recalled. “Kirby was even younger, and was working at the bullpen at Fox. He found out that I was doing this extra work, and asked if he could come over and work with me. I said ‘Sure,’ since I had more than I could handle. I had to get letterers and inkers to help me meet my schedule.”

The two were an odd pairing: Simon a tailor’s son who grew up in upstate Rochester, while Kirby (born Jacob Kurtzberg) was raised in the tenements of New York’s Lower East Side. Simon was tall and business-minded, while Kirby was a short scrapper who talked little in comparison. It’s likely they balanced each other out, creatively and professionally.

Operating out of an office in the Empire State Building, 32 year-old pulp publisher Martin Goodman, like dozens of others, took a stab at the new comics field. Starting in 1932, the pulp fan started with his Marvel Science Stories and Marvel Tales, as well as more successful Western and crime pulps, under the imprint name Red Circle.

CHAPTER 6: Captain America 81

Goodman commissioned comic book editor and packager Lloyd Jacquet’s shop Funnies, Inc. to create Marvel Comics #1 in October, 1939. His big stars were the initially volatile Human Torch, an android completely engulfed in flame, and Namor the Sub-Mariner, a pointy-eared half human, half Atlantean prince who angrily wreaked havoc on the people of New York City. Timely Comics held true to their pulp roots, with heroes who meted out justice from the other end of a gun or at the end of a superpowered fist. Goodman needed a star superhero and, after commissioning work from him, Joe Simon was the man to give him one.

“We’d have the main character be second banana to the villain, and that’s how Captain America came out,” Simon recalled in 2009. “I picked Adolf Hitler as the ideal villain. He had everything that Americans hated, and he was a clown with the funny moustache, yet guys were ready to jump out of planes for him.

He was the first choice, and his antagonist would have to be our hero, and we’d put a flag on the guy and have Captain America.”

Joe and Jack worked after-hours in Simon’s small office nearby, mostly on science fiction comic Blue Bolt for Novelty Press. Simon’s claim is that he’d already started on Captain America, story and all, when Kirby came onboard.

“I’d done the story right on the boards, the roughs, and the presentations and everything else. I brought Kirby in, and he did his own wonderful work on it. He tightened up the pencils and did his own penciling. We worked very closely together on it. …That’s how the first issue of Captain America was done; from my little office on West 45th Street, after hours from Fox Comics.”

It was then, Simon claims, that Captain America was submitted to Timely Comics, where Goodman bought the superhero from the duo and appointed Simon editor and Kirby art director.

82

CLIFFHANGER! Cinematic Superheroes of the Serials: 1941–1952

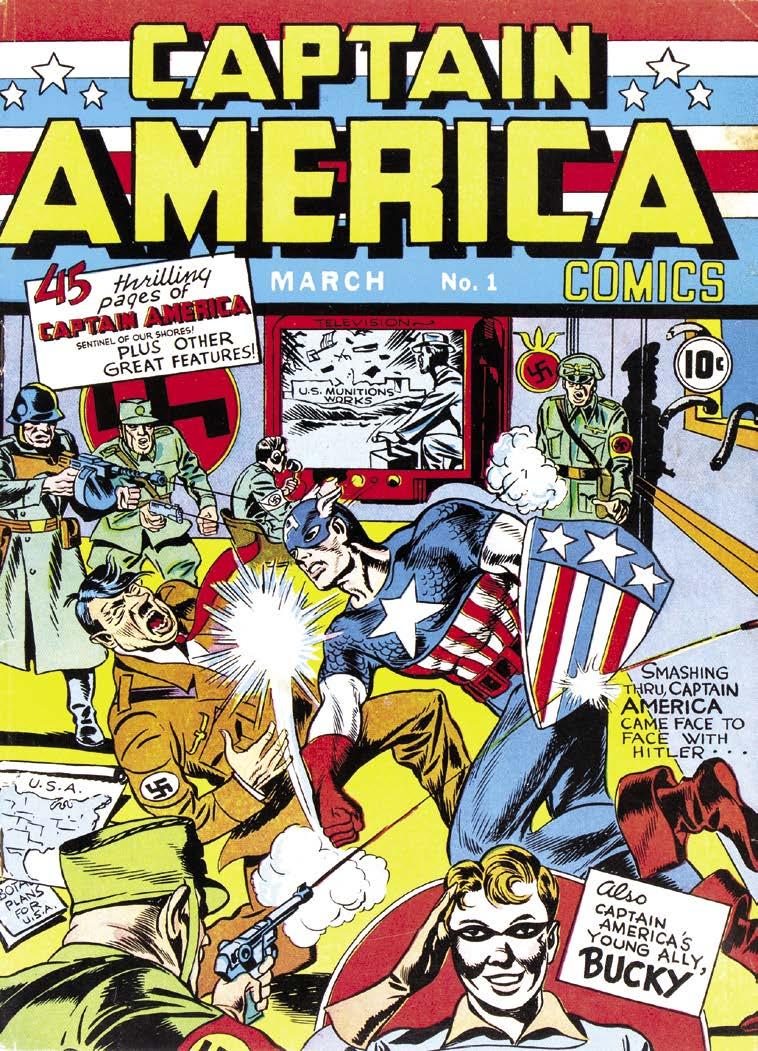

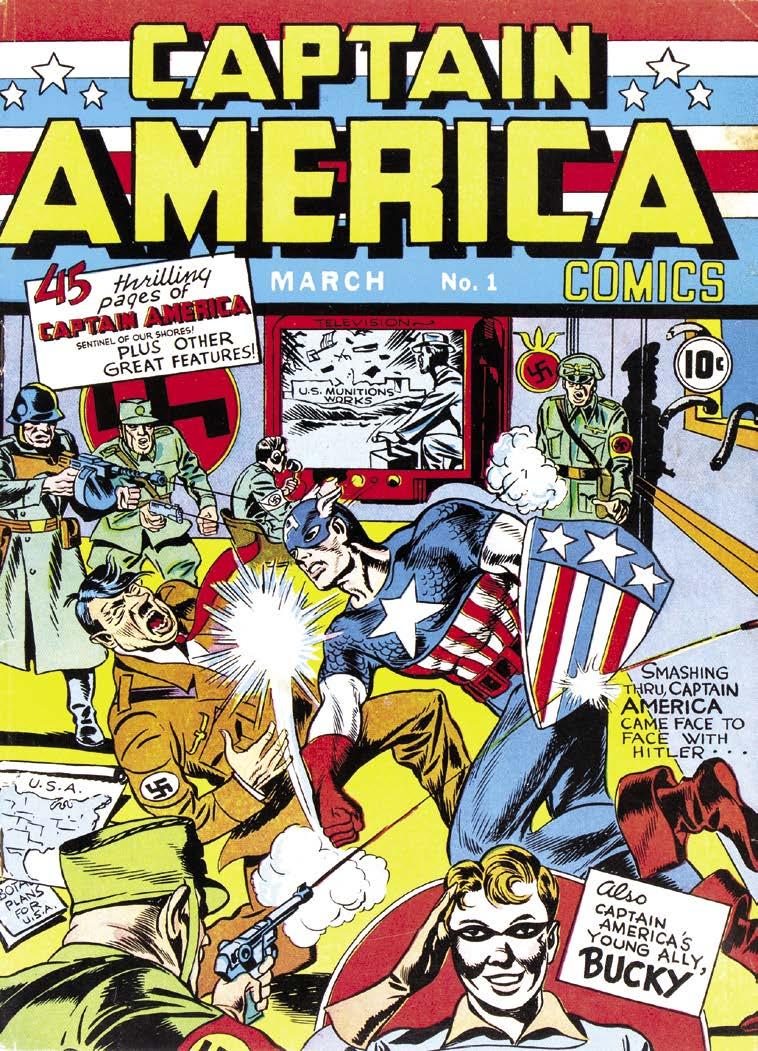

Captain America’s Nazi-busting cover debut! Art by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby

The legendary team of Simon and Kirby

Captain America Comics #1 came out with a March 1941 cover date, and hit the stands around December of 1940. While Captain America wasn’t the first patriotic hero (MLJ’s The Shield predated him), he was the first superhero to premiere straight into his own #1 issue.

In an eerie moment of prescience, Simon and Kirby had the flag-clad Cap slugging Adolph Hitler out on the cover, a good year before America entered the war after the December 7th bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese. It was the first time a patriotic superhero directly took on Nazism.

Red, White, and Blue-Blooded

The origin story in Captain America Comics #1 starts with a bang: the explosion of an American munitions factory by Fifth Columnists. Frustrated at the rampant Nazi sabotage, and the “army spotted with spies,” President Roosevelt informs two Army bigwigs that “something is being done.”

“What would you suggest?” he asks, in a metatextual moment, “A character out of the comic books? Perhaps The Human Torch in the army would solve our problem!”

Roosevelt sends the Army men to witness an experiment in a secret lab concealed behind the façade of a curio shop. In the surprisingly modern laboratory is a frail young man, inoculated with a “strange seething liquid” by Professor Reinstein…a liquid that soon swells his muscles and replicates millions of cells at a maddening speed. Standing in the frail man’s place is a blond powerhouse, a super-soldier – Captain America!

Before Reinstein can go any further, a Nazi spy within their midst kills him. Cap throws him against an electrical panel, and fries the spy to death. With the professor assassinated, the Super Soldier formula dies with him, leaving Captain America to take down the Axis Powers as a one-man army. By the end of the first chapter, Steve Rogers, Cap’s alter ego as an Army private, is caught changing into his Captain America costume by the camp mascot, Bucky Barnes.

In one of the oddest sidekick origins ever, Steve tells Bucky he’s now stuck becoming his partner since he’s in on his secret. After months of training, Bucky dons a blue and red costume with domino mask and also goes by Bucky when in costume.

Cap’s costume experienced some minor tweaks by the second issue. His mask now covered his neck, and his triangular shield was changed to a discus-like circle, that Cap threw at his enemies. Harry Goldwater, publisher of MLJ Comics (now known as Archie Comics), objected to similarities to their own patriotic hero The Shield, who wore a spade-like shield on his chest, similar in shape to Captain America’s. The discus-like shield ironically became both Cap’s trademark and weapon of choice.

Meanwhile, things weren’t going as well for Simon and Kirby. After Timely accountant Morris Coyne informed Simon that Timely was only paying them their royalties after first charging office expenses to Captain America ’s profits, they started looking elsewhere. Simon and Kirby found a home at Detective Comics while working at Timely.

“I was getting a royalty from Captain America, and it turns out that I was being lied to and cheated,” Simon said. “And I

resented it. Everybody wanted us in the business, so I made a deal with Jack Liebowitz at DC Comics. We had a contract with them, while we were working on issue #10. We decided to stay and finish that issue. Timely found out about the new deal, and the brothers surrounded us while we were working on Captain America Comics #10, and they fired us. They said ‘You better finish this issue [first]!’

“Martin Goodman came from a circulation background, along with Goldwater and some of those smaller publishers. [Timely] dealt with the business like, in my opinion, the creative people would definitely not turn out any profit. It turned out that they even took the credit away from us.”

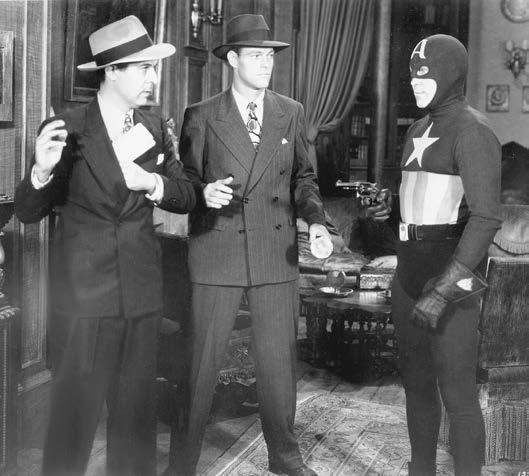

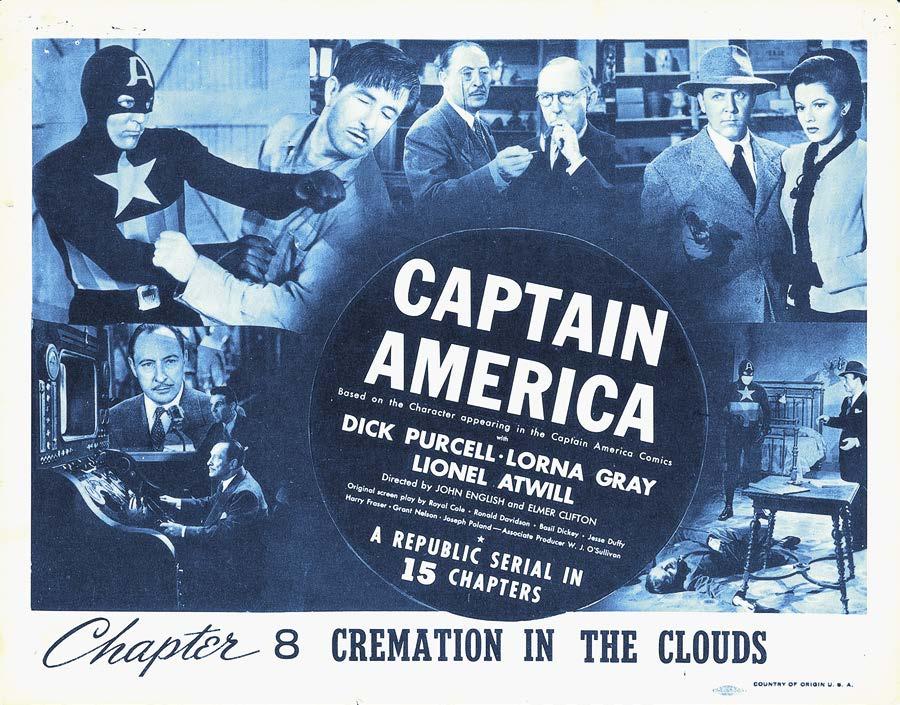

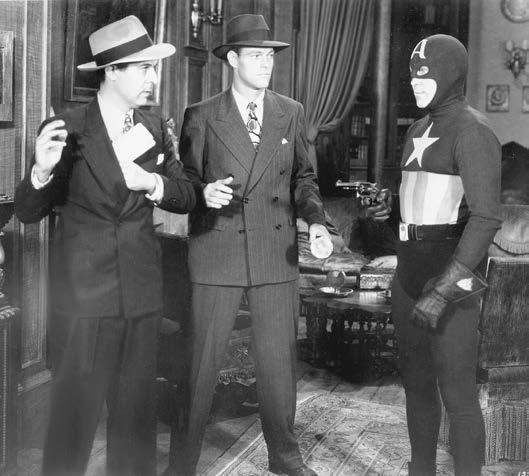

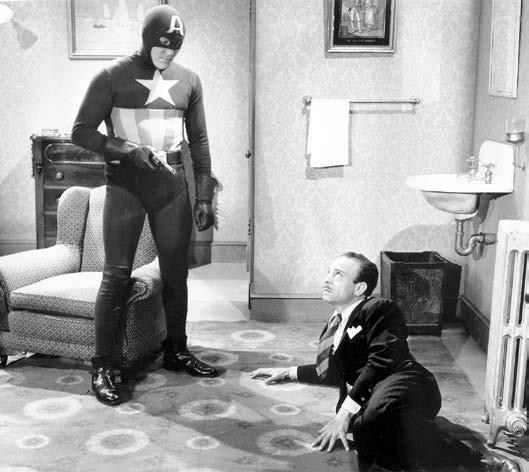

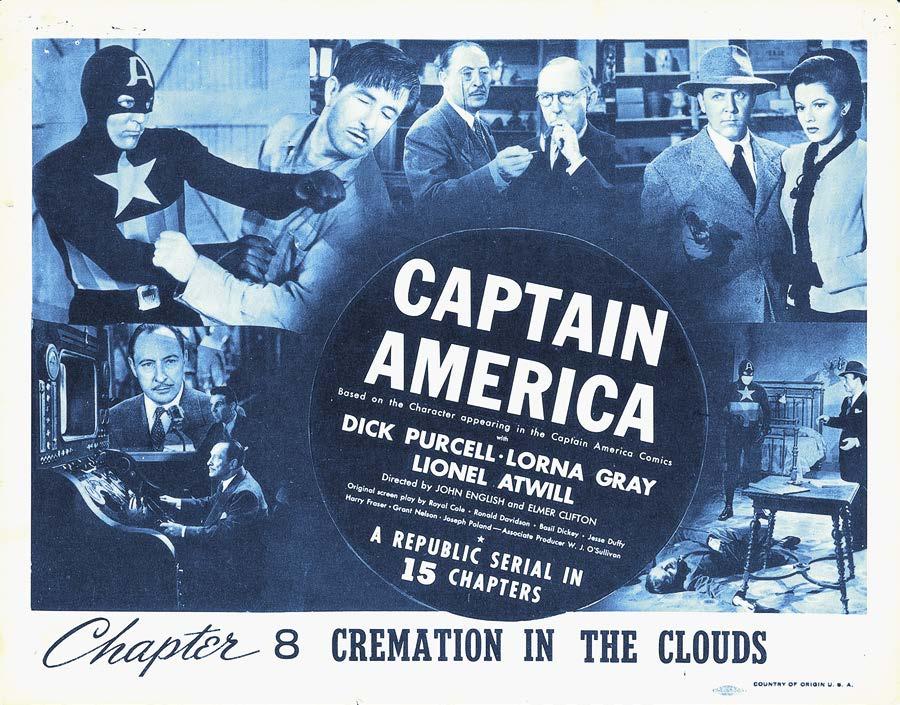

While the comic book industry was profiting from Captain America , Republic decided to give the Sentinel of Liberty a chance. They’d already enjoyed a degree of success with Spy Smasher , so it’s not surprising that they picked up another patriotic character. By 1943-44, however, they were ramping down making films for the war effort, and Captain America was left not fighting the Axis, but a criminal mastermind instead.

Dick Purcell was cast to play Captain America, and his alter ego of—Grant Gardner, District Attorney?

Historian and academic Raymond Stedman noted, in 1971:

The Simon and Kirby creation named Steve Rogers had to sneak away from his army base in story after story to fight the Axis baddies. It was an inconvenience equal to Clark Kent’s dressing problem. Grant Gardner... at least did not have to go AWOL constantly.

CHAPTER 6: Captain America 83

Captain America was his first serial role and likely taken out of necessity rather than choice.

John English was back in the serial division for Captain America, and this time teamed with a director whose work spanned back to the silent era.

Elmer Clifton’s early work as an actor include D.W. Griffith’s Birth of A Nation and Intolerance. He was determined to direct and was finally given a chance to direct a single scene in Intolerance : a double exposure of a girl’s hand playing a harp, with a character asleep on a floor.

With Griffith’s contract with the studio, Fine Arts, about to expire after two remaining films, Clifton made his case to production head Frank Woods, who gave him a chance to co-direct the Dorothy Gish vehicle Her Official Fathers, with Joe Henabery.

When he arrived on set, Henabery was not there, having come down with a bout of appendicitis. Clifton was left to direct the picture himself; it was the start of a successful silent film career for the handsome Elmer Clifton.

He cast future starlet Clara Bow in her first major film role for his 1922 Down to the Sea in Ships

86

CLIFFHANGER! Cinematic Superheroes of the Serials: 1941–1952

Elmer Clifton.

If anything, Captain America was dramatically lit, as seen in this still of Purcell.

Just a taste of the action in only one chapter of Captain America.

In 1926, he exuded upon what constitutes an epic picture to Motion Picture Magazine:

A picture may be an excellent illustration of good craftsmanship, as many of the so-called epic pictures of today are, and still not be epic if the great thought is lacking. For that is of primary importance. It is something more than art. It is something more than craftsmanship, or tricks of photography. It is the it of the picture, the spirit.

By the 1940s, Clifton was far from directing epic films, creating Poverty Row exploitation classics like Assassin of Youth and Gambling with Souls. Known for meltdowns on set and second-guessing himself, Captain America seems to be his only film serial, and it is surprisingly shot on par with a classic epic.

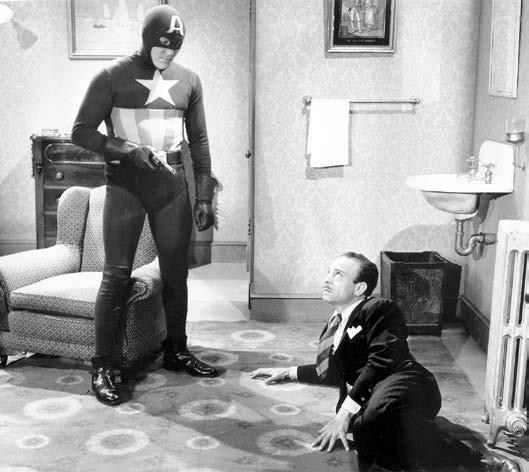

Captain America opens with the exploits of the main villain, establishing the threat of the film in the first chapter. In this case, it’s the Scarab, who alerts his victims with a small scarab that looks oddly like a spider. Drugged with a hypnotic serum, the Scarab drives the members of a Central American expedition to their deaths with his “Purple Death.”

It’s a darker opening than often seen in the serials, culminating with a gunshot suicide. Captain America is the closest to a superhero noir, as dark shadows creep around the sets, and most of the chapters have a decidedly urban setting.

D.A. Grant Gardner meets with the commissioner and mayor to devise a plan to stop the Scarab. the Scarab is really Dr. Maldor, who kills the expedition out of revenge for leaving

him out of the fame and wealth gained from the trip. His latest scheme is to get ahold of the destructive Thermodynamic Vibration Machine. Lorna Gray’s Gail Richards, the constantly imperiled assistant to the D.A., goes to the scientist’s lab asking to learn more about “the vibrator”. Soon after Gardner changes to Captain America and nearly has a building topple on top of him, via the unfortunately named Vibrator’s destructive rays, he manages to jump to an adjoining rooftop to safety.

There’s also yet another device that the Scarab needs to be kept from getting: the Electronic Firebolt, which is basically a giant flashlight that blows things up.

It only gets crazier as a multitude of McGuffins are thrown into the mix from chapter to chapter. It wasn’t unusual for serials to jump around, but they usually had some semblance of a main thread to follow and didn’t play hopscotch like Captain America, which was a train wreck of unrelated scientific devices, from robot trucks to Perpetual Life Machines.

And there are the shootouts, with Gardner regularly ducking behind armchairs and crates to match bullets against the thug of the chapter.

The Scarab, suddenly obsessed with the idea of eternal life, vows that he must have a Perpetual Life Machine that can bring the dead back to life. It manages to bring one of his goons back from the dead before being destroyed itself. Scarab, devoid of the Perpetual Life Machine and the scientist who invented it, merely shrugs the loss off and moves on to his next hare-brained scheme.

Things come around in a poor imitation of a full circle by the thirteenth chapter: Remember that Mayan expedition from early on? It turns out that one of the members, Hillman played by John Hamilton (who later played Daily Planet editor Perry White on The Adventures of Superman TV show), accidentally

CHAPTER 6: Captain America 87

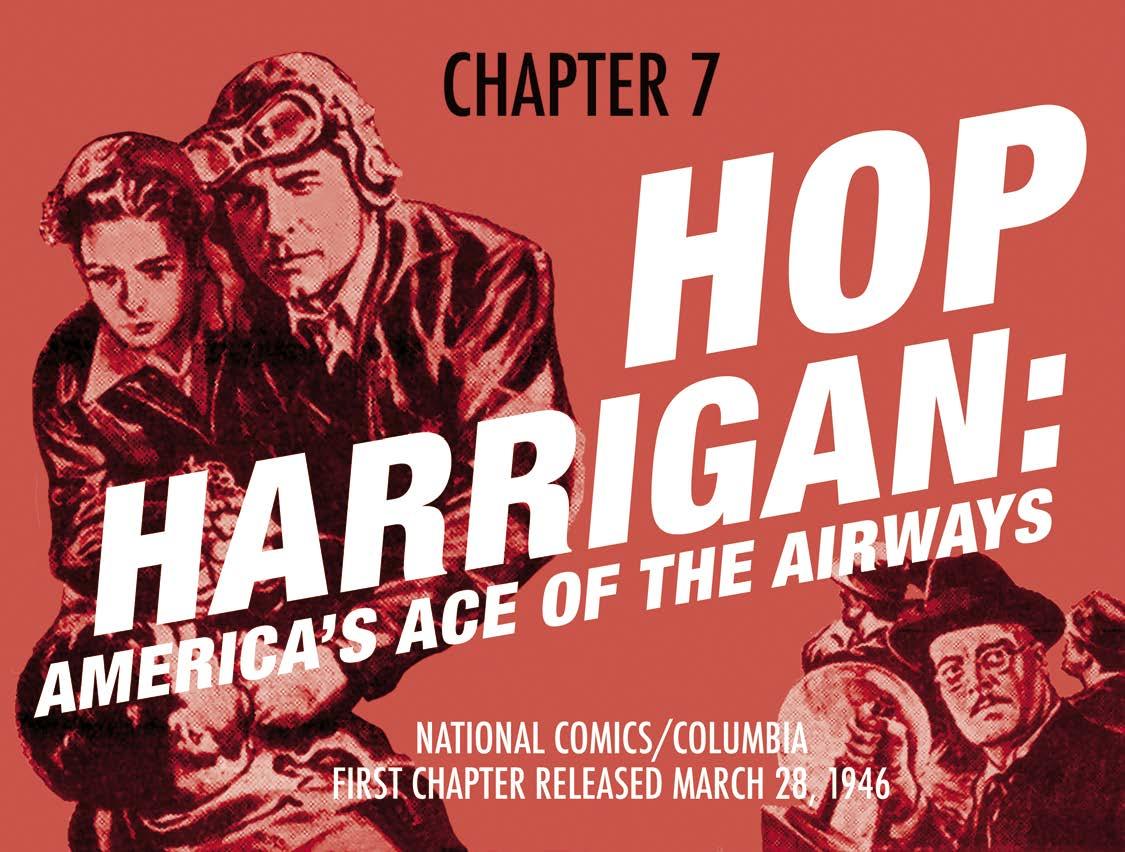

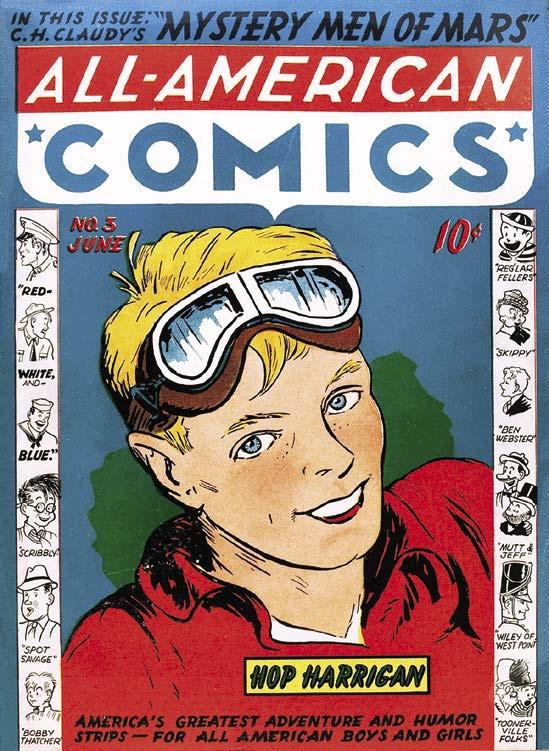

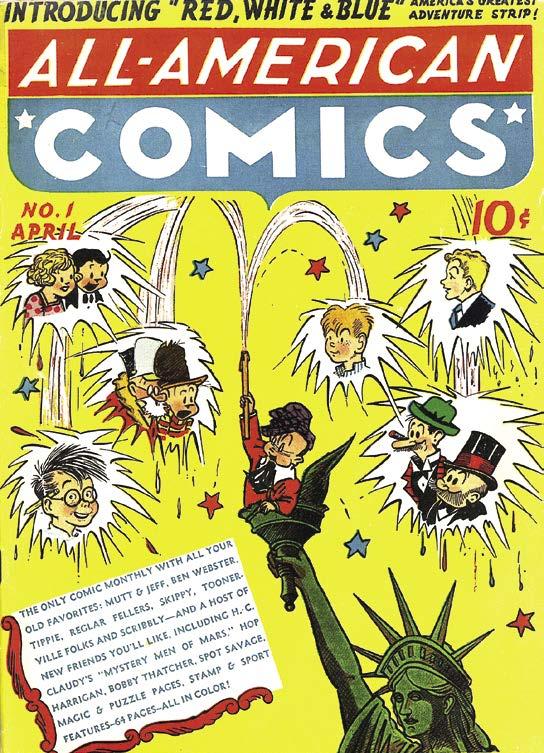

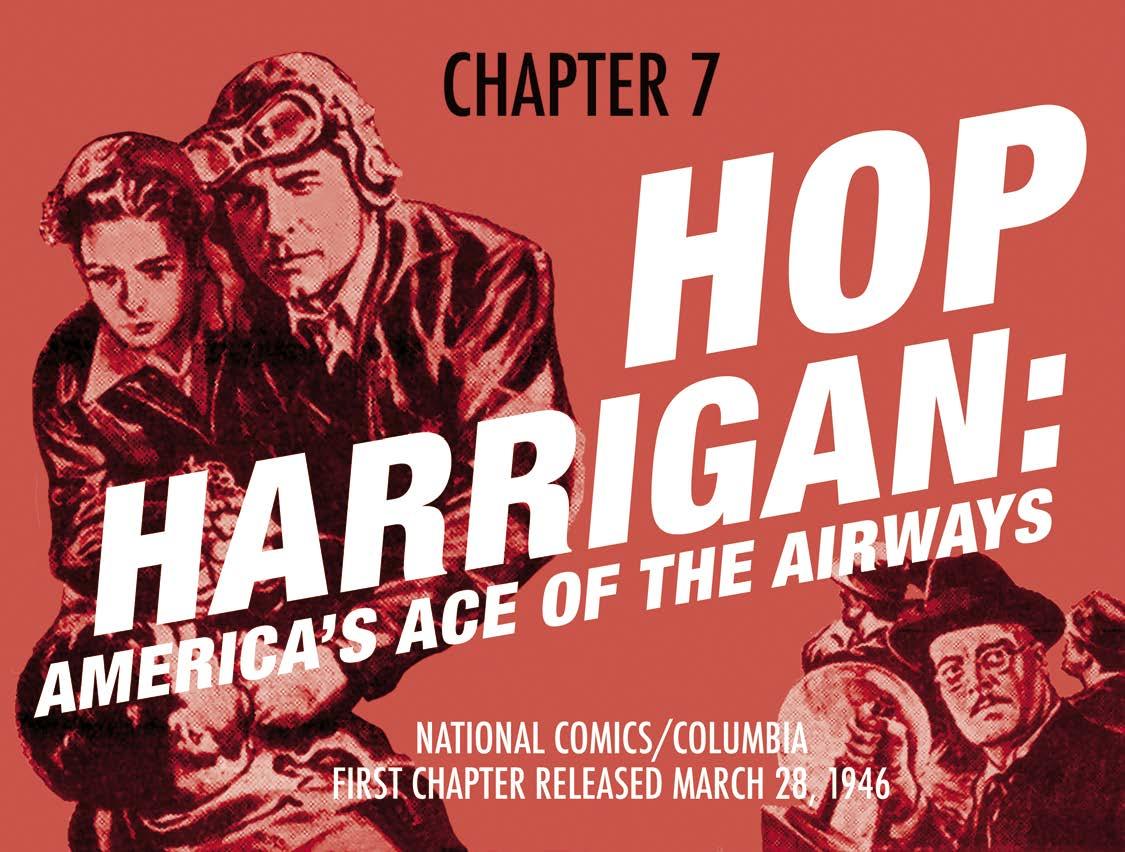

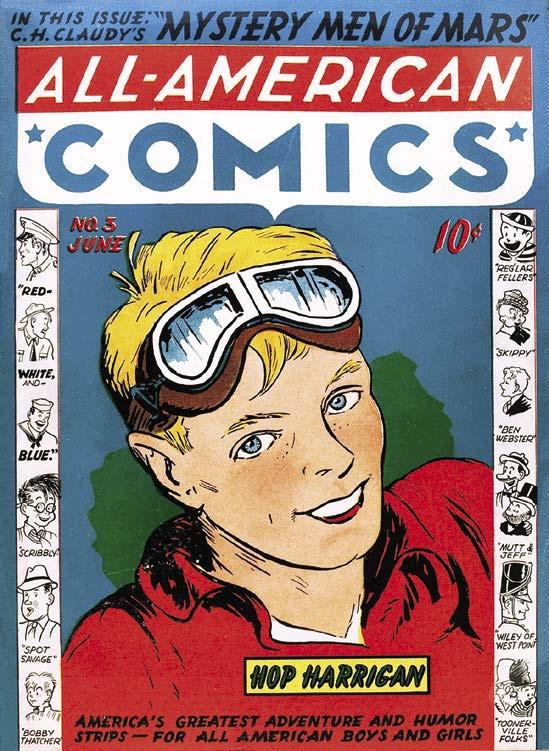

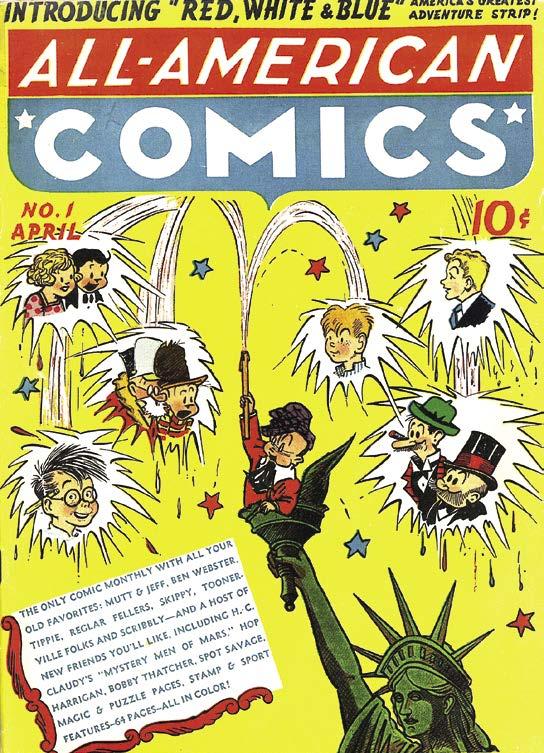

Created by Jon L. Blummer in All-American Comics #1 in April, 1939, Hop Harrigan was one of many young aviator heroes to pop up in the early days of comics. Unlike many of these nascent kid aviators, Hop had a longer life and the honor of apparently being based off of a real flier.

Writer John H. Lienhard, in his book Inventing Modern, believes that Hop’s origin was based off of a popular news item of the time. Adventurous aviators (such as the more wellknown Charles Lindbergh and Amelia Earhart) had been American heroes for the past couple of decades. One such aviator was Douglas “Wrong Way” Corrigan, who supposedly flew across the Atlantic by mistake.

Corrigan, flying a decade-old and second-hand Curtiss-Robin plane he’d bought for $325 and rebuilt himself, went straight from California to New York to file for a transatlantic flight. Skeptical of his old plane, the aviation authorities denied his flight plan.

On July 17, 1938, Corrigan apparently turned 180 degrees and took off over the ocean. He landed in Dublin, Ireland and claimed to not know where he was or how he got there. Corrigan’s license was suspended, even though he claimed his main compass went out and he couldn’t read his backup in the dark. Upon arriving in New York on a ship, his license was reinstated and he was given a huge parade. RKO even cast him as himself in the story of his flight, called The Flying Irishman. Lienhard describes him as “the little guy in his homemade airplane who had beaten the system.”

CHAPTER 7: Hop Harrigan 93

Clear Skies

Hop Harrigan started life as an All-American Boy in a biplane, flirted with superheroics, and then got caught up in the flurry of World War II comic book patriotism.

In his first appearance in All-American Comics #1, Hop Harrigan started in the care of his no-good neighbor, who gained custody of the boy in order to get his inheritance. Hop’s father was a legendary aviator who mysteriously disappeared on a flight, leaving nothing more than his old biplane. When Hop had to decide between the biplane or his adopted father, he pushed the old man out of the way and jumped in the plane, landing at an airfield run by Prop Wash. Saving the life of mechanic Ikky Tinker, Hop landed a job there. With the help of a rich heiress, Gerry (who eventually won him over) they started the All-American Aviation Company. Ikky was later renamed Tank Tinker, a much catchier name that isn’t a direct knock-off of Captain Midnight’s pal Ikky Mudd.

By June’s All-American #3, Hop Harrigan gained the coveted cover boy status but kicked off in five issues with the premieres of sci-fi hero Gary Concord the Ultra-Man, a helmeted muscleman who wore nothing else but a tight-fitting trunks to fight in. Hop had one more cover appearance on #14 and it was all over by #16 .

Writer Bill Finger and artist Marty Nodell’s Green Lantern, drawn by Raymond imitator Shelly Moldoff for the cover, made

his first appearance and stole the cover spot for the next three years. Hop only had one cover appearance in 1943.

The first mention of Hop’s All-American Flying Club showed up in All-American #17 from Aug. 1940, not long after Captain Midnight’s own Secret Squadron radio fan club emerged. It came with a “golden winged emblem,” which had a central wheel with the “Hop Harrigan” name in the center wheel (around the spokes, split between top and bottom, just like the Code-o-graph), and “All-American Flying Club” around the outer ring with eagle wings coming from the sides.

Like Captain Midnight, Hop was on the radio by August 31, 1942. He also stole Cap’s creators, Burt and Moore, who teamed up with Albert Aley to produce the Hop Harrigan radio program that fit into the 5:00 to 6:00 Monday through Friday time slot. The adventures often took place behind German and enemy lines, eschewing the fantastic for more realistic antagonists and situations.

1942 also premiered the Hop Harrigan newspaper strip, by Blummer, a short-lived attempt that only lasted about a year.

Meanwhile, things were changing for National Comics and their companion company All-American. All-American head Charlie Gaines sold his share of his company off to Detective, and the merged imprints were rechristened National Comics. While they would still bear the “DC Comics” logo, they wouldn’t officially adopt DC Comics as their corporate name for a few more decades.

CLIFFHANGER! Cinematic Superheroes of the Serials: 1941–1952

94

(left) Hop’s first appearance was in All-American Comics #1, with one of his few cover appearances (right) two issues later.

Test Flight

Columbia picked up the rights for a Hop Harrigan movie serial, spearheaded by their newest producer: low budget schlockmiester Sam Katzman. Apparently Katzman produced the serials to help offset Columbia’s major box office failures, and did not receive any upfront money from the studio. The half-a-shoestring-budget philosophy would reflect itself in Katzman’s output.

Cahiers du Cinéma summed Katzman and his films as such:

Deserves to be cited as the most prolific of all producers. His films beat all records for speed of shooting, modesty of budget, and artistic nullity.

Katzman was born on the Fourth of July in 1901 in New York and entered the Hollywood film industry by age 13, performing grunt crew gigs like propman and best boy, and ascending the industry ladder a rung at a time.

Sam could have followed the stereotypical American dream and produced the most fantastic motion picture in the history of cinema, but he didn’t: When he gained enough capital in 1935 to strike out with his own Victory Pictures production company, he cranked out films as low dollar as he possibly could. The sets and casts were always on the cheap, employing lesser names like Captain Marvel ’s Tom Tyler, with Katzman even directing some of his own films to save the expense of having to hire someone.

Victory only lasted two years before Katzman went over to Monogram, where he started the East End Kids “kid gang” series of films, and a serving of low budget horror flicks. Katzman’s strength didn’t lie in the quality of his films, but in the profit that could be made from the rushed ultra low-budget production.

“He was a rather unpretentious looking man—he wasn’t small, but he had no chin,” actor Michael Fox said. “I got along splendidly with Sam, although for some reason I think he regarded me as an intellectual. I think anybody who had gone past the sixth grade was an intellectual to Sam.”

Hop Harrigan was during the start of Katzman’s career as Columbia’s premiere movie serial producer. All of his comic book based serials were, with one exception, based off of DC Comics characters.

“I did a picture for Columbia in the early ‘40s, and Katzman was Columbia, and was a great friend of mine. I loved Sam Katzman and his cigars,” actor Johnny Duncan recalled. “He was a very slow-moving and very calm guy. Always sat back in a chair with his mustache smoking his cigar, listening and making his decisions. He was really a wonderful guy, and didn’t want to pay actors nothing. He was cheap that way.”

“He was a nice guy, maybe one of the sweetest in the world,” serial actor Kirk Alyn once recalled. “Once we got past the money stage.”

“We’d always be able to dicker with him on salary,” Alyn added. “Sam would say ‘You know I always take good care of you, kid.’”

“Sam was an absolute genius at making low-budget pictures,” actor and future Lone Ranger star John Hart said. “He never made a real good picture, but he always made money. Sam put a lot of money into Jack Armstrong with a five week schedule where most of his serials were made in three weeks. He had a group of actors who were very loyal to him. He hated drinking— anybody who was a boozer didn’t work for Sam.

CHAPTER 7: Hop Harrigan 95

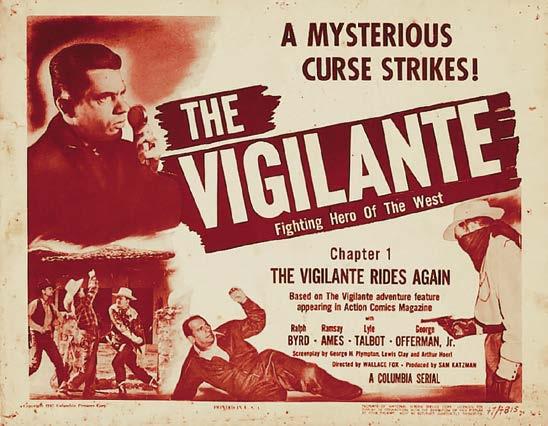

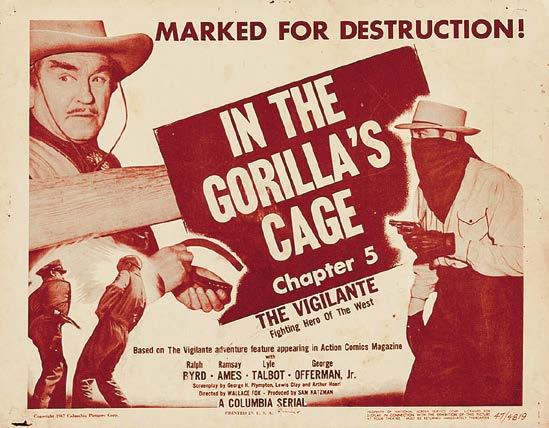

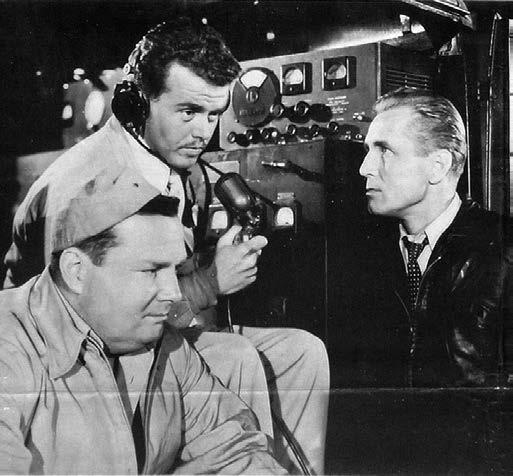

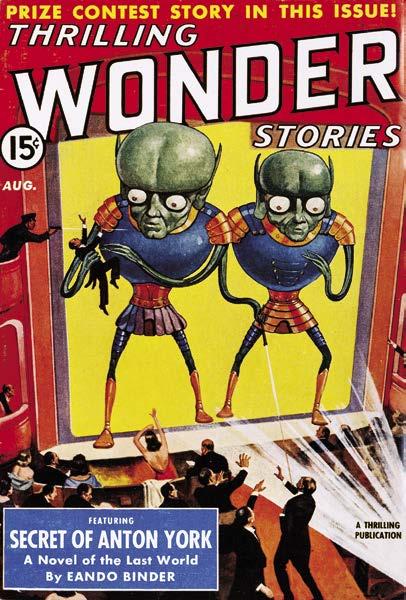

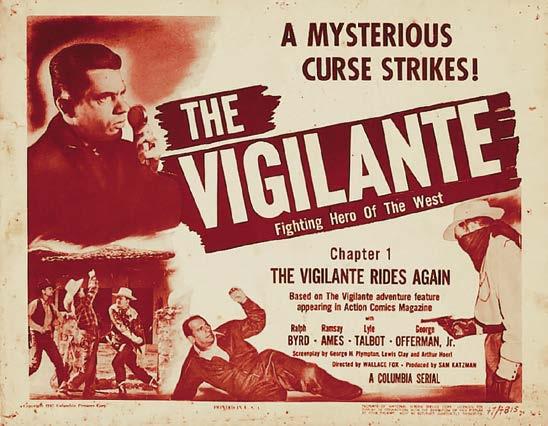

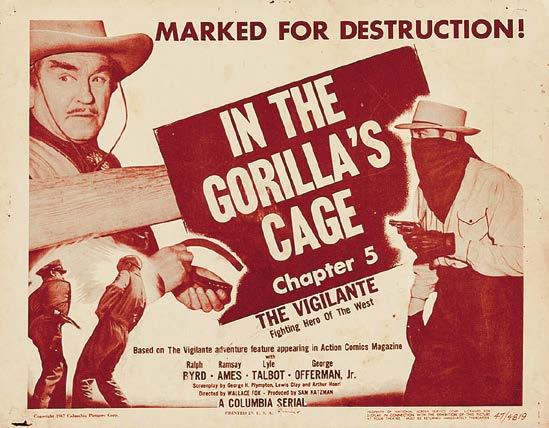

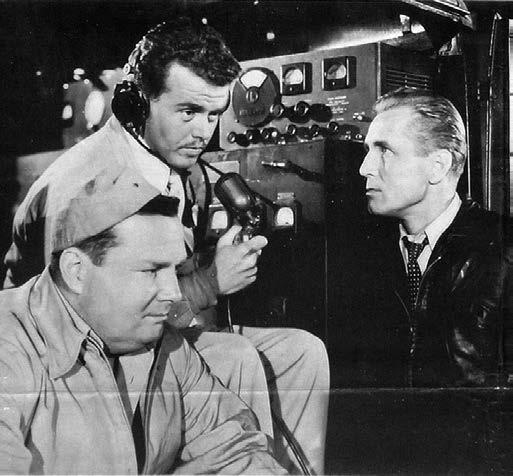

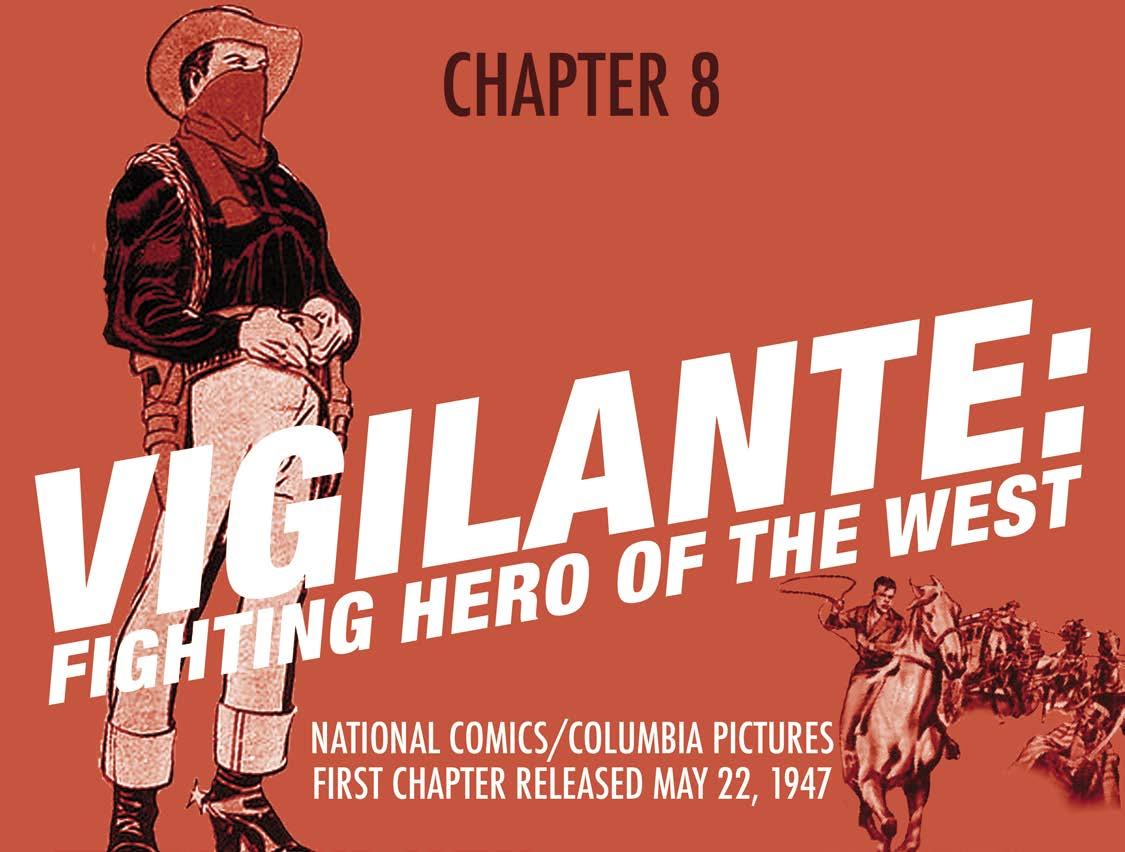

The Vigilante was National’s clever blending of the singing cowboy, the Lone Ranger, and superhero. It’s too bad that Columbia produced the serial, as the character had Republic high-octane movie serial written all over him.

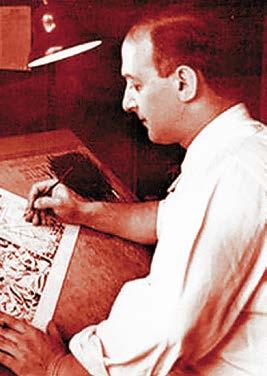

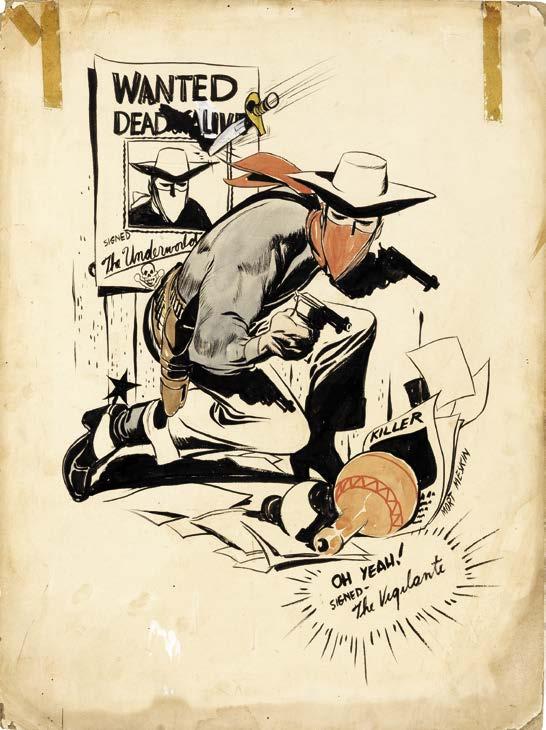

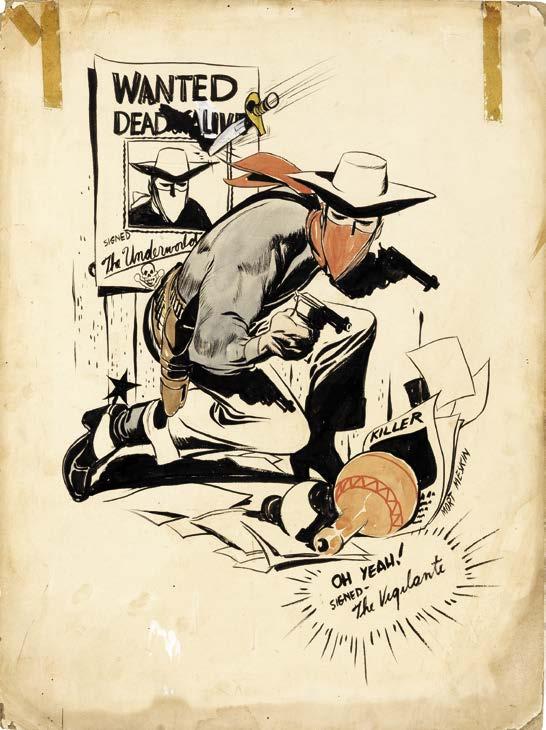

The Vigilante first appeared in Action Comics #42, November, 1941 and was created by writer/ editor Mort Weisinger and artist Mort Meskin. He was Gene Autry-based radio and prairie cowboy, Greg Sanders, who normally acted like a fop, a la Zorro’s everyday identity of Don Diego de la Vega. After Sander’s father was killed by stagecoach bandits, he vowed vengeance on crime as Vigilante, wearing white pants and a blue shirt with a John Wayne-ish flap, and hiding behind a cowboy hat and red bandanna mask.

Meskin designed a powerful, iconic, and eye-catching cowboy, one who passed on a trusty steed and instead stuck with a motorcycle, rushing off with his six guns a-blazin’. In Action Comics #45, Stuff the Chinatown Kid was added to the ranks of politically incorrect comic book sidekicks. They fought their villains, such as the Dummy, a midget who disguised himself as a ventriloquist dummy, in cliffhanger serial-like fashion.

Intended as a mere filler story, Vigilante soon took on a regular slot in Action Comics, with the stories running until 1954’s #198. In 1941, Vigilante became a member of the Seven Soldiers of Victory, a team of other second-string heroes appearing in fourteen issues of Leading Comics

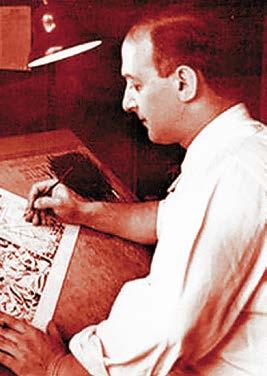

The writer on the original stories was infamous DC Comics editor Mort Weisinger, a frustrated writer who was one of the editorial geniuses of the Golden and Silver Ages of comics. He also

CHAPTER 8: Vigilante 99

Mort Meskin.

happened to leave a trail of wounded creators in his wake.

Weisinger was one of the early comics professionals who came into the medium as a science fiction fan. He was about 13 when he borrowed his first sci-fi pulp magazine from a camp counselor, the issue of Amazing Stories that featured the first Buck Rogers story.

Hooked on the new genre, Mort became part of science fiction fandom, which put him in touch with Julius Schwartz. Ironically, both boys grew up to become two of DC Comics’ most influential editors but, back in 1932, they were merely two awkward adolescents responsible for publishing early science fiction fan magazine, The Time Traveler

That year, Mort also sold his first piece to Amazing Stories, marking his beginning as a pulp writer, which he continued through attending college at NYU for Journalism.