10 minute read

BOOM (eclectic bursts of genius!)

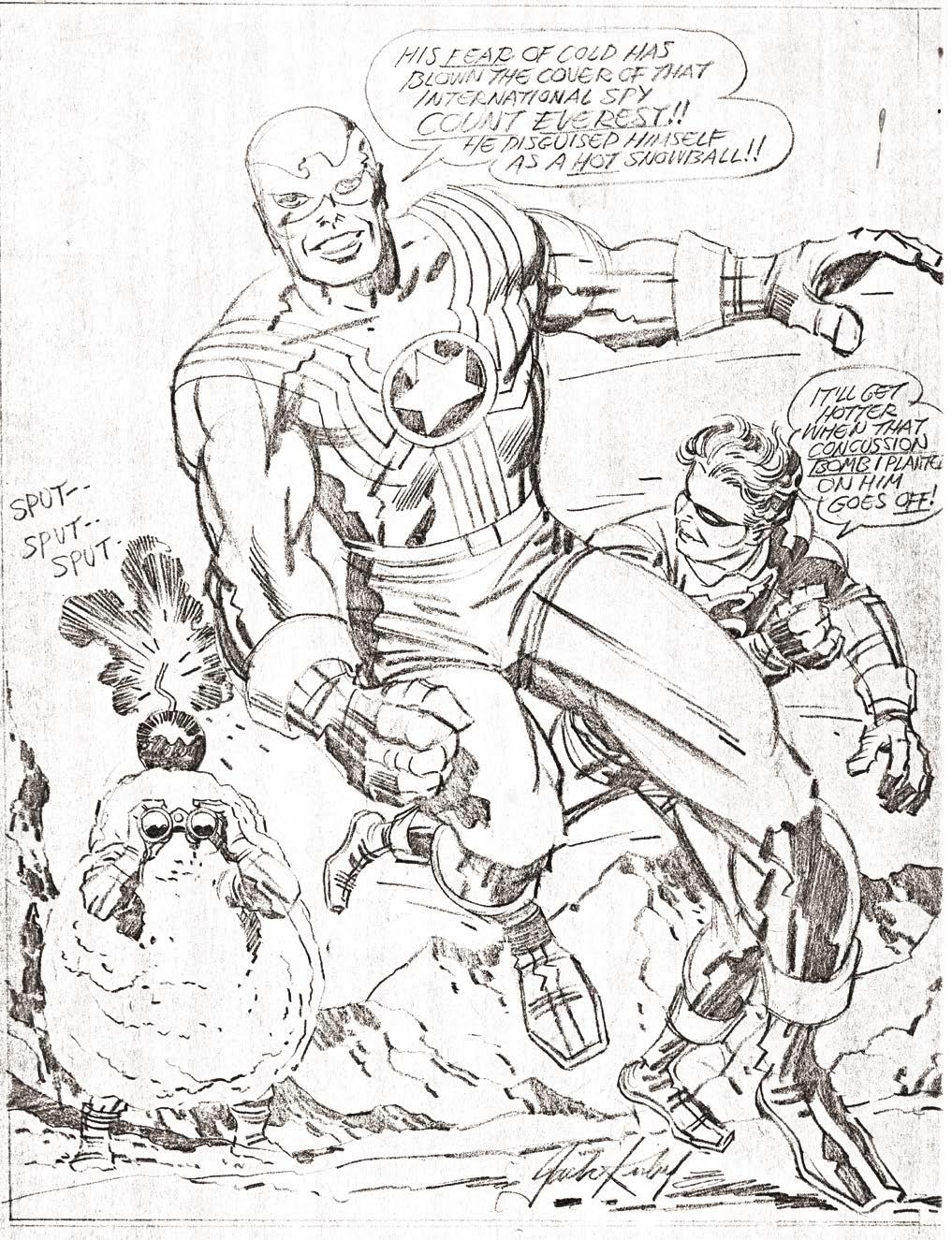

Barry Forshaw is the author of Crime Fiction: A Reader’s Guide and American Noir (available from Amazon) and the editor of Crime Time (www.crimetime. co.uk); he lives in London. CONFRONTING THE RIDICULOUS All readers of this maga- zine will happily accept praise for the comics medium in general, won’t they? After all, why would anyone be looking at The Jack Kirby Collector if they were not a fan of the medium? But here’s something you may not have heard praised before; the possibility that the medium can (that is, for the duration of a story) make the ridiculous—as opposed to the simply imaginative—surprisingly plausible. In comics, somehow, all things are possible—which they are demonstrably not in other fields. Case in point: Jack

Kirby’s work on Fantastic Four—and specifically Mr. Fantastic. The first example of a human being who can stretch and distort his body in astonishing ways was, of course, Jack Cole’s Plastic Man, and Cole was well aware of just how silly (and unscientific) the concept was. Cole played his red-clad hero (and idiotic sidekick Woozy Winks) for laughs—in fact, there are those who would argue that Plastic Man was the greatest humour comic book ever produced. But when Kirby and Stan Lee repurposed the notion with Reed Richards, they largely played it straight, and Kirby enthusiasts were persuaded to willingly accept this most ridiculous of superhero powers. However, there is an earlier example in Kirby’s work of something similar in terms of outrageous notions—but on this earlier occasion, it is perfectly clear that he knew it was impossible to take the concept seriously. In DC’s Tales of the Unexpected #24 (April 1958),

there is a story called “The Two-Dimensional Man” in which the hapless protagonist takes a powder that turns A regular him into a comically-drawn “flat man.” The story is full of column focusing truly bizarre ideas, and Kirby tackles head-on one quite on Kirby’s least absurd sequence in which a group of cows about to be known work, transported are turned into flat, two-dimensional creatures by Barry Forshaw and stacked like a pile of newspapers—even though they are still living and breathing. The hero is next up (accidentally) for the treatment, and the reader has time to wonder why if he has ingested the transformational powder via a cup of tea (he has an English butler—it’s the only way Americans drink tea, of course, when given to them by their London-born butler), how it is possible for his clothes to attain the same two-dimensional status as his body. But the story is great fun, and the best thing in an issue which contains an excellent piece by Lou Cameron, who also provides a rare cover. And “The Two-Dimensional Man” is a reminder of how humour was something else that Kirby could do when necessary. The recent death of Mad magazine’s great caricaturist Mort Drucker makes one wonder about the other things that Kirby might have done in this area, given the chance—although he did do humour work for Marvel and Mad imitators. GARGOYLES Writing a column such as this over a long period— which John Morrow has been kind enough to ask me to do—leads to certain problems. For a start, writers such as myself have to avoid an endless stream of encomiums for the subject of the column (in this case, a certain comics illustrator); that would become a little boring after a while, and—apart from anything else—most readers of The Jack Kirby Collector don’t need to be persuaded of the talents of the man whose name is in the masthead. To that end, over the years, I’ve tried to be frank about what even Kirby’s admirers sometimes admit are the missteps of the Master: such as the fact that his amazingly fertile writing imagination (leaving aside his illustrative skills) was wildly undisciplined—and even in his best work, in need of a stern editorial hand such as that provided by Stan Lee (and which was in less evidence in his last DC period). Having said that, one can instantly start to argue with oneself—despite the purple prose and the occasional incoherent plotting, Kirby’s innovations in those final DCs still produced an amazing bushel of concepts and notions which are still in use today, including one which is central to the current DC universe: the godlike super-villain Darkseid. But back to finding something new to look at in the work of Jack Kirby. Examining a typical issue of Atlas/Marvel’s Strange Tales (#74, from April 1960) will remind the reader of what was becoming a typical package of that era: a lead-off Kirby strip followed by back-ups from the likes of Don Heck and Paul Reinman, topped off with an outing from editor Stan Lee’s other heavy hitter, Steve Ditko. In this issue, the Heck and Reinman tales are unexciting, standard stuff—as they so often are in the books of this period. The Ditko closer, “When the Totem Walks”, is one of his most impressive pieces from this period, with a dynamic splash panel that dispenses with the border and uses the white of the page to great effect. But we’re here to talk about Jack Kirby, and the opening story, “Gorgolla! The Living Gargoyle!!” (overuse of exclamation marks was a Stan Lee

OBSCURA

In 1961, all of America seemed to be monster mad.

The trend had begun on television, with the rise of local “Creature Feature” programs which telecast old monster films. Universal Films were among the most popular. Baby Boomer kids ate them up. This led to Famous Monsters of Filmland magazine, monster gum cards, and misshapen plastic toys. When the Aurora Plastic Company released a Frankenstein model kit late in 1961 (right), demand was so great they could barely keep up with production. At the then-unbranded comic book company Martin Goodman ran, this monster mania did not go unnoticed. The pages of Strange Tales, Tales to Astonish and other fantasy titles were bursting with monsters of all species, the bigger and brawnier the better. When Goodman instructed editor-writer Stan Lee to package a super-hero title, Lee and artist Jack Kirby threw in a brutish monster for good measure. It worked. The Thing became one of the Fantastic Four’s most popular characters.

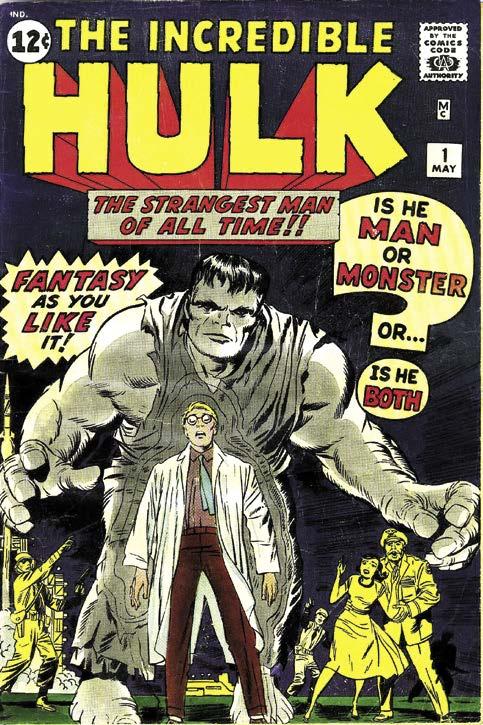

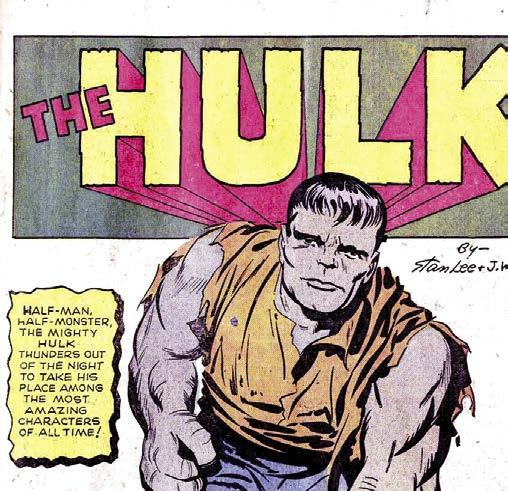

As the year 1962 drew near, the fad showed no signs of abating. Someone at the future Marvel Comics thought that a book built around a continuing monster might sell, and sell big. Whether it was editor Stan Lee, his top artist Jack Kirby, or publisher Martin Goodman is unclear. All three men were central to the creation and execution of The Incredible Hulk, which hit newsstands on March 1, 1962 with a disappointing thud. Three issues later, the Hulk stood on the precipice of cancellation. “Actually, The Hulk was going to be discontinued after the third issue,”

remembered Kirby. “So in formations comes these college guys from Columbia or NYU, and they say, ‘The Hulk is the mascot of our dormitory.’ I knew right away we’d got the college crowd––which we never had before!… I begin to feel, ‘Keep the sunovabitch going!’” The reprieve was brief. The Incredible Hulk was canceled with issue #6 (Kirby left after #5). Reader response to the Fantastic Four’s brutish and brooding Thing seems to have been the initial trigger for the character. “I was trying to think again, ‘What can I do that’s different?’” Lee explained. “I liked the Thing very much, and I thought, ‘What if I get somebody who is a real monster?’ And I remembered in the old movie Frankenstein with Boris Karloff, I had always thought that that monster was the good guy because he didn’t want to hurt anybody, but those idiots with torches were always chasing him up and down the hills…. “So I thought it would be fun to get a monster who is really good but nobody knows it, and they fight him. But then the more I thought about it, I figured it could be dull after awhile just having people chasing a monster. And I remembered Dr. Jekyll and (above) Incredible Mr. Hyde (right).

Hulk #1 (May 1962) I thought, why not treat him like Jekyll and Hyde? He’s contains the cover really a normal man who can’t help turning into a monblurb “Fantasy As You ster. And it would make a very interesting story if, when

Like It!”, mimicking other Marvel monster comics that year, such he needs his monstrous strength the most, the poor guy turns back into a normal man. I could get a lot of story as Tales of Suspense complications.” #25’s declaration, “A Jack Kirby remembered it differently.

Heart-Pounding Tale Of Fantasy!” (below). “The Hulk was my creation,” he claimed. “The Hulk was a prime example of the way I had matured. Here is this guy, Bruce Banner, a scientist, an intellectual who would turn into a primitive monster. The Hulk was my Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. I was borrowing from the classics. The classics are the most powerful stories we have.” Lee and Kirby were children of the Great Depression, the era when

Is He Man or Monster? Marvel’s Mighty… Man-Monster?

Before & After Big and small changes made to Kirby’s work, with commentary by John Morrow

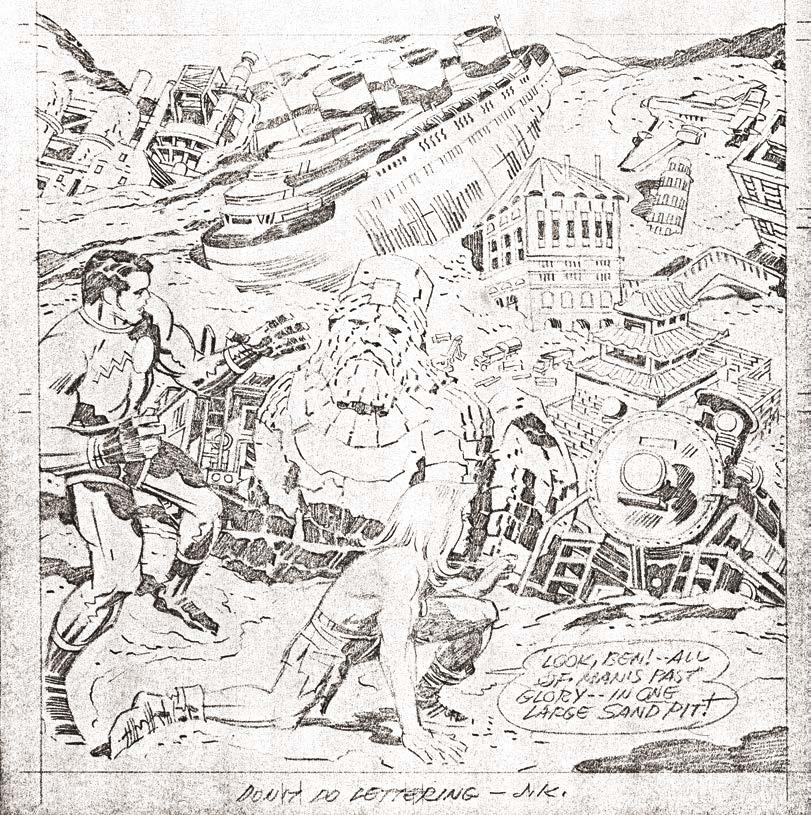

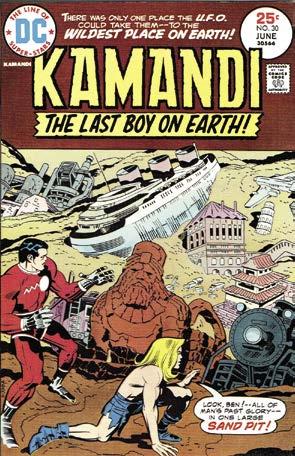

While Kamandi fans don’t meet on an annuRetrospective al basis to bemoan the fact, the consensus is that the tail end of writer/artist/editor Jack Kirby’s run on DC’s Kamandi, The Last Boy on Earth is the weakest stretch of stories during the title’s first three years. Affectionately known as “The U.F.O. Saga,” you simply (below) Pencils for the cover of Kamandi #30, the start of the “U.F.O. can’t compare it to the high quality of the earlier epics involving a young man’s struggle to survive on a post-apocalyptic Earth (caused by the mysterious “Great Disaster”) where animals (lions,

Saga.” Jack’s note tigers, bears, and more) behave as humans, and humans are now

“Don’t do lettering” wild, hunted, herded, and placed in zoos. Kamandi #1-29 contain may’ve been to inker D. Bruce Berry, whose lettering wasn’t at the many of the best adventure stories ever written in comics. On its own terms, however, “The U.F.O. Saga” is still a rousing advensuperior level that Mike ture story that oddly veers off course from its original intentions,

Royer always reached. abruptly shifting to the inevitable “Kamandi in Space” issue, then darting off in a completely different direction, never (right) A very quick marker sketch of Kamandi’s Prince really crossing a finish line so that it can stand completely on its own. On top of that, five chapters into “The U.F.O. Saga,” the official announcement was made that Kirby was leaving DC to explore new challenges (i.e., return to Marvel Comics), and suddenly it was apparent that Kirby (aided and abetted by inker D. Bruce Berry) wasn’t just struggling to

Tuftan, for a fan. control an unwieldy story—he was losing interest entirely and in the process of moving on. This isn’t an in-depth attempt on my part to re-assess or re-evaluate “The U.F.O. Saga.” This is reassurance that the epic remains a terrific read despite the complications and disappointments. The adventure is nearly fifty years old, and I get as big a kick rereading it now as I did while reading it for the first time as a young teen in 1975, and subsequently many times over the last four-plus decades. Honestly, the only flaws I find with “The U.F.O. Saga”? The art is rushed and there’s no conclusion. But as an adventure story, it’s top-notch. It all begins in Kamandi #30 (June 1975), within a beached Unidentified Flying Object where the last boy on Earth and his mutant friend Ben Boxer are taking a nap (see Kamandi #29 for the “super” reason why much needed rest was required). They had stumbled upon the spacecraft during the night and thought it was an abandoned bunker. But the spacecraft’s owner has returned from its wanderings, discovered the infiltrators, and immediately taken action. Kamandi suddenly awakes to find himself and Ben weightless and floating in a compartment of the U.F.O. The alien, encased in a thick

The U.F.O. Saga Kamandi #30-35 reflected on by Jim Kingman